| CIMMERIANS Homer, writing in the ninth century BC, noted the existence of the Cimmerians (or Kimmerioi in Greek texts). Many other Classical writers in subsequent years also mentioned them, including Herodotus in the fifth century BC, but the subject of the Cimmerians is a complicated one. In terms of their origins they are generally associated with the Koban culture of the northern Caucuses, and then the subsequent Chernogorovka and Novocherkassk cultures of Ukraine and southern Russia. They burst onto the historical stage in the ninth and eight centuries BC, surprising the established civilisations of the Near East with their ability to defeat powerful city states. They conquered and looted until they were defeated themselves. After that they appear to have broken up into various groups, at least one of which may have settled in Tabal (Classical Cappadocia) in Anatolia, and others in Thrace. But that's just half the story.

Although the Cimmerians cannot specifically be located in any single location before their appearance in Anatolia, it is generally agreed that they originated in the Pontic-Caspian steppe (the steppe lands to the north of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea). This region had long been a breeding ground for pastoral horse-borne warrior groups, ever since the Yamnaya Horizon of the mid-fourth millennium BC saw the sudden expansion and migration of the Indo-European tribes. Herodotus provided a very clear perspective of the peoples whom he said lived to the north of the Black Sea, and he also placed the Cimmerians on the Pontic steppe. More specifically, though, it was suggested by Isaac Asimov in his massive historical work that 'Cimmerium', the homeland of the Cimmerians, gave rise to the Turkic toponym, Qirim. Through the spread of Turkic tribes into the Pontic-Caspian steppe after the sixth century AD arrival of the Göktürk empire, this became the basis of the name 'Crimea'. Whether this was the core of the Cimmerian homeland is doubtful, but it probably fell within their sphere of influence.

The Cimmerians have been linked to Celts and Thracians, based at least partially on ancient Greek sources. Indications are that the Cimmerians became associated with the Thracians around a large swathe of the western coast of the Black Sea, and eventually merged with them (following their final defeat and break-up). Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt stated that the language of the Cimmerians could have been a 'missing link' between Thracian and Iranian. Both of these were of Indo-European ancestry, so there was likely some basic similarities between the languages. The Cimmerians have also been associated with the Biblical Gomer or Gomerians. A quick check of Sanskrit reveals that the basic word for a cow is 'go'. This is the same in proto-Germanic. An educated guess would be that the tribal name Gomer is derived from a word for cattle, just as Boii is derived from a Celtic word for cows. Most Indo-European groups were great pastoralists.

The complications arise when considering the so-called 'Thraco-Cimmerian Hypothesis', a rather controversial subject to say the least. This concerns an Eastern Celtic 38 group, part of the Cimmerian-Scythian people, who blasted their way into the historical record in the eighth and seventh centuries BC, and eventually settled to a large extent amongst the Thracian tribes (just as the Cimmerians are supposed to have done). Some modern writers believe that a Thraco-Cimmerian migration westwards out of Thrace (or several, more probably) triggered cultural changes that contributed to the transformation of the Celts, from the Hallstatt C culture into the La Tène. In fact, although a specific Thraco-Cimmerian migration along the Danube is now less supported, it is undeniable that a Thraco-Cimmerian cultural influence did make its way westwards. These were Indo-European groups who at the very least shared the same cultural values, and martial equipment - and probably language too - as the Thracians and Cimmerians, and even Scythians.

Tying archaeological evidence to the Thraco-Cimmerian hypothesis can sometimes be dismissed by scholars (although not all of them). When studying the hypothesis, Anne Kristiansen has focussed on a shift in production centres from Hungary to Italy and the Alpine region. The weight of evidence shows that there was a warrior culture of the horse/wagon complex in the eighth century BC (such horse and wagon peoples were typical of Pontic-Caspian steppe cultures, and they persisted in the region for a surprisingly long time). From a Central European perspective, this particular culture followed the Danube to the Hallstatt regions of the east - Austria, and perhaps Bavaria, these being the eastern limits of the core Celtic homeland. In successive waves from the ninth to the sixth centuries BC they pushed further west before veering off to the north. Ultimately, one branch followed the course of the River Elbe and a second backtracked west from the headwaters of the Rhine, heading north-east to the Elbe and then north into Jutland (where it theoretically formed, or merged with the ancestors of, the Cimbri). The entire Hallstatt complex was altered with new male prestige weapons and specialised horse tack and wagons that were new to the region, and these were associated with new ruling elites, especially in eastern Central Europe. Kristiansen considers the influences to be not only Cimmerian but also Scythian (another nomadic horse-based group from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, some of whom ventured into the Transoxiana region of Central Asia to become better known as the Sakas).

David Rankin also supported this theme. He wrote of the evidence that Celtic peoples owed their origins to a specifically eastern warrior culture which imposed itself upon an Eastern European culture of the Urnfield or Lusatian type, and which introduced the lordly habit of tumulus burial. Specific Thraco-Cimmerian archaeological finds with the earliest known iron goods (along with bronze items), such as horse bridles have been documented in the Balkans, along the Danube corridor to Lake Zurich in Switzerland, and north to Denmark, dated between the tenth and eighth centuries BC. It is now recognised that some of the Thracian tribes may have been Celtic (or perhaps more probably proto-Celtic, sharing close similarities with groups in Austria and Bavaria). These incomers most likely brought typical Balkan haplogroups into the western Celtic areas, probably decreasing in numbers as a function of distance from their home base. The Bronze Age shift to the Iron Age was not altogether smooth and had regional features that delayed its introduction. Iron was in use in Greece by 1000 BC (after the Doric invasions there), but not until 750 BC did Central Europe see its introduction (with the Iron Age Hallstatt C Celts), and not until 500 BC did its use emerge in the Nordic zone (amongst the early Germanic groups). Changes were gradual rather than reflecting any sort of 'revolution'.

Among the Celts, their original name (which is proposed here as being Galat - see feature link, right) appears to survive best along the fringes of their expansion. A group would become isolated sufficiently on the borders so that they had no competitors who were using the same name, and therefore had no reason to change that name (see, for instance, Galatians, Caledonians, and Galicia). If the Cimmerian name followed this pattern then the Cimbri of Jutland may indeed be a Cimmerian/Celtic mix which retained their old name. Given the close Indo-European relationship between all of these groups that name could still have the original meaning of 'compatriots' or 'companions' that is normally ascribed to the Cimbri. This still would not invalidate the view of many modern scholars of them being a Germanic tribe with Celtic influences.

Furthermore, whilst the name of one of the most powerful Cimmerian leaders, the very Celtic-seeming Tugdamme, may be a borrowing between different, separated groups, it is far more likely to be a direct adoption from one group into another by conquest or consolidation. The idea that the emergence of the La Tène P-Celts was the result of Hallstatt Q-Celts being influenced or taken over by nomadic Cimmerians/Scythians or their associates is a very fascinating one. That something made a change in material culture and language amongst the Celts is not disputed, but what was it? The frustrating thing is that not enough is known about Cimmerian language to know whether they were using the same 'kw' sound as the Hallstatt Celts or whether they used the substituted 'p' sound of the La Tène Celts. If the latter then they may well have introduced this speech shift to the Celts, along with many other innovations.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry, David K Faux, from Asimov's Chronology of the World, Isaac Asimov, from Who were the Cimmerians, and where did they come from? Anne Katrine Gade Kristensen (Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, Hist-fil. Medd 57), from Celts and the Classical World, David Rankin (1996), from The Civilisation of the East, Fritz Hommel (Translated by J H Loewe, Elibron Classic Series, 2005), from Europe Before History, Kristian Kristiansen, from The History of Esarhaddon (Son of Sennacherib) King of Assyria, BC 681-688, Ernest A Budge, and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Britannica, and The Balts, Marija Gimbutas (1963, previously available online thanks to Gabriella at Vaidilute, but still available as a PDF - click or tap on link to download or access it), and Ancient Sinope: First Part, David M Robinson (The American Journal of Philology, Vol 27 No 2, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1906, and available from JSTOR).)

c.1200 - 900 BC :

The proto-Baltic sphere has become divided into several zones of influence during the Bronze Age. The western zone, covering eastern Poland, the former region of Prussia, and western parts of Lithuania and Latvia, is under the influence of the Central European metallurgical centre. In the eastern or continental zone, amid the forests which extend from eastern Lithuania and Latvia to the upper Volga basin, the people retain an archaic character, with these eastern Balts being in active contact with the Uralic-speaking Finno-Ugrians, Cimmerians, proto-Scythians, and early Slavs.

Decaying from late in the thirteenth century BC, the Hittite empire, and probably Tarhuntassa, are looted and destroyed by various surrounding peoples, including the Kaskans and Sea Peoples. Following the subsequent dark age, the Armenians occupy eastern Anatolia by the eighth century BC, although the region is often overrun by barbarian peoples from the Pontic-Caspian steppe such as the proto-Cimmerians.

It is during this period, nominally 1183-1173 BC, that Odysseus of Ithaca rounds off his part in the successful defeat of Troy by conducting a ten year voyage of discovery and adventure. Written down by Homer in the ninth century BC, the text mentions a people called the Kimmerior. They live beyond Oceanus (taken in this instance to mean the Black Sea), in a land of fog and darkness at the edge of the world and the entrance to Hades.

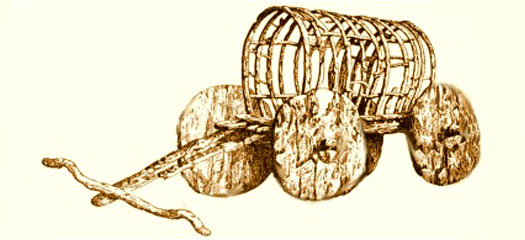

This primitive Yamnaya Horizon wagon was unearthed at Lchashen, on the western shore of Lake Sevan in modern Armenia in the South Caucuses, but the style would have been very similar in the North Caucuses and on the Pontic-Caspian steppe c.900 BC :

From around this date, rich, well-organised 'kingdoms' or 'chiefdoms'

develop in the Caucuses. They interact with civilisations to their

south, in Anatolia and Mesopotamia, usually by raiding into their

territory. Typical horse bits and cheek-pieces of an early Thraco-Cimmerian

type are found by archaeologists in the same region of the Caucuses.

The early Cimmerians here are generally associated with the Chernogorovka

and Novocherkassk cultures of Ukraine and southern Russia.

It is later in this century that the Cimmerians are pushed out of their homeland in the North Caucuses by the Scythians. The most probable reason is over-population and increasing border tensions between the two, but it is common for pastoral tribal groups to migrate when conditions become too cramped. Possibly the Scythians have jumped the gun and invaded Cimmerian territory before this can take place. Either way, the Cimmerians are forced to move on, some seemingly following the Black Sea coastline southwards until they meet the kingdom of Kolkis. Others would seem to head west from their Pontic homeland, circling the Black Sea until they make contact with Thracian tribes.

The Scythians acquire much of the Caucasian and Cimmerian cultural legacy and mix them with their own Ponto-Caucasian cultural elements. These oriental influences appreciably change the material culture of Central Europe. The Baltic and Germanic cultures in Northern Europe remain untouched by the Scythian incursions, but the new cultural elements reached them through continuous commercial relations with Central Europe, notably in relation to the Lusatian culture.

730s - 720s BC :

The kingdom of Kolkis is overrun by Cimmerians and Scythians, and it disintegrates. Whatever had taken place between Scythians and Cimmerians in the previous century to push the latter out of their homeland, the two seem to be acting in unison now.

It seems to be around this time that the window for the 'Thraco-Cimmerian Hypothesis' first opens. The Cimmerians and Scythians have suddenly positioned themselves as a more powerful collection of tribes which are not afraid of thundering around the Black Sea coast (on either side of the sea itself) and waging war against established kingdoms. It is known that Cimmerians later settle amongst the Thracian tribes, so to be that welcome they must share some common points of interest, such as language or culture.

The common points would seem to be old Urnfield traditions in metalwork mixed with new Cimmerian influences from the Caucuses. Could they already be mixing with Thracians in this period, with some groups beginning to explore further along the River Danube to enter regions that are controlled by the Celts of the Hallstatt C culture and also to influence the Illyrians on the western side of the Balkans? The weight of evidence shows that there is indeed a warrior culture of the horse/wagon complex in the eighth century BC and also a shift in production centres from Hungary to Italy and the Alpine region. This would match well with a Thraco-Cimmerian migration along the Danube (whether in person or by osmosis through neighbouring migratory groups).

In successive waves from the ninth to the sixth centuries BC these migrating warrior groups push west towards the headwaters of the Danube before veering off to the north. Ultimately, one branch follows the course of the River Elbe and a second backtracks west from the headwaters of the Rhine, heading north-east to the Elbe and then north into Jutland (where it theoretically forms, or merges with the ancestors of, the Cimbri).

Could the 'Thraco-Cimmerian'-driven or influenced migration along the Danube have brought with it the cultural changes that, around two hundred years later, resulted in the burial of the 'Celtic princess' at the Heuneburg, a centre of Celtic culture in south-western Germany 714 - 713 BC :

Much to the shock of Sargon of Assyria, while his main army is occupied

in the east, Ambaris of Tabal allies himself with Midas of Phrygia

and Rusa of Urartu (possibly immediately before the latter's suicide),

as well as the local Tabalean rulers in an attempt to invade Que.

Sargon reacts quickly, invading Tabal and capturing Ambaris, his

family and the nobles of his country, all of whom are taken to Assyria.

Tabal is annexed as an Assyrian province. Sargon is noted for using

Cimmerians within his army on this campaign, possibly for their

knowledge of the Urartuan hills as much as their ability as mounted

warriors. Cimmerians have been raiding into Mesopotamia for decades.

712 BC :

Two

years after he sacks the cult centre of Musasir, Sargon II of Assyria

sacks the neo-Hittite capital of Kummuhu. At the same time Cimmerians

and Scythians invade Anatolia and the city declines. It is possible

that Urartu also suffers from the same tribal incursions, and that

the people responsible eventually destroy the kingdom as they pass

through the region to control the central Zagros Mountains.

695 - 690 BC :

Phrygia

loses the territory of Pergamum to Lydia about 695 BC, seemingly

upon the defeat and suicide of King Midas III. Five years later,

nomadic Cimmerian warriors overrun Phrygia and sack the capital,

Gordion. However, this Cimmerian sacking is also stated to be the

cause of Midas committing suicide, so the situation seems to be

mildly confused. Either way, Lydia becomes the dominant power in

western Anatolia whilst Phrygia is eclipsed.

During this century the Cimmerians and Scythians seem to be wandering over vast distances as warring groups and mercenaries. During the early seventh century they also attack Lydia and Greek coastal cities on the Aegean, and Herodotus states that they are later expelled from there. Place names in Scythia show that Cimmerians are also present in this region at some point. Further involvement, this time when they are allied to the Thracian tribes of the Edoni and Threres, supports a close social and cultural relationship with at least some Thracians, which is confirmed by archaeological discoveries. The Cimmerian presence in Anatolia is archaeologically much more tenuous, probably revealing the briefness of their presence here. Sinope, however, on the Black Sea's southern coast, is suggested as a temporary headquarters for them.

fl 679 BC :

Te-ushpa-a / Te-us-pa-a / Teuspa : Cimmerian king. Killed in 679 BC?

679 BC :

Esarhaddon of Assyria conducts a campaign against the Cimmerians (or Gimirrai as the Assyrians term them). He defeats them and their leader, Te-ushpa-a, in the region of Hubusna (probably Hupisna-Cybistra), but the area is not pacified. In the same year Esarhaddon's troops also fight a war in Hilakku (Khilakku), and a few years later they punish the Anatolian prince of Kundu (Cyinda) and Sissu (Sisium, modern Sis), who has allied himself with Phoenician rebels against Assyrian rule. The regions to the north of the Cilician plain repeatedly cause trouble for Assyria.

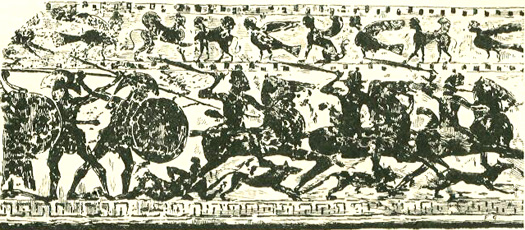

This image shows Cimmerians battling early Greeks - prior to the advent of accepted 'Classical' Greece - with the mounted Cimmerians warriors apparently being accompanied by their dogs (republican Romans did much the same thing) Te-ushpa-a is described as a 'barbarous (?) soldier whose country [is] remote [namely] in the territory of the country of Khu-pu-us-na (Khupushna), together with the whole of his army, I ran through with the sword...' How much of this is propaganda for a home audience and how much fact is entirely unclear.

The typical explanation given for Te-ushpa-a is incorrect. It does not mean 'swelling with strength'. Instead the name is actually a title. It begins with a pronoun 'te', probably meaning 'your'. The second element is 'ushpa', meaning 'high, elevated'. It is cognate with the English 'up', and the Welsh 'uchel', also meaning 'high, elevated', from the proto-Celtic *ouxselo-, meaning 'high'. A rough translation would be 'Your High [person]'. The 'te' pronoun is the same one proposed as being placed in front of the deity (possible form) Waranis or Warunaz (Uranus, Varuna) as it becomes 'tu-waranos' in Celtic, the god Taranus/Taranis, otherwise known as Thor (see the introduction for the kingdom of Upsal for this explanation). The final vowel in his name is probably nominative (suffixes being something that linguists tend to ignore).

fl c.660 - 640 BC :

Tugdamme / Dugdammi : Cimmerian king of the 'Ummân-Manda'. Median king?

c.660 BC :

Tugdamme (or Dugdammi, depending upon the translation of the ancient source material) was also rendered in Greek as Lygdamis. He becomes a Cimmerian king possibly by 660 BC, but is possibly not the only one as the Cimmerians are a tribal group or several groups. The first attacks carried out by him as king of the Ummân-Manda (nomads) seem to be against Greek coastal cities in Anatolia, although the reason for such attacks or for him leading his people around the Black Sea coast to reach the Greek cities is unknown. Population pressure is usually the cause of such semi-migratory expeditions, and this would not be the first time that population pressure in the Pontic-Caspian steppe has caused such a migration.

Fritz Hommel has stated that Tugdamme must be an ancestor of the later Cimmerian ruler, Sandakhshatra. He identifies this ruler as Cyaxares of the Medians, implying that Tugdamme is Phraortes, which seems far less likely than the Sandakhshatra connection. Instead, the name Tugdamme strikes Edward Dawson as being Celtic, with an automatically reconfiguration to the Celtic 'Togodumnos' being an easy leap. Given the possibility that it may be Thraco-Cimmerians who influence the Celtic progression from Hallstatt to La Tène culture during the proposed migration west from the Black Sea, Tugdamme could be a name type that is adopted by the Celts from the Cimmerian warrior elite and is afterwards rendered as Togodumnos (or variants). The alternative is that a reverse migration occurs from Central Europe, perhaps of a small Celtic warrior group coming down the Danube to take command of a Cimmerian group and impose a Celtic leader over them.

653 BC :

Tugdamme begins to threaten the borders of the powerful Assyrian empire during the reign of Ashurbanipal. Assyrian inscriptions record him as being 'King of the Saka and Qutium'. This is very telling, because it suggests that he rules not only over his own Cimmerian people (which is so obvious that it need not be mentioned), but also the Scythians (identifying them as 'Saka', a form of the name that very soon becomes prominent amongst Scythian groups to the east of the Caspian Sea, in Transoxiana).

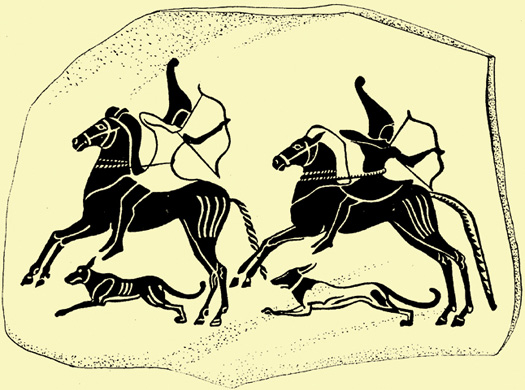

The year 652 BC marked the apogee of Cimmerian power, with their conquest of the kingdom of Lydia, but their supremacy would last only another eleven or so years before defeat and total eclipse The 'Qutium' in point would seem to be 'Gutium', homeland in the Zagros Mountains between modern Iran and Iraq of the nomadic Gutians (often thought to be the precursors of the Kurds). Clearly Tugdamme has already conquered territory very close to the heartland of the Assyrian empire, making it more possible that the Scythian masters of the Medes at this time are in fact the Cimmerians.

Assyrian inscriptions also refer to Tugdamme as 'Sar Kissati' which translates as 'King of Kish' or 'King of the World'. Kish is an ancient and highly important city state in southern Mesopotamia, which suggests that Tugdamme now rules a vast area of land to the east and south of the Assyrians.

652 BC :

One serious invasion of Anatolia by Cimmerians has already been repulsed, with the states or regions of Hilakku, Lydia, and Tabal requesting help from Assyria. Now the Cimmerians return (leader unknown, but Greek tradition states that it is Tugdamme). King Gyges of Lydia is killed during a second attack. His capital of Sardis is captured, all except the citadel which manages to hold out. The fact that it does suggests either that either the Cimmerians do not hang around for long after their victory or that (as before) they are moved along by an Assyrian force (with Ardys II of Lydia helping them on their way at the point of a sword). Excavations at the site of Sardis later discover a destruction layer that appears to be associated with this event.

641 - 640 BC :

After more than a decade of controlling a vast domain, Tugdamme is now defeated. Unfortunately the details of how this happens have failed to survive, so the manner of his defeat and death are unknown. Strabo suggests that Madyas, the Scythian overlord of the Medes, kills him and defeats his forces. Ashurbanipal states that Marduk (also Madyas?) defeats Tugdamme, which seems to support the idea that it is not the Assyrians who kill him but his allies the Scythians.

This would appear to be the point at which the Cimmerians largely break up as a cohesive force. Elements settle in Tabal (Classical Cappadocia) and Thrace, destroy Sinope, and may well also contribute greatly to a thrust of hose-borne warrior groups migrating westwards along the Danube to influence the Celts (even if this is only in terms of cultural and military influences upon Indo-European elements which are already migrating in that direction). Scythian culture takes over in the Caucuses and Pontic steppe, so it is clear that whatever Cimmerians remain there are no longer at all dominant or powerful.

c.600 BC :

The Lydians conquer the southern Anatolian region of Pamphylia and expand the kingdom in all directions, coming into direct contact with Greek settlers in western Anatolia. During this period the kingdom is bordered in the north-east by Scythians and Cimmerians, tribes which are aggressive and unruly, although most of their antagonism is directed towards Assyria. If Fritz Hommel is to believed, that may also be heavily involved with the Medians.

The Cimmerians and Medians appear to have shared a history for the span of about a generation, and with a shared Indo-European heritage they may not have been too divided in cultural terms fl c.600 BC :

Sandakhshatra : Son of Tugdamme? Cimmerian king. Median king?

c.600 BC :

Fritz

Hommel identifies Sandakhshatra with the ruler of Media, Cyaxares,

and his son, Ishtivegu, with Astyages. Both of these names are given

by Herodotus and can be tied to the Median kings, Huwaxshatra and

Ishtumegu, who ruled during or after a period of domination by Scythians.

Hommel also connects the earlier Cimmerian king, Tugdamme, as an

ancestor of Sandakhshatra.

The name Sandakhshatra certainly does seem to be Indo-Iranian in form (and far less Celtic than Tugdamme). Ed Dawson suggests that while it may be Indo-Iranian, it may instead have been 'Iranianised' when written down. Sandaksatru (or Sandakshatra) has an alternative form of Sandakurru, son of the deity Sanda according to Manfred Mayrhofer, although it would be interesting to see the reasoning behind that assertion.

Dawson prefers a spelling of Sandaxatru or Sandaxatra for the original name, but the '-u' or '-a' ending is probably nominative, so even better may be Sandaxatr or Sandaxater. This result leads to speculation that the second element is an altered 'father', so translated perhaps as 'Father Sanda'.

Ishtivegu : Son. Median king?

fl c.580s? BC :

A breakdown of Ishtivegu's name is problematical. The Greek mangling of his name, Astiages, indicates two things: firstly that the 'v' in Ishtivegu is pronounced as a 'w'. Greeks couldn't spell a 'w' in their alphabet and they still struggle with it verbally; secondly the final 'u' of Ishtivegu is probably a nominative suffix. So the name should be Ishtiweg. As for the language used, It does not appear to be Celtic. Pokorny indicates that there is a short phrase as a single word meaning 'I am' or 'he is' - alb. asht (*jesti, aor. ishte), 'he is'. Very simply, 'alb.' literally means Albanian, while 'aor.' is short for 'aorist', both simple verbs in ancient Greek. The only 'weg' that can be found is Germanic for 'fast, in motion', and by extension a path on which to go fast, a 'way'. Greek and German certainly do not fit together here, so for the moment the source of Ishtivegu's name remains unknown.

fl c.450 BC :

Antenor II : Legendary Cimmerian leader.

Antenor II is a legendary leader of the Cimmerians on the Black Sea coast. He is also claimed by later legends as the ancestor of the Sicambri Franks. Fourteen generations of descendants later these Cimmerians are to be found in the forests of Germany to which they have migrated. There they fend off the military attentions of Julius Caesar in the first century BC.

The coast around the Black Sea was claimed as the original homeland of the Franks by later, medieval authors, further obscuring an already legendary origin in Scandinavia According to later Frankish legend, in honour of the mother of Priamus (great-grandson of Antenor) the Cimmerians change the name of their tribe to Sicambri (or, more probably, something closely resembling Cambri, which would suggest that there is no name change at all - Cambri/Cimbri is close enough to Cimmeri for this to be the very source of the later false link to the Germanic Sicambri). Whilst the link to the Sicambri can be discarded, this does seems to point to a specific tribe of Cimmerians rather than all Cimmerians. The migration story itself is likely to be an invention to explain to a medieval audience the similarity between the Cambri and Cimmeri names.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |