| NINEVEH

Nineveh

The reconstructed Mashki Gate of Nineveh (since destroyed by ISIL)

Nineveh (Arabic: Naynawa; Romanized: Ninwe; Akkadian: URUNI.NU.A Ninua) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located on the outskirts of Mosul in modern-day northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River and was the capital and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as the largest city in the world for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country's Nineveh Governorate takes its name from it.

It was the largest city in the world for approximately fifty years until the year 612 BC when, after a bitter period of civil war in Assyria, it was sacked by a coalition of its former subject peoples including the Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. The city was never again a political or administrative centre, but by Late Antiquity it was the seat of a Christian bishop. It declined relative to Mosul during the Middle Ages and was mostly abandoned by the 13th century AD.

Its ruins lie across the river from the modern-day major city of Mosul, in Iraq's Nineveh Governorate. The two main tells, or mound-ruins, within the walls are Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell Nabi Yunus, site of a shrine to Jonah, the prophet who preached to Nineveh. Large amounts of Assyrian sculpture and other artifacts have been excavated there and are now located in museums around the world.

Name :

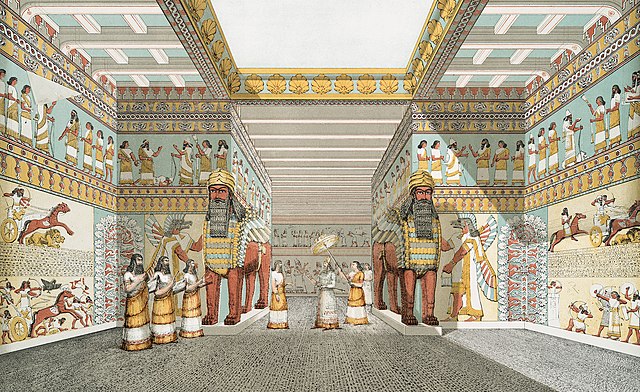

Artist's impression of Assyrian palaces from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853 The English placename Nineveh comes from Latin Ninive and Septuagint Greek Nineue under influence of the Biblical Hebrew Nineweh, from the Akkadian Ninua (var. Ninâ) or Old Babylonian Ninuwa. The original meaning of the name is unclear but may have referred to a patron goddess. The cuneiform for Ninâ is a fish within a house (cf. Aramaic nuna, "fish"). This may have simply intended "Place of Fish" or may have indicated a goddess associated with fish or the Tigris, possibly originally of Hurrian origin. The city was later said to be devoted to "the goddess Ishtar of Nineveh" and Nina was one of the Sumerian and Assyrian names of that goddess.

The city was also known as Ninuwa in Mari; Ninawa in Aramaic [clarification needed] and Nainava in Persian.

Nabi Yunus is the Arabic for "Prophet Jonah". Kuyunjiq was, according to Layard, a Turkish name, and it was known as Armousheeah by the Arabs, and is thought to have some connection with the Kara Koyunlu dynasty. These toponyms refer to the areas to the North and South of the Khosr stream, respectively: Kuyunjiq is the name for the whole northern sector enclosed by the city walls and is dominated by the large (35 ha) mound of Tell Kuyunjiq, while Nabi (or more commonly Nebi) Yunus is the southern sector around of the mosque of Prophet Yunus/Jonah, which is located on Tell Nebi Yunus.

Geography :

View of Nineveh in 2019 The remains of ancient Nineveh, the areas of Kuyunjiq and Nabi Yunus with their mounds, are located on a level part of the plain at the junction of the Tigris and the Khosr Rivers within an area of 750 hectares (1,900 acres) circumscribed by a 12-kilometre (7.5 mi) fortification wall. This whole extensive space is now one immense area of ruins overlaid by c. one third by the Nebi Yunus suburbs of the city of eastern Mosul.

The site of ancient Nineveh is bisected by the Khosr river. North of the Khosr, the site is called Kuyunjiq, including the acropolis of Tell Kuyunjiq; the illegal village of Rahmaniye lay in eastern Kuyunjiq. South of the Khosr, the urbanized area is called Nebi Yunus (also Ghazliya, Jezayr, Jammasa), including Tell Nebi Yunus where the mosque of the Prophet Jonah and a palace of Asarhaddon/Ashurbanipal below it are located. South of the street Al-'Asady (made by Daesh destroying swaths of the city walls) the area is called Jounub Ninawah or Shara Pepsi.

Nineveh was an important junction for commercial routes crossing the Tigris on the great roadway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, thus uniting the East and the West, it received wealth from many sources, so that it became one of the greatest of all the region's ancient cities, and the last capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

History

:

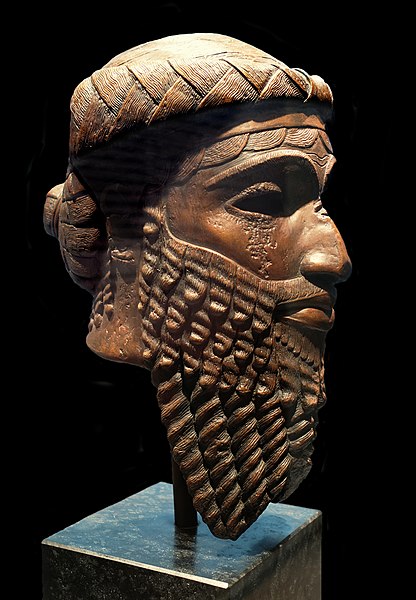

Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler, discovered in Nineveh in 1931, presumably depicting Sargon of Akkad's son Manishtushu, c. 2270 BC, Iraq Museum. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden Nineveh was one of the oldest and greatest cities in antiquity. The area it occupied was originally settled as early as 6000 BC during the late Neolithic period. Deep sounding at Nineveh uncovered soil layers that have been dated to early in the era of the Hassuna archaeological culture.

By 3000 BC, the area had become an important religious center for the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar. The early city (and subsequent buildings) was constructed on a fault line and, consequently, suffered damage from a number of earthquakes. One such event destroyed the first temple of Ishtar, which was rebuilt in 2260 BC by the Akkadian king Manishtushu.

Texts

from the Hellenistic period later offered an eponymous Ninus as

the founder of Nineveh, although there is no historical basis for

this.

Ninevite 5 was preceded by the Late Uruk period. Ninevite 5 pottery is roughly contemporary to the Early Transcaucasian culture ware, and the Jemdet Nasr period ware. Iraqi Scarlet Ware culture also belongs to this period; this colourful painted pottery is somewhat similar to Jemdet Nasr ware. Scarlet Ware was first documented in the Diyala River basin in Iraq. Later, it was also found in the nearby Hamrin Basin, and in Luristan.

Old

Assyrian period :

Mitanni period :

Artist's impression of a hall in an Assyrian palace from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853 The goddess's statue was sent to Pharaoh Amenhotep III of Egypt in the 14th century BC, by orders of the king of Mitanni. The Assyrian city of Nineveh became one of Mitanni's vassals for half a century until the early 14th century BC.

Middle

Assyrian period :

There is a large body of evidence to show that Assyrian monarchs built extensively in Nineveh during the late 3rd and 2nd millenniums BC; it appears to have been originally an "Assyrian provincial town". Later monarchs whose inscriptions have appeared on the high city include the Middle Assyrian Empire kings Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 BC), both of whom were active builders in Assur (Ashur).

Imperial

Nineveh :

Refined low-relief section of a bull-hunt frieze from Nineveh, alabaster, c. 695 BC (Pergamon Museum), Berlin

Relief of Ashurbanipal hunting a Mesopotamian lion, from the Northern Palace in Nineveh, as seen at the British Museum

Sennacherib's development of Nineveh :

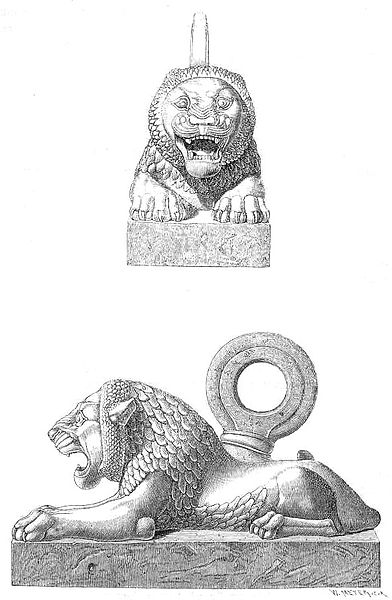

Some of the principal doorways were flanked by colossal stone lamassu door figures weighing up to 30,000 kilograms (30 t); these were winged Mesopotamian lions or bulls, with human heads. These were transported 50 kilometres (31 mi) from quarries at Balatai, and they had to be lifted up 20 metres (66 ft) once they arrived at the site, presumably by a ramp. There are also 3,000 metres (9,843 ft) of stone Assyrian palace reliefs, that include pictorial records documenting every construction step including carving the statues and transporting them on a barge. One picture shows 44 men towing a colossal statue. The carving shows three men directing the operation while standing on the Colossus. Once the statues arrived at their destination, the final carving was done. Most of the statues weigh between 9,000 and 27,000 kilograms (19,842 and 59,525 lb).

The stone carvings in the walls include many battle scenes, impalings and scenes showing Sennacherib's men parading the spoils of war before him. The inscriptions boasted of his conquests: he wrote of Babylon: "Its inhabitants, young and old, I did not spare, and with their corpses I filled the streets of the city." A full and characteristic set shows the campaign leading up to the siege of Lachish in 701; it is the "finest" from the reign of Sennacherib, and now in the British Museum. He later wrote about a battle in Lachish: "And Hezekiah of Judah who had not submitted to my yoke...him I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city like a caged bird. Earthworks I threw up against him, and anyone coming out of his city gate I made pay for his crime. His cities which I had plundered I had cut off from his land."

At this time, the total area of Nineveh comprised about 7 square kilometres (1,730 acres), and fifteen great gates penetrated its walls. An elaborate system of eighteen canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently constructed aqueduct erected by Sennacherib were discovered at Jerwan, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) distant. The enclosed area had more than 100,000 inhabitants (maybe closer to 150,000), about twice as many as Babylon at the time, placing it among the largest settlements worldwide.

Some scholars such as Stephanie Dalley at Oxford believe that the garden which Sennacherib built next to his palace, with its associated irrigation works, were the original Hanging Gardens of Babylon; Dalley's argument is based on a disputation of the traditional placement of the Hanging Gardens attributed to Berossus together with a combination of literary and archaeological evidence.

After Ashurbanipal :

The walls of Nineveh at the time of Ashurbanipal. 645 - 640 BC. British Museum BM 124938 The greatness of Nineveh was short-lived. In around 627 BC, after the death of its last great king Ashurbanipal, the Neo-Assyrian empire began to unravel through a series of bitter civil wars between rival claimants for the throne, and in 616 BC Assyria was attacked by its own former vassals, the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. In about 616 BC Kalhu was sacked, the allied forces eventually reached Nineveh, besieging and sacking the city in 612 BC, following bitter house-to-house fighting, after which it was razed. Most of the people in the city who could not escape to the last Assyrian strongholds in the north and west were either massacred or deported out of the city and into the countryside where they founded new settlements. Many unburied skeletons were found by the archaeologists at the site. The Assyrian empire then came to an end by 605 BC, the Medes and Babylonians dividing its colonies between themselves.

It is not clear whether Nineveh came under the rule of the Medes or the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 612. The Babylonian Chronicle Concerning the Fall of Nineveh records that Nineveh was "turned into mounds and heaps", but this is literary hyperbole. The complete destruction of Nineveh has traditionally been seen as confirmed by the Hebrew Book of Ezekiel and the Greek Retreat of the Ten Thousand of Xenophon (d. 354 BC). To the Greek historians Ctesias and Herodotus (c. 400 BC), Nineveh was a thing of the past; and when Xenophon passed the place in the 4th century BC he described it as abandoned. There are no later cuneiform tablets in Akkadian from Nineveh. Although devastated in 612, the city was never completely abandoned.

Later

history :

Archaeologically, there is evidence of repairs at the temple of Nabu after 612 and for the continued use of Sennacherib's palace. There is evidence of syncretic Hellenistic cults. A statue of Hermes has been found and a Greek inscription attached to a shrine of the Sebitti. A statue of Herakles Epitrapezios dated to the 2nd century AD has also been found. The library of Ashurbanipal may still have been in use until around the time of Alexander the Great.

The city was actively resettled under the Seleucid Empire. There is evidence of more changes in Sennacherib's palace under the Parthian Empire. The Parthians also established a municipal mint at Nineveh coining in bronze. According to Tacitus, in AD 50 Meherdates, a claimant to the Parthian throne with Roman support, took Nineveh.

By Late Antiquity, Nineveh was restricted to the east bank of the Tigris and the west bank was uninhabited. Under the Sasanian Empire, Nineveh was not an administrative centre. By the 2nd century AD there were Christians present and by 554 it was a bishopric of the Church of the East. King Khosrow II (591–628) built a fortress on the west bank, and two Christian monasteries were constructed around 570 and 595. This growing settlement was not called Mosul until after the Arab conquests. It may have been called Hesna Ebraye (Jews' Fort).

In 627, the city was the site of the Battle of Nineveh between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanians. In 641, it was conquered by the Arabs, who built a mosque on the west bank and turned it into an administrative centre. Under the Umayyad dynasty, it eclipsed Nineveh, which was reduced to a Christian suburb with limited new construction. By the 13th century, Nineveh was mostly ruins. A church was converted into a Muslim shrine to the prophet Jonah, which continued to attract pilgrims until its destruction by ISIL in 2014.

Biblical

Nineveh :

The Prophet Jonah before the Walls of Nineveh, drawing by Rembrandt, c. 1655 Nineveh was the flourishing capital of the Assyrian Empire and was the home of King Sennacherib, King of Assyria, during the Biblical reign of King Hezekiah and the lifetime of Judean prophet Isaiah. As recorded in Hebrew scripture, Nineveh was also the place where Sennacherib died at the hands of his two sons, who then fled to the vassal land of `rrt Urartu. The book of the prophet Nahum is almost exclusively taken up with prophetic denunciations against Nineveh. Its ruin and utter desolation are foretold. Its end was strange, sudden, and tragic. According to the Bible, it was God's doing, His judgment on Assyria's pride (Isaiah 10:5–19). In fulfillment of prophecy, God made "an utter end of the place". It became a "desolation". The prophet Zephaniah also predicts its destruction along with the fall of the empire of which it was the capital. Nineveh is also the setting of the Book of Tobit.

The Book of Jonah, set in the days of the Assyrian empire, describes it as an "exceedingly great city of three days' journey in breadth", whose population at that time is given as "more than 120,000". Genesis 10:11-12 lists four cities "Nineveh, Rehoboth, Calah, and Resen", ambiguously stating that either Resen or Calah is "the great city." The ruins of Kuyunjiq, Nimrud, Karamles and Khorsabad form the four corners of an irregular quadrangle. The ruins of the "great city" Nineveh, with the whole area included within the parallelogram they form by lines drawn from the one to the other, are generally regarded as consisting of these four sites. The description of Nineveh in Jonah likely was a reference to greater Nineveh, including the surrounding cities of Rehoboth, Calah and Resen The Book of Jonah depicts Nineveh as a wicked city worthy of destruction. God sent Jonah to preach to the Ninevites of their coming destruction, and they fasted and repented because of this. As a result, God spared the city; when Jonah protests against this, God states He is showing mercy for the population who are ignorant of the difference between right and wrong ("who cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand") and mercy for the animals in the city.

Nineveh's repentance and salvation from evil can be found in the Hebrew Tanakh, aka the Old Testament, and referred to in the Christian Bible and Muslim Quran. To this day, Syriac and Oriental Orthodox churches commemorate the three days Jonah spent inside the fish during the Fast of Nineveh. The Christians observing this holiday fast by refraining from food and drink. Churches encourage followers to refrain from meat, fish and dairy products.

Archaeology

:

Carsten Niebuhr recorded its location during the 1761–67 Danish expedition. Niebuhr wrote afterwards that "I did not learn that I was at so remarkable a spot, till near the river. Then they showed me a village on a great hill, which they call Nunia, and a mosque, in which the prophet Jonah was buried. Another hill in this district is called Kalla Nunia, or the Castle of Nineveh. On that lies a village Koindsjug."

Excavation

history :

Bronze lion from Nineveh In 1847 the young British diplomat Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins. Layard did not use modern archaeological methods; his stated goal was "to obtain the largest possible number of well preserved objects of art at the least possible outlay of time and money." In the Kuyunjiq mound, Layard rediscovered in 1849 the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and colossal bas-reliefs. He also unearthed the palace and famous library of Ashurbanipal with 22,000 cuneiform clay tablets. Most of Layard's material was sent to the British Museum, but others were dispersed elsewhere as two large pieces which were given to Lady Charlotte Guest and eventually found their way to the Metropolitan Museum. The study of the archaeology of Nineveh reveals the wealth and glory of ancient Assyria under kings such as Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) and Ashurbanipal (669–626 BC).

The work of exploration was carried on by Hormuzd Rassam (a modern Assyrian), George Smith and others, and a vast treasury of specimens of Assyria was incrementally exhumed for European museums. Palace after palace was discovered, with their decorations and their sculptured slabs, revealing the life and manners of this ancient people, their arts of war and peace, the forms of their religion, the style of their architecture, and the magnificence of their monarchs.

The mound of Kuyunjiq was excavated again by the archaeologists of the British Museum, led by Leonard William King, at the beginning of the 20th century. Their efforts concentrated on the site of the Temple of Nabu, the god of writing, where another cuneiform library was supposed to exist. However, no such library was ever found: most likely, it had been destroyed by the activities of later residents.

The excavations started again in 1927, under the direction of Campbell Thompson, who had taken part in King's expeditions. Some works were carried out outside Kuyunjiq, for instance on the mound of Tell Nebi Yunus, which was the ancient arsenal of Nineveh, or along the outside walls. Here, near the northwestern corner of the walls, beyond the pavement of a later building, the archaeologists found almost 300 fragments of prisms recording the royal annals of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal, beside a prism of Esarhaddon which was almost perfect.

After the Second World War, several excavations were carried out by Iraqi archaeologists. From 1951 to 1958 Mohammed Ali Mustafa worked the site. The work was continued from 1967 through 1971 by Tariq Madhloom. Some additional excavation occurred by Manhal Jabur from the early 1970s to 1987. For the most part, these digs focused on Tell Nebi Yunus.

The British archaeologist and Assyriologist Professor David Stronach of the University of California, Berkeley conducted a series of surveys and digs at the site from 1987 to 1990, focusing his attentions on the several gates and the existent mudbrick walls, as well as the system that supplied water to the city in times of siege. The excavation reports are in progress.

Most recently, an Iraqi-Italian Archaeological Expedition by the Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna and the Iraqi SBAH, led by prof. Nicolò Marchetti, begun in September-November 2019 (with a second campaign having taken place in the Fall of 2020) a long-term project aiming at the excavation, conservation and public presentation of Eastern Nineveh (NINEV_E project). Work was carried out in nine excavation areas, from the Adad Gate - now completely repaired after removing hundreds of tons of debris from ISIL's destructions, explored and protected with a new roof - deep into the Nebi Yunus town. In three areas a very thick later stratigraphy was encountered, but the late 7th century BC stratum was reached everywhere (actually in one area in the pre-Sennacherib lower town the excavations already exposed an 11th-century BC stratum, aiming in the future at exploring the first settlement therein). The site is greatly endangered with dumping of debris, illegal settlements and quarrying as the main threats.

Archaeological remains :

Humvee down after ISIS attack Today, Nineveh's location is marked by two large mounds, Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell Nabi Yunus "Prophet Jonah", and the remains of the city walls (about 12 kilometres (7 mi) in circumference). The Neo-Assyrian levels of Kuyunjiq have been extensively explored. The other mound, Nabi Yunus, has not been as extensively explored because there was an Arab Muslim shrine dedicated to that prophet on the site. On July 24, 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant destroyed the shrine as part of a campaign to destroy religious sanctuaries it deemed "un-Islamic."

The ruin mound of Kuyunjiq rises about 20 metres (66 ft) above the surrounding plain of the ancient city. It is quite broad, measuring about 800 by 500 metres (2,625 ft × 1,640 ft). Its upper layers have been extensively excavated, and several Neo-Assyrian palaces and temples have been found there. A deep sounding by Max Mallowan revealed evidence of habitation as early as the 6th millennium BC. Today, there is little evidence of these old excavations other than weathered pits and earth piles. In 1990, the only Assyrian remains visible were those of the entry court and the first few chambers of the Palace of Sennacherib. Since that time, the palace chambers have received significant damage by looters. Portions of relief sculptures that were in the palace chambers in 1990 were seen on the antiquities market by 1996. Photographs of the chambers made in 2003 show that many of the fine relief sculptures there have been reduced to piles of rubble.

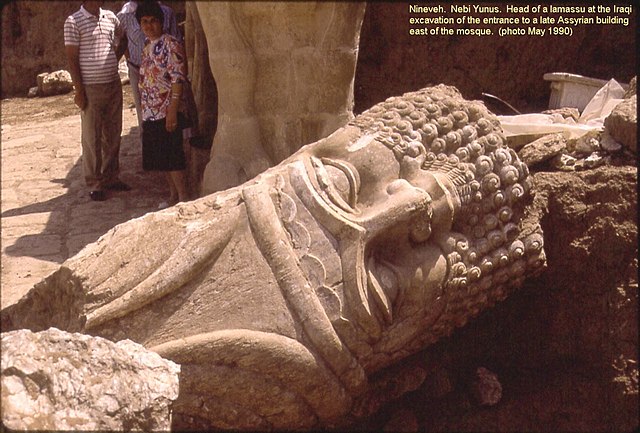

Winged Bull excavated at Tell Nebi Yunus by Iraqi archaeologists Tell Nebi Yunus is located about 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) south of Kuyunjiq and is the secondary ruin mound at Nineveh. On the basis of texts of Sennacherib, the site has traditionally been identified as the "armory" of Nineveh, and a gate and pavements excavated by Iraqis in 1954 have been considered to be part of the "armory" complex. Excavations in 1990 revealed a monumental entryway consisting of a number of large inscribed orthostats and "bull-man" sculptures, some apparently unfinished.

Following the Mosul liberation, the tunnels under Tell Nebi Yunus were explored in 2018, in which a 3000-year-old palace was discovered, including a pair of reliefs, each showing a row of women, along with reliefs of lamassu.

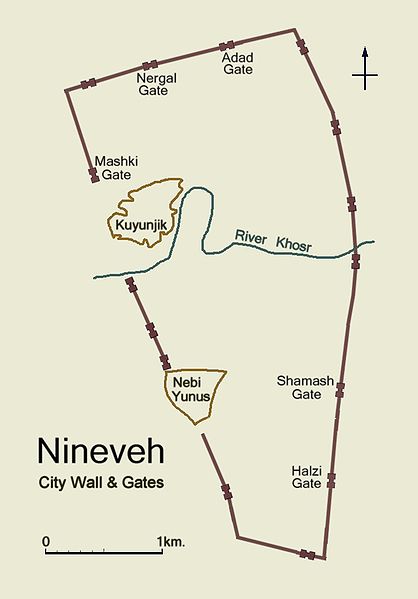

City wall and gates :

Simplified plan of ancient Nineveh showing city wall and location of gateways The ruins of Nineveh are surrounded by the remains of a massive stone and mudbrick wall dating from about 700 BC. About 12 km in length, the wall system consisted of an ashlar stone retaining wall about 6 metres (20 ft) high surmounted by a mudbrick wall about 10 metres (33 ft) high and 15 metres (49 ft) thick. The stone retaining wall had projecting stone towers spaced about every 18 metres (59 ft). The stone wall and towers were topped by three-step merlons.

Five of the gateways have been explored to some extent by archaeologists :

•

Mashki

Gate :

•

Nergal Gate :

• Adad Gate :

Photograph of the restored Adad Gate, taken prior to the gate's destruction by ISIL in April 2016 Adad Gate was named for the god Adad. A reconstruction was begun in the 1960s by Iraqis but was not completed. The result was a mixture of concrete and eroding mudbrick, which nonetheless does give some idea of the original structure. The excavator left some features unexcavated, allowing a view of the original Assyrian construction. The original brickwork of the outer vaulted passageway was well exposed, as was the entrance of the vaulted stairway to the upper levels. The actions of Nineveh's last defenders could be seen in the hastily built mudbrick construction which narrowed the passageway from 4 to 2 metres (13 to 7 ft). Around April 13, 2016, ISIL demolished both the gate and the adjacent wall by flattening them with a bulldozer.

• Shamash Gate :

Eastern city wall and Shamash Gate Named for the Sun god Shamash, it opens to the road to Erbil. It was excavated by Layard in the 19th century. The stone retaining wall and part of the mudbrick structure were reconstructed in the 1960s. The mudbrick reconstruction has deteriorated significantly. The stone wall projects outward about 20 metres (66 ft) from the line of main wall for a width of about 70 metres (230 ft). It is the only gate with such a significant projection. The mound of its remains towers above the surrounding terrain. Its size and design suggest it was the most important gate in Neo-Assyrian times.

•

Hali

Gate :

Threats

to the site :

The ailing Mosul Dam is a persistent threat to Nineveh as well as the city of Mosul. This is in no small part due to years of disrepair (in 2006, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cited it as the most dangerous dam in the world), the cancellation of a second dam project in the 1980s to act as flood relief in case of failure, and occupation by ISIL in 2014 resulting in fleeing workers and stolen equipment. If the dam fails, the entire site could be under as much as 45 feet (14 m) of water.

In an October 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund named Nineveh one of 12 sites most "on the verge" of irreparable destruction and loss, citing insufficient management, development pressures and looting as primary causes.

By far, the greatest threat to Nineveh has been purposeful human actions by ISIL, which first occupied the area in the mid-2010s. In early 2015, they announced their intention to destroy the walls of Nineveh if the Iraqis tried to liberate the city. They also threatened to destroy artifacts. [citation needed] On February 26 they destroyed several items and statues in the Mosul Museum and are believed to have plundered others to sell overseas. The items were mostly from the Assyrian exhibit, which ISIL declared blasphemous and idolatrous. There were 300 items in the museum out of a total of 1,900, with the other 1,600 being taken to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad for security reasons prior to the 2014 Fall of Mosul. [according to whom?] Some of the artifacts sold and/or destroyed were from Nineveh. Just a few days after the destruction of the museum pieces, they demolished remains at major UNESCO world heritage sites Khorsabad, Nimrud, and Hatra.

Rogation

of the Ninevites (Nineveh's Wish) :

Popular

culture :

John Martin, The Fall of Nineveh Atherstone's friend, the artist John Martin, created a painting of the same name inspired by the poem. The English poet John Masefield's well-known, fanciful 1903 poem Cargoes mentions Nineveh in its first line. Nineveh is also mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's 1897 poem Recessional and in Arthur O'Shaughnessy's 1873 poem Ode.

The 1962 Italian peplum movie, War Gods of Babylon, is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In the 1973 film The Exorcist Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig near Nineveh prior to returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Reagan MacNiel.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

|||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)