| SARGON / UR-NANSHE / UR-NINA

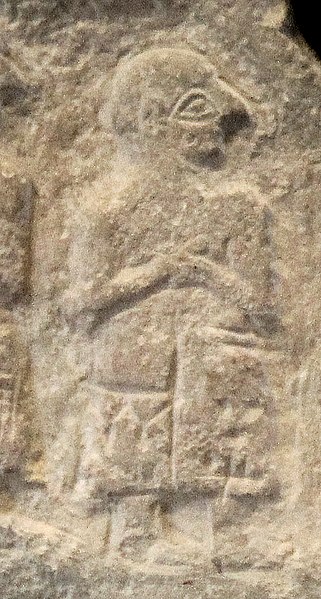

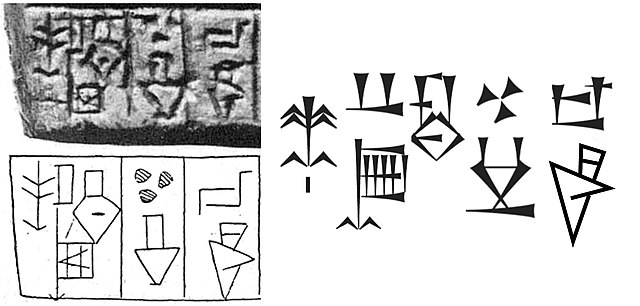

Sargon of Akkad on his victory stele, with inscription "King Sargon" (Šar-ru-gi lugal) vertically inscribed in front of him

King of the Akkadian Empire

Reign : c. 2334 – 2284 BC (MC)

Successor : Mush / Uru-Mush / Rimush

Spouse : Tashlultum

Issue : Menes / Manishtushu, Rimush, Enheduanna, Ibarum, Abaish-Takal

Dynasty : Akkadian (Sargonic)

Father

: La'ibum

/ Gunidu

Sargon of Akkad (Šar-ru-gi), also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC. He is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire.

He was the founder of the "Sargonic" or "Old Akkadian" dynasty, which ruled for about a century after his death until the Gutian conquest of Sumer. The Sumerian king list makes him the cup-bearer to king Ur-Zababa of Kish. He is not to be confused with Sargon I, a later king of the Old Assyrian period.

His empire is thought to have included most of Mesopotamia, parts of the Levant, besides incursions into Hurrite and Elamite territory, ruling from his (archaeologically as yet unidentified) capital, Akkad (also Agade).

Sargon appears as a legendary figure in Neo-Assyrian literature of the 8th to 7th centuries BC. Tablets with fragments of a Sargon Birth Legend were found in the Library of Ashurbanipal.

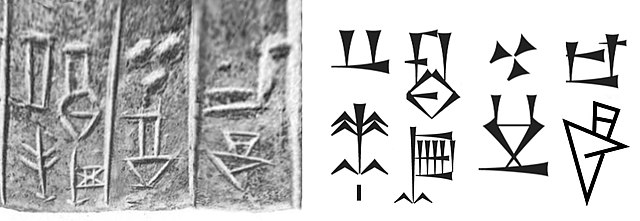

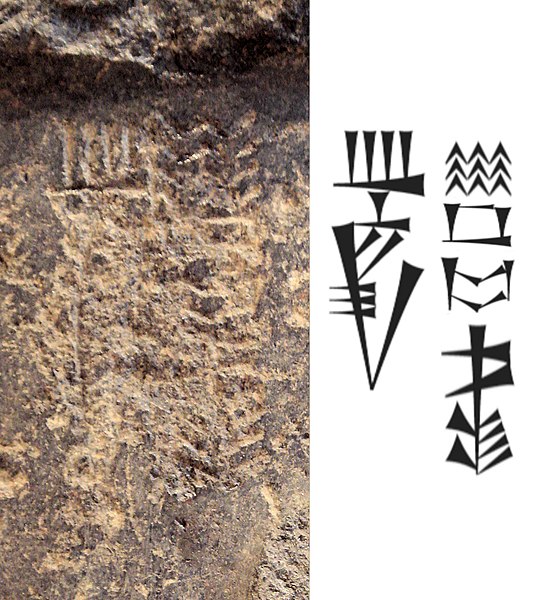

Name :

"King Sargon" (Šar-ru-gi lugal) on the Victory stele of Sargon The Akkadian name is normalized as either Šarru-ukin or Šarru-ken. The name's cuneiform spelling is variously LUGAL-ú-kin, šar-ru-gen, šar-ru-ki-in, šar-ru-um-ki-in. In Old Babylonian tablets relating the legends of Sargon, his name is transcribed as Šar-ru-um-ki-in. In Late Assyrian references, the name is mostly spelled as LUGAL-GI.NA or LUGAL-GIN, i.e. identical to the name of the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II.

A possible interpretation of the reading Šarru-ukin is "the king has established (stability)" or "he [the god] has established the king". Such a name would however be unusual; other names in -ukin always include both a subject and an object, as in Šamaš-šuma-ukin "Shamash has established an heir". There is some debate over whether the name was an adopted regnal name or a birth name. The reading Šarru-ken has been interpreted adjectivally, as "the king is established; legitimate", expanded as a phrase šarrum ki(e)num.

The terms "Pre-Sargonic" and "Post-Sargonic" were used in Assyriology based on the chronologies of Nabonidus before the historical existence of Sargon of Akkad was confirmed. The form Šarru-ukin was known from the Assyrian Sargon Legend discovered in 1867 in Ashurbanipal's library at Nineveh. A contemporary reference to Sargon thought to have been found on the cylinder seal of Ibni-sharru, a high-ranking official serving under Sargon. Joachim Menant published a description of this seal in 1877, reading the king's name as Shegani-shar-lukh, and did not yet identify it with "Sargon the Elder" (who was identified with the Old Assyrian king Sargon I).

In 1883, the British Museum acquired the "mace-head of Shar-Gani-sharri", a votive gift deposited at the temple of Shamash in Sippar. This "Shar-Gani" was identified with the Sargon of Agade of Assyrian legend. The identification of "Shar-Gani-sharri" with Sargon was recognised as mistaken in the 1910s. Shar-Guni / Shar-Gani-sharri (Shar-Kali-Sharri) is, in fact, Sargon's great-grandson, the successor of Narmar / Naram-Sin / Vishva.

It is not entirely clear whether the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II was directly named for Sargon of Akkad, as there is some uncertainty whether his name should be rendered Šarru-ukin or as Šarru-ken(u).

Chronology :

Map of the approximate extent of the Akkadian Empire during the reign of Sargon's grandson, Naram-Sin of Akkad Primary sources pertaining to Sargon are sparse; the main near-contemporary reference is that in the various versions of the Sumerian King List. Here, Sargon is mentioned as the son of a gardener, former cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa of Kish. He usurped the kingship from Lugal-zage-si of Uruk and took it to his own city of Akkad. Various copies of the king list give the duration of his reign as either 54, 55 or 56 years. Numerous fragmentary inscriptions relating to Sargon are also known.

In absolute years, his reign would correspond to ca. 2334–2284 BC in the middle chronology. His successors until the Gutian conquest of Sumer are also known as the "Sargonic Dynasty" and their rule as the "Sargonic Period" of Mesopotamian history.

Foster (1982) argued that the reading of 55 years as the duration of Sargon's reign was, in fact, a corruption of an original interpretation of 37 years. An older version of the king list gives Sargon's reign as lasting for 40 years.

Thorkild Jacobsen marked the clause about Sargon's father being a gardener as a lacuna, indicating his uncertainty about its meaning. Ur-Zababa and Lugal-zage-si are both listed as kings, but separated by several additional named rulers of Kish, who seem to have been merely governors or vassals under the Akkadian Empire. The claim that Sargon was the original founder of Akkad has been called into question with the discovery of an inscription mentioning the place and dated to the first year of Enshakushanna, who almost certainly preceded him. The Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19:51) states that it was Sargon who "built Babylon in front of Akkad." The Chronicle of Early Kings (ABC 20:18–19) likewise states that late in his reign, Sargon "dug up the soil of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade". Van de Mieroop suggested that those two chronicles may refer to the much later Assyrian king, Sargon II of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, rather than to Sargon of Akkad.

Some of the regnal year names of Sargon are preserved, and throw some light in the events of his reign, particularly the conquest of the surrounding territories of Simurrum, Elam and Mari, and Uru'a, thought to be a city in Elam :

1.

Year in which Sargon went to Simurrum

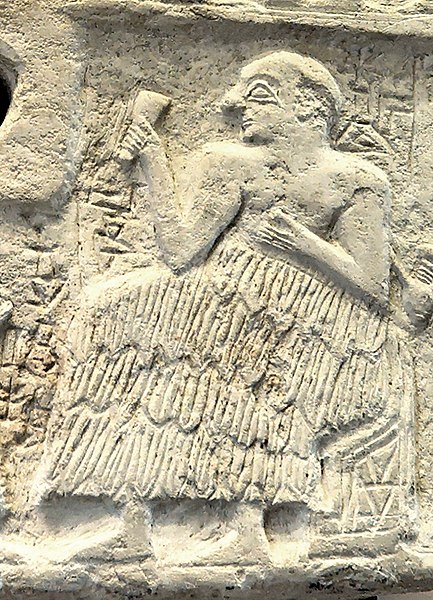

Historiography : Victory stele of Sargon

The stele, with Sargon leading a procession

King Sargon

Fragment of the Victory Stele of Sargon, showing Sargon with a royal

hair bun, holding a mace and wearing a kaunakes flounced royal coat

on his left shoulder with a large belt (left), followed by an attendant

holding a royal umbrella (center) and a procession of dignitaries

holding weapons. The name of Sargon in cuneiform (Akkadian: Šar-ru-gi

lugal "King Sargon") appears faintly in front of his face.

Clothing is comparable to those seen on the cylinder seal of Kalki,

in which appears the likely brother of Sargon. Circa 2300 BCE. Louvre

Museum. Numerous other inscriptions related to Sargon are known.

Sargon appears to have promoted the use of Semitic (Akkadian) in inscriptions. He frequently calls himself "king of Akkad" first, after the city of Akkad which he apparently founded. He appears to have taken over the rule of Kish at some point, and later also much of Mesopotamia, referring to himself as "Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land [Mesopotamia], governor (ensi) of Enlil".

While various copies of the Sumerian king list credit Sargon with a 56, 55, or 54-year reign, dated documents have been found for only four different year-names of his actual reign. The names of these four years describe his campaigns against Elam, Mari, Simurrum (a Hurrian region), and Uru'a (an Elamite city-state).

During Sargon's reign, East Semitic was standardized and adapted for use with the cuneiform script previously used in the Sumerian language into what is now known as the "Akkadian language". A style of calligraphy developed in which text on clay tablets and cylinder seals was arranged amidst scenes of mythology and ritual.

Nippur inscription :

Prisoners escorted by a soldier, on a victory stele of Sargon of Akkad, circa 2300 BCE. Probably from the end of Sargon's reign. The hairstyle of the prisoners (curly hair on top and short hair on the sides) is characteristic of Sumerians, as also seen on the Standard of Ur. Louvre Museum Among the most important sources for Sargon's reign is a tablet of the Old Babylonian period recovered at Nippur in the University of Pennsylvania expedition in the 1890s. The tablet is a copy of the inscriptions on the pedestal of a Statue erected by Sargon in the temple of Enlil. Its text was edited by Arno Poebel (1909) and Leon Legrain (1926).

Conquest

of Sumer :

Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land, governor of Enlil: he defeated the city of Uruk and tore down its walls, in the battle of Uruk he won, took Lugalzagesi king of Uruk in the course of the battle, and led him in a collar to the gate of Enlil. -

Inscription of Sargon (Old Babylonian copy from Nippur).

Sargon, king of Agade, was victorious over Ur in battle, conquered the city and destroyed its wall. He conquered Eninmar, destroyed its walls, and conquered its district and Lagash as far as the sea. He washed his weapons in the sea. He was victorious over Umma in battle, [conquered the city, and destroyed its walls]. [To Sargon], lo[rd] of the land the god Enlil [gave no] ri[val]. The god Enlil gave to him [the Upper Sea and] the [Lower Sea]. -

Inscription of Sargon. E2.1.1.1

Sargon the King bowed down to Dagan in Tuttul. He (Dagan) gave to him (Sargon) the Upper Land: Mari, Iarmuti, and Ebla, as far as the Cedar Forest and the Silver Mountains

-

Nippur inscription of Sargon.

Sargon triumphed over 34 cities in total. Ships from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun, rode at anchor in his capital of Akkad.

He entertained a court or standing army of 5,400 men who "ate bread daily before him".

Sargon Epos :

Cylinder seal of the scribe Kalki, showing Prince Ubil-Eshtar, probable brother of Sargon, with dignitaries (an archer in front, two dignitaries, and the scribe holding a tablet following the Prince). Inscription: "Ubil-Aštar, brother of the king: KAL-KI the scribe, (is) his servant" A group of four Babylonian texts, summarized as "Sargon Epos" or Res Gestae Sargonis, shows Sargon as a military commander asking the advice of many subordinates before going on campaigns. The narrative of Sargon, the Conquering Hero, is set at Sargon's court, in a situation of crisis. Sargon addresses his warriors, praising the virtue of heroism, and a lecture by a courtier on the glory achieved by a champion of the army, a narrative relating a campaign of Sargon's into the far land of Uta-raspashtim, including an account of a "darkening of the Sun" and the conquest of the land of Simurrum, and a concluding oration by Sargon listing his conquests.

Akkadian official in the retinue of Sargon of Akkad, holding an axe The narrative of King of Battle relates Sargon's campaign against the Anatolian city of Purushanda in order to protect his merchants. Versions of this narrative in both Hittite and Akkadian have been found. The Hittite version is extant in six fragments, the Akkadian version is known from several manuscripts found at Amarna, Assur, and Nineveh. The narrative is anachronistic, portraying Sargon in a 19th-century milieu. The same text mentions that Sargon crossed the Sea of the West (Mediterranean Sea) and ended up in Kuppara, which some authors have interpreted as the Akkadian word for Keftiu, an ancient locale usually associated with Crete or Cyprus.

Famine and war threatened Sargon's empire during the latter years of his reign. The Chronicle of Early Kings reports that revolts broke out throughout the area under the last years of his overlordship:

Afterward in his [Sargon's] old age all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Akkad; and Sargon went onward to battle and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed. Afterward he attacked the land of Subartu in his might, and they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled that revolt, and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed, and he brought their possessions into Akkad. The soil from the trenches of Babylon he removed, and the boundaries of Akkad he made like those of Babylon. But because of the evil which he had committed, the great lord Marduk was angry, and he destroyed his people by famine. From the rising of the sun unto the setting of the sun they opposed him and gave him no rest.

A. Leo Oppenheim translates the last sentence as "From the East to the West he [i.e. Marduk] alienated (them) from him and inflicted upon (him as punishment) that he could not rest (in his grave)."

Chronicle of Early Kings :

Prisoner in a cage, probably king Lugalzagesi of Uruk, being hit on the head with a mace by Sargon of Akkad. Akkadian Empire victory stele circa 2300 BCE. Louvre Museum Shortly after securing Sumer, Sargon embarked on a series of campaigns to subjugate the entire Fertile Crescent. According to the Chronicle of Early Kings, a later Babylonian historiographical text:

[Sargon] had neither rival nor equal. His splendor, over the lands it diffused. He crossed the sea in the east. In the eleventh year he conquered the western land to its farthest point. He brought it under one authority. He set up his statues there and ferried the west's booty across on barges. He stationed his court officials at intervals of five double hours and ruled in unity the tribes of the lands. He marched to Kazallu and turned Kazallu into a ruin heap, so that there was not even a perch for a bird left.

In the east, Sargon defeated four leaders of Elam, led by the king of Awan. Their cities were sacked; the governors, viceroys, and kings of Susa, Warahše, and neighboring districts became vassals of Akkad.

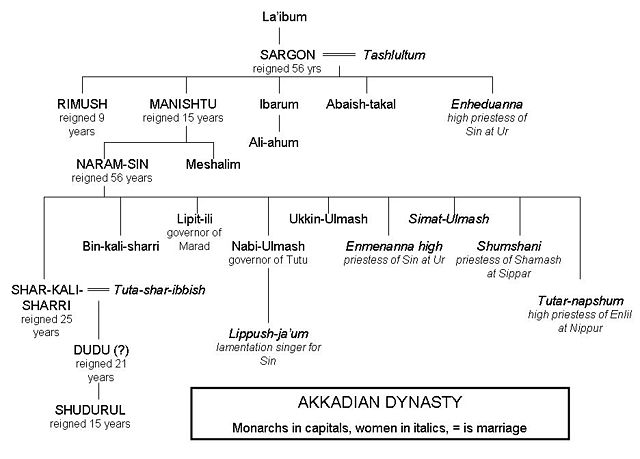

Family :

The name of Sargon's main wife, Queen Tashlultum, and those of a number of his children are known to us. His daughter Enheduanna was a priestess who composed ritual hymns. Many of her works, including her Exaltation of Inanna, were in use for centuries thereafter. Sargon was succeeded by his son Rimush; after Rimush's death another son, Manishtushu, became king. Manishtushu would be succeeded by his own son, Naram-Sin. Two other sons, Shu-Enlil (Ibarum) and Ilaba'is-takal (Abaish-Takal), are known.

Family tree of Sargon of Akkad Legacy :

Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon Sargon of Akkad is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire (in the sense of the central government of a multi-ethnic territory), although earlier Sumerian rulers such as Lugal-zage-si might have a similar claim. His rule also heralds the history of Semitic empires in the Ancient Near East, which, following the Neo-Sumerian interruption (21st/20th centuries BC), lasted for close to fifteen centuries until the Achaemenid conquest following the 539 BC Battle of Opis.

Sargon was regarded as a model by Mesopotamian kings for some two millennia after his death. The Assyrian and Babylonian kings who based their empires in Mesopotamia saw themselves as the heirs of Sargon's empire. Sargon may indeed have introduced the notion of "empire" as understood in the later Assyrian period; the Neo-Assyrian Sargon Text, written in the first person, has Sargon challenging later rulers to "govern the black-headed people" (i.e. the indigenous population of Mesopotamia) as he did. An important source for "Sargonic heroes" in oral tradition in the later Bronze Age is a Middle Hittite (15th century BC) record of a Hurro-Hittite song, which calls upon Sargon and his immediate successors as "deified kings" (dšarrena).

Sargon shared his name with two later Mesopotamian kings. Sargon I was a king of the Old Assyrian period presumably named after Sargon of Akkad. Sargon II was a Neo-Assyrian king named after Sargon of Akkad; it is this king whose name was rendered Sargon in the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah 20:1).

Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus showed great interest in the history of the Sargonid dynasty and even conducted excavations of Sargon's palaces and those of his successors.

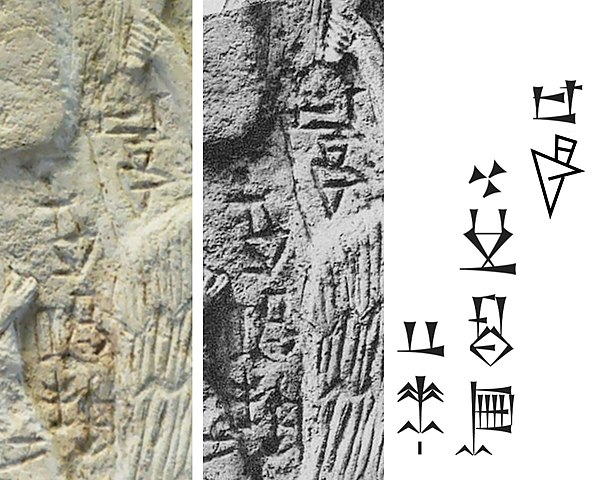

Sargon as Ur-nanshe / Ur-Nina :

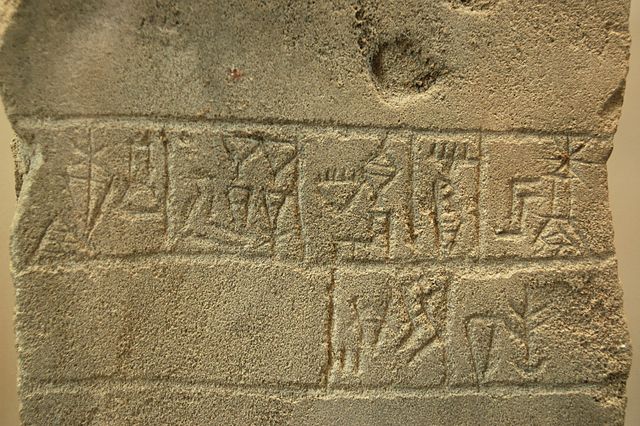

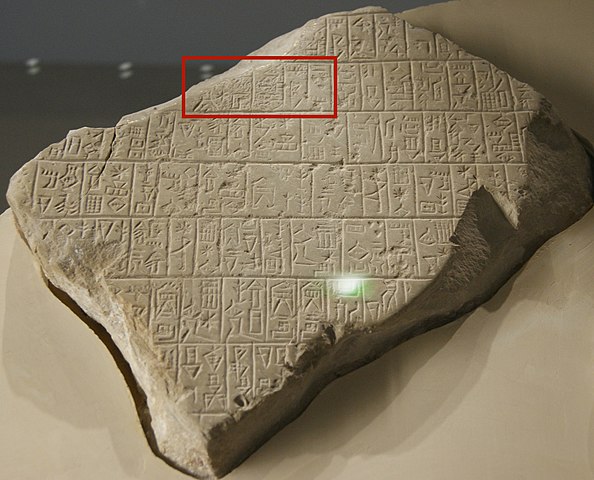

Sargon / Ur-Nanshe / Ur-Nina, seated, wearing flounced skirt. The text to the right of his head reads "Ur-Nanshe" (UR-NAN). The text in front of him reads "Boats from the land of Dilmun carried the wood" (ma2 dilmun kur-ta gu2 giš mu-gal2). Limestone, Early Dynastic III (2550–2500 BC). Found in Telloh (ancient city of Girsu). Louvre Museum.

Reign : c. 2550 BC – 2500 BC

Predecessor : Lugal-sha-engur

Successor : Mudgal / Madgal / Akurgal

Dynasty : 1st Dynasty of Lagash

Father : Gunidu

Ur-Nanshe (Sumerian: UR-NANŠE) also Ur-Nina, was the first king of the First Dynasty of Lagash (approx. 2500 BCE) in the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period III. He is known through inscriptions to have commissioned many buildings projects, including canals and temples, in the state of Lagash, and defending Lagash from its rival state Umma. He was the father of Mudgal / Madgal / Akurgal, who succeeded him, and grandfather of Eanatum. Eanatum expanded the kingdom of Lagash by defeating Umma as illustrated in the Stele of the Vultures and continue building and renovation of Ur-Nanshe's original buildings.

He ascended after Lugalshaengur (lugal-ša-engur), who was the ensi, or high priest of Lagash, and is only known from the macehead inscription of Mesilim.

Temples

:

Inscriptions

:

The Perforated Relief :

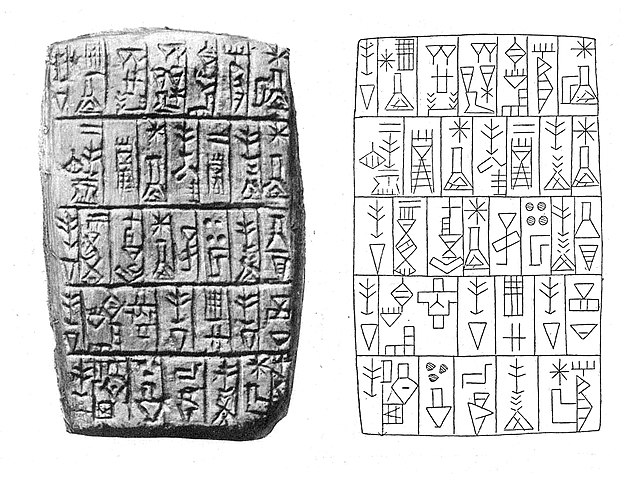

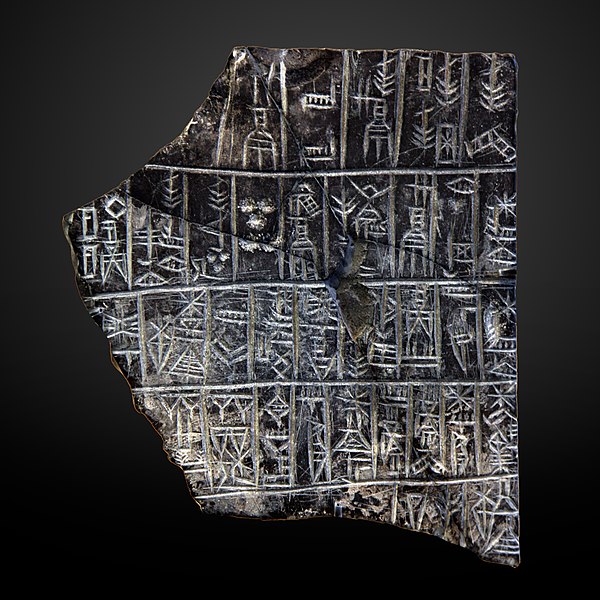

Votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, with his sons and dignitaries. Limestone, Early Dynastic III (2550 – 2500 BC). Found in Telloh (ancient city of Girsu). Louvre Museum

Ur-Nanshe was king of Lagash, circa 2550 BC The Perforated Relief of King Ur-Nanshe is on display at the Louvre. The king is portrayed as a builder of temples and canals, thus a preserver of order perceived to be bestowed upon them by the gods. It is a perforated limestone slab that was probably part of a wall as a votive decoration and is inscribed in Sumerian:

Ur-Nanshe

/ lugal / Lagash / dumu Gunidu / dumu Gurmu/ e2 Ningirsu mu-du3

/ abzu-banda3da mu-du3 / e2 Dnanshe mu-du3

-

Dedication inscription of Ur-Nanshe (top left corner)

In the top register he is dressed in a kaunakes (tufted wool skirt), carrying a basket of bricks on his head while surrounded by other Lagash elite, his wife, and seven of his sons. Inscriptions on their respective garments identify each person. On the bottom register, Ur-Nanshe is at a banquet, which is to celebrate the building of the temple. He is seated on a throne wearing the same outfit as the top register surrounded by other court members. In both registers Ur-Nanshe is shown using hierarchical proportion in which he is considerably larger than everyone surrounding him.

A part of the inscriptions, in front of the seated king, reads: “Boats from the (distant) land of Dilmun carried the wood (for him)”. This is the oldest known written record of Dilmun and importation of goods into Mesopotamia.

The relief at time of discovery

Ur-Nanshe on the relief. He is also depicted wearing a basket for the construction of a temple

Inscription in front of Ur-Nanshe: "The ships of Dilmun, from the foreign lands, brought him wood as a tribute" (ma2 dilmun kur-ta gu2 giš mu-gal2)

Ur-Nanshe's son Akurgal on the relief

Perforated relief of Ur-Nanshe at the Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Very similar to the Louvre's plaque. From Girsu, Iraq Door socket :

Ur-Nanshe door socket with inscription: "Ur-Nanshe, King of Lagash, son of Gunidu, the son of Gurmu..." and a list of the temples he built. Louvre Museum An inscribed door socket from Ur-Nanshe is also known, now in the Louvre Museum. The full inscription of the door socket has been translated as :

"Ur-Nanshe, the king of Lagash, the son of Gunidu, the son of Gurmu, built the house of Ningirsu; built the house of Nanshe; built the house of Gatumdug; built the harem; built the house of Ninmar. The ships of Dilmun brought him wood as a tribute from foreign lands. He built the Ibgal; built the Kinir; built the scepter (?)-house."

- Inscription on the perforated relief of Ur-Nanshe.

The door socket of Ur-Nanshe at time of discovery

"The ships of Dilmun, from the foreign lands, brought him (Ur-Nanshe) wood as a tribute (?)" (ma2 dilmun kur-ta gu2 giš mu-gal2). Door socket of Ur-Nanshe The Plaque of Ur Nanshe :

Plaque of Ur-Nanshe, King of Lagash, with his sons and a cup bearer. Louvre Museum The Plaque of Ur Nanshe is a limestone plaque currently located at the Louvre Museum that honors Ur Nanshe. The figures displayed are the king and his court standing rigid and wide eyed, paying homage to the god Nanshe. They are dressed in kaunakes with their hands clasped together over their chest. Hierarchical scale of the king and the use of cuneiform on the figures to identify them are employed as in the Perforated Relief.

Ur-Nanshe / lugal / Lagash / dumu Gunidu / E-Ningirsu / mudu

- Inscription on the plaque of Ur-Nanshe. Louvre Museum.

Plaque of Ur-Nanshe at time of discovery

Ur-Nanshe himself

Akurgal as a child in the limestone votive relief of Ur-Nanshe Additional inscriptions : Ur-Nanshe inscription

"Ur-Nanshe"

"Lagash"

There are many other inscriptions found by or mentioning Ur-Nanshe. Some of them include a listing of rulers of Lagash and a Hymn to Nashe.

Excerpt from Ruler of Lagash :

“Ur-Nanše, the son of ……, who built the E-Sirara, her temple of happiness and Nigin, her beloved city, acted for 1080 years. Ane-tum, the son of Ur-Nanše”

Excerpt from A Hymn to Nashe :

“There is perfection in the presence of the lady. Lagaš thrives in abundance in the presence of Nanše. She chose the šennu in her holy heart and seated Ur-Nanše, the beloved lord of Lagaš, on the throne. She gave the lofty scepter to the shepherd.”

Tablet of Ur-Nanshe (Urn 24): "Ur-Nanshe, King of Lagash, son of Gunidu, the son of Gurmu, built the house of Nanshe, fashioned (the statue of) Nanshe (...) Boats from the land of Dilmun carried the wood"

"The ships of Dilmun, from the foreign lands, brought him (Ur-Nanshe) wood as a tribute (?)" (ma2 dilmun kur-ta gu2 giš mu-gal2). Tablet of Ur-Nanshe (Urn 24)

Inscription in the name of Ur-Nanshe, an incantation to the reed and to Enki, before the foundation of the Girsu sanctuary for god Ningirsu

Goddess Shul-utul, foundation peg, with inscription "Ur-Nanshe, King of Lagash, son of Gunidu, built the shrine Girsu", probably Girsu, Tell Telloh, Iraq, mid 3rd millennium BCE. Harvard Semitic Museum, Cambridge, MA

"Akurgal king of Lagash, son of Ur-Nanshe" on the Stele of the Vultures

Votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, representing the bird-god Anzû (or Im-dugud) as a lion-headed eagle. Alabaster, Early Dynastic III (2550–2500 BC). Found in Telloh, ancient city of Girsu

Temple foundation figurine in the name of Ur-Nanshe. Inscription "Ur-Nanshe, King of Lagash, has built the shrine of Girsu". British Museum, BM 96565

Stele of Ur-Nanshe with goddess Nisaba, ruler of Lagash, from Lagash, Iraq, 26th century BCE. Iraq Museum

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ur-Nanshe |

_on_his_victory_stele.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

._Cuneiform_text._Early_Dynastic_period,_2550-250.jpg)