| SMYRNA

Smyrna, Turkey. Marked in Red dots

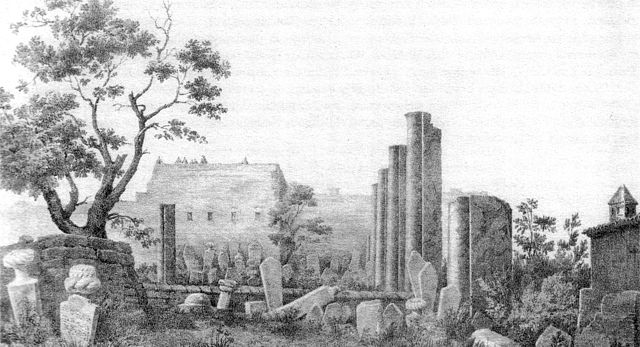

The Agora of Smyrna (columns of the western stoa)

Smyrna among the cities of Ionia and Lydia (ca. 50 AD) Location

: Izmir, Izmir Province, Turkey

Type : Settlement

Smyrna (Romanized: Smýrne, or Smýrna) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defense and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to prominence. The modern name of the city is Izmir.

Two sites of the ancient city are today within Izmir's boundaries. The first site, probably founded by indigenous peoples, rose to prominence during the Archaic Period as one of the principal ancient Greek settlements in western Anatolia. The second, whose foundation is associated with Alexander the Great, reached metropolitan proportions during the period of the Roman Empire. Most of the present-day remains of the ancient city date from the Roman era, the majority from after a 2nd-century AD earthquake. In practical terms, a distinction is often made between these. Old Smyrna was the initial settlement founded around the 11th century BC, first as an Aeolian settlement, and later taken over and developed during the Archaic Period by the Ionians. Smyrna proper was the new city which residents moved to as of the 4th century BC and whose foundation was inspired by Alexander the Great.

Old Smyrna was located on a small peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus at the northeastern corner of the inner Gulf of Izmir, at the edge of a fertile plain and at the foot of Mount Yamanlar. This Anatolian settlement commanded the gulf. Today, the archeological site, named Bayrakli Höyügü, is approximately 700 metres (770 yd) inland, in the Tepekule neighbourhood of Bayrakli. New Smyrna developed simultaneously on the slopes of the Mount Pagos (Kadifekale today) and alongside the coastal strait, immediately below where a small bay existed until the 18th century.

The core of the late Hellenistic and early Roman Smyrna is preserved in the large area of Izmir Agora Open Air Museum at this site. Research is being pursued at the sites of both the old and the new cities. This has been conducted since 1997 for Old Smyrna and since 2002 for the Classical Period city, in collaboration between the Izmir Archaeology Museum and the Metropolitan Municipality of Izmir.

History :

The agora of ancient Smyrna

Etymology :

In inscriptions and coins, the name often was written as Zmýrna, Zmyrnaîos, "of Smyrna".

Arches of the ancient city of Smyrna The name Smyrna may also have been taken from the ancient Greek word for myrrh, smýrna, which was the chief export of the city in ancient times.

Third

millennium to 687 BC :

The early Aeolian Greek settlers of Lesbos and Cyme, expanding eastwards, occupied the valley of Smyrna. It was one of the confederacy of Aeolian city-states, marking the Aeolian frontier with the Ionian colonies.

Strangers or refugees from the Ionian city of Colophon settled in the city. During an uprising in 688 BC, they took control of the city, making it the thirteenth of the Ionian city-states. Revised mythologies said it was a colony of Ephesus. In 688 BC, the Ionian boxer Onomastus of Smyrna won the prize at Olympia, but the coup was probably then a recent event. The Colophonian conquest is mentioned by Mimnermus (before 600 BC), who counts himself equally of Colophon and of Smyrna. The Aeolic form of the name was retained even in the Attic dialect, and the epithet "Aeolian Smyrna" remained current long after the conquest.

Agora of Smyrna, built during the Hellenistic era at the base of Pagos Hill and totally rebuilt under Marcus Aurelius after the destructive 178 AD earthquake Smyrna was located at the mouth of the small river Hermus and at the head of a deep arm of the sea (Smyrnaeus Sinus) that reached far inland. This enabled Greek trading ships to sail into the heart of Lydia, making the city part of an essential trade route between Anatolia and the Aegean. During the 7th century BC, Smyrna rose to power and splendor. One of the great trade routes which cross Anatolia descends the Hermus valley past Sardis, and then, diverging from the valley, passes south of Mount Sipylus and crosses a low pass into the little valley where Smyrna lies between the mountains and the sea. Miletus and later Ephesus were situated at the sea end of the other great trade route across Anatolia; they competed for a time successfully with Smyrna; but after both cities' harbors silted up, Smyrna was without a rival.

The Meles River, which flowed by Smyrna, is famous in literature and was worshiped in the valley. A common and consistent tradition connects Homer with the valley of Smyrna and the banks of the Meles; his figure was one of the stock types on coins of Smyrna, one class of which numismatists call "Homerian." The epithet Melesigenes was applied to him; the cave where he was wont to compose his poems was shown near the source of the river; his temple, the Homereum, stood on its banks. The steady equable flow of the Meles, alike in summer and winter, and its short course, beginning and ending near the city, are celebrated by Aristides and Himerius. The stream rises from abundant springs east of the city and flows into the southeast extremity of the gulf.

The archaic city ("Old Smyrna") contained a temple of Athena from the 7th century BC.

Lydian period :

Head of the poetess Sappho, Smyrna, Marble copy of a prototype belonging to the Hellenistic Period, in Istanbul Archaeology Museums

Map of Smyrna and other cities within the Lydian Empire When the Mermnad kings raised the Lydian power and aggressiveness, Smyrna was one of the first points of attack. Gyges (ca. 687–652 BC) was, however, defeated on the banks of the Hermus, the situation of the battlefield showing that the power of Smyrna extended far to the east. A strong fortress was built probably by the Smyrnaean Ionians to command the valley of Nymphi, the ruins of which are still imposing, on a hill in the pass between Smyrna and Nymphi.

According to Theognis (c. 500 BC), it was pride that destroyed Smyrna. Mimnermus laments the degeneracy of the citizens of his day, who could no longer stem the Lydian advance. Finally, Alyattes (609–560 BC) conquered the city and sacked it, and though Smyrna did not cease to exist, the Greek life and political unity were destroyed, and the polis was reorganized on the village system. Smyrna is mentioned in a fragment of Pindar and in an inscription of 388 BC, but its greatness was past.

Hellenistic period :

This

section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this

section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material

may be challenged and removed. (February 2020)

The statue of the river god Kaystros with a cornucopia in Izmir Museum of History and Art at Kültürpark Smyrna is shut in on the west by a hill now called Deirmen Tepe, with the ruins of a temple on the summit. The walls of Lysimachus crossed the summit of this hill, and the acropolis occupied the top of Pagus. Between the two the road from Ephesus entered the city by the Ephesian gate, near which was a gymnasium. Closer to the acropolis the outline of the stadium is still visible, and the theatre was situated on the north slopes of Pagus. Smyrna possessed two harbours. The outer harbour was simply the open roadstead of the gulf, and the inner was a small basin with a narrow entrance partially filled up by Tamerlane in 1402 AD.

The streets were broad, well paved and laid out at right angles; many were named after temples: the main street, called the Golden, ran across the city from west to east, beginning probably from the temple of Zeus Akraios on the west slope of Pagus, and running round the lower slopes of Pagus (like a necklace on the statue, to use the favorite terms of Aristides the orator) towards Tepecik outside the city on the east, where probably stood the temple of Cybele, worshipped under the name of Meter Sipylene, the patroness of the city. The name is from the nearby Mount Sipylus, which bounds the valley of the city's backlands. The plain towards the sea was too low to be properly drained, and in rainy weather, the streets of the lower town were deep with mud and water.

At the end of the Hellenistic period, in 197 BC, the city suddenly cut its ties with King Eumenes of Pergamum and instead appealed to Rome for help. Because Rome and Smyrna had no ties until then, Smyrna created a cult of Rome to establish a bond, and the cult eventually became widespread through the whole Roman Empire. As of 195 BC, the city of Rome started to be deified, in the cult to the goddess Roma. In this sense, the Smyrneans can be considered as the creators of the goddess Roma.

In 133 BC, when the last Attalid king Attalus III died without an heir, his will conferred his entire kingdom, including Smyrna, to the Romans. They organized it into the Roman province of Asia, making Pergamum the capital. Smyrna, however, as a major seaport, became a leading city in the newly constituted province.

Roman and Byzantine period :

Map of Western Anatolia showing the "Seven Churches of Asia" and the Greek island of Patmos As one of the principal cities of Roman Asia, Smyrna vied with Ephesus and Pergamum for the title "First City of Asia."

A Christian church and a bishopric existed here from a very early time, probably originating in the considerable Jewish colony. It was one of the seven churches addressed in the Book of Revelation. Saint Ignatius of Antioch visited Smyrna and later wrote letters to its bishop, Polycarp. A mob of Jews and pagans abetted the martyrdom of Polycarp in AD 153. Saint Irenaeus, who heard Polycarp as a boy, was probably a native of Smyrna. Another famous resident of the same period was Aelius Aristides.

After a destructive earthquake in 178 AD, Smyrna was rebuilt in the Roman period (2nd century AD) under the emperor Marcus Aurelius. Aelius Aristides wrote a letter to Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus, inviting them to become the new founders of the city. The bust of the emperor's wife Faustina on the second arch of the western stoa confirms this fact.[citation needed]

Polycrates reports a succession of bishops including Polycarp of Smyrna, as well as others in nearby cities such as Melito of Sardis. Related to that time the German historian W. Bauer wrote :

Asian Jewish Christianity received in turn the knowledge that henceforth the "church" would be open without hesitation to the Jewish influence mediated by Christians, coming not only from the apocalyptic traditions, but also from the synagogue with its practices concerning worship, which led to the appropriation of the Jewish passover observance. Even the observance of the sabbath by Christians appears to have found some favor in Asia...we find that in post-apostolic times, in the period of the formation of ecclesiastical structure, the Jewish Christians in these regions come into prominence.

In the late 2nd century, Irenaeus also noted :

Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna…always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true. To these things all the Asiatic Churches testify, as do also those men who have succeeded Polycarp.

Tertullian wrote c. 208 AD :

Anyhow the heresies are at best novelties, and have no continuity with the teaching of Christ. Perhaps some heretics may claim Apostolic antiquity: we reply: Let them publish the origins of their churches and unroll the catalogue of their bishops till now from the Apostles or from some bishop appointed by the Apostles, as the Smyrnaeans count from Polycarp and John, and the Romans from Clement and Peter; let heretics invent something to match this.

Hence, apparently the church in Smyrna was one of the churches that Tertullian felt had real apostolic succession.

During the mid-3rd century, most became affiliated with the Greco-Roman churches.

When Constantinople became the seat of government, the trade between Anatolia and the West diminished in importance, and Smyrna declined.

The Seljuq commander Tzachas seized Smyrna in 1084 and used it as a base for naval raids, but the city was recovered by the general John Doukas.

The city was several times ravaged by the Turks, and had become quite ruinous when the Nicaean emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes rebuilt it about 1222.

Ottoman period :

In the year 1403, Timur had decisively defeated the Knights Hospitaller at Smyrna, and therefore referred to himself as a Ghazi

The Great Fire of Smyrna as seen from an Italian ship, 14 September 1922 Ibn Batuta found it still in great part a ruin when the homonymous chieftain of the Beylik of Aydin had conquered it about 1330 and made his son, Umur, governor. It became the port of the emirate.

During the Smyrniote Crusade in 1344, on October 28, the combined forces of the Knights Hospitaliers of Rhodes, the Republic of Venice, the Papal States and the Kingdom of Cyprus, captured both the harbor and city from the Turks, which they held for nearly 60 years; the citadel fell in 1348, with the death of the governor Umur Baha ad-Din Ghazi.

In 1402, Tamerlane stormed the town and massacred almost all the inhabitants. The Mongol conquest was only temporary, but Smyrna was recovered by the Turks under the Aydin dynasty after which it became Ottoman, when the Ottomans took over the lands of Aydin after 1425.

Greek influence was so strong in the area that the Turks called it "Smyrna of the infidels" (Gavur Izmir). While Turkish sources track the emergence of the term to the 14th century when two separate parts of the city were controlled by two different powers, the upper Izmir being Muslim and the lower part of the city Christian.[citation needed][clarification needed]

During the late 19th and early 20th century, the city was an important financial and cultural center of the Greek world. [citation needed] Out of the 391 factories 322 belonged to local Greeks, while 3 out of the 9 banks were backed by Greek capital. Education was also dominated by the local Greek communities with 67 male and 4 female schools in total. The Ottomans continued to control the area, with the exception of the 1919–1922 period, when the city was assigned to Greece by the Treaty of Sèvres.

The most important Greek educational institution of the region was the Evangelical School that operated from 1733 to 1922.

Post World War I :

Greek troops marching on Izmir's coastal street, May 1919 After the end of the First World War Greece occupied Smyrna from 15 May 1919 and put in place a military administration. The Greek premier Venizelos had plans to annex Smyrna and he seemed to be realizing his objective in the Treaty of Sèvres, signed 10 August 1920. (However, this treaty was not ratified by the parties; the Treaty of Peace of Lausanne replaced it.)

The occupation of Smyrna came to an end when the Turkish army of Kemal Atatürk entered the city on September 9, 1922, at the end of the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). In the immediate aftermath, a fire broke out in the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city on September 13, 1922, known as the Great Fire of Smyrna. The death toll is estimated to range from 10,000 to 100,000.

The Armenians, alongside the Greeks, played a significant role in the city's development, most notably during the age of exploration, where Armenians became a crucial player in the trade sector. The Armenians had trade routes stretching from the far east to Europe. One most notable good the Armenians traded was Iranian silk, where the Shah Abbas of Iran gave them the monopoly over it in the 17th century The Armenians traded Iranian silk with European and Greek merchants in Smyrna; this trade made the Armenians very rich. Besides trade, the Armenians were involved in manufacturing, banking, and other highly productive professions.

After the Armenian Genocide and the Great Fire of Smyrna, the Armenians perished, and the centuries-old history and culture that the Armenians had built in Smyrna were eliminated.

Agora

:

Situated on the northern slopes of the Pagos hills, it was the commercial, judicial and political nucleus of the ancient city, its center for artistic activities and for teaching.

Izmir Agora Open Air Museum consists of five parts, including the agora area, the base of the northern basilica gate, the stoa and the ancient shopping centre.

The agora of Smyrna was built during the Hellenistic era.

Excavations :

Engraving with a view of the site of Smyrna Agora a few years after the first explorations (1843) Although Smyrna was explored by Charles Texier in the 19th century and the German consul in Izmir had purchased the land around the ancient theater in 1917 to start excavations, the first scientific digs can be said to have started in 1927. Most of the discoveries were made by archaeological exploration carried as an extension during the period between 1931 and 1942 by the German archaeologist Rudolf Naumann and Selâhattin Kantar, the director of Izmir and Ephesus museums. They uncovered a three-floor, rectangular compound with stairs in the front, built on columns and arches around a large courtyard in the middle of the building.[citation needed]

New excavations in the agora began in 1996. They have continued since 2002 under the sponsorship of the Metropolitan Municipality of Izmir. A primary school adjacent to the agora that had burned in 1980 was not reconstructed. Instead, its space was incorporated into the historical site. The area of the agora was increased to 16,590 square metres (178,600 sq ft). This permitted the evacuation of a previously unexplored zone. The archaeologists and the local authorities, means permitting, are also keenly eyeing a neighbouring multi-storey car park, which is known to cover an important part of the ancient settlement. [citation needed] During the present renovations the old restorations in concrete are gradually being replaced by marble.

The new excavation has uncovered the agora's northern gate. It has been concluded that embossed figures of the goddess Hestia found in these digs were a continuation of the Zeus altar uncovered during the first digs. Statues of the gods Hermes, Dionysos, Eros and Heracles have also been found, as well as many statues, heads, embossments, figurines and monuments of people and animals, made of marble, stone, bone, glass, metal and terracotta. Inscriptions found here list the people who provided aid to Smyrna after the earthquake of 178 AD.[citation needed]

Economy

:

Toponyms

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smyrna |

.jpg)