| NIPPUR

Nippur

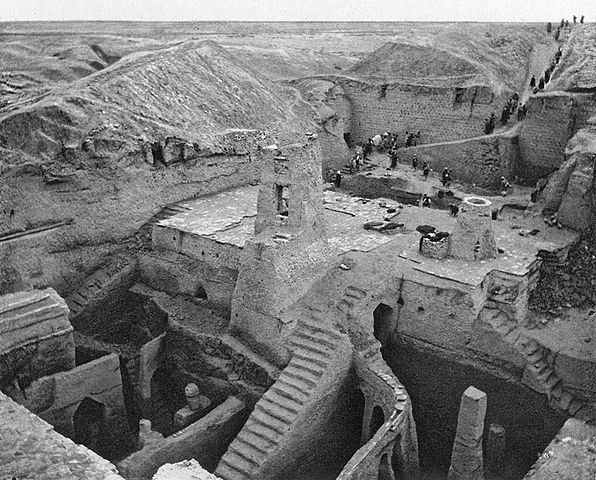

Ruins of a temple platform in Nippur - the brick structure on top was constructed by American archaeologists around 1900

Nippur (Sumerian: Nibru, often logographically recorded as EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;" Akkadian: Nibbur) was an ancient Sumerian city. It was the special seat of the worship of the Sumerian god Enlil, the "Lord Wind", ruler of the cosmos, subject to An alone. Nippur was located in modern Nuffar in Afak, Al-Qadisiyyah Governorate, Iraq.

History

:

According to the Tummal Chronicle, Enmebaragesi, an early ruler of Kish, was the first to build up this temple.His influence over Nippur has also been detected archaeologically. The Chronicle lists successive early Sumerian rulers who kept up intermittent ceremonies at the temple: Aga of Kish, son of Enmebaragesi; Mesannepada of Ur; his son Meskiang-nunna; Gilgamesh of Uruk; his son Ur-Nungal; Nanni of Ur and his son Meskiang-nanna. It also indicates that the practice was revived in Neo-Sumerian times by Ur-Nammu of Ur, and continued until Ibbi-Sin appointed Enmegalana high priest in Uruk (c. 1950 BCE).

Inscriptions of Lugal-Zage-Si and Lugal-kigub-nidudu, kings of Uruk and Ur respectively, and of other early rulers, on door-sockets and stone vases, show the veneration in which the ancient shrine was then held, and the importance attached to its possession, as giving a certain stamp of legitimacy. On their votive offerings, some of these rulers designate themselves as ensis, or governors.

Pre-Sargonic era :

Indus Civilisation carnelian bead with white design, ca. 2900 – 2350 BCE. Found in Nippur. An example of early Indus-Mesopotamia relations Originally a village of reed huts in the marshes, Nippur was especially prone to devastation by flooding or fire. For some reason, settlement persisted at the same spot, and gradually the site rose above the marshes – partly from the accumulation of debris, and partly through the efforts of the inhabitants. As the inhabitants began to develop in civilization, they substituted, at least in the case of their shrine, mud-brick buildings instead of reed huts. The earliest age of civilization, the "clay age", is marked by crude, hand-made pottery and thumb-marked bricks – flat on one side, concave on the other, gradually developing through several fairly marked stages. The exact form of the sanctuary at that period cannot be determined, but it seems to have been connected with the burning of the dead, and extensive remains of such cremation are found in all the earlier, pre-Sargonic strata. There is evidence of the succession on the site of different peoples, varying somewhat in their degrees of civilization. One stratum is marked by painted pottery of good make, similar to that found in a corresponding stratum in Susa, and resembling early Aegean pottery more closely than any later pottery found in Sumer.

This people gave way in time to another, markedly inferior in the manufacture of pottery, but apparently superior as builders. In one of these earlier strata, of very great antiquity, there was discovered, in connection with the shrine, a conduit built of bricks in the form of an arch. At some point, Sumerian inscriptions began to be written on clay, in an almost linear script. The shrine at this time stood on a raised platform, and apparently contained a ziggurat.

Akkadian, Ur III, and Old Babylonian periods :

Incised devotional plaque, Nippur

The vase of Lugalzagesi, found in Nippur Late in the 3rd millennium BCE, Nippur was conquered and occupied by the Semitic rulers of Akkad, or Agade, and numerous votive objects of Sargon, Rimush, and Naram-Sin testify to the veneration in which they also held this sanctuary. Naram-Sin rebuilt both the Ekur temple and the city walls, and in the accumulation of debris now marking the ancient site, his remains are found about halfway from the top to the bottom. One of the few instances of Nippur being recorded as having its own ruler comes from a tablet depicting a revolt of several Mesopotamian cities against Naram-Sin, including Nippur under Amar-enlila. The tablet goes on to relate that Naram-Sin defeated these rebel cities in nine battles, and brought them back under his control. The Weidner tablet (ABC 19) suggests that the Akkadian Empire fell as divine retribution, because of Sargon's initiating the transfer of "holy city" status from Nippur to Babylon.

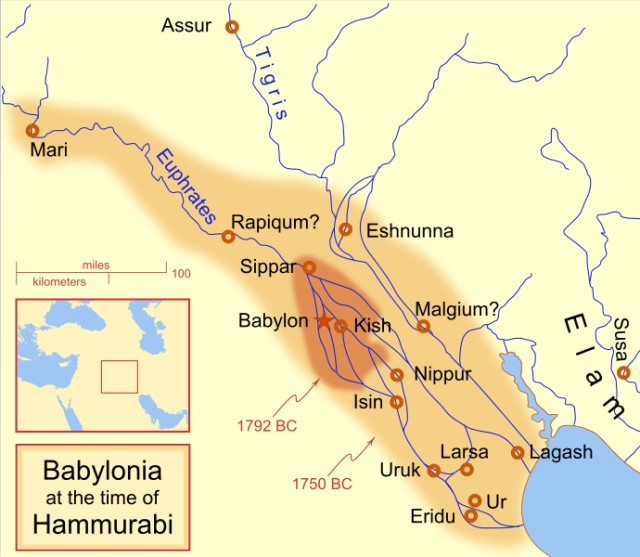

Babylonia in the time of Hammurabi This Akkadian occupation was succeeded by occupation during the third dynasty of Ur, and the constructions of Ur-Nammu, the great builder of temples, are superimposed immediately upon those of Naram-Sin. Ur-Nammu gave the temple its final characteristic form. Partly razing the constructions of his predecessors, he erected a terrace of bricks, some 12 m high, covering a space of about 32,000 m2. Near the northwestern edge, towards the western corner, he built a ziggurat of three stages of dry brick, faced with kiln-fired bricks laid in bitumen. On the summit stood, as at Ur and Eridu, a small chamber, the special shrine or abode of the god. Access to the stages of the ziggurat, from the court beneath, was by an inclined plane on the south-east side. To the north-east of the ziggurat stood, apparently, the House of Bel, and in the courts below the ziggurat stood various other buildings, shrines, treasure chambers, and the like. The whole structure was oriented with the corners toward the cardinal points of the compass.

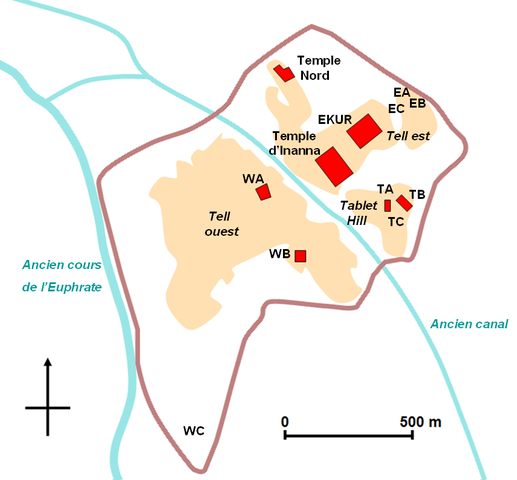

Ur-Nammu also rebuilt the walls of the city on the line of Naram-Sin's walls. The restoration of the general features of the temple of this, and the immediately succeeding periods, has been greatly facilitated by the discovery of a sketch map on a fragment of a clay tablet. This sketch map represents a quarter of the city to the east of the Shatt-en-Nil canal. This quarter was enclosed within its own walls, a city within a city, forming an irregular square, with sides roughly 820 m long, separated from the other quarters, and from the country to the north and east, by canals on all sides, with broad quays along the walls. A smaller canal divided this quarter of the city itself into two parts. In the south-eastern part, in the middle of its southeast side, stood the temple, while in the northwest part, along the Shatt-en-Nil, two great storehouses are indicated. The temple proper, according to this plan, consisted of an outer and inner court, each covering approximately 8 acres (32,000 m2), surrounded by double walls, with a ziggurat on the north-western edge of the latter.

The temple continued to be built upon or rebuilt by kings of various succeeding dynasties, as shown by bricks and votive objects bearing the inscriptions of the kings of various dynasties of Ur and Isin. It seems to have suffered severely in some manner at or about the time the Elamites invaded, as shown by broken fragments of statuary, votive vases, and the like, from that period. At the same time it seems to have won recognition from the Elamite conquerors, so that Rim-Sin I, the Elamite king of Larsa, styles himself "shepherd of the land of Nippur". With the establishment of the Babylonian empire, under Hammurabi, early in the 2nd millennium BCE, the religious, as well as the political center of influence, was transferred to Babylon, Marduk became lord of the pantheon, many of Enlil's attributes were transferred to him, and Ekur, Enlil's temple, was to some extent neglected.

Kassite

through Sassanid periods :

Islamic

period and eventual abandonment :

Archaeology :

Map of the site in French

Nippur, Temple of Bel excavation, 1896

Nippur excavations, 1893

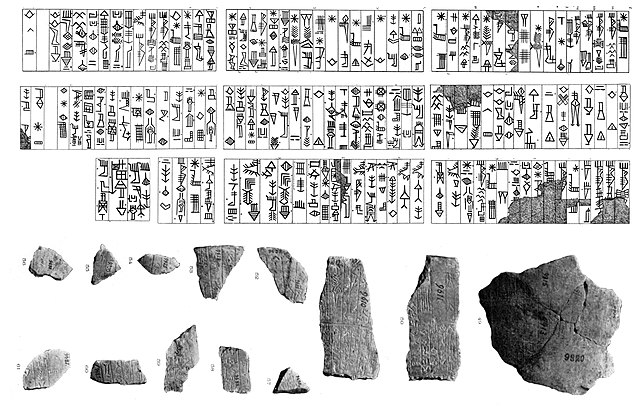

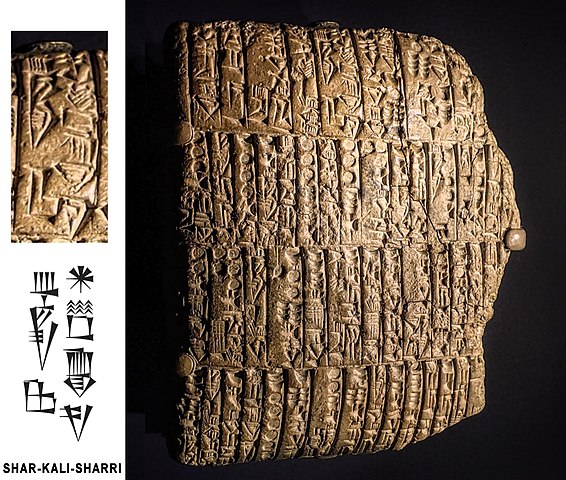

Cuneiform tablet from Nippur, in the name of Shar-Kali-Sharri, 2300 - 2100 BCE

Babylonian cuneiform tablet with a map from Nippur, Kassite period, 1550 - 1450 BCE Nippur was situated on both sides of the Shatt-en-Nil canal, one of the earliest courses of the Euphrates, between the present bed of that river and the Tigris, almost 160 km southeast of Baghdad. It is represented by the great complex of ruin mounds known to the Arabs as Nuffar, written by the earlier explorers Niffer, divided into two main parts by the dry bed of the old Shatt-en-Nil (Arakhat). The highest point of these ruins, a conical hill rising about 30 m above the level of the surrounding plain, northeast of the canal bed, is called by the Arabs Bint el-Amiror "prince's daughter".

Nippur was first excavated, briefly, by Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1851. Full-scale digging was begun by an expedition from the University of Pennsylvania. The work involved four seasons of excavation between 1889 and 1900 and was led by John Punnett Peters, John Henry Haynes, and Hermann Volrath Hilprecht.

Nippur was excavated for 19 seasons between 1948 and 1990 by a team from the Oriental Institute of Chicago, joined at times by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the American Schools of Oriental Research.

The Oriental Institute resumed work at Nippur in April 2019 under Abbas Alizadeh.

As at Tello, so at Nippur, the clay archives of the temple were found not in the temple proper, but on an outlying mound. South-eastward of the temple quarter, without the walls above, described, and separated from it by a large basin connected with the Shatt-en-Nil, lay a triangular mound, about 7.5 m in average height and 52.000 m2 in extent. In this were found large numbers of inscribed clay tablets (it is estimated that upward of 40,000 tablets and fragments have been excavated in this mound alone), dating from the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE onward into the Persian period, partly temple archives, partly school exercises and text-books, partly mathematical tables, with a considerable number of documents of a more distinctly literary character.[citation needed]

Almost directly opposite the temple, a large palace was excavated, apparently of the Seleucid period, and in this neighborhood and further southward on these mounds large numbers of inscribed tablets of various periods, including temple archives of the Kassite and commercial archives of the Persian period, were excavated. The latter, the "books and papers" of the house of Murashu, commercial agents of the government, throw light on the condition of the city and the administration of the country in the Persian period, the 5th century BCE. The former gives us a very good idea of the administration of an ancient temple. The whole city of Nippur appears to have been at that time merely an appendage of the temple. The temple itself was a great landowner, possessed of both farms and pasture land. Its tenants were obliged to render careful accounts of their administration of the property entrusted to their care, which was preserved in the archives of the temple. We have also from these archives lists of goods contained in the temple treasuries and salary lists of temple officials, on tablet forms specially prepared and marked off for periods of a year or less.[citation needed]

The Persian conquest of Mesopotamia in 539 BCE resulted in improved irrigation, and thus immigration increased, drawing Lydians, Phrygians, Carians, Cilicians, Egyptians, Jews (many of whom were deported to Babylonia), Persians, Medes, Sacae, etc. to the area. In Nippur, the house of Murashu's surviving documents are reflective of this diverse populace as one-third of contracts depict non-Babylonian names, and they evidently intermingled peaceably. Enduring for at least three successive generations, the house of Murashu capitalized on the enterprise of renting substantial plots of farmland having been awarded to occupying Persian governors, nobility, soldiery, probably at discounted rates, whose owners were most likely satisfied with a moderate return. The business would then subdivide these into smaller plots for cultivation by indigenous farmers and recent foreign settlers for a lucrative fee. The house of Murashu leased land, subdivided it, then subleased or rented out the smaller parcels, thereby simply acting as an intermediary. It thereby profited both from the collected rents and percentage of amassed credit reflective of that year's future crop harvests after supplying needed farming implements, means of irrigation, and paying taxes. In 423/422 BCE, the house of Murashu took in "about 20,000 kg or 20,000 shekels of silver". "The activities of the house of Murashu had a ruinous effect upon the economy of the country and thus led to the bankruptcy of the landowners. Although the house of Murashu loaned money to the landowners initially, after a few decades it began more and more to take the landowners' place, and the land began to concentrate in its hands."

On the upper surface of these mounds was found a considerable Jewish town, dating from about the beginning of the Arabic period onward to the 10th century AD, in the houses of which were large numbers of incantation bowls. Jewish names, appearing in the Persian documents discovered at Nippur, show, however, that Jewish settlement at that city dates in fact from a much earlier period.

Drehem

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

|||||||||||

.jpg)