| GANDHAR AND PAROPAMISUS The ancient province of Gandhar lay within what is now the easternmost areas of modern Afghanistan and the north of Pakistan. Prior to its late sixth century BC domination by the Achaemenid Persians, the western parts of Gandhar seem to have formed part of a much larger and more poorly-defined region known as Ariana, of which the later province of Aria was the heartland. Barely recorded by written history, its precise boundaries are impossible to pin down. It may have encompassed much or all of Transoxiana, the region around the River Oxus (the Amu Darya), and could have reached as far south as the coastline of the Arabian Sea.

Paropamisus of the Paropamisadae (the Paropamisadai people) seems to have been very close by, but was seemingly not in the same precise region as Gandhar. Gandhar was probably bordered by the River Kokcha (now in Afghanistan), with the Indo-Aryan people of the Paropamisadae on the other, western side of the river and immediately to the east of the Hindu Kush mountains. The Khyber Pass, Kapisa (modern Bagram), Charsadda, and Kabul were all located within this general area. In fact, the region as a whole seems to have been known as Gadara (Gandhar) to the Persians and Paropamisus to the Greeks, both using the different names for the same satrapy.

The city of Kabul may have been founded as a settlement as early as 1500 BC. There are references to it in the Indo-Aryan Rigved scriptures (or Rig Ved - both are correct, and see the feature link, right, for more on the ancient texts), which were probably composed when Indo-Aryan migrants were drifting down into India. During the Indo-Greek period in South Asia, the region was known as Gandhar, and by the time it was conquered by Alexander the Great it was already home to an old Indo-Aryan kingdom of which virtually nothing is known (but see the Gandhari, below). Kabul later became the centre of its own temporarily-powerful kingdom in the early medieval period. Today the city is the largest and most highly-populated city in modern Afghanistan, as well as being its capital.

The Gandhari were a people attested by the Rigved. This was the earliest of the Indian texts to mention them, but later texts also cover them in limited detail, including the Chandogya Upanishad, the Srauta Sutras, and the Aitareya Brahmana. Heinrich Zimmer places them along the River Kubha during India's Vedic period, which is now in eastern Afghanistan, feeding into the River Indus from the Hindu Kush mountains. This suggests that they were amongst the earliest tribes of Indo-Aryans to settle, close to the mountains rather than following the migratory push south-eastwards into India. They are one of the border tribes in the Atharved, along with the Balhikas, both outlying groups (as far as Indo-Aryan settlement is concerned) which were useful as retreats for the fever-stricken. It was here, in their retreat at Gandhar, that they were conquered by the burgeoning Persian empire, probably by Cyrus the Great in his wide-ranging campaigns of 546-540 BC. Their kings are largely legendary, taken from the Vedic texts, and are therefore shown with a plum background.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Abhijit Rajadhyaksha and Edward Dawson, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from Ancient India Part. 1: A Comprehensive History of India, P N Chopra & B N Puri (2005), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Coming into His Own, Heinrich Zimmer (Margaret H Caseand, Ed), from the Vedic Index of Names and Subjects, Vols 1 & 2, Arthur Anthony Macdonell & Arthur Berriedale Keith (John Murray for the Government of India, 1912), from Yājñavalkya, Sureshwar Jha, and from External Links: Encyclopĉdia Britannica, and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

c.4000 BC :

From around this date, proto-Indo-Europeans emerge in Central Asia to form an homogenous people who all speak the same general language. In the third millennium BC, groups begin to migrate west and south, beginning a fragmentation that sees them occupy large swathes of Europe, the Near East, and South Asia.

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) Naganajit : King of the Gandhari (mentioned in Aitareya Brahman).

King Naganajit of the Gandhari is mentioned in the Vedic text, Aitareya Brahman, as a contemporary of King Janak of Videh (not to be confused with the later Janak of the Sunik dynasty Magadh).

Aruddha : Ruler of the Druhyus on the seven rivers.

The Gandhari or Gandhars are also included in the Uttarapath division of Puranic and Buddhistic traditions. The Purans mention the Druhyus being driven out of the land of the seven rivers (immediately to the east of the River Indus) by Mandhatr. The next king of the Druhyus is Gandhar (a convenience to provide an origin for the name of the Gandhari people). He settles his followers to the north-west, on the other side of the Indus, in a land which becomes known as Gandhar, one of the Janapadas (kingdoms) of the Vedic period. In reality, his warband probably enters the region and dominates the Gandhari natives, adding a new ruling elite to their number.

Gandhar : Son and ruler of the Druhyus. Took over the Gandhari.

Pracetas : Later Druhyu successor to Gandhar.

The sons of the later Druhyu king, Pracetas, occupy territory around the Gandhar region and in what is now northern Afghanistan, as mentioned in several of the Puranas - Bhagavat, Brahmand, Matsya, Vayu, and Vishnu. The Gandhars and their king figure prominently as strong allies of the Kurus in their fight against the Pandavs in the Mahabharat war. The Gandhars are apparently a furious people, well-trained in the art of war.

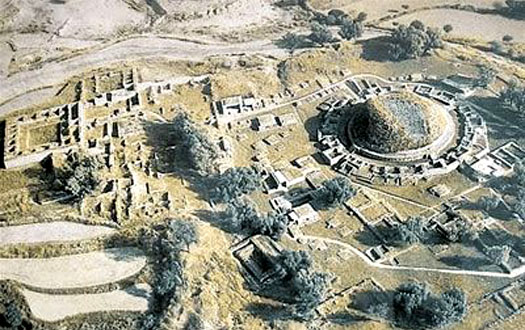

Ancient Gandhar is slowly being explored by archaeologists who constantly unearth relics from several millennia of habitation, possibly including signs of early Indo-Aryan domination here c.546 - 540 BC :

The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea). Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhar (including the Gandhari people and their Druhyu rulers), Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse.

Persian Satraps of Gadara / Paruparasana (Gandhar) :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Gandhar was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was populated by tribal groups, most of whom - by the first millennium BC - would probably have been dominated by Indo-Aryan people, or at least an Indo-Aryan warrior elite which governed an indigenous group. Under the Persians it was formed into an official satrapy or province which, according to the Behistun inscription of Darius the Great, was called Gadara (Gandāra) or Gandara and/or Paruparasana (Gandhar and Paropamisadae are Greek manglings of the name).

These eastern regions of the new-found empire (at least to the north and west of Gadara where Indo-Iranians dominated) were ancestral homelands for the Persians. Those lands formed a melting pot of tribes from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

There is no information about Gadara prior to the arrival of Alexander. This central minor satrapy was presumably governed by an indigenous family for much of the Achaemenid era, and Arrian provides much of the limited detail on them. Astis is the name of the last governor to be installed by the Persians, the only one known from the sources. Various local dynasts mentioned in the sources were presumably subordinates to the satrap himself during the late Achaemenid and early Greek years: Sisicottus, satrap of the Assaceni, Assacanus and his brother who controlled the area around the towns of Massaga and Dyrta, and also Cophaeus and Assagetes.

Two centres of power gravity can be discerned in Gadara upon the arrival of Alexander. One is in the west, in Paruparasana (Paropamisus), which is where Alexander 'founded' the city of Alexandria on the Caucuses and installed a satrap. The other is in the east, where he appointed a second governor who probably had his official seat in Peucelaotis. Paropamisus can be reconstructed as Old Persian *Paraupārisainā (Purushapura, modern Peshawar). This region is not attested in OP texts, where the province is referred to as Gadara. The western part of the satrapy became the more important at the time of Alexander and gave its name to the entire province while it was under Greek rule. This development was dictated by the course of the conquest. After the capture of Paropamisus and an apparent campaign down the southern stretches of the Indus, Alexander turned against Bakhtrish and then, only two years later, continued the conquest south of the Hindu Kush. When the empire was divided up by Alexander's generals at Babylon and Triparadisus, the name was retained: Paropamisadae, so Persian-era Gadara and Paruparasana are essentially east and west halves of the same thing.

The Paropamisadae people themselves were an especially numerous group in their land immediately to the west of Gadara, while Buddhist literature, especially the Jatakas, mentions Taxila as the capital of the 'kingdom of Gandhar'. Under the Persians, the region which encompassed Taxila was formed into an official satrapy or province called Thatagush, but Taxila, on the eastern bank of the River Hydaspes (the modern Jhelum) may have broken away from Gandhar at some point during Persian governance and formed itself into a small but powerful independent kingdom.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, and from External Links: The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

522 - 521 BC :

Immediately after Darius I secures the throne he faces several rebellions, stretching from Babirush to Media and Armina to Parthawa, and Verkâna. The responses to all of these are handled well by Darius and all are crushed in turn. Another major rebellion in Mergu happens towards the end of 522 or 521 BC and that is also put down. In Harahuwatish and Thatagush, the satrap, Vivâna, faces opposition from a rival who has been appointed by the 'usurper'.

The central relief of the North Stairs of the Apadana in Persepolis, now in the Archaeological Museum in Tehran, shows Darius I (the Great) on his royal throne (External Link: Creative Commons Licence 4.0 International) Gadara, perhaps uniquely, seems to be untouched by any of these rebellions. However, there may still be rebel elements in Thatagush, as Darius conducts a campaign there, during which he also seems to secure a new satrapy by the name of Hindush. Some of this territory is already likely to have been part of the conquests of Cyrus the Great, but it is possible that Darius now extends and completes the conquest.

fl c.510s BC :

Bagabadush / Megabazus : Darius I's cousin. Satrap, with Harahuwatish & Thatagush?

516 - 515 BC :

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gadara and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka. Along the way the Sakas are largely defeated and conquered, but probably only along the borders.

In the Behistun inscription's list of satrapies of the empire prior to the accession of Darius, but which are now ruled by him, Gadara is omitted. It has been suggested (by Cook) that this could be for reasons of symmetry in the list's presentation. The Megabazus who governs here could also be the same Megabazus who commands the Persian forces in the west and later becomes satrap of Daskyleion.

fl c.500s BC :

Megabates : Son. Satrap, with Harahuwatish & Paricania.

c.500s BC :

Megabates, son of Megabazus, is father to another Megabazus who in 480 BC is one of the Persian fleet commanders during the campaign against the Greek states. While Herodotus appears not to know where to place Paricania (attributing it to 'Asiatic Ethiopians'), Arrian links it with the Ichthyophagi and Oritans of Gedrosia.

360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

? - 329 BC :

Astis : Satrap.

? - 329 BC :

Bagabādus? : Minor satrap? Otherwise unknown.

? - 329 BC :

Sisicottus : Satrap of the Assaceni. Retained by Alexander.

? - 329 BC :

Assacanus : Satrap (with brother) of Massaga & Dyrta towns. Retained.

? - 329 BC :

Cophaeus : Minor satrap within Gadara. Retained.

? - 329 BC :

Assagetes : Minor satrap within Gadara. Retained.

329 - 327 BC :

Persia is conquered by the Greek empire under Alexander the Great. Persian King Darius III retreats into his eastern territories where he is murdered by Bessus, the satrap of Bakhtrish. Bessus attempts to create a national focus of resistance which soon falls apart, but it takes Alexander two more years to fully conquer the region.

Barsaentes, satrap of Thatagush, Harahuwatish, and Zranka, turns tail when Alexander appears at the border of Zranka and does not wait for him to reach Harahuwatish. Instead he takes refuge in the region of the 'Mountain Indians'. These facts (probably) indicate that Barsaentes is also responsible for the province of Hindush, the home of the Mountain Indians. Alexander campaigns briefly there in 329 BC prior to entering Bakhtrish via the Hindu Kush, crossing Gadara in the process. Barsaentes is eventually captured and handed over to Alexander in 327 BC by King Taxiles in the northern Indus.

Argead Dynasty in Gandhar & Paropamisus :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Gandhar and neighbouring Paropamisadae were left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 312 BC.

There is no information about Gandhar prior to the arrival of Alexander, and Arrian provides much of the limited detail on it. Astis is the name of the last governor to be installed by the Persians, the only one known from the sources. Various local dynasts mentioned in the sources were presumably subordinates to the satrap himself during the late Achaemenid and early Greek years: Sisicottus, satrap of the Assaceni, Assacanus and his brother who controlled the area around the towns of Massaga and Dyrta, and also Cophaeus and Assagetes. They all appear to have been retained under Alexander.

At this time, two centres of power gravity can be discerned. One is in the west, in Paropamisus, which is where Alexander 'founded' the city of Alexandria on the Caucuses and installed a satrap. The other is in the east, where he appointed a second governor who probably had his official seat in Peucelaotis. Paropamisus can be reconstructed as Old Persian *Paraupārisainā. This region is not attested in OP texts, where the province is referred to as Gadara (Gandāra). The western part of the satrapy became the more important at the time of Alexander and gave its name to the entire province under Greek rule. This development was dictated by the course of the conquest. After the capture of Paropamisus and an apparent campaign down the southern stretches of the Indus, Alexander turned against Bakhtrish and then, only two years later, continued the conquest south of the Hindu Kush. When the empire was divided at Babylon and Triparadisus, the name was retained: Paropamisadae, so Gandhar and Paropamisus are essentially one and the same thing.

Buddhist literature, especially the Jatakas, mentions Taxila as the capital of the 'kingdom of Gandhar'. Under the Persians, this region was formed into the official satrapy or province of Thatagush, while Taxila, on the east bank of the River Hydaspes (the modern Jhelum) seems to have broken away from Gandhar at some point during Persian governance, and formed a small but powerful independent kingdom. Its eastern neighbour, Paurav, may also have formed part of Hindush and was now also independent. Both states, in the Northern Indus region, would have to be conquered by Alexander from 327 BC.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from the Mudrarakshasa, Vishakhadatta (Playwright), from the Parishishtaparvan, Acharya Hemachandra, from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, from The Generalship of Alexander the Great, J F C Fuller, from the Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Warfare, J Woronoff & I Spence, from Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Frank Lee Holt, and from External Links: The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and Encyclopaedia Britannica.)

330 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

329 - ? BC :

Sisicottus : Persian satrap of the Assaceni. Retained by Alexander.

329 - ? BC :

Assacanus : Persian satrap (with brother) of Massaga & Dyrta. Retained.

329 - ? BC :

Cophaeus : Persian minor satrap. Retained.

329 - ? BC :

Assagetes : Persian minor satrap. Retained.

327 - 326 BC :

Alexander's army enters western India through the passes of the Hindu Kush, aided by King Ambhi of Taxila on the eastern bank of the River Indus and by the Sakas under Omarg. In support of Ambhi, Alexander fights King Porus of the neighbouring Paurav kingdom, defeating him at the Battle of Hydaspes and then raising both kings as satraps of their respective northern Indus regions. Presumably both are under the administrative gaze of the Greek satrap of northern Indus, Eudamus.

The route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns are shown in this map, with them leading him from Europe to Egypt, into Persia, and across the vastness of eastern Iran as far as the Pamir mountain range 326 - 321 BC :

Oxyartes : Sogdian satrap of Paropamisus. Father of Roxana.

326 BC :

Oxyartes is the father of Roxana, the new bride of Alexander himself. Against the vehemently strong opinions held by his generals, Alexander had proceeded to marry Roxana in 327 BC, while Oxyartes is a Sogdian warlord who had supported Bessus in his attempt to resist Alexander in the east in 329 BC. Oxyartes had subsequently been one of the defeated defenders of the fortress known as the 'Sogdian Rock' in 328 BC, close to the Sogdian capital at Marakanda. In reward for a quick capitulation and for being Alexander's father-in-law, Oxyartes now becomes the satrap of Gandhar.

315 - 305 BC :

Proof of the growing independence of the Greek commanders in the east of the empire is provided by numismatic (coin) evidence. Several local issues of gold, silver, and bronze are struck in the names of independent satraps, including Sophytes (probably of Bactria) and Vakshuvar (sometimes equated with Oxyartes of Paropamisus but possibly his successor instead) between 315-305 BC. It is impossible on the basis of the available evidence to say whether this Sophytes has replaced Stanasor as satrap of Bactria, while the few known coins of Vakshuvar are Persian in style on one side and Greek on the other.

? - 305? BC :

Vakshuvar : Satrap of Paropamisus? Oxyartes himself?

305 - 303 BC :

Following the failure of Seleucus Nicator's Seleucid reconquest of India, the Indo-Greek regions of Paropamisadae, Arachosia, Gandhar, northern Indus, and southern Indus are ceded to the Mauryan empire as part of an alliance agreement. This territory also includes the former kingdoms of Taxila and Paurav in northern Indus. Subsequent relations between the Greeks and the Mauryans appear to be cordial. Seleucus even appoints Megasthenes as his ambassador to Chandragupta's court. The former Indo-Greek territories remain a Mauryan possession until the early years of the second century BC, after which they can be regained by the Greeks.

Macedonian & Mauryan Gandhar & Paropamisus :

The unexpected death of Alexander in 323 BC changed the situation dramatically within his vast empire. Immediately his generals divided the empire between them. During the subsequent war, General Seleucus was able to expand his holdings with some ruthlessness, building up his stock of Alexander's far eastern regions as far as the borders of India and the River Indus. Appian's work, The Syrian Wars, provides a detailed list of these regions, which included Arabia, Arachosia, Aria, Armenia, Bactria, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia (as it was known) by 301 BC, Carmania, Cilicia (eventually), Drangiana, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Media, Mesopotamia, Paropamisadae, Parthia, Persia, Sogdiana, and Tapouria (a small satrapy beyond Hyrcania), plus eastern areas of Phrygia.

By 305 BC Seleucus was fully in charge of the former Greek empire's eastern provinces from his capital at Babylon. In that year he launched a campaign to reconquer India which lasted for two years but which came up against the might of the Mauryan empire and failed to achieve its objectives. Strabo records that Seleucus conceded the later Indo-Greek provinces to the Mauryans as part of an alliance agreement. This included the regions of Arachosia, plus Gandhar and Paropamisadae (essentially the same thing but perhaps divisible into east and west regions respectively), along with northern Indus, and southern Indus. Subsequent relations between the Greeks and the Mauryans were generally cordial, with a Seleucid ambassador appointed to Chandragupta's court.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by David Kelleher, from Life of Apollonius Tyana, Philostratus, from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from The Fragmentary Classicising Historians of the Later Roman Empire, R C Blockley (Francis Cairns, Oxford, 1983), from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, and from External Links: Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991) has been followed.)

fl 206 BC :

Sophagasenos : King in the Kabul Valley (in Paropamisus?).

206 BC :

Seleucid ruler Antiochus III marches from Bactria, across the Hindu Kush, and into the Kabul Valley where he renews ties of friendship with an Indian king by the name of Sophagasenos (alternatively shown as Sophagasenus or Sophagasenas). This king is otherwise completely unknown and cannot be matched with any more certain Indian rulers. Instead, given the location it seems that he may be a local ruler, perhaps in post-Mauryan Paropamisadae before it is seized by the Indo-Greek kingdom around twenty-six years later.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi 185 BC :

Much shrunken since the days of Ashok, the Mauryan empire is overthrown by General Pusyamitra Sunga. The Macedonian kings of Bactria annexe the western half of the empire, including Paropamisadae and Arachosia, advancing as far as the Ganges and the capital at Pataliputra (modern Patna) to form the Indo-Greek kingdom.

c.180 BC :

Placing the death of Demetrius of Bactria (of unknown causes) on this date is generally accepted but far from certain. It is used in an attempt to fit in his death with the subsequent appearance of many successors in several regions of the enlargened kingdom. Some of Demetrius' successors may be co-regents, but civil wars and territorial divisions are very likely. Pantaleon, Antimachus I, Agathocles, and possibly Euthydemus II are all theoretically linked as relatives to Demetrius. In Bactria, Euthydemus II rules, while in the Indo-Greek territories, Agathocles rules in Paropamisadae while Pantaleon rules in Arachosia.

180? - 165? BC :

Agathocles : Bactrian. In Paropamisadae.

180? - 165? BC :

Antimachus I Theos : Brother? In Bactria, Paropamisadae and Arachosia.

c.175 - 160 BC :

Apollodotus I : In Paropamisadae, Arachosia, & Western Indus.

175 - 170/165 BC :

Demetrius II : Son of Antimachus I. In Paropamisadae & Arachosia.

c.175 BC :

Demetrius II rules in Paropamisadae and Arachosia as a sub-king or joint ruler with his father, the Bactrian king, Antimachus I. While he is campaigning in the east, a usurper arises in the west in about 170 BC.

170? BC :

Antimachus of Bactria is apparently defeated by the able newcomer and former general, Eucratides (an alternative is that his territory is absorbed by Eucratides upon his death). Eucratides is opposed by Demetrius II from the Indo-Greek territories. who apparently returns to Bactria with 60,000 men to oust the usurper, but he is defeated and killed in the encounter. Antimachus I also fights against Eucratides, but ultimately is defeated around 160 BC and Eucratides seems to occupy territory as far as the Indus. The Euthydemids are pushed out of Bactria, retaining only the Indo-Greek territories.

The successor to Antimachus I of Bactria was Eucratides I, with this silver tetradrachm being minted in his image at some point during the twenty-six years or so of his reign 171 - c.145 BC :

Eucratides I / Eukratides I : Bactrian. In Paropamisadae, Arachosia, & W Indus.

167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes provinces from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. During the reign of Eucratides the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

c.165 BC :

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement. However, Bactria seems to be at least a decade away from being affected by this, and the Greek kings continue to focus more on their battles against established rivals.

160 - 155 BC :

Antimachus II Nikephoros : In Paropamisadae, Arachosia, & Western Indus.

c.160 BC :

Antimachus II is either the son of Demetrius II or Antimachus I, and serves as co-regent until the deaths of both rulers. It is possible that Apollodotus I becomes the senior ruler until he too dies in 160 BC, at which point Antimachus II heads the kingdom.

c.155 - 130 BC :

Menander I Soter : In Paropamisadae, Western Indus & Eastern Indus (Punjab).

c.155 BC :

In the east, the Indo-Greek king, Menander, seems to repel the invasion by Eucratides, and pushes him back as far as Paropamisadae, thereby consolidating the rule of the Indo-Greek kings in northern India. After this, the Indo-Greek kingdom is permanently divided from Bactria.

c.150 - 145 BC :

Plato : Brother of Eucratides? In Bactria or Paropamisadae.

c.145 BC :

Under pressure in their established homeland thanks to the migration of the Greater Yuezhi, the Sakas enter the territory of Bactria around this time. They burn to the ground the city of Alexandria on the Oxus, an event which seemingly coincides with the death of Eucratides I himself. Generally presumed to be the modern ruins known as Ay Khanum (or Ai Khanum, literally 'Lady Moon' in Uzbek), the city is possibly also known as Eucratidia during its last days - almost certainly thanks to Eucratides I. It goes into unrecoverable decline and today is entirely uninhabited.

Saka Tikrakhauda (otherwise known as 'Scythians' who in this case can be more precisely identified as Sakas) depicted on a frieze at Persepolis in Achaemenid Persia c.130 BC :

At around the time of Menander's death, the Greater Yuezhi overrun Bactria and end Greek rule there, isolating the remaining Greeks east of the Hindu Kush. Heliocles (I) of Bactria may possibly invade the western part of the Indo-Greek kingdom, as there are strong suggestions that the Eucratids continue to rule there, especially in Heliocles' presumed son, Lysias.

There are no historical records of events in the Indo-Greek kingdom after Menander's death, since the Indo-Greeks have by now become very isolated from the rest of the Greco-Roman world. Events from this point are reconstructed almost entirely from archaeological and numismatic analyses.

Zoilus / Zoilos I : Euthydemid? In Paropamisadae & Arachosia.

c.150 - 125? BC : According to numismatic evidence, Zolius rules during the reign of Menander, as the latter king overstrikes two of his coins. Upon Menender's death his queen, Agathokleia, apparently manages to flee east with her child (the future Strato I) in the face of Zoilus' appropriation of much of her husband's realm, and establishes a realm of her own there. Alternatively, Menander himself may previously have relocated east to the Indus (Punjab), where the mint marks on his coins had changed, and this territory is then handed onto his wife and son upon his death.

c.150 - 125? BC :

Agathokleia : Queen. In Paropamisadae & W Indus (Punjab).

c.130 BC :

Thrason : In Paropamisadae, Arachosia, & W Indus (Punjab).

Lysias Aniketos (the Invincible) : In Paropamisadae & Arachosia (& W Indus?).

c.130 - 120 BC : Probably the son of Heliocles I of Bactria, coins for Lysias have been found in the Punjab and it seems likely that he extends his control to both halves of the Indo-Greek kingdom for a period, placing his son as regent in Taxila. This makes understandable the fact that Lysias imitates Demetrius before him, claiming that he is also a conqueror of 'India' - which to the Greeks means Paropamisadae and Indus (Punjab).

c.120 - 110 BC :

Strato I Epiphanes : Son of Menander. In Paropamisadae & W Indus (Punjab).

115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhar. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies. Although Carmania doesn't seem to be mentioned directly, its position between Drangiana and Persia would make it likely that this too is still in Parthian hands.

Two sides of a silver tetradrachm which was issued during the reign of Mithradates the Great of Parthia, with the obverse (left) shown a bearded bust of the king who stabilised the empire's eastern borders with the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi c.115 - 100 BC :

Antialcidas : In Paropamisadae & Arachosia.

110 BC :

The Heliodorus pillar in Vidisha in central India records that the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas sends an ambassador to the court of the Sunga king, Bhagabhadra, at or before this date.

c.110 - 100 BC :

Heliocles II : In Paropamisadae & W Indus (Punjab).

c.100 BC :

Polyxenios : In Paropamisadae & Arachosia.

c.100 BC :

Demetrius III : In Paropamisadae & W Indus. Numismatic evidence only.

100 - 95 BC :

Philoxenus : In Paropamisadae, Arachosia, W & E Indus (Punjab).

c.100 - 70 BC :

Philoxenus briefly rules the whole of the remaining Indo-Greek territory. He may even extend his rule as far as the city of Mathura (in modern Uttar Pradesh), according to an inscription there. From 95 BC the territories fragment again, with the western kings regaining their territory as far west as Arachosia. Some time after 70 BC, Mathura is lost to Indian kings, as is south-eastern Indus (Punjab).

c.95 - 90 BC :

Diomedes : In Paropamisadae.

c.95 - 90 BC :

Amyntas : In Arachosia & Paropamisadae.

c.90 BC :

Theophilos : In Paropamisadae.

c.90 BC :

Peukolaos : In Arachosia & Paropamisadae.

c.90 - 85 BC :

Nicias : In Paropamisadae.

Menander II : In Arachosia & Paropamisadae.

c.90 - 85 BC : The line of alternating rulers in both Arachosia and Paropamisadae and then Paropamisadae alone suggests the possibility that the latter are sub-kings. They are linked to this region by their coin issuances alone, with no surviving written record to back up their status, while any potential agreements or conflicts between the kings is also absent from the historical record. An alternative option is that the Arachosian rulers also occupy part of Paropamisadae and the two sides are in opposition.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahanas of India c.90 - 70 BC :

Hermaeus Soter : In Paropamisadae. Last Indo-Greek king here (to 50 BC?).

c.90 - 70 BC :

Hermaeus, or Hermaios, seems to share the throne with his wife, Kalliope, in the early days of his reign. He pursues an aggressive foreign policy and re-conquers some territories which his predecessors had lost. However, his success is only transitory and the Indo-Greeks find themselves surrounded by powerful enemies. Eventually Hermaios is defeated by the Kushans, bringing to an end any Indo-Greek efforts to regain Paropamisada

c.90 - 70 BC :

Archebios : In Arachosia, Paropamisadae, & W Indus (Punjab).

c.90 - 60 BC :

The Sakas under Maues take control of Indo-Greek Gandhar, creating a capital at Taxila in northern Indus. Gandhar falls within modern southern Afghanistan, part of a region stretching into Persia that remains known as Sakastan or Sistan even today. Taxila is in today's Pakistan. Just forty or so years later, the Kushans capture the same territory from the Sakas in Afghanistan.

c.75 - 70 BC :

Telephos : In Paropamisadae.

c.70 BC :

The Sakas expel the Indo-Greeks from Arachosia but subsequently lose it to the Parthians. Parthian rule seems to be limited and perhaps doesn't include the entire region. Paropamisadae is also permanently lost to the Greater Yuezhi upon the death of Hermaeus Soter.

c.57 - 35 BC :

Azilises : Ruled in Paropamisadae as a joint Saka king with Azes.

The Kushans capture the territory of the Sakas in what is now Afghanistan. They probably also cause the downfall of Indo-Greek King Hermaeus, as they conquer Paropamisadae in the process. The Sakas consolidate their rule in northern India as compensation for the loss of Paropamisadae. They also fight the Satvahans in India, and later enter into matrimonial alliances with them.

A Hermaeus coin from Gandhar at the beginning of the first century AD, which type was copied far and wide, especially by Sakas, Greater Yuezhi, and Kushans - could Hermaeus be the same man as Maues of the Sakas? c.50 BC? : Specific references to Paropamisadae or Gandhar now seem to go quiet. While some activities are known for the Indo-Greeks in general, they are largely confined to the Indus area, not reaching far enough north to concern Paropamisadae. The Kushans are busy becoming the dominant tribe of the Greater Yuezhi confederation, soon beginning the process of uniting the tribes under a single ruler in the process of creating the Kushan empire.

fl c.AD 46 :

Phraotes : In Indo-Parthian Taxila.

c.46 :

The somewhat dubious Phraotes is sometimes equated with the Indo-Parthian King Gondophares. A Greek-speaking Indo-Greek king of Taxila named Phraotes is allegedly met by the Greek philosopher, Apollonius of Tyana, somewhere close to AD 46, although the writer of Apollonius' biography is known to use the name as a stock feature to fill in some of the gaps.

However, despite the Kushan ruler, Kadphises, seemingly inflicting a substantial territorial defeat on the Indo-Parthians around this time, the Indo-Parthians still survive in modern northern India and Pakistan, mainly Sakastan (former Saka territory) and Arachosia, with perhaps tendrils of territory reaching into Gedrosia and even Gandhar and its capital of Taxila where Gondophares may still be ruling.

AD ? :

Theodamus : In Bajaur area of Indo-Parthian Gandhar.

1st century AD :

Theodamus is the last Indo-Greek ruler of any kind to be noted, but only by an inscription on a signet ring. Possibly he governs as a vassal in this last stronghold of Indo-Greek influence in the region - the Bajaur area of Gandhar. Subsequently, Post-Greek Gandhar is largely a location of of Kushan control.

Post-Greek Gandhar & Paropamisus :

The Greek period in Paropamisus lasted a good deal longer than it did in one of the more northerly of the former Achaemenid satrapies - Sogdiana. There Greek rule had ended with the mid-second century BC Saka and Greater Yuezhi invasions. After that it fell almost entirely out of the historical record for several centuries. Gandhar - or Paropamisus in its Greek guise - remained a core part of the Greek Bactrian kingdom and then its successor Indo-Greek state(s) until Indo-Greek rule had been squeezed into extinction by the many later-arriving forces that waxed and waned here.

The Sakas were generally dominant around this time, while the Greater Yuezhi had been consolidating their hold on Bactria and establishing how to govern an already-complex society. By the first century AD one particular faction was becoming the strongest, and this soon led the creation of the Kushan empire which swiftly assumed regional control from the Sakas. They were eventually superseded by the Sassanids from the west, and then governed by the Sassanid vassals, the Kushanshahs. Then the region was hit by waves of invasion by the Xionites, and the cycle continued.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by David Kelleher, from Life of Apollonius Tyana, Philostratus, from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from The Fragmentary Classicising Historians of the Later Roman Empire, R C Blockley (Francis Cairns, Oxford, 1983), from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, and from External Links: Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991) has been followed.)

c.30 - 80 :

The Kushan ruler, Kadphises, subdues the Sakas and establishes his kingdom in Bactria, Gandhar, and the valley of the River Oxus (the Amu Darya). This means defeating the Indo-Parthians and successfully recapturing the main areas of their kingdom, which include Gandhar. The Pahlavas survive in northern India and the Indus region, mainly in Sakastan (former Saka territory) and Arachosia.

This photo illustrates a Kadphises I coin which was discovered in the Bactria-Tokharistan region and which has on it a corrupt Greek legend c.80 - 90 :

Wima Takto, the son of Kujula Kadphises, is for a long time known only to scholars by the Greek legends on his coins - Soter Megas ('the Great Saviour'). However, the translation of an inscription by Kanishka I in Rabatak leads to the discovery that his name is in fact Wima Takto (the 'w' is pronounced in English as a 'v'). His other inscriptions and statues are known from further south and east in India, confirming Kushan control of Gandhar and north-western India.

c.135 :

Pacores is the last Indo-Parthian king with any real power (in Drangiana and Gandhar especially), and even that does not extend into former core Indo-Parthian territories in Arachosia and Sindh. One more Indo-Parthian king follows him but in diminished circumstances, and virtually unknown to history. The Kushans still govern to the south of Gandhar, where they are producing coins in Purushapura (Peshawar) to the south.

c.245 :

Around this year, Shapur I devolves direct Sassanid rule in what is now Afghanistan by creating a buffer state which is governed by the Kushanshahs. They replace the Kushan nobility as the holders of power in the east. Kushanshah coins, initially issued mainly to the north of the Hindu Kush, are also soon to be found to the south in the Begram/Kapiśa area alongside issues by Kushan King Vasishka, suggesting a period of competition between the two sides in this region. With the next Kushanshah, Pēroz I, the Kushanshahs start to displace the later Kushans from Gandhar, confining them to Mathura in northern India, where they are reduced to the status of local princes.

Two sides of a coin issued by Vasudev II around the middle of the third century AD, a gold stater showing the king standing at the altar (on the left), while honouring the Central Asian (Indo-Iranian) goddess, Ardoksho who is seated facing outwards (on the right) c.270 :

In Gandhar, the Kushanshah King Hormazd issues coins, possibly in the names of his governors 'Kavad' and 'Meze' (if these are indeed the names of governors and not titles or something else which remains unknown). It may be that the governor of Gandhar at this time is Vasudev IV, one of the last of the Kushan nobility.

c.325 - c.350 :

With Peroz II of the Kushanshahs beginning to pull away from Sassanid control, the Persian ruler Shapur II divides the realm, assuming direct control of the southern areas of what is now Afghanistan (including Merv in modern Turkmenistan, Herat in Aria, and then Gandhar), while the Kushanshahs continue to rule in the north. With events in the east frequently being poorly documented, there is some doubt about the identity of the Shapur who carries this out. It is probably Shapur II, but it may instead be a governor, or even Shapur's older brother, who bears the same name.

Varhran is the last Kushanshah in Tokharistan and is also a contemporary of Shapur II. Varhran's grip over the Kushanshah territories on both sides of the Hindu Kush is greatly threatened, and it is not long before his realm and power falls to the incoming Kidarites and the expanding reach of Sassanid central power. The control of Gandhar by Shapur II - known through the issue of his copper denomination there - appears to be a side effect of the increased Sassanid interest in the east.

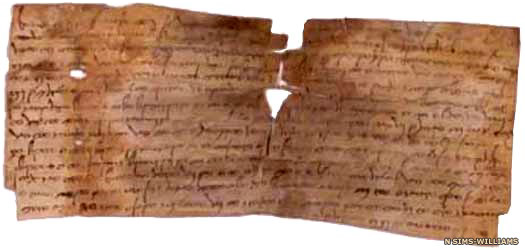

A Kushanshah letter addressed to Varhran from the daughter of a princess named Dukht-anosh, a Middle Persian name c.350 - c.400 :

Peroz III : In Gandhar. A rival claimant or opponent to Sassanid rule?

c.360s - 380s :

Interest in the Kidarites is greatly revived in the early twenty-first century by the discovery of a whole new series of Kidarite copper coins, from the Bhimadevi/Shiva shrine at Kashmir Smast in the mountains of what is now northern Pakistan. The Kidarite leader, Kidara, who is active in the 390s is used to name this group of coins but he is only one of several Xionite rulers in Bactria and Gandhar during the fourth and fifth centuries (albeit it best-known of them). Coinage issues in the names of Kirada, Hanaka, Yosada, and Peroz all appear on coins which are issued before those in the name of Kidara, highlighting several previously unknown Kidarite leaders (Peroz aside). Only approximate dates can be assigned to them, however, as coins usually lack the more precise dating of the written record.

c.375 :

There is no evidence of any Kushans after Kipunada. Having been subjugated by the Gupta kings, the rump eastern Kushan state is soon conquered by the invading Kidarites. They, in turn, claim to be the rightful successors of the Kushans and Kushanshahs. Any possible survivors in the west are probably displaced by the Hephthalites. This is the next wave of barbarians to invade the territory of the Kushanshahs, where they conquer former Bactria and Gandhar to form their own kingdom.

c.390 :

Roman sources mention a specific group of Xionites known as Kidarites. Chinese sources mention a specific name that is assigned to the ruler of this group, one Jiduoluo, interpreted as the Chinese transcription of Ki-da-ra. This particular Hunnic grouping is reported to be located in Gandhar, with its capital at Fu-lou-sha (Old Persian Paraupārisainā (commonly shown as Purushapura), Greek Paropamisus, modern Peshawar).

Bactrian legends on the Kidarite coins issued around this period declare them to represent the 'King of the Kushan'. The Kidarites consider themselves to be the continuation of rule by Kushans and Kushanshahs. A coin type which shows the king in frontal view and wearing a crown with ram's horn has a legend in Brahmi declaring the authority to be 'Sa Piroysa', meaning 'King Peroz'. This is most likely the Peroz III of Gandhar (with his numbering continued from that of the Kushanshahs), the potential rival to Sassanid rule, but possibly only a puppet of the Kidarites.

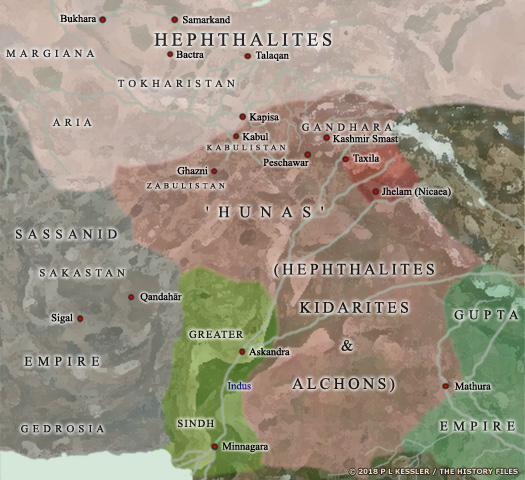

The Kidarites swept into eastern Iran and Tokharistan in the mid-fifth century AD, and by the end of the century they and the other Xionite groups were heavily involved in conquering areas of north-western India, which is where this Kidarite bronze obol with a scorpion was found (in the Kashmir Smast caves), while above is a map covering Turkic origins, with the region around the Altai Mountains seemingly having served as a general incubator c.410 - 565 :

Despite being bordered by the powerful Guptas to the east and the Sassanids to the west. Kushanshah vassal rule of the region is displaced from the north, as the Hephthalites invade and conquer Bactria and Gandhar.

c.430s :

Khingila is the most famous of the Alchon leaders, heading the campaigns in Gandhar which take control of the region from the Kidarites. In the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, he is mentioned as Shengil, where he is considered the king of India. References to other kings called Khingila are made in various sources, such as a garnet seal with the inscription 'Eshkingil the Lord of Rōkan'.

c.455 :

The accession of Kumargupt had seen the continuation of his father's secure Gupta empire under his able rule. However, the last days of his reign are less comfortable, as the empire is threatened by invasions by the Pushyamitras of central India. At a point somewhere around the same time, the Kidarites seize Kabul (in Gandhar) and venture east into Punjab where they reach the kingdom's borders near Doab or Malwa. There they are repulsed by Kumargupt's successor, Skandgupt.

467/468 :

It is Priscus who reports the name of the current Kidarite king as Kunkhas (see Brockley for details). With the Sassanids suffering a seven year famine between 464-471 and unable to launch a serious military offensive, the Kidarites cease making tribute payments. Then both Kunkhas and Shah Peroz attempt diplomacy through trickery until the latter is finally able to go on the attack, possibly motivated by the help rendered to him by the Hephthalites when fighting for his crown against his brother, Hormuzd III. The Kidarites are permanently driven out, finding refuge in Gandhar. The Sassanids may temporarily control the region but it is soon a Hephthalite possession.

484 :

Shah Peroz again chases the Hephthalites out of Bactra in 484 and towards Arion in Aria (Alexandria Ariana, modern Herat). Along the way he destroys the tower built by Bahram V which marks the border between Sassanid and Hephthalite. On the other side of the border, Hephthalite King Khushnavaz sets a trap into which Peroz falls (literally), along with around thirty of his sons and about 100,000 troops. Their bodies are never recovered by the Sassanids.

By the late 400s the eastern sections of the Sassanid empire had been overrun and to an extent occupied by the Hephthalites (Xionites) after they had killed Shah Peroz The eastern empire is overrun and is largely occupied by the Hephthalites until their final fall - this includes regions such as Margiana and its rich capital at Merv, and also much of Gandhar, with the Hephthalites setting up puppet governors. In Kabulistan and Zabulistan the Nezak are able to create their own semi-independent dynasty.

Nezak

Kingdom of Kabulistan & Zabulistan :

The modern city of Kabul may have been founded as a settlement as early as 1500 BC. There are references to it in Rig Ved scriptures which were probably composed when Indo-Aryan migrants were drifting down into India. During the Indo-Greek period in south Asia, the region was known as Gandhar, and by the time it was conquered by Alexander the Great it was already home to an old Indo-Aryan kingdom of which virtually nothing is known. Today Kabul is the largest and most highly-populated city in modern Afghanistan, as well as being its capital.

The Nezak rulers of Kabulistan and Zabulistan emerged as an autonomous power following the death of the Sassanid Shah Peroz in 484. The dynasty they created dominated the regions around the two cities and beyond until the sixth or seventh century when their waning power was replaced by a Turkic dynasty of Kabul shahs which opposed the expanding authority of Muslims that were based further west in Sakastan.

The Xionite invasion of eastern Iran in the fourth and fifth centuries also changed the balance of power in Gandhar. Kabul and the nearby ancient city of Ghanzi (in the region known as Zabulistan) were seized by the Kidarites at a point close to AD 455, following which they were able to venture into Punjab where they came up against the powerful Gupta kingdom in India. Kabul and Zabulistan seemingly remained Kidarite possessions until the Hephthalites achieved domination following their defeat of Shah Peroz.

Some overenthusiastic readings of the Pahlavi phrase 'nycky MLKA' on regional coinage have converted it into the name of an individual Nezak king called Napki Malka, or Nezak Shah. In fact this is based on a misunderstanding of the Middle Persian word 'nycky', meaning 'Nezak; which would have referred to the Nezak dynasty as a whole - the Nezak shahs were the Nezak rulers of the two cities. The use of MLK or MLKA originated with the monotheistic god of Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda (giving the religion its more regional title of Mazdayasna), with 'mazda' meaning 'lord'. By the Middle Persian period it was also being used as a more earthly title in the sense that it referred to a king. Some Sassanid coins of the seventh century show the legend 'MLKAn MLKA', meaning 'king of kings', so it is highly likely that the rulers of Kabul and Zabulistan would have copied this. A single use of MKLA meant that they were realistic enough not to claim to be more powerful than they actually were, and certainly did not see themselves as ruling over other kings.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture, Joseph Kitagawa (Routledge, 2013), and from External Link: The British Museum: Coin Collection Online and Shri Sahi.)

c.530 :

The defeat of the Alchon leader Mihirakula in Malwa around this time signals the end of the 'Huna' involvement in Indian affairs. However, there is no clear indication that the rule of the Alchons in Gandhar and further to the west actually stops with this event. It is presumably following this latest setback that the Alchons retreat back to Gandhar, and possibly even farther west to Kabul.

Following the fall of the Hephthalite empire, Gandhar remained a key stronghold of Xionite power, with several principalities having been established and coin-producing mints springing up to provide vague clues about the existence of their rulers fl c.560 - 620 :

Shri Shahi : Not a name but a rank, found on coinage. This Shri Shahi is known from coins found in Gandhar, but it is a title not a name. The same title is found on a coin dated to the eighth century Shahi kingdom (below). With this being a translation of the Brahmi Sri Sahi, the same title has been found in Bactrian as sri auo, and more tellingly in Pahlavi as 'nspk' MLK'. The last form certainly means Nezak king' (see the introduction above for more detail). Only the most approximate dating can be applied to this king, coming entirely from the coin which bears his title.

565 :

The Hephthalites are defeated by an alliance of Göktürks and the Sassanids, and a level of Indo-Sassanid authority is re-established in the region for the next century. The Western Göktürks set up rival states in Bamiyan, Kabul (seemingly replacing the Nezak kings with their Shahi subjects), and Kapisa under the authority of the viceroy in Tokharistan, strengthening their hold on the Silk Road.

There are further claims for a continuity of Nezak rule in AD 661 and post-679 (see below) but these may be based upon a misunderstanding or a lack of knowledge of the succession of Kabul's rulers. Considering the fact that Nezak-style coins continue to be produced well into the eighth century it is more than likely that the Nezak are not overthrown but instead intermarry and pass on their kingdom to their natural successors.

Shahi

Kingdom of Kabulistan :

Following their success alongside the Sassanids against the Hephthalites, the Western Göktürks secured control of Tokharistan (ancient Bactria). With their own capital lying to the north of the River Oxus, the position of the yabghu of Tokharistan was established (essentially the role of viceroy). This position appears to have provided the Göktürks with a supreme governor for their domains to the south of the Oxus with his authority also being acknowledged to the south of the Hindu Kush, in Kabul and Ghazni (the latter in Zabulistan). In these two cities the original dynasty of Nezak rulers was replaced by that of the Shahis - possibly by two branches of the Shahis from the very beginning, one in each of the cities.

The western Göktürk empire nominally ruled other territories to the south of the Hindu Kush, but these were able to remain virtually independent. Khuttal and Kapisa-Gandhar (Kapisa being the city of Alexandria on the Caucasus, modern Bagram) in the untamed mountainous countryside of what is now northern Pakistan were amongst these independent principalities. Hephthalite or Alchon kings who bore the title xingil in Kapisa-Gandhar continued the coinage of the Hephthalite kings. Several names can be gathered together thanks to this coinage, albeit without any formal idea of dates or order of succession, and these are shown under the Alchon banner.

Later the Shahi kings of Kabul managed to create a fairly extensive empire which stretched eastwards towards the Himalayas. It became known as the Hindu Shahi kingdom (except by the Muslim world), surviving the Islamic empire's conquest of Sassanid Persia in 651-652. Kabulistan and Zabulistan staunchly defended their territory against the Islamic advance for a century, possibly coordinating their efforts with Peroz, the disinherited son and heir of the last of the Sassanid kings, Yazdagird III, who operated in Sakastan and Tokharistan before he was forced to give up the unequal battle and flee to the Tang court between 673-675. His son, Narse, returned from the east to fight on from Tokharistan between 679 and 705-706 before that too fell. Eventually even Kabulistan and Zabulistan fell, being controlled by the Samanid emirate after 900.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE), Khodadad Rezakhani (Touraj Daryaee, Ed, Ancient Iran Series Vol IV, 2017), from The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture, Joseph Kitagawa (Routledge, 2013), from Zāwulistān, Kāwulistān and the Land of Bosi, Domenico Agostini & Sören Stark (Studia Iranica, Tome 45, Fascicule 1, 2016), and from External Links: Coin Archives, and the Turk Shahis in Kabulistan (The Countenance of the Other), and Ancient Coins.)

618 - 630 :

The accession of Tong as the Western Göktürk ruler witnesses a resurgence in the fortunes of the western khagans. He forms a new army, and puts down revolts by the Tiele (Tieh-lê), so that he is able to annexe their lands and extend his domains as far as Gandhar.

In 2012 archaeologists were able to examine the previously-untouched tomb of a Göktürk khagan, which contained amongst many other delights these mounted figurines fl 640 :

? : Khalaj Turk with a branch in Zabulistan.

640 :

The Chinese envoy Xuanzang visits the region and reports that the new ruler of Kabul is a Khalaj Turk. He also states that the family has a branch in Zabulistan, while Bamiyan has its own independent ruler. Huichao, a Korean monk, additionally reports that the area of Uddyana (modern Swat in northern Pakistan) and its population of Alchons is under the control of the king of Jibin (Kabul), supposedly belonging to the new incoming Turkic ruling family or perhaps still in the hands of the Nezak shahs.

652 :

Large areas of the territory (mostly what is now western Afghanistan and large swathes of ancient Chorasmia) are conquered by the Islamic empire as it takes Sassanid Iran, although Kabul remains independent as does neighbouring Zabulistan. At this time the king of Zabulistan is referred to as 'Rtbyl' in Islamic sources, possibly a title rather than a name.

mid-650s :

A king of Kabul - seemingly unnamed but probably Ghar-Ilchi, below - apparently faces off against the young Islamic general, Al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra, in an heroic battle. Kabul's well-provisioned troops are able to hold their own and the two leaders subsequently agree to peaceful coexistence. Al-Muhallab later becomes governor of Khorasan (in 698).

653 - c.661 :

Ghar-Ilchi : Last-known Nezak ruler.

653 - 661 :

According to the Chinese sources, in AD 653 the Chinese emperor formally installs Ghar-ilchi as king of Jibin (Kabul). In 661 the Chinese protectorate of the 'Western Regions' is formed which includes Jibin, and the Tang emperor confirms Ghar-Ilchi him as Kabul's ruler. However, a Turkic dynasty soon reigns in Zabulistan, apparently seizing power in Kabulistan from Ghar-ilchi, the last Nezak king to be known by name. This occurs at a point after AD 661, and perhaps even during 661.

fl 661 :

Hejiezhi : 'Twelfth of the dynasty', possibly including the Nezak in total.

661 :

The Nezak shahs are claimed to have survived on an independent basis until at least this date when, according to Tangshu, a king named Hejiezhi claims to be the twelfth king of a dynasty to rule over Jibin or Kabul. The Nezak branch which rules over Zabulistan probably also survives into the same period in the form of the Late Nezak before succumbing to local Turkic rule.

Two sides of an Alchon-Nezak crossover-type coin dated to a period between AD 580-680 which contains a Nezak-style bust on the obverse (left), and an Alchon tamga within a double border on the reverse (right), displaying the continued close links between the Nezak and the Alchons The claim of the Nezak being in charge of Zabulistan, however, contradicts a claim of 640 that Kabul's ruler is a Khalaj Turk. It may instead be the case that Nezak Kabulistan has passed to this seemingly-locally-formed group of Turks who claim continuity of rule. The local nature of the Nezak and their connection to the Alchons still means that they have survived as local administrators under Göktürk suzerainty, and continue to do so even after the fall of the Göktürks themselves.

Considering the fact that Nezak-style coins continue to be produced well into the eighth century it is more than likely that the Nezak are not overthrown at all but instead intermarry and pass on their kingdom to their natural successors. Hejiezhi, though, could be same same person as Ghar-Ilchi, with the Turkic takeover coming around AD 665-666. Once it does, under the leadership of Barha Tegin the administrative and royal centre is moved from Kapisa (Begram) to Kabul.

fl 666 - c.687? :

Burha Tegin : Issuer of the 'Tegin coins' post-679.

666 :

Scholarly speculation that there is more than one person named 'Rtbyl' in Zabulistan would appear to be accurate, with the word perhaps not being a personal name after all. Tarikh-e Sistan of eleventh century Seistan provides an extensive account of the wars of a Rutbil of Seistan and Zabulistan against the Muslim conquerors of the region. These wars, starting with the confrontation in Sakastan with Islam's Rabi' al-Harithi (Hārithī) in 666, continue well into the ninth century when the Rutbil at the time is defeated by Yaghub bin Laith, founder of the Saffarids of Seistan.

At the same time this Rutbil himself (or themselves) use the kingdom of Kabul for refuge. Whenever the Rutbil is pressured or forced into an alliance, he heads towards the north and east, to upper Zabulistan and Kabulistan, and seems to have a huge reserve of money and soldiers either to buy off or to fend off the Muslims (for the latter, see AD 650s as a first instance of this). AD 665 or 666 is the date for the first Arab raid to reach Kabul, although it is quickly fended off. The source of this wealth lies in Kabul while, lying essentially to the north of Zabulistan, the little-known kingdom of Rob may be an appendage.

This silver drachm which was issued by Tegin is remarkable for being trilingual carrying legends in Greco-Bactrian, Pahlavi, and Brahmi which illustrates the growing influence of the issuing body post-679 :

Coins issued by one Tegin which can be dated to the immediate post-679 period bear the inscription 'His perfection, Tegin, King'. This Tegin is most likely the same as Burha Tegin, named as the founder of the Turki-shahi dynasty of Kabul by Al-Biruni (providing yet another date for the replacement of the Nezak rulers after 640 and 661). He is claimed as the reason for the Arabs being expelled from Kabul in 666 and, according to Gyselen, is succeeded by Rutbil of Zabulistan in the 680s. One Tegin coin is related to a later type which is issued after 687, with a Pahlavi inscription of 'Tegin, His Majesty, Lord, King of Khorasan', but bearing a mint signature of 'Zabulistan.

c.687? - ? :

'Rutbil' : Successor. King of Zabulistan since 660s.

fl 693 :

? : Uncle of the king of Zabulistan.

693 :

Perhaps one of the earliest mentions of the ruler of Kabul is through the 'Ser' of the Göktürks in the Bactrian Documents (BD S) which are written in Bactrian Era 470 (AD 693). A series of coins with the title of Sero also appear around this time alongside the Pahlavi 'nycky MLKA', which further strengthens this identification and can be assigned to the Kabul region. At the same time, a Zabulistan branch of Kabul's ruling dynasty can also be seen to exist, based on Chinese sources which assert that the king of Zabulistan is a nephew of the king of Kabul.

c.738 :

Tegin's son and successor is from Kesar who, according to scholars, must ascend the throne of Kabul shortly before 738, although he is possibly a powerful viceroy who is based in the eastern capital of Wayhind in Uddiyana. The coins carrying his name and titles in Bactrian, and sometimes Brahmi, read 'Phromo Kesaro the Mighty (?) the King, the Lord'. His actual name could be the well-known name Zawāra, mentioned in the Shahnameh as the brother of the hero Rostam.

c.738 - ? :

Zawāra? 'Phromo Kesaro' : Son of Burha Tegin. On the obverse of one type of his coins, 'Phromo Kesaro' refers to himself as 'From Kesar, His Majesty, the Lord, who smote the Arabs', in a countermark, thereby showing his successes in fights against the Islamic empire. Considering the mint mark of z'wl (Zabul) on at least one type (247), it could be speculated that Phromo Kēsaro is either the same as the Rutbil of the Islamic sources, or is the Kabulshah (ruler of Kabul) on whom the Rutbil, the possible series of local rulers of Zabulistan, are relying for their continued fight against the Muslim governors of Sakastan.

Shown here are the two sides of a coin that was issued by Phromo Kesaro, although the dating can vary widely from that shown above for this king - even the late seventh century is sometimes claimed for his rule of Kabul 700s :

Vipilind? : Known only from a single coin. A single gold dinar mentions one 'Vipilind', an otherwise unknown ruler of the eighth century (the dating cannot be any more precise than this). The coin has on it the Sarada legend, 'Shri Shahi' ('Nezak king' - see the Kabulistan Nezaks for additional detail), clockwise above and Vipilinda anticlockwise below. This is probably the earliest example of a Shahi 'Bull and Horseman' type coin to be struck in gold to the 'dinar' standard. Palaeography of the legend suggests its dating, when Brahmi is gradually being transformed into Sarada script. The name of the issuer, 'Vipilinda', could be the governor of the mint which issues the coin, although the king's name is more likely.

c.820 :

Devapal of the Pala kings of north-eastern India counts as his military successes the conquest of Pragjyotisha (Assam), where the king submits without a fight, and the Utkalas, whose king flees from his capital city. But he is also claimed as having routed the Hunas, seemingly late for such a victory. Could this be a raid by the Hephthalites or Alchons who are still in the Gandhar region?

821 :

The Tahirid emirs are established in Khorasan to the north-west when the region is granted to them by the Abbasid caliph, al-Mamun.

873 :

The Tahirids are ousted as emirs of Khorasan by the Saffarids. The Saffarid dynasty founder, Yaghub, now dominates Kabul and Zabul, along with a great swathe of other territory in South Asia.

900 :

Much of Saffarid Khorasan is conquered by the Transoxianan Samanid emirate while the Buwayid amirs gain control of western Persia. This territory includes Zabulistan with its capital at Ghazni, and it is this area that emerges as the main focal point for control of the entire region.

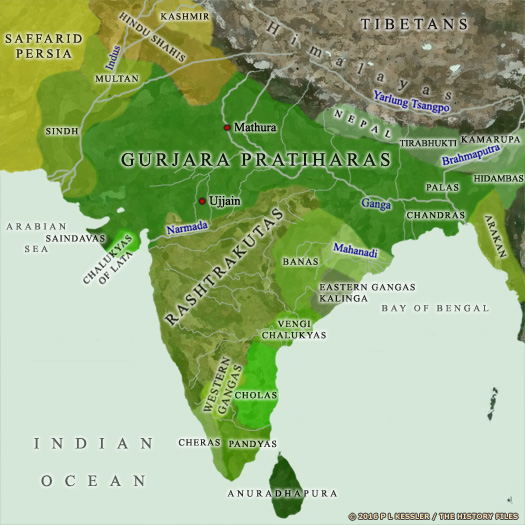

India of AD 900 was remarkably unchanged in terms of its general distribution of the larger states - only the names had changed, although now there was a good deal more fracturing and regional rule by minor states or tribes 962 :

Zabulistan is seized by a rebellious Samanid governor and a semi-independent Afghan kingdom is formed with its capital at Ghazni. Although the rebel, Alptigin, establishes his independent rule of Ghazni, coins from the era show that he nominally acknowledges Samanid overlordship, always a useful ruse for avoiding an attack by former masters.

977 :

Sebuktigin becomes the first Yamanid king of Ghazni when he succeeds to the throne, which is situated south of Transoxiana (and 120 kilometres (eighty miles) to the south-west of Kabul, both in modern Afghanistan). The Ghaznavids govern the region for much of the following two centuries. Then they are ousted by the Ghurids who are themselves displaced by the Khwarazm shahs.

Timurid

Kabul (with Ghazni & Kandahar) :

Following the Shaibanid conquest of Transoxiana in the fifteenth century AD, Southern Khorasan with its centre around Herat was now threatened. Its ruler, Sultan Husayn Bayqarah, did nothing initially, although one of his princes, Babur of Ferghana, attempted to fight back. Finally deciding to mobilise in 1506, Husayn died before he could achieve anything, and the crown was disputed between his sons. Having already realised the hopelessness of the Timurid position there, Babur withdrew southwards to the recently-captured Kabul in 1506 to continue the fight.

Shortly afterwards, he also took Ghazni (near Kandahar), displacing an unpopular Arghunid usurper in the region called Muquim (the Arghunids moved to Sindh and took over there instead). Babur made many attempts to recapture Transoxiana, which he had briefly won before his exile. Each attempt was a failure until he was aided by the Safavid ruler of Persia, Ismail, who subsequently took control of the region himself. The Shaibanids themselves now held much of former Khwarazm, effectively ending Timurid rule of Transoxiana.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Abhijit Rajadhyaksha, from the Encyclopaedia Britannica, from History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century, Henry H Howarth (1880), from A History of Inner Asia, Svat Soucek (2000), from Mannerheim, Stig Axel Fridolf Jägerskiöld, from The Russian Conquest of the Bukharan Emirate: Military and Diplomatic Aspects, A Malikov (Central Asian Survey, Volume 33, Issue 2, 2014), and from External Link: History of Khiva.)

1504 - 1530 :

Babur : Timurid prince from Ferghana in Transoxiana.

1506 - 1507 :

Babur recognises that Khorasan is undefendable and withdraws south. The following year, the Shaibanids invade and capture Herat, putting a final end to Timurid rule. In Transoxiana, the remnants of Khwarazm become an independent Muslim Uzbek state that is later known as the khanate of Khiva, but without Ghazni (modern Kandahar). At Babur's urging, Khorasan is soon recaptured by the Safavid shah of Iran, Ismail. Although only part of it is held permanently, this becomes the Persian province of Khorasan.

Silver coins issued by Kamran Mirza during his reign as an independent king in Afghanistan, bearing his mark stamped over that of Babur's, showing that Babur's old coins had simply been reissued rather than being replaced 1510 - 1511 :

Upon the death of the Shaibanid ruler, Mohammed Shaibani, Babur of Samarkand is able to retake much of his former territory with Safavid Persian help from his base in Kabul. However, he is unable to retain it. The Shaibanids in the form of Sultan Ibars and Sultan Balbars re-conquer the city just eight months later, shortly after capturing Old Urgench, and they assume control of its governance as the khanate of Khwarazm (Khiva).

1519 - 1530 :

From 1519, Babur leads a great many raids on the sultanate of Delhi, which is divided and weakened. In 1526, he is invited by the nobility to invade, and the sultan is killed at the Battle of Panipat. Babur creates a Moghul empire which sacks and controls Delhi as the heart of that empire, while also retaining Kabul within it. In 1530, Kabul and Ghazni are handed by Babur's son to his brother, Kamran, to rule (the mirza attached to his name means 'prince').

1530 - 1545 :

Kamran Mirza : Son. Brother of Moghul Emperor Humayun. A detested ruler.

1540 :

After being present at the rebellion of Hindal in Moghul Agra in 1539, Kamran returns to Kabul and, with the help of his brother, Askari, secures territory as far east as Lahore and proclaims himself king of Afghanistan. Askari : Brother. Governor in Kandahar (1540-1545).

1543 - 1545 :

Kamran's elder brother, Humayun, the exiled Moghul emperor, arrives in Kabul following failed attempts from Amrakot to regain his territory. The two are now implacable enemies, and Humayun is forced to flee to the court of the Safavid shah of Persia. Here he receives enough support to strike out and defeat Askari in Kandahar and then Kamran in Kabul just two years later, also adding Lahore to his domains. Humayun exiles his surviving brothers to Mecca, while Hindal has already died fighting on his behalf.

1545 - 1555 :

Humayun : Brother. Moghul emperor in exile. Regained throne (1555).

1554 - 1555 :

The death of Islam Shah Suri in Delhi leaves his dynasty weak and open to rival claimants, of which their are many. The most powerful of these is the resurgent Humayun, who leads his army eastwards from Kabul in a string of impressive victories. Much of what is now Afghanistan is again part of the restored Moghul empire, with the emperor's relative, Mirza Muhammed Hakim, governing Kabul and the surrounding districts.

Humayun's tomb in New Delhi marks the end point of a remarkable reign which saw him accede and then submit to exile after a decade of opposition, primarily from the Afghan adventurer, Sher Shah Suri, only to reclaim his throne fifteen years later then to die the following year in an accident 1555 - 1585 :

Mirza Muhammed Hakim : Cousin of Moghul emperor, Akbar. Rebelled. Died Jul 1585.

1562 - 1564 :

The Afghan Karrani dynasty captures large tracts of south-eastern Bihar and west Bengal in India. With their assassination of the region's previous ruler, they now seize complete control of Bengal. These Afghans, under the leadership of Taj Khan Karrani, had long been a thorn in the side of regional rulers, previously having conquered parts of modern Uttar Pradesh from Muhammed Shah Adil (Muhammed V of Delhi) before being defeated and pushed out to Bengal.

1566 :

An army from nearby Badakhshan arrives to besiege Kabul. The governor leaves the garrison in place and retreats with his army towards the Indus in the Punjab plain. There, he is incited by Uzbek rebels to besiege Lahore. The Moghul emperor, Akbar, marches to confront him and he retreats back to Kabul, now cleared of its attackers. Akbar chooses not to pursue him.

1576 :

The new Safavid shah of Persia, Esmail, begins to encroach on Afghan territory, putting pressure on Kabul to defend itself. Esmail manages to offended many with his cold and haughty attitude, inherited from his time in prison. One day in 1578 he drops dead unexpectedly. The court doctors suspect poison, but it means that Kabul is temporarily safe.

1581 :

Mirza Muhammed continues to rule Kabul as an independent state, and the governor of Kandahar now also supports him, while he plans to invade Punjab and seize Hindustan. Moghul Emperor Akbar the Great sends his Rajput general, Man Singh of Amer, to attack Kabul, and Man Singh captures the city, while Kandahar is peacefully surrendered by its erstwhile governor. However, Mirza Muhammed is restored as governor of the province.

1585 :

Kabul is formally annexed to the Moghul empire following the death of Mirza Muhammed Hakim. Its future is as a satellite of the Moghuls in Delhi until the Persians renew their interest in the region in the seventeenth century.

1623 :

Taking advantage of a revolt by Shah Jahan, son of the Moghul emperor, the Persians capture Kandahar. The attempt has taken quite some time, with Isfandiyar, son of Khan Arab Muhammad I of Khwarazm, also aiding them in 1621. In return, he is granted five hundred troops to aid him against his rebel brothers in the khanate.

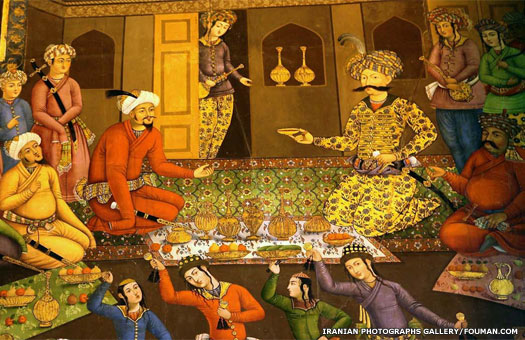

The reign of Shah Abbas was one that involved a restoration of Iranian regional greatness, although he did have to wait eleven years to be able to retake the city of Mashhad where he is pictured in this illustration 1648 :