| VEHRKANA Ninth

Vendidad-Avestan Nation :

During Achaemenian times (c. 650-330 BCE), the kingdom was often grouped together with Parthava (Parthia) for administrative and tax collection purposes. The two kingdoms also often acted in concert and we first hear of this tandem groping when they rebelled against Darius the Great's ascension to the throne of the Persian empire. The revolt was suppressed by Darius in 521 BCE.

The Region & Features :

Golestan Province is bounded by the province of Mazandaran and the Caspian Sea to the west, the Republic of Turkmenistan to the north, the province of North Khorasan (Shomali) to the east, and the Alborz mountain range and the province of Semnan to the south.

Until 1997, Golestan was a part of Mazandaran province. In the census of that year, 294 persons declared themselves as Zoroastrian, 77% of whom lived in rural areas.

Even in ancient times, Gorgan / Verkana was noted for its beauty. Strabo (c 63/64 BCE - 24 CE) states in 11.7.2: "But Hyrcania is exceedingly fertile, extensive, and in general level; it is distinguished by notable cities, among which are Talabroce, Samariane, Carta, and the royal residence Tape, which, they say, is situated slightly above the sea and at a distance of one thousand four hundred stadia from the Caspian Gates (some 230 km)." He continues, "According to Aristobulus, Hyrcania, which is a wooded country, has the oak... ."

In 11.7.5 Strabo writes: "This too, among the marvellous things recorded of Hyrcania, is related by Eudoxus and others: that there are some cliffs facing the sea with caverns underneath, and between these and the sea, below the cliffs, is a low-lying shore; and that rivers flowing from the precipices above rush forward with so great force that when they reach the cliffs they hurl their waters out into the sea without wetting the shore, so that even armies can pass underneath sheltered by the stream above; and the natives often come down to the place for the sake of feasting and sacrifice, and sometimes they recline in the caverns down below and sometimes they enjoy themselves basking in the sunlight beneath the stream itself, different people enjoying themselves in different ways, having in sight at the same time on either side both the sea and the shore, which latter, because of the moisture, is grassy and abloom with flowers."

Gorgan had been blessed by geography as a environmental paradise and cursed by history with the northern plague. The 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica states that Gorgan was also "a prey to the ravages of disease, principally malarial fevers due to the extensive swamps formed by waters stagnating in the forests."

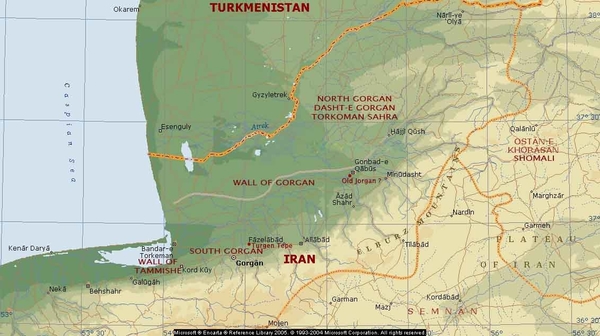

Map of the Gorgan region. The gray line running east-west just north of Gonbad-e Qabus is the wall of Gorgan.

The area to the north of the line is called the Dasht-e Gorgan, the semi-arid Plains of Gorgan. Image credit: Microsoft Encarta. Notations by K. E. Eduljee

Gorgan Map : Google

Commerce,Trade & Produce :

Strabo continues in 11.7.2: "And because of its particular kind of prosperity writers go on to relate evidences thereof: the vine produces one metretes (A little less than nine gallons) of wine, and the fig-tree sixty medimni (a medimnus was about a bushel and a half); the grain grows up from the seed that falls from the stalk; bees have their hives in the trees, and honey drips from the leaves; and this is also the case in Matiane in Media, and in Sacasene and Araxene in Armenia. There are islands in this sea which could afford a livelihood, and, according to some writers, contain gold ore."

According to 10th cent. CE writer Ibn Hawqal, Gorgon's port of Abaskun was the most important of the Caspian Sea's ports. The port was an outlet for Gorgan's exports and with Transcaucasia and the Khazar lands along the Volga (Ebn Hawqal, ed. Kramers, pp. 383, 397, Kramers and Wiet translation, II, pp. 373, 388). Many travellers used the port as well.

Gorgan was a manufacturing centre for goods the traders carried with them to other lands. Moqaddasi (p. 367) says that Gorgan's silk veils were exported as far as Yemen, and in the Hodud al-'alam (Minorsky translation, p. 133), mention is made of Gorgan's export of black silk textiles and brocades. Raw silk was also one of Gorgan's specialties. A number of Gorgan's silk products were made in Bakrabad township located on the right bank of the Gorgan River and connected to Gorgan city by a bridge of boats.

Southern and Northern Regions

The main regional centres are Gorgan city in the south and Gonbad-e Kavus/Kavous/Qabus in the north. The northern region around Gonbad-e Kavus/Qabus stretches to the Atrek River and the Turkmenistan border is known as Dasht-e Gorgan, the plain of Gorgan.

The dasht is also called the Torkoman/Torkaman Sahra (cf. Sahara), the Turkoman steppes, the grazing grounds of the Turkoman nomads.

The northern grazing grounds developed as the climate changed during the last three thousand years. Prior to the change in climate, the area received more rain and as a consequence the land that is now grassland, supported agriculture. The climate change and the consequent change to grasslands also resulted in a change in the population from farmers to herding nomads. That change brought with it hostilities between the northern and southern peoples. The south responded with the construction of a defensive wall called the wall of Gorgan which became the boundary between the grasslands of the north and the farmlands of the south.

History of Varkana and Gorgan

Turang Tapeh. Image credit: Various An archaeological site known locally as Tureng Tape (also spelt Torang/Turang/Turanga Depe/Tepe/Tappeh/Tapeh/Tappe/Tappa), the hill of the pheasants, is located 22 km (18 as the crow flies) northeast of Gorgan near Kuran Tappeh. Excavations in 1932 revealed five distinct layers, the earliest dating back to the sixth millennium BCE (the Chalcolithic or Copper Age) and the latest to between 630-1050 CE.

During the Bronze Age (second half of the third millennium and the early second millennium BCE) Tureng Tepe was one of the largest centres of north-eastern Iran yet discovered. Gold, bronze, and stone objects, dating to this time, called the Astarabad Treasure, were found at the site. The culture of Tureng Tepe during the city's zenith closely parallels that of Tepe Hissar.

The appearance of a plain grey pottery dated to the third millennium BCE has led to speculation that the change marks the entry of Aryan tribes into the region. This reasoning is highly speculative. Nevertheless, the site is evidence of an extremely old civilization that was advanced for its times, residing in the area. The tepe forms a natural link with the tepes along the northern slopes of the Kopet Dag and shares interesting connections with sites in Balkh and in the eastern Iranian plateau.

Occupied until the medieval ages, Torang was also a caravanserai, a caravan station, along the Aryan trade roads until it was destroyed during The Mongol period (1220-1380).

c 3000 BCE female figurines from Turang level IIIB. Image credit: Mary Harrsch at Flickr

Bronze Age (2nd millennium BCE) painted pottery from Turang at the Louvre Museum, Paris. Image credit: dynamosquito at Flickr

Views of Golestan. Image credit: Ali Majdfar at Panoramio

East of Gonbad-e Kavous. Image credit: Saeid Vazifehbash at Panoramio

Kalaleh, Gonbad region. Image credit: Saeid Vazifehbash at Panoramio

Kalaleh, Gonbad region. Image credit: Saeid Vazifehbash at Panoramio

Views of Golestan. Image credit: Ali Farman at Panoramio

Dawn of the Historical Age :

Strabo in 11.8.3: "Between them (Saka / Sacae) and Hyrcania and Parthia... is a great waterless desert, which they (the Saka / Sacae) traversed by long marches and then overran Hyrcania, Nesaea, and the plains of the Parthians. And these people agreed to pay tribute, and the tribute was to allow the invaders at certain appointed times to overrun the country and carry off booty. But when the invaders overran their country more than the agreement allowed, war ensued, and in turn their quarrels were composed and new wars were begun. Such is the life of the other nomads also, who are always attacking their neighbours and then in turn settling their differences."

We have previously mentioned that the region was called Varkana during the Achaemenian era (c. 650-330 BCE). We first hear of the name Varkana in the inscriptions of Darius the Great at Behistun, and where he describes the various rebellions that erupted when on September 29, 522 BCE he assumed the Persian throne after assassinating the usurper who Darius called Gaumata the Magian. By December of that year Varkana and Parthava had revolted as well. On March 8, 521, the Parthava and Varkani attacked the imperial garrison commanded by Darius' father Vishtasp (Gk. Hystaspes), but were defeated. Soon after, Darius sent reinforcements and the two kingdoms were brought under his control.

About a century later Greek historian Herodotus (c 485-420 BCE) mentions 'Hyrcania' in his Histories (3.117) when referring to an irrigation dam built by Darius. The dam had five sluice gates at the head of five channels. Another mention is in connection with 'Hyrcanian' members of Xerxes' army (7.62).

Gorgan, it appears was the name of the city-state / kingdom during Sassanian times. In other words, Shahr-e Gorgan, the City of Gorgan, was the eponymous and major city for the Gorgan region around it.

Gorgan came to be known as Astarabad / Estrabad during the Islamic era. However, some accounts state that in medieval times, Old Gorgan city and Astarabad were two separate cities, with Astarabad lying west of Old Gorgan city. During the reign of Shah Abbas (1588-1639), the Gorgan region formally came to be known as Astarabad province (eyalat). The city and province formally reverted back to being called Gorgan in 1937 during the Pahlavi era.

Greek historian Arrian, recording the Macedonian invader Alexander's expedition to the East, speaks of Alexander's march to the city of Zadracarta (Today's Sari, Mazandaran?), the largest town in the region and the capital of Hyrcania. Zadracarta was also where the royal palace for the ruler of Hyrcania was situated. In trying to locate the ancient capital, archaeologists and historians have suggested that its ruins are now called Qal'a-e Kandan, a site covered by a large tepe, an earthen mound about 40m in height and some 300 x 220 m in area, located on the southwest corner of the city of Gorgan on the road to Sari.

Abu'l-Fazl Bayhaqi's in Fayyaz (p. 585) states that during his expedition to the Caspian coast, the Ghaznavid Sultan Mas'ud I's (1031-1041) tent was pitched on a high place (bala) outside Estrabad. This 'bala' is thought of as being the tepe Qal'a-e Kandan outside today's Gorgan city. If this suggestion is correct then the fact that Qal'a-e Kandan had already become a tepe in the 11th century CE, further suggests that the site must date from the pre-Islamic period, since it had already become entombed in a hill of soil by the time of the Ghaznavid sultan's visit, thereby enhancing the tepe's candidature as the ancient Zadracarta.

Arab invaders commanded by Sa'id bin 'As arrived at Gorgan in 650-51 CE. The then malek (Sasanian marzban?) of Gorgan agreed to pay the Arabs a tribute of 200,000 dirhams (Baladori, Fotuh, pp. 334-35). The Arabs regarded Gorgan and neighbouring Dahistan as togur, i.e. frontier regions, against the Turks and the Gozz of the Trans-Caspian steppes.

Old Gorgan city was Arabized as Jorgan (Markwart, Eranshahr, p. 72).

In the beginning of the 13th century CE, the Mongols devastated the region and massacred the population, bringing to an end its legendary prosperity. The Gorgan city and its surrounding region suffered yet further from Timur's ravages. After Timur, an rebuilding started and Astarabad developed as the main urban center.

Various Turkmen tribes established themselves in Gorgan during the Safavid period and in the late 17th and the 18th century Gorgan became the power base for the Turkmen Qajar.

By the 17th century, the Russians became the great threat from the north. In the early 18th century, the Russian armies of Peter the Great occupied Gorgan and established a trading post there for a short period.

As well, the region continued to experience Turkmen incursions from the steppes until the late 19th century. The 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica states "the frequent incursions of the Goklan and Yomut Turkomans, who have their camping-grounds in the northern part of the province, and until about 1890 plundered caravans sometimes at the very gates of Astarabad (Gorgan) city, and carried people off into slavery and bondage."

The encyclopaedia also describes Astarabad (Gorgan) city as, c. 1910, "surrounded by a mud wall about 30 feet in height and about 31 miles in circuit, but much of the enclosed space is occupied by gardens, mounds of refuse, and ruins. At one time of greater size, it was reduced by Nadir Shah within its present limits. ...Owing to the noxious exhalations of the surrounding forests the town is so extremely unhealthy during the hot weather as to have acquired the title of the 'Abode of the Plague.'"

The region began to see some measure of peace and prosperity in the 1920s and 30s.

Dasht-e Gorgan's Change to the Torkoman Sahra

It would seem, that as the climate became more arid and landscape changed to grasslands, the population characteristic changed as well - from the more settled Iranian Aryans to the more nomadic Turkoman nomads from the north and northeast. The early, more humid climate supported forested areas and a larger variety of wildlife (Johann Wolfgang Amschler, Tierreste: Die Ausgrabungen von dem "Grossen Königshügel" Shah Tepe, in Nord-Iran, Stockholm, 1939, pp. 35-129).

Archaeological findings in 1963-68 reported by E. W. Crawford and J. Deshayes indicate settlements dating back to the sixth millennium BCE.

As the climate changed about three thousand years ago, the settled Iranian-Aryan communities moved further south and west gradually being replaced by the nomads.

Ture Johnsson Arne recorded 233 archaeological sites on the Gorgan plain. These sites have yielded evidence from the Parthian and Sassanian eras.

The settled and nomadic communities were different in every way - from lifestyle, diet, appearance and ethical systems. A striking and visible difference is their dwellings. The dwellings of the nomads were the typical portable Central Asian yurt-like round tents called the kibitka or alachiq. The dwellings were designed to be quickly packed, easily moved to another dwelling or grazing area. The nomadic group encampments were called oba.

The nomadic communities continued a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and eventually occupied themselves with animal husbandry and rearing herds with which they moved when seeking fresh pastures.

At some point, carpet weaving become a significant occupation for many Turkoman households producing the famed Bukhara rugs. It was a portable occupation that used the wool of their camels, sheep, and goats. Carpet production would inevitably have involved the nomads in some aspect of trading.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |