| NIMRUD

Nimrud shown within Near East

A lamassu at the North West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II before destruction in 2015 Alternative name : Calah, Kalakh, Kalhu

Location : Noomanea, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq

Region : Mesopotamia

Coordinates : 36°05'53 N 43°19'44 E

Type : Settlement

Area : 3.6 km2 (1.4 sq mi)

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located 30 kilometres (20 mi) in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and 5 kilometres (3 mi) south of the village of Selamiyah, in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a major Assyrian city between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC. The city is located in a strategic position 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of the point that the river Tigris meets its tributary the Great Zab. The city covered an area of 360 hectares (890 acres). The ruins of the city were found within one kilometre (1,100 yd) of the modern-day Assyrian village of Noomanea in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq.

The name Nimrud was recorded as the local name by Carsten Niebuhr in the mid-18th century. In the mid 19th century, biblical archaeologists proposed the Biblical name of Kalhu (the Biblical Calah), based on a description of the travels of Nimrod in Genesis 10. Archaeological excavations at the site began in 1845, and were conducted at intervals between then and 1879, and then from 1949 onwards. Many important pieces were discovered, with most being moved to museums in Iraq and abroad. In 2013, the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council funded the "Nimrud Project", directed by Eleanor Robson, whose aims were to write the history of the city in ancient and modern times, to identify and record the dispersal history of artefacts from Nimrud, distributed amongst at least 76 museums worldwide (including 36 in the United States and 13 in the United Kingdom).

In 2015, the terrorist organization Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) announced its intention to destroy the site because of its "un-Islamic" Assyrian nature. In March 2015, the Iraqi government reported that ISIL had used bulldozers to destroy excavated remains of the city. Several videos released by ISIL showed the work in progress. In November 2016 Iraqi forces retook the site, and later visitors also confirmed that around 90% of the excavated portion of city had been completely destroyed. The ruins of Nimrud have remained guarded by Iraqi forces ever since.

Early history :

The Palaces at Nimrud Restored, 1853, imagined by the city's first excavator, Austen Henry Layard, and the architectural historian James Fergusson

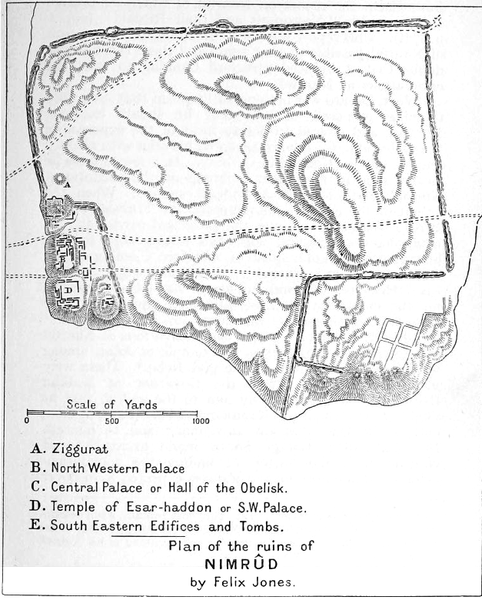

Plan of Nimrud, by Felix Jones bef. 1920 The area excavated in the 19th century is labeled A-E. On the bottom right is Fort Shalmaneser, excavated in the mid-20th century

Foundation :

Capital

of the Empire :

A grand opening ceremony with festivities and an opulent banquet in 879 BC is described in an inscribed stele discovered during archeological excavations. By 800 BC Nimrud had grown to 75,000 inhabitants making it the largest city in the world.

King Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC) continued where his father had left off. At Nimrud he built a palace that far surpassed his father's. It was twice the size and it covered an area of about 5 hectares (12 acres) and included more than 200 rooms. He built the monument known as the Great Ziggurat, and an associated temple.

Nimrud remained the capital of the Assyrian Empire during the reigns of Shamshi-Adad V (822–811 BC), Adad-nirari III (810–782 BC), Queen Semiramis (810–806 BC), Adad-nirari III (806–782 BC), Shalmaneser IV (782–773 BC), Ashur-dan III (772–755 BC), Ashur-nirari V (754–746 BC), Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726–723 BC). Tiglath-Pileser III in particular, conducted major building works in the city, as well as introducing Eastern Aramaic as the lingua franca of the empire, whose dialects still endure among the Christian Assyrians of the region today.

