| NINSU / NINSUN

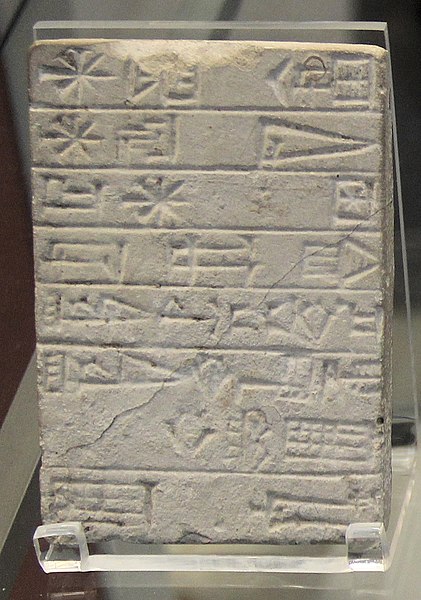

Relief with an inscription mentioning Ninsun. Louvre Museum

Ninsu / Ninsun : Goddess of wild cows, mother of Gilgamesh

Other

names : Ninsumuna

Ninsun (also called Ninsumun, cuneiform : dNIN.SUMUN2; Sumerian: Nin-sumun(ak) "lady of the wild cows") was a Mesopotamian goddess. She is best known as the mother of the hero Gilgamesh and wife of deified legendary king Lugalbanda, and appears in this role in most versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh. She was associated with Uruk, where she lives in this composition, but she was also worshiped in other cities of ancient Mesopotamia, such as Nippur and Ur, and her main cult center was the settlement KI.KALki.

The degree of Ninsun's involvement in Gilgamesh's life varies between various versions of the Epic. She only plays an active role in the so-called "Standard Babylonian" version, in which she advises her son and interprets his dreams, petitions the sun god Shamash to protect him, and accepts Enkidu as a member of her family. In the Old Babylonian version her role is passive, with her actions being merely briefly discussed by Shamhat, while a Hittite translation of the text omits her altogether. She is additionally present in older Sumerian compositions, including Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, as well as a poorly preserved and very early myth describing her first meeting with Lugalbanda and their marriage.

Kings from the Third Dynasty of Ur regarded Ninsun as their divine mother, and Gilgamesh as their brother, most likely to legitimize their claim to rule over Mesopotamia. Ur-Nammu and Shulgi both left behind inscriptions attesting their personal devotion to this goddess, and a prince only known from a single attestation bore the theophoric name Puzur-Ninsun.

The god list An = Anum mentions multiple children of Ninsun and her husband Lugalbanda separately from Gilgamesh. A sparsely attested tradition additionally regarded her as the mother of the dying god Dumuzi, indicating a degree of conflation with his usual mother Duttur. She could also be equated with the medicine goddess Gula, especially in syncretic hymns.

Character

:

In texts from Lagash, Ninsun is sometimes referred to as a lamma. In this context, lamma most likely should be understood as a designation of a deity's function, namely their involvement in granting long and prosperous life to devotees. It is possible that "Lamma-Ninsumuna" was envisioned as leading Lugalbanda by the wrist, even though lamma goddesses were usually described as walking behind the person they protected. It is also probable that in some cases Ninsun was believed to bestow a lamma upon kings. An inscription of Ur-Ningirsu I identifies her with the goddess Lammašaga, usually viewed as the sukkal of Bau. Claus Wilcke argues that in this case the name Lammašaga should be only understood as a descriptive epithet.

The so-called "Pennsylvania tablet" of the Old Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh attests that Ninsun was believed to be capable of dream interpretation.

Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur, as well as Gudea of Lagash, regarded Ninsun as their divine mother. However, there is no evidence that Ninsun was ever regarded as a mother goddess similar to Aruru or Ninhursag.

Associations

with other deities :

Ninsun was regarded as the mother of the deified hero Gilgamesh, as already attested in Sumerian poems about him. She is consistently attested in this role in various versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The identity of Gilgamesh's father is not mentioned in the Old Babylonian version, and traditions where his identity was left unspecified are known, for example a king list simply refers to him as a "phantom" (líl-lá), but due to the preexisting association with Ninsun Lugalbanda was widely accepted as the hero's father in Mesopotamian tradition, and references are known from other texts, for example the Poem of the Mattock. As there is no indication that Ninsun was ever envisioned as a mortal woman, rather than a goddess, references to deceased mother of Gilgamesh present in the text Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld most likely refer to an unrelated tradition regarding the hero's origin.

The god list An = Anum enumerates ten deities regarded as children of Ninsun and Lugalbanda alongside them. The first among them, a goddess named Šilamkurra, was worshiped in Uruk in the Seleucid period, where she appears in a ritual text alongside Usur-amassu, Ninimma and otherwise unknown Ninurbu. In An = Anum, Gilgamesh occurs separately from Ninsun and her other family members on a different tablet, possibly in the company of Enkidu though the restoration of the latter's name is uncertain. A sukkal (attendant deity) of Ninsun appears in the same list after Lugalbanda's sukkal Lugalhegal, but the full name cannot be fully restored due to the state of preservation of the tablet. According to Richard L. Litke, the name starts with lugal and ends with an-na, but one more sign present between these two elements is not preserved.

There is evidence that as early as in the Old Babylonian period, Ninsun could be equated with Gula in theological texts, for example in two column versions of the Weidner god list. An association between these two goddesses is also present in the Hymn to Gula composed by Bullu?sa-rabi, which identifies the eponymous goddess with a large number of other female deities, among them Nintinugga, Ninkarrak, Nanshe and Ninigizibara. Joan Goodnick Westenholz notes that while syncretism between different medicine goddesses is not unusual, the presence of Ninsun in this text is, especially since it preserves information about her usual character instead of reinterpreting her as another similar deity. A similar equation between Ninsun's and Gula's respective husbands, Lugalbanda and Ninurta, is also attested, though it was likely secondary and there is no evidence Ninurta was ever referred to as Gilgamesh's father.

Ninsun could also be identified with the mother of Dumuzid, Duttur, which according to Manfred Krebernik indicates that the latter was likely viewed as a goddess associated with livestock in general rather than specifically with sheep, as originally proposed by Thorkild Jacobsen. It is also possible that this equation was the result of the network of associations between Dumuzid, Damu, and kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur, who referred to Gilgamesh as their brother. Dina Katz proposes that it was inspired by king lists, in which Dumuzi the Fisherman (a figure distinct from the god Dumuzid) is listed between Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh, though without being labeled as a son of the former. In at least one case, Dumuzid is called the son of both Ninsun and Lugalbanda. An indirect association between Dumuzid and Ninsun is also present in an inscription of Utuhegal, in which Gilgamesh, directly called the son of this goddess, assigns Dumuzid to him as a bailiff.

Worship :

Ur-Nammu's dedication tablet for the temple of Ninsun in Ur: "For his lady Ninsun, Ur-Nammu the mighty man, King of Ur and King of Sumer and Akkad, has built her temple" Ninsun has been characterized as a "well-known goddess in all periods." She is already attested in the Early Dynastic god lists from Fara and Abu Salabikh. Her main cult center was KI.KALki, but she was also worshiped in Lagash, Nippur, Ur, Uruk, Ku'ara, Umma and other settlements. A temple dedicated to her existed in Ur, as attested in an inscription of Ur-Nammu, which states that it was rebuilt by this ruler and that it bore the name E-mah, "exalted house." A temple dedicated to her known as E-gula, "big house," is also known, but its location is not specified in known documents, and the same name was also applied to a large number of other houses of worship in various parts of Mesopotamia. In the "Standard Babylonian" edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Egalmah ("exalted palace") is said to be Ninsun's temple in Uruk, but an inscription of Sîn-kašid indicates it was originally a temple of Ninisina, while in a document from the first millennium BCE the deity worshiped in it is Belet-balati, a manifestation of closely connected Gula. Sîn-kašid also built a temple of Lugalbanda and Ninsun bearing the name E-Kikal, "house, precious place."

An inscription of Gudea addresses Ninsun as his divine mother. However, there are also cases where he referred to Nanshe or Gatumdag as such. Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur also described Ninsun as their divine mother. For example, in Death of Ur-Nammu, Ninsun mourns the passing of the eponymous king and is addressed as his mother. By extension, the rulers also treated Gilgamesh as their divine brother, and Ur-Nammu's successor Shulgi called Lugalbanda his divine father. It is possible that one of this king's daughters served as the en priestess of Ninsun. It is agreed that claiming descent from Ninsun was viewed as a way to legitimize their rule, but it is unknown whether it should be understood as a sign that the dynasty originated in Uruk, or if the only reason was the fact that Gilgamesh was recognized as a model of kingship. In addition to the kings, there is also evidence for worship of Ninsun by their families. A concubine of Shulgi, Šuqurtum, referred to Ninsun as "my goddess" in a curse formula on an inscribed vase. A prince (dumu lugal) bearing the theophoric name Puzur-Ninsun is also known, but no detailed information about his life is presently known, and the Puzrish-Dagan tablet attesting his existence is undated.

Ninsun continued to be worshiped in later periods. Sporadic references to her are present in Old Babylonian personal letters. In cylinder seal inscriptions from Sippar, Ninsun and Lugalbanda occur less commonly than the most popular divine couples, such as Shamash and Aya and Adad and Shala, but with comparable frequency as Enlil and Ninlil or Nanna and Ningal. Ninsun continues to appear in seal inscriptions from Kassite period as well. In Seleucid Uruk, Ninsun was celebrated during the New Year festival of Ishtar. Most of the deities involved in it were well known as members of the pantheon of Uruk, in contrast with a different group which was celebrated during an analogous festival of Antu.

Mythology

:

Ninsun appears in some copies of the Sumerian myth Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven. She advises her son to reject Inanna's proposals and gifts.

In the Old Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the eponymous hero asks Ninsun to interprets his dreams foretelling the arrival of Enkidu. In the younger versions of the composition, this is not shown directly, but rather mentioned by Shamhat to Enkidu. Ninsun predicts that Gilgamesh and Enkidu will become close (according to Andrew R. George: that they will become lovers), which comes true after their subsequent duel. In the "Standard Babylonian" version, the heroes later visit Ninsun in her temple in Uruk. She prays to Shamash to take care of her son, even though she is aware of the fate awaiting him. She also asks Shamash's wife Aya to intercede on her Gilgamesh's behalf. She manages to convince Shamash to give Gilgamesh thirteen winds meant to help him on the way to the Cedar Forest. At one point, she acknowledges that he is destined to dwell in the underworld alongside deities such as Ningishzida and Irnina. The final lines are damaged, but Ninsun seemingly holds Shamash responsible for Gilgamesh's plan to journey to distant lands, and therefore expects him to help him. It has been noted that overall the later version expands Ninsun's role, as in the Old Babylonian version, Gilgamesh prays to Shamash himself, without his mother's intercession. Both Ninsun and the dream sequences are absent from the Hittite translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh known from Hattusa.

After finishing her prayer to Shamash, Ninsun decides to meet with Enkidu and proclaims him as equal to her son in rank and a member of her family. The scene has been conventionally interpreted as representing adoption. There is no evidence that an analogous plot point was present in the Old Babylonian versions. Andrew R. George proposes that the passage reflected a custom known from neo-Babylonian and later documents from Uruk, according to which foundlings and orphans were raised in temples, though their divine protectors were the anonymous "Daughters of Eanna" rather than Ninsun. A different interpretation has been proposed by Nathan Wasserman, who assumes that by adopting Enkidu, Ninsun guaranteed his loyalty to Gilgamesh and the city of Uruk. He argues that Enkidu's actions during the confrontation with Humbaba indicate that he valued Ninsun's acceptance highly, as he seemingly tells Gilgamesh to ignore the monster's pleas because the latter earlier mocked him as a being with no family.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ninsun |