| ABLE PANCH / PANCHAYAT Ceremonies

& Liturgies :

Types of Ceremonies :

In addition, there are purification ceremonies conducted to purify or cleanse a space or person in order to consecrate a space or prepare a person to partake in a religious ceremony.

Ceremonies of the Outer Circle :

The ceremonies performed in homes or public fires often require temporary fires as part of the ceremony. These fires are the Atash Dadgah - originally the court fire.

Ceremonies Using the Atash Dadgah :

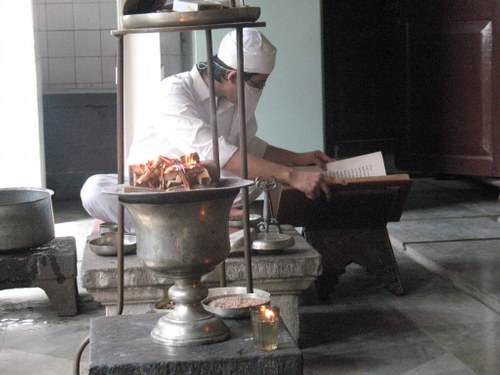

Priest lighting an Atash Dadgah The Atash Dadgah is maintained for the duration of the event on a round metal plate placed on top of an urn. The urn is a scaled down replica of the urns that hold the Atash Bahram or the Atash Adaran. Some enterprising priests cover the plate with metal foil to make clean-up after the event easier. Others cover the metal plate with a thin layer of ash to simulate the ash that would have built up in an urn with a continuously burning fire. If sandalwood is available, small pieces of this wood, or a substitute, are placed over kindling shavings.

Next to the urn is an oil lamp called a devo. The priest uses the devo to set the wood on the urn on fire - and to maintain the fire should it go out during the ceremony. If the devo is constructed from a drinking glass filled with oil on which floats a wick, it is called a glass-na-devo. The attending priest lights the devo using a match. The priest then lights a thin splinter of wood from the devo to ignite the fire in the shavings on the urn. Once the kindling shavings catch fire, the kindling in turn sets the small pieces of wood on fire. A bed of hot coals in the ashes, helps to maintain the fire.

Priest tending to an Atash Dadgah Priests wear white as a symbol of cleanliness and light. They cover their mouths to prevent their breath from reaching the flame. They also sit on a white sheet spread on the floor.

On occasion, the priest ladles powdered incense on the fire. The ladle is called a chamach. The scent of the sandalwood fire and the incense fill the room and give it a traditional atmosphere.

After the ceremony, members of the congregation take turns to come up to the fire, recite a line of prayer, and at times place a small piece of wood on the fire to keep it burning. Some may place their fingers on the rim of the urn and draw the energy of the fire up towards their chests in a sweeping motion. Others may take a pinch of the ashes and rub it once on to their foreheads with their thumb.

When the ceremony is finished, the fire is allowed to extinguish itself and the ashes are disposed.

Priests :

The Afringan's flower ritual Photos in Jashan and Afringan for Beginners by Ervad Yazdi Antia, North American Mobeds Council Currently at Fezana Religious Education

Payvand - Connecting via the clasping of hands. Simultaneously, the Rathvi (Raspi) is in contact with the afarganyu (fire urn) Symbolizing the unity, synergy & harmony of the spiritual & material existences Photos in Jashan and Afringan for Beginners by Ervad Yazdi Antia, North American Mobeds Council Currently at Fezana Religious Education

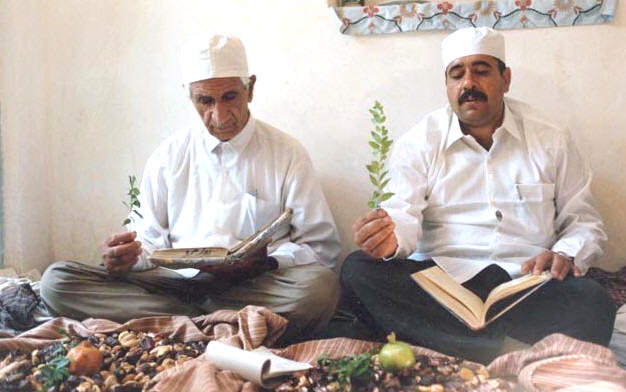

Iranian Priests reciting the Afringan / Afrinameh while holding a sprig during a gahanbar in Yazd, Iran The Afringan ceremony described below and seen in the photographs above and below, can be performed by one or more priests or competent lay persons. If there are two priests officiating, the senior officiator, is called the the Zaoti (or Zoti, cf. Zaotar). The second priest, called the Rathvi (or Raspi), assists and tends to the fire. The ritual utensils and items placed on the tray and sofreh represent the six elements of nature. The priests represents the seventh element, humankind.

Priests with a background from India sit facing one another while Iranian priests sit in a line often in the same line as the people participating in the ceremony.

Setting and Sofreh :

White is the symbol of cleanliness, purity, and goodness.

The utensils used in the ceremony are metal. The include the afarganyu or fire urn, a couple or more metal trays called a sace or ses, a chamach or ladle for placing wood and incense (loban) on the fire, and a chipyo or tongs used to move items.

A jashan/jashne setting and sofreh. Photos in Jashan and Afringan for Beginners by Ervad Yazdi Antia, North American Mobeds Council Currently at Fezana Religious Education

The jashan sace or ses (tray) Photos in Jashan and Afringan for Beginners by Ervad Yazdi Antia, North American Mobeds Council Currently at Fezana Religious Education Symbolism :

The

setting for an Afringan ceremony (also the Jashan / Jashne) using

the Atash Dadgah The jashan / jashne ceremonies of which the Afringan described below is a part, celebrate the coexistent duality of existence: the spiritual and material creations.

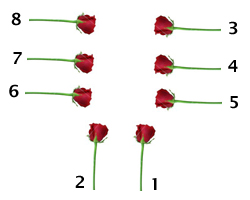

In the diagram and images above, the eight flowers can be seen arranged in the tray or sace that is placed on the sofreh. The two rows represent the spiritual existence, mainyu / mainyva , and gaetha / gaethya, material or physical, existences (in later language: menog and getig). The climactic moment of the ceremony is when the priests pick up and exchange the flowers with the words "athe zamyat" symbolizing the interchange or an interaction between the two realms of existence (for an introduction to the two coexistent realms of existence, see our Overview page). The exchange of flowers which are picked up from the top of one row followed by flowers from the bottom of the other parallel row, also symbolizes the transmigration of righteous souls, the united fravashis of the righteous between the two realms.

The seven aspects of creation and the corresponding Amesha Spentas (divine attributes) together with spenta mainyu, are represented in the setting and items used in the ceremony :

•

The floor or ground represents the earth and the Amesha Spenta Armaiti; The ceremonial tray, the sace, represents as it were, the celestial sphere and all aspects of creation including the spiritual and physical realms.

White

is the symbol of cleanliness, purity, and goodness.

Afringan is also the name of the fire chalice used during the ceremony. The full ceremony consists of three sets of prayers :

1. Atash Nyaish and Doa-Nam Satayashne :

Afringan flower ceremony An Afringan ceremony is also called a flower ceremony as the flowers placed in the sace are held up or, if two or more priests are present, exchanged between the priests during recitation of that part of the Afringan's humatanam prayer (Y35.2). In Iran, when plants are not available, a finger is sometimes held up instead. There the prayers that accompany the holding of the sprigs are called the Afrinameh. Priests from India generally use flowers - at times roses. Priests from Iran generally use myrtle (murd), pomegranate or jujube (red date, or Chinese date) sprigs. The length of the flower or sprig should be a hand span in length.

According to Manekji Hataria's (1813-1890 CE) article on the Religious Ritual Practices of the Iranian Zoroastrians in Zoroastrian Rituals in Context by Michael Stausberg (see link below), the myrtle sprig is dipped in a vessel called 'nava' containing water. "When starting a new karda (section), at the word afrinami / afrinameh, the priest and everyone present picks up a leaf or flower and raises a finger of her or his right hand. Then while reciting upto vispo khatrhem they raise the second finger." The fingers are lowered when reciting the Yatha Ahu Variyo prayer. This process is repeated for every karda.

Flower Order In a full fledged ceremony, eight plants / flowers are used. The eight flowers are arranged in one quadrant of the sace in two parallel rows of three flowers each with the remaining two flowers placed at the end of each row and facing each row. The symbolism is explained above. The Persian Rivayats state that five (symbolizing the five periods or gahs of the day) sprigs / flowers are be used except "when one Dahman is recited", in which case three sprigs / flowers are used.

The choice of Afringan prayers depends of the occasion and often contain a Pazend or Persian portion called a dibache or a preface to the Avestan prayers and a remembrance of the souls of the departed, including great kings of Zoroastrian history, heroes, priests and deceased members of the family sponsoring the Jashan. The dibache is recited in a soft tone. The dibache is recited softly. The Afrin are Pazand prayers of blessing where the priest or person saying the prayers seeks to spread the spiritual strength of the ceremony to all present.

The Afringan ceremony is explained further in avesta.org's page on the subject. After the flower ceremony, the priest touches the different metal vessels with his metal fire-tongs in the four directions of the compass and then again in the directions in-between the four compass points.

3. Doa Tandorosti :

At the end the prayers, the priest may asks the gathering to stand, hold hands and join in prayer. This is an act of solidarity and community. The prayers are usually two ahunavars, and one Ashem Vohu. A fravarane is sometimes added.

Baj Ceremony :

Dron Ceremony :

The ceremony requires the recitation of chapters 3 to 8 of the book of Yasna.

Ceremonies of the Inner Circle :

Yasna Ceremony :

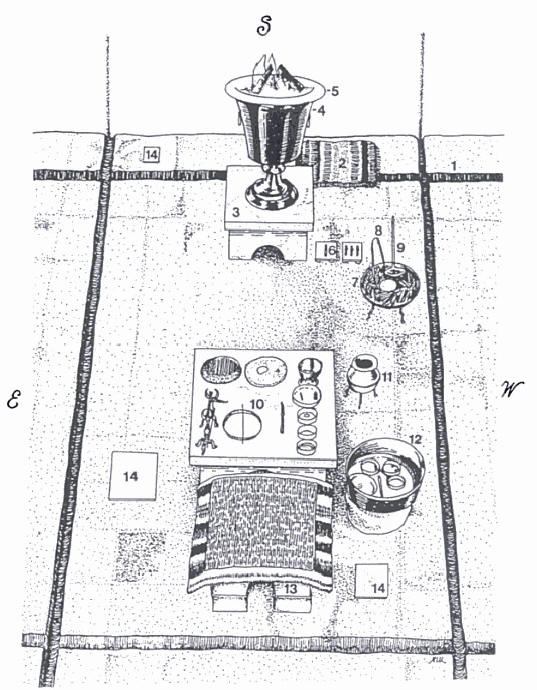

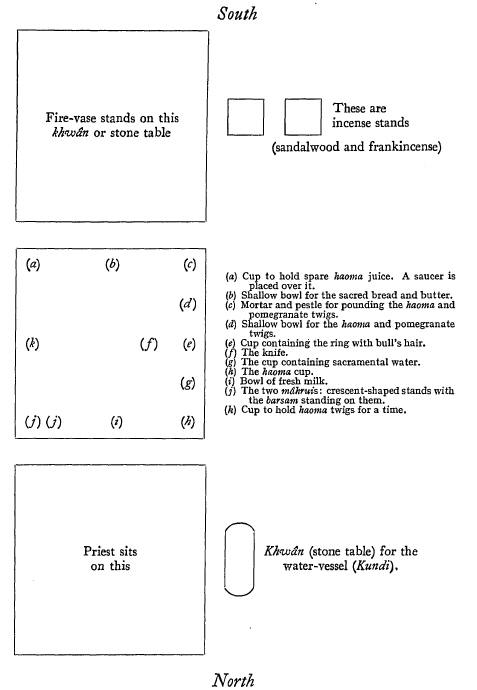

Ritual implements in a fire temple's pavi area Credit: Kotwal/Boyd in Zoroastrian Rituals in Context by Michael Stausberg, page 186

Layout of the pavi area Credit: The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran by E. S. Drower and Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, page 235 Yasna Meaning :

Yasna is commonly taken to mean worship or dedication as well as being related to the words yaz, yezi (Avestan) and later yazishn (Middle Persian), words that evolved yet later into ijeshne and then Jashn / Jashne / Jashan. Given the association of yasna with jashne, a thanksgiving festival, yasna could very well carry a meaning similar to celebration such as honouring or venerating.

In addition, the Avestan yaz is identified with the Sanskrit root word yaj which has been taken to mean worship or to praise. L. H. Mills in his The Zend Avesta: The Sacred Books of the East, Part Thirty-one, Yasna II, page 203, says that the word yas means 'desire to approach' or 'desire the approach of'.

Yazishn-Khana / Gah :

Time or Gah / Geh of the Ceremony :

Novice learning the Yasna ceremony

Preparatory Activities :

In those temple grounds that contain growing date palms and pomegranate (Av. hadanaepata) trees, the priest walks to a date palm with a pot of consecrated water from the well and a sharp knife. After selecting a suitable leaf, the priest washes his hand and carefully cuts the leaf while reciting a manthra. After cutting the leaf, the priest washes the leaf and his hands, and enters the Yasna-gah (see below), the Yasna place, within the temple with the leaf. There he cuts the leaf into three strips and braids the strips into a cord which he uses to ties the baresma (barsom) bundle symbolizing the unity and synergy of the plant world. The ritual collection is repeated for a cutting of a pomegranate twig.

In addition to the pomegranate twigs, pomegranate leaves, date palm strips and consecrated water, sprigs of the ephedra twigs as well as milk (cow's milk in Iran and goat's milk in India) will be used in the preparation of the haoma (hom) extracts (also see ab-zohr below).

Ab-Zohr :

During this rite, two liquid preparations called parahom (from para-haoma) and hom (from haoma) are prepared during different phases of the Yasna ceremony: the first being the Parayagna or Paragna - the pre-yasna phase, and the second being during the yasna ceremony itself. The first preparation is consumed by the senior Zoti priest while a part of the second preparation is poured into the temple's well or a nearby stream in a culmination of the ab-zohr rite. Prof. Mary Boyce translates zaothra as libation - a libation being a liquid that is poured out during a religious ceremony. The remainder of the second extract is consumed by the temple's priests and some of the laity.

Haoma or hom is also the name given to the principle plant, ephedra, used to prepare the parahom and hom extracts. It is also the name given to the entire family of health-giving and healing plants used in conjunction with the ephedra as well as their extracts.

Parahom Preparation Implements / Alat :

The different priestly ceremonial items - the alat

A selection of priestly ceremonial utensils - alat The ritual implements used to produce the hom preparation are part of the priest's ritual implements or alat. They are the mortar (hawan) and pestle (dastag/abar-hawan/labo) for pounding and extracting the juice from the plant, a nine-holed strainer (surakhdar tasjta), and a bowl for holding the parahom.

A priest who knows how to prepare various kinds of haoma extracts and their benefit, is called a hawanan.

The ritual preparation of parahom & hom is described in Mary Boyce's article: Haoma Ritual at CAIS.

Preparation of Parahom Extract During the Parayagna / Paragna

Ceremony :

Then the chopped twigs, leaves and a little consecrated water are repeatedly pounded together during a recitation of Yasna 27. The liquid ground mixture is poured onto the nine-holed strainer and the strained liquid is collected below in a designated bowl. The Raspi collects the twig and leaf residue from the strainer and places the residue close to the fire so that it may dry completely before the end of the ceremony.

Preparation of the Hom Extract During the Yasna Ceremony

:

The Zoti begins to pound the twigs for the second hom preparation between Yasna 22 and 28. While the first preparation had been made using water, milk (cow's milk in Iran and goat's milk in India) is used for the second pressing. The second mixture brings together the beneficial properties of plant life, water and animal milk in order to best promote physical health and healing. Preparing the hom extract during a ritual recitation of the Yasna, enables the mixture to promote spiritual health as well.

The pounding is suspended during Yasnas 29 and 30 and resumed when during Yasnas 31 and 32, the Zoti pounds the mixture three times, straining some of the liquid into one of the bowls after each pounding, each time returning any crushed residue to the mortar. During Yasna 33, the Zoti pours the last of the mortar's contents over the strainer and squeezes the fibrous residue so that it yields its last drops. He removes the fibrous residue from the strainer and places it on a designated spot beside him on the floor. The Raspi picks up the residue and places it beside the fire next to the previous residue from the parahom preparation (in order that this batch may also dry completely). During recital of Yasna 34, the now empty mortar is inverted and the milk-dish is placed the mortar's upturned base. The bowl containing all the squeezed hom extract is set of the top of the milk-dish in a three-tiered arrangement.

The recitation of the Yasnas continues and at Yasna 62, the Raspi feeds the now dried ephedra and pomegranate fibrous residue to the fire.

During the recitation of the remaining Yasnas, the Zoti removes the hom extract container from the top of the three-tiered arrangement and re-rights the upturned mortar. He then pours the extract between two bowls and the mortar thoroughly mixing all the extract and milk, and finishes with all three containing the same amount of of the hom mixture. After the recitation of the final Yasna, 72, both priests carry the hom mixture in the mortar to the temple's well (or a nearby stream) and make a libation by pouring small amounts three times into the well or stream. Small quantities of the remaining hom mixture are consumed by the temple priests and the remainder is available for special needs of the laity such as thanksgiving for a newborn child or administering the last rites to a dying individual. Any remaining hom juice is poured over the roots of trees, especially fruit trees.

Visperad Ceremony :

The Visperad is recited as part of the liturgy used to solemnize Gahambars (seasonal gatherings and feasts) and Nowruz (New Year's Day). The Visperad is always recited with the Yasna.

Vendidad Ceremony :

Because of its length and complexity, the Vendidad portions are frequent read rather than recited from memory.

When the Vendidad is recited on its own and not accompanied with a ritual, the ceremony is known as the Vendidad Sadé.

The Vendidad ceremony is to be performed between nightfall and dawn.

Source :

heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/ |