However, in 706 BC Sargon II (722–705 BC) moved the capital of the empire to Dur Sharrukin, and after his death, Sennacherib (705–681 BC) moved it to Nineveh. It remained a major city and a royal residence until the city was largely destroyed during the fall of the Assyrian Empire at the hands of an alliance of former subject peoples, including the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians, and Cimmerians (between 616 BC and 599 BC).

Later

geographical writings :

A similar locality was described in the Middle Ages by a number of Arabic geographers including Yaqut al-Hamawi, Abu'l-Fida and Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, using the name "Athur" near Selamiyah.

Archaeology :

Early writings and debate over name :

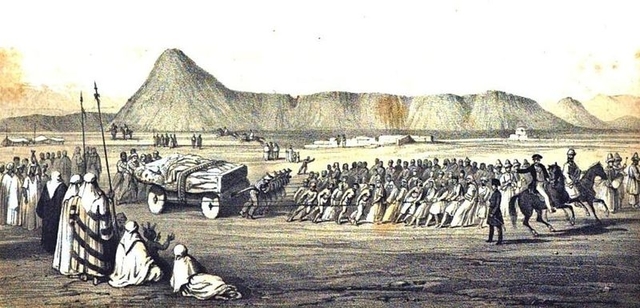

1849 sketch of Layard's expedition transporting a Lamassu

Many of Nineveh's archeological remains were transported to the

major museums of the 19th century, including the British Museum

and the Louvre

In 1830, traveller James Silk Buckingham wrote of "two heaps called Nimrod-Tuppé and Shah-Tuppé... The Nimrod-Tuppé has a tradition attached to it, of a palace having been built there by Nimrod".

However, the name became the cause of significant debate amongst Assyriologists in the mid-nineteenth century, with much of the discussion focusing on the identification of four Biblical cities mentioned in Genesis 10: "From that land he went to Assyria, where he built Nineveh, the city Rehoboth-Ir, Calah and Resen".

Larissa

/ Resen :

The site of Nimrud was visited by William Francis Ainsworth in 1837. Ainsworth, like Rich, identified the site with Larissa of Xenophon's Anabasis, concluding that Nimrud was the Biblical Resen on the basis of Bochart's identification of Larissa with Resen on etymological grounds.

Rehoboth :

The site was subsequently visited by James Phillips Fletcher in 1843. Fletcher instead identified the site with Rehoboth on the basis that the city of Birtha described by Ptolemy and Ammianus Marcellinus has the same etymological meaning as Rehoboth in Hebrew.

Ashur

:

Nineveh

:

Calah

:

Excavations :

A stele in situ at Nimrud Initial excavations at Nimrud were conducted by Austen Henry Layard, working from 1845 to 1847 and from 1849 until 1851. Following Layard's departure, the work was handed over to Hormuzd Rassam in 1853-54 and then William Loftus in 1854–55.

After George Smith briefly worked the site in 1873 and Rassam returned there from 1877 to 1879, Nimrud was left untouched for almost 60 years.

A British School of Archaeology in Iraq team led by Max Mallowan resumed digging at Nimrud in 1949; these excavations resulted in the discovery of the 244 Nimrud Letters. The work continued until 1963 with David Oates becoming director in 1958 followed by Julian Orchard in 1963.

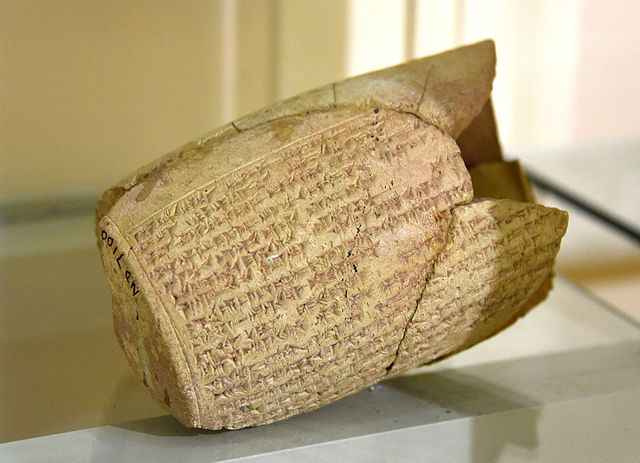

Easarhaddon cylinder from fort Shalmaneser at Nimrud. It was found in the city of Nimrud and was housed in the Iraqi Museum, Baghdad. Erbil Civilization Museum, Iraq Subsequent work was by the Directorate of Antiquities of the Republic of Iraq (1956, 1959–60, 1969–78 and 1982–92), the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw directed by Janusz Meuszynski (1974–76), Paolo Fiorina (1987–89) with the Centro Ricerche Archeologiche e Scavi di Torino who concentrated mainly on Fort Shalmaneser, and John Curtis (1989). In 1974 to his untimely death in 1976 Janusz Meuszynski, the director of the Polish project, with the permission of the Iraqi excavation team, had the whole site documented on film—in slide film and black-and-white print film. Every relief that remained in situ, as well as the fallen, broken pieces that were distributed in the rooms across the site were photographed. Meuszynski also arranged with the architect of his project, Richard P. Sobolewski, to survey the site and record it in plan and in elevation. As a result, the entire relief compositions were reconstructed, taking into account the presumed location of the fragments that were scattered around the world.

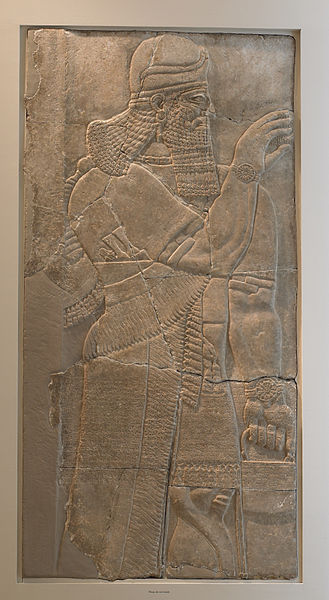

Excavations revealed remarkable bas-reliefs, ivories, and sculptures. A statue of Ashurnasirpal II was found in an excellent state of preservation, as were colossal winged man-headed lions weighing 10 short tons (9.1 t) to 30 short tons (27 t) each guarding the palace entrance. The large number of inscriptions dealing with king Ashurnasirpal II provide more details about him and his reign than are known for any other ruler of this epoch. The palaces of Ashurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III, and Tiglath-Pileser III have been located. Portions of the site have been also been identified as temples to Ninurta and Enlil, a building assigned to Nabu, the god of writing and the arts, and as extensive fortifications.

Remains of the Nabu temple in 2008 In 1988, the Iraqi Department of Antiquities discovered four queens' tombs at the site.

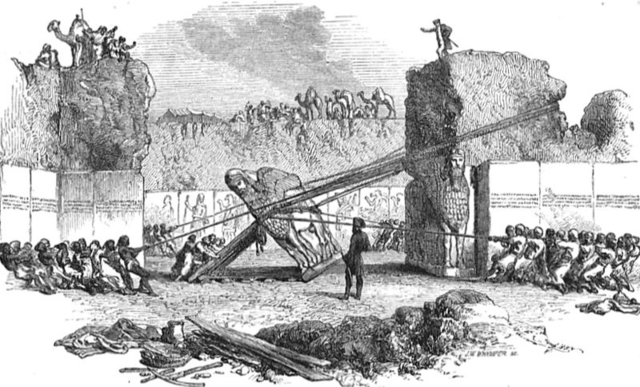

Artworks :

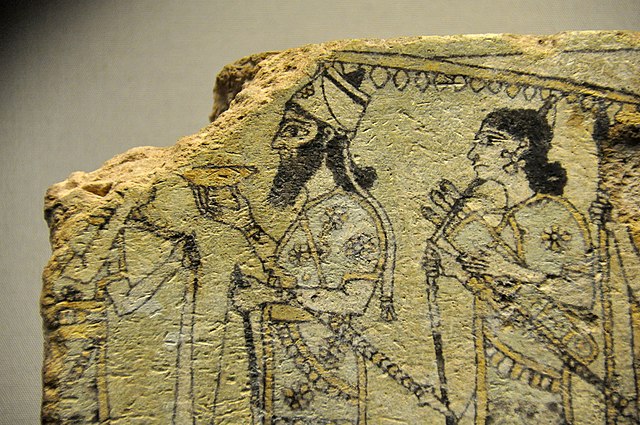

Detail of a glazed terracotta tile from Nimrud, Iraq. The Assyrian king, below a parasol, is surrounded by guards and attendants. 875 – 850 BC. The British Museum Nimrud has been one of the main sources of Assyrian sculpture, including the famous palace reliefs. Layard discovered more than half a dozen pairs of colossal guardian figures guarding palace entrances and doorways. These are lamassu, statues with a male human head, the body of a lion or bull, and wings. They have heads carved in the round, but the body at the side is in relief. They weigh up to 27 tonnes (30 short tons). In 1847 Layard brought two of the colossi weighing 9 tonnes (10 short tons) each including one lion and one bull to London. After 18 months and several near disasters he succeeded in bringing them to the British Museum. This involved loading them onto a wheeled cart. They were lowered with a complex system of pulleys and levers operated by dozens of men. The cart was towed by 300 men. He initially tried to hook up the cart to a team of buffalo and have them haul it. However the buffalo refused to move. Then they were loaded onto a barge which required 600 goatskins and sheepskins to keep it afloat. After arriving in London a ramp was built to haul them up the steps and into the museum on rollers.

Additional 27-tonne (30-short-ton) colossi were transported to Paris from Khorsabad by Paul Emile Botta in 1853. In 1928 Edward Chiera also transported a 36-tonne (40-short-ton) colossus from Khorsabad to Chicago. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has another pair.

Nimrud ivory piece showing a cow suckling a calf The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II, Stela of Shamshi-Adad V and Stela of Ashurnasirpal II are large sculptures with portraits of these monarchs, all secured for the British Museum by Layard and the British archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam. Also in the British Museum is the famous Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, discovered by Layard in 1846. This stands six-and-a-half-feet tall and commemorates with inscriptions and 24 relief panels the king's victorious campaigns of 859–824 BC. It is shaped like a temple tower at the top, ending in three steps.

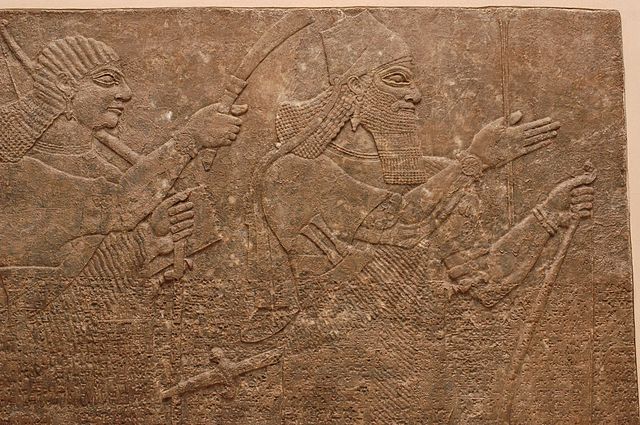

Series of the distinctive Assyrian shallow reliefs were removed from the palaces and sections are now found in several museums (see gallery below), in particular the British Museum. These show scenes of hunting, warfare, ritual and processions. The Nimrud Ivories are a large group of ivory carvings, probably mostly originally decorating furniture and other objects, that had been brought to Nimrud from several parts of the ancient Near East, and were in a palace storeroom and other locations. These are mainly in the British Museum and the National Museum of Iraq, as well as other museums. Another storeroom held the Nimrud Bowls, about 120 large bronze bowls or plates, also imported.

The "Treasure of Nimrud" unearthed in these excavations is a collection of 613 pieces of gold jewelry and precious stones. It has survived the confusions and looting after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 in a bank vault, where it had been put away for 12 years and was "rediscovered" on June 5, 2003.

Significant

inscriptions :

A number of other artifacts considered important to Biblical history were excavated from the site, such as the Nimrud Tablet K.3751 and the Nimrud Slab. The bilingual Assyrian lion weights were important to scholarly deduction of the history of the alphabet.

Destruction :

Archaeological site of Nimrud before destruction, 1:33, UNESCO video

Nimrud's various monuments had faced threats from exposure to the harsh elements of the Iraqi climate. Lack of proper protective roofing meant that the ancient reliefs at the site were susceptible to erosion from wind-blown sand and strong seasonal rains.

In mid-2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) occupied the area surrounding Nimrud. ISIL destroyed other holy sites, including the Mosque of the Prophet Jonah in Mosul. In early 2015, they announced their intention to destroy many ancient artifacts, which they deemed idolatrous or otherwise un-Islamic; they subsequently destroyed thousands of books and manuscripts in Mosul's libraries. In February 2015, ISIL destroyed Akkadian monuments in the Mosul Museum, and on March 5, 2015, Iraq announced that ISIL militants had bulldozed Nimrud and its archaeological site on the basis that they were blasphemous.

A member of ISIL filmed the destruction, declaring, "These ruins that are behind me, they are idols and statues that people in the past used to worship instead of Allah. The Prophet Muhammad took down idols with his bare hands when he went into Mecca. We were ordered by our prophet to take down idols and destroy them, and the companions of the prophet did this after this time, when they conquered countries." ISIL declared an intention to destroy the restored city gates in Nineveh. ISIL went on to do demolition work at the later Parthian ruined city of Hatra. On April 12 2015, an on-line militant video purportedly showed ISIL militants hammering, bulldozing and ultimately using explosive to blow up parts of Nimrud.

Irina Bokova, the director general of UNESCO, stated "deliberate destruction of cultural heritage constitutes a war crime". The president of the Syriac League in Lebanon compared the losses at the site to the destruction of culture by the Mongol Empire. In November 2016, aerial photographs showed the systematic leveling of the Ziggurat by heavy machines. On 13 November 2016, the Iraqi Army recaptured the city from ISIL. The Joint Operations Command stated that it had raised the Iraqi flag above its buildings and also captured the Assyrian village of Numaniya, on the edge of the town. By the time Nimrud was retaken, around 90% of the excavated part of the city had been destroyed entirely. Every major structure had been damaged, the Ziggurat of Nimrud had been flattened, only a few scattered broken walls remained of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II, the Lamassu that once guarded its gates had been smashed and scattered across the landscape.

As of 2020, archaeologists from the Nimrud Rescue Project have carried out two seasons of work at the site, training native Iraqi archaeologists on protecting heritage and helping preserve the remains. Plans for reconstruction and tourism are in the works but will likely not be implemented within the next decade.

Gallery :

Items excavated from Nimrud, located in museums around the world

Nimrud ivory plaque, with original gold leaf and paint, depicting a lion killing a human (British Museum)

Ashurnasirpal II (Louvre)

Ashurnasirpal II (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Assyrian lion hunt (Pergamon)

Lamassu, Stelas, Statue, Relief Panels, including the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (British Museum)

Lamassu of Tiglath-pileser III (British Museum)

City under siege (British Museum)

Cavalry battle (British Museum)

Eagle-headed deity (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Lamassu (Metropolitan Museum)

Relief with Winged Genius (Walters Art Museum)

Two Nimrud ivories made in Egypt (British Museum)

Stela of Shamshi-Adad V, Height 195.2 cm, Width 92.5 cm, (British Museum)

Two archers (Hermitage Museum)

Genius and tree of life (Istanbul Museum)

Tree of life (Brooklyn Museum)

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

___Central_Palace_of_Tiglath-pileser_III_(744-727_B.C)_%2B_Full_Elevation_&_Viewing_South.1.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

,_VIII_sec._ac._02.jpg)

.jpg)