| BALTIC TRIBES Baltic

Tribes :

The Balts were a north-western division of Indo-Europeans. They originated along the Pontic-Caspian steppe prior to the Yamnaya horizon event which saw the widespread outwards migration of Indo-Europeans (IEs). Eventually arriving at the south-eastern shore of Mare Suebicum, the Baltic Sea, around 2500-2000 BC, they spread out to form several later groupings. These can largely be categorised as Lithuanians and most Latvians, plus Couronians, Samogitians, two groups of Galindians, the theorised Dnieper Balts (Eastern Balts), the Pomeranian Balts, the Old Prussians, and the Yotvingians/Sudovians (Western Balts). The Neuri are a more complicated question but are most probably Eastern Balts.

The original spur for this sudden expansion lay in the Near East, somewhere between south-eastern Anatolia (today's Turkey) and northern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where cattle herding was invented when wild aurochs were tamed. This new economy quickly proved its worth and soon spread in all directions in which cattle could graze, along with the people who invented it. Some of them crossed the Caucasian Mountains (the western end on the Black Sea coast would be a favourite location for such a tricky crossing), and spread out amongst the steppe-dwelling proto-Indo-Europeans to the north of the mountains. This cattle herding technology was eventually augmented there by the use of the horse, vital for herding on the vast, open plains of the Pontic-Caspian steppe. The newcomers adopted the local language, and this appears to have formed the basis for centum-speaking Indo-Europeans (involving western Indo-European language groups).

In the forests to the north of this steppeland, relatively untouched groups of forager IEs slowly adapted to the new technology without being subsumed by the newcomers, probably via contact with their steppe-dwelling cousins; these were the satem variety of IE speakers (the later eastern language groups). They were the ancestors of Indo-Iranians, Indo-Aryans, Slavs, and Balts and they also provided part of the ancestry of Germanics (which explains why Germanics were notably different from their Celtic neighbours). Once the horse was introduced, the great steppe nomad expansion soon occurred - known as the Yamnaya horizon - with IEs entering central Europe, Anatolia, the Near East, and Central Asia. Eventually, India, the Iranian highlands, and eastern Asia would follow.

The proto-Balts seem to have been relatively slow to move, or at least they don't seem to have moved too far at first. They preserved archaic forms of Indo-European language, living a secluded life in the forests where they were removed from the major routes of many of the migrations. They and the proto-Slavs were probably indivisible at first, occupying territory along the northern Pontic coast (the Black Sea). Some drift or migration eventually occurred, possibly due in part to the divergent migratory route of the proto-Germanics which may have interrupted their isolation. Even so, the proto-Germanics seem not to have had much to do with them, not culturally or linguistically, at least. This can be proved by the lack of a presence of the cult of Rte in Baltic and Slavic culture. The Germanics themselves may not yet have received their own Rte influence (see the feature link for more details), hence the possibility of some admixture, but nothing that has left a trace in any of the three groups. The cult of Rte was widespread in Indo-Iranians, and the Germanics received a heavy dose of it themselves, but seemingly after their migration, not before, which explains the lack of it amongst the proto-Balts and proto-Slavs. That doesn't explain why these two groups, R1a Y-chromosome satem speakers just like the Indo-Iranians, did not have it anyway. The only reasonable explanation is their isolation in the forests.

Eventually the proto-Balts and the closely-related proto-Slavs divided around 2500 BC, with the former heading towards the Baltic coast. Once there, and pushing the already-present Uralic-speaking Finno-Ugric tribes northwards by their arrival, they spread out westwards along what is now the Polish coast and eastwards as far as the area around Moscow. The Fatyonovo culture is the localised archaeological expression of their settlement here, part of the greater Corded Ware horizon. Late to unite into organised states, they did so in the face of outside pressure (and see the map at the foot of the page for tribal locations).

The Dnieper Balts (or Dniepr) are a theoretical grouping of Eastern Baltic tribes. They are presumed to have occupied territory along the River Dnieper during the Bronze Age (from the mid-second millennium), and were later assimilated by Slavs. The river itself was probably the route followed in the Baltic migration from the Black Sea coast into what is now Belarus and then towards the Baltic coast. The Dnieper Balts are known only through the study of names of bodies of water in this region (hydronyms), with a Baltic influence being discernable from the later Slavic influence or adoption. They have been studied by various experts on the subject which include the renowned archaeologist, Marija Gimbutas, the Lithuanian linguist, Kazimieras Būga, and Russian scientists Vladimir Toporov and O Trubachev, who analysed hydronyms around the higher Dnieper basin. By the 1960s, almost eight hundred hydronyms had been found which could have a Baltic origin.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information by Gediminas Kiveris, Yury Kanavalau, and Leitgiris Living History Club, from The History of the Baltic Countries, Zigmantas Kiaupa, Ain Mäesalu, Ago Pajur, & Gvido Straube (Eds, Estonia 2008), from The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W Anthony, from the Encyclopaedia of Indo-European Culture, J P Mallory & D Q Adams (Eds, 1997), from Mes Baltai (We, the Balts), A Sabaliauskas (Lithuania, 1995), from Encyclopedia Lituanica, Suiedėlis Simas (Ed, Boston, 1970-1978), from Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire Within East-Central Europe, 1295-1345, S C Rowell (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series, Cambridge University Press, 1994), and from External Links: Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Nature.com, and Indo-European Chronology - Countries and Peoples, and Indo-European Etymological Dictionary, J Pokorny, and The Balts, Marija Gimbutas (1963, previously available online thanks to Gabriella at Vaidilute, but still available as a PDF - click or tap on link to download or access it), and Leitgiris.)

c.3000 BC :

A date of around 3000 BC is generally used as the probable point at which Indo-Europeans begin to separate into definite proto languages which are not intelligible to each other. A western group will evolve into Celtic, Italic, and other possible minor branches, while a proto-Germanic branch heads towards the north-west and the Baltic coastline. Perhaps initially part of the same movement, or a second wave of movement, the proto-Balts and proto-Slavs form a 'North Indo-European' group which largely remains in what is now Ukraine and south-western Russia.

An eastern branch - or perhaps a branch that stays in the steppe homeland for another millennium or so and which therefore becomes an eastern branch by default because the rest have headed off west - apparently calling themselves Arya or something similar eventually form the ancestors of much of India's modern population, plus the various branches of Indo-Iranians.

By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe

c.2500 BC :

The Corded Ware culture (or Boat Axe culture) arrives in southern Finland, along the coastal regions, as well as in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, western Russia, Poland, northern Germany, Denmark, and southern Sweden. These new, probably early Indo-European, arrivals also have some domesticated animals and bring agriculture with them, although they continue to exist alongside universally-practised hunter-gather activities for some time. Both of these groups - foragers and farmers - form the proto-Baltic ancestors of the later Latvians and Lithuanians, plus various other groups which are later subsumed or extinguished.

The Corded Ware culture is essentially a westwards expression of the Yamnaya horizon of the Pontic-Caspian steppe. In central Europe it replaces the earlier Lengyel culture. However, the concept of Corded Ware isn't as simple as a straightforward replacement of one culture by another. In fact, this physical culture appears to span numerous different ethnicities, not just Indo-Europeans. Perhaps called it a melting pot culture wouldn't be far from the truth.

c.2350 BC :

Corded Ware culture gradually gives way to the Bell Beaker horizon. This had started out in Iberia and had spread to central Europe where it has been picked up with enthusiasm by West Indo-Europeans who turn it into a true culture rather than the cultural influence of an horizon. Elements of Bell Beaker reach the Balts, but how influential they are is unclear. Cultures of the eastern Baltic region between this time and the beginning of the Bronze Age around the middle of the second millennium BC remain relatively obscure.

1700s BC :

Around this time the copper industry in the western Carpathian and eastern Alpine zone makes remarkable progress, but the metal products of central Europe are not immediately transmitted to the Baltic area. In metallurgy, it remains peripheral, undoubtedly because the entire region between the Baltic Sea and Russia is lacking any local sources of copper. The development of a Baltic metal culture depends entirely upon imports from central Europe to the Baltic Sea area and from the Caucasian and southern Ural metallurgical centres to central Russia.

c.1600 BC :

By now the people of the central European Unetice culture have established commercial relations with the Mycenaeans. A transcontinental amber trade has already begun at about the same time as the Baltic Bronze Age, and amber has already been in some demand by the Uneticians themselves. Now, though, the amber trade reaches an amazing volume. The Uneticians import their amber from the Balts and from the Germanic peoples in Jutland, and it is estimated that at least eighty per cent of the graves of classical Unetice contain amber beads.

