| GILGAMESH

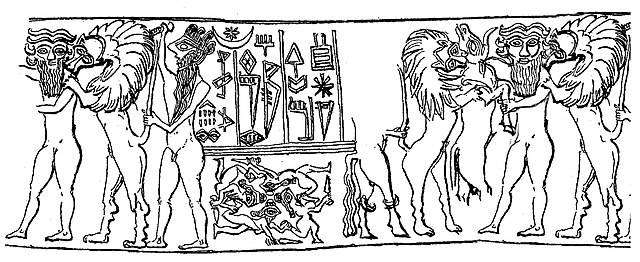

Possible representation of Gilgamesh as Master of Animals, grasping a lion in his left arm and snake in his right hand, in an Assyrian palace relief (713–706 BC), from Dur-Sharrukin, now held in the Louvre Predecessor

: Dumuzid, the Fisherman (as Ensi of Uruk), Aga of Kish

(as King of Sumer)

Gilgamesh was a major hero in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem written in Akkadian during the late 2nd millennium BC. He was also most likely a historical king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, who was posthumously deified. His rule probably would have taken place sometime between 2800 and 2500 BC, though he became a major figure in Sumerian legend during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC).

Tales of Gilgamesh's legendary exploits are narrated in five surviving Sumerian poems. The earliest of these is most likely "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld", in which Gilgamesh comes to the aid of the goddess Inanna and drives away the creatures infesting her huluppu tree. She gives him two unknown objects, a mikku and a pikku, which he loses. After Enkidu's death, his shade tells Gilgamesh about the bleak conditions in the Underworld. The poem "Gilgamesh and Agga" describes Gilgamesh's revolt against his overlord King Agga. Other Sumerian poems relate Gilgamesh's defeat of the ogre Huwawa and the Bull of Heaven, while a fifth, poorly preserved poem apparently describes his death and funeral.

In later Babylonian times, these stories began to be woven into a connected narrative. The standard Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh was composed by a scribe named Sîn-leqi-unninni, probably during the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1600 – c. 1155), based on much older source material. In the epic, Gilgamesh is a demigod of superhuman strength who befriends the wildman Enkidu. Together, they go on adventures, defeating Humbaba (Sumerian: Huwawa) and the Bull of Heaven, who is sent to attack them by Ishtar (Sumerian: Inanna) after Gilgamesh rejects her offer for him to become her consort. After Enkidu dies of a disease sent as punishment from the gods, Gilgamesh becomes afraid of his own death, and visits the sage Utnapishtim, the survivor of the Great Flood, hoping to find immortality. Gilgamesh repeatedly fails the trials set before him and returns home to Uruk, realizing that immortality is beyond his reach.

Most classical historians agree that the Epic of Gilgamesh exerted substantial influence on both the Iliad and the Odyssey, two epic poems written in ancient Greek during the 8th century BC. The story of Gilgamesh's birth is described in an anecdote from On the Nature of Animals by the Greek writer Aelian (2nd century AD). Aelian relates that Gilgamesh's grandfather kept his mother under guard to prevent her from becoming pregnant, because he had been told by an oracle that his grandson would overthrow him. She became pregnant and the guards threw the child off a tower, but an eagle rescued him mid-fall and delivered him safely to an orchard, where he was raised by the gardener.

The Epic of Gilgamesh was rediscovered in the Library of Ashurbanipal in 1849. After being translated in the early 1870s, it caused widespread controversy due to similarities between portions of it and the Hebrew Bible. Gilgamesh remained mostly obscure until the mid-20th century, but, since the late 20th century, he has become an increasingly prominent figure in modern culture.

Historical king :

Seal

impression of "Mesannepada, king of Kish", excavated in

the Royal Cemetery at Ur (U. 13607), dated circa 2600 BC. The seal

shows Gilgamesh and the mythical bull between two lions, one of

the lions biting him in the shoulder. On each side of this group

appears Enkidu and a hunter-hero, with a long beard and a Kish-style

headdress, armed with a dagger. Under the text, four runners with

beard and long hair form a human Swastika. They are armed with daggers

and catch each other's foot.

For a second time, the Tummal fell into ruin,

Gilgamesh is also referred to as a king by King Enmebaragesi of Kish, a known historical figure who may have lived near Gilgamesh's lifetime. Furthermore, Gilgamesh is listed as one of the kings of Uruk by the Sumerian King List. Fragments of an epic text found in Mê-Turan (modern Tell Haddad) relate that at the end of his life Gilgamesh was buried under the river bed. The people of Uruk diverted the flow of the Euphrates passing Uruk for the purpose of burying the dead king within the river bed.

Deification

and legendary exploits :

Sculpted scene depicting Gilgamesh wrestling with animals. From the Shara temple at Tell Agrab, Diyala Region, Iraq. Early Dynastic period, 2600–2370 BC. On display at the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad.

Mace dedicated to Gilgamesh, with transcription of the name Gilgamesh in standard Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform, Ur III period, between 2112 and 2004 BC It is certain that, during the later Early Dynastic Period, Gilgamesh was worshipped as a god at various locations across Sumer. In 21st century BC, King Utu-hengal of Uruk adopted Gilgamesh as his patron deity. The kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC) were especially fond of Gilgamesh, calling him their "divine brother" and "friend." King Shulgi of Ur (2029–1982 BC) declared himself the son of Lugalbanda and Ninsun and the brother of Gilgamesh. Over the centuries, there may have been a gradual accretion of stories about Gilgamesh, some possibly derived from the real lives of other historical figures, such as Gudea, the Second Dynasty ruler of Lagash (2144–2124 BC). Prayers inscribed in clay tablets address Gilgamesh as a judge of the dead in the Underworld.

Gilgamesh,

Enkidu, and the Netherworld :

Gilgamesh, who in this story is portrayed as Inanna's brother, comes along and slays the serpent, causing the Anzû-bird and Lilitu to flee. Gilgamesh's companions chop down the tree and carve its wood into a bed and a throne, which they give to Inanna. Inanna responds by fashioning a pikku and a mikku (probably a drum and drumsticks respectively, although the exact identifications are uncertain), which she gives to Gilgamesh as a reward for his heroism. Gilgamesh loses the pikku and mikku and asks who will retrieve them. Enkidu descends to the Underworld to find them, but disobeys the strict laws of the Underworld and is therefore required to remain there forever. The remaining portion of the poem is a dialogue in which Gilgamesh asks the shade of Enkidu questions about the Underworld.

Subsequent

poems :

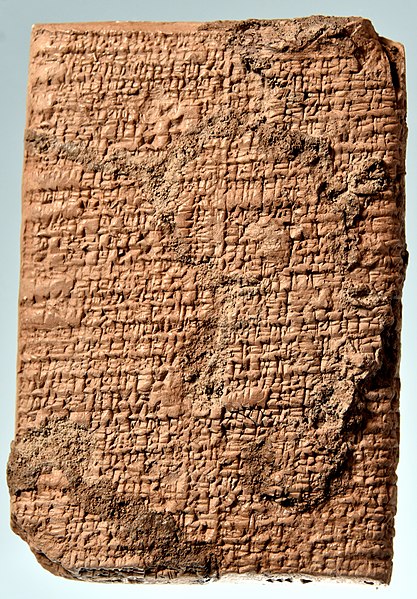

Story of "Gilgamesh and Agga". Old Babylonian period, from southern Iraq. Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq "Gilgamesh and Agga" describes Gilgamesh's successful revolt against his overlord Agga, the king of the city-state of Kish."Gilgamesh and Huwawa" describes how Gilgamesh and his servant Enkidu, aided by the help of fifty volunteers from Uruk, defeat the monster Huwawa, an ogre appointed by the god Enlil, the ruler of the gods, as the guardian of the Cedar Forest. In "Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven", Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the Bull of Heaven, who has been sent to attack them by the goddess Inanna. The plot of this poem differs substantially from the corresponding scene in the later Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. In the Sumerian poem, Inanna does not seem to ask Gilgamesh to become her consort as she does in the later Akkadian epic. Furthermore, while she is coercing her father An to give her the Bull of Heaven, rather than threatening to raise the dead to eat the living as she does in the later epic, she merely threatens to let out a "cry" that will reach the earth. A poem known as the "Death of Gilgamesh" is very poorly preserved, but appears to describe a major state funeral followed by the arrival of the deceased in the Underworld. It is possible that the modern scholars who gave the poem its title may have misinterpreted it, and the poem may actually be about the death of Enkidu.

Epic of Gilgamesh :

The ogre Humbaba, shown in this terracotta plaque from the Old Babylonian Period, is one of the opponents fought by Gilgamesh and his companion Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh

Ancient Mesopotamian terracotta relief (c. 2250 — 1900 BC) showing Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven, an episode described in Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh Eventually, according to Kramer (1963)

Gilgamesh became the hero par excellence of the ancient world—an adventurous, brave, but tragic figure symbolizing man's vain but endless drive for fame, glory, and immortality.

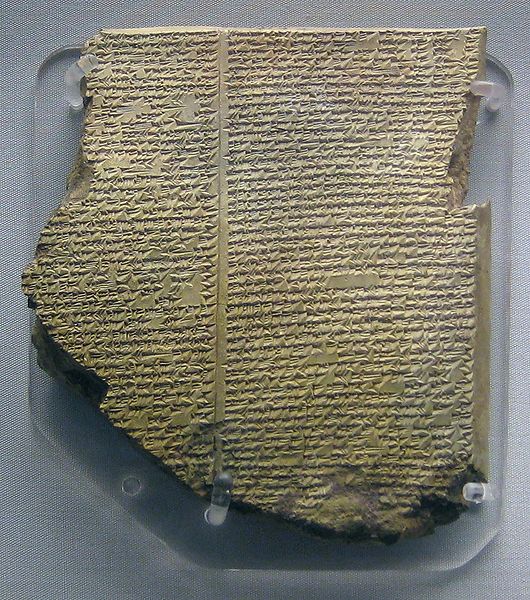

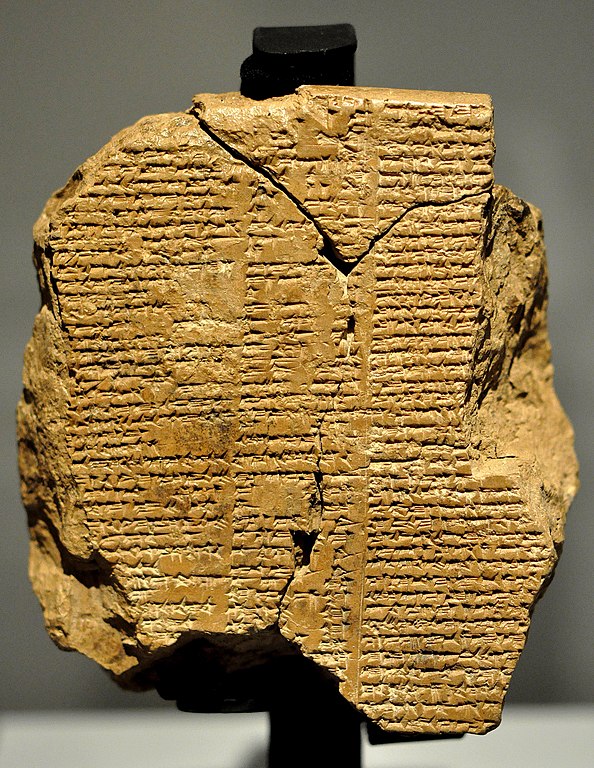

By the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 – c. 1531 BC), stories of Gilgamesh's legendary exploits had been woven into one or several long epics. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the most complete account of Gilgamesh's adventures, was composed in Akkadian during the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1600 – c. 1155 BC) by a scribe named Sîn-leqi-unninni. The most complete surviving version of the Epic of Gilgamesh is recorded on a set of twelve clay tablets dating to the seventh century BC, found in the Library of Ashurbanipal in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. The epic survives only in a fragmentary form, with many pieces of it missing or damaged. Some scholars and translators choose to supplement the missing parts of the epic with material from the earlier Sumerian poems or from other versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh found at other sites throughout the Near East.

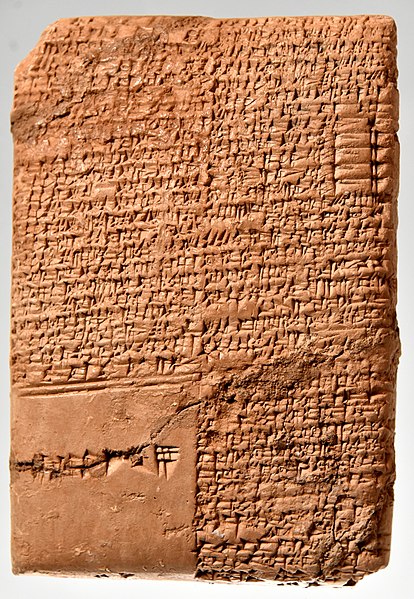

Tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq In the epic, Gilgamesh is introduced as "two thirds divine and one third mortal." At the beginning of the poem, Gilgamesh is described as a brutal, oppressive ruler. This is usually interpreted to mean either that he compels all his subjects to engage in forced labor or that he sexually oppresses all his subjects. As punishment for Gilgamesh's cruelty, the god Anu creates the wildman Enkidu. After being tamed by a prostitute named Shamhat, Enkidu travels to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh. In the second tablet, the two men wrestle and, although Gilgamesh wins the match in the end, he is so impressed by his opponent's strength and tenacity that they become close friends. In the earlier Sumerian texts, Enkidu is Gilgamesh's servant, but, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, they are companions of equal standing.

In tablets III through IV, Gilgamesh and Enkidu travel to the Cedar Forest, which is guarded by Humbaba (the Akkadian name for Huwawa). The heroes cross the seven mountains to the Cedar Forest, where they begin chopping down trees. Confronted by Humbaba, Gilgamesh panics and prays to Shamash (the East Semitic name for Utu), who blows eight winds in Humbaba's eyes, blinding him. Humbaba begs for mercy, but the heroes decapitate him regardless. Tablet VI begins with Gilgamesh returning to Uruk, where Ishtar (the Akkadian name for Inanna) comes to him and demands him to become her consort. Gilgamesh repudiates her, insisting that she has mistreated all her former lovers.

In revenge, Ishtar goes to her father Anu and demands that he give her the Bull of Heaven, which she sends to attack Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull and offer its heart to Shamash. While Gilgamesh and Enkidu are resting, Ishtar stands up on the walls of Uruk and curses Gilgamesh. Enkidu tears off the Bull's right thigh and throws it in Ishtar's face, saying, "If I could lay my hands on you, it is this I should do to you, and lash your entrails to your side." Ishtar calls together "the crimped courtesans, prostitutes and harlots" and orders them to mourn for the Bull of Heaven. Meanwhile, Gilgamesh holds a celebration over the Bull of Heaven's defeat.

Tablet VII begins with Enkidu recounting a dream in which he saw Anu, Ea, and Shamash declare that either Gilgamesh or Enkidu must die as punishment for having slain the Bull of Heaven. They choose Enkidu and Enkidu soon grows sick. He has a dream of the Underworld and then he dies. Tablet VIII describes Gilgamesh's inconsolable grief over his friend's death and the details of Enkidu's funeral. Tablets IX through XI relate how Gilgamesh, driven by grief and fear of his own mortality, travels a great distance and overcomes many obstacles to find the home of Utnapishtim, the sole survivor of the Great Flood, who was rewarded with immortality by the gods.

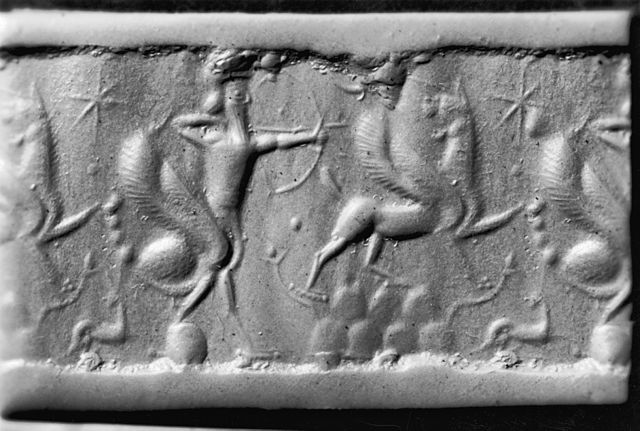

Early Middle Assyrian cylinder seal impression dating between 1400

and 1200 BC, showing a man with bird wings and a scorpion tail firing

an arrow at a griffin on a hillock. A scorpion man is among the

creatures Gilgamesh encounters on his journey to the homeland of

Utnapishtim.

Next, Utnapishtim tells him that, even if he cannot obtain immortality, he can restore his youth using a plant with the power of rejuvenation. Gilgamesh takes the plant, but leaves it on the shore while swimming and a snake steals it, explaining why snakes are able to shed their skins. Despondent at this loss, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk, and shows his city to the ferryman Urshanabi. It is at that this point that the epic stops being a coherent narrative. Tablet XII is an appendix corresponding to the Sumerian poem of Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld describing the loss of the pikku and mikku.

Numerous elements within this narrative reveal lack of continuity with the earlier portions of the epic. At the beginning of Tablet XII, Enkidu is still alive, despite having previously died in Tablet VII, and Gilgamesh is kind to Ishtar, despite the violent rivalry between them displayed in Tablet VI. Also, while most of the parts of the epic are free adaptations of their respective Sumerian predecessors, Tablet XII is a literal, word-for-word translation of the last part of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld. For these reasons, scholars conclude this narrative was probably relegated to the end of the epic because it did not fit the larger narrative. In it, Gilgamesh sees a vision of Enkidu's ghost, who promises to recover the lost items and describes to his friend the abysmal condition of the Underworld.

In

Mesopotamian art :

Later

influence :

The episode involving Odysseus's confrontation with Polyphemus in the Odyssey, shown in this seventeenth-century painting by Guido Reni, bears similarities to Gilgamesh and Enkidu's battle with Humbaba in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Indus valley civilization seal, with the Master of Animals motif of a man fighting two lions (2500–1500 BC), similar to the Sumerian "Gilgamesh" motif, an indicator of Indus-Mesopotamia relations The Epic of Gilgamesh exerted substantial influence on the Iliad and the Odyssey, two epic poems written in ancient Greek during the eighth century BC. According to Barry B. Powell, an American classical scholar, early Greeks were probably exposed to Mesopotamian oral traditions through their extensive connections to the civilizations of the ancient Near East and this exposure resulted in the similarities that are seen between the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Homeric epics. Walter Burkert, a German classicist, observes that the scene in Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Gilgamesh rejects Ishtar's advances and she complains before her mother Antu, but is mildly rebuked by her father Anu, is directly paralleled in Book V of the Iliad. In this scene, Aphrodite, the later Greek adaptation of Ishtar, is wounded by the hero Diomedes and flees to Mount Olympus, where she cries to her mother Dione and is mildly rebuked by her father Zeus.

Powell observes that the opening lines of the Odyssey seem to echo the opening lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The storyline of the Odyssey likewise bears numerous similarities to that of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Both Gilgamesh and Odysseus encounter a woman who can turn men into animals: Ishtar (for Gilgamesh) and Circe (for Odysseus). In the Odyssey, Odysseus blinds a giant Cyclops named Polyphemus, an incident which bears similarities to Gilgamesh's slaying of Humbaba in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Both Gilgamesh and Odysseus visit the Underworld and both find themselves unhappy whilst living in an otherworldly paradise in the presence of an attractive woman: Siduri (for Gilgamesh) and Calypso (for Odysseus). Finally, both heroes have an opportunity for immortality but miss it (Gilgamesh when he loses the plant, and Odysseus when he leaves Calypso's island).

In the Qumran scroll known as Book of Giants (c. 100 BC) the names of Gilgamesh and Humbaba appear as two of the antediluvian giants, rendered (in consonantal form) as glgmš and wbbyš. This same text was later used in the Middle East by the Manichaean sects, and the Arabic form Gilgamish/Jiljamish survives as the name of a demon according to the Egyptian cleric Al-Suyuti (c. 1500).

The story of Gilgamesh's birth is not recorded in any extant Sumerian or Akkadian text, but a version of it is described in De Natura Animalium (On the Nature of Animals) 12.21, a commonplace book which was written in Greek sometime around 200 AD by the Hellenized Roman orator Aelian. According to Aelian's story, an oracle told King Seuechoros of the Babylonians that his grandson Gilgamos would overthrow him. To prevent this, Seuechoros kept his only daughter under close guard at the Acropolis of the city of Babylon, but she became pregnant nonetheless. Fearing the king's wrath, the guards hurled the infant off the top of a tall tower. An eagle rescued the boy in midflight and carried him to an orchard, where it carefully set him down. The caretaker of the orchard found the boy and raised him, naming him Gilgamos. Eventually, Gilgamos returned to Babylon and overthrew his grandfather, proclaiming himself king. The birth narrative described by Aelian is in the same tradition as other Near Eastern birth legends, such as those of Sargon, Moses, and Cyrus. Theodore Bar Konai (c. AD 600), writing in Syriac, also mentions a king Gligmos, Gmigmos or Gamigos as last of a line of twelve kings who were contemporaneous with the patriarchs from Peleg to Abraham; this occurrence is also considered a vestige of Gilgamesh's former memory.

Modern rediscovery :

In 1880, the English Assyriologist George Smith (left) published

a translation of Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh (right), containing

the Flood myth, which attracted immediate scholarly attention and

controversy due to its similarity to the Genesis flood narrative.

Early interest in the Epic of Gilgamesh was almost exclusively on account of the flood story from Tablet XI. The flood story attracted enormous public attention and drew widespread scholarly controversy, while the rest of the epic was largely ignored. Most attention towards the Epic of Gilgamesh in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came from German-speaking countries, where controversy raged over the relationship between Babel und Bibel ("Babylon and Bible").

In January 1902, the German Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch gave a lecture at the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin in front of the Kaiser and his wife, in which he argued that the Flood story in the Book of Genesis was directly copied off the one in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Delitzsch's lecture was so controversial that, by September 1903, he had managed to collect 1,350 short articles from newspapers and journals, over 300 longer ones, and twenty-eight pamphlets, all written in response to this lecture, as well as another lecture about the relationship between the Code of Hammurabi and the Law of Moses in the Torah. These articles were overwhelmingly critical of Delitzsch. The Kaiser distanced himself from Delitzsch and his radical views and, in fall of 1904, Delitzsch was forced to give his third lecture in Cologne and Frankfurt am Main rather than in Berlin. The putative relationship between the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Hebrew Bible later became a major part of Delitzsch's argument in his 1920–21 book Die große Täuschung (The Great Deception) that the Hebrew Bible was irredeemably "contaminated" by Babylonian influence and that only by eliminating the human Old Testament entirely could Christians finally believe in the true, Aryan message of the New Testament.

Early modern interpretations :

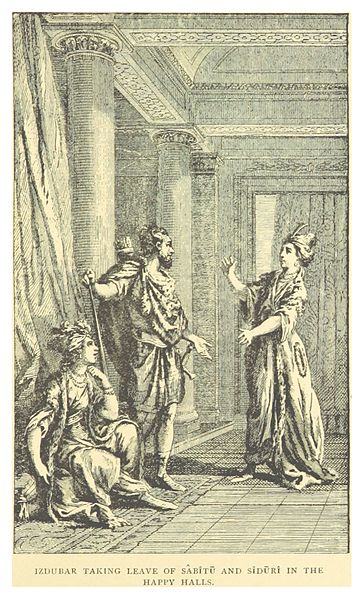

Illustration of Izdubar (Gilgamesh) in a scene from the book-length poem Ishtar and Izdubar (1884) by Leonidas Le Cenci Hamilton, the first modern literary adaptation of the Epic of Gilgamesh The first modern literary adaptation of the Epic of Gilgamesh was Ishtar and Izdubar (1884) by Leonidas Le Cenci Hamilton, an American lawyer and businessman. Hamilton had rudimentary knowledge of Akkadian, which he had learned from Archibald Sayce's 1872 Assyrian Grammar for Comparative Purposes. Hamilton's book relied heavily on Smith's translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh, but also made major changes. For instance, Hamilton omitted the famous flood story entirely and instead focused on the romantic relationship between Ishtar and Gilgamesh. Ishtar and Izdubar expanded the original roughly 3,000 lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh to roughly 6,000 lines of rhyming couplets grouped into forty-eight cantos. Hamilton significantly altered most of the characters and introduced entirely new episodes not found in the original epic. Significantly influenced by Edward FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia, Hamilton's characters dress more like nineteenth-century Turks than ancient Babylonians. Hamilton also changed the tone of the epic from the "grim realism" and "ironic tragedy" of the original to a "cheery optimism" filled with "the sweet strains of love and harmony".

In his 1904 book Das Alte Testament im Lichte des alten Orients, the German Assyriologist Alfred Jeremias equated Gilgamesh with the king Nimrod from the Book of Genesis and argued that Gilgamesh's strength must come from his hair, like the hero Samson in the Book of Judges, and that he must have performed Twelve Labors like the hero Heracles in Greek mythology. In his 1906 book Das Gilgamesch-Epos in der Weltliteratur, the Orientalist Peter Jensen declared that the Epic of Gilgamesh was the source behind nearly all the stories in the Old Testament, arguing that Moses is "the Gilgamesh of Exodus who saves the children of Israel from precisely the same situation faced by the inhabitants of Erech at the beginning of the Babylonian epic." He then proceeded to argue that Abraham, Isaac, Samson, David, and various other biblical figures are all nothing more than exact copies of Gilgamesh. Finally, he declared that even Jesus is "nothing but an Israelite Gilgamesh. Nothing but an adjunct to Abraham, Moses, and countless other figures in the saga." This ideology became known as Panbabylonianism and was almost immediately rejected by mainstream scholars. The most stalwart critics of Panbabylonianism were those associated with the emerging Religionsgeschichtliche Schule. Hermann Gunkel dismissed most of Jensen's purported parallels between Gilgamesh and biblical figures as mere baseless sensationalism. He concluded that Jensen and other Assyriologists like him had failed to understand the complexities of Old Testament scholarship and had confused scholars with "conspicuous mistakes and remarkable aberrations".

In English-speaking countries, the prevailing scholarly interpretation during the early twentieth century was one originally proposed by Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, which held that Gilgamesh is a "solar hero", whose actions represent the movements of the sun, and that the twelve tablets of his epic represent the twelve signs of the Babylonian zodiac. The Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, drawing on the theories of James George Frazer and Paul Ehrenreich, interpreted Gilgamesh and Eabani (the earlier misreading for Enkidu) as representing "man" and "crude sensuality" respectively. He compared them to other brother-figures in world mythology, remarking, "One is always weaker than the other and dies sooner. In Gilgamesh this ages-old motif of the unequal pair of brothers served to represent the relationship between a man and his libido." He also saw Enkidu as representing the placenta, the "weaker twin" who dies shortly after birth. Freud's friend and pupil Carl Jung frequently discusses Gilgamesh in his early work Symbole der Wandlung (1911–1912). He, for instance, cites Ishtar's sexual attraction to Gilgamesh as an example of the mother's incestuous desire for her son, Humbaba as an example of an oppressive father-figure whom Gilgamesh must overcome, and Gilgamesh himself as an example of a man who forgets his dependence on the unconscious and is punished by the "gods", who represent it.

Modern interpretations and cultural significance :

Existential

angst during the aftermath of World War II significantly contributed

to Gilgamesh's rise in popularity in the middle of the twentieth

century. For instance, the German novelist Hermann Kasack used Enkidu's

vision of the Underworld from the Epic of Gilgamesh as a metaphor

for the bombed-out city of Hamburg (pictured above) in his 1947

novel Die Stadt hinter dem Strom.

The Quest of Gilgamesh, a 1953 radio play by Douglas Geoffrey Bridson, helped popularize the epic in Britain. In the United States, Charles Olson praised the epic in his poems and essays and Gregory Corso believed that it contained ancient virtues capable of curing what he viewed as modern moral degeneracy. The 1966 postfigurative novel Gilgamesch by Guido Bachmann became a classic of German "queer literature" and set a decades-long international literary trend of portraying Gilgamesh and Enkidu as homosexual lovers. This trend proved so popular that the Epic of Gilgamesh itself is included in The Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature (1998) as a major early work of that genre. In the 1970s and 1980s, feminist literary critics analyzed the Epic of Gilgamesh as showing evidence for a transition from the original matriarchy of all humanity to modern patriarchy. As the Green Movement expanded in Europe, Gilgamesh's story began to be seen through an environmentalist lens, with Enkidu's death symbolizing man's separation from nature.

A modern statue of Gilgamesh stands at the University of Sydney Theodore Ziolkowski, a scholar of modern literature, states, that "unlike most other figures from myth, literature, and history, Gilgamesh has established himself as an autonomous entity or simply a name, often independent of the epic context in which he originally became known. (As analogous examples one might think, for instance, of the Minotaur or Frankenstein's monster.)" The Epic of Gilgamesh has been translated into many major world languages and has become a staple of American world literature classes. Many contemporary authors and novelists have drawn inspiration from it, including an American avant-garde theater collective called "The Gilgamesh Group" and Joan London in her novel Gilgamesh (2001). The Great American Novel (1973) by Philip Roth features a character named "Gil Gamesh", who is the star pitcher of a fictional 1930s baseball team called the "Patriot League".

Starting in the late twentieth century, the Epic of Gilgamesh began to be read again in Iraq. Saddam Hussein, the former President of Iraq, had a lifelong fascination with Gilgamesh. Hussein's first novel Zabibah and the King (2000) is an allegory for the Gulf War set in ancient Assyria that blends elements of the Epic of Gilgamesh and the One Thousand and One Nights. Like Gilgamesh, the king at the beginning of the novel is a brutal tyrant who misuses his power and oppresses his people, but, through the aid of a commoner woman named Zabibah, he grows into a more just ruler. When the United States pressured Hussein to step down in February 2003, Hussein gave a speech to a group of his generals posing the idea in a positive light by comparing himself to the epic hero.

Scholars like Susan Ackerman and Wayne R. Dynes have noted that the language used to describe Gilgamesh's relationship with Enkidu seems to have homoerotic implications. Ackerman notes that, when Gilgamesh veils Enkidu's body, Enkidu is compared to a "bride". Ackerman states, "that Gilgamesh, according to both versions, will love Enkidu 'like a wife' may further imply sexual intercourse."

In 2000, a modern statue of Gilgamesh by the Assyrian sculptor Lewis Batros was unveiled at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)