CHRONOLOGY

OF THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST

The

chronology of the ancient Near East is a framework of dates for

various events, rulers and dynasties. Historical inscriptions and

texts customarily record events in terms of a succession of officials

or rulers: "in the year X of king Y". Comparing many records

pieces together a relative chronology relating dates in cities over

a wide area. For the first millennium BC, the relative chronology

can be matched to actual calendar years by identifying significant

astronomical events. An inscription from the tenth year of Assyrian

king Ashur-Dan III refers to an eclipse of the sun, and astronomical

calculations among the range of plausible years date the eclipse

to 15 June 763 BC. This can be corroborated by other mentions of

astronomical events, and a secure absolute chronology established,

tying the relative chronologies to the now-dominant Gregorian calendar.

For

the third and second millennia, this correlation is less certain.

A key document is the cuneiform Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa, preserving

record of astronomical observations of Venus during the reign of

the Babylonian king Ammisaduqa, known to be the fourth ruler after

Hammurabi in the relative calendar. In the series, the conjunction

of the rise of Venus with the new moon provides a point of reference,

or rather three points, for the conjunction is a periodic occurrence.

Identifying an Ammisaduqa conjunction with one of these calculated

conjunctions will therefore fix, for example, the accession of Hammurabi

as either 1848, 1792, or 1736 BC, known as the "high"

("long"), "middle", and "short (or low)

chronology".

For

the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC, the following periods can be distinguished

:

| No. |

Particulars |

| 1. |

Early

Bronze Age: A series of rulers and dynasties whose

existence is based mostly on the Sumerian King List

besides some that are attested epigraphically (e.g.

En-me-barage-si). No absolute dates within a certainty

better than a century can be assigned to this period. |

| 2. |

Middle

to Late Bronze Age: Beginning with the Akkadian

Empire around 2300 BC, the chronological evidence

becomes internally more consistent. A good picture

can be drawn of who succeeded whom, and synchronisms

between Mesopotamia, the Levant and the more robust

chronology of Ancient Egypt can be established.

The assignment of absolute dates is a matter of

dispute; the conventional middle chronology fixes

the sack of Babylon at 1595 BC while the short chronology

gives 1531 BC. |

| 3. |

The

Bronze Age collapse: A "Dark Age" begins

with the fall of Babylonian Dynasty III (Kassite)

around 1200 BC, the invasions of the Sea Peoples

and the collapse of the Hittite Empire.

|

| 4. |

Early

Iron Age: Around 900 BC, written records once again

become more numerous with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian

Empire, establishing secure absolute dates. Classical

sources such as the Canon of Ptolemy, the works

of Berossus, and the Hebrew Bible provide chronological

support and synchronisms. An eclipse in 763 BC anchors

the Assyrian list of imperial officials.

|

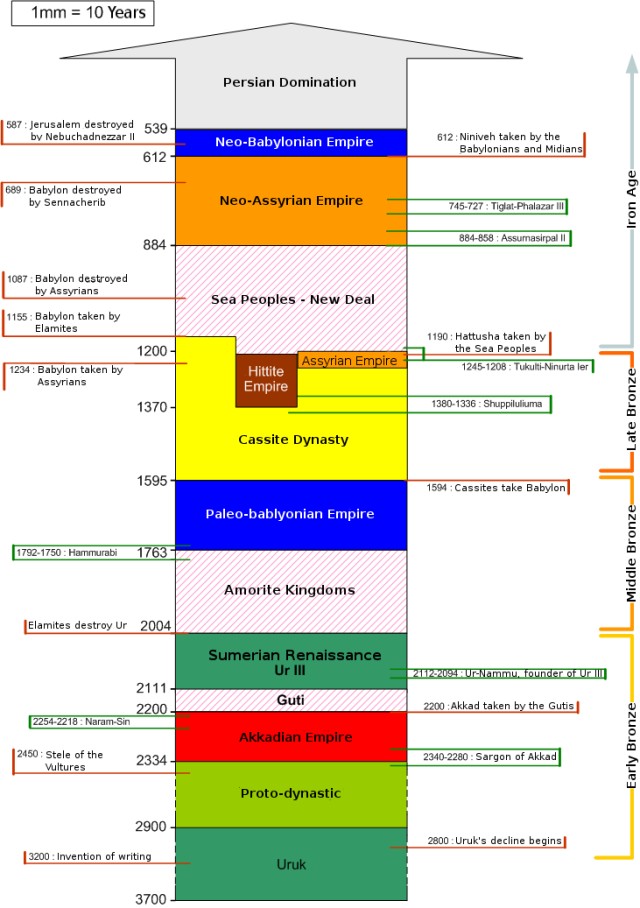

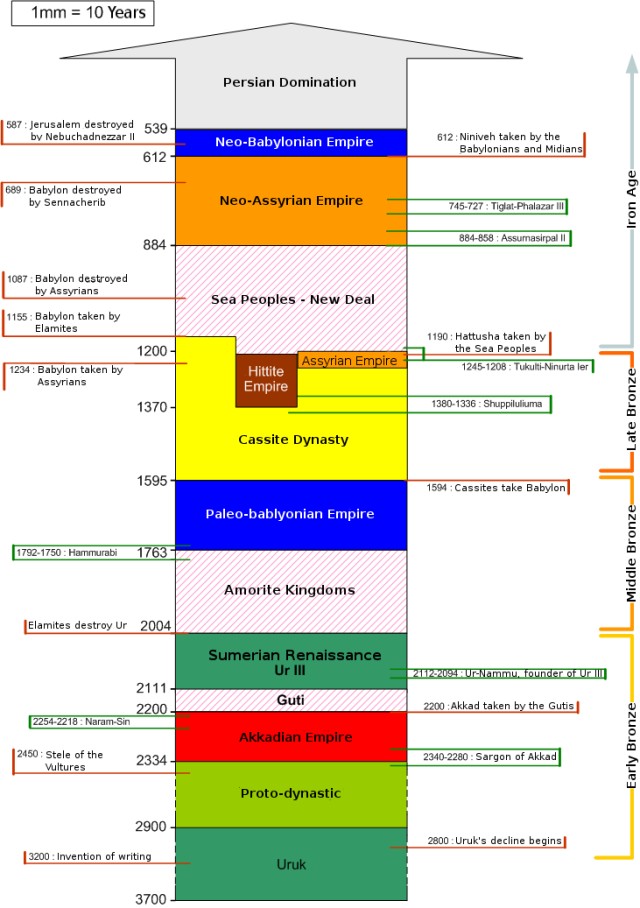

|

Variant

Bronze Age chronologies :

Middle

chronology of the main dominations

Due to the sparsity of sources throughout the "Dark Age",

the history of the Near Eastern Bronze Age down to the end of the

Third Babylonian Dynasty is a floating or relative chronology.

The

major schools of thought on the length of the Dark Age are separated

by 56 or 64 years. This is because the key source for their dates

is the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa and the visibility of Venus has

a 56/64 [clarification needed] year cycle. More recent work by Vahe

Gurzadyan has suggested that the fundamental 8-year cycle of Venus

is a better metric (updated). However, some scholars discount the

validity of the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa entirely. There have

been attempts to anchor the chronology using records of eclipses

and other methods, but they are not yet widely supported. The alternative

major chronologies are defined by the date of the 8th year of the

reign of Ammisaduqa, king of Babylon. This choice then defines the

reign of Hammurabi.

The

"middle chronology" (reign of Hammurabi 1792–1750

BC) is commonly encountered in literature, including many current

textbooks on the archaeology and history of the ancient Near East.

The alternative "short" (or "low") chronology

is less commonly followed, and the "long" (or "high")

and "ultra-short" (or "ultra-low") chronologies

are clear minority views. A recent analysis combining dendrochronology

and radiocarbon dating supported the middle chronology as most likely.

A further refinement by the same group shifted that to the "low-middle

chronology" 8 years lower. As mentioned below, at present there

are no continuous chronologies for the Near East, and a floating

chronology has been developed using trees in Anatolia for the Bronze

and Iron Ages. Until a continuous sequence is developed, the usefulness

of dendrochronology for improving the chronology of the Ancient

Near East is limited. For much of the period in question, middle

chronology dates can be calculated by adding 64 years to the corresponding

short chronology date (e.g. 1728 BC in short chronology corresponds

to 1792 in middle chronology).

The

following table gives an overview of the competing proposals, listing

some key dates and their deviation relative to the short chronology

:

Chronology |

Sumerian

Ruling House |

| Ultra-Low |

Ammisaduqa

Year 8 : 1542 BC

Reign

of Hammurabi : 1696 – 1654 BC

Fall

of Babylon I : 1499 BC

+

- : + 32 a |

| Short

or Low |

Ammisaduqa

Year 8 : 1574 BC

Reign

of Hammurabi : 1728 – 1686 BC

Fall

of Babylon I : 1531 BC

+

- : + 0 a |

| Middle |

Ammisaduqa

Year 8 : 1638 BC

Reign

of Hammurabi : 1792 – 1750 BC

Fall

of Babylon I : 1595 BC

+

- : - 64 a |

| Long

or High |

Ammisaduqa

Year 8 : 1694 BC

Reign

of Hammurabi : 1848 – 1806 BC

Fall

of Babylon I : 1651 BC

+

- : - 120 a |

|

The

chronologies of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Anatolia depend significantly

on the chronology of Ancient Egypt. To the extent that there are

problems in the Egyptian chronology, these issues will be inherited

in chronologies based on synchronisms with Ancient Egypt.

Sources

of chronological data :

Inscriptional :

Thousands of cuneiform tablets have been found in an area running

from Anatolia to Egypt. While many are the ancient equivalent of

grocery receipts, these tablets, along with inscriptions on buildings

and public monuments, provide the major source of chronological

information for the ancient Middle East.

Underlying

issues :

• State of materials :

While there are some relatively pristine display-quality objects,

the vast majority of recovered tables and inscriptions are damaged.

They have been broken with only portions found, intentionally defaced,

and damaged by weather or soil. Many tablets were not even baked

and have to be carefully handled until they can be hardened by heating.

•

Provenance :

The site of an item's recovery is an important piece of information

for archaeologists, which can be compromised by two factors. First,

in ancient times old materials were often reused as building material

or fill, sometimes at a great distance from the original location.

Secondly, looting has disturbed archaeological sites at least back

to Roman times, making the provenance of looted objects difficult

or impossible to determine.

•

Multiple versions :

Key documents like the Sumerian King List were repeatedly copied

over generations, resulting in multiple variant versions of a chronological

source. It can be very hard to determine the authentic version.

•

Translation :

The translation of cuneiform documents is quite difficult, especially

for damaged source material. Additionally, our knowledge of the

underlying languages, like Akkadian and Sumerian, have evolved over

time, so a translation done now may be quite different than one

done in AD 1900: there can be honest disagreement over what a document

says. Worse, the majority of archaeological finds have not yet been

published, much less translated. Those held in private collections

may never be.

•

Political slant :

Many of our important source documents, such as the Assyrian King

List, are the products of government and religious establishments,

with a natural bias in favor of the king or god in charge. A king

may even take credit for a battle or construction project of an

earlier ruler. The Assyrians in particular have a literary tradition

of putting the best possible face on history, a fact the interpreter

must constantly keep in mind.

King

Lists :

Historical lists of rulers were traditional in the ancient Near

East.

•

Sumerian King List :

Covers rulers of Mesopotamia from a time "before the flood"

to the fall of the Isin Dynasty. For many early city-states, it

is the only source of chronological data. However many early rulers

are listed with fantastically long reigns. Some scholars speculate

that this stems from an error in transcribing the original base

60 arithmetic of the Sumerians to the later decimal-based system

of the Akkadians.

•

Babylonian King List :

This list deals only with the rulers of Babylon. It has been found

in two versions, denoted A and B. The later dynasties in the list

document the Kassite and Sealand periods. There is also a Babylonian

King List of the Hellenistic Period in later part of the 1st millennium.

•

Assyrian King List :

Found in multiple differing copies, this tablet lists all the kings

of Assyria and their regnal lengths back into the mists of time,

with the portions with reasonable data beginning around the 14th

century BC. When combined with the various Assyrian chronicles,

the Assyrian King List anchors the chronology of the 1st millennium.

•

Indus Valley King List :

A list of Indus Valley Civilization kings was compiled by Laurence

Waddell, but it is not generally accepted or well regarded by mainstream

academia.

Chronicles

:

Many chronicles have been recovered in the ancient Near East, most

fragmentary; but when combined with other sources, they provide

a rich source of chronological data.

•

Synchronistic Chronicle :

Found in the library of Assurbanipal in Nineveh, it records the

diplomacy of the Assyrian empire with the Babylonian empire. While

useful, the consensus is that this chronicle should not be considered

reliable.

•

Chronicle P :

While quite incomplete, this tablet provides the same type of information

as the Assyrian Synchronistic Chronicle, but from the Babylonian

point of view.

•

Royal Chronicle of Lagash :

The Sumerian King List omits any mention of Lagash, even though

it was clearly a major power during the period covered by the list.

The Royal Chronicle of Lagash appears to be an attempt to remedy

that omission, listing the kings of Lagash in the form of a chronicle.

Some scholars believe the chronicle to be either a parody of the

Sumerian King List or a complete fabrication.

Royal

inscriptions :

Rulers in the ancient Near East liked to take credit for public

works. Temples, buildings and statues are likely to identify their

royal patron. Kings also publicly recorded major deeds such as battles

won, titles acquired, and gods appeased. These are very useful in

tracking the reign of a ruler.

Year

lists :

Unlike current calendars, most ancient calendars were based on the

accession of the current ruler, as in "the 5th year in the

reign of Hammurabi". Each royal year was also given a title

reflecting a deed of the ruler, like "the year Ur was defeated".

The compilation of these years are called date lists.

Eponym

(limmu) lists :

In Assyria, a royal official or limmu was selected in every year

of a king's reign. Many copies of these lists have been found, with

certain ambiguities. There are sometimes too many or few limmu for

the length of a king's reign, and sometimes the different versions

of the eponym list disagree on a limmu, for example in the Mari

Eponym Chronicle. There is now an Assyrian Revised Eponym List which

attempts to resolve some of these issues.

Trade,

diplomatic, and disbursement records :

As often in archaeology, everyday records give the best picture

of a civilization. Cuneiform tablets were constantly moving around

the ancient Near East, offering alliances (sometimes including daughters

for marriage), threatening war, recording shipments of mundane supplies,

or settling accounts receivable. Most were tossed away after use

as one today would discard unwanted receipts, but fortunately for

us, clay tablets are durable enough to survive even when used as

material for wall filler in new construction.

•

Amarna letters :

A key find was a number of cuneiform tablets from Amarna in Egypt,

the city of the pharaoh Akhenaten. Mostly in Akkadian, the diplomatic

language of the time, several of them named foreign rulers including

the kings of Assyria and Babylon. Assuming that the correct kings

have been identified, this locks the chronology of the ancient Near

East to that of Egypt, at least from the middle of the 2nd millennium.

Classical

:

We have some data sources from the classical period :

•

Berossus :

Berossus, a Babylonian astronomer during the Hellenistic period,

wrote a history of Babylon which was lost, but portions were preserved

by other classical writers.

•

Canon of Ptolemy or Canon of Kings :

This book provides a list of kings starting at around 750 BC in

Babylon and forward through the Persian and Roman periods, in an

astronomical context. It is used to help define the chronology of

the 1st millennium.

•

Hebrew Bible :

Not having the stability of buried clay tablets, the records of

the Hebrews have a great deal of ancient editorial work to sift

through when used as a source for chronology. However, the Hebrew

kingdoms lay at the crossroads of Babylon, Assyria, Egypt and the

Hittites, making them spectators and often victims of actions in

the area. Mainly of use in the 1st millennium and with the Assyrian

New Kingdom.

Astronomical

:

• Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa :

A record of the movements of Venus during the reign of a king of

the First Babylonian Dynasty. Using it, various scholars have proposed

dates for the fall of Babylon based on the 56/64-year cycle of Venus.

The mentioned recent work suggesting that the fundamental 8-year

cycle of Venus is a better metric, led to the proposal of an "ultra-low"

chronology.

Eclipses

:

A number of lunar and solar eclipses have been suggested for use

in dating the ancient Near East. Many suffer from the vagueness

of the original tablets in showing that an actual eclipse occurred.

At that point, it becomes a question of using computer models to

show when a given eclipse would have been visible at a site, complicated

by difficulties in modeling the slowing rotation of the earth (T).

One important event is the Nineveh eclipse, found in an Assyrian

limmu list q.e. "Bur-Sagale of Guzana, revolt in the city of

Ashur. In the month Simanu an eclipse of the sun took place."

This eclipse is considered to be solidly dated to 15 June 763 BC.

Another important event is the Ur III Lunar/Solar Eclipse pair in

the reign of Shulgi. Most calculations for dating using eclipses

have assumed the Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa to be a legitimate source.

Dendrochronology

:

Dendrochronology attempts to use the variable growth pattern of

trees, expressed in their rings, to build up a chronological timeline.

At present, there are no continuous chronologies for the Near East.

A floating chronology has been developed using trees in Anatolia

for the Bronze and Iron Ages. Until a continuous sequence is developed,

the usefulness for improving the chronology of the Ancient Near

East is limited. The difficulty in tying the chronology to the modern

day lies primarily in the Roman period, for which few good wood

samples have been found, and many of those turn out to be imported

from outside the Near East.

Radiocarbon

dating :

As in Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean, radiocarbon dates run

one or two centuries earlier than the dates proposed by archaeologists.

It is not at all clear which group is right, if either. Newer accelerator-based

carbon dating techniques may help clear up the issue. Another promising

technique is the dating of lime plaster from structures. Recently,

radiocarbon dates from the final destruction of Ebla have been shown

to definitely favour the middle chronology (with the fall of Babylon

and Aleppo at c. 1595 BC), and seem to discount the ultra-low chronology

(same event at c. 1499 BC), although it is emphasized that this

is not presented as a decisive argument.

Other

emerging technical dating methods include rehydroxylation dating,

luminescence dating, and archeointensity dating (geomagnetic).

Synchronisms

:

Egypt :

At least as far back as the reign of Thutmose I, Egypt took a strong

interest in the ancient Near East. At times they occupied portions

of the region, a favor returned later by the Assyrians. Some key

synchronisms :

| |

Particulars |

• |

Battle

of Kadesh, involving Ramses II of Egypt (in his

5th year of reign) and Muwatalli II of the Hittite

empire. Recorded by both Egyptian and Hittite records. |

• |

Peace

treaty between Ramses II of Egypt (in his 21st year

of reign) and Hattusili III of the Hittites. Recorded

by both Egyptian and Hittite records. |

• |

Amenhotep

III (Amenophis III) marries the daughter of Shuttarna

II of Mitanni. There is also a record of messages

from the pharaoh to Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon

in the Amarna Letter (EA1–5). Other Amarna

letters link Amenhotep III to Burnaburiash II of

Babylon (EA6) and Tushratta of Mitanni (EA17–29)

as well. |

• |

Akhenaten

(Amenhotep IV) married the daughter of Tushratta

of Mitanni (as did his father Amenhotep III), leaving

a number of records. He also corresponded with Burna-Buriash

II of Babylon (EA7–11, 15), and Ashuruballit

I of Assyria (EA15–16) |

|

There

are problems with using Egyptian chronology. Besides some minor

issues of regnal lengths and overlaps, there are three long periods

of poorly documented chaos in the history of ancient Egypt, the

First, Second, and Third Intermediate Periods, whose lengths are

doubtful. This means the Egyptian Chronology actually comprises

three floating chronologies.

Indus

Valley :

There is much evidence that the Harappan civilization of the Indus

Valley traded with the Near East, including clay seals found at

Ur III and in the Persian Gulf. Seals and beads were also found

at the site of Esnunna. In addition, if the land of Meluhha does

indeed refer to the Indus Valley, then there are extensive trade

records ranging from the Akkadian Empire until the Babylonian Dynasty

I.

Thera

and Eastern Mediterranean :

Goods from Greece made their way into the ancient Near East, directly

in Anatolia and via the island of Cyprus in the rest of the region

and Egypt. A Hittite king, Tudhaliya IV, even captured Cyprus as

part of an attempt to enforce a blockade of the Assyrians.

The

eruption of the Thera volcano provides a possible time marker for

the region. A large eruption, it would have sent a plume of ash

directly over Anatolia and filled the sea in the area with floating

pumice. This pumice appeared in Egypt, apparently via trade. Current

excavations in the Levant may also add to the timeline. The exact

date of the volcanic eruption has been the subject of strong debate,

with dates ranging between 1628 and 1520 BC. Radiocarbon dating

has placed it at between 1627 BC and 1600 BC with a 95% degree of

probability. Archaeologist Kevin Walsh, accepting the radiocarbon

dating, suggests a possible date of 1628 and believes this to be

the most debated event in Mediterranean archaeology.

Source

:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Chronology_of_the_ancient_Near_East