| EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD (MESOPOTAMIA)

Early Dynastic Period c.2900 – 2350 BC Geographical range : Mesopotamia

Period : Bronze Age

Dates : fl. c. 2900–2350 BC (middle)

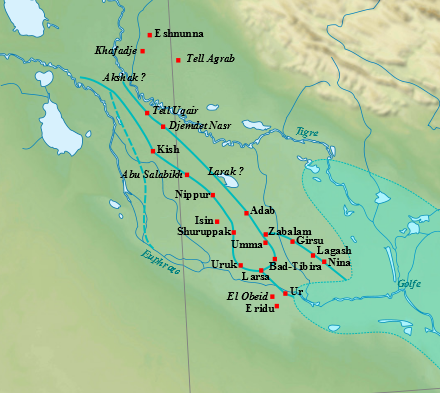

Type site : Tell Khafajah, Tell Agrab, Tell Asmar

Major sites : Tell Abu Shahrain, Tell al-Madain, Tell as-Senkereh, Tell Abu Habbah, Tell Fara, Tell Uheimir, Tell al-Muqayyar, Tell Bismaya, Tell Hariri

Preceded by : Jemdet Nasr Period

Followed by : Akkadian Period

The Early Dynastic period (abbreviated ED period or ED) is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) that is generally dated to c. 2900–2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The ED itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the ED city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.

The study of Central and Lower Mesopotamia has long been given priority over neighboring regions. Archaeological sites in Central and Lower Mesopotamia—notably Girsu but also Eshnunna, Khafajah, Ur, and many others—have been excavated since the 19th century. These excavations have yielded cuneiform texts and many other important artifacts. As a result, this area was better known than neighboring regions, but the excavation and publication of the archives of Ebla have changed this perspective by shedding more light on surrounding areas, such as Upper Mesopotamia, western Syria, and southwestern Iran. These new findings revealed that Lower Mesopotamia shared many socio-cultural developments with neighboring areas and that the entirety of the ancient Near East participated in an exchange network in which material goods and ideas were being circulated.

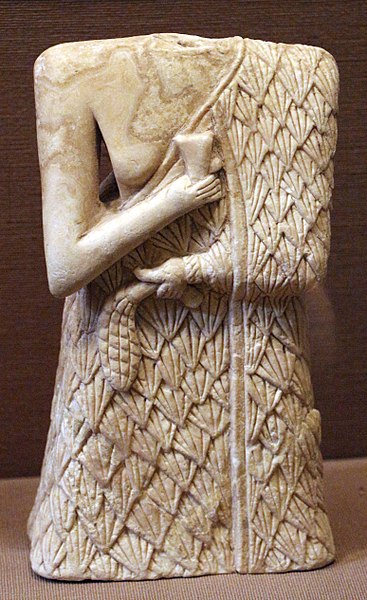

Man carrying a box, possibly for offerings. Metalwork, ca. 2900–2600 BCE, Sumer. Metropolitan Museum of Art History

of research :

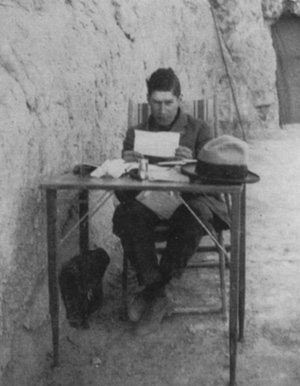

A photograph from the 1930s of Dutch archaeologist Henri Frankfort, who coined the term Early Dynastic period The ED was divided into the sub-periods ED I, II, and III. This was primarily based on complete changes over time in the plan of the Abu Temple of Tell Asmar, which had been rebuilt multiple times on exactly the same spot. During the 20th century, many archaeologists also tried to impose the scheme of ED I–III upon archaeological remains excavated elsewhere in both Iraq and Syria, dated to 3000–2000 BC. However, evidence from sites elsewhere in Iraq has shown that the ED I–III periodization, as reconstructed for the Diyala river valley region, could not be directly applied to other regions.

Research in Syria has shown that developments there were quite different from those in the Diyala river valley region or southern Iraq, rendering the traditional Lower Mesopotamian chronology useless. During the 1990s and 2000s, attempts were made by various scholars to arrive at a local Upper Mesopotamian chronology, resulting in the Early Jezirah (EJ) 0–V chronology that encompasses everything from 3000 to 2000 BC. The use of the ED I–III chronology is now generally limited to Lower Mesopotamia, with the ED II sometimes being further restricted to the Diyala river valley region or discredited altogether.

Periodization

:

Many historical periods in the Near East are named after the dominant political force at that time, such as the Akkadian or Ur III periods. This is not the case for the ED period. It is an archaeological division that does not reflect political developments, and it is based upon perceived changes in the archaeological record, e.g. pottery and glyptics. This is because the political history of the ED is unknown for most of its duration. As with the archaeological subdivision, the reconstruction of political events is hotly debated among researchers.

Scarlet Ware Pottery excavated in Khafajah. 2800-2600 BCE, Early Dynastic II-III, Sumer. British Museum The ED I (2900–2750/2700 BC) is poorly known, relative to the sub-periods that followed it. In Lower Mesopotamia, it shared characteristics with the final stretches of the Uruk (c. 3300–3100 BC) and Jemdet Nasr (c. 3100–2900 BC) periods. ED I is contemporary with the culture of the Scarlet Ware pottery typical of sites along the Diyala in Lower Mesopotamia, the Ninevite V culture in Upper Mesopotamia, and the Proto-Elamite culture in southwestern Iran. [citation needed]

New artistic traditions developed in Lower Mesopotamia during the ED II (2750/2700–2600 BC). These traditions influenced the surrounding regions. According to later Mesopotamian historical tradition, this was the time when legendary mythical kings such as Lugalbanda, Enmerkar, Gilgamesh, and Aga ruled over Mesopotamia. Archaeologically, this sub-period has not been well-attested to in excavations of Lower Mesopotamia, leading some researchers to abandon it altogether.

The ED III (2600–2350 BC) saw an expansion in the use of writing and increasing social inequality. Larger political entities developed in Upper Mesopotamia and southwestern Iran. ED III is usually further subdivided into the ED IIIa (2600–2500/2450 BC) and ED IIIb (2500/2450–2350 BC). The Royal Cemetery at Ur and the archives of Fara and Abu Salabikh date back to ED IIIa. The ED IIIb is especially well known through the archives of Girsu (part of Lagash) in Iraq and Ebla in Syria.

The end of the ED is not defined archaeologically but rather politically. The conquests of Sargon and his successors upset the political equilibrium throughout Iraq, Syria, and Iran. The conquests lasted many years into the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad and built on ongoing conquests during the ED. The transition is much harder to pinpoint within an archaeological context. It is virtually impossible to date a particular site as being that of either ED III or Akkadian period using ceramic or architectural evidence alone.

Early Dynastic kingdoms and rulers :

Map of Iraq showing important sites that were occupied by the Early Dynastic kingdoms The Early Dynastic period is preceded by the Uruk Period (ca. 4000—3100 BCE) and the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3100—2900 BCE). A full list of rulers, some of them legendary, is given by the Sumerian King List (SKL).

The Early Dynastic period is followed by the rise of the Akkadian Empire.

Geographical

context :

Stele of Ushumgal, 2900 - 2700 BC. Probably from Umma The preceding Uruk period in Lower Mesopotamia saw the appearance of the first cities, early state structures, administrative practices, and writing. Evidence for these practices was attested to during the Early Dynastic period.

The ED period is the first for which it is possible to say something about the ethnic composition of the population of Lower Mesopotamia. This is due to the fact that texts from this period contained sufficient phonetic signs to distinguish separate languages. They also contained personal names, which can potentially be linked to an ethnic identity. The textual evidence suggested that Lower Mesopotamia during the ED period was largely dominated by Sumer and primarily occupied by the Sumerian people, who spoke a non-Semitic language isolate (Sumerian). It is debated whether Sumerian was already in use during the Uruk period.

Gold helmet of Meskalamdug, ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur, circa 2500 BC, Early Dynastic period III

Ring of Gold, Carnelian, Lapis Lazuli, Tello, ancient Girsu, mid-3rd millennium BC Textual evidence indicated the existence of a Semitic population in the upper reaches of Lower Mesopotamia. The texts in question contained personal names and words from a Semitic language, identified as Old Akkadian. However, the use of the term Akkadian before the emergence of the Akkadian Empire is problematic [why?], and it has been proposed to refer to this Old Akkadian phase as being of the "Kish civilization" named after Kish (the seemingly most powerful city during the ED period) instead. Political and socioeconomic structures in these two regions also differed, although Sumerian influence is unparalleled during the Early Dynastic period.

Agriculture in Lower Mesopotamia relied on intensive irrigation. Cultivars included barley and date palms in combination with gardens and orchards. Animal husbandry was also practiced, focusing on sheep and goats. This agricultural system was probably the most productive in the entire ancient Near East. It allowed the development of a highly urbanized society. It has been suggested that, in some areas of Sumer, the population of the urban centers during ED III represented three-quarters of the entire population.

Irrigated palm grove along the banks of the Euphrates River, in modern-day Southern Iraq. This landscape has remained unchanged since earliest antiquity The dominant political structure was the city-state in which a large urban center dominated the surrounding rural settlements. The territories of these city-states were in turn delimited by other city-states that were organized along the same principles. The most important centers were Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Adab, and Umma-Gisha. Available texts from this period point to recurring conflicts between neighboring kingdoms, notably between Umma and Lagash.

The situation may have been different further north, where Semitic people seem to have been dominant. In this area, Kish was possibly the center of a large territorial state, competing with other powerful political entities such as Mari and Akshak.

The Diyala River valley is another region for which the ED period is relatively well-known. Along with neighboring areas, this region was home to Scarlet Ware—a type of painted pottery characterized by geometric motifs representing natural and anthropomorphic figures. In the Jebel Hamrin, fortresses such as Tell Gubba and Tell Maddhur were constructed. It has been suggested [by whom?] that these sites were established to protect the main trade route from the Mesopotamian lowlands to the Iranian plateau. The main Early Dynastic sites in this region are Tell Asmar and Khafajah. Their political structure is unknown, but these sites were culturally influenced by the larger cities in the Mesopotamian lowland.

