| IRANI RENAISSANCE THE BENEFACTORS Irani

Zoroastrian Renaissance. The Benefactors.

Irani

Zoroastrians of India & Iran :

The Story of Firouzeh. Early 18th Century :

By way of background, the Dorabji family were among the early Parsi inhabitants of Bombay. In 1692 CE, when the British garrison of Bombay had been decimated by a cholera epidemic, Rustamji (also spelt Rastamji) Dorabji rallied the Koli fisherman and other residents to defend Bombay from an attack by the Muslim Sidi of Janjira. In recognition of his leadership and valour, the British appointed Rustamji (Rastamji) with the hereditary title of patel or chief, a position that carried the authority of collecting taxes from the residents.

Rustamji Dorabji Patel's wife was a refugee from Iran, Firouzeh. Firouzeh's Iranian parents had been forcibly converted to Islam. Unable to escape, they sought nevertheless to save their two daughters from their fate. They were fortunate that a German traveller agreed to take the girls with him to safety to the newly established port of Bombay. Firouzeh met Rustamji Dorabji while under the care of Bhikhaji Beramji Panday [D. F. Karaka, History of the Parsis (London, 1884), Vol. II, p. 52 n.]. Bhikhaji Beramji Panday was the father of Framji Bhikhaji Panday who would marry another Irani Zoroastrian refugee, Golestan.

The Story of Golestan. Early 19th Century Benefactors Rise

to the Occasion :

The Bombay Parsees welcomed Golestan and her father into their circles and affectionately called Golestan 'Gulbai Velatan' or 'Gulbai the foreigner'. Helped by the Lashkari family, Khusrau-i Yazdyar returned to Yazd three times and eventually succeeded in bringing his whole family to Gujarat.

After father Khusrau and daughter Golestan had settled down in their new home, Golestan met a Parsee merchant Framji Bhikhaji Panday.

Framji

Bhikaji Panday - the Father of Irani Zoroastrians of India :

Framji, upon hearing about the plight of Iranian Zoroastrians from his wife and father-in-law, decided to help his co-religionists of Iran "with body, mind and money". One of Framji's first acts was to assist other Iranis flee the hell in which they were living. Upon the arrival of the Zoroastrian refugees in India, Framji helped them settled down to a new life of hope. For his service to the Iranian Zoroastrian refugees, they gave Framji the title 'father of Irani Zoroastrians of India'.

Society for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Zoroastrians

in Persia :

In a document signed on February 24, 1882, the signing officers of the society were Dinshaw Manockji Petit, Nusserwanji Manockji Petit, Cursetji Nusserwanji Cama (honorary treasurer), Bomanji Framji Cama, K. R. Cama, Eduljee Bomanji Morris, Nusserwanji Meherwanji Panday (presumably Meherwanji Panday's son), Muncherji Cowasji Shapoorji, Eduljee Nusserwanji Settna. Later, Pestonji Marker, founder of Yazd's Marker schools, would become one of the society's most munificent supporters.

Among it various projects, notably those initiated through Maneckji Hataria, the society also financed the translation of the Avesta into Persian by the noted scholar Pour-e Dawoud.

Maneckji Limji Hataria (1813-1890 CE) :

One of the first resolutions of the society was to send an an emissary to Iran and they were very fortunate to recruit the indomitable Maneckji Limji Hataria. Hataria, a travelling commercial representative, was born at the village of Mora Sumali near Surat in 1813 CE. He began to earn a living at the age of fifteen. His father was Limji Hushang Hataria.

If the concept of finding one's khvarenah, a calling, is valid, then Hataria was about to find his. In doing so, if there is an modern-day example of an ashavan, it was Maneckji Limji Hataria. Hataria would be an agent, indeed a warrior, for positive change.

Maneckji's

Journey to Iran :

At the outset we should note that Hataria mission to Iran was not without risk to his person. While journeying in Iran, he and his son Hormuzdiar were both threatened with death, and they took to travelling well armed. However, despite being armed, he still, as he records, had "to part with goods to save (his) life."

Hataria

travelled by ship from Bombay to the port of Bushehr in Iran via

the island of Hormoz. From the port of Bushehr in the Persian Gulf,

Hataria made his way through Firozabad to Shiraz. All along the

took of ancient forts, dakhma and fire temples, stopping at various

sites such as Persepolis and Naqsh-e Rostam enroute to Yazd.

Hataria Petitions Qajar Government :

Education - a First Priority :

Of all the changes he introduced, this farsighted and simple act laid the foundation of a Zoroastrian renaissance. For the world was entering an information age. As a result of this Zoroastrian emphasis on a good education, Zoroastrians today make up one of the most educated communities in the world.

Wherever he went, Hataria started to light fires - in temples, in schools, in minds and in hearts.

Infrastructure Projects :

Individual Financial & Work Assistance :

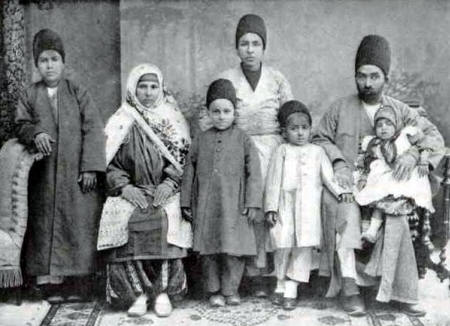

Zoroastrian family in Tehran 1910 CE (towards the end of the Qajar era). Photo credit: Wikipedia

Change for the Better :

Irani Benefactors The Anjuman-e Zartoshtian Charitable Organizations

:

House of Mehr :

In Elabad village where the family owned property, brothers Rostam built the fire temple, Kay Khosrow built the dakhma, while Godarz built the school and ab-anbar, the water tank (which benefited the Muslim residents of Elabad as well). Godarz also provided the land for a hospital run by Christian missionaries. The schools, water tanks and hospitals were available from everyone in need without religious or ethnic distinction.

In

the 1950s, the Firuzgar family founded a hospital which was later

taken over by Iran's Ministry of Health.

Jahanians :

Arbab Rustam Guiv :

Morvarid and Arbab Rostam Guiv Arbab Rustam Guiv (1888-1980 CE) was a native of Yazd. His father Shahpur Guiv had a business in Yazd selling local hand made cloth. Arbab Guiv moved to Tehran to join his brother and made his fortune in trading, manufacturing and land. He converted a 150 to 200 acre parcel of fallow land at the foot of the Damavand mountain, some hundred kilometres north of Tehran, into fertile land where he cultivated fruits, vegetables and grain. He called his oasis Rustamabad. He added to his land holdings by purchasing another tract of land ten kilometres from Rustamabad.

During a 1953 trip to India, Arbab Guiv was very impressed with the housing colonies built for low and middle income Zoroastrians by wealthy benefactors. He was particularly impressed by Khosrow Bagh in Colaba, Bombay (Mumbai) and used it as a model for constructing a housing colony for Iranian Zoroastrians in Tehran. With this in mind, he purchased at a reduced cost fifteen acres of a new development by the Tafti and Aresh families in the north-east of Tehran, called Tehran Pars. On the land he purchased, Arbab Guiv a housing colony of 80 duplexes (160 units) called Rustam Bagh (or Rostam Baug). The units were then made available for low and middle income Zoroastrians. The colony included gardens, a community hall, library, school, sports ground and fire temple.

Arbab Guiv had now firmly established his desire to serve the community. In Yazd, he funded the building of an ab-anbar, a community water storage facility. His factories and businesses provided employment to Zoroastrians, his colonies provided housing and his schools provided education. in his later years, he turned his attention to providing funds for immigrant Zoroastrians in Europe, North America and Australia build a spiritual home, places of worship called Darbe Mehrs. This writer was a trustee of a Arbab Rostam Guiv Darbe Mehr in Burnaby (in Greater Vancouver), Canada.

Other Irani Benefactors :

Yazd's gahanbar-khana, a large hall that could accommodate the community during the gahanbars or seasonal feasts was constructed in the 1930s by Rostam Khosrow Sedayat, a merchant of priestly family. In Kerman, Soroush Shahriyar started the Soroushian family charities. In the 40s, the family donated land for a new burial ground which they continue to maintain.

Least We Forget :

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |