| ASSYRIAN PEOPLE Assyrians / Suraye / Suryoye / Atoraye

Ethnic flag used by most Assyrians The Assyrians (Suraye / Suroye) also known as Syriacs / Arameans or Chaldeans are an ethnic group indigenous to the Middle East. [excessive citations] They are speakers of the Neo-Aramaic branch of Semitic languages as well as the primary languages in their countries of residence. Modern Assyrians are Syriac Christians who claim descent from Assyria, one of the oldest civilizations in the world, dating back to 2500 BC in ancient Mesopotamia.

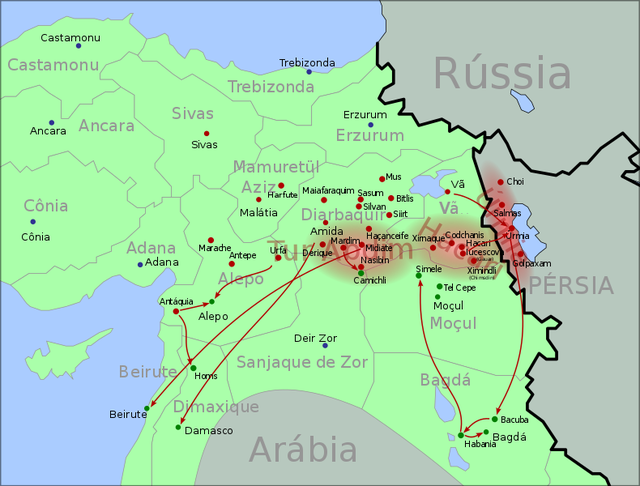

The tribal areas that form the Assyrian homeland are parts of present-day northern Iraq (Nineveh Plains and Dohuk Governorate), southeastern Turkey (Hakkari and Tur Abdin), northwestern Iran (Urmia) and, more recently, northeastern Syria (Al-Hasakah Governorate). The majority have migrated to other regions of the world, including North America, the Levant, Australia, Europe, Russia and the Caucasus during the past century. Emigration was triggered by events such as the massacres of Diyarbakir, the Assyrian genocide (concurrent with the Armenian and Greek genocides) during World War I by the Ottoman Empire and allied Kurdish tribes, the Simele massacre in Iraq in 1933, the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Arab Nationalist Ba'athist policies in Iraq and Syria, the rise of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and its takeover of most of the Nineveh Plains.

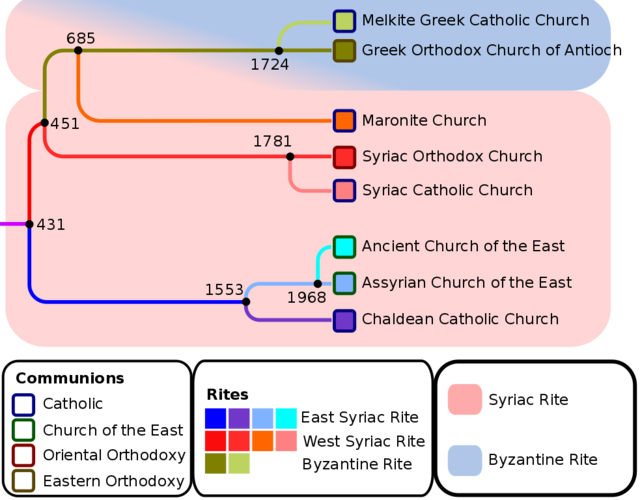

Assyrians are predominantly Christian, mostly adhering to the East and West Syriac liturgical rites of Christianity. The churches that constitute the East Syriac rite include the Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East, and the Ancient Church of the East, whereas the churches of the West Syriac rite are the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church. Both rites use Classical Syriac as their liturgical language.

Most recently, the post-2003 Iraq War and the Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011, have displaced much of the remaining Assyrian community from their homeland as a result of ethnic and religious persecution at the hands of Islamic extremists. Of the one million or more Iraqis reported by the United Nations to have fled Iraq since the occupation, nearly 40% were Assyrians even though Assyrians accounted for only around 3% of the pre-war Iraqi demography.

Because of the emergence of ISIL and the taking over of much of the Assyrian homeland by the terror group, another major wave of Assyrian displacement has taken place. ISIL was driven out from the Assyrian villages in the Khabour River Valley and the areas surrounding the city of Al-Hasakah in Syria by 2015, and from the Nineveh Plains in Iraq by 2017. In northern Syria, Assyrian groups have been taking part both politically and militarily in the Kurdish-dominated but multiethnic Syrian Democratic Forces (see Khabour Guards and Sutoro) and Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.

History

:

Assyria is the homeland of the Assyrian people; it is located in the ancient Near East. In prehistoric times, the region that was to become known as Assyria (and Subartu) was home to Neanderthals such as the remains of those which have been found at the Shanidar Cave. The earliest Neolithic sites in Assyria belonged to the Jarmo culture c. 7100 BC and Tell Hassuna, the centre of the Hassuna culture, c. 6000 BC.

The history of Assyria begins with the formation of the city of Assur perhaps as early as the 25th century BC. The Assyrian king list records kings dating from the 25th century BC onwards, the earliest being Tudiya, who was a contemporary of Ibrium of Ebla. However, many of these early kings would have been local rulers, and from the late 24th century BC to the early 22nd century BC, they were usually subjects of the Akkadian Empire. During the early Bronze Age period, Sargon of Akkad united all the native Semitic-speaking peoples (including the Assyrians) and the Sumerians of Mesopotamia under the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC). The cities of Assur and Nineveh (modern day Mosul), which was the oldest and largest city of the ancient Assyrian Empire, together with a number of other towns and cities, existed as early as the 25th century BC, although they appear to have been Sumerian-ruled administrative centres at this time, rather than independent states. The Sumerians were eventually absorbed into the Akkadian (Assyro-Babylonian) population.

Assyrian soldier of the Achaemenid Army circa 480 BC, Xerxes I tomb, Naqsh-e Rustam In the traditions of the Assyrian Church of the East, they are descended from Abraham's grandson (Dedan son of Jokshan), progenitor of the ancient Assyrians. However, there is no historical basis for the biblical assertion whatsoever; there is no mention in Assyrian records (which date as far back as the 25th century BC). Ashur-uballit I overthrew the Mitanni c. 1365 BC, and the Assyrians benefited from this development by taking control of the eastern portion of Mitanni territory, and later also annexing Hittite, Babylonian, Amorite and Hurrian territories. The Assyrian people, after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 609 BC were under the control of the Neo-Babylonian and later the Persian Empire, which consumed the entire Neo-Babylonian or "Chaldean" Empire in 539 BC. Assyrians became front line soldiers for the Persian Empire under Xerxes I, playing a major role in the Battle of Marathon under Darius I in 490 BC. Herodotus, whose Histories are the main source of information about that battle, makes no mention of Assyrians in connection with it.

Despite the influx of foreign elements, the presence of Assyrians is confirmed by the worship of the god Ashur; references to the name survive into the 3rd century AD. The Greeks, Parthians, and Romans had a rather low level of integration with the local population in Mesopotamia, which allowed their cultures to survive. The kingdoms of Osroene, which inhabitants was mainly a mix of Greeks, Parthians and Arameans, Adiabene, Hatra and Assur, which were under Parthian overlordship, had an Assyrian identity.

Language

:

The Kültepe texts, which were written in Old Assyrian, preserve the earliest known traces of the Hittite language, and the earliest attestation of any Indo-European language, dated to the 20th century BC. Most of the archaeological evidence is typical of Anatolia rather than of Assyria, but the use of both cuneiform and the dialect is the best indication of Assyrian presence. To date, over 20,000 cuneiform tablets have been recovered from the site.

From 1700 BC and onward, the Sumerian language was preserved by the ancient Babylonians and Assyrians only as a liturgical and classical language for religious, artistic and scholarly purposes.

The Akkadian language, with its main dialects Assyrian and Babylonian, once the lingua franca of the Ancient Near East, began to decline during the Neo-Assyrian Empire around the 8th century BC, being marginalized by Old Aramaic during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III. By the Hellenistic period, the language was largely confined to scholars and priests working in temples in Assyria and Babylonia.

Early Christian period :

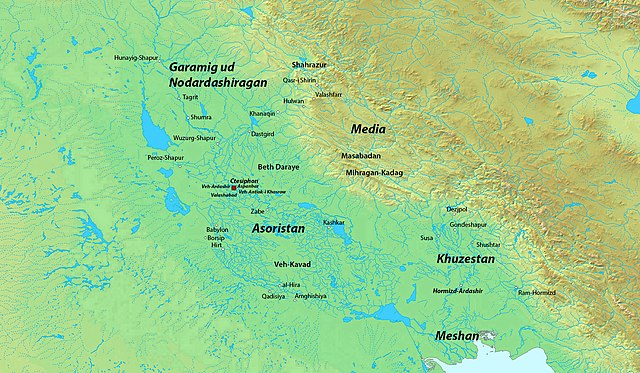

Map of Asoristan (226 – 637 AD) From the 1st century BC, Assyria was the theatre of the protracted Roman–Persian Wars. Much of the region would become the Roman province Assyria from 116 to 118 AD following the conquests of Trajan, but after a Parthian-inspired Assyrian rebellion, the new emperor Hadrian withdrew from the short-lived province Assyria and its neighboring provinces in 118 AD. Following a successful campaign in 197–198, Severus converted the kingdom of Osroene, centred on Edessa, into a frontier Roman province. Roman influence in the area came to an end under Jovian in 363, who abandoned the region after concluding a hasty peace agreement with the Sassanians. From the later 2nd century, the Roman Senate included several notable Assyrians, including Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus and Avidius Cassius.

The Assyrians were Christianized in the first to third centuries in Roman Syria and Roman Assyria. The population of the Sasanian province of Asoristan was a mixed one, composed of Assyrians, Arameans in the far south and the western deserts, and Persians. The Greek element in the cities, still strong during the Parthian Empire, ceased to be ethnically distinct in Sasanian times. The majority of the population were Eastern Aramaic speakers.

Along with the Arameans, Armenians, Greeks, and Nabataeans, the Assyrians were among the first people to convert to Christianity and spread Eastern Christianity to the Far East in spite of becoming, from the 8th century, a minority religion in their homeland following the Muslim conquest of Persia.

In 410, the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sasanian Empire, organized the Christians within that empire into what became known as the Church of the East. Its head was declared to be the bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, who in the acts of the council was referred to as the Grand or Major Metropolitan, and who soon afterward was called the Catholicos of the East. Later, the title of Patriarch was also used. Dioceses were organised into provinces, each of which was under the authority of a metropolitan bishop. Six such provinces were instituted in 410.

A 6th century church, St. John the Arab, in Hakkari, Turkey (Geramon) Another council held in 424 declared that the Catholicos of the East was independent of "western" ecclesiastical authorities (those of the Roman Empire).

Soon afterwards, Christians in the Roman Empire were divided by their attitude regarding the Council of Ephesus (431), which condemned Nestorianism, and the Council of Chalcedon (451), which condemned Monophysitism. Those who for any reason refused to accept one or other of these councils were called Nestorians or Monophysites, while those who accepted both councils, held under the auspices of the Roman emperors, were called Melkites (derived from Syriac malka, king), meaning royalists. All three groups existed among the Syriac Christians, the East Syriacs being called Nestorians and the West Syriacs being divided between the Monophysites (today the Syriac Orthodox Church, also known as Jacobites, after Jacob Baradaeus) and those who accepted both councils (primarily today's Orthodox Church, which has adopted the Byzantine Rite in Greek, but also the Maronite Church, which kept its West Syriac Rite and was not as closely aligned with Constantinople). After this division the West Syriacs, who was under Roman/Byzantine influence and the East Syriacs, under Persian influence, developed dialects that was different from each other, both in pronunciation and written symbolization of vowels. With the rise of Syriac Christianity, eastern Aramaic enjoyed a renaissance as a classical language in the 2nd to 8th centuries, and varieties of that form of Aramaic (Neo-Aramaic languages) are still spoken by a few small groups of Jacobite and Nestorian Christians in the Middle East.

Arab

conquest :

Indigenous Assyrians became second-class citizens (dhimmi) in a greater Arab Islamic state, and those who resisted Arabisation and conversion to Islam were subject to severe religious, ethnic and cultural discrimination, and had certain restrictions imposed upon them. Assyrians were excluded from specific duties and occupations reserved for Muslims, they did not enjoy the same political rights as Muslims, their word was not equal to that of a Muslim in legal and civil matters, as Christians they were subject to payment of a special tax (jizya), they were banned from spreading their religion further or building new churches in Muslim-ruled lands, but were also expected to adhere to the same laws of property, contract and obligation as the Muslim Arabs. They could not seek conversion of a Muslim, a non-Muslim man could not marry a Muslim woman, and the child of such a marriage would be considered Muslim. They could not own a Muslim slave and had to wear different clothing from Muslims in order to be distinguishable. In addition to the jizya tax, they were also required to pay the kharaj tax on their land which was heavier than the jizya. However they were ensured protection, given religious freedom and to govern themselves in accordance to their own laws.

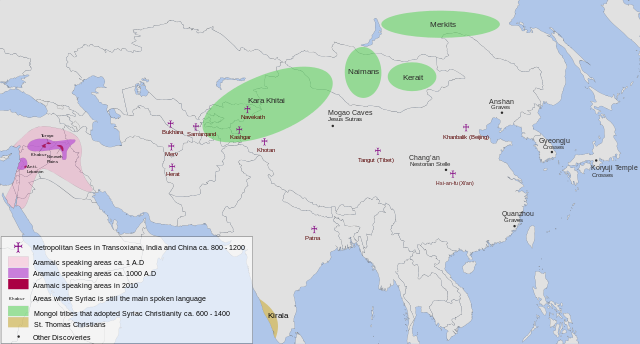

As non-Islamic proselytising was punishable by death under Sharia, the Assyrians were forced into preaching in Transoxiana, Central Asia, India, Mongolia and China where they established numerous churches. The Church of the East was considered to be one of the major Christian powerhouses in the world, alongside Latin Christianity in Europe and the Byzantine Empire.

From the 7th century AD onwards Mesopotamia saw a steady influx of Arabs, Kurds and other Iranian peoples, and later Turkic peoples. Assyrians were increasingly marginalized, persecuted, and gradually became a minority in their own homeland. Conversion to Islam as a result of heavy taxation which also resulted in decreased revenue from their rulers. As a result, the new converts migrated to Muslim garrison towns nearby.

Assyrians remained dominant in Upper Mesopotamia as late as the 14th century, and the city of Assur was still occupied by Assyrians during the Islamic period until the mid-14th century when the Muslim Turco-Mongol ruler Timur conducted a religiously motivated massacre against Assyrians. After, there were no records of Assyrians remaining in Ashur according to the archaeological and numismatic record. From this point, the Assyrian population was dramatically reduced in their homeland.

From the 19th century, after the rise of nationalism in the Balkans, the Ottomans started viewing Assyrians and other Christians in their eastern front as a potential threat. The Kurdish Emirs sought to consolidate their power by attacking Assyrian communities which were already well-established there. Scholars estimate that tens of thousands of Assyrian in the Hakkari region were massacred in 1843 when Bedr Khan Beg, the emir of Bohtan, invaded their region. After a later massacre in 1846, the Ottomans were forced by the western powers into intervening in the region, and the ensuing conflict destroyed the Kurdish emirates and reasserted the Ottoman power in the area. The Assyrians were subject to the massacres of Diyarbakir soon after.

Being culturally, ethnically, and linguistically distinct from their Muslim neighbors in the Middle East—the Arabs, Persians, Kurds, Turks—the Assyrians have endured much hardship throughout their recent history as a result of religious and ethnic persecution by these groups.

Mongolian and Turkic rule :

Aramaic language and Syriac Christianity in the Middle East and Central Asia until being largely annihilated by Tamerlane in the 14th century After initially coming under the control of the Seljuk Empire and the Buyid dynasty, the region eventually came under the control of the Mongol Empire after the fall of Baghdad in 1258. The Mongol khans were sympathetic with Christians and did not harm them. The most prominent among them was probably Isa Kelemechi, a diplomat, astrologer, and head of the Christian affairs in Yuan China. He spent some time in Persia under the Ilkhanate. The 14th century massacres of Timur devastated the Assyrian people. Timur's massacres and pillages of all that was Christian drastically reduced their existence. At the end of the reign of Timur, the Assyrian population had almost been eradicated in many places. Toward the end of the thirteenth century, Bar Hebraeus, the noted Assyrian scholar and hierarch, found "much quietness" in his diocese in Mesopotamia. Syria's diocese, he wrote, was "wasted."[citation needed]

The region was later controlled by the in Iran-based Turkic confederations of the Aq Qoyunlu and Kara Koyunlu. Subsequently, all Assyrians, like with the rest of the ethnicities living in the former Aq Qoyunlu territories, fell into Safavid hands from 1501 and on.

From Iranian Safavid to confirmed Ottoman rule :

The Ottomans secured their control over Mesopotamia and Syria in the first half of the 17th century following the Ottoman–Safavid War (1623–39) and the resulting Treaty of Zuhab. Non-Muslims were organised into millets. Syriac Christians, however, were often considered one millet alongside Armenians until the 19th century, when Nestorian, Syriac Orthodox and Chaldeans gained that right as well.

The Aramaic-speaking Mesopotamian Christians had long been divided between followers of the Church of the East, commonly referred to as "Nestorians", and followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church, commonly called Jacobites. The latter were organised by Marutha of Tikrit (565–649) as 17 dioceses under a "Metropolitan of the East" or "Maphrian", holding the highest rank in the Syriac Orthodox Church after that of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and All the East. The Maphrian resided at Tikrit until 1089, when he moved to the city of Mosul for half a century, before settling in the nearby Monastery of Mar Mattai (still belonging to the Syriac Orthodox Church) and thus not far from the residence of the Eliya line of Patriarchs of the Church of the East. From 1533, the holder of the office was known as the Maphrian of Mosul, to distinguish him from the Maphrian of the Patriarch of Tur Abdin.

In 1552, a group of bishops of the Church of the East from the northern regions of Amid and Salmas, who were dissatisfied with reservation of patriarchal succession to members of a single family, even if the designated successor was little more than a child, elected as a rival patriarch the abbot of the Rabban Hormizd Monastery, Yohannan Sulaqa. This was by no means the first schism in the Church of the East. An example is the attempt to replace Timothy I (779–823) with Ephrem of Gandisabur.

By tradition, a patriarch could be ordained only by someone of archiepiscopal (metropolitan) rank, a rank to which only members of that one family were promoted. For that reason, Sulaqa travelled to Rome, where, presented as the new patriarch elect, he entered communion with the Catholic Church and was ordained by the Pope and recognized as patriarch. The title or description under which he was recognized as patriarch is given variously as "Patriarch of Mosul in Eastern Syria";"Patriarch of the Church of the Chaldeans of Mosul"; "Patriarch of the Chaldeans";"patriarch of Mosul"; or "patriarch of the Eastern Assyrians", this last being the version given by Pietro Strozzi on the second-last unnumbered page before page 1 of his De Dogmatibus Chaldaeorum, of which an English translation is given in Adrian Fortescue's Lesser Eastern Churches.

Mar Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa returned to northern Mesopotamia in the same year and fixed his seat in Amid. Before being imprisoned for four months and then in January 1555 put to death by the governor of Amadiya at the instigation of the rival patriarch of Alqosh, of the Eliya line, he ordained two metropolitans and three other bishops, thus beginning a new ecclesiastical hierarchy: the patriarchal line known as the Shimun line. The area of influence of this patriarchate soon moved from Amid east, fixing the see, after many changes, in the isolated village of Qochanis.

A massacre of Armenians and Assyrians in the city of Adana, Ottoman Empire, April 1909 The Shimun line eventually drifted away from Rome and in 1662 adopted a profession of faith incompatible with that of Rome. Leadership of those who wished communion with Rome passed to the Archbishop of Amid Joseph I, recognized first by the Turkish civil authorities (1677) and then by Rome itself (1681). A century and a half later, in 1830, headship of the Catholics (the Chaldean Catholic Church) was conferred on Yohannan Hormizd, a member of the family that for centuries had provided the patriarchs of the legitimist "Eliya line", who had won over most of the followers of that line. Thus the patriarchal line of those who in 1553 entered communion with Rome are now patriarchs of the "traditionalist" wing of the Church of the East, that which in 1976 officially adopted the name "Assyrian Church of the East".

In the 1840s many of the Assyrians living in the mountains of Hakkari in the south eastern corner of the Ottoman Empire were massacred by the Kurdish emirs of Hakkari and Bohtan.

Another major massacre of Assyrians (and Armenians) in the Ottoman Empire occurred between 1894 and 1897 by Turkish troops and their Kurdish allies during the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The motives for these massacres were an attempt to reassert Pan-Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, resentment at the comparative wealth of the ancient indigenous Christian communities, and a fear that they would attempt to secede from the tottering Ottoman Empire. Assyrians were massacred in Diyarbakir, Hasankeyef, Sivas and other parts of Anatolia, by Sultan Abdul Hamid II. These attacks caused the death of over thousands of Assyrians and the forced "Ottomanisation" of the inhabitants of 245 villages. The Turkish troops looted the remains of the Assyrian settlements and these were later stolen and occupied by Kurds. Unarmed Assyrian women and children were raped, tortured and murdered.

World War I and aftermath :

Assyrian flag, c. 1920

The

burning of bodies of Assyrian women

The Assyrians suffered a number of religiously and ethnically motivated massacres throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, culminating in the large-scale Hamidian massacres of unarmed men, women and children by Muslim Turks and Kurds in the late 19th century at the hands of the Ottoman Empire and its associated (largely Kurdish and Arab) militias, which further greatly reduced numbers, particularly in southeastern Turkey.

The most significant recent persecution against the Assyrian population was the Assyrian genocide which occurred during the First World War. Between 275,000 and 300,000 Assyrians were estimated to have been slaughtered by the armies of the Ottoman Empire and their Kurdish allies, totalling up to two-thirds of the entire Assyrian population.

This led to a large-scale migration of Turkish-based Assyrian people into countries such as Syria, Iran, and Iraq (where they were to suffer further violent assaults at the hands of the Arabs and Kurds), as well as other neighbouring countries in and around the Middle East such as Armenia, Georgia and Russia.

Assyrian volunteers :

Assyrian troops led by Agha Petros (saluting) with a captured Turkish banner in the foreground, 1918 In reaction to the Assyrian Genocide and lured by British and Russian promises of an independent nation, the Assyrians led by Agha Petros and Malik Khoshaba of the Bit-Tyari tribe, fought alongside the Allies against Ottoman forces in an Assyrian war of independence. Despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned the Assyrians fought successfully, scoring a number of victories over the Turks and Kurds. This situation continued until their Russian allies left the war, and Armenian resistance broke, leaving the Assyrians surrounded, isolated and cut off from lines of supply. The sizable Assyrian presence in south eastern Anatolia which had endured for over four millennia was thus reduced to no more than 15,000 by the end of World War I.

Modern history :

Assyrian refugees on a wagon moving to a newly constructed village on the Khabur River in Syria The majority of Assyrians living in what is today modern Turkey were forced to flee to either Syria or Iraq after the Turkish victory during the Turkish War of Independence. In 1932, Assyrians refused to become part of the newly formed state of Iraq and instead demanded their recognition as a nation within a nation. The Assyrian leader Shimun XXI Eshai asked the League of Nations to recognize the right of the Assyrians to govern the area known as the "Assyrian triangle" in northern Iraq. During the French mandate period, some Assyrians, fleeing ethnic cleansings in Iraq during the Simele massacre, established numerous villages along the Khabur River during the 1930s.

The Assyrian Levies were founded by the British in 1928, with ancient Assyrian military rankings such as Rab-shakeh, Rab-talia and Tartan, being revived for the first time in millennia for this force. The Assyrians were prized by the British rulers for their fighting qualities, loyalty, bravery and discipline, and were used to help the British put down insurrections among the Arabs and Kurds. During World War II, eleven Assyrian companies saw action in Palestine and another four served in Cyprus. The Parachute Company was attached to the Royal Marine Commando and were involved in fighting in Albania, Italy and Greece. The Assyrian Levies played a major role in subduing the pro-Nazi Iraqi forces at the battle of Habbaniya in 1941.

However, this cooperation with the British was viewed with suspicion by some leaders of the newly formed Kingdom of Iraq. The tension reached its peak shortly after the formal declaration of independence when hundreds of Assyrian civilians were slaughtered during the Simele massacre by the Iraqi Army in August 1933. The events lead to the expulsion of Shimun XXI Eshai the Catholicos Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East to the United States where resided until his death in 1975.

Celebration at a Syriac Orthodox monastery in Mosul, Ottoman Syria, early 20th century The period from the 1940s through to 1963 saw a period of respite for the Assyrians. The regime of President Abd al-Karim Qasim in particular saw the Assyrians accepted into mainstream society. Many urban Assyrians became successful businessmen, others were well represented in politics and the military, their towns and villages flourished undisturbed, and Assyrians came to excel, and be over represented in sports.

The Ba'ath Party seized power in Iraq and Syria in 1963, introducing laws aimed at suppressing the Assyrian national identity via arabization policies. The giving of traditional Assyrian names was banned and Assyrian schools, political parties, churches and literature were repressed. Assyrians were heavily pressured into identifying as Iraqi/Syrian Christians. Assyrians were not recognized as an ethnic group by the governments and they fostered divisions among Assyrians along religious lines (e.g. Assyrian Church of the East vs. Chaldean Catholic Church vs Syriac Orthodox Church).

In response to Baathist persecution, the Assyrians of the Zowaa movement within the Assyrian Democratic Movement took up armed struggle against the Iraqi government in 1982 under the leadership of Yonadam Kanna, and then joined up with the Iraqi-Kurdistan Front in the early 1990s. Yonadam Kanna in particular was a target of the Saddam Hussein Ba'ath government for many years.

The Anfal campaign of 1986–1989 in Iraq, which was intended to target Kurdish opposition, resulted in 2,000 Assyrians being murdered through its gas campaigns. Over 31 towns and villages, 25 Assyrian monasteries and churches were razed to the ground. Some Assyrians were murdered, others were deported to large cities, and their lands and homes then being appropriated by Arabs and Kurds.

21st century :

Assyrian Genocide Memorial in Yerevan, Armenia Since the 2003 Iraq War social unrest and chaos have resulted in the unprovoked persecution of Assyrians in Iraq mostly by Islamic extremists (both Shia and Sunni) and Kurdish nationalists (ex. Dohuk Riots of 2011 aimed at Assyrians & Yazidis). In places such as Dora, a neighborhood in southwestern Baghdad, the majority of its Assyrian population has either fled abroad or to northern Iraq, or has been murdered. Islamic resentment over the United States' occupation of Iraq, and incidents such as the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons and the Pope Benedict XVI Islam controversy, have resulted in Muslims attacking Assyrian communities. Since the start of the Iraq war, at least 46 churches and monasteries have been bombed.

In recent years, the Assyrians in northern Iraq and northeast Syria have become the target of extreme unprovoked Islamic terrorism. As a result, Assyrians have taken up arms alongside other groups (such as the Kurds, Turcomans and Armenians) in response to unprovoked attacks by Al Qaeda, the Islamic State (ISIL), Nusra Front and other terrorist Islamic Fundamentalist groups. In 2014 Islamic terrorists of ISIL attacked Assyrian towns and villages in the Assyrian Homeland of northern Iraq, together with cities such as Mosul and Kirkuk which have large Assyrian populations. There have been reports of atrocities committed by ISIL terrorists since, including; beheadings, crucifixions, child murders, rape, forced conversions, ethnic cleansing, robbery, and extortion in the form of illegal taxes levied upon non-Muslims. Assyrians in Iraq have responded by forming armed militias to defend their territories.

In response to the Islamic State's invasion of the Assyrian homeland in 2014, many Assyrian organizations also formed their own independent fighting forces to combat ISIL and potentially retake their "ancestral lands." These include the Nineveh Plain Protection Units, Dwekh Nawsha, and the Nineveh Plain Forces. The latter two of these militias were eventually disbanded.

In Syria, the Dawronoye modernization movement has influenced Assyrian identity in the region. The largest proponent of the movement, the Syriac Union Party (SUP) has become a major political actor in the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria. In August 2016, the Ourhi Centre in the city of Zalin was started by the Assyrian community, to educate teachers in order to make Syriac an optional language of instruction in public schools, which then started with the 2016/17 academic year. With that academic year, states the Rojava Education Committee, "three curriculums have replaced the old one, to include teaching in three languages: Kurdish, Arabic and Assyrian." Associated with the SUP is the Syriac Military Council, an Assyrian militia operating in Syria, established in January 2013 to protect and stand up for the national rights of Assyrians in Syria as well as working together with the other communities in Syria to change the current government of Bashar al-Assad. Since 2015 it is a component of the Syrian Democratic Forces. [citation needed] However, many Assyrians and the organizations that represent them, particularly those outside of Syria, are critical of the Dawronoye movement.

A 2018 report stated that Kurdish authorities in Syria, in conjunction with Dawronoye officials, had shut down several Assyrian schools in Northern Syria and fired their administration. This was said to be because these schooled failed to register for a license and for rejecting the new curriculum approved by the Education Authority. Closure methods ranged from officially shutting down schools to having armed men enter the schools and shut them down forcefully. An Assyrian educator named Isa Rashid was later badly beaten outside of his home for rejecting the Kurdish self-administration’s curriculum. The Assyrian Policy Institute claimed that an Assyrian reporter named Souleman Yusph was arrested by Kurdish forces for his reports on the Dawronoye-related school closures in Syria. Specifically, he had shared numerous photographs on Facebook detailing the closures.

Demographics :

Homeland :

Maunsell's map, a Pre-World War I British Ethnographical Map of the Middle East showing "Chaldeans", "Jacobites", and "Nestorians"

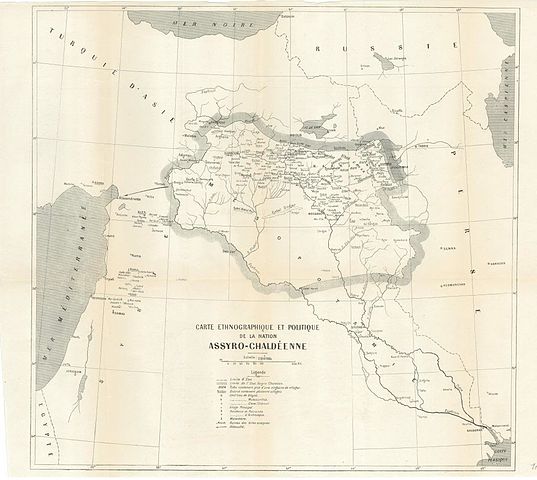

The Assyro-Chaldean Delegation's map of an independent Assyria, presented at the Paris Peace Conference 1919 The Assyrian homeland includes the ancient cities of Nineveh (Mosul), Nuhadra (Dohuk), Arrapha/Beth Garmai (Kirkuk), Al Qosh, Tesqopa and Arbela (Erbil) in Iraq, Urmia in Iran, and Hakkari (a large region which comprises the modern towns of Yuksekova, Hakkâri, Çukurca, Semdinli and Uludere), Edessa/Urhoy (Urfa), Harran, Amida (Diyarbakir) and Tur Abdin (Midyat and Kafro) in Turkey, among others. Some of the cities are presently under Kurdish control and some still have an Assyrian presence, namely those in Iraq, as the Assyrian population in southeastern Turkey (such as those in Hakkari) was ethnically cleansed during the Assyrian genocide of the First World War. Those who survived fled to unaffected areas of Assyrian settlement in northern Iraq, with others settling in Iraqi cities to the south. Though many also immigrated to neighbouring countries in and around the Caucasus and Middle East like Armenia, Syria, Georgia, southern Russia, Lebanon and Jordan.

In ancient times, Akkadian-speaking Assyrians have existed in what is now Syria, Jordan, Israel and Lebanon, among other modern countries, due to the sprawl of the Neo-Assyrian empire in the region. Though recent settlement of Christian Assyrians in Nisabina, Qamishli, Al-Hasakah, Al-Qahtaniyah, Al Darbasiyah, Al-Malikiyah, Amuda, Tel Tamer and a few other small towns in Al-Hasakah Governorate in Syria, occurred in the early 1930s, when they fled from northern Iraq after they were targeted and slaughtered during the Simele massacre. The Assyrians in Syria did not have Syrian citizenship and title to their established land until late the 1940s.

Sizable Assyrian populations only remain in Syria, where an estimated 400,000 Assyrians live, and in Iraq, where an estimated 300,000 Assyrians live. In Iran and Turkey, only small populations remain, with only 20,000 Assyrians in Iran, and a small but growing Assyrian population in Turkey, where 25,000 Assyrians live, mostly in the cities and not the ancient settlements. In Tur Abdin, a traditional center of Assyrian culture, there are only 2,500 Assyrians left. Down from 50,000 in the 1960 census, but up from 1,000 in 1992. This sharp decline is due to an intense conflict between Turkey and the PKK in the 1980s. However, there are an estimated 25,000 Assyrians in all of Turkey, with most living in Istanbul. Most Assyrians currently reside in the West due to the centuries of persecution by the neighboring Muslims. Prior to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, in a 2013 report by a Chaldean Syriac Assyrian Popular Council official, it was estimated that 300,000 Assyrians remained in Iraq.

Assyrian

subgroups :

Map depicting Assyrian relocation after Seyfo in 1914

Persecution :

During the eras of Mongol rule under Genghis Khan and Timur, there was indiscriminate slaughter of tens of thousands of Assyrians and destruction of the Assyrian population of northwestern Iran and central and northern Iran.

More recent persecutions since the 19th century include the massacres of Badr Khan, the massacres of Diyarbakir (1895), the Adana massacre, the Assyrian genocide, the Simele massacre, and the al-Anfal campaign.

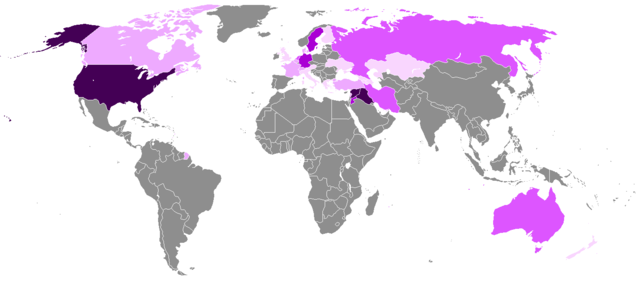

Diaspora :

Assyrian

world population :

more

than 500,000

100,000–500,000

50,000–100,000

10,000–50,000

less

than 10,000

Since the Assyrian genocide, many Assyrians have left the Middle East entirely for a more safe and comfortable life in the countries of the Western world. As a result of this, the Assyrian population in the Middle East has decreased dramatically. As of today there are more Assyrians in the diaspora than in their homeland. The largest Assyrian diaspora communities are found in Sweden (100,000), Germany (100,000), the United States (80,000), and in Australia (46,000).

By ethnic percentage, the largest Assyrian diaspora communities are located in Södertälje in Stockholm County, Sweden, and in Fairfield City in Sydney, Australia, where they are the leading ethnic group in the suburbs of Fairfield, Fairfield Heights, Prairiewood and Greenfield Park. There is also a sizable Assyrian community in Melbourne, Australia (Broadmeadows, Meadow Heights and Craigieburn) In the United States, Assyrians are mostly found in Chicago (Niles and Skokie), Detroit (Sterling Heights, and West Bloomfield Township), Phoenix, Modesto (Stanislaus County) and Turlock.

Furthermore, small Assyrian communities are found in San Diego, Sacramento and Fresno in the United States, Toronto in Canada and also in London, UK (London Borough of Ealing). In Germany, pocket-sized Assyrian communities are scattered throughout Munich, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Berlin and Wiesbaden. In Paris, France, the commune of Sarcelles has a small number of Assyrians. Assyrians in the Netherlands mainly live in the east of the country, in the province of Overijssel. In Russia, small groups of Assyrians mostly reside in Krasnodar Kray and Moscow.

To note, the Assyrians residing in California and Russia tend to be from Iran, whilst those in Chicago and Sydney are predominantly Iraqi Assyrians. More recently, Syrian Assyrians are growing in size in Sydney after a huge influx of new arrivals in 2016, who were granted asylum under the Federal Government's special humanitarian intake. The Assyrians in Detroit are primarily Chaldean speakers, who also originate from Iraq. Assyrians in such European countries as Sweden and Germany would usually be Turoyo-speakers or Western Assyrians.

Identity and subdivisions :

Assyrian flag (adopted in 1968)

Syriac-Aramean flag

Chaldean flag (published in 1999) Syriac christians of the Middle East and diaspora employ different terms for self-identification based on conflicting beliefs in the origin and identity of their respective communities. In certain areas of the Assyrian homeland, identity within a community depends on a person's village of origin (see List of Assyrian settlements) or Christian denomination rather than their ethnic commonality, for instance Chaldean Catholics preferring to be called Chaldeans instead of Assyrians, or a Syriac Orthodox Christian preferring to be called a Syriac-Aramean.

During the 19th century, English archaeologist Austen Henry Layard believed that the native Christian communities in the historical region of Assyria were descended from the ancient Assyrians, a view that was also shared by William Ainger Wigram. Although at the same time Horatio Southgate and George Thomas Bettany claimed during their travels through Mesopotamia that the Syriac christians are the descendants of the Arameans.

Today, Assyrians and other minority ethnic groups in the Middle East, feel pressure to identify as "Arabs","Turks" and "Kurds".

In addition, Western media often makes no mention of any ethnic identity of the Christian people of the region and simply call them Christians, Iraqi Christians, Iranian Christians, Christians in Syria, and Turkish Christians, a label rejected by Assyrians.

Self-designation

:

Assyrian vs. Syrian naming controversy :

Proximity between Roman Syria and Mesopotamia in the 1st century AD (Alain Manesson Mallet, 1683) As early as the 8th century BC Luwian and Cilician subject rulers referred to their Assyrian overlords as Syrian, a western Indo-European corruption of the original term Assyrian. The Greeks used the terms "Syrian" and "Assyrian" interchangeably to indicate the indigenous Arameans, Assyrians and other inhabitants of the Near East, Herodotus considered "Syria" west of the Euphrates. Starting from the 2nd century BC onwards, ancient writers referred to the Seleucid ruler as the King of Syria or King of the Syrians. The Seleucids designated the districts of Seleucis and Coele-Syria explicitly as Syria and ruled the Syrians as indigenous populations residing west of the Euphrates (Aramea) in contrast to Assyrians who had their native homeland in Mesopotamia east of the Euphrates.

This version of the name took hold in the Hellenic lands to the west of the old Assyrian Empire, thus during Greek Seleucid rule from 323 BC the name Assyria was altered to Syria, and this term was also applied to Aramea to the west which had been an Assyrian colony, and from this point the Greeks applied the term without distinction between the Assyrians of Mesopotamia and Arameans of the Levant. When the Seleucids lost control of Assyria to the Parthians they retained the corrupted term (Syria), applying it to ancient Aramea, while the Parthians called Assyria "Assuristan," a Parthian form of the original name. It is from this period that the Syrian vs Assyrian controversy arises.

The question of ethnic identity and self-designation is sometimes connected to the scholarly debate on the etymology of "Syria". The question has a long history of academic controversy, but majority mainstream opinion currently strongly favours that Syria is indeed ultimately derived from the Assyrian term Aššurayu. Meanwhile, some scholars has disclaimed the theory of Syrian being derived from Assyrian as "simply naive", and detracted its importance to the naming conflict.

Rudolf Macuch points out that the Eastern Neo-Aramaic press initially used the term "Syrian" (suryêta) and only much later, with the rise of nationalism, switched to "Assyrian" (atorêta). According to Tsereteli, however, a Georgian equivalent of "Assyrians" appears in ancient Georgian, Armenian and Russian documents. This correlates with the theory of the nations to the East of Mesopotamia knew the group as Assyrians, while to the West, beginning with Greek influence, the group was known as Syrians. Syria being a Greek corruption of Assyria. The debate appears to have been settled by the discovery of the Çineköy inscription in favour of Syria being derived from Assyria.

The Çineköy inscription is a Hieroglyphic Luwian-Phoenician bilingual, uncovered from Çineköy, Adana Province, Turkey (ancient Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BC. Originally published by Tekoglu and Lemaire (2000), it was more recently the subject of a 2006 paper published in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, in which the author, Robert Rollinger, lends support to the age-old debate of the name "Syria" being derived from "Assyria" (see Etymology of Syria).

The object on which the inscription is found is a monument belonging to Urikki, vassal king of Hiyawa (i.e., Cilicia), dating to the eighth century BC. In this monumental inscription, Urikki made reference to the relationship between his kingdom and his Assyrian overlords. The Luwian inscription reads "Sura/i" whereas the Phoenician translation reads ’ŠR or "Ashur" which, according to Rollinger (2006), "settles the problem once and for all".

The modern terminological problem goes back to colonial times, but it became more acute in 1946, when with the independence of Syria, the adjective Syrian referred to an independent state. The controversy isn't restricted to exonyms like English "Assyrian" vs. "Aramaean", but also applies to self-designation in Neo-Aramaic, the minority "Aramaean" faction endorses both Suryaye and Aramaye, while the majority "Assyrian" faction insists on Aturaye but also accepts Suryaye.[citation needed]

Culture :

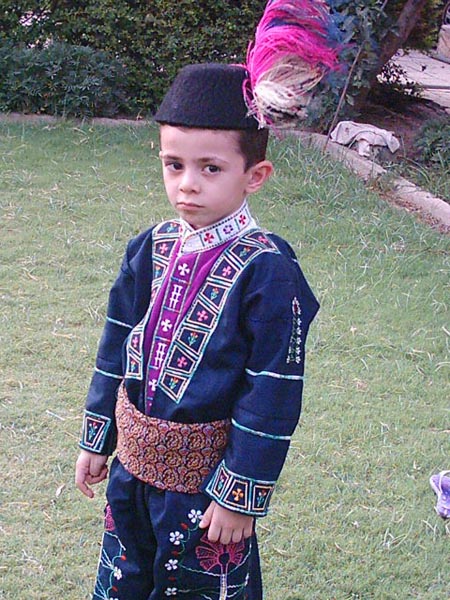

Assyrian child dressed in traditional clothes

Assyrian culture is largely influenced by Christianity. There are

many Assyrian customs that are common in other Middle Eastern cultures.

Main festivals occur during religious holidays such as Easter and

Christmas. There are also secular holidays such as Kha b-Nisan (vernal

equinox).

People often greet and bid relatives farewell with a kiss on each cheek and by saying Shlama/Shlomo lokh, which means: "Peace be upon you" in Neo-Aramaic. Others are greeted with a handshake with the right hand only; according to Middle Eastern customs, the left hand is associated with evil. Similarly, shoes may not be left facing up, one may not have their feet facing anyone directly, whistling at night is thought to waken evil spirits, etc. A parent will often place an eye pendant on their baby to prevent "an evil eye being cast upon it". Spitting on anyone or their belongings is seen as a grave insult.

Assyrians are endogamous, meaning they generally marry within their own ethnic group, although exogamous marriages are not perceived as a taboo, unless the foreigner is of a different religious background, especially a Muslim. Throughout history, relations between the Assyrians and Armenians have tended to be very friendly, as both groups have practised Christianity since ancient times and have suffered through persecution under Muslim rulers. Therefore, mixed marriage between Assyrians and Armenians is quite common, most notably in Iraq, Iran, and as well as in the diaspora with adjacent Armenian and Assyrian communities.

Language :

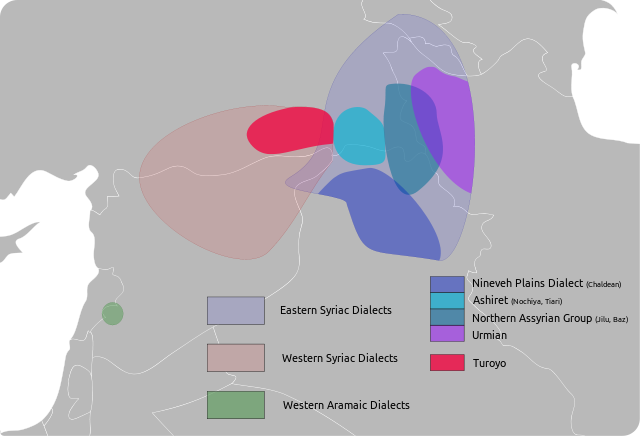

The Assyrian dialects The Neo-Aramaic languages, which are in the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family, ultimately descend from Late Old Eastern Aramaic, the lingua franca in the later phase of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which displaced the East Semitic Assyrian dialect of Akkadian and Sumerian. The Arameans, a semitic people were absorbed into the Assyrian empire after being conquered by them. Ultimately, the Arameans and many other ethnic groups were thought of as Assyrians, and the Aramean language, Aramaic became the official language of Assyria, alongside Akkadian, because Aramaic was easier to write than their original language. Aramaic was the language of commerce, trade and communication and became the vernacular language of Assyria in classical antiquity. By the 1st century AD, Akkadian was extinct, although its influence on contemporary Eastern Neo-Aramaic languages spoken by Assyrians is significant and some loaned vocabulary still survives in these languages to this day.

To the native speaker, "Syriac" is usually called Surayt, Soureth, Suret or a similar regional variant. A wide variety of languages and dialects exist, including Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, and Turoyo. Minority dialects include Senaya and Bohtan Neo-Aramaic, which are both near extinction. All are classified as Neo-Aramaic languages and are written using Syriac script, a derivative of the ancient Aramaic script. Jewish varieties such as Lishanid Noshan, Lishán Didán and Lishana Deni, written in the Hebrew script, are spoken by Assyrian Jews.

There is a considerable amount of mutual intelligibility between Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Senaya, Lishana Deni and Bohtan Neo-Aramaic. Therefore, these "languages" would generally be considered to be dialects of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic rather than separate languages. The Jewish Aramaic languages of Lishan Didan and Lishanid Noshan share a partial intelligibility with these varieties. The mutual intelligibility between the aforementioned languages and Turoyo is, depending on the dialect, limited to partial, and may be asymmetrical.

Being stateless, Assyrians are typically multilingual, speaking both their native language and learning those of the societies they reside in. While many Assyrians have fled from their traditional homeland recently, a substantial number still reside in Arabic-speaking countries speaking Arabic alongside the Neo-Aramaic languages and is also spoken by many Assyrians in the diaspora. The most commonly spoken languages by Assyrians in the diaspora are English, German and Swedish. Historically many Assyrians also spoke Turkish, Armenian, Azeri, Kurdish, and Persian and a smaller number of Assyrians that remain in Iran, Turkey (Istanbul and Tur Abdin) and Armenia still do today. Many loanwords from the aforementioned languages also exist in the Neo-Aramaic languages, with the Iranian languages and Turkish being the greatest influences overall. Only Turkey is reported to be experiencing a population increase of Assyrians in the four countries constituting their historical homeland, largely consisting of Assyrian refugees from Syria and a smaller number of Assyrians returning from the diaspora in Europe.

Script

:

The oldest and classical form of the alphabet is the 'Estrangela script. Although 'Estrangela is no longer used as the main script for writing Syriac, it has received some revival since the 10th century, and it has been added to the Unicode Standard in September, 1999. The East Syriac dialect is usually written in the Madnhaya form of the alphabet, which is often translated as "contemporary", reflecting its use in writing modern Neo-Aramaic. The West Syriac dialect is usually written in the Serta form of the alphabet. Most of the letters are clearly derived from 'Estrangela, but are simplified, flowing lines.

Furthermore, for practical reasons, Assyrian people would also use the Latin alphabet, especially in social media.

Religion :

Historical divisions within Syriac Christian Churches in the Middle East Assyrians belong to various Christian denominations such as the Assyrian Church of the East, with an estimated 400,000 members, the Chaldean Catholic Church, with about 600,000 members, and the Syriac Orthodox Church ('Idto Suryoyto Trisat Šubho), which has between 1 million and 4 million members around the world (only some of whom are Assyrians), the Ancient Church of the East with some 100,000 members. A small minority of Assyrians accepted the Protestant Reformation thus are Reform Orthodox in the 20th century, possibly due to British influences, and is now organized in the Assyrian Evangelical Church, the Assyrian Pentecostal Church and other Protestant/Reform Orthodox Assyrian groups. While there are some atheist Assyrians, they tend to still associate with some denomination.

Many members of the following churches consider themselves Assyrian. Ethnic identities are often deeply intertwined with religion, a legacy of the Ottoman Millet system. The group is traditionally characterized as adhering to various churches of Syriac Christianity and speaking Neo-Aramaic languages. It is subdivided into :

Baptism and First Communion are celebrated extensively, similar to a Brit Milah or Bar Mitzvah in Jewish communities. After a death, a gathering is held three days after burial to celebrate the ascension to heaven of the dead person, as of Jesus; after seven days another gathering commemorates their death. A close family member wears only black clothes for forty days and nights, or sometimes a year, as a sign of mourning.

During the "Seyfo" genocide, there were a number of Assyrians who converted to Islam. They reside in Turkey, and practice Islam but still retain their identity. A small number of Assyrian Jews exist as well.

Music :

Traditional clothing may be worn for Assyrian folk dance Assyrian music is a combination of traditional folk music and western contemporary music genres, namely pop and soft rock, but also electronic dance music. Instruments traditionally used by Assyrians include the zurna and davula, but has expanded to include guitars, pianos, violins, synthesizers (keyboards and electronic drums), and other instruments.

Some well known Assyrian singers in modern times are Ashur Bet Sargis, Sargon Gabriel, Evin Agassi, Janan Sawa, Juliana Jendo, and Linda George. Assyrian artists that traditionally sing in other languages include Melechesh, Timz and Aril Brikha. Assyrian-Australian band Azadoota performs its songs in the Assyrian language whilst using a western style of instrumentation.

The first international Aramaic Music Festival was held in Lebanon in August 2008 for Assyrian people internationally.

Dance :

Folk dance in an Assyrian party in Chicago Assyrians have numerous traditional dances which are performed mostly for special occasions such as weddings. Assyrian dance is a blend of both ancient indigenous and general Near Eastern elements. Assyrian folk dances are mainly made up of circle dances that are performed in a line, which may be straight, curved, or both. The most common form of Assyrian folk dance is khigga, which is routinely danced as the bride and groom are welcomed into the wedding reception. Most of the circle dances allow unlimited number of participants, with the exception of the Sabre Dance, which require three at most. Assyrian dances would vary from weak to strong, depending on the mood and tempo of a song.

Festivals

:

Assyrians celebrate a number of festivals unique to their culture and traditions as well as religious ones :

Assyrians also practice unique marriage ceremonies. The rituals performed during weddings are derived from many different elements from the past 3,000 years. An Assyrian wedding traditionally lasted a week. Today, weddings in the Assyrian homeland usually last 2–3 days; in the Assyrian diaspora they last 1–2 days.

Traditional

clothing :

Cuisine :

Typical Assyrian cuisine Assyrian cuisine is similar to other Middle Eastern cuisines and is rich in grains, meat, potato, cheese, bread and tomatoes. Typically, rice is served with every meal, with a stew poured over it. Tea is a popular drink, and there are several dishes of desserts, snacks, and beverages. Alcoholic drinks such as wine and wheat beer are organically produced and drunk. Assyrian cuisine is primarily identical to Iraqi/Mesopotamian cuisine, as well as being very similar to other Middle Eastern and Caucasian cuisines, as well as Greek cuisine, Levantine cuisine, Turkish cuisine, Iranian cuisine, Israeli cuisine, and Armenian cuisine, with most dishes being similar to the cuisines of the area in which those Assyrians live/originate from. It is rich in grains such as barley, meat, tomato, herbs, spices, cheese, and potato as well as herbs, fermented dairy products, and pickles.

Genetics

:

In a 2006 study of the Y chromosome DNA of six regional Armenian populations, including, for comparison, Assyrians and Syrians, researchers found that, "the Semitic populations (Assyrians and Syrians) are very distinct from each other according to both [comparative] axes. This difference supported also by other methods of comparison points out the weak genetic affinity between the two populations with different historical destinies." A 2008 study on the genetics of "old ethnic groups in Mesopotamia", including 340 subjects from seven ethnic communities ("Assyrian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Armenian, Turkmen, the Arab peoples in Iran, Iraq, and Kuwait") found that Assyrians were homogeneous with respect to all other ethnic groups sampled in the study, regardless of religious affiliation.

In a 2011 study focusing on the genetics of Marsh Arabs of Iraq, researchers identified Y chromosome haplotypes shared by Marsh Arabs, Iraqis, and Assyrians, "supporting a common local background." In a 2017 study focusing on the genetics of Northern Iraqi populations, it was found that Iraqi Assyrians and Iraqi Yazidis clustered together, but away from the other Northern Iraqi populations analyzed in the study, and largely in between the West Asian and Southeastern European populations. According to the study, "contemporary Assyrians and Yazidis from northern Iraq may in fact have a stronger continuity with the original genetic stock of the Mesopotamian people, which possibly provided the basis for the ethnogenesis of various subsequent Near Eastern populations".

Haplogroups

:

Haplogroup J2 has been measured at 13.4%, which is commonly found in the Fertile Crescent, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Italy, coastal Mediterranean, and the Iranian plateau.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)