Neighboring

regions :

Starting in 2700 BC and accelerating after 2500, the main urban sites grew considerably in size and were surrounded by towns and villages that fell inside their political sphere of influence. This indicated that the area was home to many political entities. Many sites in Upper Mesopotamia, including Tell Chuera and Tell Beydar, shared a similar layout: a main tell surrounded by a circular lower town. German archaeologist Max von Oppenheim called them Kranzhügel, or “cup-and-saucer-hills”. [citation needed] Among the important sites of this period are Tell Brak (Nagar), Tell Mozan, Tell Leilan, and Chagar Bazar in the Jezirah and Mari on the middle Euphrates.

Map detailing the First Eblaite Kingdom at its height c. 2340 BC

Map detailing the Second Mariote Kingdom at its height c. 2290 BC Urbanization also increased in western Syria, notably in the second half of the third millennium BC. Sites like Tell Banat, Tell Hadidi, Umm el-Marra, Qatna, Ebla, and Al-Rawda developed early state structures, as evidenced by the written documentation of Ebla. Substantial monumental architecture such as palaces, temples, and monumental tombs appeared in this period. There is also evidence for the existence of a rich and powerful local elite.

The two cities of Mari and Ebla dominate the historical record for this region. According to the excavator of Mari, the circular city on the middle Euphrates was founded ex nihilo at the time of the Early Dynastic I period in Lower Mesopotamia. Mari was one of the main cities of the Middle East during this period, and it fought many wars against Ebla during the 24th century BC. The archives of Ebla, capital city of a powerful kingdom during the ED IIIb period, indicated that writing and the state were well-developed, contrary to what had been believed about this area before its discovery. However, few buildings from this period have been excavated at the site of Ebla itself.

The territories of these kingdoms were much larger than in Lower Mesopotamia. Population density, however, was much lower than in the south where subsistence agriculture and pastoralism were more intensive. Towards the west, agriculture takes on more "Mediterranean" aspects: the cultivation of olive and grape was very important in Ebla. Sumerian influence was notable in Mari and Ebla. At the same time, these regions with a Semitic population shared characteristics with the Kish civilization while also maintaining their own unique cultural traits.

Iranian

Plateau :

Map detailing the approximate locations of regions and kingdoms that are known from Mesopotamian written evidence of the third millennium BC In the middle third millennium BC, Elam emerged as a powerful political entity in the area of southern Lorestan and northern Khuzestan. Susa (level IV) was a central place in Elam and an important gateway between southwestern Iran and southern Mesopotamia. Hamazi was located in the Zagros Mountains to the north or east of Elam, possibly between the Great Zab and the Diyala River, near Halabja.

This is also the area where the still largely unknown Jiroft culture emerged in the third millennium BC, as evidenced by excavation and looting of archaeological sites. The areas further north and to the east were important participants in the international trade of this period due to the presence of tin (central Iran and the Hindu Kush) and lapis lazuli (Turkmenistan and northern Afghanistan). Settlements such as Tepe Sialk, Tureng Tepe, Tepe Hissar, Namazga-Tepe, Altyndepe, Shahr-e Sukhteh, and Mundigak served as local exchange and production centres but do not seem to have been capitals of larger political entities.

Persian

Gulf :

Further to the west was an area called Dilmun, which in later periods corresponds to what is today known as Bahrain. However, while Dilmun was mentioned in contemporary ED texts, no sites from this period have been excavated in this area. This may indicate that Dilmun may have referred to the coastal areas that served as a place of transit for the maritime trade network.

Indus valley :

Some of the carnelian beads in this necklace from the Royal Tombs of Ur are thought to have come from the Indus Valley The maritime trade in the Gulf extended as far east as the Indian subcontinent, where the Indus Valley Civilisation flourished. This trade intensified during the third millennium and reached its peak during the Akkadian and Ur III periods.

The artifacts found in the royal tombs of the First Dynasty of Ur indicate that foreign trade was particularly active during this period, with many materials coming from foreign lands, such as Carnelian likely coming from the Indus or Iran, Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan, silver from Turkey, copper from Oman, and gold from several locations such as Egypt, Nubia, Turkey or Iran. Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600–2450, in an example of Indus-Mesopotamia relations. In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique developed by the Harappans. These materials were used in the manufacture of ornamental and ceremonial objects in the workshops of Ur.

The First Dynasty of Ur had enormous wealth as shown by the lavishness of its tombs. This was probably due to the fact that Ur acted as the main harbour for trade with India, which put her in a strategic position to import and trade vast quantities of gold, carnelian or lapis lazuli. In comparison, the burials of the kings of Kish were much less lavish. High-prowed Summerian ships may have traveled as far as Meluhha, thought to be the Indus region, for trade.

Government

and economy :

Lugaldalu, king of Adab, circa 2500 BCE

Detail of the inscription with archaic cuneiform Lugaldalu Each city was centered around a temple that was dedicated to a particular patron deity. A city was governed by both/either a "lugal" (king) and/or an "ensi" (priest). It was understood that rulers were determined by the deity of the city and rule could be transferred from one city to another. Hegemony from the Nippur priesthood moved between competing dynasties of the Sumerian cities. Traditionally, these included Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larsa, Sippar, Shuruppak, Kish, Uruk, Ur, Adab, and Akshak. Other relevant cities from outside the Tigris–Euphrates river system included Hamazi, Awan (in present-day Iran), and Mari (in present-day Syria but which is credited on the SKL as having "exercised kingship" during the ED II period).

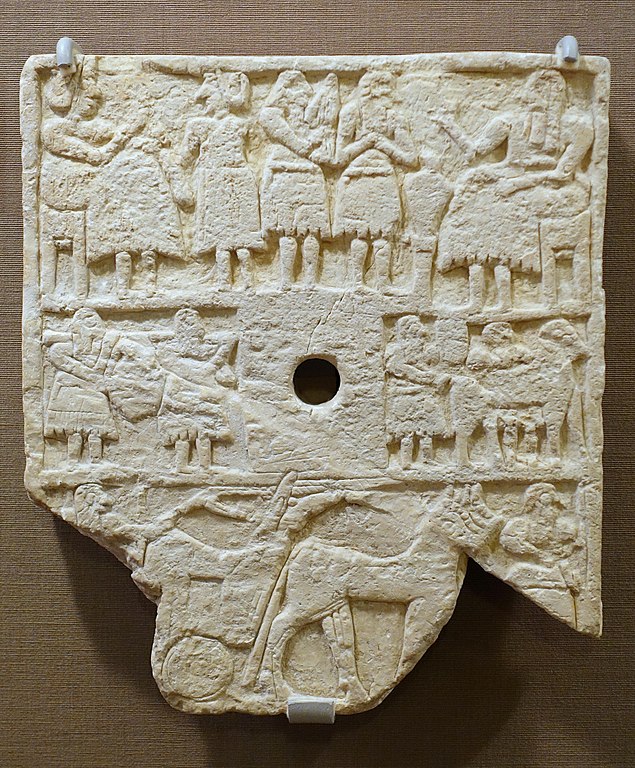

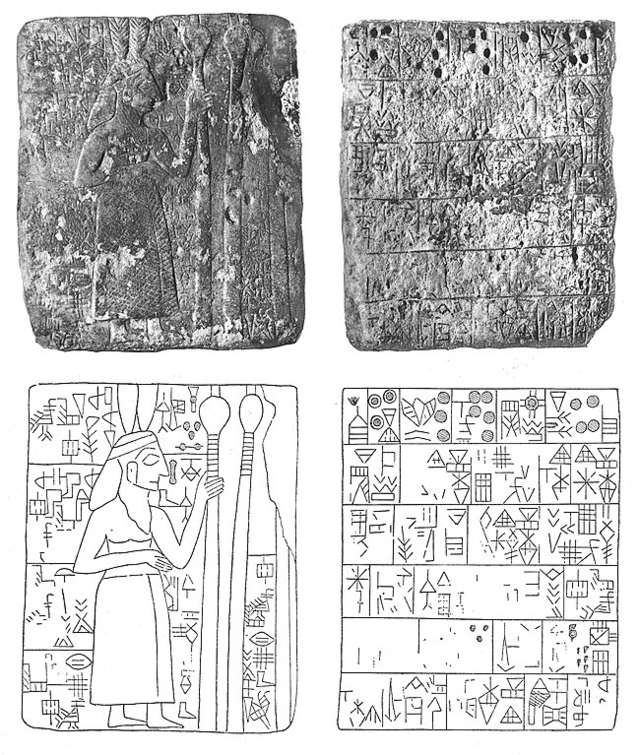

Votive relief for the king Ur-Nanshe of Lagash, commemorating the construction of a temple Thorkild Jacobsen defined a "primitive democracy" with reference to Sumerian epics, myths, and historical records. He described a form of government determined by a majority of men who were free citizens. There was little specialisation and only a loose power structure. Kings such as Gilgamesh of the first dynasty of Uruk did not yet hold an autocracy. Rather, they governed together with councils of elders and councils of younger men, who were likely free men bearing arms. Kings would consult the councils on all major decisions, including whether to go to war. Jacobsen's definition of a democracy as a relationship between primitive monarchs and men of the noble classes has been questioned. Jacobsen conceded that the available evidence could not distinguish a "Mesopotamian democracy" from a "primitive oligarchy".

"Lugal" (Sumerian: a Sumerogram ligature of two signs: meaning "big" or "great" and meaning "man") (a Sumerian language title translated into English as either "king" or "ruler") was one of three possible titles affixed to a ruler of a Sumerian city-state. The others were "EN" and "ensi".

The sign for "lugal" became the understood logograph for "king" in general. In the Sumerian language, "lugal" meant either an "owner" of property such as a boat or a field, or alternatively, the "head" of an entity or a family. The cuneiform sign for "lugal" serves as a determinative in cuneiform texts, indicating that the following word would be the name of a king.

The definition of "lugal" during the ED period of Mesopotamia is uncertain. The ruler of a city-state was usually referred to as "ensi". However, the ruler of a confederacy may have been referred to as "lugal". A lugal may have been "a young man of outstanding qualities from a rich landowning family". [citation needed]

Jacobsen made a distinction between a "lugal" as an elected war leader and "EN" as an elected governor concerned with internal issues. The functions of a lugal might include military defense, arbitration in border disputes, and ceremonial and ritualistic activities. At the death of the lugal, he was succeeded by his eldest son. The earliest rulers with the title "lugal" include Enmebaragesi and Mesilim of Kish and Meskalamdug, Mesannepada, and several of Mesannepada's successors at Ur.

"Ensi" (Sumerian: B464ellst.png C+B-Babylonia-CuneiformImage16.PNG B181ellst.png, meaning "Lord of the Plowland") was a title associated with the ruler or prince of a city. The people understood that the ensi was a direct representative of the city's patron deity. Initially, the term "ensi" may have been specifically associated with rulers of Lagash and Umma. However, in Lagesh, "lugal" sometimes referred to the city's patron deity, "Ningirsu". In later periods, the title "ensi" presupposed subordinance to a "lugal".

"EN" (Sumerian: Sumerian cuneiform for "lord" or "priest") referred to a high priest or priestess of the city's patron deity. It may also have been part of the title of the ruler of Uruk. "Ensi", "EN", and "Lugal" may have been local terms for the ruler of Lagash, Uruk, and Ur, respectively.

Temples :

Early religious relief (c.2700 BCE)

Carved figure with feathers. The king-priest, wearing a net skirt and a hat with leaves or feathers, stands before the door of a temple, symbolized by two great maces. The inscription mentions the god Ningirsu. Early Dynastic Period, circa 2700 BCE, Girsu.

Wall plaque from Ur, with image of a temple (lower right). Circa 2500 BCE. British Museum The centers of Eridu and Uruk, two of the earliest cities, developed large temple complexes built of mud-brick. Developed as small shrines in the earliest settlements, by the ED the temples became the most imposing structures in their cities, each dedicated to its own deity.

Each city had at least one major deity. Sumer was divided into about thirteen independent cities which were divided by canals and boundary stones during the ED. According to the Sumerian King List (SKL), the first five cities—listed with their principal temple complexes and patron deities—to have exercised kingship before "The Flood" were :

Population :

Funeral procession at the Royal Cemetery of Ur (items and positions in tomb PG 789), circa 2600 BCE (reconstitution)

Female statuette, with cup and bracelet, Khafajah, 2650 - 2550 BCE Uruk, which was one of Sumer's largest cities, has been estimated to have had a population of 50,000 – 80,000 at its peak. Given the other cities in Sumer and its large agricultural population, a rough estimate for Sumer's population might have been somewhere between 800,000 and 1,500,000. The global human population at this time has been estimated to have been about 27,000,000.

Table 1 : 2800 BC – 2300 BC

Law :

Code of Urukagina :

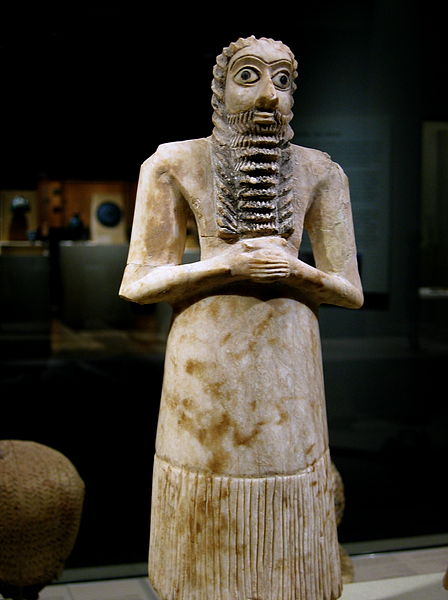

Statuette of a man, Early Dynastic Period II, circa 2700 BC, Khafadje. Louvre Museum, reference AO 188886 The énsi Urukagina, of the city-state of Lagash, is best known for his reforms to combat corruption, and the Code of Urukagina is sometimes cited as the earliest known example of a legal code in recorded history. The Code of Urukagina has also been widely hailed as the first recorded example of government reform, as it sought to achieve a higher level of freedom and equality. Although the actual Code of Urukagina text has yet to be discovered, much of its content may be surmised from other references to it that have been found. In the Code of Urukagina, Urukagina exempted widows and orphans from taxes, compelled the city to pay funeral expenses (including the ritual food and drink libations for the journey of the dead into the lower world), and decreed that the rich had to use silver when purchasing from the poor. If the poor did not wish to sell, the powerful man (the rich man or the priest) could not force him to do so. The Code of Urukagina limited the power of both the priesthood and large property owners and established measures against usury, burdensome controls, hunger, theft, murder, and seizure of people's property and persons—as Urukagina stated: "The widow and the orphan were no longer at the mercy of the powerful man."

Despite these attempts to curb the excesses of the elite class, elite or royal women may have had even greater influence and prestige in Urukagina's reign than previously. Urukagina greatly expanded the royal "Household of Women" from about 50 persons to about 1,500 persons and renamed it to "Household of Goddess Bau". He gave it ownership of vast amounts of land confiscated from the former priesthood and placed it under the supervision of Urukagina's wife Shasha, or Shagshag. During the second year of Urukagina's reign, his wife presided over the lavish funeral of his predecessor's queen Baranamtarra, who had been an important personage in her own right.

In addition to such changes, two of Urukagina's other surviving decrees, first published and translated by Samuel Kramer in 1964, have attracted controversy in recent decades :

No comparable laws from Urukagina addressing penalties for adultery by men have survived. The discovery of these fragments has led some modern critics to assert that they provide "the first written evidence of the degradation of women."

Reform Document :

Summerian cylinder seal, ca. 2500–2350 BC. Early Dynastic IIIb The following extracts are taken from the "Reform Document" :

Trade :

The "Ram in a Thicket" statue found at the Royal Cemetery of Ur contains traded materials

Chlorite vase from Khafaje Imports to Ur came from the Near East and the Old World. Goods such as obsidian from Turkey, lapis lazuli from Badakhshan in Afghanistan, beads from Bahrain, and seals inscribed with the Indus Valley script from India have been found in Ur. Metals were imported. Sumerian stonemasons and jewelers used gold, silver, lapis lazuli, chlorite, ivory, iron, and carnelian. Resin from Mozambique was found in the tomb of Queen Puabi at Ur.

The cultural and trade connections of Ur are reflected by archaeological finds of imported items. In the ED III period, items from geographically distant places were found. These included gold, silver, lapis lazuli and carnelian. These types of items were not found in Mesopotamia.

Gold items were located in graves at the Royal Cemetery of Ur, royal treasuries and temples, indicating prestigious and religious functions. Gold items discovered included personal ornaments, weapons, tools, sheet-metal cylinder seals, fluted bowls, goblets, imitation cockle shells, and sculptures.

Silver was found as items such as belts, vessels, hair ornaments, pins, weapons, cockle shells, and sculptures. There are very few literary references or physical clues as to the sources of the silver.

Lapis lazuli has been found in items such as jewelry, plaques, gaming boards, lyres, ostrich-egg vessels, and also in parts of a larger sculpture known as Ram in a Thicket. Some of the larger objects included a spouted cup, a dagger-hilt, and a whetstone. It indicates high status.

Chlorite stone artifacts from the ED are commonly found. they include disc beads, ornaments, and stone vases. The vases rarely exceed 25 cm in height. They often have human and animal motifs and semiprecious stone inlays. They may have carried precious oils.

History

:

For the ED I and ED II periods, there are no contemporary documents shedding any light on warfare or diplomacy. Only for the end of the ED III period are contemporary texts available from which a political history can be reconstructed. The largest archives come from Lagash and Ebla. Smaller collections of clay tablets have been found at Ur, Tell Beydar, Tell Fara, Abu Salabikh, and Mari. They show that the Mesopotamian states were constantly involved in diplomatic contacts, leading to political and perhaps even religious alliances. Sometimes one state would gain hegemony over another, which foreshadows the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The well-known Sumerian King List dates to the early second millennium BC. It consists of a succession of royal dynasties from different Sumerian cities, ranging back into the Early Dynastic Period. Each dynasty rises to prominence and dominates the region, only to be replaced by the next. The document was used by later Mesopotamian kings to legitimize their rule. While some of the information in the list can be checked against other texts such as economic documents, much of it is probably fictional, and its use as a historical document is limited.

Diplomacy :

Foundation nail commemorating the peace treaty between Entemena of Lagash and Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk (c. 2500 BC) There may have been a common or shared cultural identity among the Early Dynastic Sumerian city-states, despite their political fragmentation. This notion was expressed by the terms kalam or ki-engir. Numerous texts and cylinder seals seem to indicate the existence of a league or amphictyony of Sumerian city-states. For example, clay tablets from Ur bear cylinder seal impressions with signs representing other cities. Similar impressions have also been found at Jemdet Nasr, Uruk, and Susa. Some impressions show exactly the same list of cities. It has been suggested that this represented a system in which specific cities were associated with delivering offerings to the major Sumerian temples, similar to the bala system of the Ur III period.

Gold objects from tomb PG 580, Royal Cemetery at Ur, 26th century BC, Early Dynasic Period III The texts from Shuruppak, dating to ED IIIa, also seem to confirm the existence of a ki-engir league. Member cities of the alliance included Umma, Lagash, Uruk, Nippur, and Adab. Kish may have had a leading position, whereas Shuruppak may have been the administrative center. The members may have assembled in Nippur, but this is uncertain. This alliance seems to have focused on economic and military collaboration, as each city would dispatch soldiers to the league. The primacy of Kish is illustrated by the fact that its ruler Mesilim (c. 2500 BC) acted as arbitrator in a conflict between Lagash and Umma. However, it is not certain whether Kish held this elevated position during the entire period, as the situation seems to have been different during later conflicts between Lagash and Umma. Later, rulers from other cities would use the title 'King of Kish' to strengthen their hegemonic ambitions and possibly also because of the symbolic value of the city.

The texts of this period also reveal the first traces of a wide-ranging diplomatic network. For example, the peace treaty between Entemena of Lagash and Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk, recorded on a clay nail, represents the oldest known agreement of this kind. Tablets from Girsu record reciprocal gifts between the royal court and foreign states. Thus, Baranamtarra, wife of king Lugalanda of Lagash, exchanged gifts with her peers from Adab and even Dilmun.

War

:

It is only for the later parts of the ED period that information on political events becomes available, either as echoes in later writings or from contemporary sources. Writings from the end of the third millennium, including several Sumerian heroic narratives and the Sumerian King List, seem to echo events and military conflicts that may have occurred during the ED II period. For example, the reigns of legendary figures like king Gilgamesh of Uruk and his adversaries Enmebaragesi and Aga of Kish possibly date to ED II. These semi-legendary narratives seem to indicate an age dominated by two major powers: Uruk in Sumer and Kish in the Semitic country. However, the existence of the kings of this "heroic age" remains controversial.

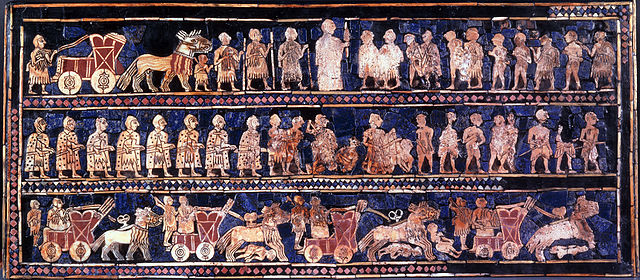

The "War" panel of the Standard of Ur showing combatants engaged in military activities. Dated to c. 2600 BC

One fragment of the Stele of the Vultures showing king Eannatum as a military charioteer. Dated to c. 2450 B.C. Currently in the Louvre Museum Somewhat reliable information on then-contemporary political events in Mesopotamia is available only for the ED IIIb period. These texts come mainly from Lagash and detail the recurring conflict with Umma over control of irrigated land. The kings of Lagash are absent from the Sumerian King List, as are their rivals, the kings of Umma. This suggests that these states, while powerful in their own time, were later forgotten.

The royal inscriptions from Lagash also mention wars against other Lower Mesopotamian city-states, as well as against kingdoms farther away. Examples of the latter include Mari, Subartu, and Elam. These conflicts show that already in this stage in history there was a trend toward stronger states dominating larger territories. For example, king Eannatum of Lagash was able to defeat Mari and Elam around 2450 B.C. Enshakushanna of Uruk seized Kish and imprisoned its king Embi-Ishtar around 2350 B.C. Lugal-zage-si, king of Uruk and Umma, was able to seize most of Lower Mesopotamia around 2358 B.C. This phase of warring city-states came to an end with the emergence of the Akkadian Empire under the rule of Sargon of Akkad in 2334 B.C. (middle).

Neighboring

areas :

Recent

discoveries :

Culture

:

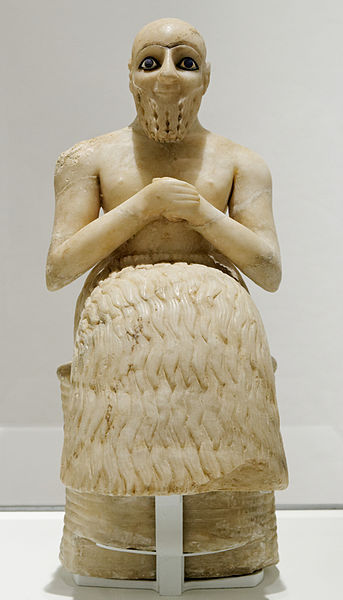

Statue of a male figure, recovered from Tell Asmar

Statue of a female figure, recovered from Khafajah

Statue of a kneeling male figure holding a vase, recovered from Tell Agrab

Statue of Ebih-Il, recovered from Mari (ED IIIb)

Stone statue of Kurlil, Early Dynastic III, 2500 BC Tell Al-'Ubaid Bas-reliefs created from perforated stone slabs are another hallmark of Early Dynastic sculpture. They also served a votive purpose, but their exact function is unknown. Examples include the votive relief of king Ur-Nanshe of Lagash and his family found at Girsu and that of Dudu, a priest of Ningirsu. The latter showed mythological creatures such as a lion-headed eagle. The Stele of the Vultures, created by Eannatum of Lagash, is remarkable in that it represents different scenes that together tell the narrative of the victory of Lagash over its rival Umma. Reliefs like these have been found in Lower Mesopotamia and the Diyala region but not in Upper Mesopotamia or Syria.

Bas-relief of a banquet and boating scene, unknown provenience

Bas-relief of a banquet scene, recovered from Tell Agrab

Banquet scene, Khafajah, 2650 - 2550 BCE

Votive relief of the priest Dudu, of the time of Entemena, recovered from Girsu. Circa 2400 BCE Metalworking

and goldsmithing :

Numerous metal objects have been excavated from temples and graves, including dishes, weapons, jewelry, statuettes, foundation nails, and various other objects of worship. The most remarkable gold objects come from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, including musical instruments and the complete inventory of Puabi’s tomb. Metal vases have also been excavated at other sites in Lower Mesopotamia, including the Vase of Entemena at Lagash.

Statue of a bull (ED III)

Vessel stand in the shape of an ibex. Copper-based alloy with nacre and lapis lazuli inlays, created with the lost-wax method (ED III)

Reconstructed headgear of Puabi, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur (ED III)

Gold objects from the Royal Cemetery at Ur

Animal-shaped pendants of gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian from Eshnunna

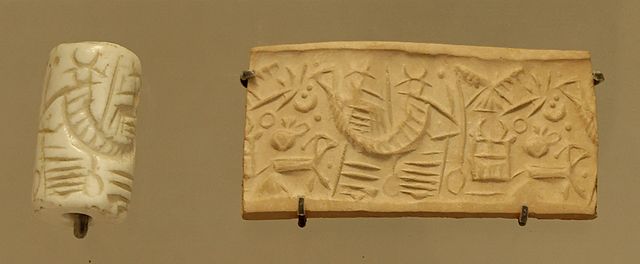

Pearl, lapis lazuli, carnelian and silver beads from Tell Agrab (ED I) Cylinder seals :

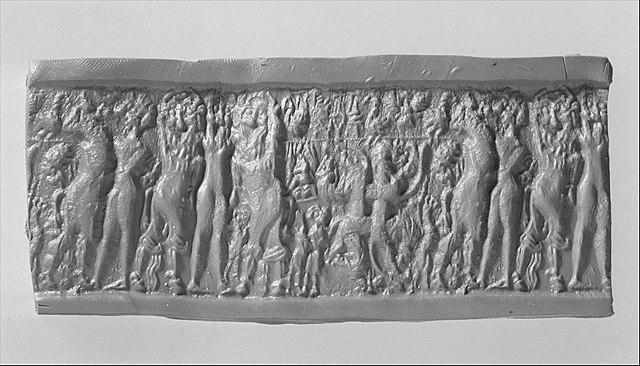

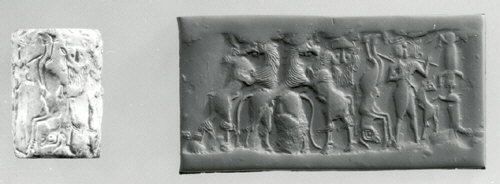

Cylinder seal from the ED III period with its impression representing a mythological combat scene

Cylinder seal and modern impression bull-man, bearded hero, and lion contest frieze, ca. 2600 – 2350 B.C. Early Dynastic III Cylinder seals were used to authenticate documents like sales and to control access by sealing a lump of clay on doors of storage rooms. The use of cylinder seals increased significantly during the ED period, suggesting an expansion and increased the complexity of administrative activities.

During the preceding Uruk period, a wide variety of scenes were engraved on cylinder seals. This variety disappeared at the start of the third millennium, to be replaced by an almost exclusive focus on mythological and cultural scenes in Lower Mesopotamia and the Diyala region. During the ED I period, seal designs included geometric motifs and stylized pictograms. Later on, combat scenes between real and mythological animals became the dominant theme, together with scenes of heroes fighting animals. Their exact meaning is unclear. Common mythological creatures include anthropomorphic bulls and scorpion-men. Real creatures include lions and eagles. Some anthropomorphic creatures are probably deities, as they wear a horned tiara, which was a symbol of divinity.

Scenes with cultic themes, including banquet scenes, became common during ED II. Another common ED III theme was the so-called god-boat, but its meaning is unclear. During the ED III period, ownership of seals was started to be registered. Glyptic development in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria was strongly influenced by Sumerian art.

Inlays :

Alabaster bull inlay. From southern Iraq, Early Dynastic Period, c. 2750 - 2400 BC. The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, UK

Piece of inlay made of nacre, inscribed with the name of Akurgal, son of Ur-Nanshe of Lagash (currently in the Louvre) Examples of inlay have been found at several sites and used materials such as nacre (mother of pearl), white and coloured limestone, lapis lazuli, and marble. Bitumen was used to attach the inlay in wooden frames, but these have not survived in the archaeological record. The inlay-panels usually showed mythological or historical scenes. Like bas-reliefs, these panels allow the reconstruction of early forms of narrative art. However, this type of work seems to have been abandoned in subsequent periods.

The best preserved inlaid object is the Standard of Ur found in one of the royal tombs of this city. It represents two principal scenes on its two sides: a battle and a banquet that probably follows a military victory. The "dairy frieze" found at Tell al-'Ubaid represents, as its name suggests, dairy activities (milking cows, cowsheds, preparing dairy products). It is our source of the most information on this practice in ancient Mesopotamia.

Similar mosaic elements were discovered at Mari, where a mother-of-pearl engraver's workshop was identified, and at Ebla where marble fragments were found from a 3-meter-high panel decorating a room of the royal palace. The scenes of the two sites have strong similarities in their style and themes. In Mari the scenes are military (a parade of prisoners) or religious (a ram's sacrifice). In Ebla, they show a military triumph and mythological animals.

Music

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)