| PHOENICIA

Map of Phoenicia and colonies prior to Roman conquest Phoenicia / Put (Phoenician) / Phoiníke (Greek) : 2500 BC – 64 BC

Capital : None; dominant cities were Byblos (2500–1000 BC) and Tyre (900–550 BC)

Common languages : Phoenician, Punic

Religion : Canaanite religion

Demonym(s) : Phoenician

Government : City-states ruled by kings, with varying degrees of oligarchic or plutocratic elements; oligarchic republic in Carthage after c. 480 BC

Well-known kings of Phoenician cities :

• 1800 BC (oldest attested king of Lebanon proper) : Abishemu I

• 969 – 936 BC : Darius III

• 820 – 774 BC : Pygmalion of Tyre

Historical era : Classical antiquity

• Established : 2500 BC

• Tyre becomes dominant city-state under the reign of Hiram I : 969 BC

• Carthage founded (in Roman accounts by Dido) : 814 BC

• Greco-Persian Wars : 499 - 449 BC

• Pompey conquers Phoenicia and rest of Seleucid Empire : 64 BC

Area 1000 BC : 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi)

Preceded by : Canaanites, Hittite Empire and Egyptian Empire

Succeeded by : Achaemenid Phoenicia and Ancient Carthage

Phoenicia was an ancient Semitic-speaking thalassocratic civilization that originated in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. It was concentrated along the coast of Lebanon and included some coastal areas of modern Syria and Galilee, reaching as far north as Arwad, and as far south as Acre and possibly Gaza. At its height between 1100 and 200 BC, Phoenician civilization spread across the Mediterranean, from the Levant to the Iberian Peninsula.

The term Phoenicia is an exonym from ancient Greek that most likely described a dye also known as Tyrian purple, which was a major export of Canaanite port towns. The term did not correspond precisely to Phoenician culture or society as it would have been understood natively; it is debated whether Phoenicians were actually a distinct civilization from the Canaanites and other residents of the Levant. Historian Robert Drews believes the term "Canaanites" corresponds to the ethnic group referred to as "Phoenicians" by the ancient Greeks.

The Phoenicians came to prominence in the mid 12th century BC following the decline of most major cultures in the Late Bronze Age collapse. They developed an expansive maritime trade network that lasted over a millennium, becoming the dominant commercial power for much of classical antiquity. Phoenician trade also helped facilitate the exchange of cultures, ideas, and knowledge between major cradles of civilization such as Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. After its zenith in the ninth century BC, Phoenician civilization in the eastern Mediterranean slowly declined in the face of foreign influence and conquest; its presence would remain in the central and western Mediterranean until the mid second century BC.

The Phoenicians were organized in city-states, similar to those of ancient Greece, of which the most notable were Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. Each city-state was politically independent, and there is no evidence the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single nationality. Carthage, a Phoenician settlement in northwest Africa, became a major civilization in its own right in the seventh century BC.

Though the Phoenicians were long considered a lost civilization due to the lack of indigenous written records, academic and archaeological developments since the mid-20th century have revealed a complex and influential civilization. Their best known legacy is the world's oldest verified alphabet, which they transmitted across the Mediterranean world. The Phoenicians are also credited with innovations in shipbuilding, navigation, industry, agriculture, and government. Their international trade network is believed to have fostered the economic, political, and cultural foundations of Classical Western civilization.

Etymology

:

History

:

Origins

:

Some scholars suggest there is evidence for a Semitic dispersal to the fertile crescent circa 2500 BC; others believe the Phoenicians originated from an admixture of previous non-Semitic inhabitants with the Semitic arrivals. Herodotus believed that the Phoenicians originated from Bahrain, a view shared centuries later by the historian Strabo. The people of modern Tyre in Lebanon, have particularly long maintained Persian Gulf origins. The Dilmun civilization thrived in Bahrain during the period 2200–1600 BC, as shown by excavations of settlements and the Dilmun burial mounds. However, recent genetic researches have shown that present-day Lebanese derive most of their ancestry from a Canaanite-related population.

Emergence

during the Late Bronze Age (1550 - 1200 BC) :

By the mid 14th century, the Phoenician city states were considered "favored cities" to the Egyptians. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and Byblos were regarded as the most important. The Phoenicians had considerable autonomy and their cities were fairly well developed and prosperous. Byblos was evidently the leading city outside Egypt proper; it was a major center of bronze-making, and the primary terminus of precious goods such as tin and lapis lazuli from as far east as Afghanistan. Sidon and Tyre also commanded interest among Egyptian officials, beginning a pattern of rivalry that would span the next millennium.

The Amarna letters report that from 1350 to 1300 BC, neighboring Amorites and Hittites were capturing Phoenician cities, especially in the north. Egypt subsequently lost its coastal holdings from Ugarit in northern Syria to Byblos near central Lebanon.

Ascendance

and high point (1200 - 800 BC) :

The recovery of the Mediterranean economy can be credited to Phoenician mariners and merchants, who re-established long distance trade between Egypt and Mesopotamia in the 10th century BC.

Early into the Iron Age, the Phoenicians established ports, warehouses, markets, and settlement all across the Mediterranean and up to the southern Black Sea. Colonies were established on Cyprus, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Sicily, and Malta, as well as the coasts of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. Phoenician hacksilver dated to this period bears lead isotope ratios matching ores in Sardinia and Spain, indicating the extent of Phoenician trade networks.

By the tenth century BC, Tyre rose to become the richest and most powerful Phoenician city state, particularly during the reign of Hiram I (c. 969–936 BC). During the rule of the priest Ithobaal (887–856 BC), Tyre expanded its territory as far north as Beirut (incorporating its former rival Sidon) and into part of Cyprus; this unusual act of aggression was the closest the Phoenicians ever came to forming a unitary territorial state. Once his realm reached its greatest territorial extent, Ithobaal declared himself "King of the Sidonians", a title that would be used by his successors and mentioned in both Greek and Jewish accounts.

The Late Iron Age saw the height of Phoenician shipping, mercantile, and cultural activity, particularly between 750 and 650 BC. Phoenician influence was visible in the "Orientalization" of Greek cultural and artistic conventions. Among their most popular goods were fine textiles, typically dyed with Tyrian purple. Homer's Iliad, which was composed during this period, references the quality of Phoenician clothing and metal goods.

Foundation

of Carthage :

Vassalage under the Assyrians & Babylonians (858 - 538 BC) :

As a mercantile power concentrated along a narrow coastal strip of land, the Phoenicians lacked the size and population to support a large military. Thus, as neighboring empires began to rise, the Phoenicians increasingly fell under the sway of foreign rulers, who to varying degrees circumscribed their autonomy.

The Assyrian conquest of Phoenicia began with King Shalmaneser III, who rose to power in 858 BC and began a series of campaigns against neighboring states. The Phoenician city-states fell under his rule, forced to pay heavy tribute in money, goods, and natural resources. Initially they were not annexed outright—they remained in a state of vassalage, subordinate to the Assyrians but allowed a certain degree of freedom. This changed in 744 BC with the ascension of Tiglath-Pileser III. By 738 BC, most of the Levant, including northern Phoenicia, were annexed; only Tyre and Byblos, the most powerful of the city states, remained as tributary states outside of direct Assyrian control.

Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon all rebelled against Assyrian rule. In 721 BC, Sargon II besieged Tyre and crushed the rebellion. His successor Sennacherib suppressed further rebellions across the region. During the seventh century BC, Sidon rebelled and was completely destroyed by Esarhaddon, who enslaved its inhabitants and built a new city on its ruins. By the end of the century, the Assyrians had been weakened by successive revolts, which led to their destruction by the Median Empire.

The Babylonians, formerly vassals of the Assyrians, took advantage of the empire's collapse and rebelled, quickly establishing the Neo-Babylonian Empire in its place. Phoenician cities revolted several times throughout the reigns of the first Babylonian king, Nabopolassar (626–605 BC), and his son Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 605–c. 562 BC). In 587 BC Nebuchadnezzar besieged Tyre, which resisted for thirteen years, but ultimately capitulated under "favorable terms".

Persian period (539 - 332 BC) :

In 539 BC, Cyrus the Great, king and founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, took Babylon. As Cyrus began consolidating territories across the Near East, the Phoenicians apparently made the pragmatic calculation of "[yielding] themselves to the Persians." Most of the Levant was consolidated by Cyrus into a single satrapy (province) and forced to pay a yearly tribute of 350 talents, which was roughly half the tribute that was required of Egypt and Libya.

The Phoenician area was later divided into four vassal kingdoms—Sidon, Tyre, Arwad and Byblos—which were allowed considerable autonomy. Unlike in other areas of the empire, there is no record of Persian administrators governing the Phoenician city-states. Local Phoenician kings were allowed to remain in power and even given the same rights as Persian satraps (governors), such as hereditary offices and minting their own coins.

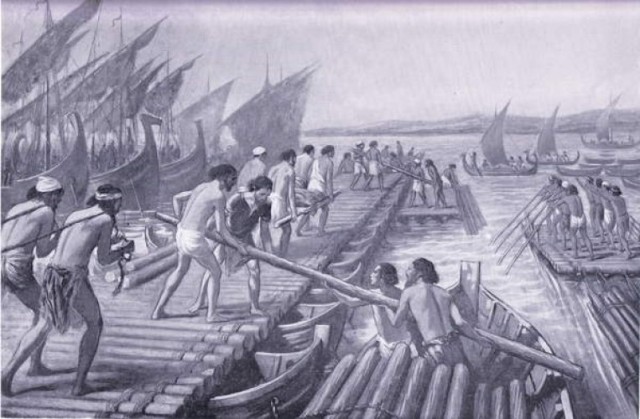

Coin of Abdashtart I of Sidon during the Achaemenid period. He is depicted behind the Persian king on the chariot The Phoenicians remained a core asset to the Achaemenid Empire, particularly for their prowess in maritime technology and navigation; they furnished the bulk of the Persian fleet during the Greco-Persian Wars of the late fifth century BC. Phoenicians under Xerxes I built the Xerxes Canal and the pontoon bridges that allowed his forces to cross into mainland Greece. Nevertheless, they were harshly punished by the Persian king following his defeat at the Battle of Salamis, which he blamed on Phoenician cowardice and incompetence.

In the mid fourth century BC, King Tennes of Sidon led a failed rebellion against Artaxerxes III, enlisting the help of the Egyptians, who were subsequently drawn into a war with the Persians. The resulting destruction of Sidon led to the resurgence of Tyre, which remained the principal Phoenician city for two decades until the arrival of Alexander the Great.

Hellenistic

period (332 - 152 BC) :

A naval action during Alexander the Great's Siege of Tyre (332 BC). Drawing by André Castaigne, 1888 – 89 Alexander's empire had a policy of Hellenization, whereby Hellenic culture, religion, and sometimes language were spread or imposed across conquered peoples, but most of the time Hellenisation was not enforced and was just a language of administration until his death. This was typically implemented through the founding of new cities, the settlement of a Macedonian or Greek urban elite, and the alteration of native place names to Greek. However, there was evidently no organized Hellenization in Phoenicia, and with one or two minor exceptions, all Phoenician city states retained their native names, while Greek settlement and administration appears to have been very limited.

The Phoenicians maintained cultural and commercial links with their western counterparts. Polybius recounts how the Seleucid king Demetrius I escaped from Rome by boarding a Carthaginian ship that was delivering goods to Tyre. The adaptation to Macedonian rule was likely aided by the Phoenicians' historical ties with the Greeks, with whom they shared some mythological stories and figures; the two peoples were even sometimes considered "relatives".

When Alexander's empire collapsed after his death in 323 BC, the Phoenicians came under the control of the largest of its successors, the Seleucids. The Phoenician homeland was repeatedly contested by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt during the forty year Syrian Wars, coming under Ptolemaic rule in the third century BC. The Seleucids reclaimed the area the following century, holding it until the mid-first 2nd century BC. Under their rule, the Phoenicians were evidently allowed a considerable degree of autonomy and self governance.

During the Seleucid Dynastic Wars (157–63 BC), the Phoenician cities were mostly self governed and many of them were fought for or over by the warring factions of the Seleucid royal family. Some Phoenician regions were under the control and influence of the Jews who revolted and succeeded in defeating Seleucids in 164 BC.

The Seleucid Kingdom, including Phoenicia, was seized by Tigranes the Great of Armenia in 82 BC thus ending once and for all the Hellenistic influence on the region.

With their strategically valuable buffer state absorbed into a rival power, the Romans were moved to intervene and conquer the territory in 62 BC. Shortly thereafter, the territory was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria. Phoenicia became a separate province in the third century AD. With the Roman invasion whatever political autonomy Phoenicians had was dissolved and the region was romanised. Roman Empire ruled the province up to 640s when the Muslim Arabs invaded successfully the region and a process of Islamisation and Arabisation started.[citation needed]

Demographics

:

One 2018 study of mitochondrial lineages in Sardinia concluded that the Phoenicians were "inclusive, multicultural and featured significant female mobility", with evidence of indigenous Sardinians integrating "peacefully and permanently" with Semitic Phoenician settlers. The study also found evidence suggesting that south Europeans may have settled in the area of modern Lebanon.

Genetic

studies :

In 2016, the skeleton of 2,500 year old Carthaginian man excavated from a Punic tomb in Tunisia was found bearing the rare U5b2c1 maternal haplogroup. The lineage of this "Young Man of Byrsa" is believed to represent early gene flow from Iberia to the Maghreb.

According to a 2017 study published by the American Journal of Human Genetics, present-day Lebanese derive most of their ancestry from a Canaanite-related population, which therefore implies substantial genetic continuity in the Levant since at least the Bronze Age. More specifically, according to geneticist Chris Tyler-Smith and his team at the Sanger Institute in Britain, who compared "sampled ancient DNA from five Canaanite people who lived 3,750 and 3,650 years ago" to modern people, revealed that 93 percent of the genetic ancestry of people in Lebanon came from the Canaanites (the other 7 percent was of a Eurasian steppe population).

In a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, researchers have shown that there is substantial genetic continuity in Lebanon since the Bronze Age interrupted by three significant admixture events during the Iron Age, Hellenistic, and Ottoman period, each contributing 3–11 percent of non-local ancestry to the admixed population.

Economy

:

Major Phoenician trade networks (c. 1200 – 800 BC) The Phoenicians served as intermediaries between the disparate civilizations that spanned the Mediterranean and Near East, facilitating the exchange of not only goods, but knowledge, culture, and religious traditions. Their expansive and enduring trade network is credited with laying the foundations of an economically and culturally cohesive Mediterranean, which would be continued by the Greeks and especially the Romans.

Phoenician ties with the Greeks ran deep. The earliest verified relationship appears to have begun with the Minoan civilization on Crete (1950–1450 BC), which together with the Mycenaean civilization (1600–1100 BC) is considered the progenitor of classical Greece. Archaeological research suggests that the Minoans gradually imported Near Eastern goods, artistic styles, and customs from other cultures via the Phoenicians.

To Egypt the Phoenicians sold logs of cedar for significant sums, and wine beginning in the eighth century. The wine trade with Egypt is vividly documented by shipwrecks discovered in 1997 in the open sea 50 kilometres (30 mi) west of Ascalon, Palestine. Pottery kilns at Tyre and Sarepta produced the large terracotta jars used for transporting wine. From Egypt, the Phoenicians bought Nubian gold.

Phoenician sarcophagi found in Cádiz, Spain, thought to have been imported from the Phoenician homeland around Sidon. Archaeological Museum of Cádiz From elsewhere, they obtained other materials, perhaps the most important being silver, mostly from Sardinia and the Iberian Peninsula. Tin for making bronze "may have been acquired from Galicia by way of the Atlantic coast or southern Spain; alternatively, it may have come from northern Europe (Cornwall or Brittany) via the Rhone valley and coastal Massalia". Strabo states that there was a highly lucrative Phoenician trade with Britain for tin via the Cassiterides, whose location is unknown but may have been off the northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula.

Industry :

Phoenician

bowl with hunting scene (eighth century BC). The clothing and hairstyle

of the figures is Egyptian, while the subject matter of the central

scene conforms with the Mesopotamian theme of combat between man

and beast. Phoenician artisans frequently adapted the styles of

neighboring cultures.

The Phoenicians were early pioneers in mass production, and sold a variety of items in bulk. They became the leading source of glassware in antiquity, shipping thousands of flasks, beads, and other glass objects across the Mediterranean. Excavations of colonies in Spain suggest they also utilized the potter's wheel. Their exposure to a wide variety of cultures allowed them to manufacture goods for specific markets. The Iliad suggests Phoenician clothing and metal goods were highly prized by the Greeks. Specialized goods were designed specifically for wealthier clientele, including ivory reliefs and plaques, carved clam shells, sculpted amber, and finely detailed and painted ostrich eggs.

Tyrian purple :

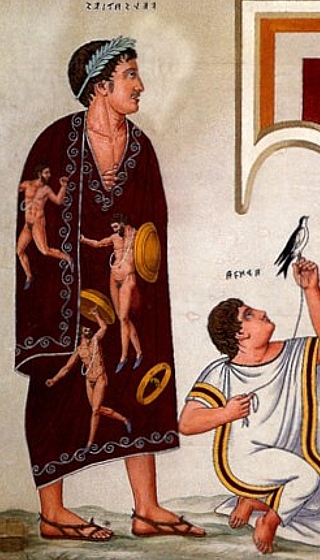

An Etruscan tomb (c. 350 BC) depicting a man wearing in an all-purple toga picta The most prized Phoenician goods were fabrics dyed with Tyrian purple, which formed a major part of Phoenician wealth. The violet-purple dye derived from the hypobranchial gland of the Murex marine snail, once profusely available in coastal waters of the eastern Mediterranean Sea but exploited to local extinction. Phoenicians may have discovered the dye as early as 1750 BC. The Phoenicians established a second production center for the dye in Mogador, in present-day Morocco.

The Phoenicians' exclusive command over the production and trade of the dye, combined with the labor-intensive extraction process, made it very expensive. Tyrian purple subsequently became associated with the upper classes and soon became a status symbol in several civilizations, most notably among the Romans. Assyrian records of tribute from the Phoenicians include "garments of brightly colored stuff" that most likely included Tyrian purple. While the designs, ornamentation, and embroidery used in Phoenician textiles were apparently well-regarded, the techniques and specific descriptions are unknown.

Mining

:

Viticulture

:

The Phoenicians established vineyards and wineries in their colonies in North Africa, Sicily, France, and Spain, and may have taught winemaking to some of their trading partners. The ancient Iberians began producing wine from local grape varieties following their encounter with the Phoenicians, and Iberian cultivars subsequently formed the basis of most western European wine.

Shipbuilding

:

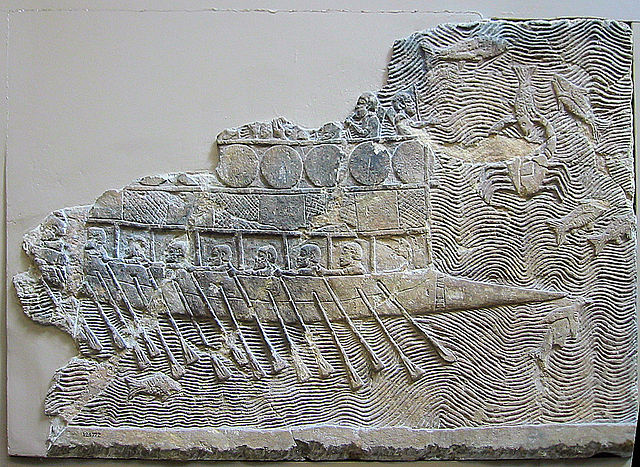

The Phoenicians were possibly the first to introduce the bireme, around 700 BC. An Assyrian account describes Phoenicians evading capture with these ships. [citation needed] The Phoenicians are also credited with inventing the trireme, which was regarded as the most advanced and powerful vessel in the ancient Mediterranean world, and were eventually adopted by the Greeks.

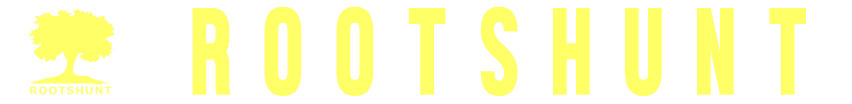

Two Assyrian representations of ships, which could represent Phoenician vessels

Warship with two rows of oars, in a relief from Nineveh (c. 700 BC)

The Timber Transportation relief at the Louvre The Phoenicians developed several other maritime inventions. The amphora, a type of container used for both dry and liquid goods, was an ancient Phoenician invention that became a standardized measurement of volume for close to two thousand years. The remnants of self-cleaning artificial harbors have been discovered in Sidon, Tyre, Atlit, and Acre. The first example of admiralty law also appears in the Levant. The Phoenicians continued to contribute to cartography into the Iron Age.

In 2014, a roughly 50-foot Phoenician trading ship was found near Gozo island in Malta. Dated 700 BC, it is one of the oldest wrecks found in the Mediterranean. Fifty amphorae, used to contain wine and oil, were scattered nearby.

Important cities and colonies :

Map of Phoenician (in yellow) and Greek colonies around 8th to 6th century BC (with German legend) The Phoenicians were not a nation in the political sense, but were organized into independent city states that shared a common language and culture. The leading city states were Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. Rivalries were common, but armed conflict rare.

Numerous other cities existed in the Levant alone, many probably unknown, including Berut (modern Beirut) Ampi, Amia, Arqa, Baalbek, Botrys, Sarepta and Tripoli. From the late tenth century BC, the Phoenicians established commercial outposts throughout the Mediterranean, with Tyre founding colonies in Cyprus, Sardinia, Iberia, the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Malta, and North Africa. Later colonies were established beyond the Straits of Gibraltar, particularly on the Atlantic coast of Iberia, and the Phoenicians may have explored the Canary Islands and the British Isles. Phoenician settlement was especially concentrated in Cyprus, Sicily, Sardinia, Malta, northwest Africa, the Balearic Islands, and southern Iberia.

Phoenician

colonization :

The earliest Phoenician settlements outside the Levant were on Cyprus and Crete, gradually moving westward towards Corsica, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, and Sicily, as well as on the European mainland in Genoa and Marseilles. The first Phoenician colonies in the western Mediterranean were along the northwest African coast and on Sicily, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands. Tyre led the way in settling or controlling coastal areas.

Phoenician colonies were fairly autonomous. At most, they were expected to send annual tribute to their mother city, usually in the context of a religious offering. However, in the seventh century BC the western colonies came under the control of Carthage, which was exercised directly through appointed magistrates. Carthage continued to send annual tribute to Tyre for some time after its independence.

Society

and culture :

Politics and government :

Tomb of King Hiram I of Tyre, located in the village of Hanawai (Hanawiya or Hanawey) in southern Lebanon The Phoenician city-states were fiercely independent in both domestic and foreign affairs. [citation needed] Formal alliances between city states were rare. The relative power and influence of city-states varied over time. Sidon was dominant between the 12th and 11th centuries BC, and exercised some influence over its neighbors, but by the tenth century BC, Tyre rose to become the most powerful city.

Phoenician

society was highly stratified and predominantly monarchical, at

least in its earlier stages. Hereditary kings usually governed with

absolute power over civic, commercial, and religious affairs. They

often relied upon senior officials from the noble and merchant classes;

the priesthood was a distinct class, usually of royal lineage or

from leading merchant families. The king was considered a representative

of the gods and carried many obligations and duties with respect

to religious processions and rituals. Priests were thus highly influential

and often became intertwined with the royal family.

Starting as early as 15th century BC, Phoenician leaders were "advised by councils or assemblies which gradually took greater power". In the sixth century BC, during the period of Babylonian rule, Tyre briefly adopted a system of government consisting of a pair of judges with authority roughly equivalent to the Roman consul, known as sufetes (shophets), who were chosen from the most powerful noble families and served short terms.

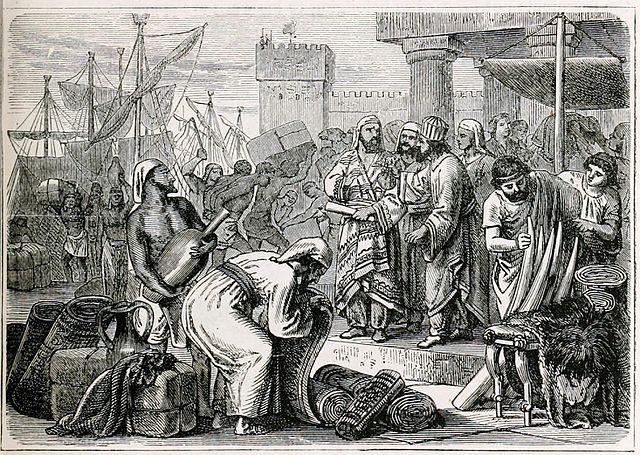

Nineteenth century depiction of Phoenician sailors and merchants.

The importance of trade to the Phoenician economy evidently led

to a gradual sharing of power between the king and assemblies of

merchant families.

Law

and administration :

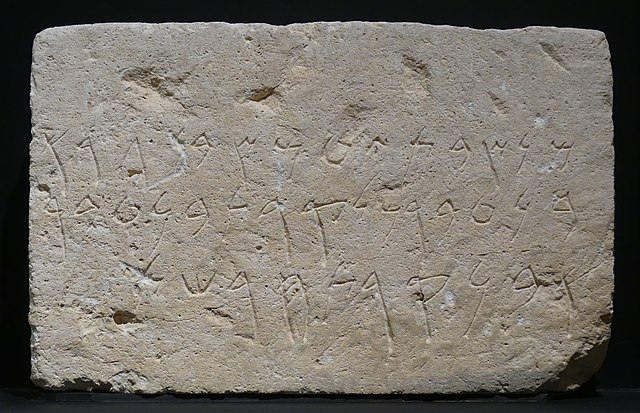

Stela from Tyre with Phoenician inscriptions (c. fourth century BC). National Museum of Beirut The Phoenicians had a system of courts and judges that resolved disputes and punished crimes based on a semi-codified body of laws and traditions. Laws were implemented by the state and were the responsibility of the ruler and certain designated officials. Like other Levantine societies, laws were harsh and biased, reflecting the social stratification of society. The murder of a commoner was treated as less serious than of a nobleman, and the upper classes had the most rights; the wealthy often escaped punishment by paying a fine. Free men of any class could represent themselves in court and had more rights than women and children, while slaves had no rights at all. Men could often deflect punishment to their wives, children, or slaves, even having them serve his sentence in his place. Lawyers eventually emerged as a profession for those who could not plead their own case. As in neighboring societies at the time, penalties for crimes were often severe, usually reflecting the principle of reciprocity; for example, the killing of a slave would be punished by having the offender's slave killed. Imprisonment was rare, with fines, exile, punishment, and execution the main remedies.

Military

:

Language

:

Alphabet :

Around 1050 BC, the Phoenicians developed a script for writing their own language. The Canaanite-Phoenician alphabet consists of 22 letters, all consonants (and is thus strictly an abjad). It is believed to be a continuation of the Proto-Sinaitic (or Proto-Canaanite) script attested in the Sinai and in Canaan in the Late Bronze Age. Through their maritime trade, the Phoenicians spread the use of the alphabet to Anatolia, North Africa, and Europe. The name Phoenician is by convention given to inscriptions beginning around 1050 BC, because Phoenician, Hebrew, and other Canaanite dialects were largely indistinguishable before that time. Phoenician inscriptions are found in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Cyprus and other locations, as late as the early centuries of the Christian era.

The alphabet was adopted and modified by the Greeks probably in the eighth century BC. This most likely did not occur in a single instance but in a process of commercial exchange. The legendary Phoenician hero Cadmus is credited with bringing the alphabet to Greece, but it is more plausible that it was brought by Phoenician immigrants to Crete, whence it gradually diffused northwards.

Art

:

Phoenician art also differed from its contemporaries in its continuance of Bronze Age conventions well into the Iron Age, such as terracotta masks. Phoenician artisans were known for their skill with wood, ivory, bronze, and textiles. In the Old Testament, a craftsman from Tyre is commissioned to build and decorate the legendary Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem, which "presupposes a well-developed and highly respected craft industry in Phoenicia by the mid-tenth century BC". The Iliad mentions the embroidered robes of Priam’s wife, Hecabe, as "the work of Sidonian women" and describes a mixing bowl of chased silver as "a masterpiece of Sidonian craftsmanship." [citation needed] The Assyrians appeared to have valued Phoenician ivory work in particular, collecting vast quantities in their palaces.

Phoenician art appears to have been indelibly tied to Phoenician commercial interests. They appear to have crafted goods to appeal to particular trading partners, distinguishing not only different cultures but even socioeconomic classes.

Decorative plaque which depicts a fighting of man and griffin; 900–800 BC; Nimrud ivories; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

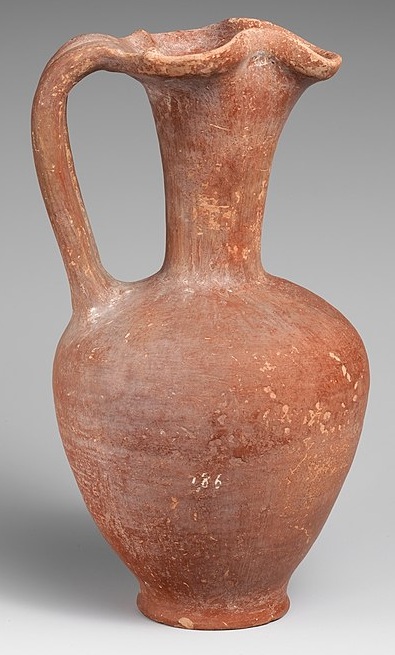

Oinochoe; 800–700 BC; terracotta; height: 24.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Face bead; mid-4th–3rd century BC; glass; height: 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Earring from a pair, each with four relief faces; late 4th–3rd century BC; gold; overall: 3.5 x 0.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Women :

Female figurines from Tyre (c.1000–550 BC). National Museum of Beirut Women in Phoenicia took part in public events and religious processions, with depictions of banquets showing them casually sitting or reclining with men, dancing, and playing music. In most contexts, however, women were expected to dress and behave more modestly than men; female figures are almost always portrayed as draped from head to feet, with the arms sometimes covered as well.

Although they rarely had political power, women took part in community affairs and had some voice in the popular assembles that began to emerge in some city states. At least one woman, Unmiashtart, is recorded to have ruled Sidon in the fifth century BC. The two most famous Phoenician women are political figures: Jezebel, portrayed in the Bible as the assertive princess of Sidon, and Dido, the semi-legendary founder and first queen of Carthage. In Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid, Dido is described as having been the co-ruler of Tyre, using cleverness to escape the tyranny of her brother Pygmalion and to secure an ideal site for Carthage.

Religion

:

Figure of Ba'al with raised arm, 14th – 12th century BC, found at ancient Ugarit (Ras Shamra site), a city at the far north of the Phoenician coast. Musée du Louvre Several Canaanite practices are attested in ancient sources and mentioned by scholars, such as temple prostitution and child sacrifice. Special sites known as "Tophets" were allegedly used by the Phoenicians "to burn their sons and their daughters in the fire", and are condemned by Yahweh in the Hebrew bible, particularly in Jeremiah 7:30–32, and in 2nd Kings 23:10 and 17:17. Notwithstanding these and other important differences, cultural and religious similarities between the ancient Hebrews and the Phoenicians persisted.

Canaanite religious mythology does not appear as elaborate as their Semitic cousins in Mesopotamia. In Canaan the supreme god was called El ("god"). The son of El was Baal ("master", "lord"), a powerful dying-and-rising storm god. Other gods were called by royal titles, such as Melqart, meaning "king of the city", or Adonis for "lord". Such epithets may often have been merely local titles for the same deities.

The Semitic pantheon was well-populated; which god became primary evidently depended on the exigencies of a particular city-state. Melqart was prominent throughout Phoenicia and overseas, as was Astarte, a fertility goddess with regal and matronly aspects.

Religious institutions in Tyre, called marzeh ("place of reunion"), did much to foster social bonding and "kin" loyalty. Marzeh held banquets for their membership on festival days, and many developed into elite fraternities. Each marzeh nurtured congeniality and community through a series of ritual meals, shared together among trusted kin in honor of deified ancestors. In Carthage, which had developed a complex republican system of government, the marzeh may have played a role in forging social and political ties among citizens; Carthaginians were divided into different institutions that were solidified through communal feasts and banquets. Such festival groups may also have composed the voting cohort for selecting members of the city-state's Assembly.

The Phoenicians made votive offerings to their gods, namely in the form of figurines and pottery vessels. Hundreds of figurines and fragments have been recovered from the Mediterranean, often spanning centuries between them, suggesting they were cast into the sea to ensure safe travels. Since the Phoenicians were a predominately seafaring people, it is speculated that many of their rituals were performed at sea or aboard ships, though the specific nature of these practices is unknown.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.svg.png)