The Unetice daggers shown here are typical of the later stages of this culture, by which time it was an enthusiastic member of the European amber trade with the Balts and Germanics of the north c.1400 BC :

The Western Balts of the Bronze Age seem to cover the whole of Pomerania to the lower Oder, and what is now eastern Poland to the Bug and upper Pripet basins in the south. Archaeology later shows that the same culture can be found here as the one that is widespread in ancient Prussian lands. The southern extent of the Prussians along the River Bug, a tributary of the Vistula, is indicated by the Prussian river names. Towards its end the neighbouring Unetice culture grows progressively in wealth and power, until its influence reaches all of continental Europe. Around 1400 BC it expands into the Middle Danube basin and Transylvania, and its military power controls a great part of the European continent. Baltic borders are pushed inwards somewhat at this expansion, but not to any dramatic extent.

The proto-Baltic sphere itself becomes divided into several zones of influence during the Bronze Age. The western zone, covering eastern Poland, eastern Prussia, and western parts of Lithuania and Latvia, is under the influence of the central European metallurgical centre. Throughout the Bronze Age its culture progresses with the same rhythm as in central Europe. In the eastern or continental zone, amid the forests which extend from eastern Lithuania and Latvia to the upper Volga basin, the people retain an archaic character, with some influence from their Slav neighbours in southern Russia. This division continues throughout the remaining prehistoric period: the western Balts, ancestors of the Prussians and Couronians of history, are culturally similar to the people of central Europe, to the culture created by Illyrians and Celts, and to their western neighbours, the Germanic peoples. The eastern Balts are in active contact with the Finno-Ugrics, Cimmerians, proto-Scythians, and early Slavs.

c.1300 BC :

The appearance and rapid expansion of the central European Lusatian culture around this time seems to do more than its predecessor when it comes to squeezing the territory of the Baltic tribes. It very quickly takes over the entire south-western corner of Baltic dominance - central, eastern, and southern Poland, areas that the Balts never regain.

The Uralic-speaking Finno-Ugrics living in the neighbourhood of the Balts become to a certain degree Indo-Europeanised. Over the course of several millennia, particularly during the Early Iron Age and the first centuries AD, Finno-Ugric culture in the upper Volga basin and north of the River Daugava-Dvina becomes adapted to food production, and even the habitat pattern - arranging villages on hills and the building of rectangular houses - is borrowed from the Balts.

c.1200s BC :

A large proportion of the early Slavs in the Middle Dnieper basin fall under the rule of the Scythians, but the Finno-Ugric tribes and the eastern Balts living in the forested areas remain outside the orbit of strong Scythian influence.

The appearance of ferocious mounted Scythian warriors in the lands to the south of the Balts must have instilled a sense of worry and fear in many groups, but the Balts always managed to remain independent of their control (although armour such as that pictured here certainly did not appear so early), while above is a map showing the Scythian lands at their greatest extent 1100s BC :

Iron appears in central Europe, but not until the eighth century does it revolutionise men's lives and only then does it reach northern Europe. Even then iron is still extremely rare in the Baltic area (until the sixth century BC), and the general cultural level continues to have an almost pure Bronze Age character. The dividing line at about the end of the eighth century BC signifies a change in culture due not so much to technological innovations as to new historical events - the Scythians suddenly expand out of the Pontic steppe region.

The Bronze Age is still a rather obscure period in the area between eastern Lithuania and Latvia and the Oka river basin in central Russia. From pottery remains in fortified hill top villages it can be seen that, during the end of the second millennium BC and the beginning of the first, a cultural differentiation gradually takes place, and before the beginning of the Early Iron Age several local groups have formed. One is known as the Brushed Pottery group of eastern Lithuania, southern Latvia, and north-western Belarus (known in Lithuania as the Kernavė group). Another, which is closely related to the Brushed Pottery, is the Milograd group in southern Belarus and the northern fringes of western Ukraine. A third is known as the Plain Pottery group which occupies the Desna, upper Dnieper, upper Oka, and upper Don basins in central Russia. The last of those, in the basins of the Desna and upper Don, is known more specifically as the Bondarikha for the Late Bronze Age centuries and Jukhnovo for the Early Iron Age and the first centuries AD.

c.800 - 600 BC :

This is the period of Scythian expansion from the Black Sea area into central Europe. These steppe horsemen who appear in Moravia (now eastern Czechia), and what is now Romania and Hungary must be early Scythians, the successors of the south Russian Srubna culture of the Bronze Age which itself had constantly been pushing towards the west. They introduce eastern types of horse gear, oriental animal art, timber graves, and inhumation rites. Before entering Central Europe, they conquer the Cimmerians on the northern shores of the Black Sea and in the northern Caucasus, driving them out and dominating the northern Black Sea region.

There they acquire much of the Caucasian and Cimmerian cultural legacy and mix them with their own Ponto-Caucasian cultural elements. These oriental influences appreciably change the material culture of central Europe. The Baltic and Germanic cultures in northern Europe remain untouched by the Scythian incursions, but the new cultural elements reached them through continuous commercial relations with central Europe.

c.600 - 500 BC :

The Lusatian culture still persists in the first centuries of the Early Iron Age. The amber trade is not cut off and the Lusatians continue to be mediators between the Baltic and Germanic amber gatherers and the Hallstatt culture in the eastern Alpine area and, beginning in the seventh century, the Etruscans in Italy. Novelties such as bronze horse-gear comprising bridle-bits, cheek-pieces and ornamental plates, as well as the initial iron objects, are transmitted into the Baltic area by the Lusatians.

Again, as during the Bronze Age, hoards and the most richly furnished graves are concentrated in the source area of amber: on the Samland peninsula and on both sides of the lower Vistula. Under great pressure due to Scythian raids, the Lusatian eventually gives way to the Pomeranian Face-Urn culture. The Western Balts of this period are sometimes labelled a cairns culture, although they share elements of the Face-Urn culture too, perhaps even being a driving force in its southwards expansion.

Cremation urns of the Kashubian Group, part of the Lusatian culture, which was the predominant method of disposing of the dead during the entire culture period The Scythians reach the southern borders of the western Baltic lands, but apparently do not succeed in penetrating farther north. Only a few arrowheads of Scythian type have been found in East Prussia and southern Lithuania. A chain of western Baltic strongholds in northern Poland and in the southern part of East Prussia arise which very probably are built for resisting the southern invaders. The Scythian high tide lasts only until the end of the fifth century BC. After that they no longer appear in the north, and possibly it is Baltic resistance which helps to end the Scythian threat.

513 - 512 BC :

As the centuries have gone by, the Scythians have become involved in wars against the invading Persians. Thanks to this the northern tribes are also disturbed. Herodotus describes these wars in Book IV of his history, these being the earliest surviving written records concerning the history of Eastern Europe at the end of the sixth century BC. Herodotus mentions and approximately locates the seats of the Androphagi, Budini, Melanchlaeni, Neuri, and other tribes living to the north of Scythia.

c.400 BC :

The Celts of the La Tène culture arrive in Bohemia and southern Poland, the northern limit of Celtic expansion, although there remains the question of where the Belgae and Venedi are located. This La Tène expansion is led by the Boii tribe which makes Bohemia its home for the next three centuries, but the same expansion also stops the Pomeranian Face-Urn culture from expanding any further south. Western and southern Poland have also been disrupted by Scythian raids, but these suddenly drop off around 400 BC, leaving the Face-Urn culture free to expand instead across the entire Vistula basin and to reach the upper Dniester in Ukraine, thereby bypassing the La Tène Celts.

2nd century BC :

The changeless life of the eastern Baltic tribes in the Dnieper basin is disturbed by the appearance of the Zarubintsy, assumed to be Slavs (the name originates in Zarubinec cemetery to the south of Kiev on the River Dnieper, excavated in 1899). The Zarubintsy invade the lands of the the Milograd people along the River Pripet, up the Dnieper and its tributaries, and in the southern territories which are inhabited by the people of the Plain Pottery culture.

A peasant folk on a cultural level which is similar to that of the eastern Balts, Zarubintsy archaeological remains contrast in every detail with those of the older population. Their intrusion must be interpreted as the first Slavic expansion northwards from the lands lying in the immediate neighbourhood. Their movements may have been prompted by the early expansion of the western Baltic tribe which is a carrier of the Face-Urn culture and the subsequent Celtic expansion into Eastern Europe.

A Pomeranian/Face-Urn culture tomb chest constructed at a time of greater metallurgy skills but with weaker ceramic skills when compared to the previous Lusatian culture c.AD 50 - 150 :

The arrival on the southern Baltic coastline of the Gothic people in the first and second centuries AD has a great impact on the Baltic population there. The strongest tribe of the western Baltic bloc which had previously manifested itself in face and pot-covered urn graves of the Face-Urn culture eventually disintegrates due to this and the preceding Celtic expansion. The other Baltic tribes have been less touched by outside influences and have conservatively preserved their local character.

It is generally thought that the Gothic arrival now results in the western Balts retreating towards eastern Lithuania, but perhaps the previously mentioned tribal disintegration is the true reason for the disappearance of Baltic culture along the coast at this time. It is also apparent from Celtic influence on the early Goths (in the form of the first king's name, at least) that the 'Eastern Celts' in the form of the Venedi already control the mouth of the Vistula. In all probability though, due to the ethnic affinity of these peoples, peaceful relations are still established. The appearance of various new groups of pottery, part of the Oxhöft and Willenberg cultures, testifies to the further merging of these ethnic groupings.

The ancestors of the Galindians, Lets, Lithuanians, Natangians, Sambians, and Semigallians continue throughout the entire Early Iron Age to build stone cists in which they place urns of a family or kin, covering them with an earth barrow secured by a stone pavement from above and stone rings around. While available, Middle and Late La Tène fibulae are also imported and imitated. In marked contrast to Celtic and Germanic graves, however, weapons are extremely rare in Baltic graves. The inland Prussian tribes seem to live a rather peaceful life.

Other Baltic tribes are now developing their own distinctive burial rites. Sudovians build stone barrows, Couronians place their dead in stone circles or rectangular walls, while their neighbours in central Lithuania use flat graves supporting tree-trunk coffins with stones. The differentiation of local burial rites from around this time permits modern scholars the chance of perceiving tribal borders between the various Baltic tribes, which thereafter remain unchanged in this region until the coming of the Germans. Until then, there is no evidence of migrations, shifts of population, or invasions of the Baltic lands by foreign peoples.

The mouth of the Vistula in the first century AD was an ideal route for settlement for groups coming south from Scandinavia, but also for groups migrating along the coast such as the speculated movement of Venedi Celts, while above is a map showing the locations of European tribes around the first centuries BC and AD c.150 :

Ptolemy, who writes in the mid-second century, records the existence of the Galindai and Soudinoi tribes, the later Galindians and Sudovians (the latter also known as Yotvingians). Both of these are Western Balts, but not Old Prussians, although they do closely border the Old Prussians to the south. The fact that these names already exist shows that Prussian tribes (and probably the other Baltic tribes) have their own names and that they survive virtually unchanged for the next millennium.

c.150 - 200 :

Far from remaining settled where they are in Poland, the Goths gradually renew their migration, now moving slowly southwards from the Oder and Vistula, heading on a path that will eventually take them into Ukraine. The migration could be caused by pressure from the Baltic tribes, early segments of the later Old Prussians and Lithuanians who are expanding back into territory they had lost to the Germanic tribes in the first century AD. The Prussians hold onto their newly-regained territory for the next millennium or so.

100s - 400s :

Between the second and fifth centuries AD the material standards of the Baltic culture rise tremendously, due to intensive amber trade with the provinces of the Roman empire. The eastern Baltic area becomes a strong cultural centre, and its influences extended across north-eastern Europe. This is the Baltic culture's 'golden age', according to Marija Gimbutas.

Archaeological finds demonstrate how for centuries bronze and iron tools and ornaments are exported from the Balts to Uralic-speaking Finno-Ugrian lands. The western Finnic, Mari, and Mordvin areas are flooded with or strongly influenced by ornaments that are typical of the Baltic culture. Where the long history of Baltic-Finno-Ugric relations is concerned, language and archaeological sources go hand-in-hand, and Baltic loan words into Volga-Finnic languages pay witness to this.

The Baltic golden age begins to fade from around the end of the fourth century or in the early part of the fifth century, as eastern Slav expansion reaches the Baltic lands in what is now western Russia. The gradual influx of Slavs continues into the twelfth century and beyond.

5th century :

In the first half of the fifth century, there is some evidence of a new wave of invaders in Lithuania. There is every reason to believe that nomadic hordes (either the Huns or a fringe group related to or vassals of them) carry out raids on the forts of southern and eastern Lithuania. Traces of fires and three blade spearheads are later uncovered at the forts of Aukstadvaris, Kernave, Pasvonis, and Vilnius to support the idea. An increase in fortifications around hill forts and their associated villages, with the use of timber constructions and tamped clay for building ramparts, can be observed from the fifth century onwards, probably as a reaction to these raids and also to Slavic pressure (probably one and the same thing).

The approach of the Huns into central Europe spread terror and fear, and not without good reason as their unfamiliar battle tactics defeated opponent after opponent Although Prussian tribes have returned westwards to reoccupy some of the lands previously lost to East Germanic tribes, they start to come under pressure from Slavs who are now migrating into central Poland towards the later part of the same century, in regions such as Galicia, Lusatia, and Silesia. This migration is a product of the Hunnic invasion of their traditional lands. Masuria is also reoccupied, by the West Baltic tribe of the Galindians, after parts of it have been abandoned by the Vidivarii and their preceding Willenberg culture ancestors.

To the east, however, it is still largely a case of Balts integrating with Finno-Ugric tribes. Many barrows in these areas yield purely Baltic finds of the Let type. These date from the fifth to twelfth centuries AD. Even to the south of Smolensk, Moscow, and Kaluga, along the tributaries of the River Zhizdra and upper Desna, a number of excavated barrow cemeteries and hill forts of the Baltic type yield finds which are related or identical to those in eastern Latvia, and which can be dated up to the twelfth century. The archaeological finds also fully confirm a dating up to the twelfth century for the remnants of those Balts who live to the west of Moscow, in the area between Smolensk, Kaluga and Brjansk, the Galindians.

7th century :

The Baltic tribes enjoy what could be termed a 'second golden age', buoyed by rapidly-expanding Viking trade networks which are reaching far to the west and deep into Eastern Europe to establish contacts with the Byzantine empire at Constantinople. It's not all peaceful trade, however. The Vikings see the Balts as a viable target for raids, little realising at first how good are the Balts at defending their territories and even striking back at Viking targets. To the south the Slavs also pose a threat, but the well-equipped cavalry of the southern Baltic tribes, especially it must be assumed the Galindians and Yotvingians, serves to prevent the Slavs from penetrating into Baltic lands.

The numerous Baltic tribes are currently ruled by powerful chieftains and landlords, a system which remains in place until the beginning of recorded history in the region. Among the Baltic tribes the Prussians and Couronians continue to play leading roles. In the previous century or so, the Lets have expanded their territory to cover much of northern Latvia, replacing the previously dominant Finno-Ugric tribes there, the early Estonians.

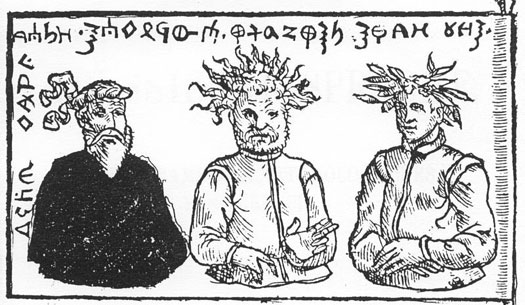

The gods of the Old Prussians were Patrimps, Parkuns, and Patolls (sounding like modern Latvian names in the near-compulsory 's' at the end of each name) who were related to the principle cycles of human life - birth and growth, maturity, and ageing and death, while above is a map covering the creation of the Rus principalities in AD 862 and 882 8th century :

By this century, small Slavic states are beginning to emerge in the region of Poland, and these expand and coalesce over the course of the next century. Western Balts also still occupy regions of Poland, mostly around the lower Vistula. Two tribes named by Ptolemy in the mid-second century, the Galindai and Soudinoi, survive as the Galindians (in Masuria and the northern fringes of Mazovia) and the Sudovians/Yotvingians into the eleventh century, before being absorbed into the duchy of Poland. These Western Balts are survived by their kinfolk, the Old Prussians, although remaining groups of independent Western Galindians do eventually become classed as Old Prussians themselves.

9th century :

From the beginning of the Slavic expansion to the formation of the three Slavic states, Novgorod, Ryazan, and Kiev, in the ninth century and even several centuries later, there are considerable numbers of Balts in what is now Belarus and in the west of greater Russia. The process of Slavicisation which had begun in prehistoric times continues into the nineteenth century. Belarussians borrow many words, most of them in daily usage, from the Lithuanian peasant vocabulary. The ethnography in the districts of Kaluga, Moscow, Smolensk, Vitebsk, Polotsk, and Minsk to the middle of the nineteenth century is highly indicative of the Baltic character. Indeed, Slavicised eastern Balts make up much of the population of modern Belarus and part of greater Russia.

997 :

St Adalbert of Prague, sent by the Pope into Prussian lands to convert the pagans, is escorted by soldiers granted to him by Boleslaw I the Brave, duke of Poland. The twelfth century bronze door of the cathedral in Gniezno in northern Poland depicts scenes of Adalbert's Prussians, showing them with spears, swords, and shields. They are beardless but with moustaches, have trimmed hair, and are wearing kilts, blouses, and bracelets. Adalbert refuses to heed warnings to stay away from the sacred oak trees (it is customary for sacred oaks to be cut down by missionaries to show that Christianity is stronger than any spirits they are supposed to contain). Instead, Adalbert is executed for sacrilege. Boleslaw begins a series of unsuccessful attempts at conquering the Prussians.

1009 :

The annals of the town of Quedlinburg in Germany report the arrival of Saint Brunon, known more normally as Bonifatius, on missionary work among the Prussians. His attempt ends in failure, and it is believed he is killed together with his eighteen companions somewhere in the vicinity of the Lithuanian border (the first mention of 'Lithuania' in written sources).

By around AD 1000 the south-eastern Baltic coast contained a host of known tribes which can be collected into three major groups - Prussians, Latvians, and Lithuanians 1180 :

German Christian missionaries arrive, converting small numbers of Balts and probably establishing nascent congregations. On the whole the Balts appear reluctant to convert, perhaps fervently so, which means that German Crusaders are sent to the Lats and their neighbouring tribes to convert the pagan population - a pretext for a grab for land and resources which is supported by the Pope. They are strongly opposed, although extremely little is known about the Liv native leaders who lead that opposition.

In the east, the Eastern Galindians have already been recorded by Russian chroniclers as the Goliadj (in 1058), and have been the target of a Rus campaign (in 1147). There appear to be no further mentions of them by the Rus but their eventual absorption into later Russian society probably takes several more centuries.

1236 - 1241 :

The Order of the Knights are decimated by the Samogitians and Semigallians at the Battle of Schaulen (Saule). The defeat allows the Lithuanians to consolidate their territories and form a single state which will stand against the invaders in the future. The following year, what remains of the Order joins the Teutonic Knights as an autonomous branch in Livonia, now known as the Livonian Order, or Livonian Knights. While being subject to the grand master of the Teutonic Knights, the Livonian Knights continue to operate on their own behalf.

The Teutonic Knights pursue their own goals in Prussia. By 1237-1238, Pamedė (of the Pomesanians) and Pagudė (of the Pogesanians) are already under the Order's rule. Next, the Teutons push on along the Frisches Haff and in 1240 defeat the united Bard (Bartians), Natangians, and Warmians. In 1241 the conquered and newly-baptised Prussians, no longer able to stand the oppression of the conquerors, rise up in revolt, but they are defeated by 1249. Following this interruption, the Order continues its advance to the north, intent on forming its own military-religious state (known as the Ordenstaat) which it governs for the next three hundred years.

1250s - 1280s? :

The Yotvingians lead the raid on the Teutonic Knight stronghold of Chełmno in 1263, during the Great Prussian Uprising (1260-1274). Later, with Lithuanian support, they form a principle part of four thousand men who fight against the Teutonic Knights, but in the end they are defeated and subjugated.

At the same time, in 1283, the Knights continue to advance north. Having already conquered the lands of the Skalvs and part of that of the Yotvingians, they now drive the Nadruvians to the River Nemunas, right on the border with Lithuania. The population of these areas is killed off, with only a few managing to escape across the border.

By about AD 1000 the final locations of the Baltic tribes were well known by the Germans who were beginning their attempts to subdue and control them, although the work would take a few centuries to complete and the Lithuanians would never be conquered by them In fact, although the arrival of the Germans had started off as a trickle, it had soon became a flood in the twelfth century. This marks the gradual end of Baltic tribal existence and the start of larger states which are created by the Germans themselves (in Livonia and Prussia). The Lithuanians manage to forge an independent state of their own which survives to this day, and they are joined in that independence in 1918 by the Latvian state. Kaliningrad marks the remnants of Old Prussia.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |