| BABAK KHORRAMDIN The

Man :

Babak's Early Life :

Babak's Introduction to Khurramdin :

Javidan taught Babak the principles of the Khurramdin and at some point Babak appears to have adopted the name Babak Khorramdin.

Babak's Decision to Revolt :

Babak's Revolt Against the Arabs :

His army consisted of farmers who had shunned the taking of life and whose only weapons training was sling-shots. Nevertheless, Babak moulded them into a fighting force that took on the well trained and battle hardened Arabs. Soon people in Hamadan, Isfahan and Iraq were joining Babak's group of followers.

From 817 to 837, Babak's force fought hard. His insurrection developed into the most serious revolt the Arabs had faced since their invasion of the Aryan lands. Gardizi reports that Mazyar (d. 839 CE), the ispahbad (sepabad) of Mazandaran and Gorgan (Tabaristan), who had abandoned Zoroastrianism for Islam, decided to become a Khurramdin after learning of Babak's campaign and successes.

In

819-820, The Arab caliphate sent Yahya ibn Mu'adh to battle Babak,

but Babak could not be defeated. Two years came armies under Isa

ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Khalid and these too very defeated.

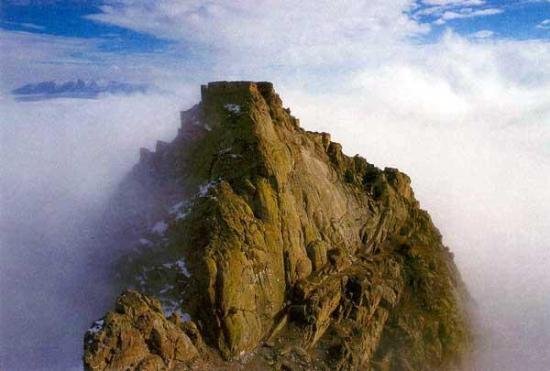

Babak's Castle. Ghaleye Babak :

Babak's Castle exists today as ruins on a mountain top and, it is known variously. It is known as Badd, Ghaley-e / Qale-e Babak and Qala-e Jomhur. In Turkish Azeri, it is also known as Bazz Galasi.

The castle itself was not built by Babak. Its origins goes back to the Sassanian era (c 249-650 CE) and possible even the Parthian era (c 227 BCE - 249 CE).

Today, Babak has become a national hero and the castle's ruins have become a Iranian nationalist symbol and the castle is also known as the Castle of the Republic or the Immortal Castle. Every July 10th, many Iranians journey to the castle to celebrate the life and ideals of Babak and his companions. Their sacrifice in the giving of their lives while seeking to free Iran from Arab domination as well as their efforts for the preservation of Iranian culture are also honoured.

The citadel's ruins are located in East Azarbaijan Province some 50 km north Ahar city some 5 km southwest of Kalibar town as the crow flies. It overlooks the left bank of a tributary of the river Qarasu. The surrounding mountains are called the Jomhur mountains and the mountains are home to the Arasbaran or (in Turkish, Qaradag) forest, a UNESCO registered biosphere.

The structure was built on a mountain-top 2,300-2,600 m above sea level, and is surrounded on all sides by ravines 400-600 m deep.

Access to the castle is a narrow track that winds its way across patches of dense forest, through gorges, and up steep slopes. The final approach to the castle's gate is through a narrow defile wide enough for only one person to walk at a time. Large military equipment can be carried up this path. The citadel itself was located a further 100 m climb from the castle's walls via a narrow path along a ridge, and the path once again was wide enough for only one person. The ridge is surrounded by a forested ravine some 100 m deep.

Babak had other castles as well (Nafisi, pp. 69-71; Tabatabai, pp. 472-75).

Babak's Defeat & Execution :

Babak asked Afshin if he could spend a last night at his castle at Badhdh and Afshin consented. That castle would come to be known as Ghaleye Babak. Haydar Afshin delivered Babak as a prisioner to the Abbasid Caliph who with characteristic Arab cruelty had his executioners first cut off his legs and then his hands. Legend has it that as a final act of defiance, Babak rinsed his face with the blood that poured from his severed limbs before succumbing to his wounds.

A year after Babak's execution in 838 CE, Mazyar of Mazandaran was captured and killed. A similar fate awaited Afshin, whose sincere adherence to Islam and allegiance to the caliphate was questioned.

After the defeat of the Khurramdins, there is no longer any mention of non-Muslim uprisings in Iran. Even references to Zoroastrians in Muslim documents become rare.

Babak & Khurramdin's Humane Reputation :

Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi who was a mortal enemy of Babak states that Babak and his followers, most of whom were Zoroastrians, practiced great religious tolerance and (despite the harm that Muslims had caused Zoroastrians) allowed Muslims to freely practice their religion and even helped them build a mosque. Abu Mansur mentions that the Khurrami were of the Mazdakite school. When we put the Baghdadi and Mansur statements together, we have that Babak and his Khurrami followers were of the Mazdaki school (denomination) in Zoroastrianism.

Mazdakite influence seems evident in the social order he and his followers were trying a build - a classless society where rich landowners and military lords did not oppress the common person. He divested landowners of land they had obtained through illegal means and distributed the land free to farmers.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |