| SYRIAN STATES Ancient Syria was much larger than its modern counterpart, being bordered by the Taurus Mountains in the north, the Upper Euphrates to the north-east, and the Syrian Desert to the south-east. The name is Greek, which they used to describe various Assyrian peoples. The relatively few early Syrian states which appeared in the third millennium BC differed somewhat from their contemporaries in Sumer and Akkad. Instead of relying on river irrigation, the agriculture of the north was rain-fed, so yields were lower and larger areas had to be cultivated (although with less labour). As a result, northern cities tended to be smaller with more people living in outlying settlements, and although they were still city states at heart, they had more of an appearance of being small kingdoms.

Amorites began to arrive in the territory to the west of the Euphrates, within modern Syria, from around 2500 BC. The Akkadians called them Amurru, and groups of them drifted down into Sumer where they eventually replaced the Sumerians as rulers in Mesopotamia. Enough groups remained in Syria for their name, Amurru, eventually to be used to refer to part of Syria and all of Phoenicia and the Levant - large areas which contained populations of Amurru - instead of referring to them as a specific kingdom, language, or population.

By the first part of the second millennium BC, most of the Syrian peoples spoke Semitic dialects, but in the northern areas of Syria there is also evidence of non-Semitic Hurrian, a fairly obscure population group. Hurrian names could be found as far south as Nippur, indicating a level of linguistic heterogeneity across the region. Scribal practices were adopted from the south and were apparently taught by Babylonians, which quickly became the most important city state of second millennium Mesopotamia.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from the Columbia Encyclopaedia, Sixth Edition (2010), from the Britannica Concise Encyclopaedia (2010), from Historical Atlas of the Ancient World, 4,000,000 to 500 BC, John Haywood (Barnes & Noble, 2000), from The Ancient Near East, c.3000-330 BC, Amélie Kuhrt (Routledge, 2000, Volumes I & II), from The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History, Colon McEvedy (Penguin Books, 1967, revised 2002), from Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, Michael Road (Facts on File, 2000), from Mesopotamia: Assyrians, Sumerians, Babylonians (Dictionaries of Civilizations 1), Enrico Ascalone (University of California Press, 2007), from The Cambridge Ancient History, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards (Cambridge University Press, 1973), and from A History of the Ancient Near East c.3000-323 BC, Marc van der Mieroop (Blackwell Publishing, 2004, 2007).)

c.10,000 BC :

Alep emerges as one of the world's first inhabited settlements, showing signs of civilisation during the eleventh millennium BC. Areas to the immediate south of the old Aleppo - at Tell al-Ansari and Tell as-Sawda - reveal occupation that can be dated back at least as far as the late third millennium BC.

c.6000 BC :

Ugarit is first founded as a permanent settlement, probably after some centuries (or even millennia) of being used as a seasonal encampment. The erection of a fortified wall at this point shows that the settlement pattern here has changed, and that the site's current occupants have no plans to leave. At some point in the next millennium, Damas is also founded, although it remains unimportant until the tenth century BC.

Four examples of Chalcolithic pottery that has been recovered from archaeological sites in Syria and Anatolia, and which can be dated between 5600-3000 BC c.5000 BC :

Following a slow trend of more permanent occupation across the region, perhaps in the wake of burgeoning early civilisation in Mesopotamia, the settlements site at Alep and Gebal are continuously inhabited from this period onwards.

c.3400 BC :

Alakhtum is first founded as a permanent settlement, located to the west of the larger Syrian state of Yamkhad, about fifty kilometres from the River Orontes. Its fortunes remain largely unknown until the city is re-founded at the beginning of the second millennium BC.

c.3000 BC :

Carchemish, Ebla, and Tuba are first founded as permanent settlements. The first of these has probably been the site of impermanent or failed settlements since as far back as 7000 BC. Ebla and (probably) Tuba are new, although remains of the latter have yet to be discovered, and both start out small to achieve greatness in the mid-to-late third millennium BC.

c.2600 - c.2200 BC :

Although their creation is later than those of Sumer, the early Akkaddian and Amorite city states of the north are less well attested, and many of them are only known from later writings found in Ebla and other places. Those that can be identified by name include Carchemish (already mentioned at 3000 BC), Emar, and Tuttul along the Euphrates, and Arpad, Ebla and Gebal, (both also mentioned above), Hamath, Tuba (again, see 3000 BC), and Ugarit in the west. These states are in contact with each other through diplomatic and commercial means. Some of these centres, such as Ebla and Alep, also seem to be able to impose their will on surrounding states, but details of their military actions are relatively unknown.

c.2200 BC :

The region is disrupted by invasions by barbarians from the north and by the cold, dry period in the Near East which lasts for three hundred years or so. Some cities, such as Ebla, are conquered by Naram-Sin of Agade. He may be taking advantage of the destabilisation, but as this conquest comes around half a century beforehand, he may also be at least a partial cause of it.

By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe It seems more than coincidental that 'barbarians from the north' are causing problems at the same time as the Gutians are first mentioned, possible Indo-European tribes who inhabit the Zagros Mountains. In the same period, Indo-European tribes in the form of the Luwian peoples are settling across southern Anatolia, making it likely that one of these groups is responsible for probing expeditions farther south.

c.2000s BC :

During the flourishing of Ur's third dynasty in Sumer, Syrian states maintain friendly relations with the south. However, following the fall of Ur, the Syrian archaeological record shows a reduction in the number and sizes of settlements in northern Syria for reasons unknown. Documentation on Syria suffers a gap of almost two centuries before the start of the archives at Mari.

It is possible that the region undergoes an economic downturn, with only cities which control the trade routes to the south managing to survive. These include Ebla, Tuttul, and Urshu, and messengers from the Mediterranean city of Gebal also appear. There is no indication of any Syrian city dominating, either militarily or politically. Importantly, there is a strong presence of Amorites in the region by this time, a semi-nomadic people who greatly contribute towards the fall of Ur.

c.1800s BC :

Syria has recovered fully, and a wave of newer small states or fully urbanised cities becomes apparent, including Yadiya in the far north of ancient Syria and Qatna in the western centre. Together they make up a system of kingdoms whose rulers keep large palace archives of diplomatic correspondence showing how vital it is that they remain informed.

c.1809 - 1776 BC :

Areas of Syria are conquered by the short-lived kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia. Following the death of its creator, Shamshi-Adad, in 1776 BC the kingdom swiftly breaks up, with minor kingdoms reasserting themselves throughout the region. Yamkhad remains the dominant force in north-western Syria, controlling a large number of cities such as Alalakh, Carchemish, Ebla, Emar, Hashshu, Tunip, Ugarit, and Urshu. Local rulers are constantly wary of the larger states, Babylon, Elam, or Eshnunna, which can make or break them.

Although Emar's rulers for the seventeenth century BC are unknown, could they have aided Idrimi, son of the king of Alep, in his conquest of Alakhtum from this city? c.1800? BC :

Yahdun-Lim of Mari sends troops to join those of Yamkhad to fight against several hostile Syrian 'states', including Tuttul. The armies of these hostile states are defeated and their towns are attacked.

c.1720 BC :

By now the intensive palace system operated by the high number of states in parts of Syria has become unsustainable. Many cities are abandoned, perhaps due to a combination of popular opposition to the system and changes in rainfall patterns. The historical record for this region disappears.

c.1650 - 1620 BC :

The newly created Hittite kingdom in Anatolia attacks and destroys several Syrian states over several years, and Carchemish and Amurru are among the victims, subsequently falling under Hittite control. Aramaean groups also begin to attempt to infiltrate Syria from this point in time, although they are largely held back by the Mitanni empire. However, they do manage to grab a foothold in Harran.

c.1595 BC :

Mursili's Hittites capture and destroy Alep on their way south to sack Babylon, ending the political situation that had characterised Syria and Mesopotamia for four centuries. States such as Apum, Qatna, Tuttul, and Yamkhad all decline, The region enters a dark age which lasts for up to a century and-a-half in some areas, and the power vacuum allows Hurrians to migrate westwards.

Greater Syrian States :

Following the social collapse of the sixteenth century BC and the resultant minor dark age, some royal houses could be seen to have survived, but they were poor reflections of the past and often had no connection to their famous predecessors. New groups had risen to power elsewhere, such as in Mitanni and Kassite Babylonia, and throughout the region, urbanism was initially at an all-time low since 3000 BC. This new era was characterised as one in which Egypt and the Hittites played major roles in controlling Syria between them, while also maintaining its lack of unity.

In Syria and Canaan, a new generation of more cohesive territorial states arose, while further north and east, many of the older states were now submerged within Mitanni. Alalakh, Emar, and Ugarit all kept larger archives which, along with correspondence from the major states, provides much of the picture for this region during this era. Cities were supported by relatively small hinterlands in which the population was sparse, meaning that labour was in short supply. During the collapse and subsequent dark age after 1200 BC, the newly-arrived Aramaean tribes migrated south into Syria and the upper area of the Levant, where they created states of their own which became increasingly dominant until they were conquered by the Assyrians in the late eighth century. There were still groups of Amorites in the region, though, including those of Bashan, and those who took control on more than one occasion in Moab.

(Additional information from Eden, Bit Adini, and Beth Eden, Alan Millard, from Unger's Bible Dictionary, Merrill F Unger (1957), and from Easton's Bible Dictionary, Matthew George Easton (1897).)

c.1503 BC :

Thutmose

I invades Canaan and Syria, sweeping through much of it and

raising a stele at Carchemish (so far undiscovered by archaeology).

Egypt establishes a presence but does not appear to remain in

force.

c.1478 BC :

A

resurgent Egypt expands rapidly through Palestine and reaches

Mitanni-controlled Syria, making Ugarit a vassal state. The

Egyptians also raid further inland, where local resistance is

supported by Mitanni. Hittite agents are constantly at work,

trying to draw Syrian states over to them, a policy which gradually

sees them gain more influence.

c.1471 BC :

Egypt's Thutmose III campaigns in Syria again, this time sailing along the Palestinian coast rather than marching overland. He captures the port city of Ullaza (just north of modern Tripoli), which belongs to the territory of Tunip, now itself a vassal of Mitanni. On his homeward journey the pharaoh moves inland from Ullaza and captures the city of Ardata.

1453 BC :

Egypt

reasserts its authority in the region by conquering territory

in the Levant and Syria as far north as Amurru. The Egyptians

establish three provinces which are named Amurru (in southern

Syria), Upe (in the northern Levant, which may correspond to

Damas), and Canaan (in the southern Levant, which includes Gebal).

Each one is governed by an Egyptian official. Native dynasts

are allowed to continue their rule over the small states, but

have to provide annual tribute.

c.1370 - 1350 BC :

Suppiluliuma, the new Hittite ruler, takes control of northern Syria from Mitanni. The king of Ugarit informs the Hittites of a planned revolt by Alalakh, so the kingdom is incorporated directly into the empire, with its lands being assigned to Ugarit as a reward, along with those of the territories of Nuhašše (generally to the south of Alep), and Niya (a small and relatively obscure kingdom in northern Syria, also known as Niye, Niy, or Nii). During the same period, the Amarna letters between Egypt and Assyria, and the city states of Canaan and southern Syria, describe the disruptive activities of the habiru, painting them as a threat to the stability of the region.

c.1200 - c.900 BC :

The

Hittite empire falls as general instability grips the region's

Mediterranean coast. Local cities are destroyed by the Sea Peoples

and some, such as Alalakh, Emar, and Ugarit are abandoned completely.

A major regional drought makes the situation worse. Others,

such as Damas and Yadiya, are settled by Aramaean tribes, but

survive only at a much poorer level. The Aramaeans themselves

are new arrivals, only allowed access into northern Syria since

the death of the powerful Assyrian king, Tukulti-Ninurta I,

in 1207 BC. This is also the period in which the Israelite tribes

are supposedly re-colonising areas of Palestine in the south.

The entire region falls into historical obscurity for several

centuries.

c.1150 BC :

Assyria gains a level of control over Syria following the destruction of the Hittite empire.

c.1115 - 1077 BC :

Under Tiglath-Pileser I, Assyria temporarily extends its power to fully include Syria, taking overlordship of the region from Egypt. Assyrian power quickly fades after this, and the region is free once more. This king's campaigns against migrating Aramaean tribes to prevent them settling in northern Mesopotamia and southern Syria ultimately prove fruitless.

The modern site of Tell Halaf was, during its existence, later known as Guzana and it also became the capital of the Aramaean kingdom of Bit-Bahiani, despite Assyrian attempts to prevent Aramaeans from settling in Mesopotamia and southern Syria 870 - 857 BC :

The

Assyrians invade and subjugate Syrian states, including Bit

Adini, Bit Agusi, Carchemish, and Pattin, by which time many

small and semi-obscure cities have arisen, such as Gamgum and

Gan Dunias, along with the kingdom of Kedar in eastern Syria.

Under Hazael, Damas expands its own borders by annexing all the Hebrew possessions east of the Jordan, ravaging Judah, and rendering Israel impotent. The Old Testament's 'kings of Syria' are the Damascenes. From inscriptions by Shalmaneser III of Assyria it appears that Hazael also withstands an attack by the Assyrian army and keeps Damas, Syria, and Philistia independent (although he does seize the city of Gath). However, his actions against his neighbours unleashes a long series of conflicts with Jerusalem. Gath is subsequently besieged and then destroyed, towards the end of the century, and it never recovers.

853 BC :

Assyria fights the Battle of Qarqar against twelve Syrian and Canaanite kings, including those of Ammon, Arvad, Byblos, Damas, Edom, Egypt, Hamath, Kedar, and Samaria. The battle consists of the largest known number of combatants to date, and is the first historical mention of the Arabs from the southern deserts. Despite claims to the contrary, the Assyrians are defeated, since they do not press on to their nearest target, Hamath, and do not resume their attacks on Hamath and Damas for about six years. However, in the same year, Babylonia and the rich area of southern Mesopotamia is taken, as is Gan Dunias.

When the Neo-Assyrian empire threatened the various city states of southern Syria and Canaan around 853 BC, they united to protect their joint territory - successfully it seems, at least for a time c.840 BC :

Under

Hazael, Damas expands its own borders by annexing all the Hebrew

possessions east of the Jordan, ravaging Judah, and rendering

Israel impotent. The Old Testament's 'kings of Syria' are the

Damascenes. From inscriptions by Shalmaneser III of Assyria

it appears that Hazael also withstands an attack by the Assyrian

army and keeps Damas, Syria, and Philistia independent (although

he does seize the city of Gath). However, his actions against

his neighbours unleashes a long series of conflicts with Jerusalem.

760s BC :

Urartu

is victorious against Assyria, and conquers the northern part

of Syria, making Urartu the most powerful state in the post-Hittite

Near East (and this probably serves to distract Assyrian attention

from the smaller Syrian kingships such as Gamgum). However,

Shamshi-ilu, the all-but independent Assyrian king of the west,

does score a victory in battle against Urartu before 745 BC,

as is recorded by a report on inscriptions of stone lions guarding

the gateways at Kar-Shulmanu-Ashared. It makes no mention of

his master, the Assyrian king.

730s & 720s BC :

Led

by Tiglath-Pileser III, Assyria conquers most of Syria and the

Levant, including Carchemish, Damas, Gamgum, Hamath, Samaria,

Judah, Lukhuti, Moab, Pattin, and Phoenicia. In many cases,

local dynasties are removed in favour of Assyrian governors.

Some, such as Moab, appear to keep their native rulers, but

these are now tributary to Assyria.

722 BC :

The Syrians support Mardukapaliddina II in his successful bid to usurp the Babylonian throne.

612 - 605 BC :

Assyria falls and Babylonia gains control of much of its former territory, including Syria, despite an attempt by Egypt to prevent this. Some sources do indeed state that Babylonia inherits control of Syria immediately, but the fact that the city of Damas definitely falls in 572 BC suggests a period of renewed independence or a much looser alliance with the inheritors of the Assyrian empire. It is also possible - although entirely unrecorded - that it and other Syrian cities manage to rebel against initial attempts to control it, necessitating the conquest of 572 BC.

605 - 539 BC :

Babylonia controls increasing amounts of Syria until Nabonidus angers the Babylonians by trying to reintroduce Assyrian culture. Perhaps because of that, resistance to Cyrus the Great of Persia, when he enters Babylonia from the east, is limited to just one major battle, near the confluence of the Diyala and Tigris rivers. On 12/13 October (sources vary), Babylon is occupied by Cyrus, who adopts an enlightened approach to his subjects, and allows the captive Judeans to return home. Syria becomes a Persian satrapy known as Ebir-nari.

Later

Syria :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Syria was added to the Persian empire. Under Persian governance a satrap (governor) was installed to govern it, with a generally peaceful transfer of power (except in Philistine Gezer). Documentation for this period is much worse than for the previous two thousand years of Semitic domination of the region, so even the dates of office for these governors is uncertain. This was not due to poor record-keeping, however, but to the general use of perishable materials such as papyrus. Many records that did exist were destroyed during the Greek takeover of the region in the fourth century BC when many urban centres were re-founded.

Babylonia was the senior great satrapy in the region. The main satrapy of Athura (former Assyria) fell within Babylonia's administrative umbrella and was subservient to it. Thanks to its close association with Babylonia, the name of Athura was used almost synonymously (certainly by Herodotus and Strabo). Babylon's rank during the Achaemenid period (and beyond) and the status of officials who were installed there also suggest that Babylonia was the superior great satrapy. On the occasion of the rebellion of Megabyzus in Syria, the satrap of Babylonia was responsible for its suppression. This alone proves its higher hierarchical rank, as does the fact that Alexander the Great settled matters relating to Assyria in Babylon. It was also Strabo who reported (accurately) that Athura consisted of (old) Assyria along with Khilakku (Cilicia), Syria, and Phoenicia. Therefore Megabyzus and other holders of his office were satraps of all of these, even if they had their own, lesser satraps.

Later Syria seems to have been established as a satrapy in its own right under the name of Ebimari or Ebir-nari (Babylonian) or Abar-Nahra (Aramaic-Persian) - 'beyond the river [Euphrates]'. Once Syria was stripped away from Athura, thereby lessening Babylonia's own importance, the post of Babylonian satrap was poorly attested. Persian freedom laws allowed the cities of the Levant (Phoenicia) to continue to practice their own religions, carry out their own commercial activities, and establish colonies along the Mediterranean coast. Where these are known, the Old Persian names of satraps are shown first, followed by Greek and other interpretations.

As a minor satrapy, Ebir-nari (Syria) included not only Phoenicia but also Cyprus and Palestine, which contained plenty of entities from the Old Testament such as Megiddo, Samaria, and Gilead. The capital is uncertain and may have moved around somewhat, although Damascus was certainly important. The satrapy's northern boundary with Katpatuka (Cappadocia) is only hypothetical, probably following the Taurus ranges to the bend of the Euphrates. Syria's other borders with Athura and Khilakku are well attested. The Cilician border was marked by the Amanus mountain range and the Syrian Gates, while most of the Assyrian border coincided with the course of the Euphrates. Further south the border can only generally be described as following the edge of the Arabian Desert. It may have run immediately to the south of Gaza (offered by Herodotus), but in the late Achaemenid period, after the loss of the province of Arabia and with only a narrow Mediterranean coastal strip securing the connection with Egypt, the southern border may have been fixed at the Nile's Pelusian branch.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from The Cambridge Ancient History, John Boardman, N G L Hammond, D M Lewis, & M Ostwald (Eds), from Alexander the Great, Krzysztof Nawotka (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), from A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith (Ed), and from External Links: University of Leicester, and Listverse, and Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Nabonidus Chronicle, contained within Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles, A K Grayson (Translation, 1975 & 2000, and now available via Livius in an improved version), and Encyclopaedia Iranica, and People in the Bible Confirmed Archaeologically (Bible Archaeology Society).)

539 - 537? BC :

? : Babylonian satrap of Mesopotamia, Ebir-nari, & Phoenicia.

539 BC :

Despite the fall of Babylon itself to the Persians, it is entirely possible that pockets of resistance remain - or at least areas in which Persian overlordship is tacitly acknowledged while local rule is maintained on a semi-independent basis, at least for a time. The Chaldeans who had provided Babylon's last dynasty of kings may be one such case. Although specific details are not recorded, the Book of Daniel seems to retain a memory of this in Belshar-uzur.

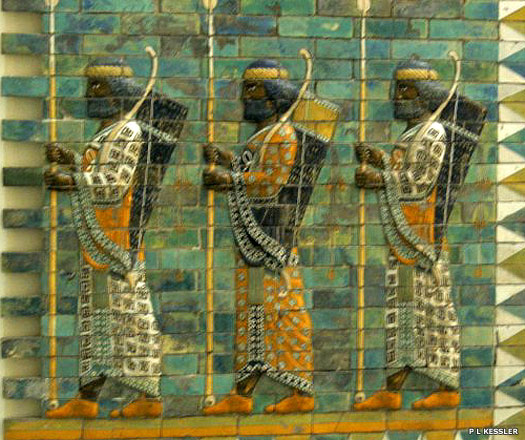

This Achaemenid (Persian empire) palace decoration stood in the city of Babylon and was transported to Berlin upon being rediscovered by archaeologists in the twentieth century fl c.539 BC :

Belshar-uzur / Bel-sarra-Uzur : Son of Nabonidus. The Belshazzar of the Book of Daniel.

539 BC :

Belshar-uzur is the son of Nabonidus and may legitimately claim to be the true successor to the throne even though he holds no power and doesn't have the resources to enforce his claim. He is apparently killed by Cyrus the Great even though his father is allowed to live, so he cannot be the otherwise unknown Babylonian satrap for the first couple of years of Persian rule before being replaced by Gaubaruva. Instead, as Cyrus allows existing offices to be retained at first, this post is probably still filled by its Neo-Babylonian incumbent.

537? - 522 BC :

Gaubaruva / Gobryas / Gobares : Persian satrap of Babylonia (Mesopotamia), Ebir-nari, & Phoenicia.

537? BC :

Gaubaruva is appointed as the first Persian satrap of Babylonia. He is known by a whole host of interpretations of his name, from the Old Persian Gaubaruva or the Akkadian Gubaru, to the Greek Gobryas, and the Latin Gobar(es). He can also be equated with the Cyaxares of the Cyropaedia, but should not be confused with the General Ugbaru (Old Persian) or Gobryas (Greek) who aids Cyrus the Great in the conquest of Mesopotamia (a mistake made in the Grayson version of the Nabonidus Chronicle). Ugbaru may in fact govern the district or province of Gutium for a short time before dying, having already reached an advanced age.

537 - 520 BC :

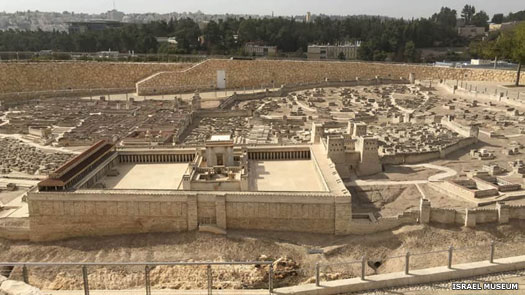

Sheshbazzar is instructed by Cyrus the Great to begin construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, sited over the ruins of the First Temple. He is supplied with the store of gold and silver vessels that Nebuchadnezzar had removed. In 520 BC, Zorobabel (Zerubbabel), Hebrew by birth of the House of David, is commanded to complete the now-stalled work on the temple. His superior would be Tattenai of Ebir-nari.

524? - 516 BC :

Uštani / Ushtanni : Satrap of Babylonia (Mesopotamia), Ebir-nari, & Phoenicia.

fl c.520 - 500 BC :

Tattenai / Tatannu : Syrian sub-satrap. Mentioned in Old Testament's Book of Ezra.

502 BC :

A number of cuneiform tablets bear the name 'Tattenai', having survived as part of what could be a family archive. One tablet in particular links him to Syria and to his mention in the Old Testament, a promissory note dated to the twentieth year of Darius I, which would be 502 BC. It identifies a witness to a transaction as a servant of 'Tattannu, governor of beyond the river [Euphrates]'.

Construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem was begun on the order of Persia's King Cyrus the Great, with the work being under the direct command of his satraps in Judah, Sheshbazzar and Zorobabel c.484 - 482 BC :

Although any records to prove it have not survived, it would seem to be in this period, between about 490-482 BC, in which Ebir-nari is created a satrapy in its own right, removing it from the administration of Babylonia. The cause may well be the revolt in Babylonia which arises shortly after a greater revolt in Egypt. In fact tablets from Babylonia seem to show evidence of two risings by claimants to the Babylonian throne. The first is a minor affair, but the second, in 482 BC, seems more serious.

After that, Xerxes removes 'King of Babylonia' from his own titles and Babylonia is no longer a kingdom, merely a province of the Persian empire. The satraps here show a tendency to be hereditary, in the fashion of many of the posts in Anatolia from around this point onwards, but with less success at forming a single commanding dynasty.

c.480 - 465 BC :

Megabyzus / Baghabuxsha : Satrap. Died 440 BC (aged 76).

465 - c.447 BC :

Megabyzus may hand over the satrapy of Ebir-nari (possibly to his son) to go and deal with the rebellion in Mudraya. Subsequently, the captured Egyptian prince, Inarus, is crucified along with fifty Athenian prisoners by Amestris, the queen mother. Megabyzus had negotiated an armistice with Inarus with promises of safe conduct and he now feels that his honour has been compromised. He returns to Ebir-nari and proceeds to revolt.

As the region's superior - at least until very recently - the satrap of Babylonia is responsible for the suppression of the revolt, but the able Megabyzus routs not one but two expeditions which are sent against him. Both commanders are wounded by him in person (just as Inarus had been), and he himself sustains a wound, all of which apparently satisfies honour and he is reconciled with the Persian king.

? - c.417? BC :

Artyphios : Son. Satrap? Revolted & executed.

c.417 BC :

A few years after securing the throne (probably after 417 BC) Darius II has to contend with a revolt by his full brother, Arsites. The driving force here is Artyphios, son of Megabyzus, possible successor to his father as satrap in Ebir-nari. Darius suffers two reverses before he is finally able to put down the revolt by seducing the Greek mercenaries of Artyphios. Both rebel leaders are put to death.

Construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem was begun on the order of Persia's King Cyrus the Great, with the work being under the direct command of his satraps in Judah, Sheshbazzar and Zorobabel fl 407 & 402 BC :

Belsunu / Bel-shunu / Belesys : Satrap of Athura, Ebir-nari, & Phoenicia.

fl 401 & 387 BC :

Abrocomas : Satrap of Ebir-nari & Phoenicia.

401 BC :

Cyrus, satrap of Asia Minor, attempts to revolt, mobilising an army and ten thousand Greek mercenaries to attack his brother. Defeat leads to his death in October 401 BC at the Battle of Cunaxa. Abrocomas, having been assembling forces for a re-invasion of Egypt, marches to the assistance of Artaxerxes II. He arrives following the battle's conclusion but the extra manpower is no doubt ideal in handling mopping-up operations.

389 - 387 BC :

Abrocomas joins two Persian army commanders - Pharnabazus (not to be confused with Pharnabazus II of Phrygia) and Tithraustes (former satrap of Sparda) - in the attempted reconquest of Egypt. Their efforts meet with little success as the Egyptians have relearned how to defend their country.

fl 351/350 BC :

Belsunu / Bel-shunu / Belesys : Satrap of Ebir-nari & Phoenicia.

346 BC :

In tandem with Satrap Mazaeus of Khilakku, Belsunu leads fresh contingents of Greek mercenaries to put down the revolt in the Levant. Phoenicia is attacked first, but both satraps are repulsed. The Persian king himself is forced to follow up with a more direct intervention.

It is known that Mazaeus is issuing coins in Sidon as satrap of Ebir-nari during his time in office (353-333 BC), which makes problematical the assignment here of Belsunu (not to mention Arsames, below). However, Mazaeus could be acting as the senior satrap, overseeing both Belsunu and Ebir-nari, perhaps distantly at first, and more directly later. Arsames could be a short term replacement in 333 BC alone.

? - 333 BC :

Arsames : Satrap of Athura, Ebir-nari, Khilakku & Phoenicia. Killed.

334 - 330 BC :

In 334 BC Alexander of Macedon launches his campaign into the Persian empire by crossing the Dardanelles. The first battle is fought on the River Graneikos (Granicus), eighty kilometres (fifty miles) to the east. Much of Anatolia falls by 333 BC and Alexander proceeds into Syria during 333-332 BC to receive the submission of Ebir-nari, which also gains him Harran, Judah, and Phoenicia (principally Byblos and Sidon, with Tyre holding out until it can be taken by force).

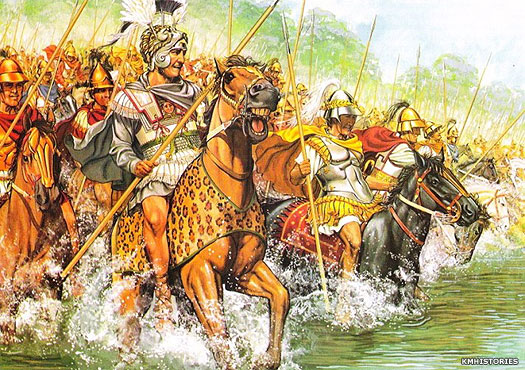

Alexander the Great crossed the River Graneikos (or Granicus) in 334 BC to spark a direct face-off with the Persians that had been brewing for generations, and his victory in battle near the river sent shockwaves through the Persian empire Athura, Gaza, and Egypt also capitulate (not without a struggle in Gaza's case). Mazaeus of Athura initially plays his part by opposing Alexander, but he eventually surrenders, and Alexander makes him satrap of Mesopotamia before going on to seize Babylon and Susa and, having gathered intelligence on Persis, he soon captures that too. Most administrative posts are retained under the Greek empire, including some of those in Mesopotamia.

Argead Dynasty in Abarnahara (Coele Syria) :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Abarnahara was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 301 BC.

Later Syria seems to have been established by the Achaemenid Persians as a satrapy in its own right under the name of Ebimari or Ebir-nari (Babylonian) or Abar-Nahra (Aramaic-Persian) - 'beyond the river [Euphrates]'. As a minor satrapy, Syria included not only Phoenicia but also Cyprus and Palestine, which contained plenty of entities from the Old Testament such as Megiddo, Samaria, and Gilead. The capital is uncertain and may have moved around somewhat, although Damascus was certainly important. The satrapy's northern boundary with Cappadocia is only hypothetical, probably following the Taurus ranges to the bend of the Euphrates. Syria's other borders with Athura (former Assyria) and Cilicia are well attested. The Cilician border was marked by the Amanus mountain range and the Syrian Gates, while most of the Assyrian border coincided with the course of the Euphrates. Further south the border can only generally be described as following the edge of the Arabian Desert. By Alexander's time it may have been fixed at the Nile's Pelusian branch, but Coele Syria may from the beginning (the winter of 333/332 BC) have been divided in two, with a north and south that each had its own satrap.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from The Cambridge Ancient History, John Boardman, N G L Hammond, D M Lewis, & M Ostwald (Eds), from Alexander the Great, Krzysztof Nawotka (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, and from External Links: University of Leicester, and Listverse, and Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Nabonidus Chronicle, contained within Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles, A K Grayson (Translation, 1975 & 2000, and now available via Livius in an improved version), and Encyclopaedia Iranica, and The Government of Syria under Alexander the Great, A B Bosworth (The Classical Quarterly Vol 24, No 1, May, 1974, pp 46-64, Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association (available at JSTOR)).)

332 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

333/332 BC :

In the winter following his capture of Syria, Alexander the Great appoints Menon, son of Cerdimmas, to the satrapy of Coele Syria. He is assigned allied cavalry for the defence of the region while Alexander proceeds into Phoenicia to undertake the sieges of Tyre and Gaza before entering Egypt.

The route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns are shown in this map, with them leading him from Europe to Egypt, into Persia, and across the vastness of eastern Iran as far as the Pamir mountain range 333 - ? BC :

Menon : Greek satrap of Coele Syria. In the north only?

333/332 BC :

Parmenion, Alexander's commander of the successful Phrygian campaign, also remains in Syria, possibly to continue to secure the south before he joins the siege of Tyre in summer 332. Andromachus is his successor in Syria. While both appointments may be in a military role rather than as satrap, it cannot be ruled out that they are effectively satraps of southern Syria which is still unpacified. These uncertain, potentially southern, satraps are shown in green to differentiate them.

333 - 332 BC :

Parmenion : Greek satrap of Coele Syria (in the south only)?

332 - 331 BC :

Andromachus

: Greek satrap of Coele Syria (in the south only)?

Killed.

? - 331 BC :

Arimmas : Greek satrap of Coele Syria (north?). Removed by Alexander.

331 BC :

By late summer 331 BC it is Arimmas who commands in Coele Syria (perhaps only in the north?). On his way back from Egypt and before he crosses the Euphrates, Alexander deposes this satrap and replaces him with Asclepiodorus, son of Eunicus. Andromachus has been captured and burned alive by the Samaritans who have to be punished by Alexander.

Clearly events have been moving swiftly in Syria, with Menon having disappeared without any surviving record to show it, and his incompetent or dangerous successor needing to be removed. As for the late Andromachus, he is replaced by a certain Memnon who is probably the same figure as the Menon of 333 BC.

331 BC :

Asclepiodorus : Greek satrap of Coele Syria. In the north only?

331 BC :

Memnon (Menon?) :

Greek satrap of Coele Syria (in the south only)?

331 BC :

With the Samaritan insurgency dealt with, Syria seems to be securely under Macedonian Greek control. It would seem that the region can no longer justify two commanders, especially with the one in the south appearing to be a military appointment rather than an administrative one. From around this point onwards Syria seems to revert to a single satrapal territory with only one incumbent.

Alexander defeated the Persian king Darius III at the Battle of Gaugamela in Mesopotamia in 331 BC The post is given to Menes at the end of 331 BC who also commands a rather vast swathe of neighbouring territory. Asclepiodorus and Memnon (presumably the same Menon of 333 BC, not named in this instance but with a certain Bessus incorporated by mistake in his place in the records) are responsible for delivering in person the results of the recruitment drive to Alexander by 329 BC, when he is in Zariaspa in Bactria. Menon (if not Memnon) is satrap of Arachosia and Gedrosia by 330 BC.

331 - 323? BC :

Menes : Greek satrap of Athura, Cilicia, Phoenicia, & Syria.

329 BC :

The appointment of Menes (probably the son of Dionysius who had been raised to the circle of Alexander's 'Bodyguards' in 333 BC - a major distinction which would mark him out as a commanding figure) in such a satrapal role over so much territory has been called into question by scholars. He has even been labelled as nothing more than a communications officer despite scholars linking him the the 'Bodyguards' role.

