| KASKANS / GASGA (KASHKU) Occupying a swathe of territory along the south coast of the Black Sea during the second millennium BC Bronze Age, the Kaskans were non-Indo-Europeans. Their language remains unclassified, although it is suspected that it may have been related to the Hattic language of the pre-Hittite city states of Hattusa, Kanesh, Zalpa, and others. Their neighbours to the west were the Indo-European Pala, whom they may have displaced somewhat by their own emergence. To the south were the Hittites, cousins of the Pala, whose empire waxed and waned over the years. The states of Hayasa and Colchis lay to the east.

The Kaskans (Kaška/Kashka, Gasga, or even Gasgas - the same name in different forms) seem to have been in existence as a recognisable people by the seventeenth century BC, according to Hittite records which may have been pushed back in time to extend the Kaskan threat and therefore the scale of contemporary Hittite victories against them. They never formed a unified state - instead they may have moved into territory which had been abandoned by the former inhabitants of Zalpa during the Hittite conquest of central Anatolia. The Kaskans may also have been nudged a little further eastwards to keep the former city of Zapla as their western border by the arrival of Luwian speakers in what became Paphlagonia.

If the Hittite records are to be believed then it is curious that the Kaskan appearance seems to coincide with the collapse of the northern city state of Zalpa. Perhaps the Zalpans, their city now dominated by Hittites, decided to adopt a more guerrilla-based approach to their defence - and it was certainly quite effective at times. Even if the urbanite Zalpans were in fact absorbed into the Hittite population, it is highly likely that their tribal cousins on the periphery of the city provided much of the core of the later Kaskan population. Much of their country was (and still is) rugged and mountainous, with occasional fertile valley regions. During the entire second and first millennia BC its inhabitants were often regarded as ungovernable barbarians.

From the fifteenth century BC onwards, the Kaskans continually threatened the Hittites. It seemed not to matter much whether the Hittites were enjoying a phase of success or were enduring one of their weaker moments - the attacks came nonetheless. Periods of drought were especially risky, as they would force the Kaskans to become bolder. They often attacked and sometimes sacked the Hittite capital at Hattusa during their raids. In return the Hittites portrayed them as aggressive and wild tribesmen and continually campaigned against them. That fighting was far from guaranteed to be a success - the Kaskans could apparently almost match them for combat effectiveness.

The Kaskans were generally pig farmers and linen weavers while they weren't fighting, although that description comes from a possibly-derisive Hittite description. When they were forced to fight by Hittite attacks, they would often rally behind a single leader, seemingly imitating the same practice as that used by the later Celts with their 'high kings'. This would suggest that they formed a loose confederation of Kaskan tribes, perhaps each with its own chieftain, and with each tribe doing its own thing and probably competing against neighbouring tribes until an external threat forced them to unify. The Pala to their west were replaced (or absorbed) by the Phrygians in the late thirteenth century BC, and the Kaskans themselves survived the climate-induced social collapse at the end of the 1200s BC. Unhindered by the now-absent Hittite state, they troubled the north-western borders of the Assyrian empire until the time of Sargon II. Then they simply disappeared from history, probably blending into the emerging populace of Paphlagonia.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from A Geographical and Historical Description of Asia Minor, John Anthony Cramer, and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Britannia, 11th Edition, and Who were the Kaška?, Itamar Singer (The Argonautica and World Culture II, Phasis: Greek and Roman Studies, Vol 10 (II), Rismag Gordeziani (Editor-in-Chief, Tbilisi, 2007, available as a PDF - click or tap on link to download or access it).)

c.1670? BC :

The city state of Zalpa, resurgent after the Hittite victory under Anitta, is finally defeated by Labarna I. It is soon after this, during the reigns of Labarna (whether I or II is unclear) and Hattusili, that the Kaskans appear in the historical record - but only in thirteenth century Hittite records which recount events that may have been stretched backwards in time further than should be the case. These records can be attributed to Muwatalli II, stating that 'Labarna and Hattušili [Hittite kings] did not let them over the River Kumešmaha'. It is more likely that the Kaskans do not appear until the middle of the 1500s BC.

Following their conquest of the Hatti, the Hittites were dominant in central Anatolia between 1650-1595 BC, possibly even being responsible for creating the Kaskans out of marginalised hill dwellers to their north c.1560 BC :

Having

seized the Hittite throne through murder, Hantili I reigns for around

thirty years. Hittite power may have been damaged by this act though,

or is in decline despite it. Thirteenth century Hittite records

which can be attributed to Muwatalli II show that the state loses

territory in the north to the Kaskans: 'The town of Tiliura was

empty from the days of Hantili [presumed to be Hantili I] and my

father Muršili [II] resettled it. And from there they [the

Kaskans] began to commit hostilities and Hantili built an outpost

against them... The [important religious] city of Nerik... was in

ruins from the days of Hantili', ruined by the Kaskans.

c.1430 BC :

The

Kaskans still possess the territory around the ruins of the Hittite

holy city of Nerik, seemingly having seized the area during a period

of Hittite decline over a century previously. Now Tudhaliya II (I)

conducts his third campaign against them, apparently unsuccessfully

as his successor has to offer a prayer to the gods for the city

to be returned. The cities of Kammama and Zalpa are also under Kaskan

control.

c.1400 BC :

The Hittite king, Arnuwanda, has serious problems with the Kaskans, with many northern territories falling into their hands. This includes the cult centre of Nerik (again) which, even when laying aside its religious connections, seems to be a strategic possession for both sides.

The southern coast of the Black Sea is a dramatic and mountainous territory, and it is here in lands that became better known as Paphlagonia that the hard-fighting Kaskans emerged c.1375 BC :

The

Kaskans suffer the loss of their grain to locusts so, in search

of food, they join up with Hayasa-Azzi and Ishuwa, as well as other

Hittite enemies. The devastation to the grain crops may also have

been suffered by others, making it not only easy to get them all

to unite but highly necessary, and the Hittites may be taken by

surprise by the sheer forcefulness of the attack. Recent Hittite

resurgence suffers a knock when their fort of Masat is burned down,

but then the capital, Hattusa, is itself attacked and burned (although

the event is shrouded in mystery). Possibly the secondary capital

at Sapinuwa is also attacked and burned, and the victorious Kaskans

make Nenassa their frontier.

c.1370 BC :

Before

seizing the throne, the Hittite king, Suppiluliuma pushes back the

Kaskan invasion and invades Hayasa-Azzi. Twelve tribes of Kaskans

unite under Piyapili and attempt to support their recent allies,

but are defeated.

fl c.1370 BC :

Piyapili : Temporary leader of twelve tribes.

c.1350 BC :

The reputation of the Kaskans has reached as far south as Egypt. In the Amarna letters, the pharaoh requests that the king of Arzawa sends some of the Kaskan people of whom the pharaoh has heard. For periods around this time, Kaskan relations with the Hittites are sometimes friendly, although the frontier commanders are constantly engaged in hostilities.

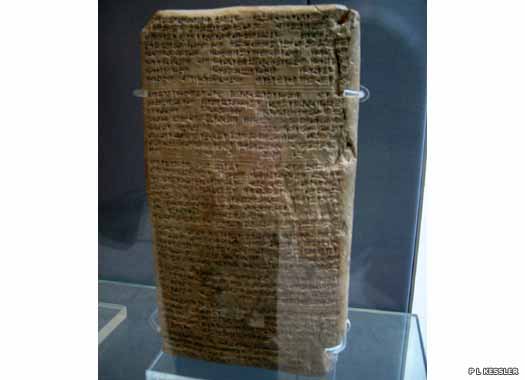

This contemporary cuneiform tablet inscribed with a letter from Tushratta, king of Mitanni, to Pharaoh Amenhotep III, covers various subjects such as the killing of the murderers of the Mitanni king's brother and a fight against the Hittites c.1333 BC :

The old Hittite general Hannutti marches from the Lower Land to attack the Kaskan frontier town of Ishupitta. Unfortunately, the regional plague which has already killed the Hittite's King Suppiluliuma claims his son, Arnuwanda II, and the general too. Kaskan client kings Pazzannas and Nunnutas quickly recover Ishupitta.

fl c.1333 - 1326 BC :

Pazzannas : Hittite client king? Fought off a Hittite attack. Murdered.

fl c.1333 - 1326 BC :

Nunnutas : Hittite client king? Fought off a Hittite attack. Murdered.

c.1326 BC :

The Hittite king, Mursili II, attacks the Kaskans for their rebellion. The Kaskans unite under Pihhuniya - a constant thorn in the Hittite side for many years. In fact, unusually, he seems to be a king rather than the leader of a temporary confederation, and communicates with the Hittites as such. The Kaskans may be heading towards some form of unity until it is interrupted by the Hittites.

The Kaskans advance as far as Zazzissa, but Mursili defeats them and captures the town of Ishupitta and then Pihhuniya behind it. Pazzannas and Nunnutas flee to Arzawa where the king refuses to hand them over. They resurface in the Kaskan lands to lead a fresh rebellion, so Mursili chases them out of Palhuissa into Kammama where the locals put the two fugitives to death.

fl c.1326 BC :

Pihhuniya : Kaskan leader from Tipiya. Captured by Hittites.

c.1310 BC :

Since their great defeat around sixteen years previously, the Kaskans have remained relatively docile clients of the Hittites. Now a new generation of rebellious Kaskan elements takes over the town of Ishupitta before it is re-taken by Mursili II.

The Lion Gates of the Hittite capital were of a style popular throughout the ancient Near East, with an example being found in Mycenae and a later version existing in Jerusalem c.1300 BC :

The Kaskans attack and sack the Hittite capital of Hattusa. Whether this is the reason for the Hittites moving their capital south to Tarhuntassa or a result of it is unclear. The future Hattusili III, in charge of the northern areas of the kingdom, reconquers Hattusa and also the cult centre of Nerik, lost many years before.

c.1200 BC :

The

international system has recently been creaking under the strain

of increasing waves of peasants and the poor leaving the cities

and abandoning crops. Around the end of this century the entire

region is also hit by drought and the loss of surviving crops. Food

supplies dwindle and raids by people who have banded together greatly

increases until, by about 1200 BC, this flood has turned into a

tidal wave. Already decaying from late in the thirteenth century

BC, as Assyria has risen and instability has gripped the Mediterranean

coast, the Hittite empire is now looted and destroyed by various

surrounding peoples, including the Kaskans and the Sea Peoples (and

perhaps even selectively by its own populace).

c.1200 - 750s BC :

The Kaskans do not immediately disappear from the historical record despite the gradual emergence of the Luwian-speaking region of Paphlagonia in the western half of their territory (with the Halizones perhaps being one of the many groups in that region). Neighboured by Tabal to the south and Urartu to the east, they are able to raid south-eastwards to the borders of the Assyrian empire until the eighth century BC when they simply fade out of the historical record.

The Urartuan fortress built into the mountainous hills of Dogubeyazit, close to Mount Ararat in modern Turkey Following this the Armenians soon occupy eastern Anatolia, although the region is often overrun by barbarian peoples such as the Cimmerians. Greeks from the city of Miletus in Caria found the colony of Sinope on the Black Sea coast, probably in the seventh century BC. In the Classical period Pontus is located in the eastern half of the former Kaskan territory.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |