| SUMER

Sumer (c. 4500 – 1900 BC)

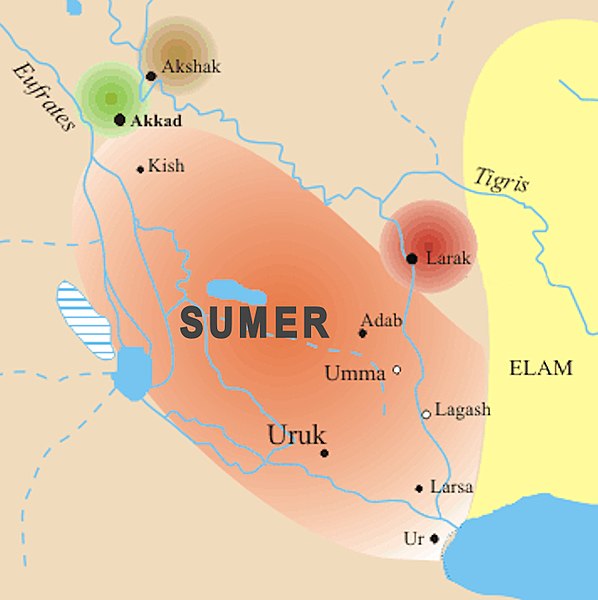

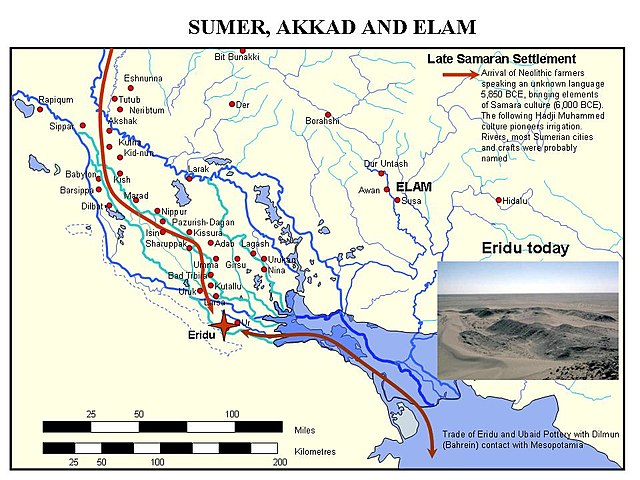

General location on a modern map, and main cities of Sumer with ancient coastline. The coastline was nearly reaching Ur in ancient times Geographical

range : Mesopotamia, Near East, Middle East

Sumer is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now southern Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is also one of the first civilizations in the world, along with Ancient Egypt, Norte Chico, the Minoan civilization, Ancient China, and the Indus Valley Civilization. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, the surplus from which enabled them to form urban settlements. Proto-writing dates back before 3000 BC. The earliest texts come from the cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between c. 3500 and c. 3000 BC.

Name :

Left: Sculpture of the head of Sumerian ruler Gudea, c. 2150 BC.

Right: cuneiform characters for Sag-gíg, "Black Headed

Ones", the native designation for the Sumerians. The first

is the pictographic character for "head" (

The Akkadian word Šumer may represent the geographical name in dialect, but the phonological development leading to the Akkadian term šumerû is uncertain. Hebrew Šinar, Egyptian Sngr, and Hittite Šanhar(a), all referring to southern Mesopotamia, could be western variants of Sumer.

Origins

:

The Blau Monuments combine proto-cuneiform characters and illustrations of early Sumerians, Jemdet Nasr period, 3100 – 2700 BC. British Museum However, with evidence strongly suggesting the first farmers originated from the fertile crescent, this suggestion is often discarded. Alternatively, a recent (2013) genetic analysis of four ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA samples suggests an association of the Sumerians with Indus Valley Civilization, possibly as a result of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations. According to some data, the Sumerians are associated with the Hurrians and Urartians, and the Caucasus is considered their homeland.

These prehistoric people before the Sumerians are now called "proto-Euphrateans" or "Ubaidians", and are theorized to have evolved from the Samarra culture of northern Mesopotamia. The Ubaidians, though never mentioned by the Sumerians themselves, are assumed by modern-day scholars to have been the first civilizing force in Sumer. They drained the marshes for agriculture, developed trade, and established industries, including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery.

Enthroned Sumerian king of Ur, possibly Ur-Pabilsag, with attendants. Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BC Juris Zarins believes the Sumerians lived along the coast of Eastern Arabia, today's Persian Gulf region, before it was flooded at the end of the Ice Age.

Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods. During the 3rd millennium BC, a close cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians, who spoke a language isolate, and Akkadians, which gave rise to widespread bilingualism. The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian (and vice versa) is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the 3rd millennium BC as a Sprachbund.

The Sumerians progressively lost control to Semitic states from the northwest. Sumer was conquered by the Semitic-speaking kings of the Akkadian Empire around 2270 BC (short chronology), but Sumerian continued as a sacred language. Native Sumerian rule re-emerged for about a century in the Third Dynasty of Ur at approximately 2100–2000 BC, but the Akkadian language also remained in use for some time.

The Sumerian city of Eridu, on the coast of the Persian Gulf, is considered to have been one of the oldest cities, where three separate cultures may have fused: that of peasant Ubaidian farmers, living in mud-brick huts and practicing irrigation; that of mobile nomadic Semitic pastoralists living in black tents and following herds of sheep and goats; and that of fisher folk, living in reed huts in the marshlands, who may have been the ancestors of the Sumerians.

City-states

in Mesopotamia :

Principal cities :

1.

Eridu (Tell Abu Shahrain)

1.

Kuara (Tell al-Lahm)

Apart from Mari, which lies full 330 kilometres (205 miles) north-west of Agade, but which is credited in the king list as having "exercised kingship" in the Early Dynastic II period, and Nagar, an outpost, these cities are all in the Euphrates-Tigris alluvial plain, south of Baghdad in what are now the Babil, Diyala, Wasit, Dhi Qar, Basra, Al-Muthanna and Al-Qadisiyyah governorates of Iraq.

History :

Portrait of a Sumerian prisoner on a victory stele of Sargon of

Akkad, c. 2300 BC. The hairstyle of the prisoners (curly hair on

top and short hair on the sides) is characteristic of Sumerians,

as also seen on the Standard of Ur. Louvre Museum.

Ubaid period :

The Ubaid period is marked by a distinctive style of fine quality painted pottery which spread throughout Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. During this time, the first settlement in southern Mesopotamia was established at Eridu (Cuneiform: nun.ki), c. 6500 BC, by farmers who brought with them the Hadji Muhammed culture, which first pioneered irrigation agriculture. It appears that this culture was derived from the Samarran culture from northern Mesopotamia. It is not known whether or not these were the actual Sumerians who are identified with the later Uruk culture. The story of the passing of the gifts of civilization (me) to Inanna, goddess of Uruk and of love and war, by Enki, god of wisdom and chief god of Eridu, may reflect the transition from Eridu to Uruk.

Uruk

period :

Uruk King-priest feeding the sacred herd

The king-priest and his acolyte feeding the sacred herd. Uruk period, c. 3200 BC

Cylinder-seal of the Uruk period and its impression, c. 3100 BC. Louvre Museum By the time of the Uruk period (c. 4100–2900 BC calibrated), the volume of trade goods transported along the canals and rivers of southern Mesopotamia facilitated the rise of many large, stratified, temple-centered cities (with populations of over 10,000 people) where centralized administrations employed specialized workers. It is fairly certain that it was during the Uruk period that Sumerian cities began to make use of slave labor captured from the hill country, and there is ample evidence for captured slaves as workers in the earliest texts. Artifacts, and even colonies of this Uruk civilization have been found over a wide area—from the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and as far east as central Iran.[page needed]

The Uruk period civilization, exported by Sumerian traders and colonists (like that found at Tell Brak), had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures. The cities of Sumer could not maintain remote, long-distance colonies by military force.

Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic and were most likely headed by a priest-king (ensi), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women. It is quite possible that the later Sumerian pantheon was modeled upon this political structure. There was little evidence of organized warfare or professional soldiers during the Uruk period, and towns were generally unwalled. During this period Uruk became the most urbanized city in the world, surpassing for the first time 50,000 inhabitants.

The ancient Sumerian king list includes the early dynasties of several prominent cities from this period. The first set of names on the list is of kings said to have reigned before a major flood occurred. These early names may be fictional, and include some legendary and mythological figures, such as Alulim and Dumizid.

The end of the Uruk period coincided with the Piora oscillation, a dry period from c. 3200–2900 BC that marked the end of a long wetter, warmer climate period from about 9,000 to 5,000 years ago, called the Holocene climatic optimum.

Early Dynastic Period :

The dynastic period begins c. 2900 BC and was associated with a shift from the temple establishment headed by council of elders led by a priestly "En" (a male figure when it was a temple for a goddess, or a female figure when headed by a male god) towards a more secular Lugal (Lu = man, Gal = great) and includes such legendary patriarchal figures as Dumuzid, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh—who reigned shortly before the historic record opens c. 2900 BC, when the now deciphered syllabic writing started to develop from the early pictograms. The center of Sumerian culture remained in southern Mesopotamia, even though rulers soon began expanding into neighboring areas, and neighboring Semitic groups adopted much of Sumerian culture for their own.

The earliest dynastic king on the Sumerian king list whose name is known from any other legendary source is Etana, 13th king of the first dynasty of Kish. The earliest king authenticated through archaeological evidence is Enmebaragesi of Kish (Early Dynastic I), whose name is also mentioned in the Gilgamesh epic—leading to the suggestion that Gilgamesh himself might have been a historical king of Uruk. As the Epic of Gilgamesh shows, this period was associated with increased war. Cities became walled, and increased in size as undefended villages in southern Mesopotamia disappeared. (Both Enmerkar and Gilgamesh are credited with having built the walls of Uruk).

1st Dynasty of Lagash :

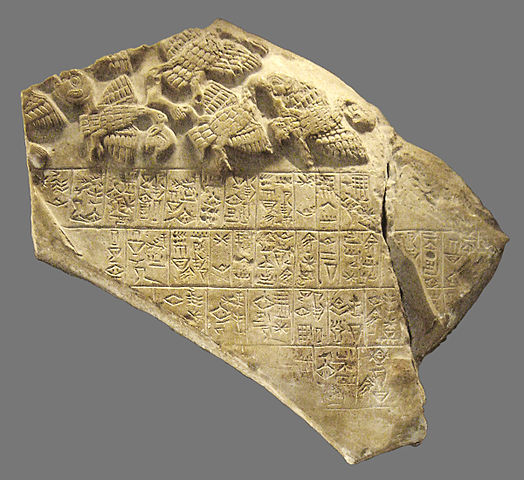

Fragment of Eannatum's Stele of the Vultures c. 2500 – 2270 BC :

The dynasty of Lagash, though omitted from the king list, is well attested through several important monuments and many archaeological finds.

Although short-lived, one of the first empires known to history was that of Eannatum of Lagash, who annexed practically all of Sumer, including Kish, Uruk, Ur, and Larsa, and reduced to tribute the city-state of Umma, arch-rival of Lagash. In addition, his realm extended to parts of Elam and along the Persian Gulf. He seems to have used terror as a matter of policy. Eannatum's Stele of the Vultures depicts vultures pecking at the severed heads and other body parts of his enemies. His empire collapsed shortly after his death.

Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean. He was the last ethnically Sumerian king before Sargon of Akkad.

Akkadian Empire :

The Akkadian Empire dates to c. 2234–2154 BC (Middle chronology). The Eastern Semitic Akkadian language is first attested in proper names of the kings of Kish c. 2800 BC, preserved in later king lists. There are texts written entirely in Old Akkadian dating from c. 2500 BC. Use of Old Akkadian was at its peak during the rule of Sargon the Great (c. 2334–2279 BC), but even then most administrative tablets continued to be written in Sumerian, the language used by the scribes. Gelb and Westenholz differentiate three stages of Old Akkadian: that of the pre-Sargonic era, that of the Akkadian empire, and that of the "Neo-Sumerian Renaissance" that followed it. Akkadian and Sumerian coexisted as vernacular languages for about one thousand years, but by around 1800 BC, Sumerian was becoming more of a literary language familiar mainly only to scholars and scribes. Thorkild Jacobsen has argued that there is little break in historical continuity between the pre- and post-Sargon periods, and that too much emphasis has been placed on the perception of a "Semitic vs. Sumerian" conflict. However, it is certain that Akkadian was also briefly imposed on neighboring parts of Elam that were previously conquered, by Sargon.

Gutian

period :

2nd Dynasty of Lagash :

Gudea of Lagash, the Sumerian ruler who was famous for his numerous portrait sculptures that have been recovered

Portrait of Ur-Ningirsu, son of Gudea, c. 2100 BC. Louvre Museum c. 2200–2110 BC (Middle chronology) :

Following the downfall of the Akkadian Empire at the hands of Gutians, another native Sumerian ruler, Gudea of Lagash, rose to local prominence and continued the practices of the Sargonid kings' claims to divinity. The previous Lagash dynasty, Gudea and his descendants also promoted artistic development and left a large number of archaeological artifacts.

"Neo-Sumerian" Ur III period :

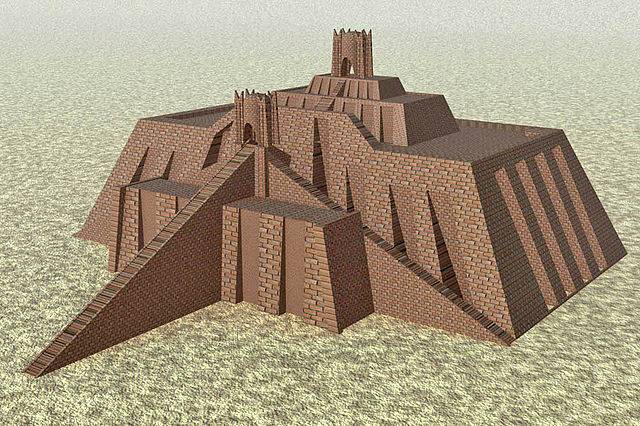

Great Ziggurat of Ur, c. 2100 BC, near Nasiriyah, Iraq c. 2112 – 2004 BC (Middle chronology) :

Later, the 3rd dynasty of Ur under Ur-Nammu and Shulgi, whose power extended as far as southern Assyria, was the last great "Sumerian renaissance". Already, however, the region was becoming more Semitic than Sumerian, with the resurgence of the Akkadian-speaking Semites in Assyria and elsewhere, and the influx of waves of Semitic Martu (Amorites), who were to found several competing local powers in the south, including Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna and, later ,Babylonia. The last of these eventually came to briefly dominate the south of Mesopotamia as the Babylonian Empire, just as the Old Assyrian Empire had already done in the north from the late 21st century BC. The Sumerian language continued as a sacerdotal language taught in schools in Babylonia and Assyria, much as Latin was used in the Medieval period, for as long as cuneiform was used.

Fall

and transmission :

Following an Elamite invasion and sack of Ur during the rule of Ibbi-Sin (c. 2028–2004 BC) [citation needed], Sumer came under Amorite rule (taken to introduce the Middle Bronze Age). The independent Amorite states of the 20th to 18th centuries are summarized as the "Dynasty of Isin" in the Sumerian king list, ending with the rise of Babylonia under Hammurabi c. 1800 BC.

Later rulers who dominated Assyria and Babylonia occasionally assumed the old Sargonic title "King of Sumer and Akkad", such as Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria after c. 1225 BC.

Population :

The first farmers from Samarra migrated to Sumer, and built shrines and settlements at Eridu Uruk, one of Sumer's largest cities, has been estimated to have had a population of 50,000–80,000 at its height; given the other cities in Sumer, and the large agricultural population, a rough estimate for Sumer's population might be 0.8 million to 1.5 million. The world population at this time has been estimated at about 27 million.

The Sumerians spoke a language isolate, but a number of linguists have claimed to be able to detect a substrate language of unknown classification beneath Sumerian because names of some of Sumer's major cities are not Sumerian, revealing influences of earlier inhabitants. However, the archaeological record shows clear uninterrupted cultural continuity from the time of the early Ubaid period (5300–4700 BC C-14) settlements in southern Mesopotamia. The Sumerian people who settled here farmed the lands in this region that were made fertile by silt deposited by the Tigris and the Euphrates.

Some archaeologists have speculated that the original speakers of ancient Sumerian may have been farmers, who moved down from the north of Mesopotamia after perfecting irrigation agriculture there. The Ubaid period pottery of southern Mesopotamia has been connected via Choga Mami transitional ware to the pottery of the Samarra period culture (c. 5700–4900 BC C-14) in the north, who were the first to practice a primitive form of irrigation agriculture along the middle Tigris River and its tributaries. The connection is most clearly seen at Tell Awayli (Oueilli, Oueili) near Larsa, excavated by the French in the 1980s, where eight levels yielded pre-Ubaid pottery resembling Samarran ware. According to this theory, farming peoples spread down into southern Mesopotamia because they had developed a temple-centered social organization for mobilizing labor and technology for water control, enabling them to survive and prosper in a difficult environment.[citation needed]

Others have suggested a continuity of Sumerians, from the indigenous hunter-fisherfolk traditions, associated with the bifacial assemblages found on the Arabian littoral. Juris Zarins believes the Sumerians may have been the people living in the Persian Gulf region before it flooded at the end of the last Ice Age.

Culture

:

A reconstruction in the British Museum of headgear and necklaces worn by the women at the Royal Cemetery at Ur In the early Sumerian period, the primitive pictograms suggest that

There is considerable evidence concerning Sumerian music. Lyres and flutes were played, among the best-known examples being the Lyres of Ur.

Inscriptions describing the reforms of king Urukagina of Lagash (c. 2350 BC) say that he abolished the former custom of polyandry in his country, prescribing that a woman who took multiple husbands be stoned with rocks upon which her crime had been written.

Sumerian princess (c. 2150 BC)

Sumerian princess of the time of Gudea c. 2150 BC

Frontal detail. Louvre Museum AO 295 The Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest such codification yet discovered, dating to the Ur III, reveals a glimpse at societal structure in late Sumerian law. Beneath the lu-gal ("great man" or king), all members of society belonged to one of two basic strata: The "lu" or free person, and the slave (male, arad; female geme). The son of a lu was called a dumu-nita until he married. A woman (munus) went from being a daughter (dumu-mi), to a wife (dam), then if she outlived her husband, a widow (numasu) and she could then remarry another man who was from the same tribe.[citation needed]

Marriages were usually arranged by the parents of the bride and groom; engagements were usually completed through the approval of contracts recorded on clay tablets. These marriages became legal as soon as the groom delivered a bridal gift to his bride's father.

Language and writing :

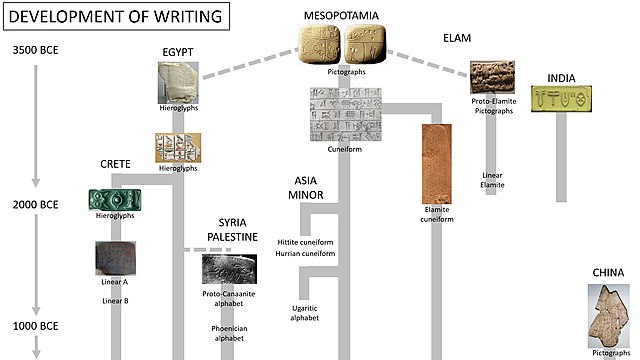

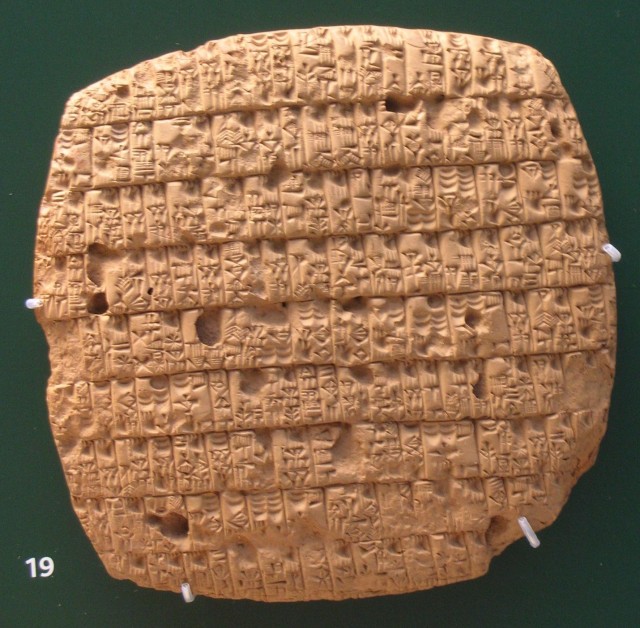

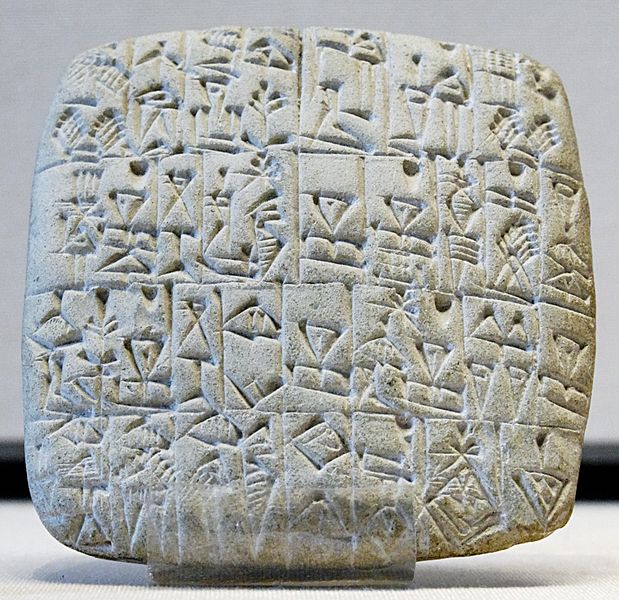

Standard reconstruction of the development of writing, showing Sumerian cuneiform at the origin of many writing systems The most important archaeological discoveries in Sumer are a large number of clay tablets written in cuneiform script. Sumerian writing is considered to be a great milestone in the development of humanity's ability to not only create historical records but also in creating pieces of literature, both in the form of poetic epics and stories as well as prayers and laws.

Although pictures—that is, hieroglyphs—were used first, cuneiform and then ideograms (where symbols were made to represent ideas) soon followed.

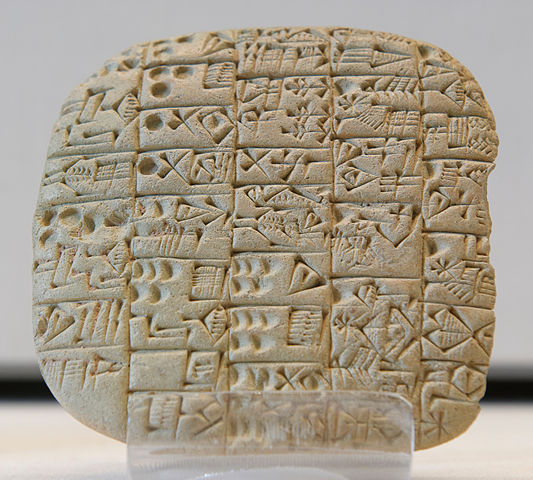

Triangular or wedge-shaped reeds were used to write on moist clay. A large body of hundreds of thousands of texts in the Sumerian language have survived, including personal and business letters, receipts, lexical lists, laws, hymns, prayers, stories, and daily records. Full libraries of clay tablets have been found. Monumental inscriptions and texts on different objects, like statues or bricks, are also very common. Many texts survive in multiple copies because they were repeatedly transcribed by scribes in training. Sumerian continued to be the language of religion and law in Mesopotamia long after Semitic speakers had become dominant.

A prime example of cuneiform writing would be a lengthy poem that was discovered in the ruins of Uruk. The Epic of Gilgamesh was written in the standard Sumerian cuneiform. It tells of a king from the early Dynastic II period named Gilgamesh or "Bilgamesh" in Sumerian. The story relates the fictional adventures of Gilgamesh and his companion, Enkidu. It was laid out on several clay tablets and is thought to be the earliest known surviving example of fictional literature.

The Sumerian language is generally regarded as a language isolate in linguistics because it belongs to no known language family; Akkadian, by contrast, belongs to the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic languages. There have been many failed attempts to connect Sumerian to other language families. It is an agglutinative language; in other words, morphemes ("units of meaning") are added together to create words, unlike analytic languages where morphemes are purely added together to create sentences. Some authors have proposed that there may be evidence of a substratum or adstratum language for geographic features and various crafts and agricultural activities, called variously Proto-Euphratean or Proto Tigrean, but this is disputed by others.

Understanding Sumerian texts today can be problematic. Most difficult are the earliest texts, which in many cases do not give the full grammatical structure of the language and seem to have been used as an "aide-mémoire" for knowledgeable scribes.

During the 3rd millennium BC, a cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism. The mutual influences between Sumerian on Akkadian are evident in all areas including lexical borrowing on a massive scale—and syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.These influences have prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian of the 3rd millennium BC as a Sprachbund.

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC, but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Babylonia and Assyria until the 1st century AD.

Early writing tablet for recording the allocation of beer; 3100 – 3000 BC; height: 9.4 cm; width: 6.87 cm; from Iraq; British Museum (London)

Cuneiform tablet about administrative account with entries concerning malt and barley groats; 3100 – 2900 BC; clay; 6.8 x 4.5 x 1.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Bill of sale of a field and house, from Shuruppak; c. 2600 BC; height: 8.5 cm, width: 8.5 cm, depth: 2 cm; Louvre

Stele of the Vultures; c. 2450 BC; limestone; found in 1881 by Édouard de Sarzec in Girsu (now Tell Telloh, Iraq); Louvre Religion :

Sumerian religion

Wall plaque showing libations to a seated god and a temple. Ur, 2500 BC

Naked priest offering libations to a Sumerian temple (detail), Ur, 2500 BC The Sumerians credited their divinities for all matters pertaining to them and exhibited humility in the face of cosmic forces, such as death and divine wrath.

Sumerian religion seems to have been founded upon two separate cosmogenic myths. The first saw creation as the result of a series of hieroi gamoi or sacred marriages, involving the reconciliation of opposites, postulated as a coming together of male and female divine beings, the gods.

This pattern continued to influence regional Mesopotamian myths. Thus, in the later Akkadian Enuma Elish, creation was seen as the union of fresh and salt water, between male Abzu, and female Tiamat. The products of that union, Lahm and Lahmu, "the muddy ones", were titles given to the gate keepers of the E-Abzu temple of Enki in Eridu, the first Sumerian city.

Mirroring the way that muddy islands emerge from the confluence of fresh and salty water at the mouth of the Euphrates, where the river deposits its load of silt, a second hieros gamos supposedly resulted in the creation of Anshar and Kishar, the "sky-pivot" (or axle), and the "earth pivot", parents in turn of Anu (the sky) and Ki (the earth).

Another important Sumerian hieros gamos was that between Ki, here known as Ninhursag or "Lady of the Mountains", and Enki of Eridu, the god of fresh water which brought forth greenery and pasture.

At an early stage, following the dawn of recorded history, Nippur, in central Mesopotamia, replaced Eridu in the south as the primary temple city, whose priests exercised political hegemony on the other city-states. Nippur retained this status throughout the Sumerian period.

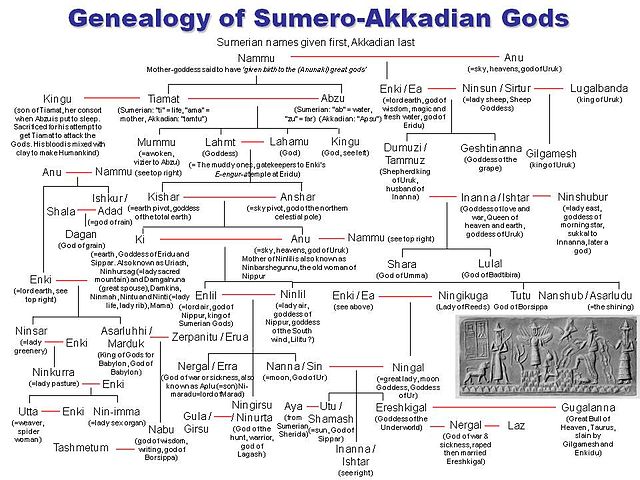

Deities :

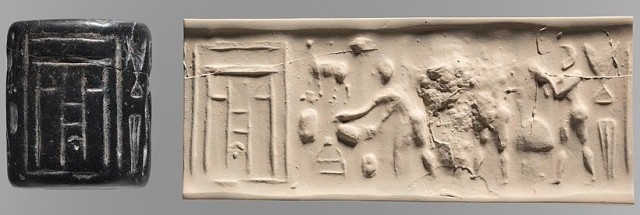

Akkadian cylinder seal from sometime around 2300 BC or thereabouts depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, Enki, and Isimud Sumerians believed in an anthropomorphic polytheism, or the belief in many gods in human form. There was no common set of gods; each city-state had its own patrons, temples, and priest-kings. Nonetheless, these were not exclusive; the gods of one city were often acknowledged elsewhere. Sumerian speakers were among the earliest people to record their beliefs in writing, and were a major inspiration in later Mesopotamian mythology, religion, and astrology.

The Sumerians worshiped :

Sumero-early Akkadian pantheon These deities formed a core pantheon; there were additionally hundreds of minor ones. Sumerian gods could thus have associations with different cities, and their religious importance often waxed and waned with those cities' political power. The gods were said to have created human beings from clay for the purpose of serving them. The temples organized the mass labour projects needed for irrigation agriculture. Citizens had a labor duty to the temple, though they could avoid it by a payment of silver.

Cosmology

:

The universe was divided into four quarters :

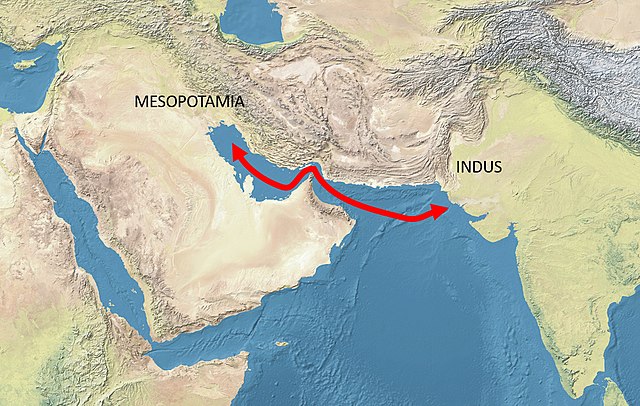

Their known world extended from The Upper Sea or Mediterranean coastline, to The Lower Sea, the Persian Gulf and the land of Meluhha (probably the Indus Valley) and Magan (Oman), famed for its copper ores.

Temple

and temple organisation :

Funerary

practices :

Agriculture

and hunting :

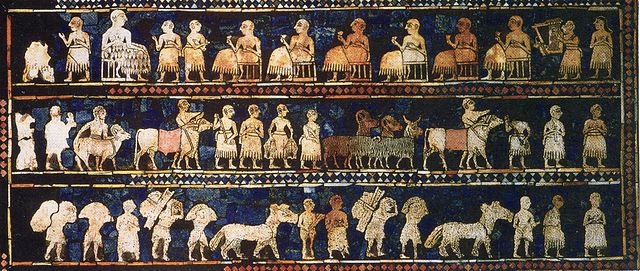

From the royal tombs of Ur, made of lapis lazuli and shell, shows peacetime In the early Sumerian Uruk period, the primitive pictograms suggest that sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs were domesticated. They used oxen as their primary beasts of burden and donkeys or equids as their primary transport animal and "woollen clothing as well as rugs were made from the wool or hair of the animals. ... By the side of the house was an enclosed garden planted with trees and other plants; wheat and probably other cereals were sown in the fields, and the shaduf was already employed for the purpose of irrigation. Plants were also grown in pots or vases."

An account of barley rations issued monthly to adults and children written in cuneiform script on a clay tablet, written in year 4 of King Urukagina, c. 2350 BC The Sumerians were one of the first known beer drinking societies. Cereals were plentiful and were the key ingredient in their early brew. They brewed multiple kinds of beer consisting of wheat, barley, and mixed grain beers. Beer brewing was very important to the Sumerians. It was referenced in the Epic of Gilgamesh when Enkidu was introduced to the food and beer of Gilgamesh's people: "Drink the beer, as is the custom of the land... He drank the beer-seven jugs! and became expansive and sang with joy!"

The Sumerians practiced similar irrigation techniques as those used in Egypt. American anthropologist Robert McCormick Adams says that irrigation development was associated with urbanization, and that 89% of the population lived in the cities.

They grew barley, chickpeas, lentils, wheat, dates, onions, garlic, lettuce, leeks and mustard. Sumerians caught many fish and hunted fowl and gazelle.

Sumerian agriculture depended heavily on irrigation. The irrigation was accomplished by the use of shaduf, canals, channels, dykes, weirs, and reservoirs. The frequent violent floods of the Tigris, and less so, of the Euphrates, meant that canals required frequent repair and continual removal of silt, and survey markers and boundary stones needed to be continually replaced. The government required individuals to work on the canals in a corvee, although the rich were able to exempt themselves.

As is known from the "Sumerian Farmer's Almanac", after the flood season and after the Spring equinox and the Akitu or New Year Festival, using the canals, farmers would flood their fields and then drain the water. Next they made oxen stomp the ground and kill weeds. They then dragged the fields with pickaxes. After drying, they plowed, harrowed, and raked the ground three times, and pulverized it with a mattock, before planting seed. Unfortunately, the high evaporation rate resulted in a gradual increase in the salinity of the fields. By the Ur III period, farmers had switched from wheat to the more salt-tolerant barley as their principal crop.

Sumerians harvested during the spring in three-person teams consisting of a reaper, a binder, and a sheaf handler. The farmers would use threshing wagons, driven by oxen, to separate the cereal heads from the stalks and then use threshing sleds to disengage the grain. They then winnowed the grain/chaff mixture.

Art :

The Sumerians were great creators, nothing proving this more than their art. Sumerian artifacts show great detail and ornamentation, with fine semi-precious stones imported from other lands, such as lapis lazuli, marble, and diorite, and precious metals like hammered gold, incorporated into the design. Since stone was rare it was reserved for sculpture. The most widespread material in Sumer was clay, as a result many Sumerian objects are made of clay. Metals such as gold, silver, copper, and bronze, along with shells and gemstones, were used for the finest sculpture and inlays. Small stones of all kinds, including more precious stones such as lapis lazuli, alabaster, and serpentine, were used for cylinder seals.

Some of the most famous masterpieces are the Lyres of Ur, which are considered to be the world's oldest surviving stringed instruments. They have been discovered by Leonard Woolley when the Royal Cemetery of Ur has been excavated between from 1922 and 1934.

Cylinder seal and impression in which appears a ritual scene before a temple façade; 3500 – 3100 BC; bituminous limestone; height: 4.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Ram in a Thicket; 2600 – 2400 BC; gold, copper, shell, lapis lazuli and limestone; height: 45.7 cm; from the Royal Cemetery at Ur (Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq); British Museum (London)

Standard of Ur; 2600 – 2400 BC; shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli on wood; length: 49.5 cm; from the Royal Cemetery at Ur; British Museum

Bull's head ornament from a lyre; 2600 – 2350 BC; bronze inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli; height: 13.3 cm, width: 10.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Architecture :

The Tigris-Euphrates plain lacked minerals and trees. Sumerian structures were made of plano-convex mudbrick, not fixed with mortar or cement. Mud-brick buildings eventually deteriorate, so they were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This constant rebuilding gradually raised the level of cities, which thus came to be elevated above the surrounding plain. The resultant hills, known as tells, are found throughout the ancient Near East.

According to Archibald Sayce, the primitive pictograms of the early Sumerian (i.e. Uruk) era suggest that "Stone was scarce, but was already cut into blocks and seals. Brick was the ordinary building material, and with it cities, forts, temples and houses were constructed. The city was provided with towers and stood on an artificial platform; the house also had a tower-like appearance. It was provided with a door which turned on a hinge, and could be opened with a sort of key; the city gate was on a larger scale, and seems to have been double. The foundation stones—or rather bricks—of a house were consecrated by certain objects that were deposited under them."

The most impressive and famous of Sumerian buildings are the ziggurats, large layered platforms that supported temples. Sumerian cylinder seals also depict houses built from reeds not unlike those built by the Marsh Arabs of Southern Iraq until as recently as 400 CE. The Sumerians also developed the arch, which enabled them to develop a strong type of dome. They built this by constructing and linking several arches. Sumerian temples and palaces made use of more advanced materials and techniques, such as buttresses, recesses, half columns, and clay nails.

Mathematics

:

Economy and trade :

Bill of sale of a male slave and a building in Shuruppak, Sumerian tablet, c. 2600 BC Discoveries of obsidian from far-away locations in Anatolia and lapis lazuli from Badakhshan in northeastern Afghanistan, beads from Dilmun (modern Bahrain), and several seals inscribed with the Indus Valley script suggest a remarkably wide-ranging network of ancient trade centered on the Persian Gulf. For example, Imports to Ur came from many parts of the world. In particular, the metals of all types had to be imported.

The Epic of Gilgamesh refers to trade with far lands for goods, such as wood, that were scarce in Mesopotamia. In particular, cedar from Lebanon was prized. The finding of resin in the tomb of Queen Puabi at Ur, indicates it was traded from as far away as Mozambique.

The Sumerians used slaves, although they were not a major part of the economy. Slave women worked as weavers, pressers, millers, and porters.[citation needed]

Sumerian potters decorated pots with cedar oil paints. The potters used a bow drill to produce the fire needed for baking the pottery. Sumerian masons and jewelers knew and made use of alabaster (calcite), ivory, iron, gold, silver, carnelian, and lapis lazuli.

Trade with the Indus valley :

The trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus would have been significantly shorter due to lower sea levels in the 3rd millennium BC Evidence for imports from the Indus to Ur can be found from around 2350 BC. Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularly Trubinella Pyrum and Fasciolaria Trapezium, have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500–2000 BC. Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in the Sumerian tombs of Ur, the Royal Cemetery at Ur, dating to 2600–2450. In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique of acid-etching developed by the Harappans. Lapis lazuli was imported in great quantity by Egypt, and already used in many tombs of the Naqada II period (c. 3200 BC). Lapis Lazuli probably originated in northern Afghanistan, as no other sources are known, and had to be transported across the Iranian plateau to Mesopotamia, and then Egypt.

Several Indus seals with Harappan script have also been found in Mesopotamia, particularly in Ur, Babylon and Kish.

Gudea, the ruler of the Neo-Summerian Empire at Lagash, is recorded as having imported "translucent carnelian" from Meluhha, generally thought to be the Indus Valley area. Various inscriptions also mention the presence of Meluhha traders and interpreters in Mesopotamia. About twenty seals have been found from the Akkadian and Ur III sites, that have connections with Harappa and often use Harappan symbols or writing.

The Indus Valley Civilization only flourished in its most developed form between 2400 and 1800 BC, but at the time of these exchanges, it was a much larger entity than the Mesopotamian civilization, covering an area of 1.2 million square meters with thousands of settlements, compared to an area of only about 65.000 square meters for the occupied area of Mesopotamia, while the largest cities were comparable in size at about 30–40,000 inhabitants.

Money

and credit :

Commercial credit and agricultural consumer loans were the main types of loans. The trade credit was usually extended by temples in order to finance trade expeditions and was nominated in silver. The interest rate was set at 1/60 a month (one shekel per mina) some time before 2000 BC and it remained at that level for about two thousand years. Rural loans commonly arose as a result of unpaid obligations due to an institution (such as a temple), in this case the arrears were considered to be lent to the debtor. They were denominated in barley or other crops and the interest rate was typically much higher than for commercial loans and could amount to 1/3 to 1/2 of the loan principal.

Periodically, rulers signed "clean slate" decrees that cancelled all the rural (but not commercial) debt and allowed bondservants to return to their homes. Customarily, rulers did it at the beginning of the first full year of their reign, but they could also be proclaimed at times of military conflict or crop failure. The first known ones were made by Enmetena and Urukagina of Lagash in 2400–2350 BC. According to Hudson, the purpose of these decrees was to prevent debts mounting to a degree that they threatened the fighting force, which could happen if peasants lost their subsistence land or became bondservants due to inability to repay their debt.

Military :

Early chariots on the Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BC

Phalanx battle formations led by Sumerian king Eannatum, on a fragment of the Stele of the Vultures

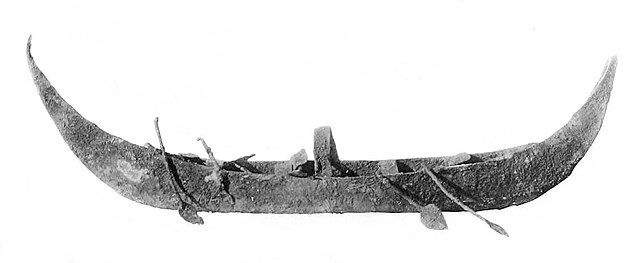

Silver model of a boat, tomb PG 789, Royal Cemetery of Ur, 2600 – 2500 BC The almost constant wars among the Sumerian city-states for 2000 years helped to develop the military technology and techniques of Sumer to a high level. The first war recorded in any detail was between Lagash and Umma in c. 2450 BC on a stele called the Stele of the Vultures. It shows the king of Lagash leading a Sumerian army consisting mostly of infantry. The infantry carried spears, wore copper helmets, and carried rectangular shields. The spearmen are shown arranged in what resembles the phalanx formation, which requires training and discipline; this implies that the Sumerians may have made use of professional soldiers.

The Sumerian military used carts harnessed to onagers. These early chariots functioned less effectively in combat than did later designs, and some have suggested that these chariots served primarily as transports, though the crew carried battle-axes and lances. The Sumerian chariot comprised a four or two-wheeled device manned by a crew of two and harnessed to four onagers. The cart was composed of a woven basket and the wheels had a solid three-piece design.

Sumerian cities were surrounded by defensive walls. The Sumerians engaged in siege warfare between their cities, but the mudbrick walls were able to deter some foes.

Technology

:

Legacy :

Map of Sumer Evidence of wheeled vehicles appeared in the mid 4th millennium BC, near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus (Maykop culture) and Central Europe. The wheel initially took the form of the potter's wheel. The new concept led to wheeled vehicles and mill wheels. The Sumerians' cuneiform script is the oldest (or second oldest after the Egyptian hieroglyphs) which has been deciphered (the status of even older inscriptions such as the Jiahu symbols and Tartaria tablets is controversial). The Sumerians were among the first astronomers, mapping the stars into sets of constellations, many of which survived in the zodiac and were also recognized by the ancient Greeks. They were also aware of the five planets that are easily visible to the naked eye.

They invented and developed arithmetic by using several different number systems including a mixed radix system with an alternating base 10 and base 6. This sexagesimal system became the standard number system in Sumer and Babylonia. They may have invented military formations and introduced the basic divisions between infantry, cavalry, and archers. They developed the first known codified legal and administrative systems, complete with courts, jails, and government records. The first true city-states arose in Sumer, roughly contemporaneously with similar entities in what are now Syria and Lebanon. Several centuries after the invention of cuneiform, the use of writing expanded beyond debt/payment certificates and inventory lists to be applied for the first time, about 2600 BC, to messages and mail delivery, history, legend, mathematics, astronomical records, and other pursuits. Conjointly with the spread of writing, the first formal schools were established, usually under the auspices of a city-state's primary temple.

Hungarian-Sumerian

hypothesis :

The hypothesis had more popularity among Sumerologists in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Nowadays, it is mostly dismissed, although it is acknowledged that Sumerian is an agglutinative language, just like the Hungarian, Turkish and Finnish languages and regarding linguistic structure resembles these and some Caucasian languages; however in vocabulary, grammar, and syntax Sumerian still stands alone and seems to be unrelated to any other language, living or dead.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)

_(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)