| INDO - ARYAN MIGRATIONS The Indo-Aryan migrations [note 1] were the migrations into the Indian subcontinent of Indo-Aryan peoples, an ethnolinguistic group that spoke Indo-Aryan languages, the predominant languages of today's North India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Indo-Aryan population movements into the region and Anatolia (ancient Mitanni) from Central Asia are considered to have started after 2000 BCE, as a slow diffusion after the Late Harappan period, which led to a language shift in the northern Indian subcontinent. The Iranian languages were brought into Iran by the Iranians, who were closely related to the Indo-Aryans.

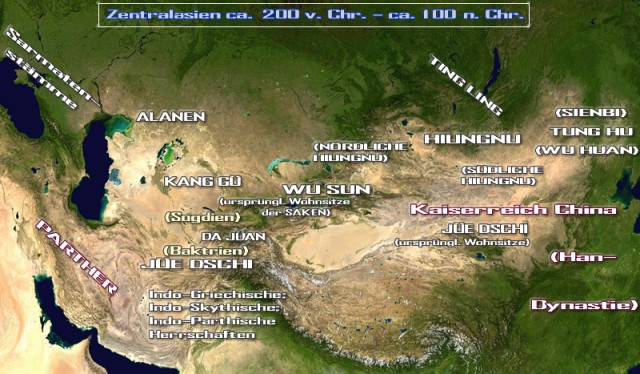

The Proto-Indo-Iranian culture, which gave rise to the Indo-Aryans and Iranians, developed on the Central Asian steppes north of the Caspian Sea as the Sintashta culture (2200 – 1800 BCE) in present-day Russia and Kazakhstan, and developed further as the Andronovo culture (2000–900 BCE), around the Aral Sea. The proto-Indo-Iranians then migrated southwards to the Bactria-Margiana Culture, from which they borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs and practices. The Indo-Aryans split off around 2000 BCE to 1600 BCE from the Iranians, whereafter the Indo-Aryans migrated into Anatolia and, possibly in multiple waves, the Punjab (northern Pakistan and India), while the Iranians moved into Iran, both bringing with them the Indo-Iranian languages.

Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland.

This linguistic argument is supported by archeological, anthropological, genetical, literary and ecological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetic puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. Ecological studies reveal that in the second millennium BCE widespread aridization lead to water shortages and ecological changes in both the Eurasian steppes and the Indian subcontinent, causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations, resulting in the merger of migrating peoples with the post-urban cultures.

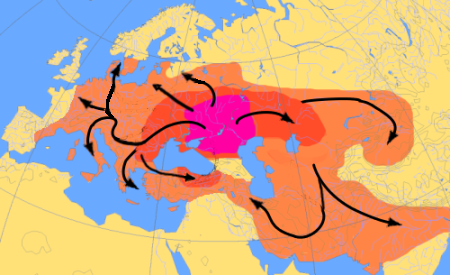

The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 2000 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. It was part of the diffusion of Indo-European languages from the proto-Indo-European homeland at the Pontic–Caspian steppe, a large area of grasslands in far Eastern Europe, which started in the 5th to 4th millennia BCE, and the Indo-European migrations out of the Eurasian Steppes, which started approximately in 2000 BCE.

The theory posits that these Indo-Aryan speaking people were united by shared cultural norms and language, referred to as arya, "noble". Diffusion of this culture and language took place by patron-client systems, which allowed for the absorption and acculturation of other groups into this culture, and explains the strong influence on other cultures with which it interacted.

Fundamentals :

•

Scheme of Indo-European migrations, of which the Indo-Aryan migrations

form a part, from ca. 4000 to 1000 BCE according to the Kurgan hypothesis

:

Linguistics:

relationships between languages :

Archaeology:

migrations from the steppe Urheimat :

A wider "horizon" developed, called the Kurgan culture by Marija Gimbutas in the 1950s. She included several cultures in this "Kurgan Culture", including the Samara culture and the Yamna culture, although the Yamna culture (36th–23rd centuries BCE), also called "Pit Grave Culture", may more aptly be called the "nucleus" of the proto-Indo-European language. From this area, which already included various subcultures, Indo-European languages spread west, south and east starting around 4,000 BCE. These languages may have been carried by small groups of males, with patron-client systems which allowed for the inclusion of other groups into their cultural system.

Eastward emerged the Sintashta culture (2200–1800 BCE), where common Indo-Iranian was spoken. Out of the Shintashta culture developed the Andronovo culture (2000–900 BCE), which interacted with the Bactria-Margiana Culture (2400–1600 BCE). This interaction further shaped the Indo-Iranians, which split at c. 2000–1600 BCE into the Indo-Aryans and the Iranians. The Indo-Aryans migrated to the Levant and South Asia. The migration into northern India was not a large-scale immigration, but may have consisted of small groups [note 2] which were genetically diverse. [clarification needed] Their culture and language spread by the same mechanisms of acculturalisation, and the absorption of other groups into their patron-client system.

Anthropology:

elite recruitment and language shift :

David Anthony, in his "revised Steppe hypothesis" notes that the spread of the Indo-European languages probably did not happen through "chain-type folk migrations", but by the introduction of these languages by ritual and political elites, which were emulated by large groups of people, [note 3] a process which he calls "elite recruitment".

According to Parpola, local elites joined "small but powerful groups" of Indo-European speaking migrants. These migrants had an attractive social system and good weapons, and luxury goods which marked their status and power. Joining these groups was attractive for local leaders, since it strengthened their position, and gave them additional advantages. These new members were further incorporated by matrimonial alliances.

According to Joseph Salmons, language shift is facilitated by "dislocation" of language communities, in which the elite is taken over. According to Salmons, this change is facilitated by "systematic changes in community structure", in which a local community becomes incorporated in a larger social structure. [note 4]

Genetics:

ancient ancestry and multiple gene flows :

Moorjani et al. (2013) describe three scenarios regarding the bringing together of the two groups: migrations before the development of agriculture before 8,000–9,000 years before present (BP); migration of western Asian [note 6] people together with the spread of agriculture, maybe up to 4,600 years BP; migrations of western Eurasians from 3,000 to 4,000 years BP.

While Reich notes that the onset of admixture coincides with the arrival of Indo-European language, according to Moorjani et al. (2013) these groups were present "unmixed" in India before the Indo-Aryan migrations. Gallego Romero et al. (2011) propose that the ANI component came from Iran and the Middle East, less than 10,000 years ago, [note 7] while according to Lazaridis et al. (2016) ANI is a mix of "early farmers of western Iran" and "people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe". Several studies also show traces of later influxes of maternal genetic material [web 4] and of paternal genetic material related to ANI and possibly the Indo-Europeans.

Literary

research: similarities, geography, and references to migration :

Ecological

studies: widespread drought, urban collapse, and pastoral migrations

:

Around 4200–4100 BCE a climate change occurred, manifesting in colder winters in Europe. Steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

The Yamna horizon was an adaptation to a climate change which occurred between 3500 and 3000 BCE, in which the steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved frequently to feed them sufficiently, and the use of wagons and horse-back riding made this possible, leading to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism".

In the second millennium BCE widespread aridification led to water shortages and ecological changes in both the Eurasian steppes and the Indian subcontinent. On the steppes, humidification led to a change of vegetation, triggering "higher mobility and transition to nomadic cattle breeding". [note 8] [note 9] Water shortage [when?] also had a strong impact in the Indian subcontinent, "causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations".

Development

:

In a memoir sent to the French Academy of Sciences in 1767 Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux, a French Jesuit who spent all his life in India, had specifically demonstrated the existing analogy between Sanskrit and European languages. [note 10]

In 1786 William Jones, a judge in the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William, Calcutta, linguist, and classics scholar, on studying Sanskrit, postulated, in his Third Anniversary Discourse to the Asiatic Society, a proto-language uniting Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, Gothic and Celtic languages, but in many ways his work was less accurate than his predecessors', as he erroneously included Egyptian, Japanese and Chinese in the Indo-European languages, while omitting Hindustani and Slavic :

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family, if this were the place for discussing any question concerning the antiquities of Persia.

Jones concluded that all these languages originated from the same source.

Homeland

:

With the 20th-century discovery of Bronze-Age attestations of Indo-European (Anatolian, Mycenaean Greek), Vedic Sanskrit lost its special status as the most archaic Indo-European language known.

Aryan "race" :

A 1910 depiction of Aryans entering India, from Hutchinson's "History of the Nations"

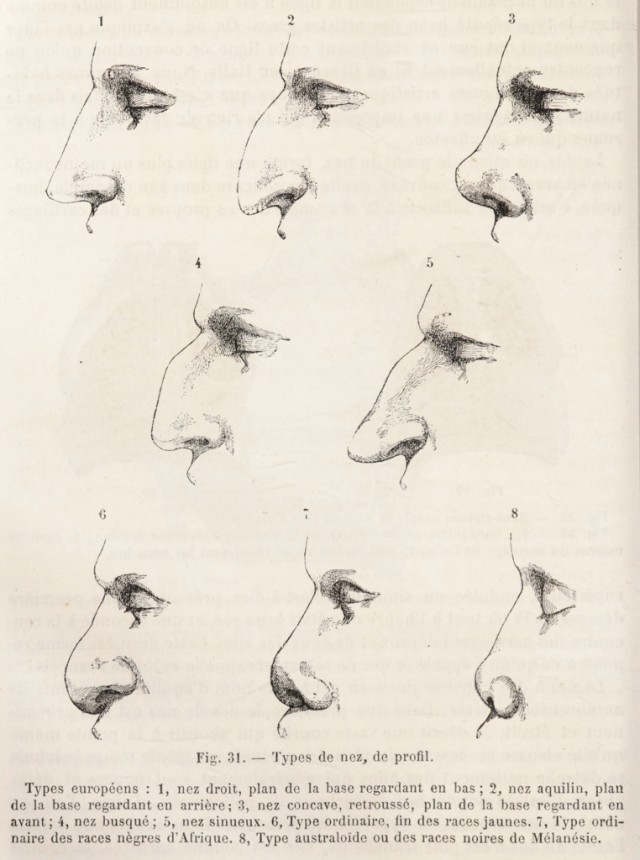

The nasal index: a method of classifying ethnicity based on the

ratio of the breadth of a nose to its height, Developed by Paul

Topinard. "Narrow" noses (Types 1 – 5) indicate

European origin; "medium" noses (Type 6) are the "yellow

races"; and "broad" are either African (Type 7) or

Melanesian and Australian aboriginal (Type 8).

Herbert Hope Risley expanded on Müller's two-race Indo-European speaking Aryan invasion theory, concluding that the caste system was a remnant of the Indo-Aryans domination of the native Dravidians, with observable variations in phenotypes between hereditary, race based, castes. Thomas Trautmann explains that Risley "found a direct relation between the proportion of Aryan blood and the nasal index, along a gradient from the highest castes to the lowest. This assimilation of caste to race proved very influential."

Müller's work contributed to the developing interest in Aryan culture, which often set Indo-European ('Aryan') traditions in opposition to Semitic religions. He was "deeply saddened by the fact that these classifications later came to be expressed in racist terms", as this was far from his intention. [note 11] For Müller the discovery of common Indian and European ancestry was a powerful argument against racism, arguing that "an ethnologist who speaks of Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair, is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar" and that "the blackest Hindus represent an earlier stage of Aryan speech and thought than the fairest Scandinavians". In his later work, Max Müller took great care to limit the use of the term "Aryan" to a strictly linguistic one.

"Aryan

invasion" :

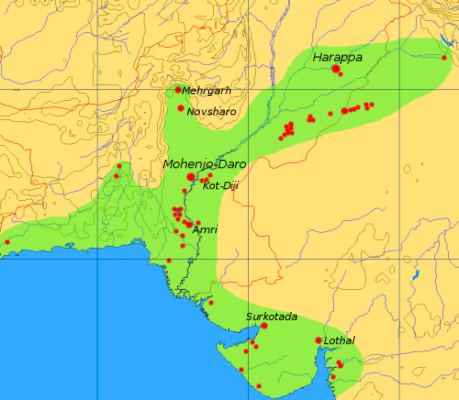

This possibility was for a short time [when?] seen as a hostile invasion into northern India. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation at precisely the period in history in which the Indo-Aryan migrations probably took place, seemed to provide independent support of such an invasion. This argument was proposed by the mid-20th century archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, who interpreted the presence of many unburied corpses found in the top levels of Mohenjo-daro as the victims of conquest wars, and who famously stated that the god "Indra stands accused" of the destruction of the Civilisation.

This position was discarded after finding no evidence of wars. The skeletons were found to be hasty interments, not massacred victims. Wheeler himself also nuanced this interpretation in later publications, stating "This is a possibility, but it can't be proven, and it may not be correct." Wheeler further notes that the unburied corpses may indicate an event in the final phase of human occupation of Mohenjo-Daro, and that thereafter the place was uninhabited, but that the decay of Mohenjo-Daro has to be ascribed to structural causes such as salinisation.

Nevertheless, although 'invasion' was discredited, critics [who?] of the Indo-Aryan Migration theory continue to present the theory as an "Aryan Invasion Theory", [note 12] presenting it as a racist and colonialist discourse :

The theory of an immigration of IA speaking Arya ("Aryan invasion") is simply seen as a means of British policy to justify their own intrusion into India and their subsequent colonial rule: in both cases, a "white race" was seen as subduing the local darker colored population.

Aryan Migration :

An early 20th century depiction of Aryans settling in agricultural villages in India In the later 20th century, ideas were refined along with data accrual, and migration and acculturation were seen as the methods whereby Indo-Aryans and their language and culture spread into northwest India around 1500 BCE. The term "invasion" is only being used nowadays by opponents [who?] of the Indo-Aryan Migration theory. Michael Witzel :

...it has been supplanted by much more sophisticated models over the past few decades [...] philologists first, and archaeologists somewhat later, noticed certain inconsistencies in the older theory and tried to find new explanations, a new version of the immigration theories. [note 13]

The changed approach was in line with newly developed thinking about language transfer in general, such as the migration of the Greeks into Greece (between 2100 and 1600 BCE) and their adoption of a syllabic script, Linear B, from the pre-existing Linear A, with the purpose of writing Mycenaean Greek, or the Indo-Europeanization of Western Europe (in stages between 2200 and 1300 BCE).

Linguistics:

relationships between languages :

Comparative

method :

Linguistics use the comparative method to study the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor, as opposed to the method of internal reconstruction, which analyses the internal development of a single language over time. Ordinarily both methods are used together to reconstruct prehistoric phases of languages, to fill in gaps in the historical record of a language, to discover the development of phonological, morphological, and other linguistic systems, and to confirm or refute hypothesized relationships between languages.

The comparative method aims to prove that two or more historically attested languages are descended from a single proto-language by comparing lists of cognate terms. From them, regular sound correspondences between the languages are established, and a sequence of regular sound changes can then be postulated, which allows the proto-language to be reconstructed. Relation is deemed certain only if at least a partial reconstruction of the common ancestor is feasible, and if regular sound correspondences can be established with chance similarities ruled out.

The comparative method was developed over the 19th century. Key contributions were made by the Danish scholars Rasmus Rask and Karl Verner and the German scholar Jacob Grimm. The first linguist to offer reconstructed forms from a proto-language was August Schleicher, in his Compendium der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, originally published in 1861.

Proto-Indo-European

:

Scholars [who?] estimate that PIE may have been spoken as a single language (before divergence began) around 3500 BCE, though estimates by different [who?] authorities can vary by more than a millennium. A number of hypotheses have been proposed for the origin and spread of the language, the most popular[peacock prose] among linguists being the Kurgan hypothesis, which postulates an origin in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Eastern Europe. Features of the culture of the speakers of PIE, known as Proto-Indo-Europeans, have also been reconstructed based on the shared vocabulary of the early attested Indo-European languages.[citation needed]

As mentioned above, the existence of PIE was first postulated in the 18th century by Sir William Jones, who observed the similarities between Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin. By the early 20th century, well-defined descriptions of PIE had been developed that are still accepted [by whom?] today (with some refinements). The largest developments of the 20th century were the discovery of the Anatolian and Tocharian languages and the acceptance of the laryngeal theory. The Anatolian languages have also spurred a major re-evaluation of theories concerning the development of various shared Indo-European language features and the extent to which these features were present in PIE itself. [citation needed] Relationships to other language families, including the Uralic languages, have been proposed but remain controversial. [citation needed]

PIE is thought [by whom?] to have had a complex system of morphology that included inflectional suffixes as well as ablaut (vowel alterations, as preserved in English sing, sang, sung). Nouns and verbs had complex systems of declension and conjugation respectively.

Arguments

against an Indian origin of proto-Indo-European :

Both mainstream Urheimat solutions locate the Proto-Indo-European homeland in the vicinity of the Black Sea.

Dialectal variation :

This

section may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please

help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without

removing the technical details. (August 2020)

The strong correspondence between the dialectal relationships of the Indo-European languages and their actual geographical arrangement in their earliest attested forms makes an Indian origin, as suggested by the Out of India Theory, unlikely.

Substrate

influence :

Dravidian and other South Asian languages share with Indo-Aryan a number of syntactical and morphological features that are alien to other Indo-European languages, including even its closest relative, Old Iranian. Phonologically, there is the introduction of retroflexes, which alternate with dentals in Indo-Aryan; morphologically there are the gerunds; and syntactically there is the use of a quotative marker (iti). [note 15] These are taken as evidence of substratum influence.

It has been argued [by whom?] that Dravidian influenced Indic through "shift", whereby native Dravidian speakers learned and adopted Indic languages.[citation needed] The presence of Dravidian structural features in Old Indo-Aryan is thus plausibly explained, that the majority of early Old Indo-Aryan speakers had a Dravidian mother tongue which they gradually abandoned. Even though the innovative traits in Indic could be explained by multiple internal explanations, early Dravidian influence is the only explanation that can account for all of the innovations at once – it becomes a question of explanatory parsimony; moreover, early Dravidian influence accounts for several of the innovative traits in Indic better than any internal explanation that has been proposed.

A pre-Indo-European linguistic substratum in the Indian subcontinent would be a good reason to exclude India as a potential Indo-European homeland. However, several linguists [who?], all of whom accept the external origin of the Aryan languages on other grounds, are still open to considering the evidence as internal developments rather than the result of substrate influences, or as adstratum effects.

Archaeology: migrations from the steppe Urheimat :

Stages

of migrations :

Diffusion

from the "Urheimat" :

Theory

of multiple migrations :

The oldest attested Indo-European language is Hittite, which belongs to the oldest written Indo-European languages, the Anatolian branch. Although the Hittites are placed in the 2nd millennium BCE, the Anatolian branch seems to predate Proto-Indo-European, and may have developed from an older Pre-Proto-Indo-European ancestor. If it separated from Proto-Indo-European, it is likely to have done so between 4500 and 3500 BCE.

A migration of archaic Proto-Indo-European speaking steppe herders into the lower Danube valley took place about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

According to Mallory and Adams, migrations southward founded the Maykop culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE), and eastward the Afanasevo culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE), which developed into the Tocharians (c. 3700–3300 BCE).

According to Anthony, between 3100–2800/2600 BCE, a real folk migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture took place toward the west, into the Danube Valley. These migrations probably split off Pre-Italic, Pre-Celtic and Pre-Germanic from Proto-Indo-European. According to Anthony, this was followed by a movement north, which split away Baltic-Slavic c. 2800 BCE. Pre-Armenian split off at the same time. According to Parpola, this migration is related to the appearance of Indo-European speakers from Europe in Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite.

The Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (ca. 2900–2450/2350 cal. BCE), has been associated with some of the languages in the Indo-European family. According to Haak et al. (2015) a massive migration took place from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe.

Yamna culture This migration is closely associated with the Corded Ware culture.

The Indo-Iranian language and culture emerged in the Sintashta culture (c. 2200–1800 BCE), where the chariot was invented. Allentoft et al. (2015) found close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture, which "suggests similar genetic sources of the two", and may imply that "the Sintashta derives directly from an eastward migration of Corded Ware peoples".

The Indo-Iranian language and culture was further developed in the Andronovo culture (c. 2000–900 BCE), and influenced by the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (c. 2400–1600 BCE). The Indo-Aryans split off around 2000–1600 BCE from the Iranians, whereafter Indo-Aryan groups moved to the Levant (Mitanni), northern India (Vedic people, c. 1500 BCE), and China (Wusun). Thereafter the Iranians migrated into Iran.

Central

Asia: formation of Indo-Iranians :

The Proto-Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the Andronovo culture, that flourished ca. 2000–900 BCE in an area of the Eurasian Steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east. The older Sintashta culture (2200–1800), formerly included within the Andronovo culture, is now considered separately, but regarded as its predecessor, and accepted as part of the wider Andronovo horizon.

The Indo-Aryan migration was part of the Indo-Iranian migrations from the Andronovo culture into Anatolia, Iran and South-Asia.

Sintashta-Petrovka culture :

According to Allentoft (2015), the Sintashta culture probably derived from the Corded Ware Culture

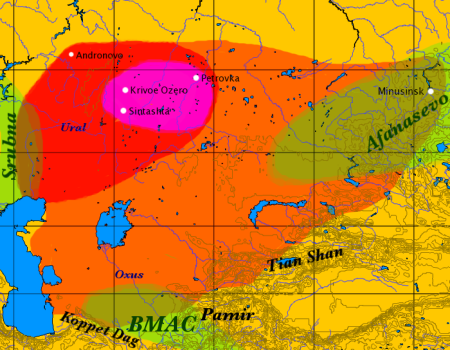

Map

of the approximate maximal extent of the Andronovo culture. The

formative Sintashta-Petrovka culture is shown in darker red. The

location of the earliest spoke-wheeled chariot finds is indicated

in purple. Adjacent and overlapping cultures (Afanasevo, Srubna,

Bactria-Margiana Culture are shown in green.

The Sintashta culture emerged from the interaction of two antecedent cultures. Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BCE. Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltovka settlements or close to Poltovka cemeteries, and Poltovka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery. Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, a collection of Corded Ware settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist. Allentoft et al. (2015) also found close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture.

The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare. Sintashta settlements are also remarkable for the intensity of copper mining and bronze metallurgy carried out there, which is unusual for a steppe culture.

Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only recently distinguished from the Andronovo culture. It is now recognised as a separate entity forming part of the 'Andronovo horizon'.

Andronovo culture :

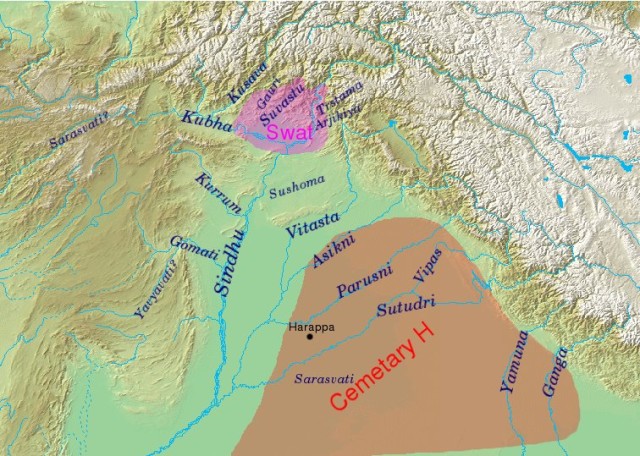

Archaeological cultures associated with Indo-Iranian migrations and Indo-Aryan migrations (after EIEC) The

Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have often been associated with

Indo-Iranian migrations. The GGC, Cemetery H, Copper Hoard and PGW

cultures are candidates for cultures associated with Indo-Aryan

migrations.

The following Andronovo Sub-cultures have been distinguished :

•

Fedorovo (1900–1400 BC) in southern Siberia (earliest evidence

of cremation and fire cult)

Towards the middle of the 2nd millennium, the Andronovo cultures begin to move intensively eastwards. They mined deposits of copper ore in the Altai Mountains and lived in villages of as many as ten sunken log cabin houses measuring up to 30m by 60m in size. Burials were made in stone cists or stone enclosures with buried timber chambers.

In other respects, the economy was pastoral, based on cattle, horses, sheep, and goats. While agricultural use has been posited[by whom?], no clear evidence has been presented.

Studies associate the Andronovo horizon with early Indo-Iranian languages, though it may have overlapped the early Uralic-speaking area at its northern fringe, including the Turkic-speaking area at its northeastern fringe.

Based on its use by Indo-Aryans in Mitanni and Vedic India, its prior absence in the Near East and Harappan India, and its 19–20th century BCE attestation at the Andronovo site of Sintashta, Kuz'mina (1994) argues that the chariot corroborates the identification of Andronovo as Indo-Iranian. [note 17] Anthony & Vinogradov (1995) dated a chariot burial at Krivoye Lake to about 2000 BCE and a Bactria-Margiana burial that also contains a foal has recently been found, indicating further links with the steppes.

Mallory acknowledges the difficulties of making a case for expansions from Andronovo to northern India, and that attempts to link the Indo-Aryans to such sites as the Beshkent and Vakhsh cultures "only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans". He has developed the "kulturkugel" model that has the Indo-Iranians taking over Bactria-Margiana cultural traits but preserving their language and religion [contradictory] while moving into Iran and India. Fred Hiebert also agrees that an expansion of the BMAC into Iran and the margin of the Indus Valley is "the best candidate for an archaeological correlate of the introduction of Indo-Iranian speakers to Iran and South Asia." According to Narasimhan et al. (2018), the expansion of the Andronovo culture towards the BMAC took place via the Inner Asia Mountain Corridor.

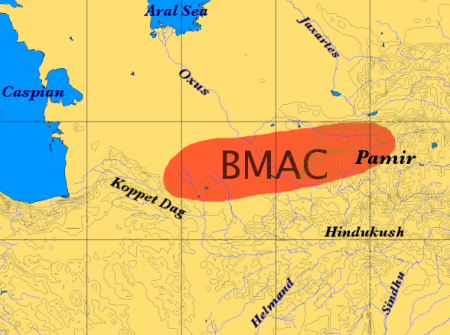

Bactria-Margiana culture :

The Bactria-Margiana Culture, also called "Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex", was a non-Indo-European culture which influenced the Indo-Iranians. It was centered in what is nowadays northwestern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan. Proto-Indo-Iranian arose due to this influence.

The Indo-Iranians also borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs [contradictory] and practices from this culture. According to Anthony, the Old Indic religion probably emerged among Indo-European immigrants in the contact zone between the Zeravshan River (present-day Uzbekistan) and (present-day) Iran. It was "a syncretic mixture of old Central Asian and new Indo-European elements", which borrowed "distinctive religious beliefs and practices" from the Bactria–Margiana Culture. At least 383 non-Indo-European words were borrowed from this culture, including the god Indra and the ritual drink Soma.

The characteristically Bactria-Margiana (southern Turkmenistan/northern Afghanistan) artifacts found at burials in Mehrgarh and Balochistan are explained by a movement of peoples from Central Asia to the south. The Indo-Aryan tribes may have been present in the area of the BMAC from 1700 BCE at the latest (incidentally corresponding with the decline of that culture).

From the BMAC, the Indo-Aryans moved into the Indian subcontinent. According to Bryant, the Bactria-Margiana material inventory of the Mehrgarh and Baluchistan burials is "evidence of an archaeological intrusion into the subcontinent from Central Asia during the commonly accepted time frame for the arrival of the Indo-Aryans". [note 18]

Two

waves of Indo-Iranian migration :

First wave – Indo-Aryan migrations :

Map of the Near East ca. 1400 BCE showing the Kingdom of Mitanni at its greatest extent Mitanni (Hittite cuneiform KURURUMi-ta-an-ni), also Mittani (Mi-it-ta-ni) or Hanigalbat (Assyrian Hanigalbat, Khanigalbat cuneiform ha-ni-gal-bat) or Naharin in ancient Egyptian texts was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and south-east Anatolia from ca. 1600 BCE–1350 BCE.

According to one hypothesis, founded by an Indo-Aryan ruling class governing a predominately Hurrian population, Mitanni came to be a regional power after the Hittite destruction of Amorite Babylon and a series of ineffectual Assyrian kings created a power vacuum in Mesopotamia. At the beginning of its history, Mitanni's major rival was Egypt under the Thutmosids. However, with the ascent of the Hittite empire, Mitanni and Egypt made an alliance to protect their mutual interests from the threat of Hittite domination.

At the height of its power, during the 14th century BCE, Mitanni had outposts centered on its capital, Washukanni, whose location has been determined by archaeologists to be on the headwaters of the Khabur River. Their sphere of influence is shown in Hurrian place names, personal names and the spread through Syria and the Levant of a distinct pottery type. Eventually, Mitanni succumbed to Hittite and later Assyrian attacks, and was reduced to the status of a province of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

The earliest written evidence for an Indo-Aryan language is found not in Northwestern India and Pakistan, but in northern Syria, the location of the Mitanni kingdom. The Mitanni kings took Old Indic throne names, and Old Indic technical terms were used for horse-riding and chariot-driving. The Old Indic term r'ta, meaning "cosmic order and truth", the central concept of the RigVed, was also employed in the Mitanni kingdom. Old Indic gods, including Indra, were also known in the Mitanni kingdom.

North-India

– Vedic culture :

Geography of the RigVed, with river names; the extent of the Swat and Cemetery H cultures are indicated The standard model [by whom?] for the entry of the Indo-European languages into India is that Indo-Aryan migrants went over the Hindu Kush, forming the Gandhar grave culture or Swat culture, in present-day Swat valley, into the headwaters of either the Indus or the Ganges (probably both). The Gandhar grave culture, which emerged c. 1600 BCE, and flourished from c. 1500 BCE to 500 BCE in Gandhar, modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, is thus the most likely locus of the earliest bearers of Rigvedic culture.

Based on this Parpola postulates a first wave of immigration from as early as 1900 BCE, corresponding to the Cemetery H culture, and an immigration to the Punjab ca. 1700–1400 BCE. [note 19]

According to Kochhar there were three waves of Indo-Aryan immigration that occurred after the mature Harappan phase :

1.

The "Murghamu" (Bactria-Margiana Culture) related people

who entered Balochistan at Pirak, Mehrgarh south cemetery, and other

places, and later merged with the post-urban Harappans during the

late Harappans Jhukar phase (2000–1800 BCE);

Spread

of Vedic-Brahmanic culture :

The Central Ganges Plain, where Magadh gained prominence, forming the base of the Maurya Empire, was a distinct cultural area, with new states arising after 500 BCE during the so-called "Second urbanisation". [note 20] It was influenced by the Vedic culture, but differed markedly from the Kuru-Panchala region. It "was the area of the earliest known cultivation of rice in the Indian subcontinent and by 1800 BCE was the location of an advanced neolithic population associated with the sites of Chirand and Chechar". In this region the Shramanic movements flourished, and Jainism and Buddhism originated. [note 21]

Indus

Valley Civilization :

Decline

of Indus Valley Civilisation :

Jim G. Shaffer and Lichtenstein contend that in the second millennium BCE considerable "location processes" took place. In the eastern Punjab 79.9% and in Gujarat 96% of sites changed settlement status. According to Shaffer & Lichtenstein,

It is evident that a major geographic population shift accompanied this 2nd millennium BCE localisation process. This shift by Harappan and, perhaps, other Indus Valley cultural mosaic groups, is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in the Indian subcontinent before the first half of the first millennium B.C.

Continuity

of Indus Valley civilization :

According to Kennedy, there is no evidence of "demographic disruptions" after the decline of the Harappa culture. [note 25] Kenoyer notes that no biological evidence can be found for major new populations in post-Harappan communities. [note 26] Hemphill notes that "patterns of phonetic affinity" between Bactria and the Indus Valley Civilisation are best explained by "a pattern of long-standing, but low-level bidirectional mutual exchange". [note 27]

According to Kennedy, the Cemetery H culture "shows clear biological affinities" with the earlier population of Harappa. The archaeologist Kenoyer noted that this culture "may only reflect a change in the focus of settlement organization from that which was the pattern of the earlier Harappan phase and not cultural discontinuity, urban decay, invading aliens, or site abandonment, all of which have been suggested in the past." Recent excavations in 2008 at Alamgirpur, Meerut District, appeared to show an overlap between the Harappan and PGW [expand acronym] pottery indicating cultural continuity.

Relation

with Indo-Aryan migrations :

Evidence in material culture for systems collapse, abandonment of old beliefs and large-scale, if localised, population shifts in response to ecological catastrophe in the 2nd millennium B.C. must all now be related to the spread of Indo-Aryan languages.

Erdosy, testing hypotheses derived from linguistic evidence against hypotheses derived from archaeological data, states that there is no evidence of "invasions by a barbaric race enjoying technological and military superiority", but "some support was found in the archaeological record for small-scale migrations from Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent in the late 3rd/early 2nd millennia BCE". According to Erdosy, the postulated movements within Central Asia can be placed within a processional framework, replacing simplistic concepts of "diffusion", "migrations" and "invasions".

Scholars have argued that the historical Vedic culture is the result of an amalgamation of the immigrating Indo-Aryans with the remnants of the indigenous civilization, such as the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. Such remnants of IVC [expand acronym] culture are not prominent in the RigVed, with its focus on chariot warfare and nomadic pastoralism in stark contrast with an urban civilization.

Inner

Asia – Wusun and Yuezhi :

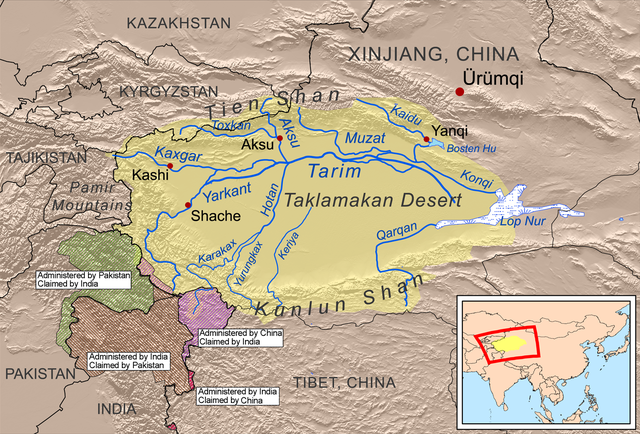

The Tarim Basin, 2008

Wusun and their neighbours during the late 2nd century BCE, take note that the Yancai did not change their name to Alans until the 1st century

The migrations of the Yuezhi through Central Asia, from around 176 BCE to 30 CE According to Christopher I. Beckwith the Wusun, an Indo-European Caucasian people of Inner Asia in antiquity, were also of Indo-Aryan origin. From the Chinese term Wusun, Beckwith reconstructs the Old Chinese *âswin, which he compares to the Old Indic asvin "the horsemen", the name of the Rigvedic twin equestrian gods. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun were an eastern remnant of the Indo-Aryans, who had been suddenly pushed to the extremeties of the Eurasian Steppe by the Iranian peoples in the 2nd millennium BCE.

The Wusun are first mentioned [when?] by Chinese sources as vassals in the Tarim Basin of the Yuezhi, another Indo-European Caucasian people of possible Tocharian stock. Around 175 BCE, the Yuezhi were utterly defeated by the Xiongnu, also former vassals of the Yuezhi. The Yuezhi subsequently attacked the Wusun and killed their king Nandoumi, capturing the Ili Valley from the Saka (Scythians) shortly afterwards. In return the Wusun settled in the former territories of the Yuezhi as vassals of the Xiongnu.

The son of Nandoumi was adopted by the Xiongnu king and made leader of the Wusun. Around 130 BCE he attacked and utterly defeated the Yuezhi, settling the Wusun in the Ili Valley. After the Yuezhi were defeated by the Xiongnu, in the 2nd century BCE, a small group, known as the Little Yuezhi, fled to the south, while the majority migrated west to the Ili Valley, where they displaced the Sakas (Scythians). Driven from the Ili Valley shortly afterwards by the Wusun, the Yuezhi migrated to Sogdia and then Bactria, where they are often identified with the Tókharoi and Asii of Classical sources. They then expanded into northern Indian subcontinent, where one branch of the Yuezhi founded the Kushan Empire. The Kushan empire stretched from Turpan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Indo-Gangetic Plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China.

Soon after 130 BCE the Wusun became independent of the Xiongnu, becoming trusted vassals of the Han dynasty and powerful force in the region for centuries. With the emerging steppe federations of the Rouran, the Wusun migrated into the Pamir Mountains in the 5th century CE. They are last mentioned in 938 when a Wusun chieftain paid tribute to the Liao dynasty.

Second wave – Iranians :

The first Iranians to reach the Black Sea may have been the Cimmerians in the 8th century BCE, although their linguistic affiliation is uncertain. They were followed by the Scythians [when?], whom would dominate the area, at their height, from the Carpathian Mountains in the west, to the easternmost fringes of Central Asia in the east. For most of their [who?] existence, they were based in what is modern-day Ukraine and southern European Russia. Sarmatian tribes, of whom the best known are the Roxolani (Rhoxolani), Iazyges (Jazyges) and the Alans, followed the Scythians westwards into Europe in the late centuries BCE and the 1st and 2nd centuries of the Common Era (The Migration Period). The populous Sarmatian tribe of the Massagetae, dwelling near the Caspian Sea, were known to the early rulers of Persia in the Achaemenid Period. In the east, the Scythians occupied several areas in Xinjiang, from Khotan to Tumshuq.

The Medes, Parthians and Persians begin to appear on the western Iranian Plateau from c. 800 BCE, after which they remained under Assyrian rule for several centuries, as it was with the rest of the peoples in the Near East. The Achaemenids replaced Median rule from 559 BCE. Around the first millennium of the Common Era (AD), the Kambojas, the Pashtuns and the Baloch began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian Plateau, on the mountainous frontier of northwestern and western Pakistan, displacing the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

In Central Asia, the Turkic languages have marginalized Iranian languages as a result of the Turkic migration of the early centuries CE. In Eastern Europe, Slavic and Germanic peoples assimilated and absorbed the native Iranian languages (Scythian and Sarmatian) of the region. Extant major Iranian languages are Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and Balochi, besides numerous smaller ones.

Anthropology:

elite recruitment and language change :

Renfrew:

models of "linguistic replacement" :

1.

The demographic-subsistence model, exemplified by the process of

agricultural dispersal, in which the incoming group has exploitive

technologies which makes them dominant. It may lead to significant

gene flow, and significant genetic changes in the population. But

it may also lead to acculturalisation, in which case the technologies

are taken over, but there is less change in the genetic composition

of the population;

Michael

Witzel: small groups and acculturation :

Witzel notes that "arya/arya does not mean a particular 'people' or even a particular 'racial' group but all those who had joined the tribes speaking Vedic Sanskrit and adhering to their cultural norms (such as ritual, poetry, etc.)." According to Witzel, "there must have been a long period of acculturation between the local population and the 'original' immigrants speaking Indo-Aryan." Witzel also notes that the speakers of Indo-Aryan and the local population must have been bilingual, speaking each other's languages and interacting with each other, before the Rg Ved was composed in the Punjab.

Salmons:

systematic changes in community structure :

... understands shift in terms of geographical, social, and cultural "dislocation" of language communities. Social dislocation, to give the most relevant example, involves "siphoning off the talented, the enterprising, the imaginative and the creative" ([Fishman] 1991: 61), and sounds strikingly like Anthony's 'recruitment' scenario.

Salmons himself argues that

... systematic changes in community structure are what drive language shift, incorporating Milroy's network structures as well. The heart of the view is the quintessential element of modernization, namely a shift from local community-internal organization to regional (state or national or international, in modern settings), extra-community organizations. Shift correlates with this move from pre-dominantly "horizontal" community structures to more "vertical" ones. [note 4]

Genetics:

ancient ancestry and multiple gene flows :

Ancestral

groups :

Kivisild et al. (1999) concluded that there is "an extensive deep late Pleistocene [jargon] genetic link between contemporary Europeans and Indians" via the mitochondrial DNA, that is, DNA which is inherited from the mother. According to them, the two groups split at the time of the peopling of Asia and Eurasia and before modern humans entered Europe. Kivisild et al. (2000) note that "the sum of any recent (the last 15,000 years) western mtDNA gene flow to India comprises, in average, less than 10 percent of the contemporary Indian mtDNA lineages."

Kivisild et al. (2003) and Sharma (2005) note that north and south Indians share a common maternal ancestry: Kivisild et al. (2003) further note that "these results show that Indian tribal and caste populations derive largely from the same genetic heritage of Pleistocene [jargon] southern and western Asians and have received limited gene flow from external regions since the Holocene. [jargon]

"Ancestral

North Indians" and "Ancestral South Indians" :

The two groups mixed between 1,900 and 4,200 years ago (2200 BCE – 100 CE) [contradictory], where-after a shift to endogamy took place and admixture became rare. [note 37] Speaking to Fountain Ink, David Reich stated, "Prior to 4,200 years ago, there were unmixed groups in India. Sometime between 1,900 to 4,200 years ago, profound, pervasive convulsive mixture occurred, affecting every Indo-European and Dravidian group in India without exception." Reich pointed out that their work does not show that a substantial migration occurred during this time.

Metspalu et al. (2011), representing a collaboration between the Estonian Biocenter and CCMB, confirmed that the Indian populations are characterized by two major ancestry components. One of them is spread at comparable frequency and haplotype diversity in populations of South and West Asia and the Caucasus. The second component is more restricted to South Asia and accounts for more than 50% of the ancestry in Indian populations. Haplotype diversity associated with these South Asian ancestry components is significantly higher than that of the components dominating the West Eurasian ancestry palette.

Additional

components :

They conclude that, while there may have been an ancient settlement in the subcontinent, "male-dominated genetic elements shaped the Indian gene pool", and that these elements "have earlier been correlated to various languages", and further note "the fluidity of female gene pools when in a patriarchal and patrilocal society, such as that of India".

Basu et al. (2016) extend the study of Reich et al. (2009) by postulating two other populations in addition to the ANI and ASI: "Ancestral Austro-Asiatic" (AAA) and "Ancestral Tibeto-Burman" (ATB), corresponding to the Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman language speakers. According to them, ancestral populations seem to have occupied geographically separated habitats. The ASI and the AAA were early [when?] settlers, who possibly arrived via the southern wave out of Africa. The ANI are related to Central South Asians and entered India through the northwest, while the ATB are related to East Asians and entered India through northeast corridors. They further note that The asymmetry of admixture, with ANI populations providing genomic inputs to tribal populations (AA, Dravidian tribe, and TB) but not vice versa, is consistent with elite dominance and patriarchy. Males from dominant populations, possibly upper castes, with high ANI component, mated outside of their caste, but their offspring were not allowed to be inducted into the caste. This phenomenon has been previously observed as asymmetry in homogeneity of mtDNA and heterogeneity of Y-chromosomal haplotypes in tribal populations of India as well as the African Americans in United States.

Male-mediated

migration :

ArunKumar et al. (2015) "suggest that ancient male-mediated migratory events and settlement in various regional niches led to the present day scenario and peopling of India."

North-south

cline :

Scenarios

:

1.

"migrations that occurred prior to the development of agriculture

[8,000–9,000 years before present (BP)]. Evidence for this

comes from mitochondrial DNA studies, which have shown that the

mitochondrial haplogroups (hg U2, U7, and W) that are most closely

shared between Indians and West Eurasians diverged about 30,000–40,000

years BP."

Narasimhan et al. (2019) conclude that ANI and ASI were formed in the 2nd millennium BCE. They were preceded by IVC-people, a mixture of AASI (ancient ancestral south Indians, that is, hunter-gatherers related), and people related to but distinct from Iranian agri-culturalists, lacking the Anatolian farmer-related ancestry which was common in Iranian farmers after 6000 BCE. [note 43] Those Iranian farmers-related people may have arrived in India before the advent of farming in northern India, and mixed with people related to Indian hunter-gatherers ca. 5400 to 3700 BCE, before the advent of the mature IVC. [note 44] This mixed IVC-population, which probably was native to the Indus Valley Civilisation, "contributed in large proportions to both the ANI and ASI", which took shape during the 2nd millennium BCE. ANI formed out of a mixture of "Indus_Periphery-related groups" and migrants from the steppe, while ASI was formed out of "Indus_Periphery-related groups" who moved south and mixed with hunter-gatherers.

Agricultural

migrations :

Late Harappan phase (1900–1300 BCE)

Early Vedic Culture (1700–1100 BCE) Kivisild et al. (1999) note that "a small fraction of the 'Caucasoid-specific' mtDNA lineages found in Indian populations can be ascribed to a relatively recent admixture." at ca. 9,300 ± 3,000 years before present, which coincides with "the arrival to India of cereals domesticated in the fertile Crescent" and "lends credence to the suggested linguistic connection between Elamite and Dravidic populations". [note 7]

According to Gallego Romero et al. (2011), their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that "the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East." Gallego Romero notes that Indians who are lactose-tolerant show a genetic pattern regarding this tolerance which is "characteristic of the common European mutation". According to Gallego Romero, this suggests that "the most common lactose tolerance mutation made a two-way migration out of the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. While the mutation spread across Europe, another explorer must have brought the mutation eastward to India – likely traveling along the coast of the Persian Gulf where other pockets of the same mutation have been found." In contrast, Allentoft et al. (2015) found that lactose-tolerance was absent in the Yamnaya culture, noting that while "the Yamnaya and these other Bronze Age cultures herded cattle, goats, and sheep, they couldn't digest raw milk as adults. Lactose tolerance was still rare among Europeans and Asians at the end of the Bronze Age, just 2000 years ago."

According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), "farmers related to those from Iran spread northward into the Eurasian steppe; and people related to both the early farmers of Iran and to the pastoralists of the Eurasian steppe spread eastward into South Asia." They further note that ANI "can be modelled as a mix of ancestry related to both early farmers of western Iran and to people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe". [note 45]

Haplogroup R1a and related haplogroups :

R1a origins (Underhill 2010; R1a migration to Eastern Europe; R1a1a diversification (Pamjav 2012); and R1a1a oldest expansion and highest frequency (Underhill 2014) The distribution and proposed origin of haplogroup R1a, more specifically R1a1a1b, is often being used as an argument pro or contra the Indo-Aryan migrations. It is found in high frequencies in Eastern Europe (Z282) and south Asia (Z93), the areas of the Indo-European migrations. The place of origin of this haplogroup may give an indication of the "homeland" of the Indo-Europeans, and the direction of the first migrations.

Cordeaux et al. (2004), based on the spread of a cluster of haplogroups (J2, R1a, R2, and L) in India, with higher rates in northern India, argue that agriculture in south India spread with migrating agriculturalists, which also influenced the genepool in south India.

Sahoo et al. (2006), in response to Cordeaux et al. (2004), suggest that those haplogroups originated in India, based on the spread of these various haplogroups in India. According to Sahoo et al. (2006), this spread "argue[s] against any major influx, from regions north and west of India, of people associated either with the development of agriculture or the spread of the Indo-Aryan language family". They further propose that "the high incidence of R1* and R1a throughout Central Asian and East European populations (without R2 and R* in most cases) is more parsimoniously explained by gene flow in the opposite direction", which according to Sahoo et al. (2006) explains the "sharing of some Y-chromosomal haplogroups between Indian and Central Asian populations".

Sengupta et al. (2006) also comment on Cordeaux et al. (2004), stating that "the influence of Central Asia on the pre-existing gene pool was minor", and arguing for "a peninsular origin of Dravidian speakers than a source with proximity to the Indus and with significant genetic input resulting from demic diffusion associated with agriculture".

Sharma et al. (2009) found a high frequency of R1a1 in India. They therefore argue for an Indian origin of R1a1, and dispute "the origin of Indian higher most castes from Central Asian and Eurasian regions, supporting their origin within the Indian subcontinent".

Underhill et al. (2014/2015) conclude that R1a1a1, the most frequent subclade of R1a, split into Z282 (Europe) and Z93 (Asia) at circe 5,800 before present. According to Underhill et al. (2014/2015), "[t]his suggests the possibility that R1a lineages accompanied demic expansions initiated during the Copper, Bronze, and Iron ages." They further note that the diversification of Z93 and the "early urbanization within the Indus Valley also occurred at this time and the geographic distribution of R1a-M780 (Figure 3d) may reflect this".

Palanichamy et al. (2015), while responding to Cordeaux et al. (2004), Sahoo et al. (2006) and Sengupta et al. (2006), elaborated on Kivisild et al.'s (1999) suggestion that West Eurasian haplogroups "may have been spread by the early Neolithic migrations of proto-Dravidian farmers spreading from the eastern horn of the Fertile Crescent into India". They conclude that "the L1a lineage arrived from western Asia during the Neolithic period and perhaps was associated with the spread of the Dravidian language to India", indicating that "the Dravidian language originated outside India and may have been introduced by pastoralists coming from western Asia (Iran)." They further conclude that two subhalogroups originated with the Dravidian speaking peoples, and may have come to South India when the Dravidian language spread.

Poznik et al. (2016) note that "striking expansions" occurred within R1a-Z93 at ~4,500–4,000 years ago, which "predates by a few centuries the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation". Mascarenhas et al. (2015) note that the expansion of Z93 from Transcaucasia into South Asia is compatible with "the archeological records of eastward expansion of West Asian populations in the 4th millennium BCE culminating in the so-called Kura-Araxes migrations in the post-Uruk IV period".

Indo-European

migrations :

Zerjal et al. (2002) argue that "multiple recent events" may have reshaped "this genetic landscape".

Bamshad et al. (2001), Wells et al. (2002) and Basu et al. (2003) argue for an influx of Indo-European migrants into the Indian subcontinent, but not necessarily an "invasion of any kind". Bamshad et al. (2001) notice that the correlation between caste-status and West Eurasian DNA may be explained by subsequent male immigration into the Indian subcontinent.Basu et al. (2003) argue that the Indian subcontinent was subjected to a series of Indo-European migrations about 1500 BCE.

Metspalu et al. (2011) note that "any nonmarginal migration from Central Asia to South Asia should have also introduced readily apparent signals of East Asian ancestry into India" (although this presupposes the unproven assumption that East Asian ancestry was present – to a significant extent – in prehistorical Central Asia), which is not the case, and conclude that if there was a major migration of Eurasians into India, this happened before the rise of the Yamna culture. Based on Metspalu (2011), Lalji Singh, a co-author of Metspalu, concludes that "[t]here is no genetic evidence that Indo-Aryans invaded or migrated to India".

Moorjani et al. (2013) notes that the period of 4,200–1,900 years BP was a time of dramatic changes in northern India, and coincides with the "likely first appearance of Indo-European languages and Vedic religion in the subcontinent". [note 47] Moorjani further notes that there must have been multiple waves of admixture, which had more impact on higher-caste and northern Indians and took place more recently. [note 48] This may be explained by "additional gene flow", related to the spread of languages :

...at least some of the history of population mixture in India is related to the spread of languages in the subcontinent. One possible explanation for the generally younger dates in northern Indians is that after an original mixture event of ANI and ASI that contributed to all present-day Indians, some northern groups received additional gene flow from groups with high proportions of West Eurasian ancestry, bringing down their average mixture date. [note 49]

Palanichamy et al. (2015), elaborating on Kivisild et al. (1999) conclude that "A large proportion of the west Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups observed among the higher-ranked caste groups, their phylogenetic affinity and age estimate indicate recent Indo-Aryan migration to India from west Asia. According to Palanichamy et al. (2015), "the west Eurasian admixture was restricted to caste rank. It is likely that Indo-Aryan migration has influenced the social stratification in the pre-existing populations and helped in building the Hindu caste system, but it should not be inferred that the contemporary Indian caste groups have directly descended from Indo-Aryan immigrants. [note 50]

Jones et al. (2015) state that CHG [note 51] was "a major contributor to the Ancestral North Indian component". According to Jones et al. (2015), it "may be linked with the spread of Indo-European languages", but they also note that "earlier movements associated with other developments such as that of cereal farming and herding are also plausible".

Basu et al. (2016) note that the ANI are inseparable from Central-South Asian populations in present-day Pakistan. They hypothesise that "the root of ANI is in Central Asia".

According to Lazaridis et al. (2016) ANI "can be modelled as a mix of ancestry related to both early farmers of western Iran and to people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe".

Silva et al. (2017) state that "the recently refined Y-chromosome tree strongly suggests that R1a is indeed a highly plausible marker for the long-contested Bronze Age spread of Indo-Aryan speakers into South Asia." [note 52] Silva et al. (2017) further notes "they likely spread from a single Central Asian source pool, there do seem to be at least three and probably more R1a founder clades within the Subcontinent, consistent with multiple waves of arrival."

Narasimhan et al. (2018) conclude that pastoralists spread southwards from the Eurasian steppe during the period 2300–1500 BCE. These pastoralists, during the 2nd millennium BCE, presumably mixed with the descendants of the Indus Valley Civilisation, who in turn were a mix of Iranian agriculturalists and South Asian hunter-gatherers forming "the single most important source of ancestry in South Asia."

Origins

of R1a-Z93 :

A 2014 study by Peter A. Underhill et al., using 16,244 individuals from over 126 populations from across Eurasia, concluded that there was compelling evidence that "the initial episodes of haplogroup R1a diversification likely occurred in the vicinity of present-day Iran."

Literary

research: similarities, geography, and references to migration :

Brentjes argues that there is not a single cultural element of central Asian, Eastern European, or Caucasian origin in the Mitannian area; he also associates with an Indo-Aryan presence the peacock motif found in the Middle East from before 1600 BCE and quite likely from before 2100 BCE.

Scholars reject the possibility that the Indo-Aryans of Mitanni came from the Indian subcontinent as well as the possibility that the Indo-Aryans of the Indian subcontinent came from the territory of Mitanni, leaving migration from the north the only likely scenario. [note 53] The presence of some Bactria-Margiana loan words in Mitanni, Old Iranian and Vedic further strengthens this scenario. [contradictory]

Iranian

Avesta :

Linguists such as Burrow argue that the strong similarity between the Avestan of the Gathas—the oldest part of the Avesta—and the Vedic Sanskrit of the RigVed pushes the dating of Zarathustra or at least the Gathas closer to the conventional RigVed dating of 1500–1200 BCE, i.e. 1100 BCE, possibly earlier. Boyce concurs with a lower date of 1100 BCE and tentatively proposes an upper date of 1500 BCE. Gnoli dates the Gathas to around 1000 BCE, as does Mallory (1989), with the caveat of a 400-year leeway on either side, i.e. between 1400 and 600 BCE. Therefore, the date of the Avesta could also indicate the date of the RigVed.

There is mention in the Avesta of Airyan Vaejah, one of the '16 the lands of the Aryans'. Gnoli's interpretation of geographic references in the Avesta situates the Airyanem Vaejah in the Hindu Kush. For similar reasons, Boyce excludes places north of the Syr Darya and western Iranian places. With some reservations, Skjaervo concurs that the evidence of the Avestan texts makes it impossible to avoid the conclusion that they were composed somewhere in northeastern Iran. Witzel points to the central Afghan highlands. Humbach derives Vaejah from cognates of the Vedic root "vij", suggesting the region of fast-flowing rivers. Gnoli considers Choresmia (Xvairizem), the lower Oxus region, south of the Aral Sea to be an outlying area in the Avestan world. However, according to Mallory & Mair (2000), the probable homeland of Avestan is, in fact, the area south of the Aral Sea.

Geographical location of Rigvedic rivers :

Cluster of Indus Valley Civilization site along the course of the Indus River in Pakistan. See this for a more detailed map The geography of the RigVed seems to be centered on the land of the seven rivers. While the geography of the Rigvedic rivers is unclear in some of the early books of the RigVed, the Nadistuti sukta is an important source for the geography of late Rigvedic society.

The Sarasvati River is one of the chief Rigvedic rivers. The Nadistuti sukta in the RigVed mentions the Sarasvati between the Yamuna in the east and the Sutlej in the west, and later texts like the Brahmans and Mahabharat mention that the Sarasvati dried up in a desert.

Scholars agree that at least some of the references to the Sarasvati in the RigVed refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River, while the Afghan river Haraxvaiti/Harauvati Helmand is sometimes quoted as the locus of the early Rigvedic river. Whether such a transfer of the name has taken place from the Helmand to the Ghaggar-Hakra is a matter of dispute. Identification of the early Rigvedic Sarasvati with the Ghaggar-Hakra before its assumed drying up early in the second millennium would place the RigVed BCE, well outside the range commonly assumed by Indo-Aryan migration theory.

A non-Indo-Aryan substratum in the river-names and place-names of the Rigvedic homeland would support an external origin of the Indo-Aryans. [citation needed] However, most place-names in the RigVed and the vast majority of the river-names in the north-west of the Indian subcontinent are Indo-Aryan. Non-Indo-Aryan names are, however, frequent in the Ghaggar and Kabul River areas, the first being a post-Harappan stronghold of Indus populations. [citation needed]

Textual

references to migrations :

Probable geographic expansion of late Vedic culture Just as the Avesta does not mention an external homeland of the Zoroastrians, the RigVed does not explicitly refer to an external homeland or to a migration. [note 54] Later Hindu texts, such as the Brahmans, Mahabharat, Ramayan, and Purans, are centered in the Ganges region (rather than Haryana and Punjab) and mention regions still further to the south and east, suggesting a later movement or expansion of the Vedic religion and culture to the east. There is no clear indication of general movement in either direction in the RigVed itself; searching for indirect references in the text, or by correlating geographic references with the proposed order of composition of its hymns, has not led to any consensus on the issue. [citation needed]

Srauta

Sutra of Baudhayan :

Later

Vedic and Hindu texts :

Later Vedic texts show a shift [citation needed] of location from the Punjab to the East. According to the Yajur Ved, Yajnavalkya (a Vedic ritualist and philosopher) lived in the eastern region of Mithila. Aitareya Brahman 33.6.1. records that Vishvamitra's sons migrated to the north, and in Shatpath Brahman 1:2:4:10 the Asurs were driven to the north. In much later texts, Manu was said to be a king from Dravid. In the legend of the flood he stranded with his ship in Northwestern India or the Himalayas. The Vedic lands (e.g. Aryavart, Brahmavart) are located in Northern India or at the Sarasvati and Drishadvati river. However, in a post-Vedic text the Mahabharat Udyog Parv (108), the East is described as the homeland of the Vedic culture, where "the divine Creator of the universe first sang the Veds". The legends of Ikshvaku, Sumati and other Hindu legends may have their origin in Southeast Asia.

The Purans record that Yayati left Prayag (confluence of the Ganges & Yamuna) and conquered the region of Sapta Sindhu. His five sons Yadu, Druhyus, Puru, Anu and Turvashu correspond to the main tribes of the RigVed.

The Puranas also record that the Druhyus were driven out of the land of the seven rivers by Mandhatr and that their next king Gandhar settled in a north-western region which became known as Gandhar. The sons of the later Druhyu king Prachetas are supposed by some to have 'migrated' to the region north of Afghanistan though the Puranic texts only speak of an "adjacent" settlement.

Multiple

waves of migration :

Ecology

:

Around 4200–4100 BCE a climate change occurred, manifesting in colder winters in Europe. Between 4200 and 3900 BCE many tell settlements in the lower Danube Valley were burned and abandoned, while the Cucuteni-Tripolye culture showed an increase in fortifications, meanwhile moving eastwards towards the Dniepr. Steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.

The Yamna horizon was an adaptation to a climate change which occurred between 3500 and 3000 BCE, in which the steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved frequently to feed them sufficiently, and the use of wagons and horse-back riding made this possible, leading to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism". It was accompanied by new social rules and institutions, to regulate the local migrations in the steppes, creating a new social awareness of a distinct culture, and of "cultural Others" who did not participate in these new institutions.

In the second century BCE widespread aridization lead to water shortages and ecological changes in both the Eurasian steppes and south Asia. At the steppes, humidization lead a change of vegetation, triggering "higher mobility and transition to the nomadic cattle breeding". [note 55] [note 56] Water shortage also had a strong impact in south Asia :

This time was one of great upheaval for ecological reasons. Prolonged failure of rains caused acute water shortage in a large area, causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south-central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations. Inevitably, the new arrivals came to merge with and dominate the post-urban cultures.

The Indus Valley Civilisation was localised, that is, urban centers disappeared and were replaced by local cultures, due to a climatic change that is also signalled for the neighbouring areas of the Middle East. As of 2016 many scholars believe that drought and a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia caused the collapse of the Indus Civilisation. The Ghaggar-Hakra system was rain-fed, and water-supply depended on the monsoons. The Indus valley climate grew significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE, linked to a general weakening of the monsoon at that time. The Indian monsoon declined and aridity increased, with the Ghaggar-Hakra retracting its reach towards the foothills of the Himalaya, leading to erratic and less extensive floods that made inundation agriculture less sustainable. Aridification reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward.

Indian

views :

Ancientness of Vedic culture and religion :

The

approximate extent of Aryavart during the late Vedic period (ca.

1100–500 BCE). Aryavart was limited to northwest India and

the western Ganges plain, while Greater Magadh in the east was habitated

by non-Vedic Indo-Aryans, who gave rise to Jainism and Buddhism.

Indigenous

Aryans :

The proposed "Indigenous Aryans" scenario is based on specific interpretations of archaeological, genetic, and linguistic data and on literary interpretations of the RigVed. Standard arguments supporting the "Indigenous Aryans" theory or opposing Indo-Aryan migration theory include the following :

Questioning

the Indo-Aryan migration theory :

Hindu

nationalism :

Undoubtedly ... we Hindus have been in undisputed and undisturbed possession of this land for over 8 or even 10 thousand years before the land was invaded by any foreign race. (Golwakar [1939] 1944) [note 62] [note 63] [note 21]

Racism

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.png)

_and_R1a1a_oldest_expansion_and_highest_frequency_(2014).jpg)

.jpg)