| SIPPAR

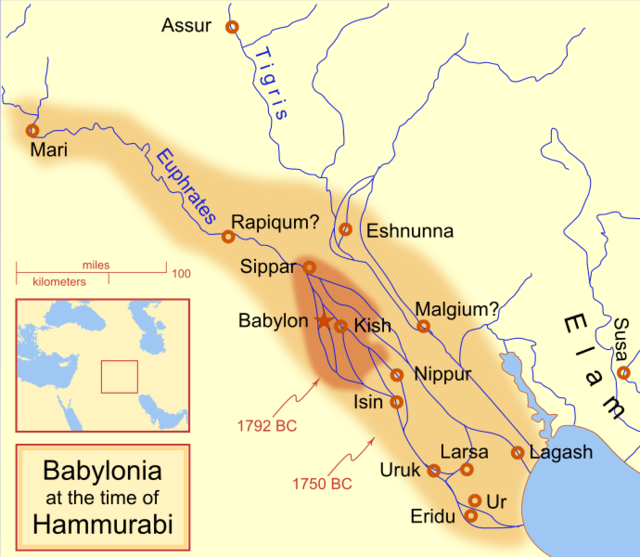

Being close to Babylon, Sippar was an early addition to its empire under Hammurabi Sippar (Sumerian: Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its tell is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, some 60 km north of Babylon and 30 km southwest of Baghdad. The city's ancient name, Sippar, could also refer to its sister city, Sippar-Amnanum (located at the modern site of Tell ed-Der); a more specific designation for the city here referred to as Sippar was Sippar-Yahrurum.

History :

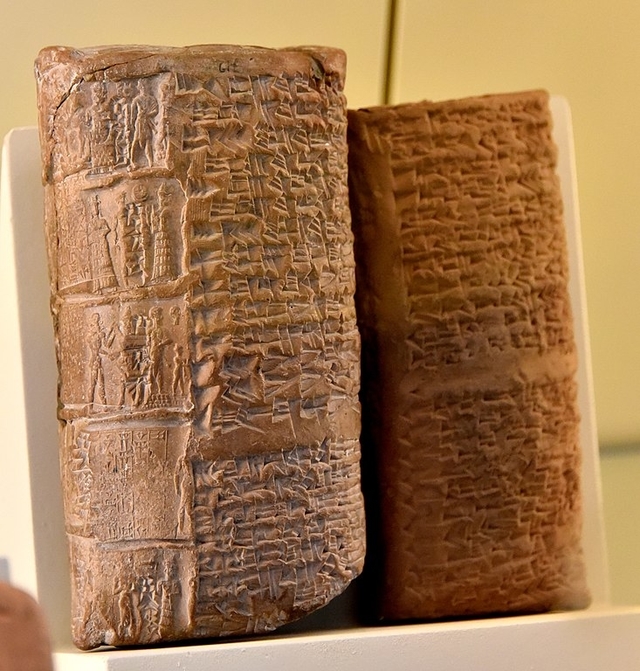

Clay

tablet and its sealed clay envelope. Legal document, listing of

land and their distribution to several sons. From Sippar, Iraq.

Old-Babylonian period. Reign of Sin-Muballit, 1812-1793 BCE. Vorderasiatisches

Museum, Berlin.

While pottery finds indicate that the site of Sippar was in use as early as the Uruk period, substantial occupation occurred only in the Early Dynastic Period of the 3rd millennium BC, the Old Babylonian period of the 2nd millennium BC, and the Neo-Babylonian time of the 1st millennium BC. Lesser levels of use continued into the time of the Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian Empires.

Sippar was the cult site of the sun god (Sumerian Utu, Akkadian Shamash) and the home of his temple E-babbara(means "white house").

During early Babylonian dynasties, Sippar was the production center of wool. The Code of Hammurabi stele was probably erected at Sippar. Shamash was the god of justice, and he is depicted handing authority to the king in the image at the top of the stele. A closely related motif occurs on some cylinder seals of the Old Babylonian period. By the end of the 19th century BC, Sippar was producing some of the finest Old Babylonian cylinder seals.

Sippar has been suggested as the location of the Biblical Sepharvaim in the Old Testament, which alludes to the two parts of the city in its dual form.

Rulers

:

In his 29th year of reign Sumu-la-El of Babylon reported building the city wall of Sippar. Some years later Hammurabi of Babylon reported laying the foundations of the city wall of Sippar in his 23rd year and worked on the wall again in his 43rd year. His successor in Babylon, Samsu-iluna worked on Sippar's wall in his 1st year. The city walls, being typically made of mud bricks, required much attention. Records of Nebuchadnezzar II and Nabonidos record that they repaired the Shamash temple E-babbara.

Classical

speculation :

Pliny (Natural History 6.30.123) mentions a sect of Chaldeans called the Hippareni. It is often assumed that this name refers to Sippar (especially because the other two schools mentioned seem to be named after cities as well: the Orcheni after Uruk, and the Borsippeni after Borsippa), but this is not universally accepted.

Archaeology :

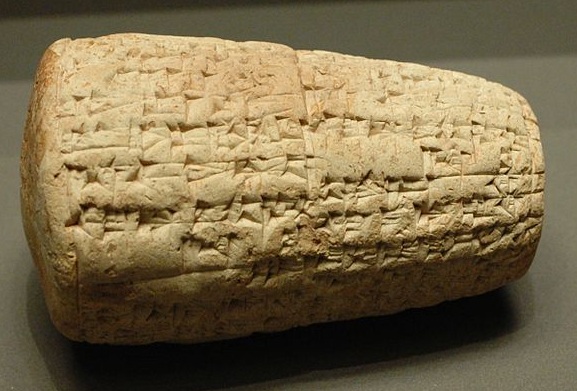

Hammurabi clay cone from Sippar at Louvre

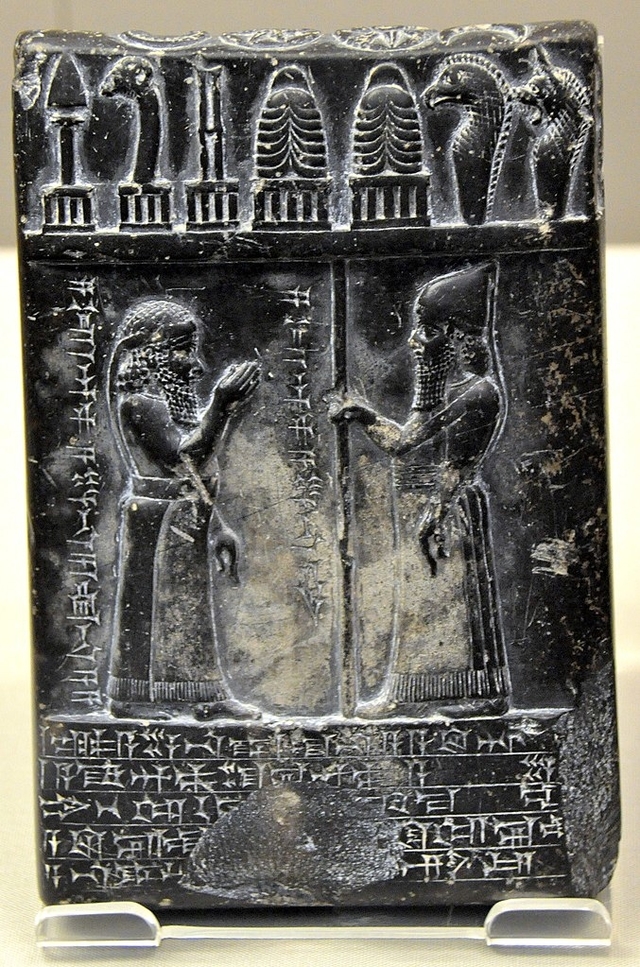

Old Babylonian Cylinder Seal, hematite. The king makes an animal offering to Shamash. The style of this seal suggests that it originated from a workshop in Sippar Tell Abu Habba, measuring over 1 square kilometer was first excavated by Hormuzd Rassam between 1880 and 1881 for the British Museum in a dig that lasted 18 months. Tens of thousands of tablets were recovered including the Tablet of Shamash in the Temple of Shamash/Utu. Most of the tablets were Neo-Babylonian. The temple had been mentioned as early as the 18th year of Samsu-iluna of Babylon, who reported restoring "Ebabbar, the temple of Szamasz in Sippar", along with the city's ziggurat.

The tablets, which ended up in the British Museum, are being studied to this day. As was often the case in the early days of archaeology, excavation records were not made, particularly find spots. This makes it difficult to tell which tablets came from Sippar-Amnanum as opposed to Sippar. Other tablets from Sippar were bought on the open market during that time and ended up at places like the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania. Since the site is relatively close to Baghdad, it was a popular target for illegal excavations.

In 1894, Sippar was worked briefly by Jean-Vincent Scheil. The tablets recovered, mainly Old Babylonian, went to the Istanbul Museum. In modern times, the site was worked by a Belgian team from 1972 to 1973. Iraqi archaeologists from the College of Arts at the University of Baghdad, led by Walid al-Jadir with Farouk al-Rawi, have excavated at Tell Abu Habbah from 1977 through the present in 24 seasons. In the 8th season a library of over 300 tablets was discovered but few have yet been published due to conditions in Iraq. After 2000, they were joined by the German Archaeological Institute. According to Professor Andrew George, a cuneiform tablet containing a portion of the Epic of Gilgamesh probably came from Sippar.

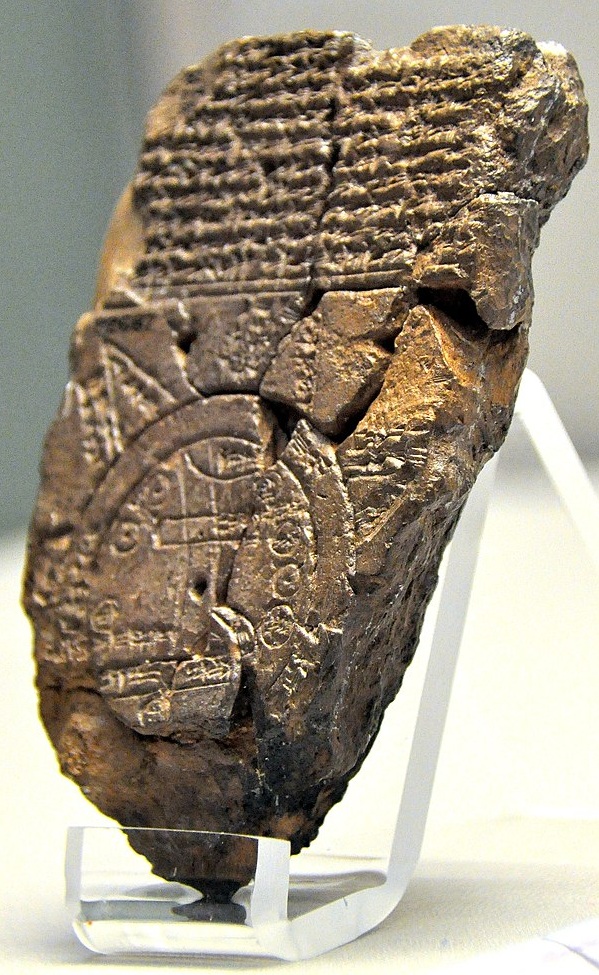

In Sippar was the site where the Babylonian Map of the World was found.

Gallery :

Map of the World from Sippar, Mesopotamia, Iraq. 6th century BCE. The British Museum

Tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina, 9th century BCE, from Sippar, Iraq. British Museum

Detail, Sun God Tablet from Sippar, Iraq, 9th century BCE. British Museum

Detail, Kudurru of Ritti-Marduk, from Sippar, Iraq, 1125 - 1104 BCE. British Museum

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |