| HARRAN

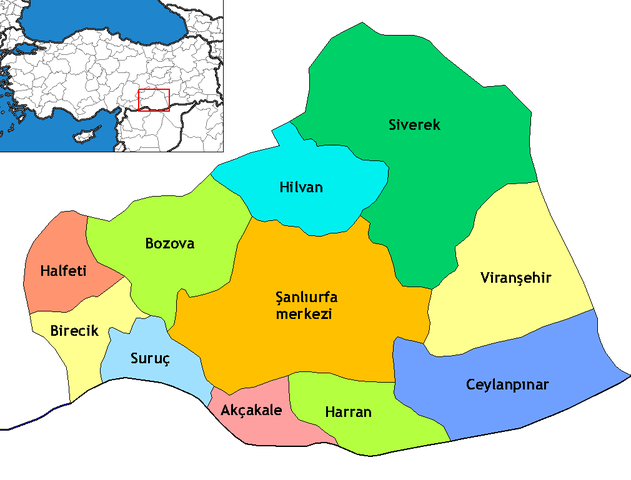

Location of Harran in Turkey

Harran Beehive Houses Harran, also known as Carrhae, was a major ancient city in Upper Mesopotamia whose site is in the modern village of Harran, Turkey, 44 kilometers southeast of Sanliurfa. The location is in the Harran district of Sanliurfa Province.

The archaeological remains are in the ancient Harran, a major commercial, cultural, science and religious center first inhabited in the Chalcolithic Age (6th millennium BCE). The city was called Hellenopolis (Ancient Greek Meaning "Greek city") in the Early Christian period. It is mentioned, in Movses Khorenatsi's and Mikayel Chamchian's History of Armenia, as being under the authority of prince Sanadroug, the sovereignty of which he assigned to Queen Helena of Adiabene.

Names

:

•

Vedic Aryan : Marut

The settlement that would become Harran began as a typical Halaf culture village established circa 6200 BCE as part of the spread of agricultural villages across Western Asia. From its location at the confluence of the Jullab and Balikh rivers it gradually grew in size until a period of rapid urbanization in the following Uruk period. During the Early Bronze Age (3000-2500 BCE) Harran grew into a walled city. The city-state of Harran was part of a network of city-states, called the Kish civilization, centered in the Syrian Levant and upper Mesopotamia. The rise of Harran closely mirrored the similar rise of its trade partners, Ebla, Ugarit, and Alalakh, in a process called secondary urbanization. Its life as a sovereign city-state came to an end when it was annexed into the Akkadian Empire and its successor, the Neo-Sumerian Empire. After the fall of Ur it was again independent for a time, until it was abandoned in the Amorite expansion in 1800 BC. It was later rebuilt as an Assyrian city of Harranu, meaning 'cross-roads' in the Akkadian language.

Bronze

Age :

Royal letters from the city of Mari on the middle of the Euphrates, have confirmed that the area around the Balikh river remained occupied in c. the 19th century BCE. A confederation of semi-nomadic tribes was especially active around the region near Harran at that time.

A temple of the moon god Sin was established sometime at the end of the Neo-Sumerian Empire (circa 2000 BCE). This temple was called the House of Rejoicing (Sumerian: E-hul-hul, Cuneiform: E2.HUL2.HUL2). The ruins of this temple are currently located under the palace of Caliph Marwan II (744-750 CE). Although the exact date of establishment is uncertain, it may have begun as a satellite to the primary moon temple of Nanna in Ur, and then absorbed a refugee priesthood fleeing Ur during warfare in the Isin-Larsa period. Attestation of the temple existence first appears at time of Hammurapi, because he is recorded as signing a treaty there. In fact, Sin of Harran was guarantor of the word of kings between 1900-900 BCE, as his name is witness to the forging of international treaties.

Old Assyrian period :

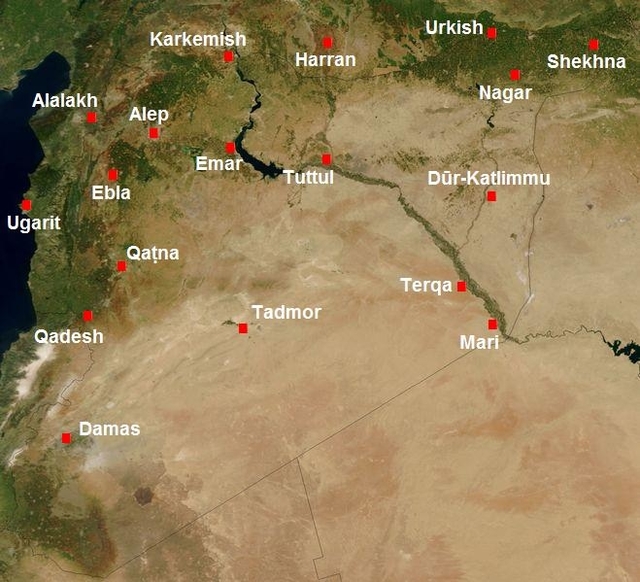

Harran and other major cities of ancient Syria

Harran beehive houses

Ruins of the Harran University By the 20th century BCE, Harran was established as a merchant outpost of the Old Assyrian Empire due to its ideal location. The community, well established before then, was situated along a trade route between the Mediterranean and the plains of the middle Tigris. It lay directly on the road from Antioch eastward to Nisibis and Nineveh. The Tigris could be followed down to the delta to Babylon. The 4th-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (325/330–after 391) said, "From there (Harran) two different royal highways lead to Persia: the one on the left through Neo-Assyrian Adiabene and over the Tigris; the one on the right, through Assyria and across the Euphrates." Not only did Harran have easy access to both the Assyrian and Babylonian roads, but also to north road to the Euphrates that provided easy access to Malatiyah and Asia Minor.

According to Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder, even through the classical period, Harran maintained an important position in the economic life of Assyria.

In its prime Harran was a major Assyrian city which controlled the point where the road from Damascus joins the highway between Nineveh and Carchemish. This location gave Harran strategic value from an early date. Because Harran had an abundance of goods that passed through its region, it became a target for raids. In the 18th century, Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad I (1813–1781 BCE) launched an expedition to secure the Harranian trade route.

Hittite

period :

Middle

and Neo-Assyrian periods :

10th-century BCE inscriptions reveal that Harran had some privileges of fiscal exemption and freedom from certain forms of military obligations. It was even termed the "free city of Harran". During the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Shalmaneser III restored the Temple of Sin in the 9th century BCE, and it was restored again by Ashurbanipal circa 550 BCE. However, in 763 BCE, Harran was sacked during a Harranian rebellion against Assyrian control that resulted in the loss of Harran's privileges. It was not until Sargon II restored order in the late 8th century BCE that those privileges were restored.

Neo-Babylonian

period :

The last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nabonidus, also originated from Harran, as substantiated by evidence from the temple stele of his mother Adad-Guppi, who was of Assyrian origin. Nabonidus made a substantial expansion to the Temple of Sin, and it is from this phase of the temple's operation that it became a famous center of astronomy and knowledge in classical antiquity. The city became a bastion for the worship of the moon god Sin during the rule of Nabonidus in 556–539 BCE, much to the consternation of the city of Babylon in the south, where Marduk remained the primary deity.[better source needed]

Persian

period :

Seleucid

period :

Roman–Sassanid

period :

Centuries later, the emperor Caracalla was murdered here in 217 CE, probably at the instigation of Macrinus. In the 3rd century CE the region was a frontier province of the Roman Empire, being the location for major wars between Rome and Persia. The emperor Galerius was defeated nearby by the Parthians' successors, the Persian Sassanid Empire, in 296 CE.

Post–classical

period :

Hermeticism

:

—

Seyyed Hossein Nasr

It was allegedly the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun who, while passing through Harran on his way to a campaign against the Byzantine Empire, forced the Harranians to convert to one of the "Religions of the Book", meaning Judaism, Christianity, or Islam. The pagan people of Harran identified themselves with the Sabians in order to fall under the protection of Islam. Aramaean and Assyrian Christians remained Christian. Sabians were mentioned in the Qur'an, but they were the group that later mixed Gnostic ideas with their religion and became Mandaeans (a Gnostic sect). The Harranians may have identified themselves as Sabians in order to retain their religious beliefs.

During the late 8th and 9th centuries, Harran was a centre for translating works of astronomy, philosophy, natural sciences, and medicine from Greek to Syriac by Assyrians, and thence to Arabic, bringing the knowledge of the classical world to the emerging Arabic-speaking civilization in the south. Baghdad came to this work later than Harran. Many important scholars of natural science, astronomy, and medicine originated from Harran.

End

of the Sabians :

Crusades

:

At the end of 12th century, Harran served together with Raqqa as a residence of Kurdish Ayyubid princes. The Ayyubid ruler of the Jazira, Al-Adil I, again strengthened the fortifications of the castle. In the 1260s, the city was completely destroyed and abandoned during the Mongol invasions of Syria. The father of the famous Hanbali scholar Ibn Taymiyyah was a refugee from Harran, settling in Damascus. The 13th-century Kurdish historian Abu al-Fida describes the city as being in ruins. The early 14th-century traveler Jordanus devotes Chapter 10 of his Mirabilis to "Aran", which most likely is Harran. The entire chapter reads: "Here Followeth Concerning the Land of Aran. Concerning Aran I say nothing at all, seeing that there is nothing worth noting."

Modern Harran :

Traditional mud brick "beehive" houses in the village of Harran, Turkey

Harran beehive houses

Harran main channel, built as a part of the GAP Project Harran is famous for its traditional "beehive" adobe houses, constructed entirely without wood. The design of these makes them cool inside, suiting the climatic needs of the region, and is thought to have been unchanged for at least 3,000 years. Some were still in use as dwellings until the 1980s. However, those remaining today are strictly tourist exhibits, while most of Harran's population lives in a newly built small village about 2 kilometres away from the main site.

At the historical site, the ruins of the city walls and fortifications are still in place, with one city gate standing, along with some other structures. Excavations of a nearby 4th century BCE burial mound continue under archaeologist Nurettin Yardimci.

The demographics of the village today are made up mostly of ethnic Arabs. It is believed that the ancestors of the villagers were settled here during the 18th century by the Ottoman Empire. The women of the village often have tattoos and are dressed in traditional Bedouin clothes. There are some Assyrian villages in the general area.

By the late 1980s, the large plain of Harran had fallen into disuse as the streams of Cüllab and Deysan, its original water supply, had dried up. However, the plain is now irrigated by the recent Southeastern Anatolia Project, allowing cotton and rice to be grown in the area once again.

Politics :

Districts of Sanliurfa In the local elections of March 2019, Mahmut Özyavuz was elected Mayor. Ömer Faruk Çelik was appointed District Governor as representative of the state.

Religion

:

According to an early Arabic work known as Kitab al-Magall or the Book of Rolls (part of Clementine literature), Harran was one of the cities built by Nimrod (Daksh / Bakus), when Peleg was 50 years old. The Syriac Cave of Treasures (c. 350) contains a similar account of Nimrod's building Harran and the other cities, but places the event when Reu was 50 years old. The Cave of Treasures adds an ancient legend that not long thereafter, Tammuz was pursued to Harran by his wife's lover, B'elshemin, and that he (Tammuz) met his fate there when the city was then burnt.

The pagan residents of Harran also maintained the tradition well into the 10th century AD, [citation needed] of being the site of Tammuz' death, and would conduct elaborate mourning rituals for him each year, in the month bearing his name.

The Christian historian Bar Hebraeus (13th century), mentions in his Chronography that Harran had been built by Cainan (the father of Abraham's ancestor Shelah in some accounts), and had been named for another son of Cainan called Harran.

Sin's temple was rebuilt by several kings, among them the Assyrian Assur-bani-pal (7th century BCE) and the Neo-Babylonian Nabonidus (6th century BCE). Herodian (iv. 13, 7) mentions the town as possessing in his day a temple of the moon.

Harran was a centre of Assyrian Christianity from early on, and was the first place where purpose-built churches were constructed openly. However, many people of Harran retained their ancient pagan faith during the Christian period, and ancient Mesopotamian/Assyrian gods such as Sin and Ashur were still worshipped for a time.

Carrhae was the seat of a Christian diocese before the First Council of Nicaea of 325, which was attended by its bishop Gerontius. In 361, its bishop Barses was transferred to Edessa, the capital of the Roman province of Osrhoene and therefore the metropolitan see of which the bishopric of Carrhae was a suffragan. The names of another eleven bishops of Carrhae, including that of Abraham of Carrhae, are known from then down to Theodore Abu Qurrah, bishop of Carrhae from before 787 to after 813, and the writer of many treatises in Syriac and Arabic. After him, the see passed into the hands of Non-Chalcedonian Jacobite bishops, of whom Michael the Syrian names seventeen who lived between the 8th and the 12th century. No longer a residential bishopric, Carrhae is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.

Harran in scriptures :

Abraham departs out of Haran by Francesco Bassano Harran is, by virtually all scholars, associated with the biblical place Haran (Hebrew: transliterated: Charan). Prior to Sennacherib's reign (704–681 BCE), Harran rebelled against the Assyrians, who reconquered the city (see 2 Kings 19:12 and Isaiah 37:12) and deprived it of many privileges – which King Sargon II later restored.

Biblical Haran was where Terah, his son Abram (Abraham), his nephew Lot, and Abram's wife Sarai settled en route to Canaan, coming from Ur of the Chaldees (Genesis 11:26–32). The region of this Haran is referred to variously as Paddan Aram and Aram Naharaim. Genesis 27:43 makes Haran the home of Laban and connects it with Isaac and Jacob: it was the home of Isaac's wife Rebekah, and their son Jacob spent twenty years in Haran working for his uncle Laban (cf. Genesis 31:38&41).

Very little is known about the pre-mediaeval levels of Harran, especially for the patriarchal times. See Lloyd and Brice.

Archaeology

:

"The grand Mosque of Harran is the oldest mosque built in Anatolia as a part of the Islamic architecture. Also known as the Paradise Mosque, this monument was built by the last Ummayad caliph Mervan II between the years 744–750. The entire plan of the mosque which has dimensions of 104×107 m, along with its entrances, was unearthed during the excavations led by Dr Nurettin Yardimer since 1983. The excavations are currently being carried out also outside the northern and western gates. The grand Mosque, which has remained standing up until today, with its 33.30 m tall minaret, fountain, mihrab, and eastern wall, has gone through several restoration processes".

Excavations in Harran from 2012 to 2013 have focussed on the walls, the mound in the centre of the city and the Castle (kale). In 2012 and 2013, the Sanliurfa Museum Directorate, with Professor Mehmet Önal (Professor of Archaeology at Harran University) acting as consultant, carried out excavation works for restoration purposes on the western part of the city wall, uncovering the walls, towers and bastions. In excavations in the northern part of the Castle, a gallery and crenellated corridor were discovered on the west side. Near the south-east gate, a Greek inscription was found set in a wall and the remains of an inscribed pink marble ambo were found in the spolia infill of a wall in of the main west entrance-tower. In 2014, following a decision of the Council of Ministers and courtesy of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, further excavation work was conducted, again under the direction of Professor Önal. In these works, near Harran's Great Mosque, the Bazaar Bathhouse, the Eastern Bazaar, the Vaulted Road Bazaar, Public Toilets and a perfumery shop and workshop were uncovered. In the Eastern Bazaar many fragments of glass lamps, mortar and fallen shelves were found in one shop, while in another scales, weights and metal artifacts were recovered and in the perfumery hundreds of sphero-conical vessels were found, having fallen from the shelves. In 2016, excavations were carried out on the city wall (west of the southern, "Raqqa" Gate), revealing part of the wall and leading to the discovery of a broken statue of a woman with a Syriac inscription and a male relief, both used as spolia in the wall. In the 2014–2016 excavations carried out in the west side of the Castle, a crenellated corridor belonging to a second defense system adjacent to the wall of the Castle (between the polygonal and rectangular towers) was uncovered. The excavations in 2017–2018 in the southern part of the Castle located its bathhouse on the second storey. The bathhouse is well preserved, with a cold room (frigidarium), dressing room, warm room (tepidarium), hot room (caldarium), hypocaust and furnace (praefurnium). Excavations were also carried out on the north-west of the mound at the centre of the site, where houses of the Zengid and Ayyubid periods, pottery, coins etc. were found in the upper layers, and mudbrick walls, figurines and pottery sherds belonging to the Bronze Age in the lower layers. On the east of the mound, a cuneiform brick of Iron Age date was found in the upper layers and mud-brick walls of the Bronze Age in the lower layers, as well as the skeletons of a woman and children, terra-cotta figurines, Chalcolithic stamp seals, ceramic pieces, etc. In 2019, a hall to the north of the Castle bathhouse and another crenellated corridor in front of the south-east gate were partially exposed. The excavations planned for 2020 will focus on the Castle, eastern part of Great Mosque and the central mound.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harran |