| SAKAS / INDO-SCYTHIANS Incorporating the Amyrgians, Dahae, Haumavarga, Homodotes, Orthocorybantes, Paradraya, Tigraxauda, & Xanthii :

The Indo-Scythian Sakas were nomadic Central Asian tribes which inhabited the region around the River Jaxartes and Lake Issykkul (or Issyk Kul - located in the Tian Shan Mountains in eastern Kyrgyzstan). They seem to have been Indo-European in terms of their ancestry, part of a large group of peoples who had formerly lived around the north shores of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. Migration between the fourth and second millennia BC had sent them far and wide, mostly into Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, but it also later saw them in Iran and India, and even Han dynasty China.

The Sakas eventually found themselves situated to the north and east of the Indo-European Oxus Civilisation of late-third millennium BC Transoxiana, although it is impossible to say whether they were involved at all. They could instead have been part of the Kazakhstan steppe-living 'spiral city' builders who may have traded with the Oxus dwellers but who did not achieve quite the same level of sophistication. Probably related to the Massagetae, their subsequent fate between around 1700-550 BC can only be guessed at. It probably involved a return to a typical Indo-European nomadic existence, which is supported by their adventures with the Yeuh Chi, Achaemenids, and others. They may also have influenced or provided elements of the later Göktürks, who have been linked by some scholars with an Indo-European ancestry.

The Amyrgian subset of Sakas in particular were fairly well attested, after coming into contact with both the Achaemenids (who called them Sakaibish) and the Greeks under Alexander. They were apparently centred on the Amyrgian plain which equates to all of Ferghana and also the Alai valley - well to the east of most of the Sakas. They accompanied Alexander on campaign, under their 'King Omarg' and later entered India along with the Kambojs to found a kingdom in Gandhar (now in northern Pakistan), displacing the ailing Indo-Greek kings.

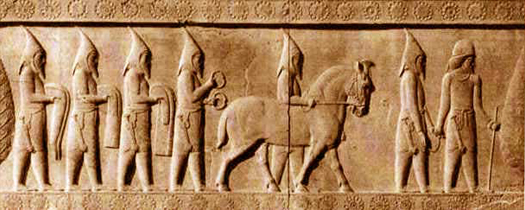

The Tigraxauda name is commonly translated as 'pointed caps' thanks to the headdress worn by members of this group. They appear to have been nearest the Persian border during the eastern campaigns of Darius the Great, fleeing from his advance. Then Darius crossed a river which was probably the Syr Darya - the Jaxartes or River Tanais - after crossing Suguda, and 'smote the Saka exceedingly', slaying their chief. This would be the Haumavarga. The origin of their name is taken to mean that they practiced haoma-drinking. Haoma - the soma of Rigved - is a medicinal and health-giving extract from plants which is associated with ancient Zoroastrian healing practices. The shift between soma and haoma is another example of the 's' to 'sh' to 's' shift that can be seen between Indo-Aryans and Indo-Iranians. More than just medicinal, haoma appears to have been psychotropic in nature if the Rigved is read correctly. The third of the early Saka 'nations' was that of the Paradraya. This name breaks down into 'para' and 'draya', the first part meaning 'across' and the latter almost certainly being 'darya' or 'river'. When Darius boasted of the limits of his empire he gave as the north-eastern corner the 'Sakaibish tyaiy para Sugdam' - the Sakas across/beyond Suguda, on the other side of the Syr Darya, which forms the boundary between Suguda and Scythia.

Later groups were noted in the fifth century by Xerxes and others. The region known as Daha was added to the empire, the name coming from 'daai' or 'daae', meaning 'men', perhaps in the sense of brigands. Daha or Dahae would appear to be the region on the eastern flank of the Caspian Sea, bordered by the Tigraxauda to the north. This contained a confederation of three tribes, the Parni, the Pissuri, and the Xanthii. With the latter, the 'x' in Xanthii has a 'ks' sound which is interchangeable with 'sk' in place of the 'x', possibly providing 'skanth' which can also be seen in the region name 'Skudra'. It turns out that the Xanthii may have been a branch of the Sakas and Scythians.

In the 320s BC, the Amyrgian plain saw the Saka Haumavarga neighbouring the Saka Tigraxauda. Guive Mirfendereski at the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies equates the Massagetae with the Haumavarga (but not the Tigraxauda?), suggesting that Herodotus had produced 'Massagetae' as his own Greek pronunciation of Haumavarga and Amyrgian to describe a specific group of Haumavarga, while the Tigraxauda seem to have become the Orthocorybantes.

In the 280s BC, the Greek explorer and satrap, Demodamas, undertook military expeditions across the Syr Darya to explore the lands of the Sakas, repopulating Alexandria Eschate (modern Khojend) in the process following its earlier destruction by barbarians. From his material, and that recorded by Megasthenes around a generation before, another group of Sakas could be perceived at this time, known as the Homodotes (Pliny's Homodoti, which is based originally on Demodamas, and who are one of a list of regionally neighbouring tribes called the Astacae, Rumnici, and Pestici). The Homodotes were located in the (northern) Emod and at the headwaters of the Oxus (the Amu Darya).

(Information by Peter Kessler and Abhijit Rajadhyaksha, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from Ancient India, R C Majumdar (Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Ltd, 1987), from Studies in Indian History, L Prasad (Cosmos Bookhive, Gurgaon, 2000), from the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies in a theory proposed by Guive Mirfendereski, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, from Indian Numismatic Studies, K D Bajpai, from A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India, P N Chopra & B N Puri, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, René Grousset (1970), from Persica, Ctesias of Cnidus (original work lost but a section is repeated by Photius in ninth century AD Constantinople), and from External Links: Indo-European Chronology - Countries and Peoples, and Indo-European Etymological Dictionary, J Pokorny, and The Ethnic [Background] of [the] Sakas (Scythians), I P'iankov, presented by the Iran Chamber Society, and the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Zoroastrian Heritage, K E Eduljee, and Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps).)

653 BC :

The Cimmerian king, Tugdamme, begins to threaten the borders of the powerful Assyrian empire during the reign of Ashurbanipal. Assyrian inscriptions record him as being 'King of the Saka and Qutium'. This is very telling, because it suggests that he rules not only over his own Cimmerian people (which is so obvious that it need not be mentioned), but also the Scythians (identifying them as 'Saka', a form of the name that very soon becomes prominent amongst Scythian groups to the east of the Caspian Sea, in Transoxiana).

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) c.546 - 540 BC : The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea). Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhar, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse.

Cyrus the Great attacks the Sakas and takes prisoner their king, Amorges. His wife, Sparethra, collects together an army of 300,000 men and 200,000 women and attacks the forces of Cyrus, defeating them according to Ctesias. Important Saka prisoners are exchanged for Amorges and the two sides agree terms of friendship.

fl 530 BC :

Amorges / Homarges : Saka chief. Served with Persian King Cyrus the Great.

530 BC :

The end of the reign of Cyrus the Great reign is spent in military activity in Central Asia where, according to Herodotus, he dies in battle in 530 BC. Intent on taming the Massagetae, he advances across the River Axartes which is not only broad but which contains many large islands. Ctesias relates that he is aided by Saka chief Amorges, although Ctesias is highly unreliable as a chronicler.

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gadara and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka.

516 - 515 BC : A subsequent cuneiform inscription set up by Darius lists the nations that comprise the Persian empire - the Behistun inscription. It includes three nations using 'Saka' as a prefix to their names: Saka Haumavarga, Saka Tigrakhauda, and Saka Paradraya. The Saka Tigrakhauda (commonly translated as 'pointed caps' thanks to their headdress) appear to be the nearest, and they flee from Darius' advance. Then Darius crosses a river (probably the Syr Darya - the Jaxartes - after crossing Suguda), and 'smote the Saka exceedingly', slaying their chief. This would be the Saka Haumavarga. The origin of their name is taken to mean that they practice haoma-drinking. Haoma is a medicinal and health-giving extract from plants which is associated with ancient Zoroastrian healing practices.

Saka Tikrakhauda (otherwise known as 'Scythians' who in this case can be more precisely identified as Sakas) depicted on a frieze at Persepolis in Achaemenid Persia, which would have been the greatest military power in the region at this time ? - 515 BC :

Skunkha : Saka Haumavarga chief. Executed by Darius.

515 - ? BC :

? : Unnamed Saka Haumavarga vassal chief.

515 BC :

The third Saka 'nation' is that of the Saka Paradraya. This name breaks down into 'para' and 'draya', the first part meaning 'across' and the latter almost certainly being 'darya' or 'river'. When Darius boasts of the limits of his empire he gives as the north-eastern corner the 'Sakaibish tyaiy para Sugdam' - the Sakas across/beyond Sugdam (Suguda), on the other side of the River Tanais (otherwise known as the Jaxartes/Iaxartes or Syr Darya, which forms the boundary between Suguda and Scythia).

The Saka Tigrakhauda occupy open grasslands around the Aral Sea, in modern south-western Kazakhstan. Their aforementioned pointed caps would be sized according to seniority, with the tallest being reserved for the chieftain. It is this group of Sakas that is most likely to be the Massagetae of Strabo. Strabo also identifies the Attasii and the Chorasmii of the region of Chorasmia as Massagetae, making them a sub-group of the main Massagetae collective, otherwise known to the Achaemenids as Saka Tigrakhauda.

479 - 465 BC :

Xerxes apparently adds two new regions to the Persian empire during his reign, neither of which are very descriptive or clear in their location. The first is Daha, from 'daai' or 'daae', meaning 'men', perhaps in the sense of brigands. Daha or Dahae would appear to be the region on the eastern flank of the Caspian Sea, bordered by the Saka Tigraxauda to the north, and the satrapies of Mergu, Uwarazmiy, and Verkâna to the north-east, south-east, and south respectively. It contains a confederation of three tribes, the Parni, the Pissuri, and the Xanthii. With the latter, the 'x' in Xanthii has a 'ks' sound which is interchangeable with 'sk' in place of the 'x', possibly providing 'skanth'. The Xanthii may be a branch of the Sakas and Scythians.

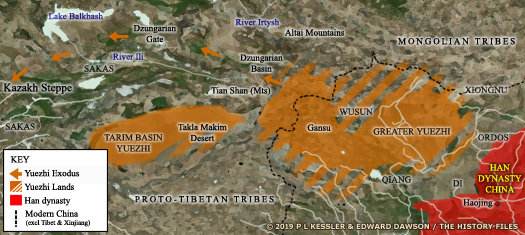

This map shows the Scythian lands at their greatest extent, primarily before they came to the notice of Classical authors c.320s BC : Two centuries later, the Sakas appear to reside midway between modern Iran and India, or at least the Amyrgian group or tribe does. Achaemenid records identify two main divisions of 'Sakas' (an altered form of 'Scythians'), these being the Saka Haumavarga and Saka Tigraxauda, with the latter inhabiting territory between Hyrcania and Chorasmia in modern Turkmenistan (pretty close to their territory in 515 BC).

The Amyrgian plain which forms the centre of their territory had previously been part of, or close to, the lands of the Indo-European Massagetae, with the Saka Haumavarga neighbouring the Massagetae (and the Saka Tigraxauda). Again this has led some scholars both modern and ancient to link the two together as the same people. Guive Mirfendereski at the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies also equates the Massagetae with the Saka Haumavarga (but not the Tigraxauda?), suggesting that Herodotus had produced 'Massagetae' as his own Greek pronunciation of Saka Haumavarga and Amyrgian to describe a specific group of Haumavarga, while the Saka Tigraxauda become the Orthocorybantes.

The Amyrgian group of Sakas has already served in the army of Xerxes of Persia in the fifth century BC (mentioned by Herodotus, thanks to whom 'Amyrgian' may mean 'eastern' Sakas). Their name is either a reflection of the Amyrgian plain that they occupy, or they have given their name to the plain as the 'eastern Sakas', and it does seem likely that they are the very same group as the Saka Haumavarga, but with a Greek interpretation of their name instead of a Persian one. Phonetically, the two versions are very close.

The appearance of ferocious mounted Scythian warriors on the Pontic steppe must have instilled a sense of worry and fear in many local groups (although armour such as that pictured here certainly did not appear so early), while above is a map showing the Scythian lands at their greatest extent The late Achaemenid Persians and the Greeks under Alexander place the Amyrgian Sakas beyond Sogdiana, across the River Tanais (Syr Darya). This is thanks to their having encountered the Sakas after crossing Sogdiana and the Syr Darya in the approximate region of Alexandria Eschate ('the furthest', modern Khojend) - and it puts them precisely where the Saka Paradraya had been in 515 BC. It is generally accepted that they control all of Ferghana (immediately to the east of Transoxiana) and the Alai valley. Indeed, they may have been relocated onto the plain following their conquest by the Persians.

Chares of Mytilene travels with the Greek army of Alexander the Great, chronicling the journey with reliable geography. He places the headquarters of 'King Omarg' at some 800 stadia (150km) from the crossing at the Tanais, thereby not limiting them to the right bank of the Tanais.

c.320s BC :

'Omarg' / 'Amorg' : Amyrgian Saka. Served with Greek general Alexander the Gt.

290s/280s BC :

A former general under Seleucid rulers Seleucus I Nicator and Antiochus I Soter, Demodamas later serves twice as satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana. During this time he undertakes military expeditions across the Syr Darya to explore the lands of the Sakas, repopulating Alexandria Eschate (modern Khojend) in the process following its earlier destruction by barbarians.

The accounts of these expeditions are recorded by Demodamas (which later form source material via other writers for Roman authors). From his material, and that recorded by Megasthenes around a generation before, it can be deduced that yet another group of Sakas are called the Homodotes (Pliny's Homodoti, which is based originally on Demodamas, and who are one of a list of regionally neighbouring tribes called the Astacae, Rumnici, and Pestici). The Homodotes are located in the Emod and at the headwaters of the Oxus (the Amu Darya). The Mount Emod here is not the well-attested one that separates India in the north from 'Scythia inhabited by the Scythians known as Sakas' (Megasthenes). Instead, Megasthenes appears to have confused or combined two different Emods, the other being close to the headwaters of the Oxus.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi c.165 - 160 BC :

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement. By about 160 BC the Greater Yuezhi have encountered the outlying Saka groups on the eastern Kazakh Steppe, primarily in the Ili river valley immediately to the south of Lake Balqash, which they now occupy. Seemingly, these Saka groups are easily dominated by the Greater Yuezhi, probably due to the sheer weight of numbers on the latter side, while the Saka are at the eastern edge of their vast swathe of territories which stretch all the way back to the shoreline of the Caspian Sea.

fl c.150s BC :

? : Unnamed Amyrgian Saka. Expelled from Ferghana.

c.155 BC :

The Sakas (in the form of the Amyrgian branch) are displaced from Ferghana by the Greater Yuezhi. They are undoubtedly pushed towards neighbouring Sogdiana, where they are dominant enough to take control of the region, displacing whichever regional tyrants may have arisen or becoming their overlords. This is an event that is connected with the migration of the Greater Yuezhi across Da Yuan (the Chinese term for Ferghana), following another defeat, this time by an alliance of the Wusun and the Xiongnu. The Greater Yuezhi are forced to move again, causing other tribes also to be bumped out of position.

The Altai Mountains link together the borders of Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Russia, and Xinjiang, providing the source for the rivers Irtysh and Ob and also, it would seem, the source region for the early Turkic tribes These mass migrations of the second century BC are confused and somewhat lacking in Greek and Chinese sources because the territory concerned is beyond any detailed understanding of theirs. Whatever the reason, the Saka king transfers his headquarters to the south, across the Hanging Passage that leads to Jibin. This is part of a southwards trend for the Sakas, and by approximately the mid-first century BC, Saka kings appear in India.

Greco-Roman writer Ptolemy later records the [Sakas of the] Kaspirs (meaning Jibin) as occupying a vast territory from the River Bidaspes (Jhelum, in Punjab) to the mountain of Quindion (Vindhya), and including in this the town of Modura (Mathura). This evidently reflects the situation during the early period of Saka dominion in India when Kashmir is still regarded as the centre of the kingdom.

c.140 - 130 BC :

Elements of the Sakas have long been pressing against Bactria's borders. Now, following a long migration from the borders of the Chinese kingdoms, the Greater Yuezhi start to invade Bactria from Sogdiana to the north. Initially, Sakas who are already in Bactria become vassals to the Greater Yuezhi but, within a decade, the Greater Yuezhi manage to force the collapse of Bactria. They occupy its territory on a permanent basis and the Sakas are largely forced southwards, although they also spend this period trying to force a way westwards into Parthian territory.

The landscape around the walls of the ancient city of Bactra, capital of Bactria (shown here - now known as Balkh in northern Afghanistan, close to the border along the Amu Darya), was and still is very diverse, offering both challenges and rewards to any settlers there, including the newly arrived Sakas, while above that is a map showing the estimated migratory route of the Greater Yuezhi in the second century BC c.138 - 124 BC :

In the core Parthian homeland, King Phraates comes into conflict with western elements of the Sakas. The Parthians are defeated in several battles, one of which ends with the death of Phraates himself around 126 BC. The Sakas (partially displaced by the Greater Yuezhi) continue to press Parthian borders for territory, subsequently killing King Artabanus. They may occupy areas of Parthian territory for a time, relieving the Greater Yuezhi pressure on them.

The modern writer, René Grousset, instead attributes the death of Artabanus II to the Greater Yuezhi who are now settled in Bactria. The answer could lie in the fact that Saka groups have been dominated by the Greater Yuezhi since the latter's arrival thirty or forty years beforehand, so the Greater Yuezhi could be the driving force behind the fighting against the Parthians while a Saka could still be responsible for the wound which kills Artabanus II.

115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and around Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhar. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies.

c.90 - 80 BC :

The Greater Yuezhi continue to drive the Sakas southwards from Central Asia, forcing them further into Indo-Greek territory. One Maues of the Sakas takes control around Gandhar, creating a capital at Taxila in Punjab (formerly in northern Indus, now in northern Pakistan). Gandhar falls within a region stretching into Parthian lands which remains known as Sakastan or Sistan even today. Taxila is also in today's Pakistan. Maues is known in Chinese records as Yinmofu of Jibin, suggesting that the Sakas have been driven from there during the leadership of Maues and that therefore he is already king well before the arrival of the Sakas in Gandhar.

c.90 - 60 BC :

Maues / Moga / Yinmofu : 'Great king of kings'. Scythian general or Indo-Greek?

c.80 BC : There is the possibility that Maues is a hired Scythian general who wishes to absorb Greek culture rather than conquer it, as evidenced by his coins (while the coins show his name as Maues, epigraphic evidence provides 'Moga' which is very similar to the Omarg or Amorg of the 320s BC and would seem more to be a title, given how similar it is to 'Amyrgian').

A Hermaeus coin from Gandhar at the beginning of the first century AD, which type was copied far and wide, especially by Sakas, Greater Yuezhi, and Kushans - could Hermaeus be the same man as Maues of the Sakas? He issues some coins jointly with a Queen Machene, who may be an Indo-Greek ruler. The Indo-Greek king, Artemidoros (c.90-85 BC), describes himself as 'son of Maues'. Curiously, the contemporary of Artemidoros in Indo-Greek Paropamisadae (western Indo-Greek territory) is Hermaeus Soter. The name is surprisingly close to that of Maues, and Hermaeus holds a level of importance with nomad rulers during and after his reign, with his coins being copied far and wide, especially by the Greater Yuezhi, Sakas, and Kushans.

c.75 - 65 BC :

Vonones : (Not to be confused with the Parthian Vonones.)

c.75 - 65 BC :

Spalahores : Brother, satrap, and successor to the throne around 65 BC.

c.75 BC :

Following the death of Maues, the Indo-Greeks regain control of Paropamisadae (under Artemidoros) and northern Indus (Punjab) under Apollodotus II. Vonones is confined to the north-west of India. However, the Indo-Greeks progressively lose ground to the Sakas, Greater Yuezhi, and Parthians in the west.

c.72 BC :

The Sakas appear to capture Modura around this time (Mathura in Utter Pradesh, northern India). Benefiting from their earlier interaction with the Greeks, they have been employing the Greek system of rule and appointing kshatraps (satraps, or governors) to manage each region, with one being placed in charge of Mathura. The Taxila 'Copper-Plate Inscription of Patika, the year 78' records a brief event during the office of Liaka Kusuluka, possibly the very first Western Satrap of Mathura. His son, Patika, establishes a new relic of the Lord Sakyamuni, and a sangharama through Rohinimitra, overseer of the work in this sangharama, 'for the worship of all Buddhas'.

c.70 BC :

The Sakas expel the Indo-Greeks from Arachosia but subsequently lose it to the Parthians. Parthian rule seems to be limited and perhaps doesn't include the entire region. By now, Saka rule covers a vast area of what is now southern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-west India, and the term Indo-Scythian can truly be applied to the Sakas from this approximate point onwards. The Saka satraps of the north and east still enter the historical record through their coins and interaction with surrounding powers, but Western Satraps live a much more obscure life in the Saka Indian territories.

c.65 - 60? BC :

Spalahores : Former satrap (c.75-65 BC).

c.60 - 57 BC :

Spalirises : Brother (or the same person), and definite brother of Vonones.

c.57 - 35 BC :

Azes I : Neighbouring (rival?) king who consolidated Saka territory.

c.57 BC : Azes consolidates Saka territory by absorbing that of Spalirises into his own, presumably when the death of the latter king leaves his territory unguarded. However, in the same year the Indo-Scythians are repelled from the area of Ujjain (Ozene) by King Vikramaditya of Malwa after occupying it for perhaps two decades or more. To commemorate the event Vikramaditya establishes the Vikrama era, a specific Indian calendar that uses 57 BC as its starting date.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahans of India To the north and east of Azes' now enlargened territory, King Hippostratus is one of the most successful late Indo-Greek kings, until he loses to Azes in a battle which probably takes place at the River Jhelum. Azes establishes his own dynasty in western Indus (Punjab). An alliance between Azes and the Indo-Greeks may be agreed after this, as the latter continue to rule eastern Indus (Punjab).

c.57 - 35 BC :

Azilises : Ruled in Gandhar as a joint king with Azes.

fl c.50 BC :

Spalagadames : Son of Spalahores, and a satrap.

c.50 BC? :

The Kushans capture the territory of the Sakas in what is now Afghanistan but which at this time includes the former region of Arachosia and neighbouring territories. They probably also cause the downfall of Indo-Greek king Hermaeus, as they conquer Paropamisadae in the process. The Sakas consolidate their rule in northern India as compensation for the loss of Gandhar. They also fight the Satvahanas in India, and later enter into matrimonial alliances with them.

Mathura has quickly become an important Saka holding, with its kshatraps issuing their own coins. A series of kshatraps are known for a period that could stretch anywhere between 70 BC and the mid-first century AD. No two numismatic experts seem to agree on dating. It is also possible that they should not be grouped together in a single block. The first two, Hagamash and Hagan, are usually placed before Kharahostes and Rajuval, so they remain here. The later ones bear Indian names, showing a degree of integration with the locals and suggesting that they at least should be given dates in the first century AD, after the Rajuvul-Sodasa.

This photo illustrates a Kushan coin of Kadphises I which was discovered in the Bactria-Tokharistan region and which has on it a corrupt Greek legend c.50s-10s BC? :

Hagamash : Kshatrap (satrap) in Mathura. Dates very uncertain here.

c.50s-10s BC? :

Hagan : Elder brother? Kshatrap in Mathura.

c.35 - 12 BC :

Azes II : Possibly the same person as Azes I, thanks to a coin overstrike.

fl c.35 BC? :

Bhadayasa : Kshatrap (satrap) in Eastern Punjab. Dated by coins alone.

Mamvadi : Kshatrap (satrap - coin evidence). Dating entirely unknown.

c.10 BC :

The death of Azes II coincides with the rise of the Kushans in the west, but they remain rulers throughout the north-west frontier and in northern Indus (Punjab), Sindh, Kashmir, western Uttar Pradesh, Saurashtra, Kathiawar, Rajputana, Malwa (although not again in Ujjain (Ozene) until AD 78), and the North Konkan belt of Maharashtra.

Following the reign of Azes, the Sakas appear to fragment to an extent, with no overall ruler (mahakshatrap). Instead, local satraps (kshatraps) probably hold a level of independence and continually vie for supremacy, with control of Taxila being the ultimate prize. Three main satrapies are prominent now, with that of Kashmir shown in red and Mathura shown in green (the latter satraps are sometimes termed 'northern satraps' to differentiate them from the third group, the Western Satraps in Gujarat and Malwa). Other, more minor satraps are shown in light grey, while those kshatraps who became dominant over their peers often adopt the title Mahakshatrap.

fl c.10s BC? :

Granavhryaka : Kshatrap in Kapis? Dates estimated based on his son's.

after 10 BC? :

Arsakes Dikaios : Kshatrap. Dated post-Azes II by coinage. District unknown.

c.10 BC - AD 10 :

Zeionises / Jihonika : Son of 'Manigula'. Kshatrap in Kashmir & Chuksa.

Zeionises is kshatrap of Kashmir, which title seems to be passed onto Kharahostes before being lost to the Indo-Parthians. He is also claimed as satrap of Chuksa (which would make him one of the Western Satraps) thanks to a silver jug that is later discovered at Taxila, and 'son of Manigula, brother of the great king'. The great king in question is unknown, but Azes would be the most likely candidate.

c.AD 10 :

In the north, Rajuvul succeeds Hagamash and Hagan as kshatrap of Mathura. It is only during Rajuvul's time that the office becomes much more powerful, with the absence of Saka central authority. His chief wife is reputedly Aiyasi Kambojak, who is also referred to as Kambojik, and who is a member of the Kambojs tribe. Verses of the Mahabharat are believed to be composed around this period, and they include the Kambojs.

It is now that the Indo-Greek kingdom disappears under Indo-Scythian pressure. It seems to be Rajuvula (see above) who invades what is virtually the last free Indo-Greek territory in the eastern Punjab, and kills Strato II and his son. Pockets of Greek population probably remain for some centuries under the subsequent rule of the Kushans and Indo-Parthians. Rajuvula's predecessor, Kharahostes, has inherited Kashmir from Zeionises, but this prized possession is almost instantly lost to the Indo-Parthians. Subsequent northern and eastern Saka rulers are known largely through numismatic evidence and inscriptions, notably the Mathura lion capital.

Carved from sandstone, the Mathura lion capital was raised by the Sakas in first century AD Mathura, and carries Pakrit inscriptions that mention several of the 'northern satraps' of this region AD 15 - 45 :

Aspavarma : Apracaraja dynasty kshatrapa in Bajaur.

fl c.AD 20? :

Higaraka : Kshatrap of Chhahar& Chuksa. Numismatic evidence.

fl c.20 :

Itravasu : Apracaraja dynasty kshatrapa in Bajaur.

fl c.30? :

Abhirak / Aubhirakes : Kshatrap of Chhahar& Chuksa. Numismatic evidence.

c.30-80 :

During his reign, Kushan Emperor Kadphises I subdues the Sakas and establishes his kingdom in Bactria and the valley of the River Oxus (the Amu Darya), defeating the Indo-Parthians. Then he captures Gandhar. Kadphises may be a descendant of the Kushan leader Heraios, or perhaps even the same person, and is apparently confused by some with one of the later Indo-Greek kings, Hermaeus Soter, but he also shares his name with some of the later minor Indo-Scythian rulers, suggesting a possible family connection there. The Sakas are eclipsed.

fl c.60 :

Bhumak : Son. Kshatrap. Confirmed by numismatic evidence.

79? - 124 :

Nahapan / Nambanus : Son. Under nominal Kushan suzerainty until 119.

c.80s? :

The Sakas have been eclipsed, although it is apparent that they retain at least one of their former offices, in Mathura (see above). This seems to be under the suzerainty of the Indo-Parthian king, Gondophares, for at least the early part of Kshatrapa Sodasa's 'reign' (the office is at least partially inherited by this time rather than being an appointment). But Sodasa is also claimed as being a contemporary of 'Kshaharat' (for kshatrap) Nahapan, which must give Sodasa a long reign between about AD 50 and AD 80 or even later. It is Nahapana at this time who signals the gradual resurgence of Saka power by capturing the important prize of Ujjain (Ozene) in the sixth year of his reign.

119 :

Nahapan shrugs off weakening Kushan supremacy and achieves the virtual independence of the western satraps. He goes on to occupy large swathes of Satvahan territory in western and central India and creates a new Saka centre of power far to the south of the original lands.

Naganika, the wife of Shathakarni, ruler of the Satvahanas, commissioned the cave inscriptions in the Naneghat, or 'coin pass', an important toll for travellers passing though this Western Ghats trade route 124 :

Nahapana is defeated by the resurgent Satvahan king, Gautamiputra Satkarni. As a result the Sakas lose Malwa and western Maharashtra and are forced to concentrate on Gujarat. He is apparently succeeded by Chastana, who is mentioned by Greco-Roman writer Ptolemy as 'Tiasthenes' or 'Testenes', and who rules a large area of western India, especially the area of Ujjain (Ozene), during the reign of the Satvahan king, Vasisthiputra Sri Pulamavi.

Saka (Western) kshatraps (Kardamaka Dynasty) :

Chastana or Castana was the founder of a fresh dynasty due to the fact that his father was Ghsamotika rather than his predecessor, Nahapana. This kshatrap is better known by Greek authors as Tiasthenes or Testenes. Both of the latter are much closer to an Indo-Greek version of his name and suggests that he actually did bear a Greek or Greek-inspired name rather than an Indian one. Chastana's father is given as Ghsamotika, Ysaneotika, and even Zamotika - all the same name rendered in different forms by different writers.

Despite the location of Ujjain ('Ozene') deep within India, the Sakas had clearly not yet become entirely naturalised. They also seem not to have become entirely independent, still apparently paying homage to the Indo-Parthian and then Kushan rulers to the north. Usefully, Chastana's reign can be firmly fixed around AD 130 by the Andhau (Cutch) inscription, providing an anchor for the somewhat vague dating of other rulers of this period.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Abhijit Rajadhyaksha, with additional information by Manjiri Bhalerao, from A Sourcebook of Indian Civilization, Niharranjan Ray, from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, and from Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen.)

fl c.130 :

Chastana / Tiasthenes / Testenes : Son of Ghsamotik. Kshatrap of Ujjain (Ozene).

fl c.130 :

Jayadaman : Son and co-ruler. May have predeceased his father.

c.130 - c.170 :

Rudradaman I : Son. Initially a co-ruler with his grandfather. Mahakshatrap.

Maintaining the capital at Ujjain, Rudradaman I enjoys a long reign and successfully wages various wars against the Satvahans. He is also the father-in-law of the Satvahan king, Vashishtaputra Satkarni, whom he defeats twice in battle, leading to the decline of the Satvahanas. His kingdom extends over Malwa, Rajputana, Gujarat, and Maharashtra (except Pune and Nasik).

Typical Indo-Scythians in India, still the notable horse-borne warriors of their Indo-European heritage but by now greatly imbued with Indian cultural influences By this period, if not before, the last Indo-Parthians are conquered by the Kushans while Mathura is still under the control of the Kushans and governed by Saka satraps. Indo-Parthians also remain in some of the areas that they have conquered in the past. After consolidating his newly-created empire, and having converted to Hinduism, Rudradaman divides it into provinces so that it is easier to administer. The Girnar records show that an Indo-Parthian amatya (governor) by the name of Suvisakha is placed in charge of the administration of Ananta-Surastra. One Kuplaipa is made viceroy of Gujarat, 'Mahadandanayaka' (actually a title meaning 'great general') becomes governor of Malwa, and Rupiamaa is kshatrapa of Bhandara, the easternmost extension of Saka power.

fl c.150 :

Rupiamaa : Kshatrap in Bhandar based on pillar inscriptions.

c.170 - 175 :

Damajadasri / Damaghsada I : Son of Rudradaman. Mahakshatrap. Damajadasri's reign is recorded as seeing a decline in the power of the western kshatraps following conquest by the Satvahans. The rise of the Malavas in the north also threatens them. With his son's accession, dates start to be added to coins, making it easier to construct a coherent list during this increasingly troubled time.

fl c.181 :

Rudrasimha I : Brother. Kshatrap.

175 :

Jivadaman : Son of Damajadasri. Deposed by Rudrasimha. Died AD 199.

175 - 188 :

Rudrasimha I : Uncle, and former kshatrapa (c.170). Deposed. Died AD 197.

188 - 191 :

Isvaradatt : Usurper, but also claimed as such for AD 242.

191 - 197 :

Isvaradatta's place here as a usurper is uncertain, but if correct then he is responsible for deposing the previous usurper, Rudrasimha I. In turn, he is removed by a resurgent Rudrasimha who soon dies in office to be succeeded by the original deposee and rightful ruler, Jivadaman.

Rajasthan's famous Thar Desert, which is also referred to as the Great Indian Desert, today forms part of the India-Pakistan border, lying essentially between Bikaner and Jodhpur 191 - 197 :

Rudrasimha I : Restored. Died.

197 - 199 :

Jivadaman : Restored upon the death of his uncle. Died without heir.

200 - 222 :

Rudrasena I : Cousin.

early-3rd century :

By the middle of the century the Satavahan kingdom has fragmented into many parts, each having a ruler of its own who claims to be the true Satvahan descendant. Their perennial enemy, the Sakas, assume overlordship of Goa, and already control Malwa, Gujarat, Kathiawar, and parts of western Rajputana, but have lost North Konkan to the Satvahans (probably during the reign of Damajadasri).

222 - 223 :

Samghadaman : Brother.

224 :

Having been all but independent for some time, Margiana is currently ruled by one Ardashir who is to be differentiated from Ardashir I of the Sassanids. Following the Sassanid victory over the Parthians at the Battle of Hormozdgān, the Sassanids have become the great power in Persian lands. Ardashir of Margiana now submits to Ardashir I. Margiana is permitted to continue minting its own coinage for now, while the Sassanids are still consolidating their power.

223 - 232 :

Damasen : Brother.

c.230 - 250 :

The Kushans are toppled in Bactria and Arachosia and are forced to accept Sassanid suzerainty, being replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the Kushanshahs or Indo-Sassanids. There is a split in Kushan rule, so that a separate, eastern section rules independent of the Sassanids, while some of the nobility remain in the west as Sassanid vassals. Even so, Kushan power still gradually wanes in India. If the western kshatraps have remained under Kushan domination to this point then they are almost certainly released from it now.

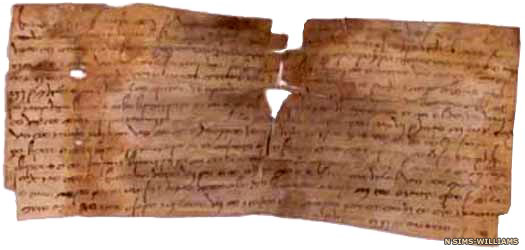

A Kushanshah letter addressed to their mid-fourth century AD ruler, Varhran, from the daughter of a princess named Dukht-anosh, a Middle Persian name 232 - 239 :

Damajadasri II : Son of Rudrasen I.

234 - 238 :

Viradaman : Son of Damasen. Joint ruler or kshatrap?

239 :

Yasodaman I : Brother.

239 - 250 :

Vijaysen : Brother. Lost the throne temporarily?

242 :

Vijayasena apparently finds his throne usurped in this year. Isvaradatta is mentioned in connection with this but he is a usurper of 188-191, and if he has survived this long it seems unlikely that he would be able to commit the very same act again. Whomever the usurper is this time around, it takes Vijaysen around eighteen months to regain his throne.

251 - 255 :

Damajadasri III : Brother.

255 - 277 :

Rudrasena II : Nephew, and son of Viradaman.

277 - 282 :

Visvasimha : Son.

278 - 282 :

Bhratadarman / Bhartrdaman : Brother. Kshatrap under Visvasimha.

282 - 295 :

Bhratadarman / Bhartrdaman : Former kshatrapa, now mahakshatrapa.

293 - 304 :

Visvasen / Vishwasen : Brother. Joint ruler (293-295)? Killed without heir?

296 :

In the west the Sassanids regain Harran and make it a permanent possession. Around this time they seemingly 'overthrow' the Sakas too, although this seems to be more of a check of Saka power which is already beginning to fade.

Saka (Western) kshatraps (Rudrasimha Dynasty) :

The rise of Rudrasimha III meant a new dynasty for the western kshatraps. The fate of his predecessor, Visvasen, seems to be unknown. Did he die without producing an heir, or was he killed and his throne usurped? The replacement dynasty as such seems to be unnamed in records, so Rudrasimha's name is used here, but Rudrasimha himself may not have been of kingly status. His father is named as Swarmi Jivadaman - a swarmi or svari being a mere lord (perhaps a distant relative of the ruling family) - and his accession seems to have begun immediately following the end of Visvasena's reign - his coinage suggesting that he was not a kshatrapa beforehand.

Some modern sources give a starting date of 226 for Rudrasimha II, but this is clearly incorrect as a proper date as his short-lived dynasty fell foul of Chandragupt II, who only became king himself in AD 375. Instead it refers to a specific Indian-based dating era for the Sakas themselves which should be shown with equivalent anno domini dates. The dynasty may have amounted to a restoration of Saka power following the fall or eclipse of the previous rulers. By this time Saka power was beginning to fade and not much is known of their rulers except through numismatic evidence. Having been damaged by the Sassanids in the late third century AD, their distant provinces now began to drift away from their control. A brief revival was engineered under Rudrasimha II, but it proved transitory. The Guptas soon put an end to their rule entirely.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Abhijit Rajadhyaksha, with additional information by Manjiri Bhalerao, from A Sourcebook of Indian Civilization, Niharranjan Ray, from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, from Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen, and from Literary and Historical Studies in Indology, Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi.)

304 - 348 :

Rudrasimha II : Son of Lord (Svami) Jivadaman. Kshatrap.

317 - 332 :

Yasodaman II : Son. Joint ruler? Predeceased his father?

332 - 348 :

Rudradaman II : Son? Joint ruler?

348 - 380 :

Rudrasen III : Brother of Rudrasimha II. Killed by Gupta Chandragupt II.

380 :

Following the reign of Samudragupt of the Guptas, there is the possibility that his eldest son, Ramgupt, succeeds him. While his very existence is sometimes doubted, it seems to be Ramgupt who embarks on an ill-planned campaign against the Sakas in Gujarat and is trapped along with his army, only to be rescued by his brother, the future Gupta king, Chandragupta II.

Two sides of a silver drachm issued by Rudrasena III, brother and possible co-author of a brief revival in Saka fortunes, although the precise events have been lost to history 380 - ? :

Simhasen : Possibly ruling until 384/5?

382 - 388 :

Rudrasen IV

388 - 395 :

Rudrasimha III : Killed by Chandragupt II of the Guptas.

395 :

The Sakas are finally finished off as a regional power by the Guptas of Magadh, under the leadership of the formidable Chandragupt II. Saka territory is incorporated into the growing Gupta empire. In time the remnants of the Sakas, now without any political power, mix into Indian society. Some scholars believe that they re-emerge in the fifth century as the Indo-Aryan Jats who, from around the seventeenth century dominate the regions of Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |