| BURNABURIASH II

Seal dedicated to Burna-Buriash II Reign

: 1359 – 1333 BC

House : Kassite

Burnaburiash II / Burna-Buriash II / Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as Bur-na- or Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning servant or protégé of the Lord of the lands in the Kassite language, where Buriaš (dbu-ri-ia-aš2) is a Kassite storm god possibly corresponding to the Greek Boreas, was a king in the Kassite dynasty of Babylon, in a kingdom contemporarily called Karduniaš, ruling ca. 1359–1333 BC, where the Short and Middle chronologies have converged. Recorded as the 19th King to ascend the Kassite throne, he succeeded Kadašman-Enlil I, who was likely his father, and ruled for 27 years. He was a contemporary of the Egyptian Pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. The proverb "the time of checking the books is the shepherds' ordeal" was attributed to him in a letter to the later king Esarhaddon from his agent Mar-Issar.

Correspondence

with Egypt :

But then things began to sour. On EA 10, he complains that the gold sent was underweight. "You have detained my messenger for two years!" he declares in consternation. He reproached the Egyptian for not having sent his condolences when he was ill and, when his daughter's wedding was underway, he complained that only five carriages were sent to convey her to Egypt. The bridal gifts filled 4 columns and 307 lines of cuneiform inventory on tablet EA 13.

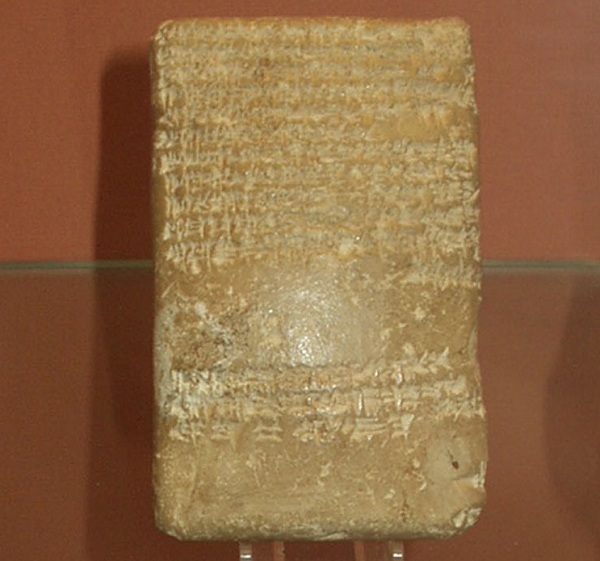

Reverse of clay cuneiform tablet, EA 9, letter from Burna-Buriaš II to Nibhurrereya (Tutankhamun?) from Room 55 of the British Museum Not only were matters of state of concern. "What you want from my land, write and it shall be brought, and what I want from your land, I will write, that it may be brought." But even in matters of trade, things went awry and, in EA 8, he complains that Egypt's Canaanite vassals had robbed and murdered his merchants. He demanded vengeance, naming Šum-Adda, the son of Balumme, affiliation unknown, and Šutatna, the son of Šaratum of Akka, as the villainous perpetrators.

In his correspondence with the Pharaohs, he did not hesitate to remind them of their obligations, quoting ancient loyalties :

In the time of Kurgalzu, my ancestor, all the Canaanites wrote here to him saying, "Come to the border of the country so we can revolt and be allied with you." My ancestor sent this (reply), saying, “Forget about being allied with me. If you become enemies of the king of Egypt, and are allied with anyone else, will I not then come and plunder you?”… For the sake of your ancestor my ancestor did not listen to them. -

Burna-Buriaš, from tablet EA 9, BM 29785, line 19 onward.

With regard to the Kassites… Though the house is well fortified, they attempted a very serious crime. They took their tools, and I had to seek shelter by a support for the roof. And so if he (pharaoh) is going to send troops into Jerusalem, let them come with a garrison for regular service…. And please make the Kassites responsible for the evil deed. I was almost killed by the Kassites in my own house. May the king make an inquiry in their regard.

-

Abdi-Heba, El-Amarna tablet EA 287.

International relations :

Bronze statue of Napir-asu in the Louvre Diplomacy with Babylon's neighbor, Elam, was conducted through royal marriages. A Neo-Babylonian copy of a literary text which takes the form of a letter, now located in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, is addressed to the Kassite court by an Elamite King. It details the genealogy of the Elamite royalty of this period, and from it we find that Pahir-Iššan married Kurigalzu I's sister and Humban-Numena married his daughter and their son, Untash-Napirisha was betrothed to Burna-Buriaš's daughter. This may have been Napir-asu, whose headless statue (pictured) now resides in the Louvre in Paris.

It is likely that Suppiluliuma I, king of the Hittites, married yet another of Burna Buriaš's daughters, his third and final wife, who thereafter was known under the traditional title Tawananna, and this may have been the cause of his neutrality in the face of the Mitanni succession crisis. He refused asylum to the fleeing Shattiwaza, who received a more favorable response in Hatti, where Suppiluliuma I supported his reinstatement in a diminished vassal state. According to her stepson Mursili II, she became quite a troublemaker, scheming and murderous, as in the case of Mursili's wife, foisting her strange foreign ways on the Hittite court and ultimately being exiled. His testimony is preserved in two prayers in which he condemned her.

Kassite influence reached to Bahrain, ancient Dilmun, where two letters found in Nippur were sent by a Kassite official, Ili-ippašra, in Dilmun to Ililiya, a hypocoristic form of Enlil-kidinni, who was the governor, or šandabakku, of Nippur during Burna Buriaš's reign and that of his immediate successors. In the first letter, the hapless Ili-ippašra complains that the anarchic local Ahlamû tribesmen have stolen his dates and "there is nothing I can do" while in the second letter they "certainly speak words of hostility and plunder to me".

Domestic

affairs :

The foundation record of Ebarra which Burna-buriaš, a king of former times, my predecessor, had made, he saw and upon the foundation record of Burna-buriaš, not a finger-breadth too high, not a finger-breadth beyond, the foundation of that Ebarra he laid.

-

Inscription of Nabonidus, cylinder BM 104738.

Kara-hardaš,

Nazi-Bugaš, and the events at the end of his reign :

Perhaps to cement relations, Muballitat-Šerua, daughter of Aššur-uballit, had been married to either Burna-Buriaš or possibly his son, Kara-hardaš; the historical sources do not agree. The scenario proposed by Brinkman has come to be considered the orthodox interpretation of these events. A poorly preserved letter in the Pergamon Museum possibly mentions him and a princess or marat šarri. Kara-hardaš was murdered, shortly after succeeding his father to the throne, during a rebellion by the Kassite army in 1333 BC. According to an Assyrian chronicle this incited Aššur-uballit to invade, depose the usurper installed by the army, one Nazi-Bugaš or Šuzigaš, described as "a Kassite, son of a nobody", and install Kurigalzu II, "the younger", variously rendered as son of Burnaburiaš and son of Kadašman-Harbe, likely a scribal error for Kara-hardaš. Note, however, that there are more than a dozen royal inscriptions of Kurigalzu II identifying Burna-Buriaš as his father.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burna-Buriash_II |

.jpg)