? : Unnamed deputy or stand-in?

329 - 328? BC :

Either way, Menes is not in direct command of Syria in 329 BC, but around 332 BC the satrap of Cilicia, Balacrus, is killed in battle and Menes may be required there as well as in Syria as a matter of urgent expediency, while Alexander's crossing of the Euphrates is imminent. The fact that Menes is also in Zariaspa in Bactria in 329 BC with his own levy of troops makes it clear that his appointment is largely to retain peaceful control without launching any unnecessary offensives against remaining pockets of Persian resistance while raising as many recruits as possible for Alexander's drive eastwards. However, records regarding Syria now fall silent until the death of Alexander, so Menes may well retain his position until then once he has returned from Bactria.

323 - 319 BC :

Laomedon of Mitylene : Greek satrap of Syria & Phoenicia. Unseated.

320 - 319 BC :

Laomedon has been confirmed in his position during the second partition of Alexander's empire in 321 BC in the middle of the First War of the Diadochi, while Cilicia has been separated as a satrapy in its own right. But Ptolemy of Egypt soon begins taking an interest, offering him a large bribe to hand over his satrapy. When Laomedon declines his offer, Ptolemy sends an army under the command of Nicanor to take it by force by 318 BC.

Shown here is an Hellenic-era Egyptian coin which displays the head of Ptolemy I, Greek founder of Egypt's Ptolemaic dynasty following the death of Alexander the Great Laomedon has little with which to resist so he is taken prisoner, escapes, and seemingly joins the general opposition to the Antigonids. His final fate is unknown while Antigonus governs Syria during the period of the remaining Wars of the Diadochi.

318 - 313 BC :

Ptolemy : Greek ruler of Egypt. Evacuated.

319 - 301 BC :

The domination of Syria and Phoenicia by Ptolemy of Egypt briefly comes to an end in 313 BC when he joins the widespread opposition to the Antigonids. In 312 BC Seleucus Nicator defeats Demetrius, son of Antigonus, at the Battle of Gaza which briefly allows Ptolemy to reoccupy Coele Syria. Following a reversal in battle fortunes he pulls out again as Antigonus invades Syria in strength to occupy it.

312 BC :

Ptolemy : Greek ruler of Egypt. Briefly retook the region.

312 - 301 BC :

Antigonus Monophthalmus (One Eye) : Greek ruler of Lycia. Commanded through conquest.

301 - 63 BC :

Much of Syria is gained by the Hellenic Seleucid empire following the decisive Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, although Seleucus allows Ptolemy to retain Coele Syria. Seleucus had already declared himself king of Syria and Babylonia in 305 BC, immediately founding the city of Seleucia in Mesopotamia by massively rebuilding and expanding an existing settlement. Now he also founds the city of Antioch on the Orontes (Syrian Antioch). Over the years, the Seleucids go to war against Ptolemaic Egypt over the rest of Syria, with full possession finally being gained at the end of the Fifth Syrian War in 195 BC.

In time, though, crushed out of existence by the Romans on one side and the Parthians on the other, the Seleucid empire is terminated by 63 BC. Antiochus XIII, the last Seleucid ruler of any kind, is dethroned by Pompey when he turns Syria into a Roman province. Antioch on the Orontes (Syrian Antioch) continues to be an important city throughout the subsequent Roman period, and serves as a major centre of early Christianity.

AD 256 :

The Sassanids capture the Roman fortress city of Dura in eastern Syria. Part of their efforts to take the fortress involves digging a deep mine under the city wall and a tower. The Romans tunnel from the other side to intercept them and a shaft is created around the intercept point. The precise outcome is unknown.

The city of Dura-Europos had been founded in 300 BC by the Seleucid Greeks, seized by the Arsacids and then by the Romans, and was then destroyed almost six hundred years after its creation by a drawn-out border conflict between Rome and the Sassanids In the early 1900s, archaeologist Robert du Mesnil du Buisson discovers a pile of nineteen Roman bodies in the mines. Only one Sassanid body is nearby. In 2009 Simon James of the University of Leicester theorises that the Sassanids hear the Romans in their counter-digging and ignite a fire to meet them. The Romans open the shaft between the two mines, possibly to vent the smoke. Sulphur and bitumen is discovered in the mine, possibly making the Roman bodies the earliest victims of chemical warfare to be discovered.

James believes that the Sassanid deliberately throw these chemicals onto the fire to create deadly fumes, which become sulphuric acid in the lungs of their enemies. The one dead Sassanid soldier is probably the fire's starter and is unable to get out in time. Once the smoke clears, the Sassanids quickly pile the bodies like a shield into the countermine and destroy it. Their mining efforts do not collapse the walls, but the Sassanids eventually get in anyway. They kill some of the residents and deport the rest to Persia. The Seleucid-founded Dura is abandoned forever.

In AD 395 the Roman empire is partitioned. Syria is part of the Eastern Roman empire. Damascus follows the general Syrian sequence of events, but it becomes part of the Nabataean kingdom in the first century AD. In 638-640 Syria is conquered by Islam, and becomes part of the empire and with its own governors of Syria.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |