| HURRIAN STATE OF URKESH & NAWAR (NAGAR) FeatureThe Hurrians (or Khurrites) were neither Semitics nor Indo-Europeans, but their origins are obscure. They appear to have emerged between 2500-2000 BC, probably from the Caucuses mountains to the north, to occupy the upper Tigris Valley and the upper Euphrates (close to the Assyrians), which had previously been the centre of the Chalcolithic Halaf culture. The end of the Akkadian empire enabled them to gain control of regions of northern Mesopotamia towards the end of the third millennium BC.

FeatureThey were able to found a small, somewhat nebulous state in Urkesh (modern Tell Mozan in Syria), in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, and in Nawar (or Nagar, now Tell Brak in Syria) in the northern Khabur Valley, and another in Arrapha. Urkesh seems to have been inhabited since around 5000 BC, as confirmed by archaeological discoveries of human remains there, and an urban settlement was founded around 2900 BC. Its founders were previously unknown, but finds from the Urkesh archaeology site at Tell Mozan have shown that the Hurrians were there by this stage (identified by their unique language). Perhaps they had always been there, in which case they were probably aboriginals - people who had been there for many thousands of years, pre-dating any emergence of civilisation. The heartland of the subsequent Hurrian settlement area, it was only in Urkesh, Nawar, and Arrapha that the Hurrians had a majority population, but settlements of Hurrians could be found spread across much of northern Mesopotamia. They also later migrated southwards into Babylonia, and westwards into Hatti and Kizzuwatna in Anatolia.

FeatureOnce in Anatolia, they may have been influenced by the Indo-European Luwians or Hittites, as the storm god Teshub was patronised by them. Luwians chiefly worshipped Teshub - 'Tarhun' in their language - but this was rendered as 'Tarhunta' in theophoric names. Teshub or Tarhun stands out as being another contraction of 'tu arun', meaning 'your protector'. Other pronunciations of this Asura god are Varuna, Ouranos, Taranis and, of course, the Germanic contracted form of Thor. This presence of an Asura in an Anatolian branch of Indo-Europeans (IEs) is intriguing. Either the cult was borrowed (from the Hurrians perhaps?), or the god is so old that it dates back to a time in which all branches of IEs were in contact with one another - ie. somewhere around a date of 4000-4500 BC at the latest. (A detailed examination of IE gods and origins can be found in connection with early Germanic groups in Scandinavia.)

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from Historical Atlas of the Ancient World, 4,000,000 to 500 BC, John Haywood (Barnes & Noble, 2000), from The Ancient Near East, c.3000-330 BC, Amélie Kuhrt (Volumes I & II, Routledge, 2000), from The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History, Colon McEvedy (which misses the period 1600-1300 BC but shows a Mitanni kingdom in 1300-1000 BC, by which time it had certainly disappeared - Penguin Books, 1967, revised 2002), from Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, Michael Road (Facts on File, 2000), from Ancient Iraq, Georges Roux (Penguin Books, 1992), from The Hurrians, Gernot Wilhelm (Aris & Philips Warminster 1989), from Naming Names: The 2004 Season of Excavations at Ancient Urkesh, Giorgio & Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati (via the Institute of Archaeology, UCLA), from A History of the Ancient Near East c.3000-323 BC, Marc van der Mieroop (Blackwell Publishing, 2004, 2007), and from External Links: The Rediscovery of Urkesh: Forgotten City of the Hurrians (Ancient Origins), and LA Archaeologists Digging in Syria Find City of Myth (Los Angeles Times, 1995), and Celebrating Life in Mesopotamia, Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati.)

? BC :

Kumarbi : Central god of the Hurrians. Ancestor king?

c.2300? BC :

Far from being recently arrived as has long been the prevailing theory, the Hurrians may have been here all along. Despite that, and despite being the likely founders of the city of Urkesh around 2900 BC, they only now seem to found the small state (or states) of Urkesh and Nawar, based on the two cities of the same name in northern Mesopotamia.

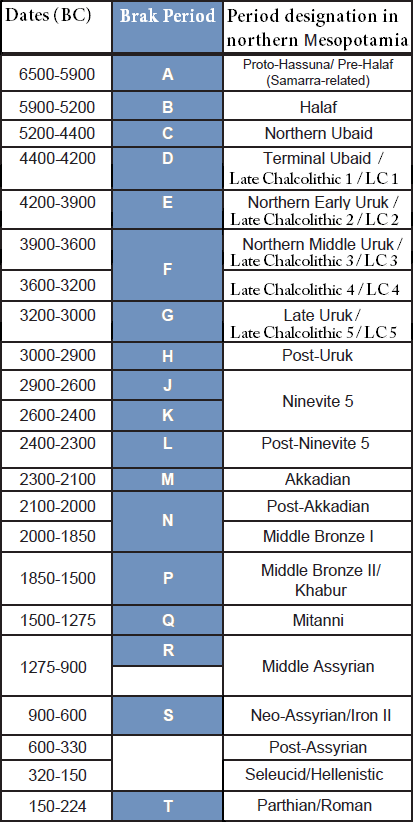

This fragment of Early Bronze Age pottery was produced in Mesopotamia around 3000 BC, as the early city-building movement there began to accelerate towards large-scale city states and a recorded history Nawar seems to fall under the dominance of the Akkadian empire for a period (cultural rather than military), with the city serving as an administrative centre. Despite this is it not conquered, perhaps the only such city not to be. Instead it is a willing ally. The names of five of the kings of Urkesh and Nawar are known for this period, but there are certainly others whose names have been lost. Uniquely, the people of Urkesh use the term 'endan' to refer to the early kings.

fl c.2250 BC :

Tupkish : Endan of Urkesh. Founded the royal palace.

fl c.2250 BC :

Uqnitum : Wife and queen.

c.2225 BC :

Akkadian influence becomes noticeable in Urkesh around this time, perhaps due to the regional dominance of Akkad and the partnership that is formed between this empire and Urkesh. Tupkish and his wife, Uqnitum, build a great palace in the city which is being excavated by archaeologists into the twenty-first century AD. They are portrayed as a powerful, united royal family with a crown prince who is fully expected to succeed them.

Urkesh forms an important stop both on the north-south trade route between Anatolia and the cities of Syria and Mesopotamia, and the east-west route which links the Mediterranean with the Zagros Mountains of western Iran. Urkesh also controls the highlands immediately to the north of the city where extensive supplies of copper are located, which is what makes the city wealthy.

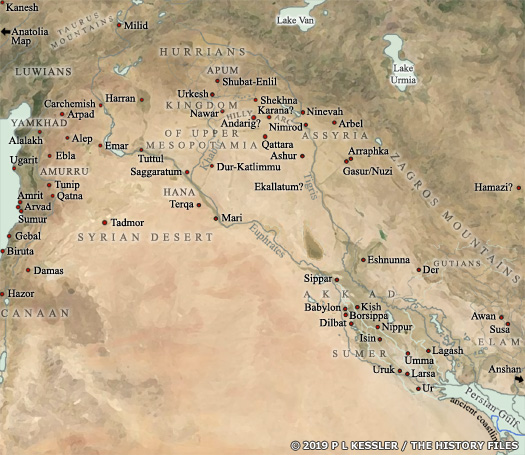

This general map of Mesopotamia and its neighbouring territories roughly covers the period between 2000-1600 BC. It reveals the concentration of city states in Sumer, in the south fl c.2225? BC? :

? : Son? Endan of Urkesh. Name unknown. Succeed Tupkish.

c.2225 BC :

Tar'am-Agade,

the daughter of Naram-Sin, king of Akkad, marries a king of Urkesh.

For quite some time it had been thought this may be Tupkish (above),

but the discovery in 1995 of clay seal imprints mentioning the previously-unknown

Queen Uqnitum show that she rules strongly beside him as part of

an equal (or near equal) partnership. Naram-Sin's daughter may instead

marry his successor whose name is not known.

Ishar-Kinum : Endan of Urkesh. Reigned after the successor of Tupkish.

fl c.2200 BC :

Ishar-Kinum's name is only rediscovered by archaeologists in 2004, from a freshly uncovered seal inscription. The findings from the royal palace remains at Tell Mozan in what is now north-eastern Syria continue to expand the otherwise limited knowledge about Urkesh and Newar and their rulers.

fl c.2000s BC :

Tish-atal / Tih-Atal : Endan of Urkesh. The last endan?

Although no firm date can be ascribed to the rule of Tish-atal (Tishatal, or the now outdated Tishari), he is contemporary with Ur's Third Dynasty to the far south of Urkesh. This places him between about 2112-2004 BC. The first source for him to be found in excavations at Tell Mozan is a cuneiform inscription about a temple of Nergal.

Curiously, there may be no further endans after him. The only other rulers of Urkesh are titled lugal, the Sumerian term for a ruler. Does Sumerian influence gain ascendancy over native Hurrian practices around this time, just as Sumer itself is fading? To balance this, Tupkish has also been referred to as lugal as well as endan, so perhaps the change is simply down to trends in scholarly language.

Gypsum lion head finial, possibly from the throne of a votive statue of Early Dynastic III at Sippar, about 2500 BC. The Sumerian word for 'king' ('lugal') is inscribed on one side Shatar-mat (Sa-dar-wa!(ŠI)-at?) : Lugal of Urkesh.

The

name Sa-dar-wa!(ŠI)-at is known from the seal of Puššam.

While it may be that of a trader, Konrad Volk's examination of the

seal has produced a degree of likelihood that a ruler is mentioned

instead.

Atal-šen / Atal-shen : Son. Lugal of Urkesh & Nawar.

fl c.2050 BC :

Ann-atal : Lugal of Urkesh.

c.2000 BC :

Hurrians found the small state of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk) in northern Mesopotamia at around the same time as they adopt Akkadian cuneiform script for their own language. This would appear to be an eastwards expansion of Hurrians into the territory of the early Assyrians.

c.1850 - 1809 BC :

The new Amorite rulers of Mari subdue Urkesh, making it a vassal state. However, the locals do not submit easily, and letters sent back to Mari attest to a strong sense of resistance against foreign rule. Such a reversal of fortune seems to suggest that Urkesh has passed its peak of influence and wealth in the past century or so.

The large royal palace at Urkesh, discovered in the 1980s and still being excavated in 2010, yielded written evidence which allowed it to be identified as the lost palace and city fl c.1850 BC :

Te'irru / Terru : Amorite vassal king of Mari.

c.1809 - 1761 BC :

Urkesh is made a vassal of the kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia. In all likelihood, with the collapse of this personal empire from about 1776 BC, Mari renews its control of Urkesh until its own fall. Does Urkesh re-establish its own independent kingship afterwards? Unfortunately nothing is known of this period, despite a Hurrian king who is mentioned in the Old Testament (below). What is known is that Hurrians begin migrating westwards in this period, where they can be found in cities such as Alakhtum. That could be due to Mari allowing its citizens to move freely within its territory, but it is more likely due to Mari's fall at the hands of Babylon around 1761 BC and a sudden lack of regional opposition to Hurrian migration.

fl c.1750 BC :

Ariukki : A Hurrian king, but city unknown. King Arioh of the Bible.

c.1650 BC :

Hurrians invade the Old Hittite empire several times and campaign southwards, perhaps pushing refugees from Syria and the Levant into Egypt where they form the Hyksos peoples.

c.1600 BC :

The

region is fought over by Yamkhad and the Hittites, But following

the collapse of Yamkhad and the decline of the Hittites shortly

afterwards, Hurrian migrations into Syria and Anatolia increase.

The latter sees them form a state around the coastal region of the

'land of Adaniya' (modern Adana) near the coast during the dark

age of this period. With a general population that is likely to

be Luwian for the most part, this state becomes known as Kizzuwatna.

c.1530 BC :

Following the collapse of Babylonian regional power, the Hurrian state of Mitanni emerges as a major power which entirely dominates the region. With true Hurrian power now lying elsewhere, Urkesh is abandoned around this time to gradually be swallowed by the sand and forgotten by history. Some areas of it remain inhabited for a time, but amid a changing and seemingly declining landscape. This is one of substantial collapses (in terms of brickfall) and reuse, especially with the former royal wing of the palace being used on a different floor plan.

Mitanni warriors are shown here dressed in a typical northern Mesopotamian costume which they most likely picked up following their arrival in the region in the 1600s BC In the AD 1980s archaeologists discover Tell Mozan, a towering mound that hides the remains of an ancient palace, temple, and plaza. A decade later researchers reach the exciting realisation that Tell Mozan is the lost city of Urkesh. Excavations continue into the twenty-first century until the Syrian Civil War provides a lengthy interruption.

Tell Brak (Nagar, Nawar) :

Nagar Shown in Red Dots

Tell Brak as seen from a distance with several excavation areas visible Alternative name : Nagar, Nawar

Location : Al-Hasakah Governorate, Syria

Coordinates : 36°40'03.42 N 41°03'31.12 E

Type : Settlement

Area : 40 hectares (99 acres).

Height : 40 metres (130 ft).

History :

Periods : Neolithic, Bronze Age

Cultures : Halaf culture, Northern Ubaid, Uruk, Kish civilization, Hurrian

Site notes :

Excavation dates : 1937–1938, 1976–2011

Archaeologists : Max Mallowan, David Oates, Joan Oates

Public access : yes

Tell Brak (Nagar, Nawar) was an ancient city in Syria; its remains constitute a tell located in the Upper Khabur region, near the modern village of Tell Brak, 50 kilometers north-east of Al-Hasaka city, Al-Hasakah Governorate. The city's original name is unknown. During the second half of the third millennium BC, the city was known as Nagar and later on, Nawar.

Starting as a small settlement in the seventh millennium BC, Tell Brak evolved during the fourth millennium BC into one of the biggest cities in Upper Mesopotamia, and interacted with the cultures of southern Mesopotamia. The city shrank in size at the beginning of the third millennium BC with the end of Uruk period, before expanding again around c. 2600 BC, when it became known as Nagar, and was the capital of a regional kingdom that controlled the Khabur river valley. Nagar was destroyed around c. 2300 BC, and came under the rule of the Akkadian Empire, followed by a period of independence as a Hurrian city-state, before contracting at the beginning of the second millennium BC. Nagar prospered again by the 19th century BC, and came under the rule of different regional powers. In c. 1500 BC, Tell Brak was a center of Mitanni before being destroyed by Assyria c. 1300 BC. The city never regained its former importance, remaining as a small settlement, and abandoned at some points of its history, until disappearing from records during the early Abbasid era.

Different peoples inhabited the city, including the Halafians, Semites and the Hurrians. Tell Brak was a religious center from its earliest periods; its famous Eye Temple is unique in the Fertile Crescent, and its main deity, Belet Nagar, was revered in the entire Khabur region, making the city a pilgrimage site. The culture of Tell Brak was defined by the different civilizations that inhabited it, and it was famous for its glyptic style, equids and glass. When independent, the city was ruled by a local assembly or by a monarch. Tell Brak was a trade center due to its location between Anatolia, the Levant and southern Mesopotamia. It was excavated by Max Mallowan in 1937, then regularly by different teams between 1979 and 2011, when the work stopped due to the Syrian Civil War.

Name

:

During the third millennium BC, the city was known as "Nagar", which might be of Semitic origin and mean a "cultivated place". The name "Nagar" ceased occurring following the Old Babylonian period, however, the city continued to exist as Nawar, under the control of Hurrian state of Mitanni. Hurrian kings of Urkesh took the title "King of Urkesh and Nawar" in the third millennium BC; although there is general view that the third millennium BC Nawar is identical with Nagar, some scholars, such as Jesper Eidem, doubt this. Those scholars opt for a city closer to Urkesh which was also called Nawala/Nabula as the intended Nawar.

History :

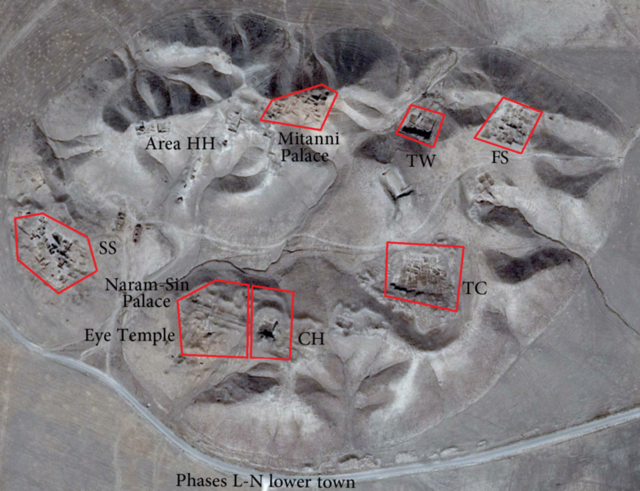

Tell Brak's periods

Early settlement :

The first city :

Eye figurines from the Eye Temple In southern Mesopotamia, the original Ubaid culture evolved into the Uruk period. The people of the southern Uruk period used military and commercial means to expand the civilization. In Northern Mesopotamia, the post Ubaid period is designated Late Chalcolithic / Northern Uruk period, during which, Tell Brak started to expand.

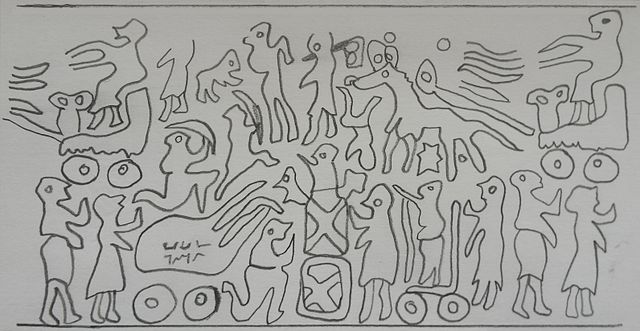

Period Brak E witnessed the building of the city's walls, and Tell Brak expansion beyond the mound to form a lower town. By the late 5th millennium BC, Tell Brak reached the size of c. 55 hectares. Area TW of the tell (Archaeologists divided Tell Brak into areas designated with Alphabetic letters. See the map for Tell Brak's areas) revealed the remains of a monumental building with two meters thick walls and a basalt threshold. In front of the building, a sherd paved street was discovered, leading to the northern entrance of the city.

The city continued to expand during period F, and reached the size of 130 hectares. Four mass graves dating to c. 3800–3600 BC were discovered in the submound, Tell Majnuna, north of the main tell, and they suggest that the process of urbanization was accompanied by internal social stress, and an increase in the organization of warfare. The first half of period F (designated LC3), saw the erection of the Eye Temple, which was named for the thousands of small alabaster "Eye idols" figurines discovered in it. Those idols were also found in area TW.

Interactions with the Mesopotamian south grew during the second half of period F (designated LC4) c. 3600 BC, and an Urukean colony was established in the city. With the end of Uruk culture c 3000 BC, Tell Brak's Urukean colony was abandoned and deliberately leveled by its occupants. Tell Brak contracted during the following periods H and J, and became limited to the mound. Evidence exists for an interaction with the Mesopotamian south during period H, represented by the existence of materials similar to the ones produced during the southern Jemdet Nasr period. The city remained a small settlement during the Ninevite 5 period, with a small temple and associated sealing activities.

Kingdom of Nagar :

The kingdom of Nagar c. 2340 BC Nagar

c. 2600 BC – c. 2300 BC

Capital : Nagar

Common languages : Nagarite

Religion : Mesopotamian

Government : Monarchy

Historical era :

Bronze Age :

• Established c. 2600 BC

• Disestablished c. 2300 BC

Around c. 2600 BC, a large administrative building was built and the city expanded out of the tell again. The revival is connected with the Kish civilization, and the city was named "Nagar". Amongst the important buildings dated to the kingdom, is an administrative building or temple named the "Brak Oval", located in area TC. The building have a curved exterior wall reminiscent of the Khafajah "Oval Temple" in central Mesopotamia. However, aside from the wall, the comparison between the two buildings in terms of architecture is difficult, as each building follows a different plan.

The oldest references to Nagar comes from Mari and tablets discovered at Nabada. However, the most important source on Nagar come from the archives of Ebla. Most of the texts record the ruler of Nagar using his title "En", without mentioning a name. However a text from Ebla mentions Mara-Il, a king of Nagar; thus, he is the only ruler known by name for pre-Akkadian Nagar and ruled a little more than a generation before the kingdom's destruction.

At its height, Nagar encompassed most of the southwestern half of the Khabur Basin, and was a diplomatic and political equal of the Eblaite and Mariote states. The kingdom included at least 17 subordinate cities, such as Hazna, and most importantly Nabada, which was a city-state annexed by Nagar, and served as a provincial capital. Nagar was involved in the wide diplomatic network of Ebla, and the relations between the two kingdoms involved both confrontations and alliances. A text from Ebla mention a victory of Ebla's king (perhaps Irkab-Damu) over Nagar. However, a few years later, a treaty was concluded, and the relations progressed toward a dynastic marriage between princess Tagrish-Damu of Ebla, and prince Ultum-Huhu, Nagar's monarch's son.

Nagar was defeated by Mari in year seven of the Eblaite vizier Ibrium's term, causing the blockage of trade routes between Ebla and southern Mesopotamia via upper Mesopotamia. Later, Ebla's king Isar-Damu concluded an alliance with Nagar and Kish against Mari, and the campaign was headed by the Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish, who led the combined armies to victory in a battle near Terqa. Afterwards, the alliance attacked the rebellious Eblaite vassal city of Armi. Ebla was destroyed approximately three years after Terqa's battle, and soon after, Nagar followed in c. 2300 BC. Large parts of the city were burned, an act attributed either to Mari, or Sargon of Akkad.

Akkadian period :

Palace of Naram-Sin Following its destruction, Nagar was rebuilt by the Akkadian empire, to form a center of the provincial administration. The city included the whole tell and a lower town at the southern edge of the mound. Two public buildings were built during the early Akkadian periods, one complex in area SS, and another in area FS. The building of area FS included its own temple and might have served as a caravanserai, being located near the northern gate of the city. The early Akkadian monarchs were occupied with internal conflicts, and Tell Brak was temporarily abandoned by Akkad at some point preceding the reign of Naram-Sin. The abandonment might be connected with an environmental event, that caused the desertification of the region.

The destruction of Nagar's kingdom created a power vacuum in the Upper Khabur. The Hurrians, formerly concentrated in Urkesh, took advantage of the situation to control the region as early as Sargon's latter years. Tell Brak was known as "Nawar" for the Hurrians, and kings of Urkesh took the title "King of Urkesh and Nawar", first attested in the seal of Urkesh's king Atal-Shen.

The use of the title continued during the reigns of Atal-Shen's successors, Tupkish and Tish-Atal, who ruled only in Urkesh. The Akkadians under Naram-Sin incorporated Nagar firmly into their empire. The most important Akkadian building in the city is called the "Palace of Naram-Sin", which had parts of it built over the original Eye Temple. Despite its name, the palace is closer to a fortress, as it was more of a fortified depot for the storage of collected tribute rather than a residential seat. The palace was burned during Naram-Sin's reign, perhaps by a Lullubi attack, and the city was burned toward the end of the Akkadian period c. 2193 BC, probably by the Gutians.

Post-Akkadian

kingdom :

Foreign rule and later periods :

The Mitannian palace During period P, Nagar was densely populated in the northern ridge of the tell. The city came under the rule of Mari, and was the site of a decisive victory won by Yahdun-Lim of Mari over Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria. Nagar lost its importance and came under the rule of Kahat in the 18th century BC.

During period Q, Tell Brak was an important trade city in the Mitanni state. A two-story palace was built c. 1500 BC in the northern section of the tell, in addition to an associated temple. However, the rest of the tell was not occupied, and a lower town extended to the north but is now all but destroyed through modern agriculture. Two Mitannian legal documents, bearing the names of kings Artashumara and Tushratta, were recovered from the city, which was destroyed between c.1300 and 1275 BC, in two waves, first at the hands of the Assyrian king Adad-Nirari I, then by his successor Shalmaneser I.

Little evidence of an occupation on the tell exists following the destruction of the Mitannian city, however, a series of small villages existed in the lower town during the Assyrian periods. The remains of a Hellenistic settlement were discovered on a nearby satellite tell, to the northwestern edge of the main tell. However, excavations recovered no ceramics of the Parthian-Roman or Byzantine-Sasanian periods, although sherds dating to those periods are noted. In the middle of the first millennium AD, a fortified building was erected in the northeastern lower town. The building was dated by Antoine Poidebard to the Justinian era (sixth century AD), on the basis of its architecture. The last occupation period of the site was during the early Abbasid Caliphate's period, when a canal was built to provide the town with water from the nearby Jaghjagh River.

Society

:

No Hurrian names are recorded in the pre-Akkadian period, although the name of prince Ultum-Huhu is difficult to understand as Semitic. During the Akkadian period, both Semitic and Hurrian names were recorded, as the Hurrians appear to have taken advantage of the power vacuum caused by the destruction of the pre-Akkadian kingdom, in order to migrate and expand in the region. The post-Akkadian period Tell Brak had a strong Hurrian element, and Hurrian named rulers, although the region was also inhabited by Amorite tribes. A number of the Amorite Banu-Yamina tribes settled the surroundings of Tell Brak during the reign of Zimri-Lim of Mari, and each group used its own language (Hurrian and Amorite languages). Tell Brak was a center of the Hurrian-Mitannian empire, which had Hurrian as its official language. However, Akkadian was the region's international language, evidenced by the post-Akkadian and Mitannian eras tablets, discovered at Tell Brak and written in Akkadian.

Religion

:

During the pre-Akkadian kingdom's era, Hazna, an old cultic center of northern Syria, served as a pilgrimage center for Nagar. The Eye Temple remained in use, but as a small shrine, while the goddess Belet Nagar became the kingdom's paramount deity. The temple of Belet Nagar is not identified but probably lies beneath the Mitannian palace. The Eblaite deity Kura was also venerated in Nagar, and the monarchs are attested visiting the temple of the Semitic deity Dagon in Tuttul. During the Akkadian period, the temple in area FS was dedicated to the Sumerian god Shakkan, the patron of animals and countrysides. Tell Brak was an important religious Hurrian center, and the temple of Belet Nagar retained its cultic importance in the entire region until the early second millennium BC.

Culture :

Area TW Northern Mesopotamia evolved independently from the south during the Late Chalcolithic / early and middle Northern Uruk (4000–3500 BC). This period was characterized by a strong emphasis on holy sites, among which, the Eye Temple was the most important in Tell Brak. The building containing "Eyes" idols in area TW was wood paneled, whose main room had been lined with wooden panels. The building also contained the earliest known semi columned facade, which is a character that will be associated with temples in later periods.

By late Northern Uruk and especially after 3200 BC, northern Mesopotamia came under the full cultural dominance of the southern Uruk culture, which affected Tell . Brak's architecture and administration. The southern influence is most obvious in the level named the "Latest Jemdet Nasr" of the Eye Temple, which had southern elements such as cone mosaics. The Uruk presence was peaceful as it is first noted in the context of feasting; commercial deals during that period were traditionally ratified through feasting. The excavations in area TW revealed feasting to be an important local habit, as two cooking facilities, large amounts of grains, skeletons of animals, a domed backing oven and barbequing fire pits were discovered. Among the late Uruk materials found at Tell Brak, is a standard text for educated scribes (the "Standard Professions" text), part of the standardized education taught in the 3rd millennium BC over a wide area of Syria and Mesopotamia.

A drawing of a seal from Nabada, pre-Akkadian kingdom of Nagar, in "Brak Style" The pre-Akkadian kingdom was famed for its acrobats, who were in demand in Ebla and trained local Eblaite entertainers. The kingdom also had its own local glyptic style called the "Brak Style", which was distinct from the southern sealing variants, employing soft circled shapes and sharpened edges. The Akkadian administration had little effect on the local administrative traditions and sealing style, and Akkadian seals existed side by side with the local variant. The Hurrians employed the Akkadian style in their seals, and Elamite seals were discovered, indicating an interaction with the western Iranian Plateau. Tell Brak provided great knowledge on the culture of Mitanni, which produced glass using sophisticated techniques, that resulted in different varieties of multicolored and decorated shapes. Samples of the elaborate Nuzi ware were discovered, in addition to seals that combine distinctive Mitannian elements with the international motifs of that period.

Wagons

:

Government

:

Rulers of Tell Brak :

Economy

:

Trade was also an important economic activity for the pre-Akkadian kingdom of Nagar, which had Ebla and Kish as major partners. The kingdom produced glass, wool, and was famous for breeding and trading in the Kunga, a hybrid of a donkey and a female onager. Tell Brak remained an important commercial center during the Akkadian period, and was one of Mitanni's main trade cities. Many objects were manufactured in Mitannian Tell Brak, including furniture made of ivory, wood and bronze, in addition to glass. The city provided evidence for the international commercial contacts of Mitanni, including Egyptian, Hittite and Mycenaean objects, some of which were produced in the region to satisfy the local taste.

Equids

:

Site

:

Tell Brak's landmarks Tell Brak was excavated by the British archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan, husband of Agatha Christie, in 1937 and 1938. The artifacts from Mallowan's excavations are now preserved in the Ashmolean Museum, National Museum of Aleppo and the British Museum's collection; the latter contain the Tell Brak Head dating to c. 3500–3300 BC.

A team from the Institute of Archaeology of the University of London, led by David and Joan Oates, worked in the tell for 14 seasons between 1976 and 1993. After 1993, excavations were conducted by a number of field directors under the general guidance of David (until 2004) and Joan Oates. Those directors included Roger Matthews (in 1994–1996), for the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research of the University of Cambridge; Geoff Emberling (in 1998–2002) and Helen McDonald (in 2000–2004), for the British Institute for the Study of Iraq and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2006, Augusta McMahon became field director, also sponsored by the British Institute for the Study of Iraq. A regional archaeological field survey in a 20 km (12 mi) radius around Brak was supervised by Henry T. Wright (in 2002–2005). Many of the finds from the excavations at Tell Brak are on display in the Deir ez-Zor Museum. The most recent excavations took place in the spring of 2011, but archaeological work is currently suspended due to the ongoing Syrian Civil War.

Syrian

Civil War :

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tell_Brak |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||