| DRANGIANA / ZRANKA Incorporating the Ariaspae, Asagarta, Drangians, Sargatians, Thamanaeans, & Utians :

The ancient province of Drangiana lay largely within what is now the easternmost areas of modern Iran, roughly where it meets the border between south-western Afghanistan and western Pakistan, and with a focus on Seistan (Sistan) in Iran. The country is a dusty and often stormy desert with sandy dunes, but there are fertile plains along the River Etymandrus, the modern Helmand Rûd. Prior to its late sixth century BC domination by the Achaemenid Persians, Drangiana seems to have formed part of a much larger and more poorly-defined region known as Ariana, of which the later province of Aria was the heartland. Barely recorded by written history, its precise boundaries are impossible to pin down. It may have encompassed much or all of Transoxiana - the region around the River Oxus (the Amu Darya) - and could have reached as far south as the coastline of the Arabian Sea.

Drangiana or Zarangiana to the Greeks may have been more readily known as Zranka or Zraka to the Persians. The word apparently means 'waterland'. Following its formation into a province, it was bounded to the north by Arachosia, to the east by the Indus region of far western India, to the south by Gedrosia, and to the west by Carmania. As a whole, this region formed the meeting point between Central Asia and South Asia. By the first millennium BC it may have been populated largely by Indo-Iranian tribes which had migrated south across the River Oxus and then expanded to the east and west. Those tribes which remained in the regions immediately to the south of the river appear to enter the historical record around the sixth century BC, when they came up against their cousins from the rapidly expanding Persian empire.

One of those tribes was known as the Drangians, from which the region gained its name. They have also been referred to as the Sarangians, Drangae, and Zarangae, and are claimed as being subjects of the Median empire when this was at its height (although calling it an 'empire' may be a mistaken view of something which may have been more akin to a domination of tribal confederations with the Medes at the top). The Drangians and other tribes in eastern Iran were Indo-Iranians themselves, just like the Medes and Persians. They spoke the same language and had the same customs, such as the fire cult and the cult of the supreme god, Ahuramazda, so they probably would not have viewed Persian rule as an occupation by a foreign power. Breaking down Indo-Iranian tribal names is tricky. The closest finding in Avestan/Old Iranian is dar?g?¯m (adjective); accusative singular neuter 'long'. As for what might be 'long' in the name, this may have to be left as one of history's mysteries for now (possibly the River Etymandrus).

According to Greek historians who documented the campaigns of Alexander the Great, there was also a tribe in Drangiana called the Ariaspae or Ariaspai. They were neighbours of the Gedrosii to their south. Their name is most likely the Latin version of the Greek form, which would be much closer to Ariaspaeoi. Without the Latin or Greek suffix, the name is 'Ariasp', with an unknown meaning that clearly bears a relation to the Arya name (see Ariana for more details). The 'sp' of Ariasp is probably, almost certainly, a contraction with the vowel missing, possibly in the same manner as the 'nt' in the word 'isn't'. Analysis of whether the vowel is missing from the front, back, or middle still awaits. This tribe was also known as 'the Benefactors' because they had saved the army of king Cyrus when it was crossing the desert. Whether the use of 'Drangians' covered a host of local tribes or the Ariaspae were a separate unit is not known, but the Drangians were most likely the most numerous tribe or confederation in the area.

During the Persian conquest of Central Asia, the Drangians were placed in the same district as the Utians or Utii, Thamanaeans (or Thamanaioi), Myci, and Sargatians (Heredotus' Sagartioi, Old Persian Asagarta). Except for the Thamanaeans, who are generally unknown apart from a suspicion that they were also present in Arachosia, and the Myci, who lived in Oman, these tribes can all be found in central Iran. The Sargatians were counted as one of the ten clans of the Parsua but seem to have participated in the rebellion of 521 BC against Darius the Great. In later texts, the Utians are mentioned as inhabiting the Zagros Mountains, to the north of the Persian capitals of Persepolis and Pasargadae, but it is possible that in the sixth century BC, they lived farther to the east and simply followed the migratory path opened up by their Indo-Iranian cousins.

The Utians and many other borderland tribes such as the Cadusii, Gelae (Gelonians or Alans), and Tapuri of northern Media and the shores of the Caspian were classed as Anariaci. The word can be broken down as 'an', meaning 'not', plus 'aria', meaning 'Aryan, Indo-Iranian', and the plural suffix '-ci'. They were the 'not-Indo-Iranians', although the Gelae were indeed Indo-Iranians, if not quite of the same general group as the Persians and Medians. Eventually, though, they were absorbed into the dominant Persian population.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Faramarz, the Sistani Hero: Texts and Traditions of the Faramarzname and the Persian Epic Cycle, Marjolijn van Zutphen, and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Zoroastrian Heritage, K E Eduljee, and Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps), and Livius.org, and Old Iranian - Online Avestan Master Glossary (University of Texas at Austin), and Dictionary of most common Avesta words.)

c.1000 - 900 BC : The Parsua begin to enter Iran, probably by crossing the Iranian plateau to the north of the great central deserts (through Hyrcania) but also by working round to the south of them. Already separated during their journey, Parsua groups head in two main directions. In time the northern groups find themselves in the Zagros Mountains alongside their cousins, the Mannaeans and Medians. They are attested there during the ninth and eighth centuries BC but disappear afterwards. The southern groups, perhaps more numerous, trickle in through Drangiana and Carmania, towards southern Iran and begin to settle there.

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) Located in the Fārs region of Iran, these Parsua come under the overlordship of their once-powerful western neighbour, the kingdom of Elam. In the later stages of Persian settlement, Assyria and Media also claim some control over the region. As Elam's influence weakens, the Parsua begin to assert their own authority in the region, although they remain subjugated by more powerful neighbours for quite some time.

c.620 BC :

The Medians (possibly) take control of Persia from the weakening Assyrians who themselves had only recently taken control of the region from Elam. According to Herodotus, Media governs all of the tribes of the Iranian steppe. This sudden empire may well include territory to the east which covers Hyrcania, Parthia, Drangiana, and Carmania.

c.546 - 540 BC : The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea).

Modern Iran's Makran Coast formed the southern edge of the ancient province of Gedrosia, on what is now the border with south-western Pakistan Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhara, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse.

Persian

Satraps of Zranka (Drangiana) :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Drangiana was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was the easternmost part of the Median empire, who themselves had conquered various fellow Indo-Iranian tribes. The Drangians (Drangae) were based in this region, according to Strabo, while Pliny knew them as the Zarangae. Other sixth century BC tribes in this region were named as the Ariaspae, Sargatians, Thamanaeans, and Utians, all Indo-Iranian tribes (see above for details). Under the Persians, the region was formed into an official satrapy or province which, according to the Behistun inscription of Darius the Great, was called Zranka or Zraka (Drangiana is a Greek mangling of the name).

These eastern regions of the new-found empire were ancestral homelands for the Persians. They formed the Indo-Iranian melting pot from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

The Persians founded a capital for Zranka called Phrada which may be identical to modern Farâh or the Achaemenid palace which was excavated at Dahan-i Ghulaman (near modern Zabol). Gradually during two centuries of Persian domination the region probably changed from one which incorporated a tribal society of cattle drivers to one of committed farmers who often lived in formal villages. One new economic activity was the extraction of tin, which is used to make bronze. By the time the Greeks arrived they could refer to the Drangians as persisontes, which may mean that they were effectively the same as Persians in Greek eyes. Zranka belonged to the satrapty of Harahuwatish (Arachosia) in the Persian period, thanks to Strabo's description of it being situated south of the mountains that enclose Aria. This geographical reference is only comprehensible if Arachosia is understood as a unit which included Zranka. No minor satrapies within Zranka are known.

The minor satrapy of the Ariaspae was autonomous, as was that of the Oritans. Arrian noted the fact that the Ariaspae lived on the River Etymandrus (today's Helmand) - a note that is particularly helpful when locating the province. Even better is the fact that their territory bordered Zranka, Harahuwatish, and Gedrosia.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era, Daniel T Potts, from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, from Ctesias' Persica in its Near Eastern Context, Matt Waters, from Alexander The Great: In the Realm of Evergetǽs, Reza Mehrafarin, and from External Links: The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and The Natural History, Pliny the Elder (John Bostock, Ed), and Livius.org, and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

c.546 - 540 BC : During his campaigns in the east, Cyrus the Great initially takes the northern route from Persis towards Bakhtrish to reassure or subdue the provinces. This route probably involves the 'militaris via' by Rhagai to Parthawa. At some point he takes the more difficult southern route, destroying Capisa along the way (possibly Kapisa on the Koh Daman plain to the north of Kabul - which is possibly also the Kapishakanish named at Behistun as a fortress in Harahuwatish).

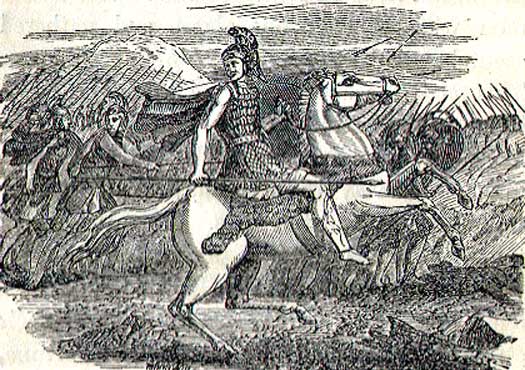

Cyrus the Great freed the Indo-Iranian Parsua people from Median domination to establish a nation that is recognisable to this day, and an empire that provided the basis for the vast territories that were later ruled by Alexander the Great On a fresh leg of the campaign, Cyrus enters the Dasht-i-Lut desert (the modern Dasht-e Loot) on the eastern route out of Karmana towards Harahuwatish. His army faces crippling loses but for the assistance provided by the Ariaspae on the River Helmand. They are named 'the Benefactors' (Greek 'Euergetai') by Cyrus in thanks. This route appears to have been poorly reconnoitred, hinting at a lack of Persian knowledge of this region (and therefore a lack of preceding Median occupation if the existence of its eastern empire is to be believed).

521 BC :

Upon the execution of the Persian usurper, Smerdis, the Cyaxarid, Fravarti, tries to restore the Median kingdom (now the Persian satrapy of Mada). He is defeated by Persian generals and is executed. Darius the Great mentions that the revolt arises in Asagarta, which is the land of the Sargatians within the satrapy of Zranka. The Sargatians are one of the ten clans of the Parsua, raising the possibility that it is some of Darius' own people who oppose him. However, the Sargatians at this time may not be focussed entirely on the Drangiana region. It is possible that they also exist in larger numbers farther west, closer to the Zagros Mountains, and that it may be this group which had raised the flag of rebellion.

The River Oxus - also known over the course of many centuries as the Amu Darya - was used as a demarcation border throughout history and was also a hub of activity in prehistoric times - but during this period it flowed right through the heart of the region that was known as Bactria Ciçantaxma : Rebel who claimed to be a descendant of Cyaxares of Media.

521 BC : The quashing of various simultaneous insurrections from Armina to Parthawa and Verkâna is chronologically coordinated in Persian records and occurs between May and June 521 BC. Ciçantaxma is another Sargatian rebel who meets the same fate as Fravarti after a very quick defeat of his ambitions - mutilated, chained, and eventually impaled at Arbela. Another major rebellion in Mergu happens towards the end of 522 or 521 BC and is quickly crushed.

516 - 515 BC :

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gadara and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka. Along the way the Sakas are largely defeated and conquered, but probably only along the borders.

c.440s - 420s BC :

The placement in Zranka of four satraps, father-and-son duo Hydarnes and Teritoukhames and their two replacements, is highly uncertain but is made possible because a city of Zaris is mentioned in their story. Hydarnes is believed to be a descendant of another Hydarnes, one of the seven who had defeated the Magi and elevated Darius I to the throne in 522 BC. His family becomes important to the Achaemenid succession, with a great deal of intermarriage into the royal line.

Two sides of a drachm showing Darius II (423-404 BC) which was actually issued much later - in the first century BC by the Parthian kings of Iran - and which shows Darius in a Parthian-style tiara adorned with a crescent fl c.440s? BC :

Hydarnes / Idernes : Satrap, with Harahuwatish & Hindush? Died.

fl c.420s? BC :

Teritoukhames / Teritoukhmes : Son. Satrap, with Harahuwatish & Hindush? Killed.

c.420s - 410s BC :

The marriage alliance between Hydarnes and the descendants of Darius I has been important in supporting Darius II in his acquisition of the throne. Upon the death of Hydarnes, his son Teritoukhames has been appointed satrap in his stead (although the name of the satrapy is not given by Photius). Ctesias reports the plot by Teritoukhames to rid himself of his unwanted royal wife so that he can marry his own sister, Rhoxane. Darius has Teritoukhames attacked and killed and Darius' queen, Parysatis, takes violent action against the rest of Teritoukhames' family. There appear to be no survivors other than Stateira, wife of Arsakes (eventually to be Artaxerxes II). Many years later, Parysatis also arranges her death.

fl c.410s? BC :

Oudiastes : Replacement. Satrap, with Harahuwatish & Hindush?

fl c.390s? BC :

Mitradates : Son. Satrap, with Harahuwatish & Hindush? Mitradates opposes the royal court and also his own father and attempts to establish the independent rule of the city of Zaris (Zarin). Again this is assumed to be within the satrapy of Zranka. The prevailing chaos in the Persian court and the great distance between it and Zaris allows the rebellion to establish itself for a short time, forming an independent Achaemenid state.

Artaxerxes II of Persia is immortalised in relief at the entry to his tomb in Persepolis, having survived a reign that began with a series of revolts and included war against the troublesome Greeks (External Link: Creative Commons Licence 2.0 Generic) 360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

? - 330 BC :

Barsaentes : Satrap of Harahuwatish, Hindush, Thatagush & Zranka.

330 - 328 BC :

Barsaentes is one of the three most senior satraps of the east, the others being Bessus in Bakhtrish and Satibarzanes of Haraiva. In 330 BC, Zranka becomes part of the Greek empire despite Bessus' best efforts to retain at least some of the Persian territories as the self-styled 'king of Asia'. His claim is legal, since his satrapy of Bakhtrish is traditionally commanded by the next-in-line to the throne, but Persia has already been lost and his loose collection of eastern allies provides nothing more than a sideshow to the main event - the fall of Achaemenid Persia. Still, it takes Alexander the Great two more years to fully conquer the region.

Barsaentes turns tail when Alexander appears at the border of Zranka and does not wait for him to reach Harahuwatish. Instead he takes refuge in the region of the 'Mountain Indians', a contingent of whom he had commanded at Gaugamela. These facts (probably) indicate that Barsaentes is also responsible for the province of Hindush, the home of the Mountain Indians, and therefore that it is a main satrapy of Harahuwatish.

Argead Dynasty in Drangiana :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Drangiana was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 305 BC.

One of the most informative sources when attempting to reconstruct the satrapal administration of Arachosia and Gedrosia is that of Alexander's appointments. In northern Arachosia, when he first encountered its large administrative complex, Alexander made important decisions about Drangiana, Gedrosia, Northern Indus and Southern Indus. These regions were therefore subsumed in the Arachosian administrative complex. During subsequent years Alexander's many adjustments in this province are not easy to interpret, partly because some of the appointed officers lost their lives during disturbances and through illness. However, the fact that Sibyrtius was satrap of Arachosia and Gedrosia is very good evidence that the two provinces were ruled from Arachosia. The territory of the Ariaspae may also have fallen partially or largely within Gedrosia in the form of a minor satrapy.

The Persian regional capital was renamed by Alexander as Prophthasia, meaning 'anticipation', as it was here that he discovered a plot against him which had been organised, it was said, by his companion, Philotas. The city was also known as Alexandria in Drangiana, but its location was later lost to history. Opinion is divided when it comes to pinning down the most likely candidate. One body of opinion selects Nād-e ʿAlī. Another prefers Farah (Phra), while Zaranj is also in the mix. This last choice can, to an extent, be discounted as it appears on two maps (of 1578 and a thirteenth century copy of a fourth century original) as a distinct entity.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd, G V Shichkina (Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 1994, 8: 83), from A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith (London, 1873), and from External Links: Livius.org, and Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Geography, Strabo (HC Hamilton & W Falconer, Eds, George Bell & Sons, 1903 - Perseus Digital Library).)

330 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

330 - 323 BC :

Arsames : Greek satrap of Aria & Drangiana. Arrested by Stanasor.

323 - 321 BC :

Stasanor the Solian : Greek satrap of Aria & Drangiana. Gained Bactria in 321 BC.

321 BC :

Stasander the Solian is brother to Stasanor, now satrap of Bactria, Chorasmia, and Sogdiana. Perhaps the brother also has more of a focus towards the Northern Indus territories than the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, as later suggested by events. His territory initially extends as far north as Ferghana, which contains the city of Alexandria Eschate ('the Furthest'), while Stasander also has ambitions.

The route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns are shown in this map, with them leading him from Europe to Egypt, into Persia, and across the vastness of eastern Iran as far as the Pamir mountain range 321 - 315 BC :

Stasander the Solian : Greek satrap of Aria & Drangiana (brother of Stanasor).

316 - 315 BC :

The Wars of the Diadochi decide how Alexander the Great's empire is carved up between his generals, but the period is very confused, especially in the east. These provinces appear to be invaded and controlled by the Antigonids for a period, with General Antigonus being responsible for the death of Eudamus. However, at some point in 316 BC, Stasanor the Solian, satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, and Sogdiana (with Ferghana) seizes the Northern Indus while his brother seizes Parthia. Clearly the two are either working in unison with Seleucus of Babylonia from the beginning or are attempting to stamp their own independent authority on much of the east.

315 - 312 BC :

Eumenes is defeated in Asia and is murdered by his own troops, and Seleucus is forced to flee Babylon by Antigonus. The result is that Cassander controls the European territories (including Macedonia), while the Antigonid empire controls those in Asia (Asia Minor, centred on Lycia and extending as far as Susiana), and also temporarily some of the eastern territories, including Aria, Drangiana, and Parthia, where Stasander is removed from office and replaced by Euitus. Unfortunately he dies almost immediately and has to be replaced by Euagoras.

315 BC :

Euitus : Greek satrap of Aria, Drangiana, & Parthia for Antigonus. Died.

315 - 312? BC :

Euagoras : Greek satrap of Aria, Drangiana, & Parthia for Antigonus. Killed.

314 - 311 BC : The Third War of the Diadochi results because the Antigonids have grown too powerful in the eyes of the other generals, so Antigonus is attacked by Ptolemy (of Egypt), Lysimachus (of Phrygia and Thrace), Cassander (of Macedonia), and Seleucus (of Babylonia). The latter does indeed re-secure Babylon itself and the others conclude peace terms with Antigonus in 311 BC.

Eumenes of Cardia, Macedonian general and one of Alexander the Great's 'successors' between whom a series of wars were fought Re-securing Babylon also means recapturing from Antigonus all the eastern territories. Bactria is taken around 312 BC, and it is possibly this event that serves to end the reign of Stasanor. Some areas seem to have been lost to regional warlords, such as parts of Drangiana, but by far the larger part remains under the control of the Greek satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana.

Euagoras attempts to fight Seleucus alongside Nicanor of Media in May 311 BC but he is killed and his men join Seleucus. Then the replenished force goes on to defeat and kill Nicanor and take Media too. Unfortunately the name of the replacement in Drangiana seems to have been lost to history.

312? - ? BC :

? : Unnamed satrap of Aria, Drangiana, & Parthia for Seleucus.

308 - 301 BC :

The Fourth War of the Diadochi soon breaks out. In 306 BC Antigonus proclaims himself king, so the following year the other generals do the same in their domains. Polyperchon, otherwise quiet in his stronghold in the Peloponnese, dies in 303 BC and Cassander of Macedonia claims his territory. The war ends in the death of Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. Seleucus is now king of all Hellenic territory from Syria eastwards, turning Alexander the Great's eastern empire into the Seleucid empire, which includes Drangiana.

Macedonian Drangiana :

The unexpected death of Alexander in 323 BC changed the situation dramatically within his vast Greek empire. Immediately his generals divided the empire between them. Seleucus was able to expand his holdings with some ruthlessness, building up his stock of Alexander's far eastern regions as far as the borders of India and the River Indus (Sindh). Appian's work, The Syrian Wars, provides a detailed list of these regions, which included Arabia, Arachosia, Aria, Armenia, Bactria, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia (as it was known) by 301 BC, Carmania, Cilicia (eventually), Drangiana, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Media, Mesopotamia, Paropamisadae, Parthia, Persis, Sogdiana, and Tapouria (a small satrapy beyond Hyrcania), plus eastern areas of Phrygia.

Once safely under Seleucid control after the conclusion of the Wars of the Diadochi, Drangiana was governed by Macedonian satraps, although details about them are woefully lacking. The capital of Seleucus' new empire was initially at Babylon, the heartland of the former Achaemenid empire that had preceded it, but like that empire, this one contained such a mix of peoples and languages that it was rarely a united entity. Gradual losses of territory over subsequent years drove the Seleucid heartland westwards. The capital had to be transferred to Antioch on the Orontes (Syrian Antioch), which was founded around 300 BC and renamed after one of the later Seleucid kings. More territory was hived away by resurgent subject groups or new empires and the Seleucids were eventually bottled up in Syria, with enemies all around them. Meanwhile the eastern provinces, Carmania included, tended to drift into obscurity as western writers lost sight of them. Only occasional glimpses of events there were recorded, and even some of these must be subject to some analysis.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Encyclopĉdia Britannica, and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991) has been followed.)

206 - 205 BC :

Seleucid ruler Antiochus III returns from his expedition into the eastern regions by passing through the provinces of Arachosia, Drangiana, and Carmania. He arrives in Persis in 205 BC and receives tribute of five hundred talents of silver from the citizens of Gerrha, a mercantile state on the east coast of the Persian Gulf. Having re-established a strong Seleucid presence in the east which includes an array of vassal states, Antiochus now adopts the ancient Achaemenid title of 'great king', which the Greeks copy by referring to him as 'Basileus Megas'.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi 167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes the former province of Aria (now northern Afghanistan) from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. It seems possible that Aria (and possibly a rebellious Drangiana too) had already been conquered once by the Arsacids, with the Greco-Bactrians recapturing it, probably during the reign of Euthydemus I Theos. During the reign of Eucratides I the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

The other eastern provinces, all of which still appear to be in Seleucid hands, must also fall to the Parthians very quickly after this - including Carmania, Gedrosia, and Margiana - although firm evidence to show a specific date appears to be lacking. Another date which may be valid for these losses is 185 BC, when Seleucus IV loses eastern Iran to Parthian expansion, but the fact that the Parthians fail to expand out of their initial conquests until Mithradates accedes makes this period a more likely one.

c.165 BC :

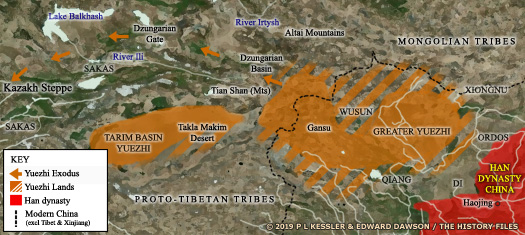

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement.

The Greater Yuezhi were defeated and forced out of the Gansu region by the Xiongnu, and their migratory route into Central Asia is pretty easy to deduct from the fact that they chose to try and settle in the Ili river valley below Lake Balkhash Sakas have long been pressing against Bactria's borders. Now, following a long migration from the borders of the Chinese kingdoms, the Greater Yuezhi start to invade Bactria from Sogdiana to the north. Initially, Saka elements who are already in Bactria become vassals to the Greater Yuezhi.

140 - 130 BC : At around the time of the death of Indo-Greek king Menander in 130 BC, the Greater Yuezhi overrun Bactria and end Greek rule. Heliocles may possibly invade the western part of the Indo-Greek kingdom, as there are strong suggestions that the Eucratids continue to rule there, especially in the form of Heliocles' presumed son, Lysias.

115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhara. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies. Although Carmania doesn't seem to be mentioned directly, its position between Drangiana and Persia would make it likely that this too is still in Parthian hands.

Ruins near Seistan (Sakastan or Drangiana) were probably quite common even by the first two centuries BC, with outposts and cities being occupied and abandoned as the climate changed c.AD 20 :

With the Parthian empire gradually fracturing and collapsing, Gondophares ventures east into recently-captured territory where he establishes an independent Indo-Parthian kingdom in what is now Afghanistan. His kingdom stretches from Arachosia and Gedrosia to northern India, perhaps also with territory within Drangiana. Despite various efforts, Parthian King Artabanus is unable to restore these Indo-Parthians to Parthian control.

c.135 :

Pacores is the last Indo-Parthian king with any real power (in Drangiana and Gandhara especially), and even that does not extend into former core Indo-Parthian territories in Arachosia and Sindh. One more Indo-Parthian king follows him but in diminished circumstances, and virtually unknown to history.

Sakastan (Seistan) :

Around 155 BC, a large section of the Indo-Iranian nomadic Sakas were displaced from Ferghana by the Greater Yuezhi. They were undoubtedly pushed towards neighbouring Sogdiana, where they were dominant enough to take control of the region. This event was connected with the migration of the Greater Yuezhi across Ferghana following defeat by the Wusun and the Xiongnu. The Greater Yuezhi were soon forced to move again, causing other tribes also to be bumped out of position.

The Greater Yuezhi soon managed to force their way into Bactria and, by around 130-120 BC, they snuffed out surviving Greco-Bactrian control there. Around the same time Sakas were also pouring southwards, probably as followers of the Greater Yeuzhi but they soon forced their way westwards seemingly on their own account. With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II was finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeated the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeated the Sakas in Parthia and Drangiana around 100 BC. Saka imperial interests were diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhara, but some Saka inhabitants remained, possibly in great number.

When the Parthian empire faded, the Saka authorities in India were able to push north-westwards to grab further territory such as Arachosia, and possible Drangiana too, reconnecting with the subject Sakas there. By the first century AD the Indo-Parthians had taken over in the region, before the Sassanids secured it from the direction of Iran. But its Saka population had changed the region's identity. The old name of Drangiana appears to have faded out of use (the continuing changes of regime controlling it probably hastened the process). Now it was Sakastan or Seistan - the land of the Sakas (Seistan is a later shortening of Sakastan, but is often used in more modern materials to refer to Sakastan). Around AD 240 the Sassanids created the province of Sakastan or Sijistan out of what had once been Drangiana and the process was complete.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, from A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India, P N Chopra & B N Puri, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from Zāwulistān, Kāwulistān and the Land of Bosi, Domenico Agostini & Sören Stark (Studia Iranica, Tome 45, Fascicule 1, 2016), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps).)

? - 457 :

Peroz : Son of Yazdagird II. Seistan's governor. Gained Sassanid throne.

457 - 459 :

The death of Shah Yazdagird allows his younger son to seize the Sassanid throne ahead of the rightful heir, Peroz. The latter is occupying the position of governor in Seistan (Drangiana) at the time, and instantly seeks the protection of the Hephthalites. Their king, Khushnavaz, is happy to take advantage of Sassanid disunity. Other support comes from the House of Mihran which has already provided the Chosroid kings of Caucasian Iberia, and Peroz is soon able to capture Hormizd. Taloqan is ceded to Khushnavaz in thanks, expanding Hephthalite domains westwards by an extra province.

By the late 400s the eastern sections of the Sassanid empire had been overrun and to an extent occupied by the Hephthalites (Xionites) after they had killed Shah Peroz 459 - ? :

? : Unnamed Sassanid successor in Seistan.

? - 651/2 :

Aparviz : Sassanid governor in Seistan.

652 :

Large areas of the territory (mostly western Afghanistan and large swathes of Chorasmia) are conquered by the Islamic empire as it takes Sassanid Iran, although Kabul remains independent as does neighbouring Zabulistan. At this time the king of Zabulistan is referred to as 'Rtbyl' in Islamic sources. Scholarly speculation that there is more than one person named Rtbyl in Zabulistan would appear to be accurate, with the word perhaps not being a personal name after all. Tarikh-e Sistan of eleventh century Seistan (in Drangiana) provides an extensive account of the wars of a Rutbil of Seistan and Zabulistan against the Muslim conquerors of the region.

In the same period, the son and heir-apparent of the last of the Sassanids, Peroz (Pērōz), has reached the yabgu, the Göktürk viceroy in Tokharistan. From there he soon turns for support to the Tang court. The date of his first embassy to the Tang is before 661, before the formal submission of the yabgu to the Tang after the downfall of the Western Göktürks. A second embassy is received shortly after April 661. With minimal Tang support Peroz is able to continue the battle against the invaders, mostly from Sakastan and Tokharistan.

651/2 - ? :

Rabi ibn Ziyad al-Harithi : Umayyad governor. Later in Greater Khorasan.

666 - ? :

Pacores is the last Indo-Parthian king with any real power (in Drangiana and Gandhara especially), and even that does not extend into former core Indo-Parthian territories in Arachosia and Sindh. One more Indo-Parthian king follows him but in diminished circumstances, and virtually unknown to history.

Tarikh-e Sistan of eleventh century Seistan provides an extensive account of the wars of a Rutbil of Seistan and Zabulistan against the Muslim conquerors of the region. These wars, starting with the confrontation in Sakastan with Islam's Rabi' al-Harithi (Hārithī) in 666, continue well into the ninth century when another Rutbil is defeated by Yaghub bin Laith, founder of the Saffarids of Seistan.

Independent rule of Zabulistan emerged out of Alchon-Nezak control, with their dynasty eventually being succeeded by an entirely native one and with coins such as this crossover type (dated to a period between AD 580-680) no doubt remaining in use c.738 :

The son and successor of Burha Tegin of Kabul is from Kesar who, according to scholars, must ascend the throne of Kabul shortly before 738, although he is possibly a powerful viceroy who is based in the eastern capital of Wayhind in Uddiyana. The coins carrying his name and titles read 'Phromo Kesaro the Mighty (?) the King, the Lord', and 'From Kesar, His Majesty, the Lord, who smote the Arabs', in a countermark, thereby showing his successes in fights against the Islamic empire. It could be speculated that Phromo Kēsaro is either the same as the Rutbil of the Islamic sources, or is the 'Kabulshah' (ruler of Kabul) on whom the Rutbil, the possible series of local rulers of Zabulistan, are relying for their continued fight against the Muslim governors of Sakastan.

Saffarid

Emirs of Seistan (Southern Khorasan) :

In the millennium or so since the death of Alexander the Great, his former satrapy of Drangiana had seen some changes. Invaded by the Indo-Iranian Sakas in the second century BC, Drangiana became the heartland of their new territories in South Asia. It was soon known as Sakastan, the 'land of the Sakas', and this was corrupted over time into Seistan or Sistan.

In the late ninth century AD a Persian commoner by the name of Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar, a coppersmith by trade, remade himself into a warlord. He seized the Seistan region from the ruling Tahirid emirs of Khorasan. Then he quickly and aggressively expanded his holdings both east and west, conquering all of the emirate of Khorasan by the time he died, which included parts of Transoxiana as far as the River Oxus in the north. He also held western and northern areas of what became Afghanistan, territory as far east as the River Indus of India and bordering the kingdom of Zabulistan, and territory to the south, reaching Kerman and Pars. His capital was at Zaranj (Zarang), now in south-western Afghanistan.

Very much a one-man empire, this great sweep of territory was not to remain in Saffarid hands for long. Ya'qub failed to reach Abbasid Baghdad itself (although he came close, and was recognised by the Abbasids in 876 as governor of Seistan as a result). His Saffarid empire was thereafter confined to the eastern parts of Iran. His successor was defeated in battle by the Samanids in AD 900 and had to surrender Khorasan (or Khwarazm as it became better known). Their surviving rump territory lay to the south and west of greater Khorasan but still often bore the same name. Eventually it became an eastern Persian region which was governed separately from the rest of Khorasan and could be better explained as Persian Khorasan.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from the History of Torbat-e-Heydariye, Mohammad Qaneii, from The Cambridge History of Iran, Richard Nelson Frye, William Bayne Fisher, & John Andrew Boyle (Cambridge University Press, 1975), and from External Link: Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

861 - 879 :

Yaghub / Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar : Commoner-turned-warlord. Gave his name to the dynasty.

865 - 873 :

Having already secured his capital of Zaranj at the heart of his small kingdom, Yaghub expands eastwards to capture al-Rukhkhadj and Zamindawar followed by Zunbil and Kabul by 865. Some of his conquests even further east, towards Balk, encompass non- Islamic tribal chiefdoms. Harev (Herat) is taken in 870. Then he expands his borders greatly in 873 by ousting Emir Muhammad of the Tahirids. Khorasan is captured, giving the Saffarids a great swathe of new territory which may also include cities such as Ustrushana to the north of Samarkand.

879 - 901 :

Amr bin Laith / Amir Ibn Layth : Brother. Captured in 900. Executed in Baghdad in 902.

900 :

The Saffarids under the command of Amr bin Laith are defeated by the Transoxianan Samanids at the Battle of Balk. His territory is much reduced, consisting primarily of Seistan itself. The Saffarid princes now remain the vassals of the powerful Samanids who control areas of what is now southern Afghanistan and south-eastern Iran for a considerable period. The Samanids install their own governors in Khorasan.

On Persia's eastern border, India of AD 900 was remarkably unchanged in terms of its general distribution of the larger states - only the names had changed, although now there was a good deal more fracturing and regional rule by minor states or tribes 901 - 908 :

Tahir I ibn Muhammed : Grandson. Never fully in command. Overthrown by Laith.

901 - 905 :

Despite being the recognised emir, Tahir finds himself dominated by his uncle, Laith, and 'Ali, the slave commander Sebük-eri', one of Amr's freedmen after being captured during a Saffarid raid into Zabulistan. Tahir gains Fars in 901 and the city is held by Ali until Tahir is formally granted its governorship in 903 by Caliph Ali Muktafi at Baghdad. By 905, Ali is still in command of Fars and is showing signs of independence. He cuts off the flow of revenue from Fars and Kirman to Tahir. Tahir's lack of finance eventually tells against him when his uncle's patience with him runs out.

908 - 910 :

Laith : Uncle. Captured in battle and sent to Baghdad. Died 929.

909 - 910 :

Laith deals with the rebellious Ali, Sebük-eri', by taking Fars. Ali appeals to the caliph and is aided in recovering Fars. Then he continues the fight against Laith, capturing him in 910. Laith is sent to Baghdad as a prisoner while Ali is confirmed as governor of Fars. In the end Ali is unable to raise the revenue demanded by the caliph and flees eastwards, to be captured and imprisoned until his death in 918.

910 - 912 :

Mohammed I : Brother. Recognised between Seistan and Kabul. Captured.

912 - 913 :

Amr II : Nephew of Tahir. Child figurehead. Replaced Samanid governor.

922 - 963 :

Ahmad I bin Mohammed : Descendant of Amr bin Laith.

963 - 1003 :

Wali-ud-Dawlah Khalaf I / Kalaf : Son. Dethroned by Mahmud of Ghazni. Dynasty extinguished.

1003 :

Khalaf has long been exhibiting irrational behaviour, including the act of putting to death his own son, Tāher. He has largely alienated popular support within Seistan in favour of the Ghaznavids. Yamin-ud-Dawlah Mahmud is now able to march into Seistan, defeat the emir, and carry him off into captivity where he later dies. Seistan now becomes a province of the Ghaznavid empire, and the once-mighty Saffarid house is extinguished. A Ghaznavid governor is put in place in Seistan, becoming the founder of the Nasrids.

This computer-generated image of Ghaznavid regular troops provides a pretty good replica of the real thing which can be somewhat hard to pin down in contemporary illustrations from a region that was in a near-constant state of warfare at this time Nasrid

Emirs of Seistan (Southern Khorasan) :

With the removal of the deeply unpopular and potentially unstable Wali-ud-Dawlah Khalaf of the preceding Saffarid dynasty of emirs, Seistan in Southern Khorasan was safely back under Ghaznavid rule. Or was it? The Seistan region (formerly Sakastan, the 'land of the Sakas', and sometimes shown as Sistan) was politically unstable, along with much of Central Asia and South Asia under the rule of many competing Islamic states. Having retaken the city, the Ghaznavid ruler, Yamin-ud-Dawlah Mahmud, appointed an Iranian Sunni governor named Nasr to Seistan with the title 'malik of Sistan'. However, the death of Mahmud in 1030 ended the dominance of the Ghaznavids. Conflicts soon began to arise between various Ghaznavid claimants, and Nasr soon grabbed his chance to declare an emirate of his own.

Nasr's emirate was based on what is now the Nimruz Province of modern Afghanistan (the country's south-western corner, abutting Iran to the west and what is now Pakistan to the south). Sometimes referred to as the 'Later Saffarids of Seistan', his dynasty is seen as a resurgence of the Saffarid emirate, although it was only a little longer-lasting than the original emirate. This dynasty was also not always independent, being practical enough to serve as vassals of various larger powers who occasionally dominated Seistan. They should not be confused with the Nasrids of Granada who ruled in the thirteenth century.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from the History of Torbat-e-Heydariye, Mohammad Qaneii, from Oriental Coins and Their Values: The World of Islam, Michael Mitchiner (Hawkins Publications, 1977), from Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol 2, André Wink (Brill, 2002), and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Ismaili History.)

1029 - 1073 :

Tadj al-Din I Abu l-Fadl Nasr (I) : Ghaznavid malik of Seistan. Declared independence in 1068.

1040 :

Shihab-ud-Dawlah Masud is unable to preserve his father's empire. Disastrously defeated by Seljuq Turks at the Battle of Dandanqan, he loses the western Ghaznavid territories, including Khwarazm and Seistan. Tughril-Beg is now Tadj al-Din's master.

Shown here is the obverse side of a coin which was issued during the reign of Tadj al-Din I Abu l-Fadl Nasr at Seistan, an important Eastern Iranian city in what is now Afghanistan 1055 :

The Buwayid amirs are defeated by Tughril-Beg of the Seljuq Turks when he conquers Baghdad. With the Buwayids using the Abbasid caliph as the titular head of their empire, the Seljuqs continue the practice.

1059 :

Zahir-ud-Dawlah Ibrahim re-establishes a truncated Ghaznavid empire after the unstable two decades preceding his rule. He agrees peace terms with the Seljuqs and restores cultural and political links, although apparently is not able to restore Ghaznavid dominance of Seistan. However, the empire is increasingly sustained by riches gained in raids across northern India, and the Rajput rulers there offer stiff resistance.

1073 - 1088 :

Baha-ud-Dawlah Tahir (II) : Son. Seljuq vassal.

1088 - 1090 :

Badrha-ud-Dawlah Abu 'l-'Abbas : Brother.

1090 - 1106 :

Baha-ud-Dawlah Khalaf (II) : Brother.

1106 - 1164 :

Tajuddin Nasr (II) : Son of Baha-ud-Dawlah.

1118 :

The death of the Ghaznavid ruler, Masud, in 1115 had triggered a period of instability in his empire to the east. Now Bahram Shah wins the internecine fight with his brothers, but only as a vassal of the Seljuqs. However, the death in the same year of Muhammad Tapar results in the enforced division of Seljuq territory.

1119 :

A vassal of the Seljuq 'Great Sultan', Mahmud II, is one Garshasp II, the Kakuyid emir of the eastern Persian cities of Abarkuh and Yazd. Now disgraced, Mahmud removes him from office by force. Garshasp, however, escapes and returns to Yazd where he requests protection from his brother-in-law, Mahmud's rival in the east, Ahmad Sanjar. Giving Ahmad all sorts of intelligence on Mahmud's defences and forces, Garshasp persuades him to launch an attack on central Persia. Ahmad's coalition army of five kings defeats Mahmud at Saveh. The kings are known to include Garshasp, the emirs of Khwarazm and Seistan, and two others who are unnamed.

The east (Khwarazm and much of Persia) is now under the overall control of Ahmad Sanjar, Mahmud's uncle, although he has already dominated the eastern lands of Persia for many years. Garshasp has been restored to his domains while Mahmud now rules only in Iraq and the westernmost fringes of Persia.

The Seljuq ruler, Ahmad Sanjar, held territory in the wider region of Khorasan while his brother commanded as the 'Great Sultan' in Persia, but Ahmad's dominance of the east increase beyond that of a subsidiary ruler so that, in 1119, he was able to challenge for command of central Persia itself and control of the title of 'Great Sultan' 1162 - 1163 :

A year after recapturing Seistan from the Seljuqs, the death of Sa'if ud-Din Muhammad appears to cause fractures within the Ghurid sultanate, with two rulers appearing, one each in Firuzkuh and Ghazni.

1164 - 1167 :

Shamsuddin Ahmad (II) : Ghurid vassal.

1167 - 1215 :

Tajuddin Harb / Taj-Ud-Din Harb : Son of Muhammad & grandson of Tadj al-Din. Ghurid vassal.

1194 :

The Khwarazm emirate gains independence from the Seljuqs by overthrowing them and occupying much of the rest of Greater Khorasan, including Ghurid Seistan and the heartland of Persia itself.

1215 - 1221 :

Yaminuddin / Shamsuddin Bahram Shah : Son. Killed by Mongols.

1200s :

The Turkic Afshar tribe migrates from Azerbaijan to Southern Khorasan (now northern and western Afghanistan). In time the tribe gains a good grounding in battle tactics in the politically unstable region, and a fighting mentality which stands one of its sons in good stead when he founds the eighteenth century Afsharid dynasty of Persia.

1220 - 1221 :

After the shah of Khwarazm decapitates the Mongol ambassador from Chingiz Khan, the emirate is attacked twice by Chingiz Khan and the Golden Horde, along with Ghurid Afghanistan. Khwarazm is reduced to its western section covering northern Mesopotamia and western Persia. Shamsuddin Bahram Shah of Seistan is killed, and Bukhara and then Samarkand are captured by the Mongols. Chaos results, with thousands being massacred or sold into slavery. As can be expected, Seistan endures a period of instability which is not helped by the sons of Shamsuddin Bahram squabbling over the succession.

1221 :

Nusratuddin / Tajuddin Nasr (III/IV) : Son. Supported by the nobility. Dethroned.

1221 - 1222 :

Ruknuddin Abu-Mansur : Brother. Supported by the rival Ismailis of Kohistan.

1221 - 1222 :

Tajuddin Nasr has proven his enmity towards the Ismailis of Kohistan by upholding his late father's claim on the disputed fortress of Shahanshah. The Ismailis have removed that threat by supporting his brother, Ruknuddin. But in 1222, with Mongols raiding into the region, Ruknuddin is killed by his own slave. Shihabuddin Mahmud is selected by the nobles of Seistan as his successor, to the displeasure of the Ismailis.

Both sides are shown here of a coin that was issued during the brief reign of Tajuddin Nasr in 1221, before he was dethroned by his brother in the turbulent aftermath of the arrival of the Mongols 1222 - 1225 :

Shihabuddin Mahmud (I) : Son of Tajuddin Harb.

1225 :

The Ismailis have another candidate of their own for the governorship of Seistan - Uthman Shah bin Nasiruddin Uthman. They acquire support from a Khwarazmian commander named Tajuddin Yinaltagin who is stationed at Kirman. Yinaltagin arrives at Seistan in 1225 and defeats the local forces but, instead of placing Uthman on the throne, Yinaltagin secures it for himself for almost a decade.

1225 - c.1234 :

Tajuddin Yinaltagin / Inaltigin : Khwarazmian commander and true power in Seistan.

1225 - 1229 :

Abu 'l-Muzaffar Ali (I) : Brother of Ruknuddin. Puppet figurehead.

1229 :

Ala al-Din Ahmad : Brother. Puppet figurehead.

1230 :

Uthman Shah : Brother. Supported by the Ismailis of Kohistan.

1231 - 1235 :

Control over the kingdom of Georgia is reaffirmed by a new Mongol invasion under Ogedei Khan which also overruns the remnants of Khwarazm (centred on modern Azerbaijan). The latter becomes part of Persia and its territories which are under the governance of Tolui. Within a year or so (1235) much of Southern Khorasan is also conquered, including several minor principalities which include the Nasrids of Seistan. In 1236, Shamsuddin Ali of the Mihrabanids is hailed as the city's new malik.

Mihrabanid

Maliks of Seistan (Southern Khorasan) :

The Mihrabanids succeeded the Nasrids as the rulers, or maliks, of the Seistan region, usually under the dominance of greater regional powers. They started off as vassals of the Mongols while the latter were conducting their sweeping conquests of the Far East and Near East and then became vassals of the Il-Khan branch of Mongols. The Mongols had assigned Quhistan to another vassal group, the Sunni Kartids. Quhistan (or Kohistan - meaning 'mountainous land') is now located in the southern part of modern Iran's Khurasan province, a much-reduced far western portion of Greater Khorasan, and so at the very western edge of the thirteenth century region bearing this name, For the sake of clarity the term ' Persian Khorasan' is used to describe this western area. The Kartids soon extended their influence throughout the eastern areas of Persian Khorasan and Southern Khorasan from their seat at Herat.

From Seistan (or Sistan), the indigenous Mihrabanids also increased their power and influence westwards into Quhistan. In fact they did it so well that they eclipsed and succeeded the Kartids there. By 1289, Malik Nasruddin had conquered all of Quhistan and placed his son there, Shams al-Din, as governor (killed in battle in 1306 and succeeded by his own son). Shams al-Din sponsored the poet, Nizari Quhistani, for some years until the latter fell out of favour, was banished, and had his property confiscated. Such territorial expansion was rarely permanent though. At times the Mihrabanids could barely control their own immediate territory, let alone conquer anyone else's. Members of the ruling dynasty's family were often appointed to regional governorships, and usually these governors behaved themselves.

Most of what is known about the Mihrabanids comes from two sources. The first is the Tarikh-i Sistan, which was completed in the mid-fourteenth century by an unknown chronologist and which covers the first hundred years of the dynasty's history. The second is the Ihya' al-muluk, which was written by the seventeenth century author, Malik Shah Husayn ibn Malik Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad, and which covers the entire history of Mihrabanid rule of Seistan.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines, Farhad Daftary, and from The History of the Saffarids of Sistan and the Maliks of Nimruz, C E Bosworth (1994).)

1229 - 1255 :

Shamsuddin Ali II / Shams al-Din 'Ali : Son of Mas'ud. Governor of Kohistan. Hailed as malik in 1236.

1253 - 1258 : Hulegu and his Il-Khan Mongols begin the campaign which sees him enter the Islamic lands of Mesopotamia on behalf of Mongke. Ismailis (assassins) have been threatening the Mongol governors of the western provinces, so Mongke has determined that both they and the Abbasid caliphs must be brought to heel. Hulegu takes Greater Khorasan, and quickly establishes dominion over Mosul. Hulegu's next conquest is Baghdad, in 1258. The caliph and his family are massacred when no army is produced to defend him.

Inheriting the Persian section of the Mongol empire through his father, Tolui, Hulegu Khan led the devastating attack which ended the Islamic caliphate at Baghdad, but he also brought the eastern Persian territories under his firm control (he is seen here with his wife) At the same time (1253), the town of Nih in western Seistan is besieged by Negüder for the Mongols. Shamsuddin leads an army to the defence of Nih and Negüder is defeated. A rebellion breaks out in Seistan in 1255, while he is campaigning in northern Baluchistan, and the Kartid malik of Herat, Shams-uddin, immediately makes the most of the situation by capturing the city himself. Shamsuddin is killed by the rebels, leaving Seistan in the hands of the Kartids until Nasruddin can recapture it in 1261.

1255 - 1328 :

Nasruddin / Nasir al-Din Muhammad : Son. In power from 1261.

1276/77 :

After regaining Seistan from the Kartids of Herat, enforcing his authority over several rebellious towns, and putting down a rebellion by his own chamberlain, Nasruddin still finds that relations with the Il-Khans are rather rocky. Abaqa Khan now invades Seistan, but his army is met by Nasruddin's own veteran forces. The Mihrabanids successfully defend their territory.

1289 :

The Mihrabanids complete their conquest of Quhistan and the Kartid maliks of Herat. Nasruddin appoints his son, Shams al-Din, as governor of Herat. There are times when Shams al-Din must be supported militarily when it comes to holding onto the city, but overall the conquest proves a successful one.

1328 - 1331 :

Nusratuddin / Nusrat al-Din Muhammad : Son. Gained Seistan at the expense of his brother, Rukn.

1331 - 1346 :

Qutbuddin Mohammed II / Qutub al-Din : Nephew. Killed by plague.

1346 - 1350 :

Tajuddin I / Taj al-Din I : Son. Usurped.

1350 - 1362 :

Jalal al-Din Mahmud (II) : Son of Rukn al-Din Mahmud. De facto independent ruler (1357).

1357 :

The Il-Khans collapse. As a result the Mihrabanids gain independence by default and manage to hold onto it for almost half a century. Southern and eastern Persia and Iraq are controlled directly by the Jalayirids until 1401, when a bigger and more powerful opponent arrives on the scene.

Herat's citadel, known as the Qala Ikhtyaruddin or the 'Citadel of Alexander' and conquered by the Mihrabanids in 1289, was founded in 330 BC, although it has been destroyed and rebuilt many times since then 1362 - 1382 :

Izzuddin / Izz al-Din : Brother. Deposed by his own son.

1363 :

The attempts by Tughlugh Temur, Chaghatayid khan of Mughulistan, to quell the tribes of Transoxiana are eventually unsuccessful, despite two invasions of the region. His death ends Chaghatayid hopes of restoring control of western Mughulistan. Instead, two tribal leaders contest for control of Transoxiana. Tîmûr-i Lang (Timur) is ultimately successful, taking Transoxiana and Khorasan in the name of the khanate, but effectively forming his own Timurid khanate.

1380 - 1382 :

Increasingly angry at not being allotted a role in governing the state, Izzuddin's son, Qutbuddin, has sided with a faction which seeks to kill Izzuddin's vizier, someone who exerts a good deal of influence over the malik. Now in 1380 they openly revolt and defeated the malik's army in battle. The Kartids and the malik of Farah straight away invade Seistan and reinstate Izzudin, but the reversal is short-lived. Qutbuddin defeats the invaders and regains full control by the end of the year. His father is exiled and later renounces his title in his son's favour. Over the course of the next year Qutbuddin concentrates on putting down local rebellions against his rule. Having secured his conquests around Transoxiana, Timur has begun the expansion of his territory into Southern Khorasan and Persia. He forces the Kartid dynasty of Herat into submission and demands a hostage from Seistan to symbolise the subservience of the Mihrabanids. Qutbuddin sends a relative named Tajuddin.

1382 - 1383 :

Qutbuddin I / Qutb al-Din I : Son. Captured, imprisoned, and executed by Timur.

1383 :

Despite agreeing a hostage to be sent to Timur in 1382, Timur still turns up at Seistan with his army. The two sides fail to come to agreement so Timur defeats the Mihrabanids in open battle. Qutbuddin is soon captured, imprisoned, and deported to Samarkand. He is executed three years later. Timur appoints Shah-i Shahan as governor of Seistan and proceeds to devastate the province.

Herat's citadel, known as the Qala Ikhtyaruddin or the 'Citadel of Alexander' and conquered by the Mihrabanids in 1289, was founded in 330 BC, although it has been destroyed and rebuilt many times since then 1383 - 1403 :

Tajuddin II / Taj al-Din II / Shah-i Shahan : Son of Mas'ud Shihna. Timur's appointed governor of Seistan.

1403 - 1419 :

Qutbuddin II / Qutb al-Din I : Son of Shams al-Din Shah 'Ali.

1419 - 1438 :

Shamsuddin / Shams al-Din 'Ali : Son.

1438 - 1480 :

Nizamuddin Yahya / Nizam al-Din : Son. Lost Seistan.

1469 - 1501 :

Uzun Hassan of the White Sheep emirate is able to capture Baghdad, along with territories around the Persian Gulf. He expands his emirate into Iran as far east as Herat in Southern Khorasan, replacing the Black Sheep emirs as the main regional power. The emirate is not a single entity, though, having been formed through uniting several clans and tribes in the form of a confederation. Persia's eastern territories regain their independence as the former Timurid empire fragments, including the Mihrabanids, but this generates a fresh wave of regional conflicts as local rulers jostle for supremacy.

1480 - c.1495 :

Shamsuddin Mohd III / Shams al-Din : Son. Unable to regain Seistan - replaced by Mahmud.

c.1495 - 1537 :

Sultan Mahmud ibn Nizam al-Din Yahya : Last Mihrabanid malik. Handed power to the Safavids.

1500 - 1507 :

In this period the Timurids are overthrown by the Shaibanids, who conquer Transoxiana and now threaten Southern Khorasan. The remnants of Khwarazm become an independent Muslim Uzbek state, known as the khanate of Khiva. The Timurid prince, Babur of Ferghana makes many attempts to recapture Samarkand from Khorasan, without success. The Shaibanids now hold much of former Khwarazm, effectively ending Timurid rule of Transoxiana. At the same time Sultan Mahmud regains Seistan from its Timurid commander.

Seistan's traditional territory included the remains of the Timurid-era Shahr-i Ghulghula, a large fortified urban site covering approximately one square kilometre which now lies in Afghanistan's Nimruz Province, to the east of Seistan itself 1537 :

Having previously regained Seistan, Sultan Mahmud now recognises the authority of the Safavids and hands over control of Seistan to Shah Tahmasp I. From the sixteenth century, the former emirate at Seistan generally forms part of an eastern province of Persia. The province continues to be referred to as Khorasan even though it has formed only a small part of the greater emirate of Khorasan and the subsequent region of Greater Khorasan. It frequently also provides a bolt-hole for the defeated participants in various Persian civil wars. It allows them to control the eastern border and still claim to form part of a valid dynasty which can vie for control of the whole of Persia. Generally it can be referred to as Persian Khorasan.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |