| DUR-KURIGALZU

Dur-Kurigalzu shown within Iraq

The ziggurat of Dur-Kurigalzu in 2010 Location : Baghdad Governorate, Iraq

Region : Mesopotamia

Coordinates : 33°21'13 N 44°12'8 E

Type : tell

Length :

Area : 225 ha (560 acres)

Site notes :

Excavation dates : 1942–1945

Archaeologists : Taha Baqir, S. Lloyd

Dur-Kurigalzu (modern `Aqar-Quf in Baghdad Governorate, Iraq) was a city in southern Mesopotamia, near the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala rivers, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) west of the center of Baghdad. It was founded by a Kassite king of Babylon, Kurigalzu I, some time in the 14th century BC, and was abandoned after the fall of the Kassite dynasty. The prefix Dur- is an Akkadian term meaning "fortress of", while the Kassite royal name Kurigalzu, since it is repeated in the Kassite king list, may have a descriptive meaning as an epithet, such as "herder of the folk (or of the Kassites)". The city contained a ziggurat and temples dedicated to Mesopotamian gods, as well as a royal palace. The ziggurat was unusually well-preserved, standing to a height of about 52 metres (171 ft).

History

:

In Kassite times the area was defined by a large wall that enclosed about 225 hectares (560 acres). The shape of the city is elongated and features several mounds, perhaps reflecting a functional separation of the parts of the site. The hill of Aqar Quf is dominated by the most visible monument at the site, a ziggurat devoted to the main god of the Babylonian pantheon, Enlil. Because of the uniformity of architectural features, the ziggurat and surrounding temple complexes appear to have been founded by the Kassite king, Kurigalzu. The ziggurat measured 69 by 67.6 metres (226 ft × 222 ft) at its base. It was approached by three main staircases leading up to the first terrace, which has been reconstructed by the Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities. The surrounding temple-complex has only been excavated on the south-west side of the ziggurat. The palace area of Tell al-Abyad consists of several stratigraphic architectural layers, which suggests several phases of building in this area over the entire stretch of the Kassite period, and therefore has great potential to yield an invaluable sequence of pottery and other material for the period. Associated tablets confirm that the structure was occupied throughout the Kassite period. The palace has innovative architectural features, being constructed in modules of three rooms around large courts. In addition, excavators also discovered a treasury on the east of the palace and a probable throne room or royal reception/ceremonial chamber.

Ziggurat :

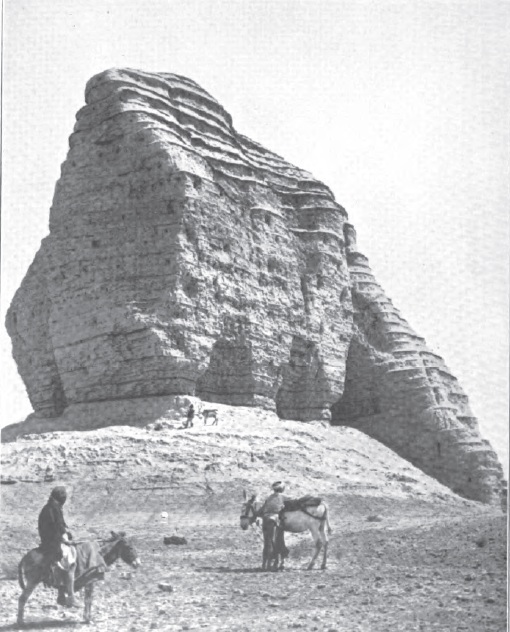

The Ziggurat of Dur-Kurigalzu (1915) The Ziggurat of Dur-Kurigalzu was built in the 14th century BC by the Kassite king Kurigalzu. The core of the structure consists of sun-dried square bricks. Reed mats were placed every seven layers of brick, used for drainage and to assist in holding the bricks together by providing a continuous layer of support. The outer layers of the ziggurat are made from fired bricks. An inscription on one of the fired bricks states that it was laid during the reign of King Kurigalzu II. Today both types of brick, sun-dried and fired, are still made in Iraq in the same fashion and used in farm houses.

The ziggurat at Aqar Quf has been a very visible ancient monument for centuries. For camel caravans and modern road traffic, the ziggurat has served as a signal of the near approach to Baghdad. The site has been one of the favorite places where Baghdadi families have gone to picnic on Fridays, even before it was excavated. A small museum, built in the 1960s, has served to introduce visitors to the site. The structure needs renovation, however.

Because of Aqar Quf's easy accessibility and close proximity to the city of Baghdad, it has been one of Iraq's most visited and best known sites. Its ziggurat has been an outstanding monument for centuries, often confused with the Tower of Babel by Western visitors in the area from the 17th century onwards.

Research

:

Door socket from Dur-Kurikalzu

Male head from Dur-Kurigalzu, Iraq, reign of Marduk-apla-iddina I. Iraq Museum Excavations were conducted from 1942 through 1945, by Taha Baqir and Seton Lloyd in a joint excavation by the Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities and the British School of Archaeology in Iraq. Over 100 cuneiform tablets of the Kassite period were recovered, now in the Iraq Museum.

The excavations included the ziggurat, three temples and part of the palace of Dur Kurigalzu II. The Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities has continued to do some excavation around the ziggurat as part of a restoration project under Saddam Hussein during the 1970s that had reconstructed the lowest stage of the structure. The three excavated areas are the mound of Aqar Quf (including the ziggurat and large temple), a public building (approximately 100 metres (330 ft) to the west), and Tell al-Abyad where a large palace was partially uncovered (about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) to the south-west). The erosion of the ziggurat exposed details of construction that are not readily available in any other temple tower. Thus, it has been a valuable primer for architectural historians. Nowhere else are the layers of reed mats and reed bundles that hold the structure together and offset differential settling as visible as they are here. Many of the currently known major works of art from the Kassite period were found within the palace (located at Tell al-Abyad) at Aqar Quf. Another area within Dur-Kurigalzu, Tell Abu Shijar, was excavated by Iraqi archaeologists and the results have recently been published.

The area of Aqar Quf has potential for future excavations since only small areas within the enclosure wall have been excavated. Especially important is the possibility of a stratigraphic column through all of Kassite times.

Current

status :

The ziggurat suffered damage as a result of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, when the site was abandoned and looted during the security breakdown and chaos that followed the U.S. military's overthrow of Saddam Hussein. Little is left of the modern administration building, museum, event stage and restaurant that once served the picnickers and students who visited the site before the war. Local government officials and the U.S. military charged with security in the area have been working to create a renovation plan. Since mid-2008, local officials have drafted plans to rebuild the historic site, but support from the Iraq Ministry of History and Ruins has not materialized.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |