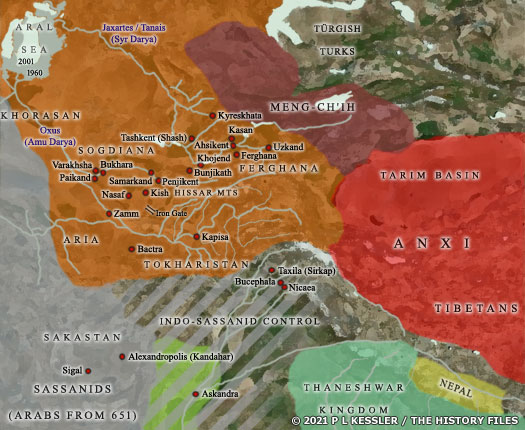

| SOGDIANA The ancient province of Sogdiana (or Suguda to the Persians) lay largely within the easternmost quarter of modern Uzbekistan, along with western Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The River Tanais (otherwise known as the Jaxartes/Iaxartes or Syr Darya), traditionally formed the boundary between Sogdiana and Scythia. In fact, Sogdiana and its western neighbour, Chorasmia, formed the northern edge of civilisation in the ancient world. Beyond them was the sweeping steppeland and marauding tribes of barbarians.

This ancient region had also formed the northern border in Transoxiana for one of the oldest series of states in Central Asia, the indigenous Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, or Oxus Civilisation, and Indo-European tribes had soon integrated into it around the start of the second millennium BC. Forming an Indo-Iranian group of tribes in later centuries, it is these very same people who, within half a millennium, were to be found entering India. Those who remained behind appear to enter the historical record around the sixth century BC, when they came up against their western cousins of the rapidly-expanding Persian empire.

The earliest-known rulers for the region are placed in the 600s BC, with clear links being shown between them and the earliest rulers of Persia (possibly before the latter had fully settled in Persia). In fact, the resemblance between Old Persian and Sogdian languages is one of the supporting pillars for the theory of Persian migration into Iran from Central Asia. The Persians themselves were of Indo-Iranian stock, and it is probably the case that the Sogdian tribes shared that same origin. The large and warlike tribe or confederation of the Massagetae were recorded as bordering the area to the north in 530 BC, less closely-related cousins of the Sogdians and their ilk.

Sogdiana was conquered by the Persians in the mid-sixth century BC during a sweeping wave of conquest by Cyrus the Great. A satrapy or governorship was created to command it from a capital at Marakanda (modern Samarkand). The Persian and Greek satrapy of Suguda and Sogdiana respectively was situated with the sweeping steppeland of Central Asia to its north which, in the Persian period, was peopled by various tribes and groups such as the aforementioned Massagetae, plus the Scythians, with Ferghana to the east, Bactria to the south, Margiana to the south-west, and Chorasmia to the west.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Zoroastrian Heritage, K E Eduljee, and Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps).)

7th century BC :

Later myth ascribes a dynasty of Indo-Iranian rulers to this period, as described in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), a poetic opus which is written down about AD 1000 but which accesses older works and perhaps elements of an oral tradition.

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) The earliest of these mythical Indo-Iranian rulers is Fereydun, king of a 'world empire'. His subjects are the Indo-Iranian tribes of the region while his kingdom of Turan is apparently in the land of Tūr (or Turaj). This can be equated to territory in the heartland of Indo-Iranian southern Central Asia and South Asia, focused mainly on the later provinces of Bactria and Margiana. His main opponents are the Kayanian dynasty of kings of the early Parsua.

c.546 - 540 BC :

The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea).

Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhara, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse. The inference is very clear - whatever control of Turan the Persians may have enjoyed following the death of Afrasiab, it did not last and the lands now have to be conquered properly.

Modern Iran's Makran Coast formed the southern edge of the ancient province of Gedrosia, on what is now the border with south-western Pakistan The heartland of Sogdiana is also drawn into the empire as the province of Suguda, while it is also named Huvarazmish in some Persian inscriptions. The neighbouring region of Ferghana, which gains a defensive fort or city of its own is administered from the Sogdian capital, Marakand. These areas form the north-eastern corner of the Achaemenid empire, with nothing beyond but uncharted wastes full of tribal barbarians.

Persian

Satraps of Suguda (Sogdiana / Huvarazmish) :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Sogdiana (sometimes referred to as Huvarazmish) was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was populated largely by Indo-Iranian tribal groups, the most numerous of which in this particular area were the Sogdians themselves. Under the Persians, the region was formed into an official satrapy or province which, according to the Behistun inscription of Darius the Great, was called Suguda or Sugda (Sogdiana is a Greek mangling of the name).

These eastern regions of the new-found empire were ancestral homelands for the Persians. They formed the Indo-Iranian melting pot from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

Suguda's capital was Maracanda, although little else about Persian-era Suguda is known for certain. The central minor satrapy of Suguda had its southern border along the River Oxus (Amu Darya). The River Polytimetus (the modern River Zeravshan, which feeds into the Oxus from the north of Samarkand) presumably supplied the western border, across which were the nomadic Massagetae. The rest of the western border is uncertain. To the north-east, Suguda was bordered by the territory of the Amyrgians (a Saka grouping), and part of the frontier was marked by the River Jaxartes (Syr Darya).

In the east of Suguda, a subordinate minor satrapy seems to have been that of the Dyrbaeans (Ptolemy's Drybactae). Cyrus the Great placed Spitaces, son of Spitamenes, in charge of the Dyrbaeans, although when writing about them Ctesias mistook them for the Derbicans to the east of the Caspian Sea who were not part of the Achaemenid empire under Cyrus. Stephanus Byzantinus recorded that the Drybaean territory (or Dyrbaioi, to use his phrase) bordered Bakhtrish and Hindush - a pretty broad and vague definition. The only suitable location for these 'eastern Derbicans', the Dyrbaeans, is the modern Afghan province of Badakshan in the far north-eastern corner of the country. Here, in the Monjan Valley, was the only source of lapis lazuli to be exploited at that date. In that case, the minor satrapy of the Dyrbaeans bordered Suguda to the north, Bakhtrish to the west, and Gadara to the south. It lay largely within the arc of the River Panj (or Pyandzh), which feeds into the headwaters of the Oxus to the east of Dushanbe (and today provides part of Afghanistan's border with Tajikistan).

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Campaigns of Alexander, Arrian of Nicomedia (Aubrey De Sélincourt, Ed, Penguin, 1971), from From Democrats to Kings: The Brutal Dawn of a New World from the Downfall of Athens to the Rise of Alexander the Great, Michael Scott, from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, from Persica, Ctesias of Cnidus (original work lost but a section is repeated by Photius in ninth century AD Constantinople), and from External Links: The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

c.546 - 540 BC :

During his campaigns in the east, Cyrus the Great initially takes the northern route from Persis towards Bakhtrish and Suguda to reassure or subdue the provinces. This route probably involves the 'militaris via' by Rhagai to Parthawa. At some point Cyrus builds a line of seven forts to defend his frontier in Suguda and the neighbouring region of Ferghana against the tribal Massagetae to the north, the strongest of these being Kyra or Kyreskhata (Cyropolis - the Greek form of its name).

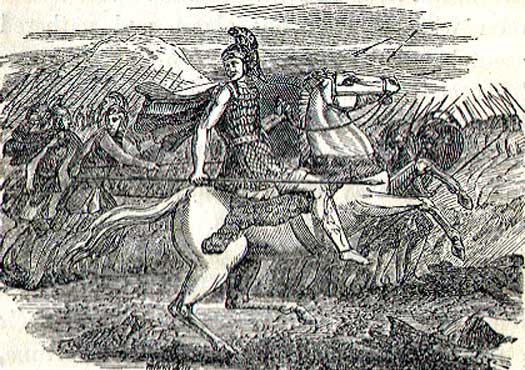

Cyrus the Great freed the Indo-Iranian Parsua people from Median domination to establish a nation that is recognisable to this day, and an empire that provided the basis for the vast territories that were later ruled by Alexander the Great Then he takes the more difficult southern route, destroying Capisa along the way (possibly Kapisa on the Koh Daman plain to the north of Kabul - which is possibly also the Kapishakanish named at Behistun as a fortress in Harahuwatish).

When Cyrus realises he is close to death around 530 BC (according to the somewhat unreliable Ctesias), he appoints Cambyses as his successor. He also makes two appointments to satrapies, placing Spitaces in command over the Dyrbaeans and his brother Megabernes over the Barcanians. Events concerning the Barcanians means that a more realistic dating for this event would be about 515 BC, so Cyrus cannot possibly be the instigator.

fl c.530 BC :

Spitaces : Son of Spitamenes. Satrap of the Dyrbaeans.

516 - 515 BC :

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gadara and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka. Along the way the Sakas are largely defeated and conquered, but probably only along the borders.

One of the three Saka 'nations' is that of the Saka Paradraya. This name breaks down into 'para' and 'draya', the first part meaning 'across' and the latter almost certainly being 'darya' or 'river'. When Persian ruler Darius the Great boasts of the limits of his empire he gives as the north-eastern corner the 'Sakaibish tyaiy para Sugdam' - the Sakas across/beyond Sugdam (Sogdiana), on the other side of the River Tanais (otherwise known as the Jaxartes/Iaxartes or Syr Darya, which forms the boundary between Suguda and Scythia).

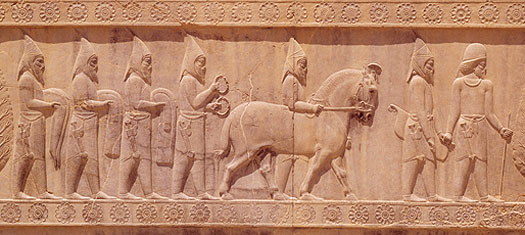

Saka Tikrakhauda (otherwise known as 'Scythians' who in this case can be more precisely identified as Sakas) depicted on a frieze at Persepolis in Achaemenid Persia, which would have been the greatest military power in the region at this time fl 500 BC :

Artabanos : Brother of Darius I. Satrap of Bakhtrish (& Suguda?).

fl 480 BC :

Masistes : Brother of Xerxes I. Satrap of Bakhtrish (& Suguda?).

? - 464 BC :

Hystaspes : Son of Xerxes I. Satrap of Bakhtrish (& Suguda?). Killed?

465 - 464 BC :

Artabanus the Hyrcanian kills Xerxes in collusion with the eunuch of the bedside and subsequently takes control of the empire, ostensibly as a regent for Xerxes' three sons. Artabanus has the murder pinned on the eldest of these, Darius, and has him killed by the youngest son, Artaxerxes. Artaxerxes accedes to the throne before Artabanus attempts to murder him too. In the end, it is Artabanus who dies, but Artaxerxes is forced to defeat the second of Xerxes' sons, Hystaspes, satrap of Bakhtrish (and presumably Suguda too) and his own brother. This brief civil war is ended when Artaxerxes defeats the forces of Hystaspes in battle during a sandstorm.

360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

The River Oxus - also known over the course of many centuries as the Amu Darya - was used as a demarcation border throughout history and was also a hub of activity in prehistoric times - but during this period it flowed right through the heart of the region that was known as Bactria while also providing a sizeable part of Suguda's southern border ? - 329 BC :

Bessus / Artaxerxes V : Satrap of Bakhtrish & Suguda. Murdered Achaemenid Darius III.

330 - 328 BC :

In 330-329 BC Suguda becomes part of the Greek empire despite the efforts of Bessus, self-styled 'king of Asia', to retain at least some of the Persian territories. His claim is legal, since Bakhtrish is traditionally commanded by the next-in-line to the throne, but Persia has already been lost and his loose collection of eastern allies provides nothing more than a sideshow to the main event - the fall of Achaemenid Persia. Still, it takes Alexander the Great two more years to fully conquer the region. One of Bessus' allies is Oxyartes, father to the Roxana whom Alexander marries in 327 BC.

During his conquest of Suguda, following the fall of Bakhtrish, Alexander focuses on the largest and best-defended of seven towns in the region, this being Cyropolis in the Ferghana region (the Kyreskhata of Cyrus the Great). While he takes the other towns, he sends Craterus to pin down the defenders of Cyropolis. Following the quick fall of the other towns, the storming of Cyropolis is led in person by Alexander. Both he and Craterus are wounded but the town and its central fortress are taken. Suguda and Ferghana now belong to the Greeks.

Argead Dynasty in Sogdiana :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Sogdiana was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 305 BC.

Little seems to be known about Persian-era Suguda (Sogdiana), other than the fact that its capital was Maracanda. Located at the north-eastern edge of the empire, and subject to raids across its border by the nomadic Sakas beyond, its borders are known in general terms. Its southern border followed the line of the River Oxus (Amu Darya). The River Polytimetus (the modern River Zeravshan, which feeds into the Oxus from the north of Samarkand) presumably supplied the western border, across which were the nomadic Massagetae. The rest of the western border is uncertain. To the north-east, Sogdiana was bordered by the territory of the Amyrgians (a Saka grouping), and part of the frontier was marked by the River Jaxartes (Syr Darya). Once conquered by Alexander the Great (perhaps only loosely) it was merged in administrative terms with Bactria, while Alexander would soon marry Roxana, the daughter of one of the region's most powerful warlords.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd, G V Shichkina (Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 1994, 8: 83), and from A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith (London, 1873), from Alexander the Great, Krzysztof Nawotka (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from The Cambridge Ancient History, John Boardman, N G L Hammond, D M Lewis, & M Ostwald (Eds), from Sogdiana, its Christians and Byzantium, Aleksandr Naymark (doctoral thesis, Indiana University, 2001), and from External Links: Encyclopĉdia Britannica, and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

328 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

328? BC :

Orepius : Satrap of Sogdiana at the 'gift of Alexander'.

328 BC :

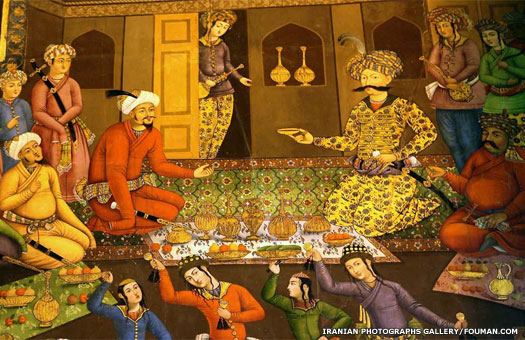

Following the resignation of Artabazus, satrap of Bactria, Clitus is given the post along with command of 16,000 Greeks who had formerly fought under the Persians as mercenaries. He sees this posting as a reduction of his influence and position with Alexander and, at a banquet in the satrap's palace at Maracanda (the capital of the satrapy of Sogdiana, modern Samarkand), the two get into a drunken quarrel. Enduring gross insults from Clitus, in his rage Alexander runs him through with a spear. Almost immediately he deeply regrets the death of his former friend (the scene is well depicted in the feature film, Alexander (2004), although the location is transferred to India).

The route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns are shown in this map, with them leading him from Europe to Egypt, into Persia, and across the vastness of eastern Iran as far as the Pamir mountain range 328 - 323? BC :

Amyntas Nikolaos : Greek satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, & Sogdiana.

328 - 323? BC :

Scythaeus : Greek satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, & Sogdiana.

327 BC :

Against the vehemently strong opinions held by his generals, Alexander proceeds to marry Roxana (Roshanak in her native tongue). She is the daughter of Oxyartes, a Sogdian warlord who had supported Bessus in his attempt to resist Alexander in the east in 329 BC. Oxyartes himself had been one of the defeated defenders of the fortress known as the 'Sogdian Rock' in 328 BC, close to the Sogdian capital at Marakanda. Oxyartes himself is made satrap of Gandhara.

323 - 321 BC :

Following the death of Alexander the Great, some changes come to Chorasmia, Sogdiana, and Bactria. The end of the term of office for Amyntas Nikolaos and his subordinate, Scythaeus, is often given as 325 BC, and sometimes as 321 BC. However, Philip is certainly in place by 323 BC, so this date is used here.

323 - 321 BC :

Philip / Philippus : Greek satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, & Sogdiana, then Parthia.

321 BC :

With Philip being reassigned to Parthia, his replacement in the east is Stasanor the Solian, former satrap of Aria and Drangiana. This new satrap is the brother to Stasander, his replacement in Aria and Drangiana. Perhaps he also has more of a focus towards the Northern Indus territories than the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, as later suggested by events. His territory initially extends as far north as Ferghana, which contains the city of Alexandria Eschate ('the Furthest'), while Stasander also has ambitions.

Eumenes of Cardia, Macedonian general and one of Alexander the Great's 'successors' between whom a series of wars were fought 321 - 312 BC :

Stasanor the Solian : Greek satrap of Chorasmia to Sogdiana, & Nth Punjab (316 BC).

320s BC :

Like the Persians before them, the Greeks under Alexander place the Amyrgian Sakas beyond Sogdiana, across the River Tanais (otherwise known as the Iaxartes, Jaxartes, or Syr Darya, which forms the boundary between Sogdiana and Scythia). This is thanks to their having encountered them after crossing Sogdiana and the Syr Darya in the approximate region of Alexandria Eschate in the Ferghana region ('Eschate' meaning 'the Furthest', possibly modern Khojend, but see the Ferghana introduction). It is generally accepted that they control all of Ferghana (immediately to the east of Sogdiana) and the Alai Valley. Indeed, they may have been relocated onto the plain following their conquest by the Persians.

316 - 312 BC :

The Wars of the Diadochi decide how Alexander the Great's empire is carved up between his generals, but the period is very confused, especially in the east. These provinces appear to be invaded and controlled by the Antigonids for a period, with General Antigonus being responsible for the death of Eudamus. However, at some point in 316 BC, Stasanor the Solian, satrap of Chorasmia, Bactria, and Sogdiana (with Ferghana) seizes the Northern Indus while his brother seizes Parthia. Clearly the two are either working in unison with Seleucus of Babylonia from the beginning or are attempting to stamp their own independent authority on much of the east. Unfortunately, Stasander is removed from office in 315 BC.

312 - 301 BC :

? : Unknown Greek satrap of Sogdiana.

312 - 306 BC :

Bactria is taken by the Seleucids around 312 BC. During the break-up of the empire, it appears that parts of the area become independent, but much of it remains under the control of the Greek satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana. Sophytes is satrap of Bactria, so could he possibly also govern Sogdiana too? Furthermore, given the tradition of Sogdiana's satrap also governing Chorasmia, that too could remain under the control of a single satrap.

The Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC ended the drawn-out and destructive Wars of the Diadochi which decided how Alexander's empire would be divided 305 - 301 BC :

During the Fourth War of the Diadochi, the diadochi generals proclaim themselves king of their respective domains following a similar proclamation by Antigonus the year before (306 BC). Following the death of Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, his territories are carved up by the other diadochi. All of the eastern territories, including Sogdiana, go into forming the empire of the Seleucids.

Macedonian Sogdiana :

During the last of the Wars of the Diadochi, Seleucus was able to expand his holdings with some ruthlessness, building up his stock of Alexander's far eastern regions as far as the borders of India and the River Indus (Sindh). Appian's work, The Syrian Wars, provides a detailed list of these regions, which included Arabia, Arachosia, Aria, Armenia, Bactria, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia (as it was known) by 301 BC, Carmania, Cilicia (eventually), Drangiana, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Media, Mesopotamia, Paropamisadae, Parthia, Persis, Sogdiana, and Tapouria (a small satrapy beyond Hyrcania), plus eastern areas of Phrygia.

Once safely under Seleucid control after the conclusion of the Greek wars, Sogdiana was supposedly governed by Macedonian satraps from Bactria (see below). The capital was at Marakanda (later Samarkand). The descendants of many of these satraps became independent kings, after Bactria had been cut off from the Seleucids by Parthian incursion into central Persia. The Bactrian kingdom consisted of the core provinces of Bactria and Sogdiana. Located in one of the richest and most urbanised of regions, it quickly blossomed into a large eastern Greek empire, but continual internal discord and usurpations saw it progressively fragmented and vulnerable to outside conquest. The eastern section was almost permanently separated from Bactria and came to be known as the Indo-Greek kingdom.

The chronology of the Indo-Bactrian rulers is based largely on numismatic evidence (coinage). There are few written accounts, and other records are relatively sparse, while frequent internecine conflicts makes the facts even harder to pin down, so dates are rarely reliable. Some possible kings are known only from a few coins, and the interpretation of these can sometimes be very uncertain. The word 'supposedly' is used above in connection with Sogdiana being governed from Bactria simply because there is very little evidence to prove it. Sogdiana is indeed included in the list of eastern provinces that were secured by the Seleucids in the campaign of 305 BC. It may well have remained an administrative division during the early years of post-Alexandrine governance of the east, but a campaign in 283-281 BC and a lack of mentions afterwards paint a distinct picture of a lost region, and perhaps one that was not particularly secure beforehand.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by David Kelleher, from The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau, Jeffrey D Lerner (1999), from Sogdiana, its Christians and Byzantium, Aleksandr Naymark (doctoral thesis, Indiana University, 2001), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Encyclopædia Britannica, and Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, Marcus Junianus Justinus (Rev John Selby Watson, Trans, 1895), via Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum, and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991) has been followed.)

c.294 - 293 BC :

Demodamas : Seleucid satrap (governor-general) of Bactria & Sogdiana.

c.294 - 293 BC :

A former general under Seleucid rulers Seleucus I Nicator and Antiochus I Soter, Demodamas serves twice as satrap of Bactria and Sogdiana. During this time he undertakes military expeditions across the Syr Darya to explore the lands of the Sakas, repopulating Alexandria Eschate ('the furthest', possibly modern Khojend) in Ferghana in the process following its earlier destruction by barbarians.

His journeys of exploration take him farther than any other Greek, barring perhaps Alexander himself, and his records of what he finds provide an important platform for later Roman writers.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi c.293 - c.281 BC :

? : One or more unknown Seleucid satraps.

283 - 281 BC :

During his time campaigning and exploring the lesser-known lands to the north of Bactria, Demodamas directs his attentions towards nomads who are inhabiting the lands to the north of Sogdiana. These would be Sakas (quite possibly related to the Massagetae of Cyrus the Great's time), often unruly and hard to govern effectively while they occupy the sweeping steppe to the north of the Syr Darya.

Whether Demodamas has to direct any efforts towards securing Sogdiana itself remains unclear. It seems to fall off the historical record after this point, at least as far as the Greeks are concerned, suggesting that it is largely lost or abandoned while the Greeks focus on far more lucrative and promising expansion to the south. However, some events later in the century seem to point towards Sogdiana still being connected to Greek events in Bactria, however loosely.

c.281 - 280 BC :

Demodamas : Seleucid satrap for the second time.

c.280 - 256 BC :

? : Unknown Seleucid satraps.

256 - 248 BC :

Diodotus I Soter : Seleucid satrap. Declared the Bactrian kingdom.

256 BC :

Diodotus declares independence from Seleucid Greek rule at the same time as the satrap of Parthia. It may even be the actions of Andragoras of Parthia which force the hand of Diodotus I Soter, since there is little immediate chance of Seleucid retaliation. However, although the written evidence is confused and somewhat contradictory, it is more likely to happen the other way around. Bactria declares independence and Parthia follows. Diodotus now rules the former provinces of Bactria (to the south), Sogdiana, Ferghana (modern eastern Uzbekistan), and Arachosia (modern Kandahar). It is Strabo who confirms that Sogdiana at this time remains a Greco-Bactrian possession.

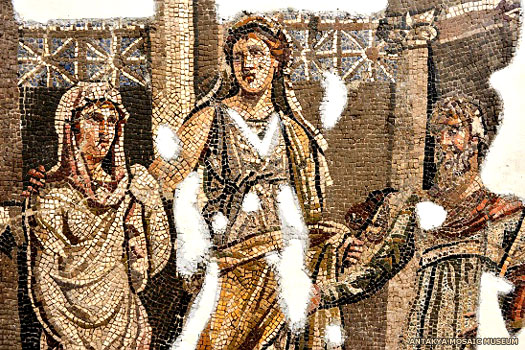

Although the mosaics exhibited today in the Antakya Mosaic Museum in Turkey generally date to the first to fifth centuries AD, Seleucid Antioch of the third to first centuries BC would have been just as grand a city 248 - 235 BC :

Diodotus II : Son. King in Bactria.

c.235/230 BC :

Diodotus II of Bactria is overthrown by Euthydemus, possibly the satrap of Sogdiana. The date is uncertain and Strabo puts forward 223/221 BC as an alternative, placing it within a period of internal Seleucid discord.

235 - 200/195 BC :

Euthydemus I Theos : Satrap of Sogdiana? Overthrew Diodotus.

c.220 BC :

The realm of Euthydemus of Bactria is a large one, perhaps still including Sogdiana and Ferghana to the north (although this is highly questionable), and Margiana and Aria to the west. There are indications that from Alexandria Eschate in Ferghana the Greco-Bactrians may lead expeditions as far as Kashgar (a little under three hundred and twenty kilometres due east of Ferghana), and Urumqi in Chinese Turkestan. There they would be able to establish the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC.

Even more remarkably, recent examinations of the terracotta army have established a startling new concept - the terracotta army may be the product of western art forms and technology. An entire terracotta army plus imperial court are manufactured using five workshops and a form of human representation in sculpture that has never before been seen in China. Archaeologists today continue the process of discovering new pits and even a fan of roads leading out from the emperor's burial mound, one of which, heading west, may be a sort of proto-Silk Road along which Greek craftsmen may be travelling (Marakanda being a key location along the Silk Road from the moment of its establishment).

Marco Polo's journey into China along the Silk Road made use of a network of east-west trade routes that had been developed since the time of Greek control of Bactria 208 - 206 BC :

Euthydemus repulses an effort at the re-conquest of Bactria by the Seleucid ruler, Antiochus III. Following defeat at the Battle of the Arius, Euthydemus successfully resists a two year siege in the fortified city of Bactra before Antiochus finally decides to recognise his rule in 206 BC. He offers one of his daughters in marriage to Euthydemus' son, Demetrius, but it may also be at this time that Euthydemus refers to great hordes of nomads accumulating on the northern borders, possibly meaning that Sogdiana has been removed from his control, and posing a threat to both their domains - Bactria and the Seleucid empire.

fl c.160s BC? :

Hyrcodes : Known from a few coins only. King in Sogdiana?

167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes the former province of Aria (now northern Afghanistan) from the Greco- Bactrian kingdom. It seems possible that Aria (and possibly a rebellious Drangiana too) had already been conquered once by the Arsacid Parthians, with the Greco-Bactrians recapturing it, probably during the reign of Euthydemus I Theos. During the reign of Eucratides I the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

The last statement raises the question of who in Sogdiana is standing against Eucratides. There exist a few coins which are minted under the command of one Hyrcodes, an otherwise unknown individual (although the name may not even be that of a ruler). There is much speculation about whether 'he' is based in Bactria or in Sogdiana (possibly at Marakanda, modern Samarkand), and whether he commands in the second or first century BC.

The successor to Antimachus I of Bactria was Eucratides I, with this silver tetradrachm being minted in his image at some point during the twenty-six years or so of his reign Equally unknown is whether he is an Indo-Greek himself, or possibly a Saka with Greek influences, although Sogdiana's drift towards following nomadic culture in this period would suggest the former - an Indo-Greek who is opposing his peers in Bactrian from a position of relative isolation and safety in the north. Despite another claim that he may even be a Greater Yuezhi leader or vassal of the later decades of the second century BC, the Indo-Greek theory makes the most sense. The result is that Hyrcodes is unlikely to survive the imminent Saka and Greater Yuezhi invasions of Sogdiana.

Post-Greek Sogdiana :

Following the final termination of Greek rule in Bactria around 130 BC - and seemingly for at least some decades before it too - Sogdiana's history becomes very hazy. Scholars have not particularly been able to reach a consensus about what was happening in the region even during the Greek kingdom period, let alone afterwards. Very often the only evidence at all is primarily numismatic, with some regional coins being produced bearing the name or likeness of minor tyrants, usually in the Greek style which remained the one to follow for some centuries.

In numismatic terms, very few Greco-Bactrian coins have been found in Sogdiana. The quality of these and regional imitations gradually reduced between the first century BC and the fourth century AD, with the silver content worsening. Architecturally, there seems to be very little monumental Greek architecture, despite neighbouring Bactria enjoying a boom in construction. In fact, despite there remaining an element of Greek influence, previously established Indo-Iranian tradition seems to have enjoyed a revival. Sogdian script was used in place of Greek, developed out of Achaemenid courtly Aramaic. Sogdian fortifications which were erected during this period also followed established Indo-Iranian styles, and Sogdian clothing was traditional Central Asian in style rather than Greek. In fact, while Bactria experienced a mix of these traditions along with Indo-Greek influences, Sogdian style seemed to have been influenced only by nomadic styles.

Two main views remain possible: that the Greco-Bactrian kingdom included Sogdiana at least during the third century BC before barbarian incursions removed it from their sphere of control; or that Sogdiana was lost to the Greeks very soon after the death of Alexander, with the Greeks in Bactria focussing on that satrapy and with close integration with the Indo-Greek territories both during the period of Mauryan ascendancy (from 305 BC) and during its decline (seemingly from 256 BC when the Greco-Bactrians declared independence from the Seleucid empire). The latter view sees Sogdiana largely abandoned by Greek control but still heavily influenced by its culture, and politically splintered amongst several minor principalities such as those of Bukhara and Vardana.

There is simply not enough evidence available to decide either way, but a vague picture can be discerned. Holt suggests quite reasonably that Alexander never really consolidated his conquest of Sogdiana, instead relying on local concessions and the taking of a Sogdian bride (Roxana) to settle the situation there so that he could move on with his campaigns. After his death, the unstable situation there simply dissuaded the Bactrian satraps from taking much of an interest - even if their abilities were (sometimes) equal to the task. The reign of Eucratides I in Bactria can certainly be taken as a final cut-off point thanks to confirmation that the kingdom is engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Sogdiana, its Christians and Byzantium, Aleksandr Naymark (doctoral thesis, Indiana University, 2001), from Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Frank L Holt (1989), from The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3, E Yarshater (Ed), from The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau, Jeffrey D Lerner, and from External Links: Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, Marcus Junianus Justinus (Rev John Selby Watson, Trans, 1895), via Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum, and Kidarites (Encyclopaedia Iranica), and Turkic History, and Iron Gates of Sogdiana (Uzbekistan Travel).)

c.165 BC :

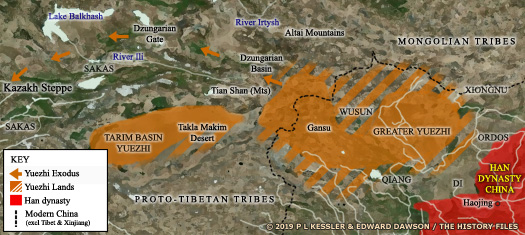

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement.

The Greater Yuezhi were defeated and forced out of the Gansu region by the Xiongnu, and their migratory route into Central Asia is pretty easy to deduct from the fact that they chose to try and settle in the Ili river valley below Lake Balkhash c.155 BC :

The Sakas (in the form of the Amyrgian branch) are displaced from Ferghana by the Greater Yuezhi. They are undoubtedly pushed towards neighbouring Sogdiana, where they are dominant enough to take control of the region, displacing whichever regional tyrants may have arisen or becoming their overlords. This is an event that is connected with the migration of the Greater Yuezhi across Da Yuan (the Chinese term for Ferghana), following another defeat, this time by an alliance of the Wusun and the Xiongnu. The Greater Yuezhi are forced to move again, causing other tribes also to be bumped out of position.

These mass migrations of the second century BC are confused and somewhat lacking in Greek and Chinese sources because the territory concerned is beyond any detailed understanding of theirs. Whatever the reason, the Saka king transfers his headquarters to the south, across the Hanging Passage that leads to Jibin. This is part of a southwards trend for the Sakas, and by approximately the mid-first century BC, Saka kings appear in India.

140 - 130 BC :

Sakas have long been pressing against Bactria's borders. Now, following a long migration from the borders of the Chinese kingdoms, the Greater Yuezhi start to invade Bactria from Sogdiana to the north. Initially, Saka elements who are already in Bactria become vassals to the Greater Yuezhi.

Suvars (or Subars), a horse husbandry tribe known from the environs of Sumerian Mesopotamia (if in fact they are the same group - doubtful given the time span involved), now gain renewed prominence when they join the 'Tokhars' (Tokharoi) and Ases (Asioi) in the nomadic conquest of Sogdiana and Bactria about this time. The Ases have been equated with the Ases of the Pontic-Caspian steppe in the sixth century. They may be the same group, although this is debatable. A case can be made, however, by this nomadic group returning northwards to be swept up in early Turkic migrations towards the Caspian Sea - the Suvars seem to follow the very same course.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi At around the time of the death of the Indo-Greek King Menander in 130 BC, the Greater Yuezhi overrun Bactria and end Greek rule. Heliocles may possibly invade the western part of the Indo-Greek kingdom, as there are strong suggestions that the Eucratids continue to rule there, especially in Heliocles' presumed son, Lysias.

Following the Greater Yuezhi invasion and conquest of Sogdiana and Bactria, the city of Ai Khanum (its modern name) on the Amu Darya in Bactria goes into unrecoverable decline. Founded (if the identification is correct) as the city of Alexandria on the Oxus, its modern Uzbek name means literally 'Lady Moon'. On the northern bank of the river the fortress religious centre of Takht-i Sangin (now in southern Tajikistan) survives and flourishes until the late Kushan period.

126 BC :

The Chinese envoy, Chang-kien or Zhang Qian, visits the newly-established Greater Yuezhi capital of Kian-she in Ta-Hsia (otherwise shown as Daxia to the Chinese, and Bactria-Tokharistan to western writers) and the rich and fertile country of the Bukhara region of Sogdiana. His mission is to obtain help for the Chinese emperor against the Xiongnu, but the Greater Yuezhi leader - the son of their leader who had been killed about 166 BC - refuses the request. Kian-she can reasonably be equated with Lan-shih or Lanshi, but the question of whether this is the Bactrian capital of Bactra (modern Balkh) seems to be much more controversial. It does seem to be likely though, despite scholarly objections.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards Eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahanas of India 115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and around Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhara. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies.

c.50 BC :

Having settled in Sogdiana and Bactria, the Greater Yuezhi have effectively rechristened these provinces as Tokharistan. Now, a century-or-so-later they have united under a single leadership, that of the Kushan tribe. Around this time they capture the territory of the Sakas in what will one day become Afghanistan, and have probably already caused the downfall of Indo-Greek King Hermaeus, conquering Paropamisadae in the process.

fl 1st cent AD :

Phseigaharis? : Known only on coins. Local ruler in Sogdiana. Greater Yuezhi?

1st century AD :

A few coins have been found which are minted (probably) in the first century AD by one Phseigaharis. The coins all come from the prosperous Kashka Darya valley of the western Pamir mountain range immediately south of Marakanda (Samarkand, with the valley now being in the region of Qashqadaryo in eastern Uzbekistan). Most of the coins do not permit any especially accurate dating, or even an accurate location, as they are generalised Greek types.

One more recent find carries an Aramaic legend behind the ruler's head on the obverse as well as a Greek legend. This pinpoints the mint to that at Marakanda, while the ruler's hair style and 'ethnic' characteristics strongly suggest a first century AD date. Otherwise unknown except for these coin finds, Phseigaharis can be classed as a local ruler in Sogdiana, possibly a member of the Greater Yuezhi or one of their regional vassals.

The Pamir Mountains in the east of modern Tajikistan became a border region for the post-Greek regions of Sogdiana, and have produced some interesting archaeological finds over the years c.30 - 50 :

The unity in coinage designs across the Greater Yuezhi territories has been relatively short-lived. The rise of the Kushan tribe and its formation of an empire based in Bactria-Tokharistan seemingly replaces this with its own new monetary style. As a result coinage in Sogdiana declines steeply while that of Bactria remains prosperous. Apparently lying outside the empire, for the next two centuries the coinage of the Zaravshan Valley around Marakanda (Samarkand) imitates the Alexander style used in the Ashtam group (second century AD) and by Hyrcodes (of Macedonian Sogdiana, perhaps circa 160 BC?).

Ceramic production and sophistication also declines, apparently quite abruptly, leaving Sogdiana an under-developed backwater supported only by 'pre-Silk Road' trade with the Han kingdom. Cities decay in the Zaravshan Valley, close to Marakanda, including Afrasaib-Samarkand, Kuldor tepe, Durmen tepe, Kurgan tepe, and Varaksha. Large sections of their territory which had previously been inhabited are now abandoned, dwellings left empty. Only the Kashka Darya basin to the south of Marakanda escapes the decline, probably acting as a cultural refuge for Sogdiana as a whole.

At the founding of the Kushan empire, a long corridor of territory is seized by the Kushans between Bactria-Tokharistan and the middle course of the Amu Darya. This serves to create a Kushan barrier along the entire southern and western Sogdian border. The inference that can be drawn from the lack of Kushan empire coinage in Sogdiana (extremely rare), and the lack of any other apparent benefits of empire, is that Sogdiana is isolated deliberately or otherwise by this barrier, cut off from the Parthian empire and the west. A Kushan fortification wall which shuts the Iron Gates would suggest that the barrier is deliberate.

The Iron Gates (shown here), are part of a narrow but popular linking route between Sogdiana and Bactria in the Baba-tag Mountains (close to modern Derbent) fl 2nd cent AD :

? : Unnamed ruler in Marakanda known only from coins.

2nd century :

The coins of the Ashtam group are minted in Marakanda (Samarkand) during this century. They continue the tradition of imitating Alexander styles, with a representation of an archer on the reverse. Unfortunately the identity of the local ruler shown on them cannot be ascertained. Sogdiana's decline continues throughout this century, reaching its lowest point in the third century.

c.260 :

The vassal kingdom of Margiana is formally annexed to the Sassanid crown by Shapur I. The name of the vassal king here is unknown (unless Ardashir is still alive). Now Shapur places his own son, Narseh, as governor of the province of Hind, Sagistan, and Turgistan. Margiana is part of this broad territory, falling within the Sagistan section which itself is named for the Saka groups which formerly dominated here.

This could also be the point at which Shapur seizes Sogdiana and makes it part of the empire. Much of it is occupied for a time (Marakanda, for instance - modern Samarkand), while part is occupied for a longer period (Bukhara especially). It seems that the new masters of Iran have, at the same time as Kushan power is on the wane, broken through a Kushan barrier that has until now isolated Sogdiana.

fl 200s/300s? :

? : Unnamed 'ruler' in south-western Sogdiana.

c.200s/300s :

In Sughd (Sogdiana) some time between the second and fourth centuries AD, a local ruler in the south-western region mints his own coins. They derive from imitations of early Seleucid drachms of the Alexander type, with the derivation coming via the reverse and its highly stylised depiction of Zeus bearing an eagle. The lettering includes the title 'ruler', but only a handful of these coins have been discovered and the ruler's name is not known.

The successor to Antimachus I of Bactria was Eucratides I, with this silver tetradrachm being minted in his image at some point during the twenty-six years or so of his reign - such coins would remain in circulation for several more centuries, often being overstamped with the initials of new, more local rulers 312 - 313 :

The 'Ancient Sogdian Letters' form the first documentary evidence to show that things are changing in Sogdiana. The recent rise of the Sassanids in Iran and the subsequent eclipsing of the Kushans may have something to do with this. These letters show the existence of a large network of merchants from the cities of Sogd (Sogdiana) now in the Tarim Basin (home of the Tocharians) and beyond. With the removal of the Kushans, Sogdians have been able to force their way into the trade routes which have already been established between India and China via the Tarim Basin.

c.350/375 :

Having been subjugated by the Gupta kings, the rump eastern Kushan state is soon conquered by the invading Kidarites. They, in turn, claim to be the rightful successors of the Kushans and Kushanshahs (to the south of Bactria). Any possible survivors in the west are probably displaced by the Hephthalites.

It is probably not coincidental that the style of regional coins in Sogdiana suddenly changes in the second half of the fourth century, or towards the end of it. Coins which have imitated Greek types for over four centuries - especially the tetradrachms of Euthydemus I, former Greek satrap of Sogdiana - are no longer issued, being replaced with coins of quite a different appearance.

These are small silver coins with a head-and-shoulders representation in the Transoxianan style of a ruler in a diadem on the obverse, and on the reverse an altar with a blazing fire and a circular legend in Sogdian in which only the title MR'Y can be read. Similar coins are issued in copper. Both are ancestors of a new generation of coins which are linked to Bukhara right up to the seventh century (possibly due to the rise there of a ruling elite which survives until the Islamic invasion).

fl c.350s? :

MR'Y : Initials on a coin of a ruler in Sogdiana. With the opening of the trade routes to India and China (the latter undoubtedly including the Tarim Basin Tocharians), the once shrunken and backward Sogdiana is booming again. A sudden and rapid improvement in development take place, with the surviving cities growing rapidly, and new defensive lines being put up that demonstrate the gaining of significant new territories.

This example of the Tarim Basin mummies had the usual distinctive European features, along with a full head of red hair which had been braided into pony tails, and items of woven material which match similar Celtic items 441 - 457 :

A Kidarite conquest of at least part of Sogdiana seems to be safely attested by coins from Samarkand, bearing on the obverse the schematised portrait of a ruler with the Sogdian legend kyδr. On typological and metrological grounds these coins can be assigned to the fifth century. Similar coins also begin to be issued from nearby Bukhara.

fl c.441? :

? : Unnamed and unrecorded Kidarite (?) ruler in Sogdiana.

fl c.450? :

? : Unnamed and unrecorded Kidarite (?) ruler in Sogdiana.

fl c.457? :

? : Unnamed Kidarite (?) ruler in Sogdiana.

fl c.470s? :

? : Unnamed Kidarite (?) ruler in Sogdiana. The last (by 509)?

457 - 509 :

Hypothetically this conquest can be connected with the interruption of Sogdian embassies to China between 441 and 457, and with a piece of information in the Weishu (formerly dated to 437, but actually referring to 457) mentioning an earlier capture of Samarkand by the Xiongnu. The ruler of this captured part of Sogdiana in 457 is the third of the new dynasty. This (possibly) Kidarite dynasty maintains its hold over Samarkand until 509, after which date embassies from Samarkand are incorporated into Hephthalite ones.

Post-Greek

Principalities (Sogdiana) :

The view of Post-Greek Sogdiana and neighbouring post-Greek Ferghana remains confused. It seems likely Sogdiana was largely abandoned by the Greeks very soon after the death of Alexander the Great, with the Greeks in Bactria focussing on that satrapy, more interested in closer integration with the Indo-Greek territories both during the period of Mauryan ascendancy (from 305 BC) and during its decline (seemingly from 256 BC when the Greco-Bactrians declared independence from the Seleucid empire). Even so, Sogdiana remained heavily influenced by Greek culture, while being politically splintered amongst several minor principalities such as those of Bukhara, Varakhsha, plus several others, all of which barely enter the historical record.

The Sassanid ruler, Shapur I, seems to have conquered Sogdiana around AD 260 while subjugating a good many eastern regions as the Kushans in Bactria waned. If not then, it certainly happened not much later. Much of Sogdiana was occupied for a time (Marakanda, the capital, for instance), while part was occupied for a longer period (Bukhara especially). How long this situation endured is unknown (around 375 and the Kidarite invasions seems likely), but Sogdiana was not in Sassanid hands by the time the Sassanids were conquered by Islam in the seventh century.

The principality of Vardana (or Wardana) lay in the northern part of the Bukharan oasis, which Chinese sources sometimes referred to as Lesser Bukhara. Vardana was independent of Bukhara in the second quarter of the seventh century AD (part of the reason for assuming that Sassanid power no longer held sway here). It minted its own coins, which carried the sign of a cross on the reverse. The cross corresponds to the Nestorian Christian cross of Central Asia, making this principality a Christian one. The general style was a regional one which had first appeared in the late fourth century AD, albeit without the cross, replacing the previous Greek types.

Other independent towns included at least two separate principalities to the east of Samarkand, those of Penjikent and Ustrushana, both of which also became wealthy through trade with China. Then there were Paikand and Maimurgh, while Kish (Kash, Kesh, or Ke) and Nasaf were relatively politically minor, if prosperous, cities on the central Sogdian plan between the Hissar Mountains to the south of Ustrushana and the Oxus. Nasaf was the largest town in Sogdiana at the start of the fifth century, but was soon surpassed. Both cities were notable for being allied to Bukhara in the coalition of 676, which was quickly defeated by the Arabs. Penjikent and Varakhsha are relatively unusual in having been subjected to detailed archaeological examination. Many other sites have only been surveyed, not excavated.

At the end of that period, around the middle of the seventh century, the Bukharan mint switched to the Chinese cash model and started casting coins. This was very close in time to China's short-lived partial occupation of Transoxiana which ended in 665. The initial coins were simple imitations of the Kaiyvan Tongbao coins which were minted between 621-907, but then a Bukharan tamgha was added to the reverse and later two types were issued carrying Sogdian inscriptions - the Bukharan tamgha and the sign of a cross. The latter is highly suggestive of the badge of a realm, that of Vardana. The 'coin language' being used here suggests that the previously independent principality was now united with Bukhara under the sway of one ruler. Written sources plainly state that Vardan Khuda had seized power in Bukhara by pushing aside the legitimate heir, usurping the throne and occupying it for twenty years until Qutaiba ibn Muslim, Umayyad governor of Greater Khorasan, expelled him in 708/9, ending regional independence.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from ONS No 206 (Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, Winter 2011), from The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3, E Yarshater (Ed), from History of Humanity: from the seventh century BC to the seventh century AD, Joachim Herrmann, Erik Zürcher, & Ahmad Hasan Dani (International commission for a history of the scientific and cultural development of mankind, History of Mankind, Unesco, 1994), from Tarik-e Bokara, Abu Bakr Ja'far Naraki M-T Modarres Razawi (Ed), Tehran, 1972), from History of Civilizations of Central Asia (Volume 3), Ahmad Hasan Dani (Motilal Banarsidass, 1999), and from External Links: Bukhara History Part 5: Bukhara under the Arabian Conquest (Advantour), and The Silk Road, and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

552 :

The Western Göktürks expand their dominion towards Chorasmia and Sogdiana, right up against the borders of Persia's eastern territories (Ferghana is also taken). The Hephthalites are defeated in Kushanshah territory in what one day will become Afghanistan by an alliance of Göktürks and Sassanids, and a level of Indo-Sassanid authority is re-established in the region for the next century. The western khagans set up rival states in Bamiyan, Kabul, and Kapisa under the authority of the viceroy in Tokharistan, strengthening their hold on the Silk Road.

As was often the case with Central Asian states that had been created by horse-borne warriors on the sweeping steppelands, the Göktürk khaganate swiftly incorporated a vast stretch of territory in its westwards expansion, whilst being hemmed in by the powerful Chinese dynasties to the south-east and Siberia's uninviting tundra to the north 581 - 590 :

The Western Göktürks are now following their own westwards expansionist policy. As part of that policy, they are able to cross the Amu Darya, where they come into conflict with their former allies, the Sassanids. Much of Tokharistan (former Bactria, including Balkh) remains a Göktürk dependency until the end of the century. By inference, Sogdiana to the north of Bactria is also theirs.

The western Göktürk period is of particular importance in Sogdiana and for the Sogdians. The Göktürks destroy local dynasties such as the dynasty of Paikand, but the integration of the Sogdians into the Göktürk state allows for an expansion of Sogdian culture and commercial activities. The Sogdians start to colonise regions further to the east, including Semirech'e, thereby setting up their expansion into China's western periphery while also enriching the Göktürk empire.

The western extension of the same trading networks allows silk to be exchanged with the Sassanids from China where it has been received as tribute from the Tang due to Göktürk military successes. This also allows for the opening of the Khurasan Road, creating an integration of the Sogdian network into a Sassanid one.

600s - 682 :

While Sogdians have become the high administrators of the Western Göktürk state, the Sogdian language has also become the lingua franca of the Göktürk empire. It expands far into the east towards China, even lending its script to Old Turkic and many subsequent Turkic and Mongolian languages. In turn, the Göktürk nobility has become part of Sogdian society, with marriages between the families of the kings of Samarkand and that of the Göktürk khagan. Penjikent has a Turkic ruler at the beginning of the seventh century.

By the beginning of the seventh century AD, Göktürk power in southern Central Asia was waning while the Sassanids had established a degree of control over the southernmost parts of this region, and various city states had emerged in Sogdiana It appears that, by now at least, there are several local lords in the Bukhara oasis, especially in the towns of Samarkand, Paikand, Vardana, and Varakhsha. Both Paikand and Varakhsha are mentioned in the by Tarik-e Bokara, Abu Bakr Ja'far Naraki as residences of the rulers, but whether they are local rulers only or rulers of the entire oasis is still unknown. Some form of unity in the oasis is implied by the coinage, the extensive irrigation system, and the long protective walls around the settled and cultivated areas.

Samarkand (Sogdiana) :

Samarkand was occupied (possibly) as early as the eighth century BC, probably as a consequence of a change in the course of the River Oxus and the abandonment of former settlements. The same circumstances, during a period of climate change, had ended the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex along the River Oxus between 2000-1700 BC and resulted in large-scale migrations. Following this, the region was occupied largely by Indo-Iranian tribes which remained independent until their sixth century BC conquest by fellow Indo-Iranians, the Achaemenid Persians. They formed the satrapy of Sogdiana, which was inherited by the Greeks.

The city of Samarkand gained its name from the Sogdian phrase, 'rock town', which refers directly to a stone fort. This was probably one of the earliest solid structures to be erected on the site, possibly by the Persians. The original form of the name was adopted or adapted by the Greeks of Macedonian Sogdiana as Marakanda. Subsequently, during the gradual infringement of Turkic tribes into the region, Marakanda became Samarkand, with the town of Maimurgh on its immediate south-eastern flank. In Uzbek the name is shown as Samarqand, with Samarcand as another variation. Today the city sits in a large oasis in the valley of the River Zerafshan, within the borders of Uzbekistan.

The historical section of modern Samarkand consists of three main parts. To the north-east there is the site of the ancient city which was destroyed by the Mongol armies of Chingiz Khan in the thirteenth century AD. This is preserved as an archaeological reserve with excavations that have revealed the ancient citadel and fortifications, the ruler's palace, and residential and craft quarters.

There are also remains of a large mosque built between the eighth to twelfth centuries. To the south are architectural ensembles and the medieval city of the Timurid era, at which time Samarkand was at the height of its achievement.

(Information by Peter Kessler, from The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau, Jeffrey D Lerner (1999), the Guidebook to the History of Samarkand, from Sogdiana, its Christians and Byzantium, Aleksandr Naymark (doctoral thesis, Indiana University, 2001), from ONS No 206 (Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, Winter 2011), from Place Names of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites, Adrian Room (Second Ed, London, 2006), from The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3, E Yarshater (Ed), from History of Humanity: from the seventh century BC to the seventh century AD, Joachim Herrmann, Erik Zürcher, & Ahmad Hasan Dani (International commission for a history of the scientific and cultural development of mankind, History of Mankind, Unesco, 1994), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Encyclopĉdia Britannica, and Bukhara History Part 5: Bukhara under the Arabian Conquest (Advantour), and Unesco World Heritage Convention, and The Silk Road, and Encyclopaedia Iranica.).

? - c.640 :

Shishpin : Ikhsid of Samarkand.

c.650s :

Samarkand is certainly the largest Sogdian town at this time, and its princes now start claiming the title of 'king' (malek, ekid). It remains surrounded by many independent principalities which send their own ambassadors to the Chinese court, such as Bukhara, Estikan, Kabudan, Kish, and Panjikent.

c.640 - 670 :

Varkhuman / Vargoman : Ikhsid of Samarkand.

659 - 665 :

A seemingly partial occupation of Transoxiana by Tang dynasty Chinese is effected in 659, but is ended in 665. This is part of a Tang effort to defend its western approaches after centuries of barbarian incursions and also to provide buffer districts between it and the strife that is engulfing Central Asia. The protectorate of Anxi remains in command of the Tarim Basin and probably also the approaches into China to the basin's immediate north.

654 :

Following the Islamic conquest of Sassanid Persia in 651, initial raiding parties have been sent out into the eastern territories on a regular basis. The idea is to sow disruption, force weaker states or cities to reveal themselves as being ripe for conquest, and to exact tribute and plunder freely. In this year one such raid strikes the city of Maimurgh. The attack, and probably others of the same year, prove to be the final straw for the natives. They rise together against the invaders and virtually drive them back into Persia proper. It may be the seemingly unnamed king of Kabul who is amongst the leaders of the retaliation against Islam.

676 :

The brief Umayyad governorship of Greater Khorasan by Sa'id ibn Uthman is largely marked by one of the few major expeditions of the post-Abdallah ibn Rabi period. He strikes into Sogdiana to defeat a coalition of city states there, which includes Bukhara (still under the regency leadership of the khatun), Kish, and Nasaf, plus an alliance of nomadic Turks. The Arab general goes on to occupy Samarkand and take fifty noble sons hostage, only later to have them executed in Medina.

682 :

The Western Göktürk empire has disintegrated rather quickly after gaining its initial quick successes, losing power in the middle of the seventh century and, by 682, ceasing to exist. Even before that, the Tang of China have started to establish a protectorate in Central Asia, known as the protectorate of Anxi which expands westwards out of its initial focus in the Tarim Basin from 640.

Despite a restoration of Turkic power at the beginning of the eighth century, the Tang hold nominal power in the region until 751. However, the region is coming under ever-increasing attacks by the Umayyad governorate of Greater Khorasan, especially in the 670s onwards. Bukhara is subdued in 674, although subsequent governors fail to follow up with their own conquests.

c.688 :

Bukhara would appear to be seized at this time by the ruler of its chief rival in the region, the city state of Varakhsha. Any unity between the principalities in Sogdiana also vanishes around this time, perhaps due to this act or prompting it. Alliances form and are abandoned, and inter-dynastic marriages are obtained. The picture is one of small states vying openly for superiority.

708/709 :

Qutaiba ibn Muslim, Umayyad governor of Greater Khorasan, expels Vardan Khuda from Bukhara. The same governor is also claimed as the conqueror of Chach, Ferghana, and Khojend, presumably during this same period.

? - 709/710 :

Tarkun / Tarkhun : Ruler of Samarkand. Overthrown for being pro-Islam.

c.710 - 722 :

Qutaiba ibn Muslim, Umayyad governor of Greater Khorasan, confirms in his position the new Sogdo-Turkic ruler of Samarkand, Ghurak. This individual has usurped the throne after killing Tarkhun, creating family feuds which drive Tarkhun's sons to the court of Dewashtich (or Divasti), son of Yodkhsetak and sur or ruler of Penjikent. Dewashtich, like other Sogdian princes, has claimed to be ruler of Samarkand, and this makes his claim a stronger one.

Along with Karzanj, ruler of Paikand, Dewashtich is mentioned as the leader of an anti-Islam rebellion in Sogdiana in 720. Together the pair liberate Samarkand, holding it in the face of relatively weak attempts to regain it. Dewashtich has a famous last stand in 722 from his mountain fortress of Mugh, whose details are known from the very vivid accounts given in the Documents of Mugh Mountain.

The defeat of Dewashtich marks the beginning of the formal accession of Transoxiana into the Islamic empire, and soon results in the increasing Islamic control of the eastern regions as well. Among other things, this causes the break-up of the Sogdian commercial network, and ultimately an integration of Sogdiana into the Islamic empire.

709/710 - c.712 :

Gurak / Ghurak / Ughrak : Ruler of Samarkand. Approved by Islam. Driven out.

c.712 :

Probably frustrated by the endless bickering regarding superiority between the Sogdian principalities, Qutaiba ibn Muslim, Umayyad governor of Greater Khorasan, launches a pacification campaign into Sogdiana which delivers him and Islam a wave of submissive acknowledgements. Samarkand is occupied by Arab troops and Ghurak is temporarily driven out.

720 :

Dewashtich of Penjikent, along with Karzanj, ruler of Paikand, are mentioned as leaders of an anti-Islam rebellion in Sogdiana. Together they liberate Samarkand, holding it in the face of relatively weak attempts to regain it. Said Abd al-Aziz ibn al-Hakam, Umayyad governor of Greater Khorasan, is removed from office for his failure to regain the city.

722 :

Dewashtich of Penjikent has a famous last stand against Islam from his mountain fortress of Mugh. That marks the beginning of the formal accession of Transoxiana into the Islamic empire, and soon results in the increasing Islamic control of the eastern regions as well. Among other things, this causes the break-up of the Sogdian commercial network, and ultimately an integration of Sogdiana into the empire.

729 - 731 :

The ikhshid of northern Ferghana aids his Türgish overlords at the siege of Kamarja. Two years later the Türgish are aided again from Ferghana during the Battle of the Defile (which allows Ḡūrak to recover control over Samarkand). The Türgish leader, Sulu of the Western Göktürks, enjoys over a decade of success in his battles against the Umayyads until he is murdered in 737/738, ending any remaining vestige of western Göktürk power.

731 - 737/8 :

Gurak / Ghurak / Ughrak : Restored on a semi-independent basis. Died.

737/8 - ? :

Turgar / Tu-ho : Ruler of Samarkand. 'King of Sogdia'.

747 - 749 :

The Abbasids under Abu Muslim begin an open revolt in Greater Khorasan against Umayyad rule. They are supported by the vassal states of Sogdiana, and notably by Qutayba of Bukhara. Khorasan quickly falls under their command and an army is sent westwards. Kufa falls in 749 and in November the same year Abu al-Abbas is recognised as caliph.

Sogdian records seem to fade away from around this time. Even the names of the rulers of Bukhara - one of the biggest cities - are unknown from the fourth quarter of the century onwards.

775 - 785 :

The Abbasids under Muhammad al Mahdi record several minor rulers across Transoxiana who pay nominal submission to the caliph. In effect they remain independent but largely careful not to annoy their distant overlords. The unnamed afshin of Ustrushana is mentioned as one of these rulers.

c.800 - 821 :

The region is gradually absorbed into the Islamic empire as it takes Persia. Governors, or emirs, are appointed to control the Islamic emirate of Khorasan in the name of the caliph. A seemingly partial occupation of Transoxiana by Tang dynasty China is effected in 659, but is ended in 665. Previously independent Ferghana gains a Samanid governor in 819, ending its independent existence.

Samanid

Emirate (Samarkand) :

The Samanids (or, more correctly, Sâmânids) took the Transoxiana region from the Tahirid governors of Khorasan in 820. From there they controlled the trade between Central Asia and the central Islamic caliphate, and these included the trade in Turkic slaves. The state grew to cover most of eastern Persia while the Buwayid amirs gained control of western Persia.

Their capital was the once-independent, post-Greek Sogdian city of Bukhara. The Persian tongue spoken by the Samanids gradually replaced the native Sogdian of the locals even while the region's strong traditions of mercantile independence were being supported. It was this Persian dialect that became today's Tajik language although some Sogdian dialects do survive, notably amongst the Yaghnobi Sogdians who fled Islamic control of the region to live in an isolated valley. Sogdian religions gradually vanished too, despite centuries of use of even the latest of them - Nestorian Christianity - while Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Manichaeism were also fading across all of the now-Islamic lands to the east of Iran.

It was the Samanid lands of eastern Khorasan that were by far the chief supplier of dirhams (Islamic silver coins) to the lands of northern and Eastern Europe during the Viking period in the ninth and tenth centuries. Starting around AD 900 and continuing into the late tenth century, millions of these coins were carried north-westwards through the Pontic-Caspian steppe by Muslim merchant caravans from Samanid cities and mints. Initially this was via the dominant Khazars of the Pontic steppe and then Rus merchants. After about 965, it was via the Rus themselves (Swedish Vikings and native Slavs who combined to form the grand principality of Kiev and several other small Slav states around this time). The Rus were were forced out of the lower Volga by the Volga Bulgars around 980, with them taking over ownership of regional trade. From Volga Bulgaria, most of these coins were subsequently exchanged in commercial transactions and were re-exported further west or north-west by Rus merchants, and then even further west into the Baltic basin and beyond.

(Additional information from Viking-Rus Mercenaries in the Byzantine-Arab Wars of the 950s-960s: the Numismatic Evidence, Roman K Kovalev, and from Global Security Watch: Central Asia, Reuel R Hanks (Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford, 2010).)

819 - 851 :

Saman Khoda

819 :

Previously independent Ferghana gains a Samanid governor in the form of Ahmad ibn Asad, ending its independent existence. The appointment is made by the Abbasid governor of Greater Khorasan.

821 :

The eastern province which includes Persia and Khorasan has lost Transoxiana to the Samanids, so Caliph al-Mamun appoints Tahir ibn al-Hussein, the successful commander of the campaign which had defeated the caliph's main rival (al Amin), as the new governor, beginning the Tahirid period of rule in the east. Tahir effectively declares independence in 822 in his new domains by failing to mention the caliph during a sermon at Friday prayers.

828 - 839 :

While in office as the Tahrid governor of Khorasan, Abdullah ibn Tahir ibn al-Hussein takes steps between 828-830 to improve the strength of the Samanids, his vassals in Transoxiana. In his role as governor of the east, Abdullah also claims Tabaristan as a dependency and insists that the tribute owed by Ispahbad Mazyar ibn Qarin, a recent convert to Islam, to the caliph should pass through him. Mazyar disagrees, planning to expand his domains, but in 839 he is captured and executed, securing Tahirid control over Tabaristan. This effectively ends the career of Afshin Ḥaydar ibn Kāwūs of Ustrushana as a supporter of Mazyar.

851 - 864 :

Ahmad ibn Asad : Former governor of Ferghana.

864 - 892 :

Nasr I

865 - 873 :

Having already secured his capital of Zaranj at the heart of his small kingdom, the Saffarid leader, Yaghub, expands eastwards to capture al-Rukhkhadj and Zamindawar followed by Zunbil and Kabul by 865. Some of his conquests even further east, towards Balk, encompass non- Islamic tribal chiefdoms. Harev (Herat) is taken in 870. Then he expands his borders greatly in 873 by ousting Emir Muhammad of the Tahirids. Khorasan is captured, giving the Saffarids a great swathe of new territory which may also include cities such as Ustrushana to the north of Samarkand.

892 - 907 :

Ismail I

900 :

The Saffarid emirs in formerly Tahirid-controlled Khorasan are defeated by the Samanids and reduced in territory to Seistan in Persia, where they remain Samanid vassals. The Samanids install their own governors in the Khorasan region, as well as in recently-captured Bukhara and Ustrushana (both taken in the 890s).

Two sides of a typical Abbasid-era coin, with this one being nineteen millimetres in diameter issued in Samarkand, which was soon taken by the Samanids 907 - 914 :

Ahmad II

914 - 943 :

As-Sa'id Nasr II

943 - 954 :

Hamid Nuh I

954 - 961 :

Abdül-Malik I

961 - 976 :

Mansur I

962 :

Zabulistan is seized by a rebellious Samanid governor and a semi-independent Afghan kingdom is formed with its capital at Ghazni. Although the rebel, Alptigin, establishes his independent rule of Ghazni, coins from the era show that he nominally acknowledges Samanid overlordship, always a useful ruse for avoiding an attack by former masters.

976 - 997 :

Nuh II

977 :

The Afghan city of Ghazni comes under the rule of the Yamanid dynasty, which becomes fully independent of Samanid control as it forms its own Ghaznavid sultanate, although it still pays lip service to its former masters.

994 :

Nuh II faces internal uprisings, as the emirate becomes more unstable, and the Ghaznavid ruler comes to his assistance. The rebels are defeated at Balkh and then Nishapur.

995 :

Usually under the influence of Persia, if not its direct control, the emirate of Khwarazm is initially centred on Samarkand and Bukhara. At its height, it extended to encompass almost all of modern Iran (except the western border area), eastern Azerbaijan, modern western Afghanistan, all of Turkmenistan, most of Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, and the southern areas of Kazakhstan.

997 - 999 :

Mansur II : Deposed.

997 :

Mahmud of Khwarazm campaigns against the Qara-Khitaï in Central Asia, but is ultimately defeated. His failure is a harbinger of problems to come where the Qara-Khitaï are concerned.

999 :

The Turkic Karakhanids depose Mansur II, allied with the Buwayids who are supreme in south-western Persia and Mesopotamia. The Karakhanids take possession of areas of Southern Khorasan.

999 - 1000 :

Abdül Malik II

1000 :

Samanid power swiftly declines in the face of Buwayid supremacy, while the revolt of the Ghaznavids brings the emirate to an end.

1000 - 1005 :

Ismail II al-Muntasir : Assassinated.

1005 :