ARCHAEOLOGY

PART - 2

Archaeological

evidence for OIT, Part I -- Jaydeepsinh Rathod November 11, 2019

By Jaydeepsinh_Rathod- 46 Comments On

The Archaeological Evidence for OIT – I

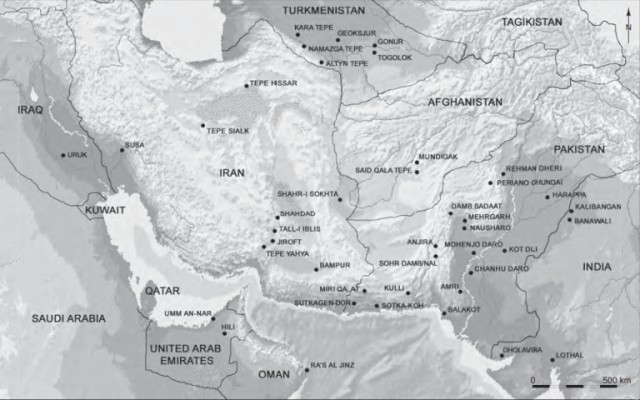

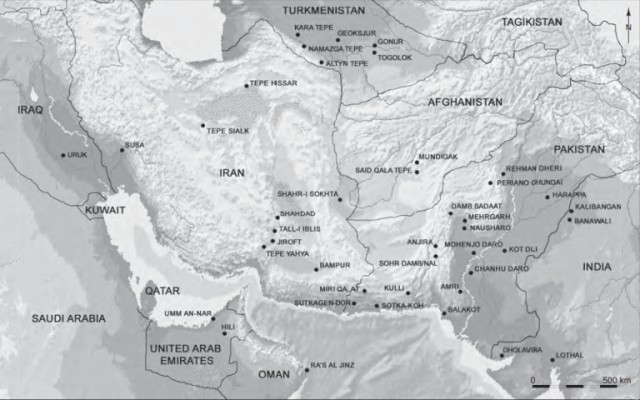

The Chalcolithic & Bronze Age civilizations geographically closest

to the Harappan or the Saraswati-Sindhu civilization were the twin

Eastern Iranian civilizations of Helmand and Halil Rud/Jiroft and

the Central Asian civilization of BMAC (Bactria–Margiana Archaeological

Complex) spread over the southern margins of Turkmenistan &

Uzbekistan and as far east as Tajikistan.

We have discussed the genetic evidence which showed profound Harappan

influence in Helmand and BMAC while the aDNA from Halil Rud civilization,

situated in the Kerman province of modern Iran, further west of

Shahr-i-Sokhta, remains to be sequenced and published.

After having had a look at the genetic data that supports an Out

of India migration into these adjacent regions of Eastern Iran &

Central Asia, it would be in the fitness of things to also have

a brief encounter with the archaeological evidence that can prop

up the above said genetic evidence.

The archaeological data is much varied and quite interesting. However

there is a lot more to learn and perhaps we have so far just scratched

the surface.

Helmand

and Halil Rud :

The twin civilizations of Helmand

and Halil Rud, situated to the west of the Harappan civilization,

were not known until a few decades ago and even today we know very

little about them. In many ways, we know even less about them than

what we know about the Harappan civilization itself.

From what we know it is fairly clear that both of these Eastern

Iranian civilizations preceded by several centuries the BMAC civilization

and were roughly contemporaneous with the Harappan civilization.

All of these southern civilizations, including the Harappan, are

in turn considered to have played a defining role in the formation

of the BMAC, a proposition which has been confirmed by ancient DNA

evidence.

Both the Helmand civilization and its western neighbour, the Halil

Rud civilization were intimately in contact with their geographically

massive eastern neighbouring civilization of the Harappans.

In order to avoid an unduly long post, I shall limit myself over

here to the very intriguing linkages of Harappans with the Helmand

civilization only.

Helmand

and Harappan :

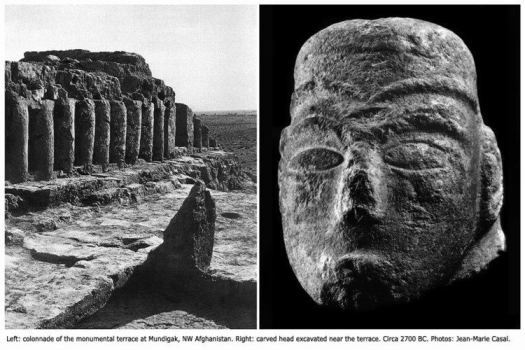

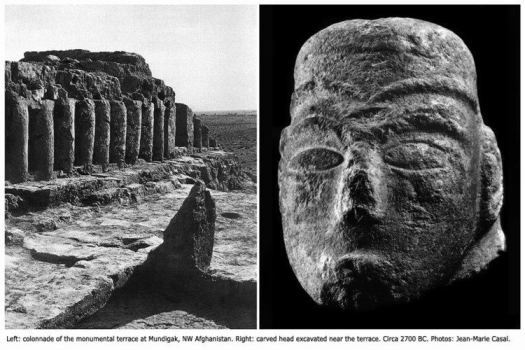

Mundigak, Afghanistan

Burnt

Building, Shahr-i-Sokhta

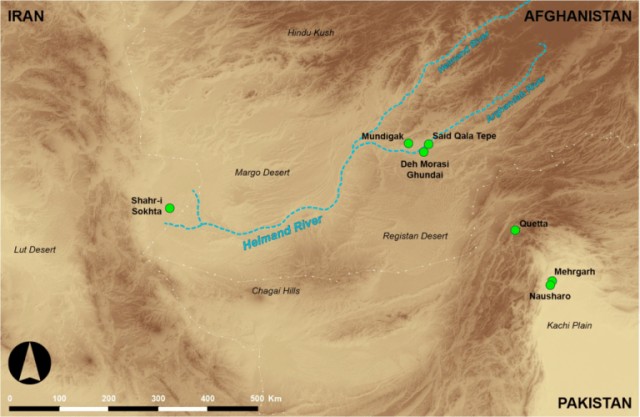

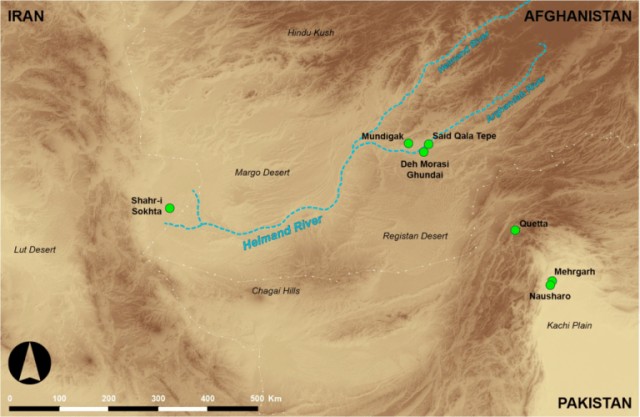

The Helmand civilization centred on the river Helmand which flows

from Afghanistan into Sistan province of Eastern Iran. We know atleast

two of its major sites – Mundigak in Afghanistan and Shahr-i-Sokhta

in eastern Iran.

Helmand

River

The genetic evidence from Shahr-i-Sokhta, the biggest Helmand site,

confirms that the relations with the Harappans were quite strong

with nearly half of all ancient samples from that site considered

to have been migrants from the Harappan region, especially from

Baluchistan and the rest of the ancient samples showing admixture

from these migrants.

According to the French archaeologist, Jean Francois Jarrige, the

principle excavator of Mehrgarh, as stated in this article, the

foundation of Mundigak, the other Helmand site, can be interpreted

as the settling of people from Baluchistan of the Mehrgarh Chalcolithic

tradition and the remains of Period I at Mundigak fit almost perfectly

the cultural assemblage of Mehrgarh Period III.

It is also significant that the pottery of Mundigak I, the earliest

occupation of the “Helmand” cultural complex, corresponds

to the Mehrgarh III pottery, in technique—quality of the paste

and manufacture— as well in the shapes and decoration, probably

within a phase dated to the end of the 5th millennium. The pottery

of Mundigak I-II (fi g. 2: 3-5, 7-8) can also be related to the

context of Balochistan ceramic productions, especially from Mehrgarh

IV around 3500 BC.

The foundation of Mundigak, incidentally dates to around 5000 BC

and is therefore significantly older to the foundation of Shahr-i-Sokhta,

its sister site in Helmand more than 400 kms to its west, whose

earliest dates go only upto 3300 BC and where we have already seen

that the Harappan or Baluchistani migrants were already present

from the earliest period.

While , “..there is general agreement that Shahr-i Sokhta

and Mundigak have the same material culture including similar buff

ceramic material, validating the existence of a Helmand Valley archaeological

culture at the time corresponding to Period I at the former and

Period III at the latter…” it also needs to be understood

that “Shahr-i-Sokhta I nonetheless has inter-regional connections

that are not recorded at Mundigak. In particular, a series of objects

point to contacts to the west…”

With regard to Shahr-i-Sokhta, which in its most expansive phase

was atleast around 150 hect. it should be noted that “…Shahr-i-Sokhta

I is the foundation period of this site and that no other site (or

no context at this site) has been observed thus far in Seistan with

older archaeological deposits. Since no evidence for an older settlement

is observed in this region, the most rational reconstruction is

that Shahr-i Sokhta was founded by communities coming from (an)other

area(s) in the late fourth millennium BCE.” (link same as

above).

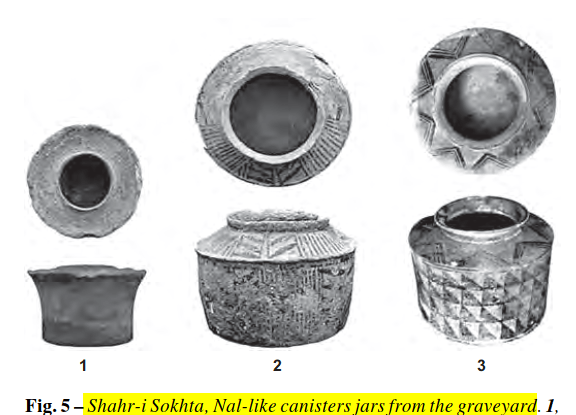

An important provenance study of the Shahr-i-Sokhta ceramics also

indicated a strong influence from the west from the Baluchistani

region and Mundigak. Almost all of the deluxe pottery that was found

at the site and associated with elite graves was of non-local origin

and were imports from the Iranian and Pakistani Baluchistan region.

The authors of this study also observe, “The possibility indeed

remains that, for instance, the cultural assemblage at Mundigak,

or a part of it, belonged to people who later moved to Shahr-i-Sokhta.”

We have already noted earlier how, Mundigak itself likely derives

from the Mehrgarh Chalcolithic tradition of Pakistani Baluchistan.

This tradition, also known as Damb Sadat or Quetta pottery tradition

is one of the 4 major early pottery traditions of Early Harappans.

The strong eastern provenance of the Helmand civilization can be

further appreciated when we see the following material and non-material

connections with the Harappan civilization.

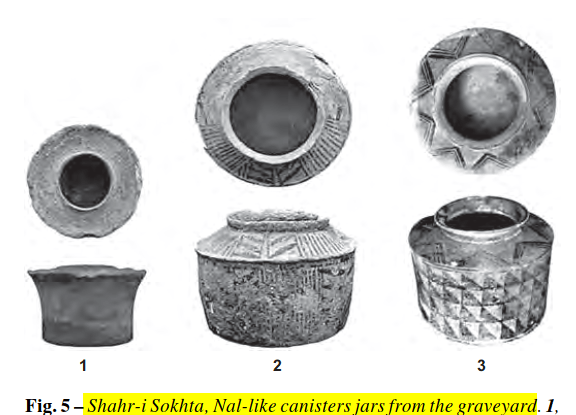

Ceramics :

The cermaics from Shahr-i-Sokhta show similarities with more than

1 type of ceramic traditions of the Early Harappans. There are similarities

with the Quetta or Damb Sadat pottery tradition and infact the earlier

Helmand site of Mundigak is even considered by some as part of that

early Harappan Quetta tradition and established by migrants from

people of the Chalcolithic Mehrgarh tradition, as already noted.

Besides, there is a Southern Baluchistan pottery tradition known

as the Nal which is part of the Amri-Nal culture with Amri tradition

extending into Sindh and Northern Gujarat. This Nal pottery is also

quite prominent at Shahr-i-Sokhta. Finally, there are also some

pottery samples which have been considered to be of the Kot Diji

tradition, an early Harappan culture of Greater Punjab region and

thus from the very heart of the Harappan culture.

A motif found on the potteries at Shahr-i-Sokhta is the pipal leaf

motif. According to archaeologists Vidale and colleagues,

Pipal leaves are a distinctive motif of the pre-Indus ceramic complexes

across wide regions of the Subcontinent; they become very common

in the Kot Dijian phase (approximately 2800-2600 BCE), and often

appear on the famous verres ballon of the Helmand civilization.

The variant with the symmetrical swirling elements is well-known

at Kalibangan, in Haryana, where it occurs in different versions,

painted or incised in a plastic state. Besides such a possible link

with Kalibangan and Haryana, similar sherds are reported from an

enormous region, stretching from Kech Makran, Period IIIb (about

2800-2600 BCE) to Mundigak.

The

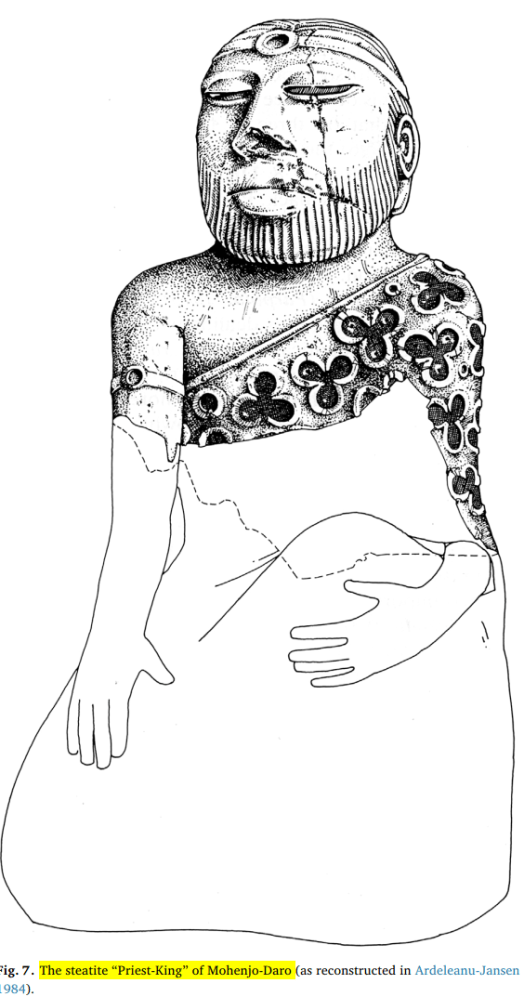

‘Priest-King’ :

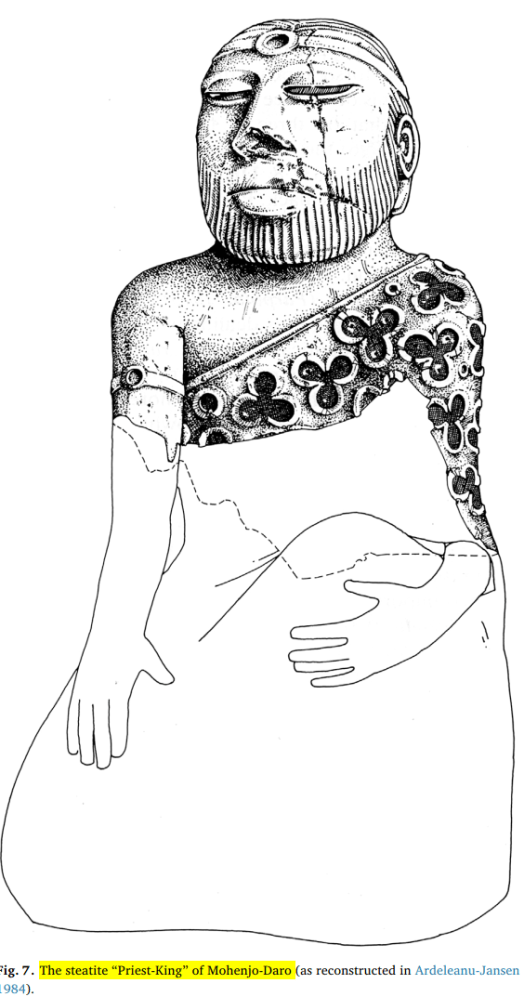

This type of figurine and its fragments, long considered as a Harappan

artifact, is not just limited to the Harappan zone where it is found

at Mohenjo-Daro and Dholavira but also at Helmand sites of Mundigak

and Shahr-i-Sokhta and also in BMAC at Gonur (reference).

Since this figurine (figurine : a statuette, especially one of a

human form) likely gives a very important insight into the socio-cultural

and religious aspects of the people to whom it belonged, the fact

that it was not limited to the Harappan region but was also present

in Eastern Iran and Central Asia further supports the argument of

shared socio-cultural and religious beliefs and values among the

people of these civilizations in the Bronze Age.

Priest-King figurine from Dholavira

Zhob-like

Figurines :

Connected with similar figurines found during the Kot Dijian phase

in Northern Baluchistan.

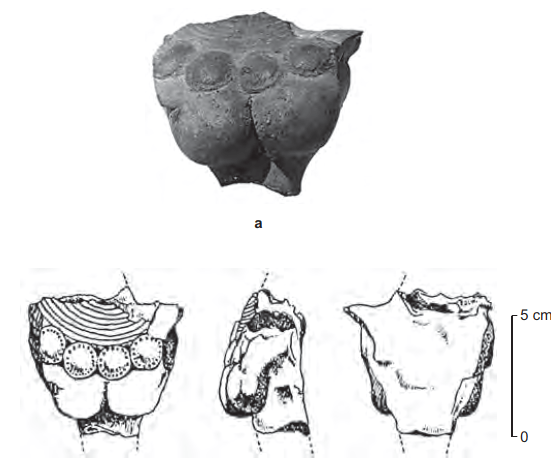

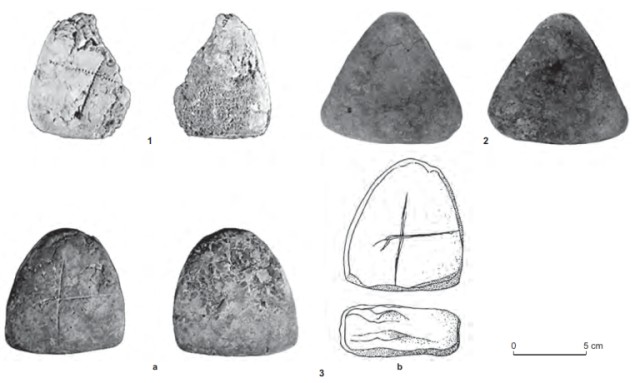

Terracota

Cakes :

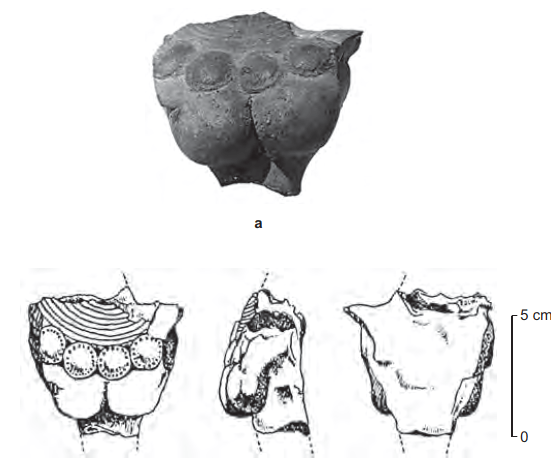

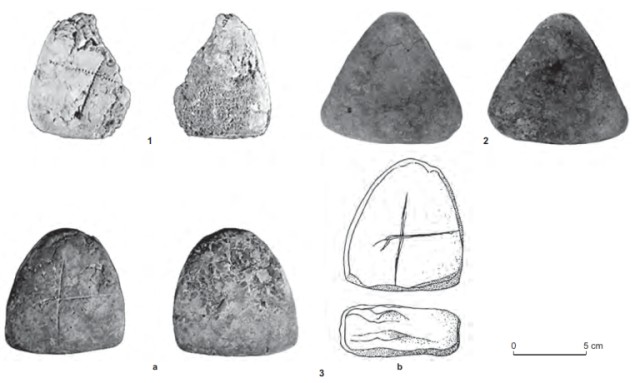

“… Shahr-i Sokhta is the only site in the eastern Iranian

plateau where such terracotta cakes, triangular or more rarely rectangular,

are found in great quantity. Their use, perhaps by families or individuals

having special ties with the Indus region…The most important

group of incised terracotta cakes comes from Lothal, where the record

includes specimens with vertical strokes, central depressions, a

V-shaped sign, a triangle, and a cross-like sign identical to those

found at Shahr-i Sokhta.”

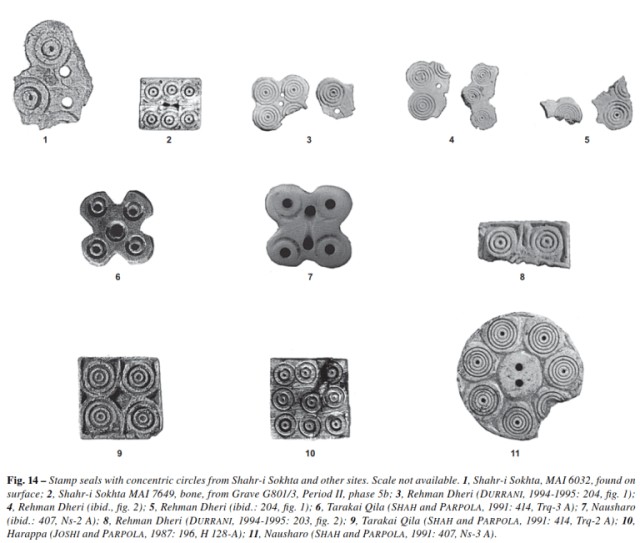

Stamp

Seals :

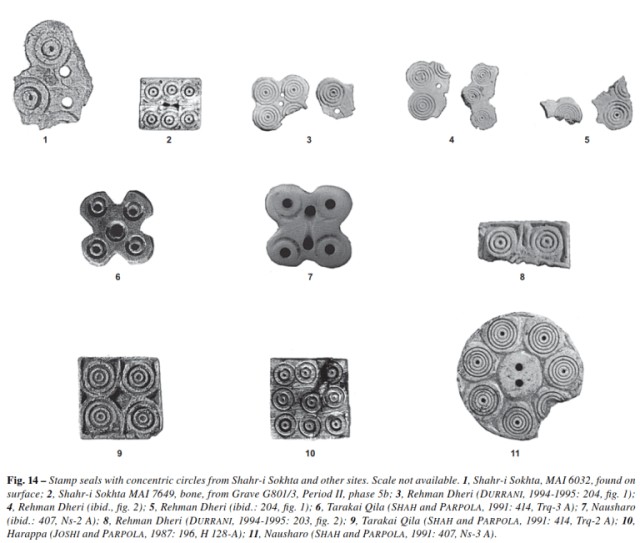

Stamp seals found at Shahr-i-Sokhta are found all across the Harappan

horizon including in its eastern sphere at several sites in Haryana

such as Bhiranna & Banawali.

Steatite

Disk Beads :

“The beads found at Shahr-i Sokhta, in contrast (taken from

the collection in CCXV, cut 3), were morphologically identical to

the Indus specimens; the chemical characterization showed minor

variations from the Indus beads…fi-red steatite disk beads

could have been locally produced at Shahr-i Sokhta with a distinctively

Indus technique. ”

” Etched carnelian beads, another indicator of Indus trade

and exchange activities, are reported from Mundigak. A possible

ivory bead was reported at Shahr-i Sokhta...”

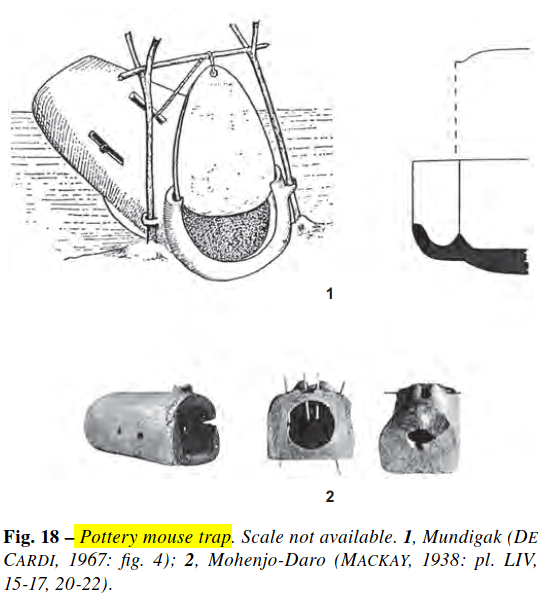

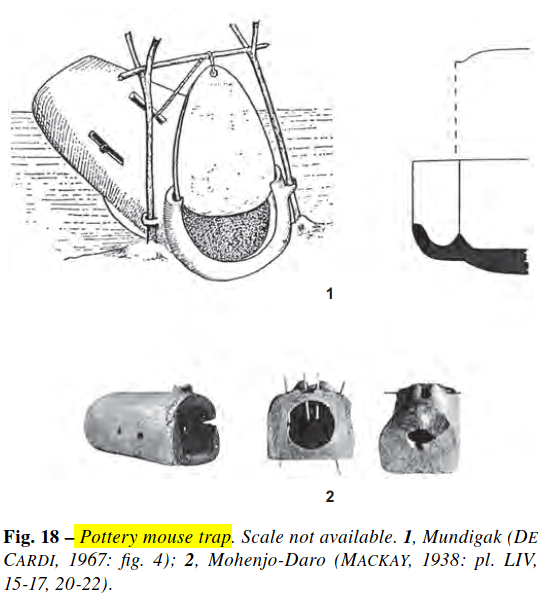

Mouse-Traps

:

“… the overall similarity of the ceramic containers

suggests a parallel adaptation, based upon shared know-how, for

coping with common problems of rodent infestations in the “domestic

universes” of the two civilizations.”

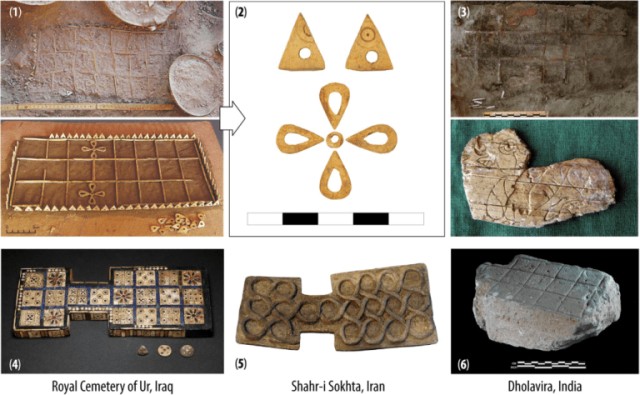

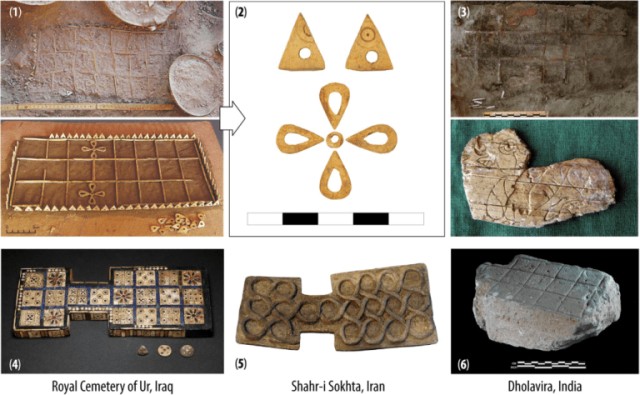

Gaming

pieces, dice and gaming boards :

This was something spread across a wider region and included even

Mesopotamia.

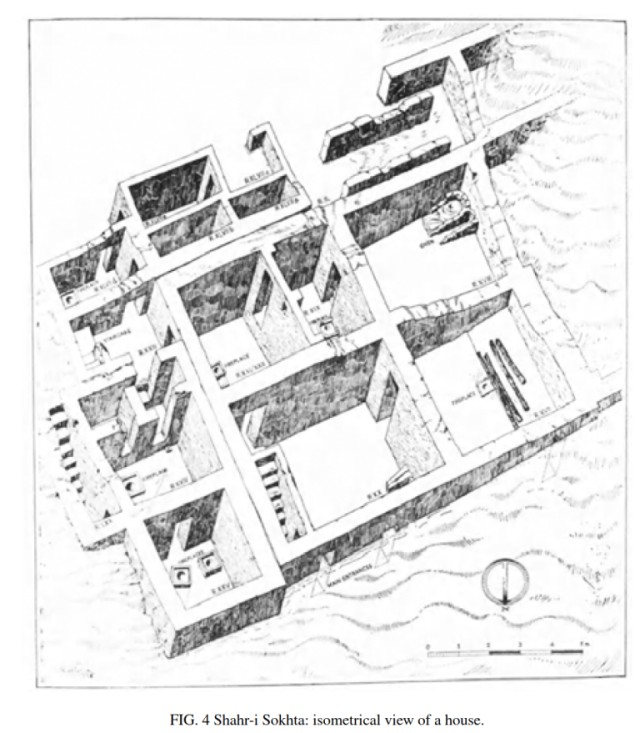

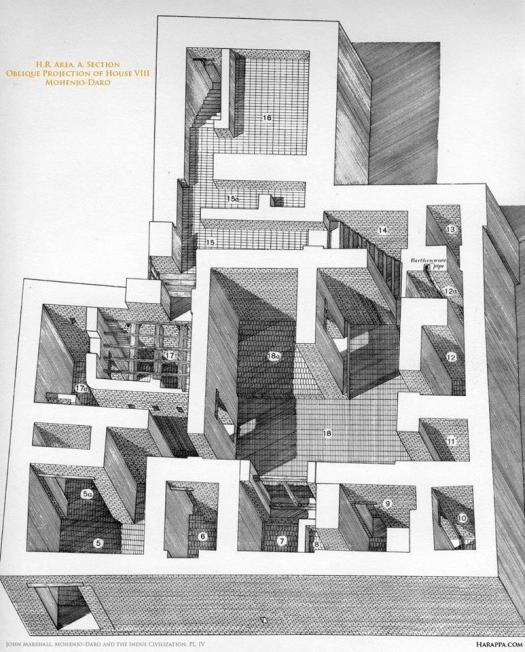

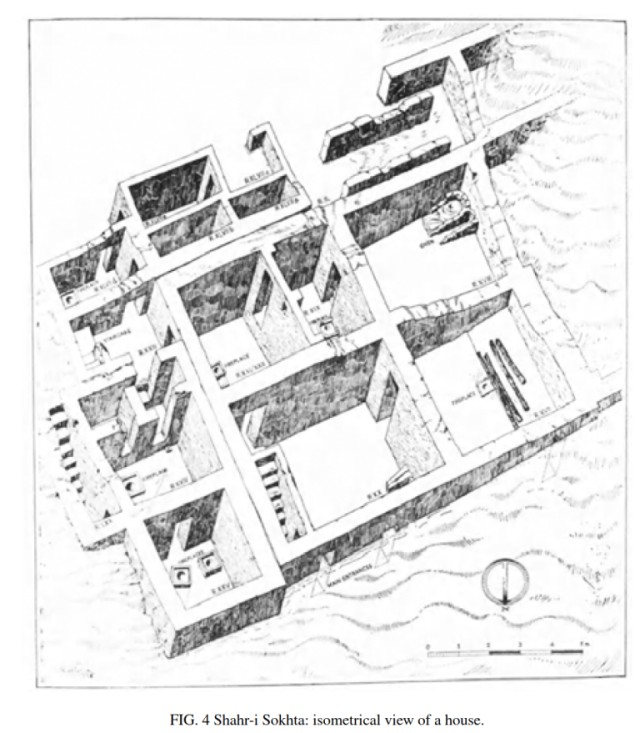

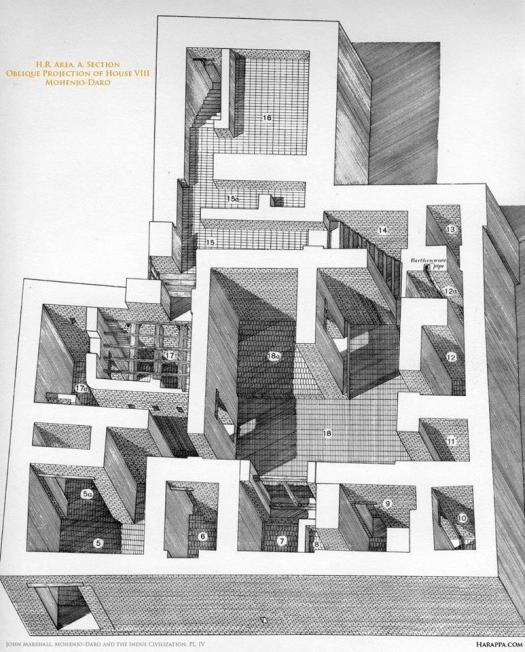

Houses

:

The architecture of Shahr-i-Sokhta is not very well understood but

from what little we know, it appears that the planning of the houses

mirrored those of the Harappans.

The third millennium b.c. dwellings consisted of mud-brick buildings

formed by rather asymmetrical groups of square rooms. The basic

ground-plan was rectangular in shape and covered an area of 90–150

sq m laid out around a courtyard from which the only door providing

access to the exterior opened towards the east…At Shahr-i

Sokhta access to the ground floor was through the external wall

or from one side of the internal courtyard.

Compare the above description with the description of the typical

Harappan house,

Houses range from 1-2 stories in height, with a central courtyard

around which the rooms are arranged…Stairs led to the upper

stories through a side room or the courtyard…

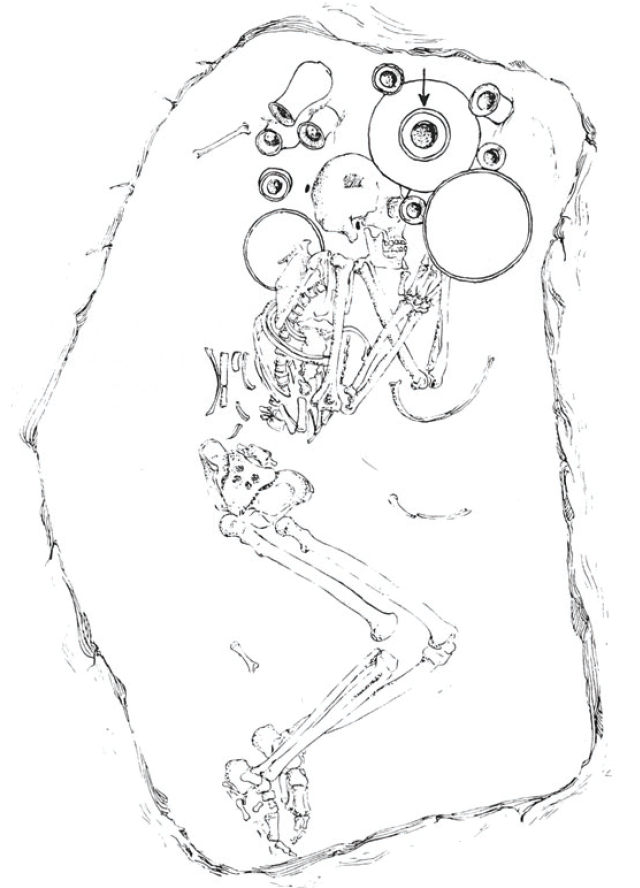

Burials

:

The burials at Shahr-i-Sokhta mostly consisted of simple burial

pits but it also consisted of brick lined graves.

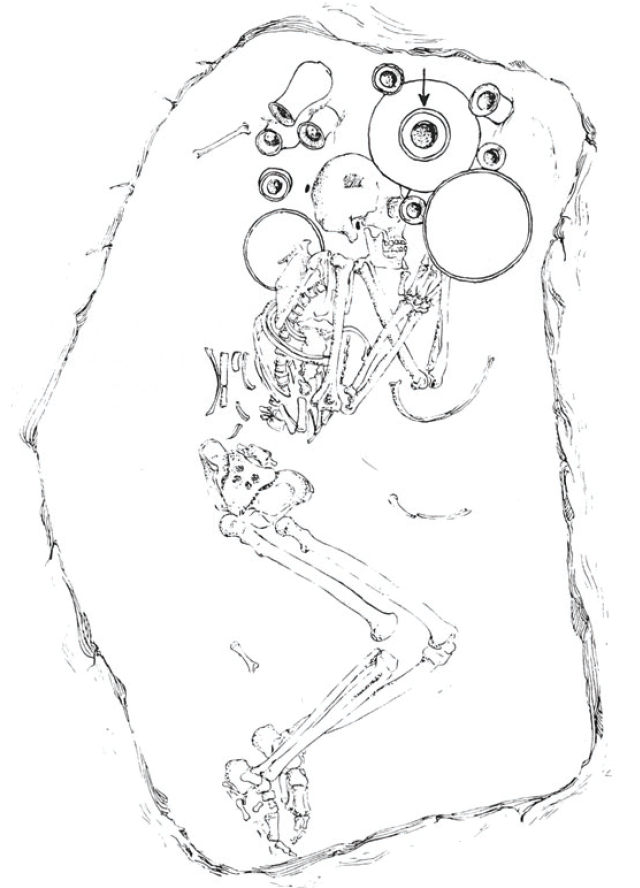

A pit burial from Shahr-i-Sokhta

Typical pit burial from Rakhigarhi

Pit Burials and Brick lined graves are also a feature of Harappan

burials. Most Burials at Harappan sites are oriented North

or northwest. Although, the orientation of Shahr-i-Sokhta

burials is not clear, the burials from the Necropolis of Gonur in

BMAC, which is said to be majorly influenced by Shahr-i-Sokhta,

show a North to Northwest orientation. So a similar burial orientation

at Shahr-i-Sokhta is quite possible.

Another burial practice that the Harappans shared with the people

of the Helmand civilization is the Cenotaph or the symbolic burials

which consisted of an empty burial filled with burial offerings

but devoid of any human remains.

A cenotaph burial from Gonur

Such a peculiar type of burial was found among a small percentage

of burials at Shahr-i-Sokhta and at the site of Gonur in BMAC as

well as across most of the Harappan sites. At Dholavira, for example,

the Cenotaph burial features prominently.

Zebu

Cattle :

A review of the animal remains found at Shahr-i-Sokhta indicates

that while sheep and goats consituted the majority of domestic animals,

cattle consituted the next big number and that among the cattle,

the Zebu clearly predominates.

Based on the animal remains as well as the cattle figurines, 3/4th

of which were of Zebu, it appears the dominant form of cattle at

Shahr-i-Sokhta was of the Zebu type, further confirming the strong

eastern provenance of this major Helmand site.

The above brief review should make it clear that the links between

the Helmand civilization and the Harappan is quite substantial and

fully corroborates the major presence of Eastern migrants as deduced

by the ancient DNA samples from Shahr-i-Sokhta.

Saraswati

and Helmand :

The Helmand river

It may be pertinent to note here that the ancient Saraswati river

of the Rig-ved has been identified with this very same Helmand river

rather than the more natural identification with the Ghaggar-Hakra

by some Indologists. Their contention is that the incoming Indo-Aryans

first settled on the Helmand river in Afghanistan whom they named

as Saraswati. This is based on the argument that the Avestan Harahvaiti,

whom they say is none other than Helmand, is the exact cognate of

Rigvedic Saraswati. Hence, in a Aryan Migration model this very

same Helmand river was also the Rigvedic Saraswati.

However, no archaeological evidence to support such west to east

movement has been presented.

On the other hand, some scholars have argued, on more reasonable

grounds, that the movement of people appears to have been from East

to West, based on Rigvedic and Avestan evidence. There was civilization

in the core Harappan regions of Greater Punjab, Rajasthan, Haryana

and Western UP which parallels the early Vedic geography. Similarly,

there was a civilization on the Helmand river closely related to

the Harappan civilization, which mimics Avestan geography. And the

balance of evidence, as presented here and in the previous post,

clearly indicates migration from the Harappan zone into the Helmand

basin.

Could this archaeological and genetic phenomenon be related to the

migration of early Iranians westwards after their separation from

the early Vedic people ? And might this be how, the name of Vedic

Saraswati, on the dried up bed of which majority of Harappan settlements

now stand, was transposed by the migrating Iranians onto the Helmand

river ? Most assuredly, this is a far more sound argument that what

the invasionists have been able to muster.

It may also be noted that in the Rigved, the camel is an exotic

animal and is mostly associated with the Iranian kings who bring

it as a gift to the Indo-Aryan Purus. Camel is also said to have

played a major role in the economic and social life of the Andronovo

cultural horizon also associated with Indo-Iranians. The latest

archaeological and genetic data shows that the earliest evidence

of camel domestication comes from Eastern Iran and SW Central Asia

from where it most likely spread across Central Asia and the steppe.

The

Importance of Shahr-I-Sokhta :

Shahr-i-Sokhta as a site shows us several features which can an

decisively help us in identifying the place of origin of the Indo-Europeans,

a subject that remains quite contentious to this day.

According to a widely accepted proto-Indo-European reconstruction

the word for wool is said to have been known to the PIE people before

their separation and hence they are believed to have been rearing

sheep for wool. The earliest archaeological evidence of woollen

textiles anywhere across Eurasia is found at none other than the

site of Shahr-i-Sokhta.

Wine-making is also said to have been known to Proto-Indo-Europeans

and it is also attested at Shahr-i-Sokhta.

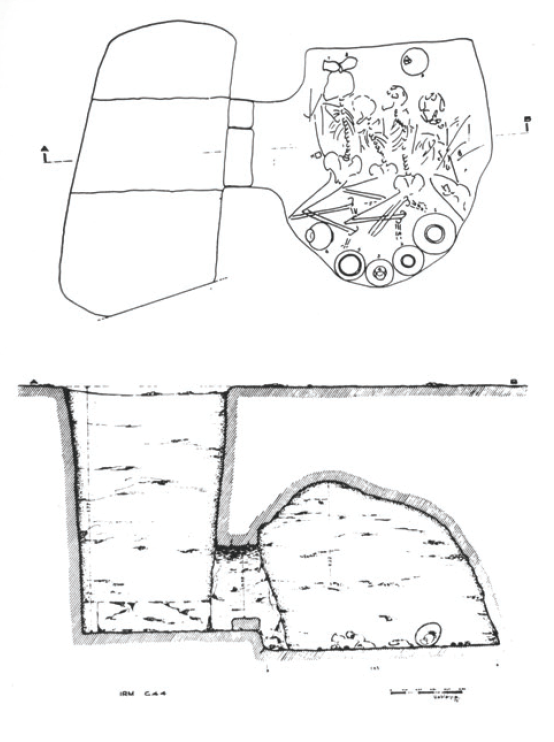

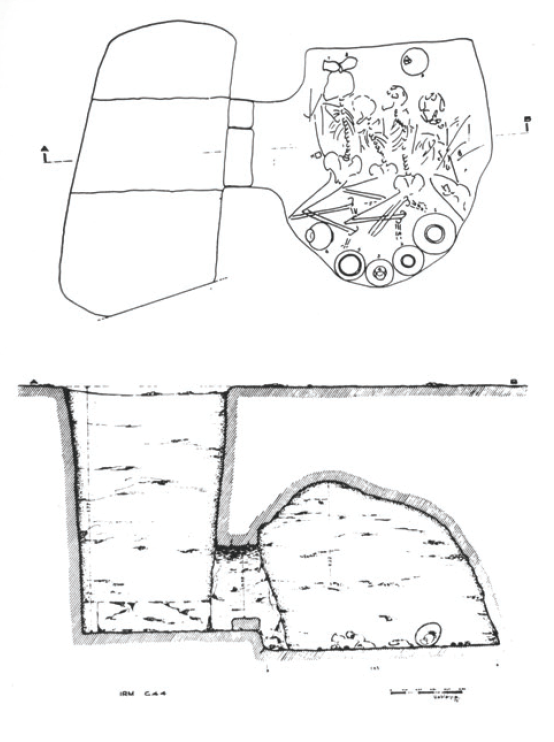

One of the burial types found at Shahr-i-Sokhta which becomes very

common in the BMAC domain is the catacomb burial.

Schematic of a catacomb burial from Shahr-i-Sokhta

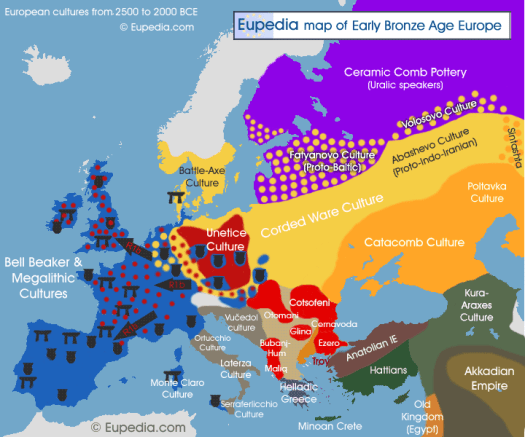

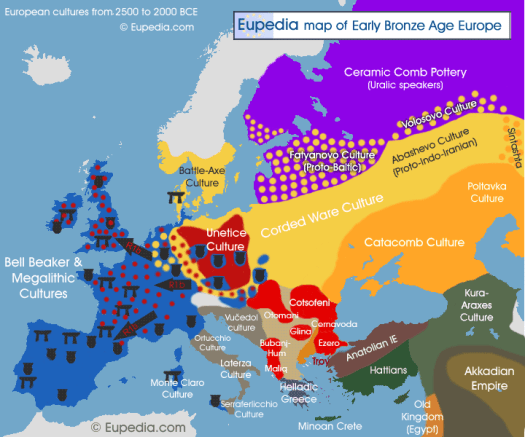

Quite pertinently, one of the successor cultures of the Yamnaya

on the steppe is the culture known as the Catacomb culture which

is considered by some European archaeologists as Indo-Iranian. The

Yamnaya culture is also amazingly enough also known as the Pit-Grave

culture.

This steppe catacomb culture’s origins are likely later than

the earliest catacomb burials found at Shahr-i-Sokhta itself.

Infact, archaeologists had already noted decades back that,

A more complex type of grave has a pit opening into an underground

chamber dug in the clay. At Shahr-i Sokhta it has been found to

have been used for multiple burials accompanied by richer grave

goods. The shape closely recalls that of the later catacomb graves

of southern Siberia and Soviet Central Asia, though it is too early

to say whether there is a common ideological background behind this

convergence.

If the catacomb culture of the steppe was Indo-Iranian, it certainly

needs explaining as to who the people in Eastern Iran and Central

Asia during the Bronze Age were that were also practicing the catacomb

burial.

Source

:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/

2019/11/archaeological-evidence-

for-oit-part-i.html