| BACTRIA Incorporating the Balhikas

A Bronze Age culture emerged in Central Asia around 2200-1700 BC, at the same time as city states were beginning to flourish in Anatolia. It was known as the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, or Oxus civilisation, and Indo-European tribes soon integrated into it. Probably these very same people were very shortly to be found entering India, and those who remained behind appear to enter the historical record in around the sixth century BC, when they came up against the rapidly expanding Persian empire.

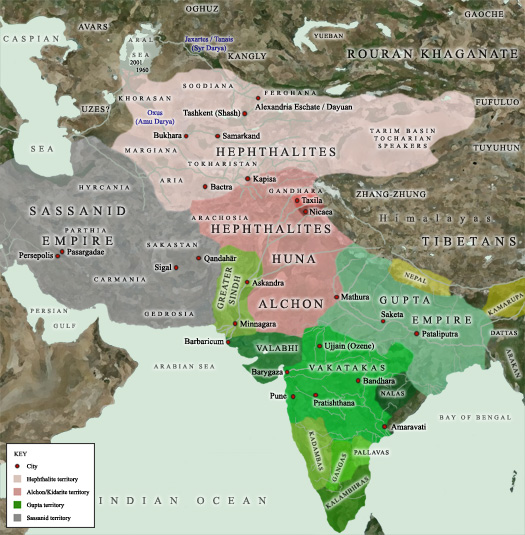

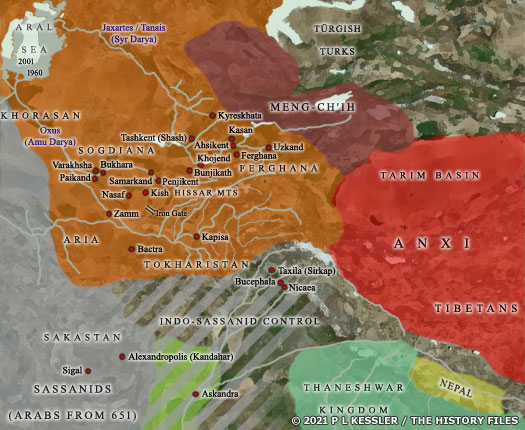

The ancient province of Bactria was located to the far north-east of Persia. Prior to its late sixth century BC domination by the Achaemenid Persians, Bactria seems to have formed part of a much larger and more poorly-defined region known as Ariana, of which the later province of Aria was the heartland. Barely recorded by written history, its precise boundaries are impossible to pin down. It may have encompassed much or all of Transoxiana, the region around the River Oxus (the Amu Darya), and could have reached as far south as the coastline of the Arabian Sea.

Known as Bhalika in Arabic and Indian languages, the territory which formed it lay between the mountains of the Hindu Kush to the south-east and the River Oxus in the north, and at times formed part of the later Islamic region of Khorasan. Bactria was neighboured to the south by Paropamisadae, to the west by Aria and Margiana, and to the north by Sogdiana and Ferghana, with the Pamirs lying between it and the north-western edge of the Himalayas. Today its territory forms parts of northern Afghanistan, western Tajikistan, southern Uzbekistan, and eastern Turkmenistan, and the name survives in the Afghan province of Balkh. In its time it became famous for its warriors and for being the birthplace of Zarathusta, the founder of Zoroastrianism.

The Balhikas are one of the border tribes in the ancient Indian texts, Atharved, along with the Gandhar, both outlying groups (as far as Indo-Aryan settlement is concerned) which were useful as retreats for the fever-stricken.

(Additional information from The Marshals of Alexander's Empire, Waldemar Heckel, and from Alexander the Great and Hernán Cortés: Ambiguous Legacies of Leadership, Justin D Lyons.)

c.2200 - 2000 BC :

An indigenous Bronze Age culture emerges in Central Asia between modern Turkmenistan and down towards the Oxus, the somewhat nebulous region known as Transoxiana. It is known as the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, or Oxus Civilisation (centred on the later provinces of Bactria and Margiana). Indo-European tribes who have not taken part in the exodus to the west or south soon integrate themselves into it.

This king's tomb in the Indo-European settlement in the Karakum (modern Turkmenistan) contains a valuable horse to accompany him into the afterlife 2000 - 1700 BC :

Climate change from around 2000 BC onwards greatly affects this civilisation, denuding it of water as the rains decline. The people are forced to migrate away, abandoning many of their cities. Indo-Iranian groups become dominant here, and over time some of their descendants enter Iran to found states such as that of the Mannaeans, the Median empire, and early Persia. Some go even farther even earlier to form the Mitanni empire. Others cross the rivers of modern Afghanistan and the Hindu Kush mountains and enter India between 1700-1500 BC. They eventually form their own kingdoms there such as Magadh, plus Kaling, and the Kaurav state.

Kingdom of Turan (Indo-Iranian) :

Later myth ascribed a dynasty of Indo-Iranian rulers to this period, as described in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), a poetic opus which was written about AD 1000 but which accessed older works (such as the semi-official seventh century AD book called the Ḵwadāy-nāmag), and perhaps elements of an oral tradition. The Kayanian dynasty of kings of the Persians were also the heroes of the Avesta, which forms the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism. This faith itself had been founded along the banks of the River Oxus, the great river which had probably also formed part of the migratory route used by the Indo-European Persians as they entered Iran.

The earliest of these mythical Indo-Iranian rulers was Fereydun, king of a 'world empire'. His subjects were the Indo-Iranian tribes of the region while his kingdom was apparently in the land of Tūr (or Turaj, sometimes also shown without the accented 'u' as Tur). This can be equated to territory in the heartland of Indo-Iranian southern Central Asia and South Asia, focused mainly on the later provinces of Bactria and Margiana, along with the Kopet Dag region (a mountain range which serves to separate modern Turkmenistan and Iran), the Atrek valley (which supplies an easy route into eastern Iran and is a weak point in the country's defensive line), and the eastern Alborz Mountains (stretching from modern Azerbaijan, along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea, and into Hyrcania and the edges of eastern Iran).

Judging by those borders, the land of Tūr stretched from Samarkand to Tehran, although the kingdom of Turan was probably a good deal smaller and more eastern-based (note the similarly between 'Turan' and Tehran'). The Persians themselves may still have controlled a good deal of the western section as they began to settle in southern Iran. Curiously (and probably not coincidentally), these borders would have placed it on the northern border of another ancient region, that of Ariana. The land of Aryana Vaejah mentioned in the Avesta is usually located to the north and west of both lands.

Fereydun became the father of three sons; Tūr, Salm, and Iraj. Tūr murdered Iraj, thereby triggering an unending feud between the two lines of their descendants. One of Tūr's descendants (possibly a seven-times grandson) was Afrasaib, who ruled the kingdom of Turan during the lifetime of the Persian Kai Kavoos of the seventh century. The stories regarding Turan show it to be in competition with the Persians for mastery of the eastern lands, with many battles being fought. Ultimately it is the Persians who emerge victorious, although the Shahnameh may be showing some bias - history is written by the victorious, after all. Turan's kings are shown with a shaded pink background to denote their legendary status.

(Additional information from Central Asia: A Historical Overview, Edward A Allworth (Duke University Press, 1994), from The Paths of History, I M Diakonoff (Cambridge University Press, 1999), from Islamic Reference Desk, Emeri 'van' Donzel (Brill Academic Publishers, 1994), from Farāmarz, the Sistāni Hero: Texts and Traditions of the Farāmarznāme and the Persian Epic Cycle, Marjolijn van Zutphen, and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Iranians & Turanians in the Avesta.)

Fereydun / Faridun / Fareidun : Ruled a 'world empire'. Abdicated in favour of Manuchehr.

Tūr : Son of Fereydun. Gifted Central Asia. Killed Iraj of Persia.

Thanks to the murder of Iraj by Tūr and Salm, the Persians retaliate under the command of Iraj's grandson, Manuchehr. One of the leading warriors under his command may be Garshāsp (possibly also known as Karāsp), a figure of the Shahnameh or Shahnama, the Book of Kings and a possible descendant of the mythical Indo-Iranian King Jamshid. Tūr and Salm cross the Oxus to face Manuchehr's army on the border between Iran and Turan. The ensuing battle results in heavy casualties for the Turanians, and Tūr is afterwards ambushed and beheaded. Salm is later captured and also beheaded.

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) Pashang : Grandson. Continued the war against the Persians.

7th cent BC :

Afrasiab : Son. Defeated and died.

The story of Afrasiab's eventual defeat and death comes largely from the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings). He is repeatedly defeated by Kai Khosrow (his own grandson via his daughter, Farangis). Forced out of his own lands he wanders wretchedly, taking refuge in a cave known as the Hang-e Afrasiab (meaning the 'dying place of Afrasiab'), on a mountain in Azerbaijan. Ultimately, he is killed by the divine plant of Zoroastrianism, Haoma, near the Čīčhast (location uncertain, but proposed as Lake Hamun in Sistan, which contradicts his location in Azerbaijan). He meets his death in the cave.

7th cent BC :

Sijavus / Siyavash : Son of Kai Kavoos of Persia, and son-in-law of Afrasiab. Sijavus is a legendary Persian prince and the son-in-law of the mythical Afrasiab, the hero and king of Turan. Due to the treachery of his stepmother, Sudabeh, Sijavus exiles himself to Turan (presumably well before the defeat and death of Afrasiab). There, he marries Farangis, Afrasiab's daughter, but the king later orders Sijavus to be killed. His death is avenged by his son, the very same Kai Khosrow mentioned above, who inherits the early Persian throne.

c.546 - 540 BC :

The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea). Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhar, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse. The inference is very clear - whatever control of Turan the Persians had enjoyed following the death of Afrasiab, it did not last and the lands now have to be conquered properly.

Persian

Satraps of Bakhtrish (Bactria) :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Bactria was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was populated by Indo-Iranian tribal groups, and especially by the region's largest Indo-Iranian tribe, known as the Balhikas. Under the Persians it was formed into an official great satrapy or province which, according to the Behistun inscription of Darius the Great, was called Bakhtrish (Bāxtri - Bactria is a Greek mangling of the name). Its capital was Bactra, seemingly using the same name as the tribe itself, although more likely it was a variation. An alternative name for it was Zariaspa, on the site of modern Balkh.

These eastern regions of the new-found empire were ancestral homelands for the Persians. They formed the Indo-Iranian melting pot from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

The appointed satraps were usually Achaemenid princes or members of the highest social elite, with Bessus being the best-known example. Information about the satrapy's administration comes predominantly from the time of Alexander's campaign. The minor satrapy of Mergu was also under the oversight of the satrap of Bakhtrish, as apparently was much of the Central Asian region, as proven by the Behistun inscription. The southern border with the province of Gadar was formed by the Hindu Kush, which today still marks the frontier of numerous Afghan provinces. To the north the River Oxus (Amu Darya) marked the frontier with Suguda (Sogdiana), but the borders can only roughly be estimated where they met Haraiva to the south-west, Mergu to the west, and the minor satrapy of the Dyrbaeans to the east.

The Barcanians were Greek members of the former colonial city of Barce in Cyrenaica. The Greeks were always troublesome for the Persians to govern, and around 515 BC they didn't even directly - officially - govern the Greek cities of the Pentapolis on the eastern Libyan coast. The rulers of Cyrene and Barce were killed at this time and the satrap of Egypt, only recently conquered by Persia, demanded that the assassins be handed over. When he was refused, Barce was besieged, the assassins captured and executed, and a large portion of the city's population was shipped over to form a new city of Barce within the boundaries of Bakhtrish. It's no wonder that Bactria became so heavily influenced by Greek culture - even before Alexander's conquests.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from From Democrats to Kings: The Brutal Dawn of a New World from the Downfall of Athens to the Rise of Alexander the Great, Michael Scott, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Persica, Ctesias of Cnidus (original work lost but a section is repeated by Photius in ninth century AD Constantinople), and from External Link: Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

c.546 - 540 BC :

During his campaigns in the east, Cyrus the Great initially takes the northern route from Persis towards Bakhtrish and Suguda to reassure or subdue the provinces. This route probably involves the 'militaris via' by Rhagai to Parthawa. At some point Cyrus builds a line of seven forts to defend his frontier in Suguda against the tribal Massagetae to the north, the strongest of these being Kyra or Kyreskhata (Cyropolis - the Greek form of its name). Then he takes the more difficult southern route, destroying Capisa along the way (possibly Kapisa on the Koh Daman plain to the north of Kabul - which is possibly also the Kapishakanish named at Behistun as a fortress in Harahuwatish).

Cyrus the Great freed the Indo-Iranian Parsua people from Median domination to establish a nation that is recognisable to this day, and an empire that provided the basis for the vast territories that were later ruled by Alexander the Great On a fresh leg of the campaign, Cyrus enters the Dasht-i-Lut desert (the modern Dasht-e Loot) on the eastern route out of Karmana towards Harahuwatish. His army faces crippling loses but for the assistance provided by the Ariaspae on the River Helmand. They are named 'the Benefactors' (Greek 'Euergetai') by Cyrus in thanks. This route appears to have been poorly reconnoitred, hinting at a lack of Persian knowledge of this region (and therefore a lack of preceding Median occupation if the existence of its eastern empire is to be believed).

520s - 510s BC :

Dadarshish / Dādari / Dâdari : Satrap. Quelled rebellion in Mergu.

522/521 BC :

Upon the execution of the Persian usurper, Smerdis, the Cyaxarid, Fravarti, tries to restore Median independence. He is defeated by Persian generals and is executed. The same happens in Armina, Parthawa, and Verkâna whose inhabitants, as Darius the Great reports, had also joined Fravarti. The quashing of the insurrections from Armina to Parthawa is chronologically coordinated in Persian records and occurs between May and June 521 BC.

Another major rebellion takes place in Mergu (referred to as Margush in this instance) towards the end of 522 or 521 BC (scholars disagree over the year, although it is agreed that the rebellion is put down in December). Darius sends against him Dadarshish, satrap of Bakhtrish, and the rebellion is duly crushed.

516 - 515 BC :

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gandhar and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka. Along the way the Sakas are largely defeated and conquered, but probably only along the borders.

The River Oxus - also known over the course of many centuries as the Amu Darya - was used as a demarcation border throughout history and was also a hub of activity in prehistoric times - but during this period it flowed right through the heart of the region that was known as Bactria c.515 BC :

Both Arcesilaus of Cyrenaica and Alazeir, ruler of the sister city of Barce, are murdered in that city. Help is requested of Satrap Aryandes of Egypt who provides her with an army and strengthens his own hold over the Pentapolis. Barce is besieged and captured, the implicated murders of Arcesilaus are put to death, and a large proportion of the population is carried off into Persian slavery in a new settlement of Barce which is located in distant Bakhtrish.

Megabernes : Son of Spitamenes. Satrap of the Barcanians.

c.515 BC : The unreliable Ctesias has Cyrus the Great in 530 BC appointing Cambyses as his successor. He also makes two appointments to satrapies, placing Spitaces in command over the Dyrbaeans and his brother Megabernes over the Barcanians. Since the Barcanians are not moved to the region until around fifteen years later, this appoint has to be a later one, or to a different location. It may not be coincidental that the same Megabernes can be found as satrap of Verkâna in or around this time.

fl 500 BC :

Artabanos : Brother of Darius I. Satrap of Bakhtrish (& Suguda?).

fl 480 BC :

Masistes : Brother of Xerxes I. Satrap of Bakhtrish (& Suguda?).

? - 464 BC :

Hystaspes : Son of Xerxes I. Satrap of Bakhtrish (& Suguda?). Killed?

465 - 464 BC :

Artabanus the Hyrcanian kills Xerxes in collusion with the eunuch of the bedside and subsequently takes control of the empire, ostensibly as a regent for Xerxes' three sons. Artabanus has the murder pinned on the eldest of these, Darius, and has him killed by the youngest son, Artaxerxes. Artaxerxes accedes to the throne before Artabanus attempts to murder him too. In the end, it is Artabanus who dies, but Artaxerxes is forced to defeat the second of Xerxes' sons, Hystaspes, satrap of Bakhtrish and his own brother. This brief civil war is ended when Artaxerxes defeats the forces of Hystaspes in battle during a sandstorm.

360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

? - 329 BC :

Bessus / Artaxerxes V : Satrap of Bakhtrish & Suguda. Murdered Achaemenid Darius III.

330 - 328 BC :

In 330 BC Suguda becomes part of the Greek empire despite the efforts of Bessus, self-styled 'king of Asia', to retain at least some of the Persian territories. His claim is legal, since Bakhtrish is traditionally commanded by the next-in-line to the throne and he has already murdered the former holder, Darius, but Persia has already been lost and his loose collection of eastern allies - which includes the other two most senior officials, Barsaentes of Harahuwatish and Satibarzanes of Haraiva - provides nothing more than a sideshow to the main event - the fall of Achaemenid Persia. Still, it takes Alexander the Great two more years to fully conquer the region.

In his Hannibal Barca moment of brilliant tactical manoeuvre, Alexander the Great confounded expectations by entering Bakhtrish (Bactria) from the southern side of the Hindu Kush mountain range In Bakhtrish, Bessus returns to his capital to organise the resistance by the eastern satrapies. Alexander enters Bakhtrish in 329 BC via the Hindu Kush, which has been left undefended. After burning the crops, Bessus flees east, crossing the River Oxus. By now his own mounted levies are deserting en masse, and he is seized by several of his chieftains and handed over to the Macedonians. At Hamadan, the traditional Persian punishment for rebels and regicides is carried out on him, with his nose and earlobes being removed. After this he is executed, possibly by crucifixion, decapitation, or by being torn apart by two recoiling trees (sources differ). From here, Alexander proceeds into Suguda.

Argead Dynasty in Bactria :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Bactria was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 305 BC.

Bactria's appointed satraps during the Achaemenid period were usually royal princes or members of the highest social elite. Information about the satrapy's administration comes predominantly from the time of Alexander's campaign. The minor satrapy of Margiana was also under the oversight of the satrap of Bakhtrish, as apparently was much of the Central Asian region, as proven by the Behistun inscription. The southern border with the province of Gandhar was formed by the Hindu Kush, which today still marks the frontier of numerous Afghan provinces. To the north the River Oxus (Amu Darya) marked the frontier with Sogdiana, but the borders can only roughly be estimated where they met Aria to the south-west, Margiana to the west, and a region to the east which had, in the earliest phase of Achaemenid occupation, formed the minor satrapy of the Dyrbaeans.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Frank Lee Holt, from The Generalship of Alexander the Great, J F C Fuller, from the Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Warfare, J Woronoff & I Spence, from A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith (London, 1873), and from External Links: The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and Encyclopaedia Britannica.)

330 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

329 - 328 BC :

Persian resistance in the east to Alexander the Great's invasion is primarily centred in Bactria. Alexander enters the province in 329 BC via the Hindu Kush, which has been left undefended. After burning the crops its final Persian satrap, Bessus, flees east, crossing the River Oxus where he is seized by several of his chieftains and handed over to the Macedonians. Bactria has been taken and Sogdiana is next. Artabazus is created satrap of Bactria.

The route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns are shown in this map, with them leading him from Europe to Egypt, into Persia, and across the vastness of eastern Iran as far as the Pamir mountain range 329 - 328 BC :

Artabazus : Phrygian satrap of Bactria. Resigned his position.

328 BC :

Clitus / Cleitus the Black : Satrap. Killed by Alexander the Great in a drunken quarrel.

328 BC :

Following the resignation of Artabazus, Clitus is given the post of satrap of Bactria along with command of 16,000 Greeks who had formerly fought under the Persians as mercenaries. He sees this posting as a reduction of his influence and position with Alexander and, at a banquet in the satrap's palace at Maracanda (the capital of the satrapy of Sogdiana, modern Samarkand), the two get into a drunken quarrel. Enduring gross insults from Clitus, in his rage Alexander runs him through with a spear. Almost immediately he deeply regrets the death of his former friend (the scene is well depicted in the feature film, Alexander (2004), although the location is transferred to India).

328 - 321 BC :

Amyntas Nikolaos : Greek satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, & Sogdiana.

328 - 321 BC :

Scythaeus : Greek satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, & Sogdiana.

323 - 321 BC :

Philip / Philippus : Greek satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, & Sogdiana, then Parthia.

321 BC :

With Philip being reassigned to Parthia, his replacement in the east is Stasanor the Solian, former satrap of Aria and Drangiana. This new satrap is the brother to Stasander, his replacement in Aria and Drangiana. Perhaps he also has more of a focus towards the Northern Indus territories than the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, as later suggested by events. His territory initially extends as far north as Ferghana, which contains the city of Alexandria Eschate ('the Furthest', possibly modern Khojend but see the Ferghana introduction for more details), while Stasander also has ambitions.

The various territories that made up the satrapy of the Northern Indus (Punjab) which was centred over the mighty River Indus, alongside those of Gandhara, would go on to form the heartland of Indo-Greek control of the east in the remaining centuries BC 321 - 312 BC :

Stasanor the Solian : Greek satrap of Chorasmia to Sogdiana, & Nth Punjab (316 BC).

320s BC :

In the 320s BC, the Greeks under Alexander, like the Persians before them, place the Amyrgian Sakas beyond Sogdiana, across the River Tanais (otherwise known as the Iaxartes, Jaxartes, or Syr Darya, which forms the boundary between Sogdiana and Scythia). This is thanks to their having encountered them after crossing Sogdiana and the Syr Darya in the approximate region of Alexandria Eschate. It is generally accepted that they control all of Ferghana (immediately to the east of Sogdiana) and the Alai Valley. Indeed, they may have been relocated onto the plain following their conquest by the Persians.

316 - 312 BC :

The Wars of the Diadochi decide how Alexander the Great's empire is carved up between his generals, but the period is very confused, especially in the east. These provinces appear to be invaded and controlled by the Antigonids for a period, with General Antigonus being responsible for the death of Eudamus, satrap of the Northern Indus. However, at some point in 316 BC, Stasanor the Solian, satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, and Sogdiana (with Ferghana) seizes the Northern Indus while his brother seizes Parthia. Clearly the two are either working in unison with Seleucus of Babylonia from the beginning or are attempting to stamp their own independent authority on much of the east. Unfortunately, Stasander is removed from office in 315 BC.

315? - 305? BC :

Sophytes : Greek satrap of Bactria or vassal of Stanasor?

315 - 305 BC :

Proof of the growing independence of the Greek commanders in the east of the empire is provided by numismatic (coin) evidence. Several local issues of gold, silver, and bronze are struck in the names of independent satraps, including Sophytes and Vakshuvar (possibly Oxyartes of Paropamisus or his successor) between 315-305 BC. It is impossible on the basis of the available evidence to say whether this Sophytes has replaced Stanasor as satrap of Bactria or whether he governs a neighbouring region as Stanasor's equal or vassal. Perhaps most likely is the possibility that he becomes satrap, or assistant satrap, of Bactria when Stasanor focuses his attention on the Northern Punjab from 316 BC. The coinage of Sophytes is greatly attributed to a Bactrian mint on the basis of its distribution and evolution from earlier Greek coinage types, supporting that possibility.

The Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC ended the drawn-out and destructive Wars of the Diadochi which decided how Alexander's empire would be divided 312 - 306 BC :

Bactria is taken by the Seleucids around 312 BC, and it is possibly this event that serves to end the reign of Stasanor. Some areas seem to have been lost to regional warlords, such as parts of Drangiana, but by far the larger part remains under the control of the Greek satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana and, after 256 BC, the kings of Bactria.

Macedonian Bactria (Greco-Bactrian Kingdom) :

The unexpected death of Alexander in 323 BC changed the situation dramatically within his vast Greek empire. Immediately his generals divided the empire between them. Seleucus was able to expand his holdings with some ruthlessness, building up his stock of Alexander's far eastern regions as far as the borders of India and the River Indus (Sindh). Appian's work, The Syrian Wars, provides a detailed list of these regions, which included Arabia, Arachosia, Aria, Armenia, Bactria, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia (as it was known) by 301 BC, Carmania, Cilicia (eventually), Drangiana, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Media, Mesopotamia, Paropamisadae, Parthia, Persia, Sogdiana, and Tapouria (a small satrapy beyond Hyrcania), plus eastern areas of Phrygia.

Following the conclusion of the Wars of the Diadochi between the generals, Bactria (or Bactriana) was governed by Macedonian satraps. The descendants of these satraps became independent kings after Bactria had been cut off from the Seleucid heartland in Syria by Parthian incursion into central Persia. The kingdom consisted of the core provinces of Bactria and Sogdiana (to the north, reaching up to the southern shore of the Aral Sea, mostly within modern Turkmenistan). The latter of these two provinces also included Ferghana and the city of Alexandria Eschate. Located in one of the richest and most urbanised of regions, Macedonian Bactria quickly blossomed into a large, eastern Greek empire, but continual internal discord and usurpations saw it progressively fragmented and vulnerable to outside conquest. The easternmost section was soon almost permanently separated from Bactria and came to be known as the Indo-Greek kingdom. Ironically this outlived its mother state following an invasion of barbarians from the north.

The chronology of the Indo-Bactrian rulers is based largely on numismatic evidence (coinage). There are few written accounts, and other records are relatively sparse, while frequent internecine conflicts make the facts even harder to pin down, so dates are rarely reliable. Some possible kings are known only from a few coins, and the interpretation of these can sometimes be very uncertain. The Chinese explorer, Zhang Qian, recorded Bactria as Daxia to further complicate matters.

(Information by David Kelleher and Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau, Jeffrey D Lerner (1999), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Encyclopĉdia Britannica, and Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Silk Road Seattle (Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington), and Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, Marcus Junianus Justinus (Rev John Selby Watson, Trans, 1895), via Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum, and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org, and Turkic History. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991) has been followed.)

306 - 256 BC :

The Fourth War of the Diadochi soon breaks out. In 306 BC Antigonus proclaims himself king and governs territory known as the Empire of Antigonus, so the following year the other generals do the same in their domains. Polyperchon, otherwise quiet in his stronghold in the Peloponnese, dies in 303 BC and Cassander of Macedonia claims his territory. The war ends in the death of Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. Seleucus is now king of all Hellenic territory from Syria eastwards. For the next fifty years Bactria is governed by his Seleucid satraps as one of the easternmost sections of the empire.

The landscape around the walls of the ancient city of Bactra, capital of Bactria (shown here - now known as Balkh in northern Afghanistan, close to the border along the Amu Darya), was and still is very diverse, offering both challenges and rewards to any settlers there, including the newly arrived Greeks 305 BC :

Following the failure of Seleucus Nicator to reconquer Mauryan India, the regions of Paropamisadae (immediately east of Bactria proper, modern Kabul), Arachosia (modern southern Afghanistan and northern and central Pakistan, and perhaps extending as far as the Indus), northern Indus, and southern Indus are handed to the Mauryan empire in India by the Seleucids as part of an alliance agreement.

Demodamas : Seleucid satrap (governor-general) of Bactria & Sogdiana.

c.294 - 293 BC : A former general under Seleucid rulers Seleucus I Nicator and Antiochus I Soter, Demodamas later serves twice as satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana. During this time he undertakes military expeditions across the Syr Darya (otherwise known as the River Tanais) to explore the lands of the Sakas, repopulating Alexandria Eschate ('the furthest', modern Khojend) in Ferghana in the process following its earlier destruction by barbarians. His journeys of exploration take hum farther than any other Greek, barring perhaps Alexander himself, and his records of what he finds provide an important platform for later Roman writers.

c.293 - 281 BC :

? : One or more unknown Seleucid satraps.

c.281 - 280 BC :

Demodamas : Seleucid satrap for the second time.

c.280 - 256 BC :

? : Unknown Seleucid satrap(s).

256 - 248 BC :

Diodotus I Soter : Satrap. Declared the kingdom.

256 BC :

Diodotus declares independence from Seleucid Greek rule at the same time as the satrap of Parthia. It may even be the actions of Andragoras of Parthia which force the hand of Diodotus I Soter, since there is little immediate chance of Seleucid retaliation. However, although the written evidence is confused and somewhat contradictory, it is more likely to happen the other way around. Bactria declares independence and Parthia follows. Diodotus now rules the former provinces of Bactria, Sogdiana (to the north of Bactria), Ferghana (modern eastern Uzbekistan), and Arachosia (modern Kandahar). It is Strabo who confirms that Sogdiana at this time remains a Greco-Bactrian possession.

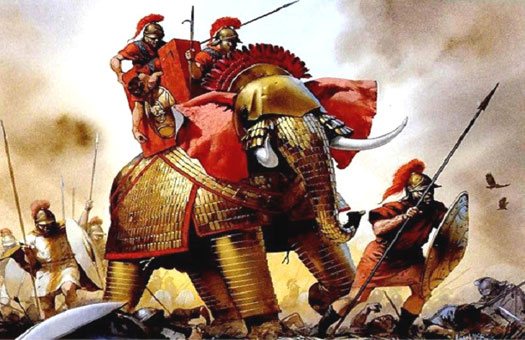

Seleucid war elephants were first introduced into the empire thanks to an exchange of gifts with the Mauryan emperor in India, these being the larger Indian elephants rather than the slightly smaller, now-extinct North African forest elephant used by Egyptians and Carthaginians Diodotus II : Son. Deposed by Euthydemus.

248 - 235 BC : Antiochus Nikator : Possible brother mentioned on coins but otherwise unknown.

c.235/230 BC :

Diodotus is overthrown by Euthydemus, possibly the satrap of Sogdiana. The date is uncertain and Strabo puts forward 223/221 BC as an alternative, placing it within a period of internal Seleucid discord.

235 - 200/195 BC :

Euthydemus I Theos : Former satrap in Sogdiana? Founder of the Euthydemids.

c.220 BC :

Euthydemus' realm is a large one, perhaps still including Sogdiana and Ferghana to the north, and Margiana and Aria to the west. There are indications that from Alexandria Eschate in Ferghana the Greco-Bactrians may lead expeditions as far as Kashgar (a little under three hundred and twenty kilometres due east of Ferghana), and Urumqi in Chinese Turkestan. There they would be able to establish the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC.

Even more remarkably, recent examinations of the terracotta army have established a startling new concept - the terracotta army may be the product of western art forms and technology. An entire terracotta army plus imperial court are manufactured using five workshops and a form of human representation in sculpture that has never before been seen in China. Archaeologists today continue the process of discovering new pits and even a fan of roads leading out from the emperor's burial mound, one of which, heading west, may be a sort of proto-Silk Road along which Greek craftsmen may be travelling.

208 - 206 BC :

Euthydemus repulses an effort at the re-conquest of Bactria by the Seleucid ruler, Antiochus III. Following defeat at the Battle of the Arius, Euthydemus successfully resists a two year siege in the fortified city of Bactra before Antiochus finally decides to recognise his rule in 206 BC. He offers one of his daughters in marriage to Euthydemus' son, Demetrius, but it may also be at this time that Euthydemus refers to great hordes of nomads accumulating on the northern borders, possibly meaning that Sogdiana has been removed from his control, and posing a threat to both their domains - Bactria and the Seleucid empire.

Antiochus subsequently marches across the Hindu Kush into the Kabul Valley and renews ties of friendship with an Indian king by the name of Sophagasenos. This king is otherwise completely unknown and cannot be matched with any more certain Indian rulers. Instead, given the location it seems that he may be a local ruler, perhaps in post-Mauryan Paropamisadae before it is seized by the Indo-Greek kingdom.

c.200 - 195 BC :

The last years of Euthydemus' reign probably sees he and his son cross the Hindu Kush and begin the conquest of what is now northern Afghanistan and the Indus valley. A great Indo-Greek empire rises far in the east.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi 200/195 - c.180 BC :

Demetrius I : Son. In Bactria & Indo-Greek territories.

185 BC :

The Mauryan empire falls apart. Demetrius annexes the western half of the empire, possibly as a show of support for the former allies, and possibly in part to protect Greek populations there. The territory gained includes Paropamisadae (northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan), all of Arachosia (southern Afghanistan), and modern Punjab and Kashmir, areas which could be included in the former satrapy of northern Indus. He advances as far as the Ganges and Pataliputra (modern Patna), although this advance is usually ascribed to the later king, Menander I.

c.180 BC :

Placing Demetrius' death (of unknown causes) on this date is generally accepted but far from certain. It is used in an attempt to fit in his death with the subsequent appearance of many successors in several regions of the enlargened kingdom. At some point, Demetrius invades the Sunga kingdom of Magadha from the west as Kharavela of Kaling is attacking from the south. Rather than press home his own attack, Kharavela turns on the Bactrian king and forces him to retreat. This event must be towards the very end of Demetrius' reign and at the beginning of Kharavela's for them to be ruling simultaneously.

Some of Demetrius' successors may be co-regents, but civil wars and territorial divisions are very likely. Pantaleon, Antimachus I, Agathocles, and possibly Euthydemus II are all theoretically linked as relatives to Demetrius. In Bactria, Euthydemus II rules, while in the Indo-Greek territories, Agathocles rules in Paropamisadae while Pantaleon rules in Arachosia.

190 - 185/180 BC :

Euthydemus II : Son. Either ruled afterwards or as a sub-king to him.

180? - 165? BC :

Antimachus I Theos : Son or brother. In Bactria & Indo-Greek territories.

170? BC :

Antimachus is apparently defeated by the able newcomer and former general, Eucratides (an alternative is that his territory is absorbed by Eucratides upon his death). Eucratides is opposed by Demetrius II from the Indo-Greek territories. who apparently returns to Bactria with 60,000 men to oust the usurper, but he is defeated and killed in the encounter. Antimachus I also fights against Eucratides, but ultimately is defeated around 160 BC and Eucratides seems to occupy territory as far as the Indus. The Euthydemids are pushed out of Bactria, retaining only the Indo-Greek territories.

The successor to Antimachus I of Bactria was Eucratides I, with this silver tetradrachm being minted in his image at some point during the twenty-six years or so of his reign 171 - c.145 BC :

Eucratides I / Eukratides I : Bactrian. In Paropamisadae, Arachosia, & W Indus.

167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes the former province of Aria (now northern Afghanistan) from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. It seems possible that Aria (and possibly a rebellious Drangiana too) had already been conquered once by the Arsacids, with the Greco-Bactrians recapturing it, probably during the reign of Euthydemus I Theos. During the reign of Eucratides the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

The last statement raises the question of who in Sogdiana is standing against Eucratides. There exist a few coins which are minted under the command of one Hyrcodes, an otherwise unknown individual. Despite much speculation about whether he is based in Bactria or in Sogdiana and whether he commands in the second or first century BC, it seems most likely that he is an Indo-Greek opponent of Eucratides. However, if true, and if placing him around this date is correct, then he is unlikely to survive the imminent Saka and Greater Yuezhi invasions of Sogdiana.

The other eastern provinces, all of which still appear to be in Seleucid hands, must also fall to the Parthians very quickly after this - including Carmania, Gedrosia, and Margiana - although firm evidence to show a specific date appears to be lacking. Another date which may be valid for these losses is 185 BC, when Seleucus IV loses eastern Iran to Parthian expansion, but the fact that the Parthians fail to expand out of their initial conquests until Mithradates accedes makes this period a more likely one.

c.165 BC :

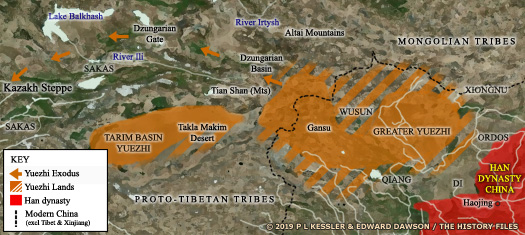

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement. However, Bactria seems to be at least a decade away from being affected by this, and the Greek kings continue to focus more on their battles against established rivals.

The Greater Yuezhi were defeated and forced out of the Gansu region by the Xiongnu, and their migratory route into Central Asia is pretty easy to deduct from the fact that they chose to try and settle in the Ili river valley below Lake Balkhash c.155 BC :

In the east, the Indo-Greek king, Menander, seems to repel the invasion by Eucratides, and pushes him back as far as Paropamisadae, thereby consolidating the rule of the Indo-Greek kings in northern India. After this, the Indo-Greek kingdom is permanently divided from Bactria.

c.150 - 145 BC :

Plato : Brother? In Bactria or Paropamisadae.

c.145 BC :

Under pressure in their established homeland thanks to the migration of the Greater Yuezhi, the Sakas enter the territory of Bactria around this time. They burn to the ground the city of Alexandria on the Oxus, an event which seemingly coincides with the death of Eucratides I himself. Generally presumed to be the modern ruins known as Ay Khanum (or Ai Khanum, literally 'Lady Moon' in Uzbek), the city is possibly also known as Eucratidia during its last days - almost certainly thanks to Eucratides I. The city goes into unrecoverable decline and today is entirely uninhabited.

c.145 - 140 BC :

Eucratides II : Son of Eucratides I?

c.140 BC :

Eucratides II is dethroned in a dynastic civil war which is sparked by the murder of Eucratides I. His successor, Heliocles I, is forced to face the reality of the kingdom's situation, with ever-increasing pressure by Sakas and Greater Yuezhi on its shrinking northern border. He moves the capital to the Kabul Valley, but it is only a temporary stop-gap.

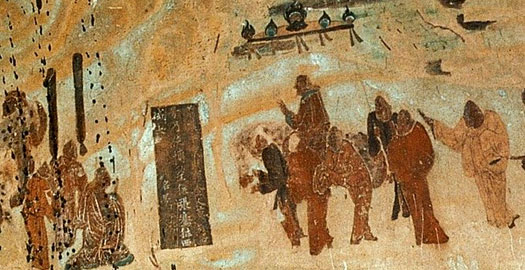

Zhang Qian was a Chinese ambassador and explorer who, between 138-126 BC, met and documented many of the steppe tribes, and referred to Bactria as Daxia c.140 - 130 BC :

Heliocles I : Probably killed during the Greater Yuezhi invasion.

c.140 - 130 BC :

Sakas have long been pressing against Bactria's borders. Now, following a long migration from the borders of the Chinese kingdoms, the Greater Yuezhi start to invade Bactria from Sogdiana to the north. Initially, Saka elements who are already in Bactria become vassals to the Greater Yuezhi.

Suvars (or Subars), a horse husbandry tribe known from the environs of Sumerian Mesopotamia (if in fact they are the same group - doubtful given the time span involved), now gain renewed prominence when they join the 'Tokhars' and Ases in the nomadic conquest of Sogdiana and Bactria about this time. The Ases have been equated with the Ases of the Pontic-Caspian steppe in the sixth century. They may be the same group, although this is debatable. A case can be made, however, by this nomadic group returning northwards to be swept up in early Turkic migrations towards the Caspian Sea - the Suvars seem to follow the very same course.

At around the time of the death of Indo-Greek King Menander in 130 BC, the Greater Yuezhi overrun Bactria and end Greek rule. Heliocles may possibly invade the western part of the Indo-Greek kingdom (part of the process of moving his capital to the Kabul Valley?), as there are strong suggestions that the Eucratids continue to rule there, especially in the form of Heliocles' presumed son, Lysias.

This photo depicts the single obverse side of a coin that was issued by the Indo-Greek King Menander, known in India as the great King Milinda In Bactria, Hellenic cities appear to survive for some time, as does the well-organised agricultural system. On the northern bank of the River Oxus the fortress religious centre of Takht-i Sangin (now in southern Tajikistan) survives and flourishes until the late Kushan period. The general region of Bactria comes to be called Tokharistan before one of the Greater Yuezhi tribes unites all of them under one banner to create the Kushan empire. Areas of Bactria later form parts of Afghanistan and most of eastern Turkmenistan.

Tokharistan / Tushara Kingdom (Bactria) :

Following the decline of Greek power in the region, Bactria became easy pickings for every successive nomadic invader who took a fancy to it. Takeovers by warrior elites of a subject population after any conquest are characteristic of steppe nomads of every flavour, and it is not surprising that the region witnessed various masters over the next seven centuries. The instability of dynasties here was very characteristic of nomads who came from open plains with no fixed borders, with their organisation consisting of mobile clans with their own leaders. Such a background demanded ruthless aggression, and alliances which were understood to be temporary in nature, this being the only way to survive.

When the Greater Yuezhi suffered yet another defeat at the hands of the Xiongu, this time with the latter allied to the previously subservient Wusun, they had no choice but to follow a migratory route away from their enemies. This route delivered them onto the Saka plains of the Ili river valley to the immediate south of Lake Balqash (the modern Lake Balkhash in Kazakhstan). From there they were forced to move again, entering Transoxiana from the direction of Da Yuan (the Chinese term for Ferghana). They penetrated Sogdiana from its northern reaches, initially dominating the Sakas who were already there.

Soon afterwards they followed the Sakas in invading the former Greek empire region of Bactria (Ta-hia or Ta-Hsia in Chinese records), by around 140 BC. This is where Chinese and western Classical records converge, allowing the Greater Yuezhi to be identified as Tocharians and for confusion to be created for modern scholars. At about the time of the death of the Indo-Greek King Menander around 130 BC they managed to terminate Greek rule in Bactria. Hellenic cities there appear to have survived for some time, as did the well-organised agricultural system, but the general area of Bactria soon came to be referred to as Tokharistan after its new masters. As a recognisable entity by that name, Tokharistan survived at least as far as the sixth century AD.

Tokharistan could also be equated with the Tushara kingdom of Indian literature which includes the Mahabharata. Tushara lies beyond north-western India itself, and is populated by mlechchas - barbarians - but more than enough time had passed since the great Indo-European migratory period that the Vedic Hindus would have no idea about the origins of these barbarians. Puranic texts equate them with the Sakas (Shakas), clearly seeing little difference between the dominating Greater Yuezhi and the dominated Sakas to the north of the Hindu Kush. In fact, such texts tend to find it hard to differentiate between any of the peoples to the north of the Hindu Kush. The Tibetan chronicle, Dpag-bsam-ljon-bzah (The Excellent Kalpa-Vrksa) references the Greater Yuezhi as the Tho-gar (seemingly another reference to Tokharians).

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan. Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies, Xinru Liu (Journal of World History 12, 2001), from The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, J P Mallory & Victor H Mair (2000), from Sogdiana, its Christians, and Byzantium, Aleksandr Naymark (Indiana University, 2001), and from External Links: Peering at the Tocharians through Language, and The United Sites of Indo-Europeans, and Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians, and Linguistics Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, and Indo-European Chronology - Countries and Peoples, and Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (J Pokorny), and the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Tocharian Online: Series Introduction, Todd B Krause & Jonathan Slocum (University of Texas at Austin), and Silk Road Seattle, Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington, and Afghan Gold, Treasures from the East (World Archaeology).)

126 BC :

The Chinese envoy, Chang-kien or Zhang Qian, visits the newly-established Greater Yuezhi capital of Kian-she in Ta-Hsia (otherwise shown as Daxia to the Chinese, and Bactria to western writers) and the rich and fertile country of the Bukhara region of Sogdiana. His mission is to obtain help for the Chinese emperor against the Xiongnu, but the Greater Yuezhi leader - the son of their leader who had been killed about 166 BC - refuses the request. Kian-she can reasonably be equated with Lan-shih or Lanshi, but the question of whether this is the Bactrian capital of Bactra (modern Balkh) seems to be much more controversial. It does seem to be likely though, despite scholarly objections.

However, although some modern scholars label the Bactra of this period as the Greater Yuezhi 'capital', Zhang Qian's own contemporary account makes it quite clear that the country is not ruled by a single king who is based in Bactra. Nor does the city contain a central administration. He carefully notes that: 'It [Bactria] has no great ruler but only a number of petty chiefs ruling the various cities'. The Chinese word used to describe the status of Lanshi can refer either to the capital (of a country) or, preferably here, a large town, city, or metropolis. The sense in which it is used clearly edges towards the latter sense.

Instead the Greater Yuezhi territory has been divided into five principalities, one for each of the main five Greater Yuezhi tribes (although there is the possibility that one or more may instead be formed of Sakas who had been there before the Greater Yuezhi and have now been absorbed into their ranks). These are the the Xiūmì (Hieu-mi), Guishuang (Kuei-shung or Kushan), Shuangmi (Shuang-mi), Xidun (Hi-tun), and Dūmì (Tumi). Although they are independently governed by their own allied prince or xihou, they act together as a confederation. It is also during this period that the Greater Yuezhi become literate, quickly progressing to become able administrators, traders, and scholars.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards Eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahanas of India 115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhar. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies. Although Carmania doesn't seem to be mentioned directly, its position between Drangiana and Persia would make it likely that this too is still in Parthian hands.

c.50? BC :

The Kushan tribe of Greater Yuezhi captures the territory of the Sakas in what will one day become Afghanistan, and have probably already caused the downfall of Indo-Greek King Hermaeus, conquering Paropamisadae in the process. The Kushans are becoming the dominant tribe of the Greater Yuezhi confederation, soon beginning the process of uniting the tribes under a single ruler in the process of creating the Kushan empire.

It is in the west of Bactria in this century that the 'Bactrian Gold' horde of Tillia Tepe is buried, in the graves of 'princely nomads'. At the heart of the horde is a glorious selection of objects from six richly-furnished graves (five women and one man) which are later excavated by an Afghan-Soviet team in 1978. A notable level of Greek influence can be felt in some of the finds, revealing the fact that Greek culture has had a lasting impact on the region, nearly three centuries after the death of Alexander the Great.

1st century AD :

A few coins have been found which are minted (probably) in the first century AD by one Phseigaharis. The coins all come from the prosperous Kashka-Darya valley of the western Pamir mountain range immediately south of Marakanda (Samarkand, with the valley now being in the region of Qashqadaryo in eastern Uzbekistan). Otherwise unknown except for these coin finds, Phseigaharis can be classed as a local ruler in Sogdiana, possibly a member of the Greater Yuezhi or one of their regional vassals.

Kushan

Empire / Guishang Kingdom :

The Kushan (or Kushans) founded an empire across southern areas of Central Asia and northern South Asia (reaching into north and west of India) at the very end of the first century BC. As a tribal people who were only just becoming infused with the prevailing local Indo-Greek culture and writing, their origins are somewhat murky and the foundation of their empire is just as indistinct. Contemporary records (mostly written by ethnic Greeks and Indians) show that they were a branch of the Indo-European Yueh Chi or Greater Yuezhi tribes following the mass exodus of that group from Chinese lands around 165 BC (see feature link for a broad overview of the Kushans).

According to J P Mallory, the native name for the historical Greater Yuezhi of Central Asia in the sixth to eighth centuries AD was possibly 'kuśiññe', meaning 'kuchean' in Tocharian B, 'of the kingdom of Kucha and Agni'. One of the Tocharian A texts refers to ārśi-käntwā, supposedly meaning 'in the tongue of Arsi'. The word 'ārśi' has been suggested as being cognate to 'argenteus', meaning 'shining, brilliant', but this is ridiculous. It is much more likely to refer to the verb 'to be', personified as 'truth'. Akni is simply the deity of fire, Agni. Kucha is suspected of being a tribal name which later became better known as 'kushan'. If 'arsi' is indeed 'to be' then this links the Kushans and Greater Yuezhi to the Germanic Indo-Europeans and their asura (Os, Aesir - see feature link, right, for more information) who were called Istvae. If nothing else, this would serve to further confirm the Greater Yuezhi as satem-speaking Indo-Iranians, something that is already fully evident in their regard. Examining more speculatively, could 'kuśiññe' have on the end of it the Celtic and Germanic plural suffix in yet another form, '-iññe'? In British (Belgic?) this was '-aun', in ancient German and common Celtic it was '-on', in modern German it is '-en', and in modern Welsh is it '-ion'. This would provide another link to other Indo-Europeans.

The Kushans may not have represented all Greater Yuezhi, but they certainly emerged as a powerful component of the confederation. The Greater Yuezhi entered Transoxiana and then started to invade Bactria by about 140 BC. At around the time of the death of Indo-Greek King Menander about 130 BC, they ended Greek rule in Bactria. Then they settled their conquered territory and the region became known as Tokharistan. There were five tribes which made up the Greater Yuezhi - although there is the possibility that one or more may instead have been formed of Sakas, a sister-group who had been there before the Greater Yuezhi arrival and who were now easily absorbed into their ranks. These five tribes are known in Chinese history as Xiūmì (Hieu-mi), Guishuang (Kuei-shung or Kushan), Shuangmi (Shuang-mi), Xidun (Hi-tun), and Dūmì (Tumi). Each of these seem to have settled their own territory around the start of the first century BC, although some uncertainty is including when assigning these, with the Xiūmì possibly taking Wakhan between the Pamirs and the Hindu Kush (on the eastern edge of what can be termed 'eastern Iran'), the Shuangmi taking Chitral, to the south of Wakhan and the Hindu Kush, the Guishuang creating a principality between Chitral and the Panjshir region, the Xidun taking Parwan on the Panjshir, and the Dūmì in Kabul.

A little over a century later, the Guishuang tribe - or Kushans as they are better known to western scholars - began to unite the other tribes together under one banner. The identification of Kujula Kadphises, the leader of this new confederation, with the Kieou-tsieu-kio, ruler of Kuei-shung, of Chinese records is pretty certain (also referred to as Kadphises I in English texts). Following the unification of the tribes, he secured the area from the rival Saka tribes, and then expanded his territory to include Gandhar (Indo-Greek Paropamisadae). Next he pushed on into central India, extending his borders as far as the Indus, with Indian sources referring to his kingdom as Kuśana. The empire's borders later reached China, whose scholars had raised what they knew as the Guishuang tribe to the Guishuang kingdom.

Dating for the Kushan empire is approximate, considerably uncertain (especially in its later years), and has been interpreted quite differently by some scholars. For example, some place its greatest ruler, Kanishka at AD 78-101 while others give him a starting date of AD 127, easily two generations later. The Chinese chronicle, Sanguozhi, can be used to date a late Kushan event to AD 229 while the Kushan king mentioned is shown by the prevailing chronology as having died in AD 207. If the Chinese dating is correct then the reign of this king, Vasudeva I, should clearly be put back by at least two decades.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Abhijit Rajadhyaksha and Edward Dawson, from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, from The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, J P Mallory & Victor H Mair (2008), from Osservazione sulla monetazione Indo-Partica. Sanabares I e Sanabares II incertezze ed ipotesie, F Chiesa (1982), from Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen, from Sogdiana, its Christians, and Byzantium, Aleksandr Naymark (Indiana University, 2001), from Life of Apollonius Tyana, Philostratus, from A New Bactrian Inscription of Kanishka the Great, J Cribb & N Sims-Williams (Silk Road Art and Archaeology 4: 75-142, 1995), from The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, J M Rosenfield (University of California Press, 1967), from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from The Fragmentary Classicising Historians of the Later Roman Empire, R C Blockley (Francis Cairns, Oxford, 1983), and from External Links: Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps), and Bactrian Chronology (SOAS, University of London).)

c.AD 1 - 30 :

Heraios / Heraus / Miaos : Kushan clan chief. Of (partial?) Indo-Greek descent?

c.AD 1 :

Heraios is the first recognisable Kushan ruler, gaining mastery within the Greater Yuezhi confederation and minting his own coins. His precise identity is open to some interpretation, with some scholars promoting the theory that he is a father or grandfather of Kujula Kadphises, the man who really unifies the confederation and leads it to conquest. Heraios is apparently confused by some scholars with one of the later Indo-Greek kings, Hermaeus Soter, and it is always possible that in the century and-a-half since their arrival in the region that the Kushan elite have already intermarried with the surviving Indo-Greek nobility and have adopted and adapted Indo-Greek names.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards Eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahanas of India 10 :

The Indo-Greek kingdom disappears under Saka pressure. It seems to be Rajuvula, the Saka kshatrapa of Mathura, who invades what is virtually the last free Indo-Greek territory in eastern Indus (Punjab), and kills the Greek ruler, Strato II, and his son. Pockets of Greek population probably remain for some centuries under the subsequent rule of the Kushans and Indo-Parthians. By now the Parthians already seem to have captured Kashmir from the Sakas, relieving them of an important prize.

Kujula Kadphises / Kadphises I : Descendant of Heraios or perhaps even the same person?

c.30 - 80 : Kujula Kadphises is the first Kushan chieftain to refer to himself as Kushan, and is therefore considered the first Kushan king. He may be a descendant of Heraios but he may instead be the same person. He also shares his name with some of the last Saka rulers, suggesting a possible family connection there.

During his reign, Kadphises subdues the Sakas and establishes his kingdom in Bactria-Tokharistan and the valley of the River Oxus (the Amu Darya), defeating the Indo-Parthians. Then he captures Paropamisadae, although its capital of Taxila may still remain in Indo-Parthian hands for a time. An Indo-Greek ruler by the name of Phraotes is noted as ruling there around AD 46.

This photo illustrates a Kadphises I coin which was discovered in the Bactria-Tokharistan region and which has on it a corrupt Greek legend c.30 - 50 :

At the founding of the Kushan empire, a long corridor of territory is seized by the Kushans between Bactria-Tokharistan and the middle course of the Amu Darya. This serves to create a Kushan barrier along the entire southern and western Sogdian border. The inference that can be drawn from the lack of Kushan empire coinage in Sogdiana (extremely rare), and the lack of any other apparent benefits of empire, is that Sogdiana is isolated deliberately or otherwise by this barrier, cut off from the Parthian empire and the west. A Kushan fortification wall which shuts the Iron Gates, a narrow path in the Baba-tag Mountains which is a popular connecting route, would suggest that the barrier is deliberate.

Vima / Wima Takto : Son. Aided his father on his campaigns.

c.80 - 90 :

Wima Takto, the son of Kujula Kadphises, is for a long time known only to scholars by the Greek legends on his coins - Soter Megas ('the Great Saviour'). However, the translation of an inscription by Kanishka I in Rabatak leads to the discovery that his name is in fact Wima Takto (the 'w' is pronounced in English as a 'v'). His other inscriptions and statues are known from further south and east in India, confirming his control of Gandhar and north-western India.

Wema Kadphises/ Kadphises II : Son (or nephew, and son of Sadakshana). No heir.

c.90 - 112 :

Kadphises II is another conquering Kushan, like his grandfather. He expands Kushan territory to the bordering provinces of China by following and controlling the Silk Road, and later ventures into India where he establishes holdings as far as Punjab and parts of modern Uttar Pradesh, being the first to introduce gold coinage there. By this time, the Kushans have also fully adopted the local Bactrian language, and its cursive Greek script, as the language and script of their empire. The empire itself, however, is large and fully multi-cultural and multilingual.

A staunch supporter of Buddhism without seemingly becoming one himself, Wema Kadphises apparently dies without an heir, and the kingdom is thrown into confusion as his kshatrapas (governors - the Indian form of 'satrap') fight amongst themselves. Kanishka, the kshatrapa of the kingdom's eastern province, wins the struggle and declares himself the successor.

Marco Polo's journey into China along the Silk Road made use of a network of east-west trade routes that had been developed since the time of Greek control of Bactria c.100 :

The Kushans capture former Indo-Greek Arachosia from the Indo-Parthians and expand their borders right up to the edge of the Parthian empire. With pretenders to the Parthian throne regularly basing themselves in eastern Parthia, King Pacorus is unable to do anything about it.

Kanishka I 'the Great' : Former governor and possible grandson of Kadphises I.

c.112 - 132 :

Kanishka expands the empire even further, gaining himself the epithet of 'the Great'. He annexes various regions of India; Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Kashmir, Malwa, Rajputana, and Saurashtra, and extends his rule as far as Khotan (southern India). He also campaigns northwards to capture Transoxiana (now Tajikistan and southern Uzbekistan) and apparently dominates the Tocharians of the Tarim Basin on the route towards China. He makes Purushpura his capital (modern Peshawar in Pakistan) and appoints kshatrapas to rule his vast territories including in the former territory of the Sakas (Saka officials remain in office in Mathura). He may also use Greek script on his earlier coins, inherited from influences in former Bactria which may still be evident in his day.

c.132 :

Despite being a successful king and general, Kanishka is apparently killed by his own soldiers during one of his military expeditions to China. The Saka Western Kshatraps in India take advantage of the empire's momentary weakness and begin to re-establish their independence.

The various territories that made up the Southern Indus (Sindh) had long been fought over as a form of gateway into India 'proper' c.132 - 136 :

Vashishka : Son? Little-known ruler with a very short reign.

c.136 - 168 :

Huvishka : Son or brother of Kanishka.

c.136 :

Having secured the throne, Huvishka continues to issue gold coins, greatly expanding the variety of coin designs and producing more gold coins than all other Kushan authorities combined. These are produced mainly in Bactra (Balkh), to the north of the Hindu Kush, and Purushapura (Peshawar) to the south in Gandhar, as well as in smaller centres in Kashmir and Mathura. The reign of Huvishka appears in general to be largely peaceful, spent on consolidating Kushan control over northern India and largely moving the centre of power to the southern capital of Mathura.

Vasudeva I / Bodiao : Last great ruler. 'King of the Da Yuezhi Intimate with Wei'.

c.168 - 207 :

A Chinese chronicle known as Sanguozhi records that Vasudeva sends tribute to the Chinese emperor, Cao Rui of Wei. Chinese records know Vasudeva better as as Bodiao, while they still refer to the Kushans as Da Yuezhi, their name for Greater Yuezhi who earlier lived along the borders of the Chinese kingdom. The date recorded for the arrival of the Kushan envoy in China is on Guimao of the twelfth month, in the third year of Taihe which has been equated to AD 229, clearly a little late for the chronology used here. This could be used as confirmation that the later dating for all Kushan rulers is more viable (see the introduction).

Cao Wei coinage is comparatively rare - unsurprisingly for a dynasty that replaced itself after less than half a century - and surviving issuances show a decline in quality during that period The vacuum created by the Chinese retreat in Central Asia is apparently filled by Vasudeva. He may also be the Indian king who transfers the relics of the apostle St Thomas from India to Mesopotamia. It is during this late second century period (or early in the third century) that the Kushan empire captures the province of Aria from the Parthians.

c.207 - 221 :

Kanishka II : Lost Bactria/Tokharistan to Sassanids.

c.221 - 231 :

Vashishka

223 :

The results of the SOAS's Bactrian chronology project are announced in 2008. The project has determined that the starting point of what is known in ancient documents as the 'Bactrian era', which has its own dating, is the foundation of the Sassanid dynasty in AD 223. In many cases, it is now possible to calculate the exact year of a Bactrian era document, even down to the exact day on which a document was written (simply add 223 to the Bactrian era date).

c.230 - 250 :

The end of Vasudeva's reign in AD 207 apparently coincides with the rise of the Sassanids and the commencement of their invasion of north-western India, although the dating for the main invasion fits with Vashiska and his successor around 230-250. Perhaps there is a first, preliminary invasion followed by a much greater second, or perhaps again the later Kushan dating fits better with external events.

The Kushans are toppled in former Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria (more recently better known as Tokharistan) and are forced to accept Sassanid suzerainty, being replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the Kushanshahs or Indo-Sassanids. There is a split in Kushan rule, so that a separate, eastern section rules independent of the Sassanids, while some of the nobility remain in the west as Sassanid vassals. Even so, Kushan power still gradually wanes in India. If the Western Kshatrapas have remained under Kushan domination to this point then they are almost certainly released from it now.

c.231 - 241 :

Kanishka III : Eastern king in Punjab. Stamped coins with 'kaisaro' (Caesar).

c.241 - 261 :

Vasudeva II : Eastern king in Punjab.

c.241 :

Very little is known of Vasudeva II, and his successors are even more uncertain, making it clear that Kushan authority and influence is fast diminishing even in the limited parts of India which they still govern. The very last Kushans who claim to rule seem to do so further to the west according to numismatic evidence, in Arachosia and Gandhar, where they probably fall under the overlordship of the Kushanshahs.

Two sides of a coin issued by Vasudeva II, a gold stater showing the king standing at the altar (on the left), while honouring the Central Asian (Indo-Iranian) goddess, Ardoksho who is seated facing outwards (on the right) c.245 :

Around this year, Shapur I devolves direct Sassanid rule in what is now Afghanistan by creating a buffer state which is governed by the Kushanshahs. They replace the Kushan nobility as the holders of power in the east. Kushanshah coins, initially issued mainly to the north of the Hindu Kush, are also soon to be found to the south in the Begram/Kapiśa area alongside issues by Kushan King Vasishka, suggesting a period of competition between the two sides in this region. With the next Kushanshah, Pēroz I, the Kushanshahs start to displace the later Kushans from Gandhar, confining them to Mathura in northern India, where they are reduced to local princes.

c.260 :

This could be the point at which Shapur seizes Sogdiana and makes it part of the Sassanid empire. Much of it is occupied for a time (Marakanda, for instance (modern Samarkand), while part is occupied for a longer period (Bukhara especially). It seems that the new masters of Iran have, at the same time as Kushan power is on the wane, broken through a Kushan barrier that has until now isolated Sogdiana. If the Kushans had indeed still been holding onto Bactria-Tokharistan, they have now certainly lost it.

Vasudeva III? : Son?

Vasudeva IV? : Son? Possibly governing in Gandhar.

c.261 - ? :

Vasudeva of Kabul : Son? Possibly ruling in Kabul.

c.300 :

The Guptas have established themselves in Bihar in northern India and rule a few small Hindu kingdoms within the territory of the ancient kingdom of Magadh. One Chandragupta succeeds his father as a local chief within Magadha (covering parts of the modern Bihar state). He increases his power and territory through marriage, gradually incorporating more and more of northern India under his control.

c.310 - 325 :

Chhu : Governor in Taxila region (Northern Indus) under the Guptas.

c.321 :

By now the Guptas have confirmed their control over the northern plains of India. Kushan rule is definitely ended, with what remains of their later core territory - around Purushapura (Peshawar) to the south in Gandhar, and Taxila - being governed by Kushan figures who may well represent the tail end of the former ruling nobility. However, they do maintain the Kushan coinage style in greatly reduced values.

The now-dominant Guptas of northern India issued a large number of gold coins, the two sides of this example being of a 'King & Queen on Couch / Vaikunth' type from the reign of Chandragupta I c.325 - 345 :

Shaka : Governor in Taxila region (Northern Indus) under the Guptas.

c.350 - 375 :

Kipunada / Kipunandha : Governor in Taxila region (Northern Indus) under the Guptas.

c.360s - 380s :

Scholarly interest in a new name in Central Asia at this time - the Kidarites - is greatly revived in the early twenty-first century by the discovery of a whole new series of Kidarite copper coins, from the Bhimadevi/Shiva shrine at Kashmir Smast in the mountains of northern Pakistan. The Kidarite leader, Kidara, who is active in the 390s is used to name this group of coins but he is only one of several Xionite rulers in Bactria and Gandhar during the fourth and fifth centuries (albeit the best-known of them).

Coinage issues in the names of Kirada, Hanaka, Yosada, and Peroz all appear on coins which are issued before those in the name of Kidara, highlighting several previously unknown Kidarite leaders (Peroz aside). Only approximate dates can be assigned to them, however, as coins usually lack the more precise dating of the written record.

c.375 :

There is no evidence of any Kushans after Kipunada. Having been subjugated by the Gupta kings, the rump eastern Kushan state is soon conquered by the invading Kidarites. They, in turn, claim to be the rightful successors of the Kushans and Kushanshahs. Any possible survivors in the west are probably displaced by the Hephthalites. This is the next wave of barbarians to invade the territory of the Kushanshahs, where they conquer former Bactria and Gandhar to form their own kingdom.

Xionite Bactria / Tokharistan :

Starting in the fourth century AD, a general invasion of nomadic tribes began to overwhelm southern Central Asia and northern South Asia (a region which can be combined under the label of 'eastern Iran'). This wave of barbarian invasions is attributed to tribal confederations which originated on the Central Asian steppe. The route southwards from there was not a new one though. It had been followed two millennia before by the ancestors of the Indo-Iranians, and also in part by the Tocharians who gave their name to Tokharistan.