| CELTIC TRIBES 13th Century BC - 6th Century AD :

The story of the Celts is one that links back to the earliest appearance of Indo-Europeans in Europe. In very basic terms, Europe of the late third millennium BC provided a home for a group of recently-arrived Indo-European people who all spoke the same language. This was a centum branch (a West Indo-European-speaking branch) which later divided into the Italic, Celtic, Venetic (of the Adriatic), and probably Liburnian and Illyrian language groups. A date for the split is conjectural, but 3100-2600 BC seems likely (see the Indo-European page for a more detailed discussion).

As time passed these groups began to drift apart, each group speaking the tongue a little differently. Along what was probably the southern and western edge of these tribes, each group began to expand further south and west. One group settled in what is now north-eastern Italy in the region of Venice (the Adriatic Veneti). Another group headed south into the Italian peninsula (the Villanova culture and others). The last group headed west into what is now France, Spain and Portugal.

Linguistically, one characteristic of the last group is their retention of a 'kw' sound from the original Indo-European language. Some of these people migrated into the British Isles and spread even farther west to Ireland where their version of the language survives to this day. But in the old homeland, things were changing. Instead of a short stabbing bronze sword, a long slashing bronze sword became dominant. Instead of the 'kw' sound at the beginning of many words, they were replacing this with 'p' sound. Population pressures forced these people in the old homeland to migrate outwards; and they did so in all directions: north to the Early Baltics coastline (the Belgae, among others), east into Eastern Europe, south towards Italy, and west into France (Gaul). They became the dominant society in Europe.

Meanwhile, a group of the first wave Indo-Europeans in the Latium region of the Italian peninsula, under the influence of pre-Indo-European civilisation (the Etruscans), began the very organised military conquest of their neighbours. Some of these were non-Indo-Europeans, but most were their not-too-distant relatives the Italic and Celtic tribes. Once conquered, they easily adapted their speech to the closely-related Latin. In Iberia the 'kw' sound (such as 'qu') was the same, making the transition easy after conquest - and so even today Spanish and Portuguese are very similar to Italian and their mutual mother, Latin - all of them being based on the Q-Celtic of the First Wave. In France (Gaul) the old tongue had altered more, and so the Gaulish version of Latin was rather strange sounding (this was the P-Celtic of Celts of the Second Wave). Naturally not all linguists accept this version of events, but it is popular and also makes very good sense.

The difference between Q-Celtic speakers and P-Celtic speakers was mirrored in later progression, with the Latins regarding the P-Celtic-speaking Gauls to be an enemy that was to be ridiculed (as well as feared). In general terms, the Romans coined the name 'Gaul' to describe the Celtic tribes of what is now central, northern and eastern France, but the root of this name, and the possible origins of the Celtic/Keltoi name as a whole are explored in more depth in the accompanying feature. In very basic terms it seems to mean 'to prevail, be strong', as seen in languages ranging from Old Norse and Old High German to Latin and Latvian.

Most individual Celtic and Germanic tribal names were made up of a core word, plus two suffixes, one indigenous and one Latin. For example, the Pictones name is not Picton, it is Pict. The Redones are Red (Reds in plural form in modern English). This is often overlooked when analysing tribal names. These names are examined in much greater detail in the entries for each individual tribe. In addition, the definite article was used as a suffix to denote a people, and since that time in which it was indeed used to denote a people, it appears to have evolved into a plural suffix in some subsequent languages. This affects the use of the '-on' plural suffix in many tribal name translations, but perhaps not seriously.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from The La Tene Celtic Belgae Tribes in England: Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R-U152 - Hypothesis C, David K Faux, from A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry, David K Faux, from The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W Anthony, and from External Links: The Works of Julius Caesar: Gallic Wars, and Tracing the dynamic life story of a Bronze Age Female (National Museum of Denmark, via Nature.com). Other major sources listed in the 'Barbarian Europe' section of the Sources page.)

from c.3300 BC :

Up until around 2800 BC, groups of Indo-Europeans first begin migrate into Greece, blending in with the indigenous populations to later form Mycenaean, Minoan, Cypriot and Italian culture. They also begin to arrive in north-western Europe, settling amongst earlier populations of Neolithic farmers and Palaeolithic hunters.

The Indo-Europeans had a strong horse culture, with the animals proving to be highly valuable status objects that also carried them on their long migration from the steppes into Europe and the Near East Anthony adds that the split between the Italic and closely allied Celtic language groups appears to occur between 3100 and 2600 BC. Then Bell Beaker decorated cup styles, domestic pot types, and grave and dagger types from the middle Danube are adopted around 2600 BC in Moravia and southern Germany, possibly as a result of trade rather than immediate migration. However, this material network could be the bridge through which pre-Celtic dialects spread into Germany. Austria, and Bavaria seemingly becoming the location in which proto-Celtic originally develops - in other words the language's homeland.

According to Ellis (1998), The large number of Celtic place-names still surviving in Switzerland and south-western Germany are therefore an indication that when the Celtic peoples appear in the historical record they are already well-settled in this area. He also echoes Hubert's views that the survival to this day of so many Celtic names for important geographical features (such as the rivers Rhine and Danube) in what are now German-speaking regions points to the names being of indigenous form and of long usage.

from c.2500 BC :

Central Europe's Bronze Age (2500-900 BC), which peaks around 1700 BC, marks the approximate beginning of the Unetice culture (which emerges out of the Bell Beaker culture). This is found on both sides of the Elbe and northwards to the Baltic Sea in what is today Czech Republic, western Poland and Germany. It represents a fusion of the Corded Ware and Beaker traditions and is considered by many to be proto-Celtic.

It is this Unetice group that introduces bronze objects into the region and makes prestigious objects mainly for the elite of the area, and mainly as status symbols. Many of these bronze objects ended up as votive offerings in bogs. It is not clear whether these people are ancestors of the eastern Hallstatt and La Tène Celts, but they may be cousins, and may also lay the grounds for a later possible presence of Belgae in this region.

One of the better-documented sites of this period is Auvernier on Lake Neuchatel in Switzerland. Radiocarbon and dendochronological dates suggest two occupations, in 2350 and 1950 BC (Suess and Strahm, 1970). There are remarkable similarities between sites in France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, and Italy (particularly around Lake Garda) at this time that shows extensive contact between the trans-Alpine and southern Alpine areas.

Auvernier on Neuchatel in Switzerland was one of the key development sites for the proto-Celts, with the area of the modern country providing the western section of the early Celtic heartland from c.2000 BC :

Following their gradual arrival over the previous few centuries, the Late Neolithic Celto-Ligurian tribes are in control of large areas of central and Western Europe. Represented by Bell Beaker culture, and with some knowledge of copper-working, they begin moving into the British Isles. Other Indo-Europeans arrive in territory between the Balkans and Persia, where the proto-Thracians and proto- Iranians form two large groups. The Balts occupy most of what is now northern Poland and large areas of western Russia. Illyrian tribes occupy an area of Southern Europe between the Italian peninsula (home of possibly close relatives to the proto-Celts in the form of the Italics) and modern Greece. Indo-Europeans have already moved from the Danube region into the Italian peninsula, and warlike Greek tribes (the early Mycenaeans) into the Mediterranean area.

The proto-Teutons enter and dominate most of the Scandinavian peninsula, where a racially distinct Germanic Nordic develops from a mixture of invading Indo-European Nordics and Old Stone-Age survivors. Indo-European tribes soon possess most of Europe at the expense of the earlier stock who are now either pushed into the more inaccessible parts of the Continent (such as the Aquitani around the Pyrenees), or become the lower strata of society, the untouchables of Europe.

As an aside, during the last few centuries prior to the Yamnaya horizon (which had seen the proto-Indo-European ancestors of the now proto-Germanics begin their migrations alongside the ancestors of the proto-Celts), cannabis may have been travelling from the Pontic-Caspian steppes to Mesopotamia and the early city states of Sumer. Greek kdnnabis and proto-Germanic *baniptx seem to be related to the Sumerian kuriibu. Sumerian dies out as a widely spoken language after around 2000 BC, so the connection must be a very ancient one. The international trade of the Late Uruk period (circa 3300-3100 BC) provides a suitable context for this trade.

The link between the early, proto-Indo-European form of the word cannabis (and therefore its probable Sumerian origin of kuriibu) to the proto-Germanic form requires a few steps. In the late Bronze Age, proto-Germanic groups are pretty isolated in southern Scandinavia and along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, but are theorised to be in contact with the proto-Celts (and possibly even dominated by them). In support of this is the realisation that 'cannabis' would need to pass through Celtic to reach its Germanic form: the initial 'k' would be a 'kw' in Q-Celtic (of the First Wave), transformed to a 'p' in P-Celtic (of the Second Wave), and then transformed into a 'b' in Belgic (northern Celtic), and finally adopted into Germanic. This appears to fit in with the idea that Belgic Celts dominate Northern Europe prior to the rise of the Germanic tribes around the fifth century BC.

c.1500 BC :

A new analysis in 2016 of the iconic Bronze Age woman known as Egtved Girl, whose well-preserved remains are unearthed near Egtved in modern Denmark in 1921, suggests she is born elsewhere and travels widely during her lifetime. By comparing strontium traces from the Egtved Girl to place-specific strontium signatures across north-western Europe, it has been possible to determine where she lives at different points in her life. Strontium signatures in her teeth, which are deposited in childhood, show that she is likely to be born in what is now south-western Germany, some eight hundred and four kilometres away (five hundred miles). The precise location is difficult to pinpoint but it places here right in the heart of the proto-Celtic Urnfield culture which may just beginning to show signs of emergence at this time.

Egtved Girl wears a well-preserved woollen outfit and a bronze belt plate which symbolises the sun - a well-travelled woman at the dawn of the Celtic Urnfield culture who found herself visiting Denmark Her hair and a thumbnail contain strontium, which is accumulated during the last two years of her life, by which time she is aged around eighteen. The strontium describes two journeys between Denmark and her birthplace. One theory for this is that she may be married off to help secure an alliance and perhaps the trade it will foster. This seems unlikely as it would involve only one journey from her birthplace to Denmark. More likely she is part of a trade mission, heading north on multiple trips during her lifetime, probably accompanying her parents. Given the likely domination of early Germanics by northern Celts, the party may even be collecting tribute.

Urnfield

Culture (Proto-Celts) (Late Bronze Age) :

The Urnfield culture (Ha A and B) is the label given to the earliest recognisably proto-Celtic group in Europe. The culture arose gradually in Central Europe, to the north of the Alps, between Bohemia and the Rhine, forming from earlier-arriving and earlier-forming Celto-Ligurian groups. This rise included the Upper Danube regions of Austria and Bavaria, and it rapidly spread to the Swiss lakes, the Upper and Middle Rhine valleys and, ultimately, further north and west. It gained its name from the cremation remains that were found in large urns.

The people of this culture had a well-developed Late Bronze Age warrior strata to their society, something that would also feature strongly in later Celtic society. The more important characteristics of this were prevalent across the full extent of the culture's spread throughout Europe, although it is likely that they followed the standard pattern of dividing into clans (tribes) that periodically sub-divided or absorbed other clans. Sadly they had no contact with any literate peoples who could record their existence in any detail, so nothing is known of them other than through archaeological evidence, perhaps supported by linguistic and cultural evidence that passed down through their successors.

In his work, The Celts, Powell stated that it was this total population of the so-called 'North Alpine Urnfield province', which was centred in southern Germany and Switzerland, that demanded special scrutiny in relation to the coming into existence of the Celts. He also noted that the pattern in rural settlement and economy, in material culture, and partly in burial ritual, that was established in the North Alpine Urnfield province is found to be continuous, however variously enriched it may later have been, into and throughout the span of the historical Celts. In other words, the Urnfield was recognisably Celtic in many of its key points.

Paul Reinecke classified this period as Hallstatt A and B, with the subsequent Iron Age periods being classed as Ha C and D. This corresponds to the Montelius III-IV phases of the Northern Bronze Age. The origin of the cremation tradition appears to be the Balkans, and it was this cultural grouping that replaced the indigenous Tumulus culture at a time of collapse and migration (which included the Israelite exodus from Egypt around 1230 BC and the collapse the Hittite empire in Anatolia around 1200 BC). Just who this Balkan group may have been is unknown, but it may have pre-dated another such (contentious) migration along the same route (almost certainly via the Danube) in the eighth century BC, which is known as the Thraco-Cimmerian Hypothesis.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide, Roger Collins, and Los pueblos de la España antigua, Juan Santos Yanguas, from Culinaria Spain, Marion Trutter (Ed), from Cultural Atlas of Spain and Portugal, Mary Vincent & RA Stradling, from A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry, David K Faux, and from The Celts, TGE Powell.)

c.1250 - 900 BC :

Social collapse and a dark age engulfs the Near East, largely due to climate-induced drought and crop shortages. During this period, Celto-Italic Indo-European groups in Europe filter into Italy, where they form the two main groups of Italic peoples, the Oscan-Umbrians (which includes the Opici and Umbri) and Latino-Faliscans (which includes the Latins).

One of the earliest proto-Celtic cultures has already started to appear in Central Europe, this being the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture, which replaces the preceding, indigenous Tumulus culture. Q-Celtic-speaking proto-Celtic groups also migrate outwards, some apparently ending up in Britain. The rapid expansion of Urnfield means that it almost literally engulfs Central Europe and even impacts upon the Baltic culture, very quickly taking over the entire south-western corner of Baltic dominance - central, eastern, and southern Poland - via the associated Lusatian culture.

Bird vases of the Urnfield were objects that were closely related to the belief system, and it may not be accidental that this vase was found next to a pot containing bird eggs in the cemetery of Békásmegyer, as the two objects together may emphasise the pots' symbolism of life and fertility c.1100 BC :

There is evidence, supported by archaeology, of the aforementioned early influx of Celts into Britain, where they eventually push back or integrate with the indigenous population and settle in the fertile south and east. They also later infiltrate into Ireland. This would explain later tradition which claims the conquest of the island of Britain by Brutus. This influx, however, would be little more than a new elite ruling the native Bronze Age population of the islands. Other Urnfield groups migrate into Gaul, such as the Vocontii.

The appearance of the proto-Villanovan culture in northern and central Italy bears some links to the later Celtic Hallstatt culture. At the same time, and for the next two or three centuries, a generalised group called Italics migrates into the Italian peninsula from the north. They have uncertain origins, but are largely accepted as being Indo-Europeans (cousins of the proto-Celts).

c.1000 BC :

Latins and other Indo-European Italic tribes continue to migrate into Italy. West Italics first, and East Italics later, the latter largely displacing the first group. Celtic tribes arrive in Iberia, probably in two waves, the first traditionally placed around 900 BC. More recently, however, there has been a tendency to identify the early arrivals as Indo-European or proto-Celtic tribes and argue for a process of infiltration over an extended period, from around 1000 to 300 BC, rather than invasions.

The first arrivals appear to establish themselves in Catalonia, having probably entered via the eastern passages of the Pyrenees. Later groups (more identifiably Celtic) venture west through the Pyrenees to occupy the northern coast of the peninsula, and south beyond the Ebro and Duero basins as far as the Tagus valley. It could be the strong Iberian presence that prevents the Celts from continuing down the Mediterranean coast.

This map showing Late Bronze Age cultures in Europe displays the widespread expansion of the Urnfield culture and many of its splinter groups, although not the smaller groups who reached Britain, Iberia, and perhaps Scandinavia too As can be seen from the map above, by this stage the Urnfield culture has formed several sub-groups or cultures in an unbroken line between the modern Netherlands to the heel of Italy, from eastern central Poland to the eastern Pyrenees, and from eastern France to western Ukraine.

These include: the Lower Rhine groups, the North Alpine groups, the Golasecca culture (in north-western Italy), the proto-Villanova culture (in central and northern Italy), the Middle Danube groups, the Knoviz culture (in southern Poland, Bohemia, and Moravia), the Lausitz culture (in eastern Poland), and the Gava culture (in the upper Balkans). Britain and the Atlantic coast of Western Europe are still dominated by the Atlantic Bronze Age system, while northern Poland and Germany and southern Norway and Sweden are dominated by the Nordic Bronze Age societies.

First

Wave Celts - Q-Celtic Speakers / Hallstatt Culture :

The first wave of Indo-European-speaking peoples to arrive in Western Europe were from the Italo-Celtic branch of Indo-Europeans. They displaced, and more often incorporated, the previous inhabitants, who appear physically to have been Mediterranean prehistoric folk who spoke non-Indo-European languages from the Dene-Caucasian language group. Historically, records exist of these indigenous peoples where they were mentioned by Greek and Roman sources. The ancient Greeks called the indigenous people in their area Pelasgians. The Romans knew theirs as Etruscans, and indeed received much of their early civilising influences from them. The Romans also encountered them as Aquitani, whom we know today as the Basques. In the British Isles there is speculation that some of the Picts may have been from this group of prehistoric folk.

Physically these early peoples appear to have been of middle height, slender, and with black hair and dark brown eyes. These characteristics are widely seen across Europe (in France, Italy, Portugal, Wales, etc), and indicate the ancestry of these peoples. There appears to have been another people, possibly predating the Mediterraneans, which older anthropologists called Alpines. Their range is mixed among the Mediterraneans, but in many places they were found along the western 'fringe' of Europe or, as in the case of the Alpines proper, in mountains. In Britain and Ireland this type is found scattered through much of the latter, and appears often in the former, especially in mid-Wales. This type is usually of a stocky build, and with a rounded head shape; colouration varies, which would be in line with an older stock much admixed with two major waves of invaders (Mediterraneans and Indo-Europeans) and long adapted to their environs.

Into this mix was added the proto-Celtic Urnfield culture which had greatly expanded Indo-European influence across many regions of Europe that previously had been populated entirely by indigenous groups. In the very heartland of Urnfield culture, between Switzerland and Bavaria, a new culture emerged around 800 BC called the Hallstatt. This was the first true Celtic culture, and its export outwards into western, southern, and Eastern Europe became the 'first wave' of Celtic expansion. More controversially, there may also have been expansion into Northern Europe. If the Urnfield culture had not already generated mixed Celto-Germanic groups itself, then this expansion can be claimed to have done so in its place, with this probable mixture rightly being claimed as the origin of the Belgic group of Celts.

The opinion has been expressed by some authors that in the eighth century BC a 'Thraco-Cimmerian' migration triggered cultural changes that contributed to the transformation of the Urnfield culture into the Hallstatt C culture, and thereby ushered in the European Iron Age. This theory is still highly controversial though. David Rankin was one author to expound it, stating that Celtic peoples owed their origin to a specifically eastern warrior culture imposing itself upon an Eastern European culture of the Urnfield, Lusatian type, and introducing the lordly habit of tumulus burial. The warrior culture of the Celts was actually the standard Indo-European warrior culture, but perhaps regional elements existed which were added to the Urnfield culture at just the right time.

As mentioned in the main introduction, above, the formerly single Indo-European language and culture quickly broke down into many regional variations, two being Iberian Q-Celtic, and Italian Q-Italic. These were quite similar, both cultures preferring the short stabbing sword, and speaking closely related languages. The first wave of Celts themselves were also Q-Celtic speakers, seemingly being most closely related to the Italic tribes such as the Latins.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from The La Tene Celtic Belgae Tribes in England: Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R-U152 - Hypothesis C, David K Faux, from A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry, David K Faux, from Celts and the Classical World, David Rankin, from The Civilisation of the East, Fritz Hommel (Translated by J H Loewe, Elibron Classic Series, 2005), from Europe Before History, Kristian Kristiansen, and from External Links: The Works of Julius Caesar: Gallic Wars, and Chiemgau Impact, and the Archaeology News Network, and Geography, Strabo (H C Hamilton & W Falconer, London, 1903, Perseus Online Edition). Other major sources listed in the 'Barbarian Europe' section of the Sources page.)

c.750 BC :

Celts start to expand from their traditional territory in southern Germany, expanding the early Hallstatt culture in Iron Age Europe. This culture is a direct progression of the previous Urnfield culture. Tribes such as the Lemovices and Mediomatrici begin to arrive in what becomes known as Gaul, although the migration and settlement period is an ongoing one that lasts as long as the culture itself. The earliest signs of Hallstatt culture come from the eastern Alps, in elite burials of the Hallstatt C people. The tribes here have become wealthy on the salt trade, amongst other commodities, and these Hallstatt C people are dominant until around 600 BC.

The Welsh hill fort of Caerau (pronounced Caer-eye) now stands on the edge of a modern housing estate on Cardiff's outskirts and with a road cutting through part of the lower hill This is also the period in which the Iron Age begins to arrive in Britain, introduced alongside early Celtic settlers. The site of Caerau in the later territory of the Silures shows evidence of this, although the initial spread of the Celtic newcomers is probably confined to the south and south-east coast before it moves inland. It is quite possible that with most of southern Britain held by Celts, the pre-Indo-European natives of the west and north respond to the threat by building defences that contain the latest technological advances, which are typical of those seen at Caerau.

The use of iron weapons would more quickly supplant the bronze ones as a matter of necessity, and pockets of pre-Indo-Europeans would survive and persist much as later Romano-Britons do in the face of Anglo-Saxon advances, with the natives adopting elements of the newcomers' weapons and fighting techniques as a matter of survival. Either way, Celtic language and tough iron swords gradually replace native language and soft bronze swords across the country over the course of the next 250 years.

c.730s - 720s BC :

It seems to be around this time that the window for the 'Thraco-Cimmerian Hypothesis' first opens. The Cimmerians and Scythians have suddenly positioned themselves as a more powerful collection of tribes which are not afraid of thundering around the Black Sea coast (on either side of the sea itself) and waging war against established kingdoms. It is known that Cimmerians later settle amongst the Thracian tribes, so to be that welcome they must share some common points of interest, such as language or culture. The common points would seem to be old Urnfield traditions in metalwork mixed with new Cimmerian influences from the Caucuses. Could they already be mixing with Thracians now, with some groups beginning to explore further along the River Danube to enter regions that are controlled by the Celts of the Hallstatt C culture? The weight of evidence shows that there is indeed a warrior culture of the horse/wagon complex in the eighth century BC and also a shift in production centres from Hungary to Italy and the Alpine region. This would match well with a Thraco-Cimmerian migration along the Danube (whether in person or by osmosis through neighbouring migratory groups).

In successive waves from the ninth to the sixth centuries BC these migrating warrior groups push west towards the headwaters of the Danube before veering off to the north. Ultimately, one branch follows the course of the River Elbe and a second backtracks west from the headwaters of the Rhine, heading north-east to the Elbe and then north into Jutland (where it theoretically forms, or merges with the ancestors of, the Cimbri).

c.700 BC :

The second 'wave' of Celtic migration into Iberia begins around this period (confusingly named, as it consists of first wave Celts). This is remarkably close in time to the Celtic migrations into Italy, around a century later. Overpopulation in southern Germany must be pretty bad at this time. Some elements of the Celtic populations in Iberia later migrate to Ireland, where in part at least they form a population known to the natives as the Erainn.

Not so much a sudden influx of Celts, the migration into Iberia is more a general progression of Hallstatt culture tribes arriving at the Pyrenees and forcing their way across. These Hallstatt Celts remain undisturbed by the later La Tène culture Celts until Iberia is conquered by Rome. It is this wave of Celts that ventures west through the Pyrenees to occupy the northern coast of the peninsula, and south beyond the Ebro and Duero basins as far as the Tagus valley. It is probably the strong presence of Iberians that prevents them from expanding further.

The Germanic peoples, still apparently occupying a possible original homeland in southern Sweden and the Jutland peninsula, appear to go through a period in which they are conquered by the Western Celts (Gauls) and remain subject to them (especially in Jutland). This leads to a good deal of cultural cross-contamination, with Germans exhibiting Celtic influences (in the form of words and names), and Celts exhibiting similar Germanic influences. This cross-cultural exchange is especially noticeable in many Belgic tribes of the first century BC, raising the possibility that they are the ones dominating the Germans at this time, not the Gauls.

The Lower Rhine shown here was a mighty, if crossable, barrier but the Cadurci crossed much farther upriver, in the middle of the seventh century BC c.650 BC :

The Cadurci are thought to migrate across the Rhine, leaving the Celtic heartland in southern Germany to enter the land that becomes known as Gaul. The Lexovii make the same journey. Other Celtic groups are also settling in the British Isles and Ireland around this time. Whether the Cadurci tribe itself exists at this stage is entirely unknown. More probably, the migrants are one or more larger tribes that later divide and settle Gaul. It could take a further two or three centuries for the Cadurci to find a permanent home near the Garonne and evolve the identity that is later recorded by Caesar.

Farther east, on the Black Sea coast, the name Tugdamme, a leader of Cimmerians at this time, strikes Edward Dawson as being Celtic, with an automatic reconfiguration to the Celtic 'Togodumnos' being an easy leap. Given the possibility that it may be Thraco-Cimmerians who influence the Celtic progression from Hallstatt to La Tène culture during the proposed migration west from the Black Sea, Tugdamme could be a name type that is adopted by the Celts from the Cimmerian warrior elite and is afterwards rendered as Togodumnos (or variants).

618 BC :

A huge early Celtic calendar construction is discovered in 2011 at the royal tomb of Magdalenenberg, near Villingen-Schwenningen in modern Germany's Black Forest. The order of the burials around the central royal tomb fits exactly with the constellations of the northern hemisphere. Whereas Stonehenge in Britain is orientated towards the sun, the burial mound at Magdalenenberg, which is over a hundred metres wide, is focused towards the moon.

The builders position long rows of wooden posts in the mound to be able to focus on the lunar standstills, which occur every eighteen-point-six years and are the cornerstones of the Celtic calendar. The position of the burials at Magdalenenberg represents a constellation pattern which can be seen between midwinter and midsummer. The positions of the constellations are recalculated back to this period by computer, resulting in a date of midsummer 618 BC, which makes it the earliest and most complete example of a Celtic calendar that is focused on the moon.

c.600 BC :

The first century BC writer, Livy (Titus Livius Patavinus), writes of an invasion into Italy of Celts during the reign of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, king of Rome. As archaeology seems to point to a start date of around 500 BC for the beginning of a serious wave of Celtic incursions into Italy, this event has either been misremembered by later Romans or is an early precursor to the main wave of incursions, probably as a result of the same apparent overpopulation in southern Germany that doubtless forces the start of migration into Iberia around a century earlier. The Celtic advance into the Po Valley also forces the Raeti to relocate into the Alps (according to Pliny the Elder).

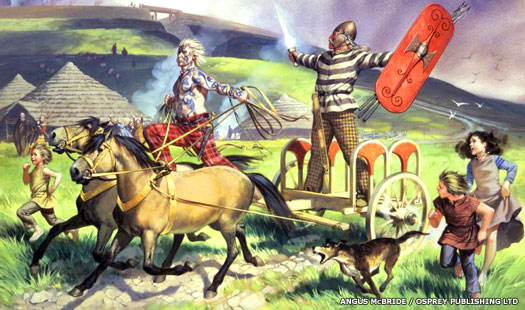

Could it also be linked to the influx of Thraco-Cimmerian migrants along the Danube who have for some time been introducing gradual changes into Celtic society? The influx has seen the gradual replacement of a chariot-borne warrior culture with a lightly armed horse-borne one that is more able to attack larger and more powerful foes.

An idealised illustration of Gauls on an expedition, from A Popular History of France From The Earliest Times Volume I by Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot Livy writes that two centuries before major Celtic attacks take place against Etruscans and Romans in Italy, a first wave of invaders from Gaul fights many battles against the Etruscans who dwell between the Apennines and the Alp. At this time, the Bituriges are the supreme power amongst the Celts (who already occupy a third of the whole of Gaul). They would be a prime example of the new-found dominance of the Hallstatt D tribes of southern Germany, Switzerland, and eastern France, replacing the wealthy Hallstatt C peoples as top dogs

Livy understands that this particular tribe had formerly supplied the king for the whole Celtic race, either suggesting a previously more central governance of the Celts that is now beginning to fragment or the typical assumption that one powerful king rules an entire people. The prosperous and courageous, but now-elderly Ambigatus is the ruler of the Bituriges, and over-population means a division of its number is required. Ambigatus sends his sister's sons, Bellovesus and Segovesus, to settle new lands with enough men behind them to put down any opposition.

Following divination by the druids, Segovesus heads into the Hercynian Forest, on the east bank of the Rhine (this forms the northern border of the lands known to the ancient writers of the Mediterranean, and the modern Black Forest forms its western part). He ends up leading his groups into Carinthia (now in southern Austria) to found the Ambisontes and Ambidravi tribes.

Bellovesus heads towards Italy, inviting fellow settlers to join him from six tribes, the Aeduii, Ambarri, Aulerci, Arverni, Bituriges, Carnutes, and Senones. The body of people led by Bellovesus himself apparently consists mainly of Insubres, a canton (or sub-division) of the Aeduii.

6th century BC :

The Harii probably belong to the Hallstatt culture of Celts, along with the Abrincatui, Bebryces, Boii, Cotini, Helisii, Helveconae, Manimi, Naharvali, Osi, and at least some elements of the later Lugii. They are to be found around the central German lands, and in Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia, and the edges of Poland and Ukraine. Around this time a large-scale expansion begins that sees many Hallstatt Celts migrate outwards, towards northern Italy, Gaul, or Iberia. The Bebryces for one are primarily cattle herders, so they take their herds with them, greatly supplementing their diet with milk, fatty cheese, and beef. Many others remain, and control the region until pressure from newly-arriving Germanic tribes begins to erode their hold in the second and first centuries BC.

The landscape of Bohemia is and was defined by wooded mountainsides and extensive farming land - a green and fertile area at the centre of Europe and of the Hallstatt culture 583 BC :

An archaeological discovery made in the upper reaches of the Danube in 2010 reveals the undisturbed burial of an aristocratic Celtic lady, the so-called 'Celtic princess'. The burial can be dated quite accurately thanks to the preservation in a wet environment of oak flooring in the large grave.

The woman, presumed to have been Celtic nobility, is laid to rest with large amounts of richly decorated gold and amber jewellery. She is aged between thirty and forty years old and has remarkably good teeth. The torso of her skeleton is found still complete, but the head is located three metres away and her lower jaw is in another corner of the burial site. It's still unclear what this means. A child's body is present with her, probably one of her own children, along with another body which may be that of a servant.

The find indicates that the Celts have an aristocratic hierarchy by this period, something which has previously been disputed by archaeologists (peculiarly, given that Indo-Europeans of the Yamnaya Horizon clearly have a warrior class that is in command some three thousand years earlier). The burial objects also reveal some details of Celtic society which have been unknown until now. An ornamental armour for horses is found next to the unidentified woman, but this is not typical of the region. This object may come from northern Italy, whereas other elements come from the south. Celts are therefore involved in more interregional trade than archaeologists have previously thought.

It is the oldest princely female grave discovered to date from the Celtic world, and the only example of an early Celtic princely grave with a wooden chamber. Initially dated to 609 BC, the burial has been recalculated at 583 BC thanks to the very precise dating of the wood, which was taken from a fir tree.

The gold and amber jewellery unearthed from the burial of the 'Celtic princess' show that very high levels of skill were involved in their creation in the first millennium BC c.580 BC :

The major Etruscan centres of Padan Etruria are being founded at this time. This region to the north-east of the Etruscan heartland in Italy is settled up to three hundred years later than the main Etruscan centres, and has a long tradition of interaction with the Celtic tribes to the north that remains largely peaceful until the late fourth century. Epigraphic inscriptions testify to the cohabitation and intermarriage of Celts and Etruscans.

c.500 BC :

Evidence of the spread of Celtic customs and artefacts can be found Britain for this period. More and varied types of pottery are in use, and there is more characteristic decoration of jewellery. There is no known invasion of Britain by the Celts; their arrival is likely to be a more gradual infiltration into existing British society through trade and other contacts over a period of several hundred years, building up settlements starting along the coastline and later migrating inwards. More Celtic settlement can soon be found in Ireland.

To support this influx of Continental Celts, it appears that the R-U152 in Britain can largely be traced to various movements of people from what are today France and Belgium and whose origins are rooted in the Iron Age La Tène Celtic peoples who are now to be found to the west of the Rhine. Some of these peoples would have remained around the heartland of the Seine and Marne and Mosel areas, but between about 500 to 400 BC these areas see a dramatic decrease in population when large numbers migrate to the east to locations in Pomeranian, culture Poland, the modern Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and the Balkans, and east to Ukraine.

c.500 - 335 BC :

The Chiemgau impact (or hypothesis) is a controversial assertion that Central Europe is struck by a meteorite, with the dates used here being the most likely period for that impact. There seems to be a core resistance to its acceptance which dismisses it as 'an obsolete scientific theory', but the evidence to back it up is growing and is rather convincing to an open mind. The location is in Upper Bavaria, part of the heartland of Celtic territory at this time (but also incorporating Vindelici territory), with Lake Chiemsee at its centre. The hypothesis asserts that a large cosmic body (a comet or an asteroid) strikes the ground and leaves a large crater-strewn field with all the relevant impact evidence that such a strike entails.

A strike like this must have a severe effect on the tribes in the region. Much like the Tunguska strike of 1905 and the Tschebarkul 2013 super bolide of Tscheljabinsk in Russia which has been seen far and wide even without the aid of modern communications technology, this strike will be witnessed by a great many people. The means of narrowing the impact date to around 500-335 BC is highly detailed (see the link in the introduction, above), but this would certainly serve to provide a reason for the Gauls being quoted as fearing nothing but the sky falling on their heads (the Asterix strips make especial use of this). In additional, and perhaps coincidentally, it is during this period that the Second Wave migration of P-Celtic speakers begins, with tribes moving outwards from their heartland.

5th century BC :

The Brigantii migrate into the Cispadane Gaul region of the Alps, arriving in an area that has already been settled for a millennium. Strabo later states that they are a sub-tribe of the Vindelici, who occupy territory to the north-east. This could indicate the route taken by the Brigantii to reach their new home, but it also raises the possibility that they are not Gauls, or perhaps only partially so. The Vindelici have an uncertain ancestry, possibly being a blend of Celts and Ligurians (such as the Celto-Ligurian Orobii), making it equally possible that the Brigantii are Ligurians who are commanded by a Gaulish elite. Even referring to the Brigantii as Celts is merely the modern naming convention that has been inherited from the Romans. Thinking of the term as valid or invalid may be irrelevant. 'Celt' may simply be what some West Indo-European speakers call themselves and others not - and with the Celts long in the ascendance in Central Europe, some non-Celtic people may arbitrarily adopt the term in order to fit in.

The arrival of the Brigantii probably causes some disturbance amongst the established native tribes, and very likely some fighting. The Brigantii soon establish a settlement called Brigantion (according to Strabo), which becomes one of their most heavily-fortified locations. No doubt the indigenous tribes still pose a threat.

The Brigantii settlement of Cambodunum, which was located in what is now south-western Bavaria, which was part of the heartland of early Celtic development and culture Like a stone dropped into a pool of water, the Hallstatt Celts have rippled outwards, vastly increasing the territory that is under their influence or control. Now that effect has faded and a new ripple effect is taking its place, generated by the La Tène Celts, who follow the very same path of expansion over the next five-or-so centuries.

5th century BC :

Also dated to the fifth century BC is a Celtic warrior burial that is unearthed by archaeologists in 2014 (discovered in a business zone on the outskirts of Lavau in modern France's Champagne region, close to Troyes). The 'exceptional' grave of this prince is crammed with Greek and possibly Etruscan artefacts. The prince is buried with his chariot in a fourteen-square-metre-large burial chamber, at the heart of a huge mound that itself measures forty metres (130 feet) across, although the mound has not yet been opened.

The biggest find at the site has been a huge wine cauldron. Standing on the handles of the cauldron is the Greek god Acheloos. The river deity is shown with horns, a beard, the ears of a bull, and a triple moustache. Eight lioness heads decorate the cauldron's edge. Inside it, archaeologists have discovered a ceramic wine vessel, called a oniochoe. Other interesting discoveries include a perforated silver spoon that had been part of a set of banqueting utensils, and was presumably used to filter the wine, and the remains of a iron wheel from the chariot that had been buried with the prince.

An Iron Age Celtic prince lay buried with his chariot at the centre of this huge mound in the Champagne region of France, according to the country's National Archaeological Research Institute Trying to pin down the prince's tribe would be highly speculative given that he has been laid to rest around four hundred and fifty years before Julius Caesar records the names of Gaul's tribes in detail. By the first century BC the Champagne region near Troyes is principally occupied by the Tricasses, who have Augusta Tricassium (Troyes) as their oppidum. Nearby tribes include the Catuvellauni and Mandubii, while the larger Lingones lie to the south-east and the mighty Aeduii to the south. The prince would have belonged to a larger collective that has since divided (probably several times) to produce the plethora of first century tribes.

Second

Wave Celts - P-Celtic Speakers (Gauls) / La Tène Culture :

The second wave of Celts was made up of P-Celtic speakers who settled in Gaul, Germania and all points east. These were the Celts of the La Tène culture, which superseded the preceding Hallstatt C culture in southern Germany. How the shift occurred in the Celtic homeland from Hallstatt C to La Tène is the subject of quite a bit of speculation. Overall, it seems most likely that they were heavily influenced by Indo-European migrants ho were arriving in the region by following the Danube from the western shore of the Black Sea. Archaeology has supported such a migratory trail, with such groups perhaps being Thraco-Cimmerians (controversially perhaps), or at least neighbouring groups which were influenced by them through a process of cultural osmosis. At the very least, these newly-arriving Indo-European groups shared the same cultural values, and martial equipment - and probably language too - as the Thracians and Cimmerians, and even Scythians, and it seems to have been they who introduced these changes into the Celtic core homeland.

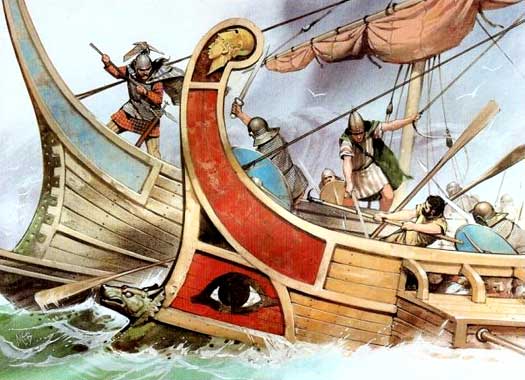

Celts who entered Iberia appear to have arrived by boat to settle the northern and western coasts, such as the tribes of the Astures and Gallaeci. The majority of these Celts were the Gauls who were so well known by Rome. The Romans coined the name 'Galli' ('roosters/cockerals') to describe Celtic tribesmen in general, and this was especially applied to the tribes of what is now central, northern and eastern France. From this was derived the name Gaul. Julius Caesar in his commentaries reports that they called themselves 'Celtae', but they could also be recorded as 'galat', and there are three regions in Europe today that still bear this name, Galatia. Linguistics theory points to a common origin for both forms of the name, along with the German version, 'wealas' or 'wahl' (see main introduction, above).

Once they had settled in modern France, between the seventh and third centuries BC, the Gauls found themselves divided from the newly-arriving Belgae to their north by the Marne and the Seine, and from the indigenous Aquitani to the south by the River Garonne. They also extended eastwards, into the region that was becoming known as Germania. The Celts ruled much of this in their heyday, but by the middle of the first century BC they had become fragmented, and were either in the process of being expelled by the increasingly powerful Germanic tribes who were migrating southwards from Scandinavia and the Baltic coast, or they were being defeated and integrated into Germanic or other tribes.

To an extent this second wave of Celts post-dates the earliest movements of the third wave, that of the Belgae. However, the latter only enter Gaul around the fourth or third centuries at the earliest, perhaps a century or so after the La Tène Celts arrive there, so the established order stands for each of the waves of migration. Details here for the second wave are relatively brief, however, as the majority of their ascendancy parallels that of the Belgae, with both being detailed side-by-side further down the page.

The Suetri were a minor Gaulish tribes of the Alpes Maritimes, with Ptolemy noting their territory being centred around Salinae (modern-day Le Salins). They are also named on the 'Trophy of the Alps', a Roman monument that was erected in 5 BC at the village of La Turbie both to commemorate the conquest of the Alps and the submission of forty-four Ligurian tribes during Augustus' campaigns in 25 BC, 16 BC, and 15 BC and to mark the boundary between Italy and Gaul. The inscription is severely faded on the original monument, but it was recorded by Pliny in his Natural History and records a dedication to Augustus as well as a list of the subdued tribes, amongst whom is the Suetri.

The Tarvisii were another minor Gaulish tribe which, following the Gaulish ingress into northern Italy after 600 BC, found a home on the Venetian plain, somewhat to the north of Venice itself and presumably pushing back the native Adriatic Veneti to do so. The tribal capital was at Treviso, an inland town of the modern Venetia area.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from The La Tene Celtic Belgae Tribes in England: Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R-U152 - Hypothesis C, David K Faux, from Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from? Anne Katrine Gade Kristensen (Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, Hist-fil. Medd 57), from Celts and the Classical World, David Rankin (1996), from The Civilisation of the East, Fritz Hommel (Translated by J H Loewe, Elibron Classic Series, 2005), from Europe Before History, Kristian Kristiansen, from Geography, Ptolemy, from Encyclopaedia of European Peoples, Carl Waldman & Catherine Mason (Facts on File, 2006), and from External Link: The Works of Julius Caesar: Gallic Wars. Other major sources listed in the 'Barbarian Europe' section of the Sources page.)

4th century BC :

The Celts of the La Tène culture begin expanding in all directions. The Boii tribe migrates into the region which forms modern Czechia, giving their name to Bohemia (itself only more recently replaced by the Czech name). It may be the Boii or companion tribes which expand La Tène culture into Silesia where it stops the neighbouring Face-Urn culture from expanding. To the west, the Bellovaci cross the Rhine in this century, settling along the rivers Oise and Somme. They establish fresh sacred sites at Saint-Maur and Gournay-sur-Aronde, and later mint their own coins. The Votadini of eastern Britain also quickly exhibit La Tène burial styles.

In his entry for 53 BC, Julius Caesar writes in his Gallic Wars that there had formerly been a time when the Gauls excelled the Germans in prowess, and waged war on them offensively. On account of the great number of their people and the insufficiency of their land, the Gauls sent colonies over the Rhine. One of these, a division of the powerful Volcae Tectosages, had seized fertile areas of Germany close to the Hercynian Forest, (known to the Greeks as Orcynia), and had settled there.

The Riesengebirge was part of the once-vast Hercynian Forest which spread eastwards from southern Germany and which proved a serious impediment to Roman expansion 389 BC :

Brunnus and his Senones Celts sack Rome, with only the Capitoline Hill standing out against them. The citizens of Rome are forced to pay a thousand pounds in gold to buy off the Celts (a pretty low sum by Roman standards, which perhaps outrages them more than the city being sacked in the first place). This perhaps allows the Etruscans themselves a respite in the incessant pressure from the Latins, although the city of Clevsin is allied to Rome for the duration of the Celtic incursion.

Third

Wave Celts - Belgic Speakers (Belgae) :

The third wave of Celts appears to have been formed of tribes who were seaborne and lived along the North Atlantic and/or Baltic coastlines. Known as the Belgae, they would seem to have been a branch of Celts who established themselves in northern Europe, although precisely where is entirely open to speculation (not to mention some heated debate). The available evidence suggests a general settlement of areas of northern Germany and perhaps northern Poland of the Oxhöft culture too. This break from the main body of proto-Celts could have happened at any time between its first arrival in Central Europe - prior to the twelfth century BC's Urnfield culture of Central Europe - and the height of the Hallstatt culture (c.800-450 BC).

The differences in dialect between the Belgae and La Tène Celts highlights the break, although perhaps it suggests a shorter break than may be indicated by the time periods shown above. The Belgic dialect probably used a 'b' or a 'v' sound where their southern/western cousins in Gaul used a 'w' sound, opening up different interpretations for their names. It is doubtful that all Belgae used the same dialect. Some may have used pure Celtic, some Celtic mixed with various Germanic or even Finnic influences. This alone suggests a wide ranging settlement across Northern Europe, and possibly not even a permanent one. Julius Caesar and other ancient authors certainly saw Germanic elements in many of them, but also affiliations to the Gauls. Those Belgae who were closer to the Rhine would have been less influenced by the proto-Germanic tribes than those who were in modern Denmark or the southern Baltic coast.

For whatever reason, whether it was due to population pressures or movements (the early Germanic tribes being a favourite here as they soon started expanding into Northern Europe themselves), or to climate change, they began to leave (or simply to continue their migratory pattern). Many migrated west after their La Tène cousins had already established themselves in Gaul, probably following the coastline as they went. Others (perhaps even most) seem to have gone east, doubtless following the Baltic coastline (and a theorised third group returned south to become the Taurisci). The western group arrived in the Low Countries and northern Gaul in the fourth and third centuries, although their initial arrival probably took place in the late fifth century. Some of these may not even have travelled beyond the Rhine, remaining in Northern Europe to be progressively Germanised, such as (possibly) the Sicambri and the Semnones. Belgae also landed on the east coast of Britain from about the fourth century BC (or perhaps a little later - providing an exact date is impossible), these groups obviously splitting away from the rest as they reached the Atlantic. These British Belgae slowly infiltrated the south-east of the country so that, by the first century BC, they had formed the Belgae, Cantii, Catuvellauni, Iceni, Parisi, and Trinovantes. The eastern group, known later as the Venedi, reached the Vistula and founded permanent settlements along its east bank, in what the Romans thought of as Sarmatia (with Germania to the west).

Theoretically speaking, the migration away from Northern Europe may also have deposited Belgae in Germany, Bohemia, Moravia and Poland to emerge as the Boii and other similar Central European Celtic tribes. Indeed, it may be the case that the Belgic dialect was simply the Celtic dialect to the east of Gaul and the Rhine - a general 'eastern Celtic' (although the term 'Eastern Celts' could instead be applied to a specific group of Belgae along the Vistula - see feature link, right).

When it comes to determining the meaning of the name 'Belgae', Pokorny gives these roots in Gaulish from a proto-Indo-European base, with the latter's 'bhelg̑h-' and 'bhelg̑h-' descending into Gaulish as 'bolg-' and 'bulga'. The first of these, 'Bhelg̑h-', means to 'swell up'. But the crucial word from this root does not seem to come from Gaulish. Instead it seems to stem from the Anglo-Saxon verb, 'belgan', meaning 'to swell up, or be angry'. This supports the contention that the Belgae were a Celtic-Germanic mix. The Irish description of Cucullaine when his madness is on him comes to mind, swelling up with rage, transforming from a normal man to a monster (apparently borrowed from the Irish for use as the Incredible Hulk!).

However, given the consonant shift proposed above, then 'Belgae' would indicate that its 'b' replaced an older (?) form of a 'w' sound. This supplies 'Welgae' as a possible older form of the name, and rather astonishingly that 'wel-' sounds incredibly similar to what the Germans call Celts! So the possibility is raised that the original ethnic name was 'Wel', and while the Belgae were in northern Central Europe this mutated into 'vel' and then 'bel'; and in the west and south the 'w' of 'wel' acquired a hard 'k' or 'g' in front of it, to form 'kwel' or 'gwel', therefore giving rise to words such as 'celtae' and 'galati' (Galatians). Belgae, minus the Latin plural suffix is 'belg'. If Belgic speech hardened a 'w' sound then 'belg' would have been 'welg'. The 'g' on the end may simply be an '-ig' suffix that is still in use today in Latin and English variants, '-ic' and '-ish' respectively. So Belg would be Belig/Belic. If the Germans adopted their word for Celts from the proposed Celts' own word for themselves, 'wel', then 'belg' (belig) and 'welsh' (waelisc) are exact cognates, the same word in different pronunciations. Whether they were Celts, Belgae, Galatians or Welsh, it was all the same word mutated by several centuries of progress.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from Continuity and Innovation in Religion in the Roman West, R Haeussler, Anthony C King & Phil Andrews, from Liber Prodigiorum, Julius Obsequens, from Periocha, Livy, from Res Gestae, Ammianus Marcellinus, from Valerius Maximus, Pseudo-Quintilian, and Paulus Orosius, from Epitome of Roman History, Florus, Historia Romana, Cassius Dio, from Flavius Eutropius, from Strategemata, Frontinius, from 'Breviary', Sextus Festus, from St Jerome Emiliani (Hieronymus), from Getica, Jordanes, from The Celts in Macedonia and Thrace, G Kazarov, from The Origin of the Gundestrup Cauldron, Antiquity, Vol 61, 1987, A K Bergquist & T Taylor, from The Getae in Southern Dobruja in the Period of the Roman Domination: Archaeological Aspects, S Torbatov, from On the Ocean, Pytheas of Massalia (work lost, but frequently quoted by other ancient authors), from Geography, Ptolemy, and from External Links: Journal of Celtic Studies in Eastern Europe and Asia-Minor, and Scordisci Swords From Northwestern Bulgaria, and The Works of Julius Caesar: Gallic Wars, Perseus Digital Library, and Polybius, Histories, and the Indo-European Etymological Dictionary, J Pokorny, and Geography, Strabo (H C Hamilton & W Falconer, London, 1903, Perseus Online Edition).)

5th century BC :

The Veneti are a tribe (or possibly confederation) of Belgae who occupy a (semi-theoretical) swathe of territory in Northern Europe. Differences in their dialect from the La Tène Celts suggests that they have picked up some influences after settling here, most notably from the proto-Germanic tribes of Scandinavia. Although not universally accepted, generally it is thought that the Belgae begin to migrate around this time, one part heading west towards the Atlantic coast and the other heading east, probably following the Baltic coastline.

Belgic settlement in, or migration across, Northern Europe almost certainly involved some of them entering the Cimbric Peninsula where they interacted with early German tribes there, influencing them and being influenced by them The Atlantic coast division of Belgae settles on territory in the modern southern Netherlands, Belgium, northern France and Brittany (and are termed Veneti for the sake of clarity here). The Baltic division reaches the Vistula and founds permanent settlements along its east bank, in what the Romans later think of as Sarmatia (with Germania to the west). Also for the sake of clarity, they are termed the Venedi.

4th century BC :

According to Julius Caesar, the Belgic tribe of the Atrebates invades northern Gaul from their territory in what would become Germania. They repeat the invasion in the second century, probably to settle there permanently.

c.325 BC :

Pytheas of Massalia undertakes a voyage of exploration to north-western Europe, becoming the first scholar to note details about the Celtic and Germanic tribes there. One of the tribes he records is the Ostinioi - almost certainly the Osismii - who occupy Cape Kabaïon, which is probably pointe de Penmarc'h or pointe du Raz in western Brittany. This means that the tribe has already settled the region by the mid-fourth century, probably alongside their neighbours of later years, the Veneti, Cariosvelites, and Redones.

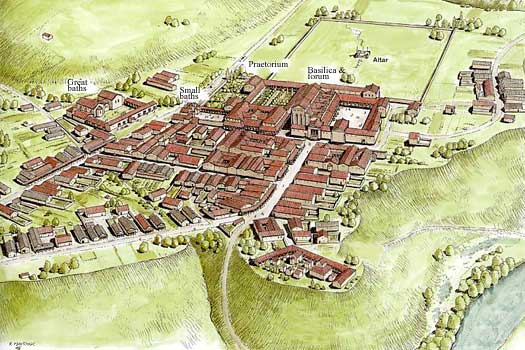

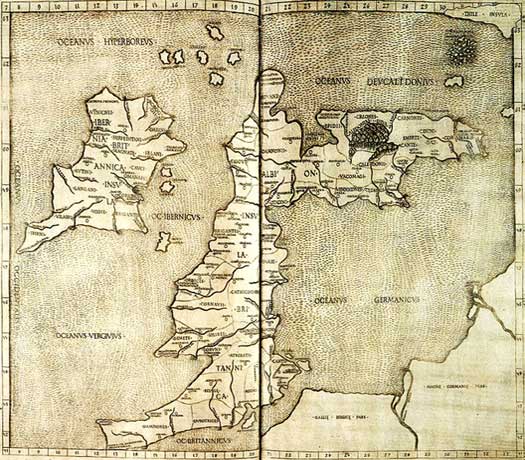

The details recorded by Pytheas were interpreted by Ptolemy in the second century AD, and this 1490 Italian reconstruction of the section covering the British Isles and northern Gaul shows Ptolemy's characteristically lopsided Scotland at the top <c.300 BC :

By this time, a little-known Etruscan city near the modern town of Marzabotto, close to Bologna, has greatly declined. Founded in the sixth century BC, the city had been built on a north-south grid, with paved streets and civic and sacred buildings in the Acropolis. Prosperous until the late fourth century BC, its role suddenly declines to the status of a military outpost following massive Celtic incursions into the Po Valley.

The last stages of Hallstatt culture sees Celts involved in a great expansion into southern and Eastern Europe. Tribes infiltrate across the Danube to enter the land on the southern edge of the Eastern Alps, in the form of the Latovici, Serapili, Sereti, and Taurisci. The native communities in the hinterland of the Adriatic between Carinthia and Carniola are relatively rapidly assimilated by the Celtic newcomers, soon losing their identity completely. The migration turns into a powerful juggernaut as it enters the Balkans to come up against the Thracian and Greek kingdoms in 279-277 BC.

282 - 281 BC :

The Etruscan city of Pupluna suffers badly during Rome's wars against the Boii, this being the group that migrated into Italy in the fourth century BC. Having seen the expulsion by Rome of the Senones in the previous year, the Boii raise a general levy which includes Etruscans and set out to meet the Romans on the battlefield. Near Lake Vadimonis the battle sees the Etruscans suffer the loss of more than half their men, while hardly any of the Boii escape alive.

The following year the Boii and Etruscans try again. This time everyone is armed, including youths who have only just reached manhood. Again they are decimated and completely defeated, and this time they surrender, sending ambassadors to Rome to conclude a treaty. Polybius writes that constant defeats at the hands of the Gauls had inured the Romans to the worst that could befall them, so that they are able to fight the Boii on this occasion like trained and experienced gladiators. The Gauls maintain peace with Rome for forty-five years following this event.

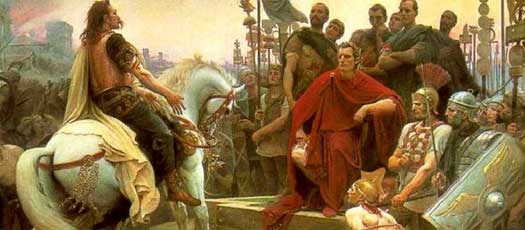

Dictator Marcus Furius Camillus may have been instrumental in persuading Brennus and his Gauls to leave Rome following its sacking in 389 BC, as painted around 1716-20 279 - 277 BC :

Celtic tribes are arriving in the Balkans and Asia Minor by this time. In one encounter with the peoples already there, the Antigonid empire successfully smashes an invasion of Celts into Greece.

Caesar later notes in his journals that 'sometime' before the first century BC the Belgic tribes had emigrated from east of the Rhine. In fact, according to many authors, the archaeological record argues for an earlier date for the first Belgic settlers in northern Gaul. Artefacts of Continental origin which date from the third century BC strongly suggest that the Belgae cross into Britain at about the same time as they settle in northern Gaul. They appear to arrive as fairly small warrior groups that quickly integrate into the elite of the local communities. Other groups seem to remain behind, in northern Germany, to be assimilated by Germans - such as the Marsigni.

Tribes who belong to the Belgae included the Ambiani, Atrebates, Bellovaci, Caleti, Morini, Menapii, Nervii, Remi, Suessiones, Veliocasses, and Viromandui. Caesar states that one tribe, the Atuatuci, are descended from the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones, and describes four others, the Caerosi, Condrusi, Eburones, and Paemani, as German tribes (although Ambiorix, a later leader of the Eburones, has a Celtic name). Other tribes that may be included among the Belgae are the Leuci, Mediomatrici, Treveri, and Tungri. The Remi are the most prominent tribe and their capital, Durocortum (modern Reims in France), becomes the capital of the Roman province of Gallia Belgica.

273 - 214 BC :

The Celts invade Thrace again, destroying the Thracian kingdom and forcing the Greek aristocracy to escape to the colonies bordering the Black Sea. The kingdom of Galatia is created in Thrace by the victorious Celts, only to be destroyed by the Thracians in 214 BC and forced to concentrate itself entirely in Anatolia. The remaining bulk of Celts in the Balkans settles into the powerful Scordisci confederation.

c.250 BC :

Germanic settlements have spread only a little farther south-westwards along the North Sea coastline, and eastwards into the heart of modern Poland and northern Germany. One exception to this is the tribe of the Bastarnae (whose ethnic background is highly uncertain, but evidence tends to support the idea that they are originally Celtic). They have already reached the Balkans by this time.

Between this point and the beginning of the first century AD, Germanic expansion and migration continue this slow progression, extending into modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, and southwards towards modern Switzerland, central Germany, and Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary. All the while, Celtic tribes are being edged out or absorbed.

Many Belgic groups showed marked Germanic influences, so were they Celts with German words and warriors, or Germans with Celtic words and warriors? The truth probably lies somewhere in between 236 BC :

The Gauls in northern Italy have maintained an unbroken peace with Rome for forty-five years, the last battles having being fought against the Boii. A new generation is now in command of the tribes and is eager to test itself against the common enemy. These tribal chiefs inflate trivial excuses in their cause, and invite the Alpine Gauls to join the impending fray.

This is the first that the majority of the tribesmen know of the intended renewal of hostilities, and the Boii immediately form a conspiracy against their own leaders, as well as against the newcomers. A Gaulish king who acts without the support and consent of his own people places considerable risk on his own safety. Atis and Galatus of the Boii are put to death, and the tribe cuts itself to pieces in a pitched battle. Rome, alarmed at the threatened invasion, is able to recall its dispatched army.

232 BC :

Five years after the threat of war between Gauls and Rome had ended in Gaulish internecine battle, during the consulship of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Rome divides the territory of Picenum, from which the Senones had been ejected in 283 BC. For many of the Gauls, and especially the Boii whose lands border this territory, this is an act of war. The tribes are now convinced that Rome wants to destroy and expel them completely.

231 - 225 BC :

Over the next six years or so, the two most extensive tribes, the Boii and Insubres, send out the call for assistance to the tribes living around the Alps and on the Rhone. Rather than each of the tribes sending their own warriors, it appears that individual warriors are hired from the entire Alpine region as mercenaries. Polybius calls them Gaesatae, describing it as a word which means 'serving for hire'. They come with their own kings, Concolitanus and Aneroetes, who have probably been elected from their number in the Celtic fashion.

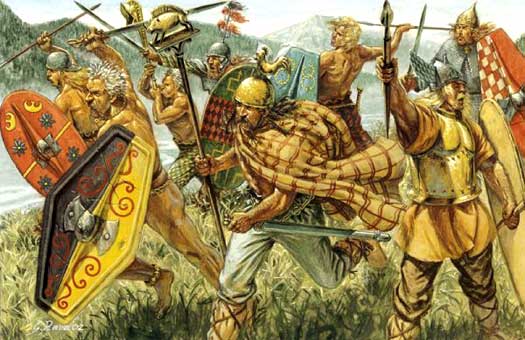

While most of the Gauls of the third century BC fought fully clothed, their Gaesatae mercenaries tended to fight with nothing more than their weapons, and not even the trousers shown here The Gaesatae are offered a large sum of gold on the spot and the wealth of Rome is also pointed out - wealth that can be theirs if they stick to their task. The mercenaries are easily persuaded, and are proud to remind the other Gauls of the campaign that had been undertaken by their own ancestors in which they had seized Rome. This strongly suggests that a proportion of the Gaesatae (probably including their kings) are descended from members of the Senones tribe, as it was this tribe that had led the occupation of Rome in 389 BC.

Rome has been informed of what is coming, and hurries to assemble the legions. Even its ongoing conflict with the Carthaginians take second place, and a treaty is hurriedly agreed with Hasdrubaal, commander in Iberia, which virtually confirms Carthaginian rule there. Such is Rome's haste that they approach the Gaulish frontier before the Gauls have even stirred.

It is 225 BC when the Gaesatae forces cross the Alps and enter the valley of the Padus with a formidable army, furnished with a variety of armour. The Boii, Insubres, and Taurini accompany them but the Cenomani and Veneti are persuaded to side with Rome, forcing the Gauls to detach a force to guard their flank. Despite this, their main army consists of about a hundred and seventy thousand foot and horse, which petrifies the Romans and reminds them of 389 BC. As well as the four new legions, they are accompanied by Etruscans, Sabines, Sarsinates, and Umbri, and more Cenomani and Veneti. Defending Rome and its territories are Ferrentani, Iapygians, Latins, Lucanians, Marrucini, Marsi, Messapians, Samnites, and Vestini, plus two more legions on Sicily and in Tarentum.

The first battle, when it comes, is near Faesulae, outside the subjugated Etruscan city of Clevsin. The Romans are decimated and routed by superior Gaulish tactics. A fresh army under Lucius Aemilius arrives, and Aneroetes counsels retreat with their booty and army intact, ready to launch a fresh attack when ready. Consul Gaius Atilius lands at Pisae with the Sardinian legion and the Gauls find themselves caught between two Roman armies. The battle is fierce, and the Gauls gain the head of Gaius Atilius. However, the battle turns against them and large numbers of Gauls are cut down or taken prisoner, including Concolitanus. Aneroetes is able to flee with his band of followers, and they commit suicide together.

224 BC :

Buoyed by its victory, Rome attempts to clear the entire valley of the Padus. Two legions are sent under the command of the consuls of that year, and the Boii are terrified into submission. However, incessant rain and an outbreak of disease prevents the legions from achieving anything greater.

223 BC :

Two fresh consuls lead two more legions into the Padus, marching through the territory of the Anamares, who live not far from Placentia (some readings of the original text translate this as the Ananes and their home in the Marseilles region, which would be impossible given the nature of this campaign). They secure the friendship of this tribe and cross into the country of the Insubres, near the confluence of the Adua and Padus. Some skirmishing aside, peace is agreed with this tribe, and the Romans head for the River Clusius. There they enter Cenomani lands, with these allies providing some reinforcements. Then the Romans return to the Insubres and begin laying waste to their land. The tribe is faced with no choice but to fight, and their defeat is all but inevitable.

222 BC :

With peaceful overtures by the Insubres being firmly rejected by Rome, the tribe calls on the Gaesatae once more. Together they fight the Romans and withdraw intact to Mediolanum. The stronghold is stormed by the Romans and, following some hard fighting, the Insubres are left with no option but to surrender, their unnamed chief making a complete submission to Rome. This act effectively ends the Gallic War in northern Italy, as Rome now dominates all of the tribes there.

The Celtic tribes of northern Italy were large and dangerous to the Romans, unlike their fellow Celts in the Western Alps, who were relatively small in number and fairly fragmented, although they made up for that by being even more belligerent than their easterly cousins 156 BC :

Having recently defeated the Macedonian kingdom in the Third Macedonian War, Rome appears to be dominant in south-eastern Europe. Little resistance is expected from the various tribes of Greece, Thrace, and the Balkans. And yet it takes a century and-a-half to fully subdue both the hard-fighting Thracian tribes and the Dacians and Celts of the Balkans - especially the Celts of the Scordisci confederation. In this year a minor clash takes place between Rome and the Scordisci, although the details and location are unknown.

c.150 BC :

Metal coinage comes into use in Britain. There is now widespread contact with the Continent through the southern Celtic tribes in the country.

133 BC :

With the fall of the Celtic city of Numantia in Iberia, the Celtiberians are conquered by Rome. To achieve this, it has taken sixty-two years of Roman fighting since the first Celtic submission to them in the Iberian peninsula.

119/117 BC :

Although generally ascribed to 119 BC, Kazarov places this event in 117 BC. After a general period of peace lasting for more than fifteen years, the Scordisci manage to push all the way through the Roman defences in the southern Balkans, reaching the Aegean coast. The Roman governor of Macedonia, Pompeius, is killed during an attack on Argos. A force led by Quaestor Marcus Annius finally ends their adventure, pushing them back. A subsequent attack by the Scordisci together with the Thracian Maedi tribe is also repulsed.

The involvement of the Maedi tribe in the second attack marks the beginning of a new, more widespread involvement in the frequent campaigns between Romans and barbarians. While the Celts in Thrace and the lower Balkans continue to offer the biggest threat to Roman expansion, the native Balkan tribes frequently support them, especially the Bastarnae, Dardani, and the free Thracian tribes (the Bessoi, Denteletes, Maedi, and Triballi). It takes this Macedonian raid to make Rome fully aware of the severity of the threat to its security in the region. The war between Rome and the tribes in the Balkans rumbles on for decades, becoming increasingly bloody and vicious.

113 - 102 BC :

In Franconia, members of the Celto-Germanic Helvetii peoples join a large-scale migration of Germanic Teutones and Cimbri from their homeland in what later becomes central and northern Denmark. The wandering tribes enter Gaul from Germany in 109 BC, causing chaos amongst the Celtic tribes there and rendering critical the situation in the region. It is almost certainly this invasion that sparks a migration of Belgic peoples from the Netherlands and northern Gaul into south-eastern Britain, although such a migration may already have started on a smaller scale.

1st century BC :

By the first century BC the Venedi are known to occupy a great swathe of territory that stretches from East Prussia and modern Kaliningrad, to western Belarus and western Ukraine. They may even have absorbed other Belgic groups that have migrated with them, although the lack of any written evidence makes their history extremely uncertain and open to interpretation.

For a seagoing people like the Belgae, it would have been a fairly simple process to sail along the southern waters of the Baltic and enter a wide river mouth such as the Vistula - settlement quickly followed, spreading south along the river's east bank between the fifth or fourth centuries BC and the first and second AD c.60 BC :

Diviciacus of the Suessiones (not to be confused with Diviciacus of the Aeduii) holds sway not only among a large proportion of the Continental Belgic tribes but also over parts of south-eastern Britain, according to Julius Caesar. This would suggest a form of high kingship over the Belgic tribes that had recently migrated there, such as the Belgae, Cantii, and perhaps the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes. This unity of tribes is reflected in their characteristic triple-tailed horse coins from about 60 BC.

c.60 - 40 BC :

From the latter part of the first century BC and into the next century, various historians mention a variety of tribes and their affiliates which are uniformly identified as being Taurisci, together with a variety of other Cisalpine tribes which include the Norici and Iapydes (not all of which are Celtic in origin). Strabo mentions the Taurisci in his Natural History as being strictly Celtic, as does Livy writing the History of Rome around 10 BC. Pliny the Elder, writing his own Natural History in the mid-first century AD, does the same, along with Apian and Cassius Dio in the second and third centuries AD, saying that the Taurisci are a warrior-like tribe that often plunders Roman territory in the hinterlands of Tergestica (modern Trieste) - this at a time when the various Celtic peoples have largely been Romanised or Germanised.

The other tribes mentioned as individual groups of the Taurisci confederation include: the Carni, who occupy the Carnian Alps, on the edge of the south-eastern Alps; the Latovici between Krka and Sava; the Varciani along the Sava towards Sisak; the Serapili and Sereti along the River Drava on the edge of Pannonia; and the Iasi towards Varadin.

Ancient authors also list several smaller indigenous communities, such as the Illyrian Colapiani along the River Kolpa, the Celtic Ambisontes in the Soča Valley, the Subocrini around Razdrto, and the Rundicti in the Kras and Notranjska regions. The Great Tauriscan tribal community with some identified smaller tribes (such as the Latovici) has never developed into a state formation.

60 - 58 BC :