| URUK

Uruk

Uruk in 2008

Uruk (Cuneiform: unugki, Akkadian: Uruk (URUUNUG); Arabic: Warka' or Auruk; Syriac: ‘Úruk; Hebrew: 'Érek; Romanized: Orkhóe, Orékh, Orúgeia) was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthanna, Iraq.

Uruk is the type site for the Uruk period. Uruk played a leading role in the early urbanization of Sumer in the mid-4th millennium BC. By the final phase of the Uruk period around 3100 BC, the city may have had 40,000 residents, with 80,000-90,000 people living in its environs, making it the largest urban area in the world at the time. The legendary king Gilgamesh, according to the chronology presented in the Sumerian King List (henceforth SKL), ruled Uruk in the 27th century BC. The city lost its prime importance around 2000 BC in the context of the struggle of Babylonia against Elam, but it remained inhabited throughout the Seleucid (312–63 BC) and Parthian (227 BC to 224 AD) periods until it was finally abandoned shortly before or after the Islamic conquest of 633–638.

William Kennett Loftus visited the site of Uruk in 1849, identifying it as "Erech", known as "the second city of Nimrod", and led the first excavations from 1850 to 1854.

The Arabic name of the present-day country, al-Iraq cannot derive from the name Uruk, but is loaned via Middle Persian (Eraq) and then Aramaic ’yrg transmission.

Prominence :

Uruk expansion and colonial outposts, c. 3600 - 3200 BC In myth and literature, Uruk was famous as the capital city of Gilgamesh, hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Scholars identify Uruk as the biblical Erech (Genesis 10:10), the second city founded by Nimrod in Shinar.

Uruk

period :

Geographic factors :

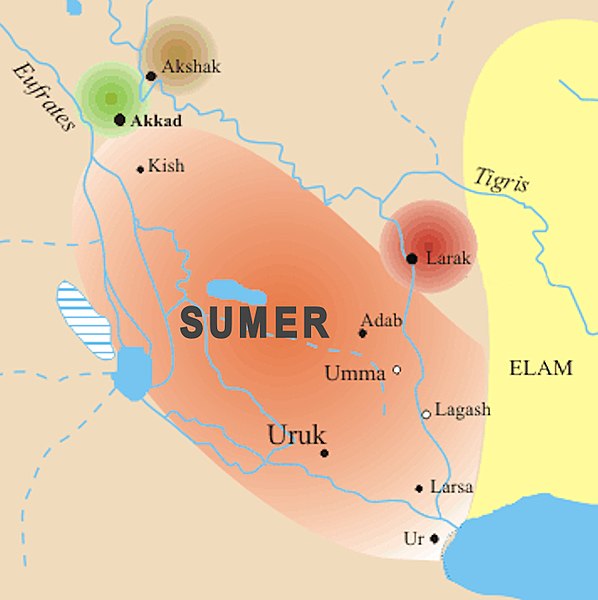

Map of Sumer Geographic factors underpin Uruk's unprecedented growth. The city was located in the southern part of Mesopotamia, an ancient site of civilization, on the Euphrates river. Through the gradual and eventual domestication of native grains from the Zagros foothills and extensive irrigation techniques, the area supported a vast variety of edible vegetation. This domestication of grain and its proximity to rivers enabled Uruk's growth into the largest Sumerian settlement, in both population and area, with relative ease.

Uruk's agricultural surplus and large population base facilitated processes such as trade, specialization of crafts and the evolution of writing; writing may have originated in Uruk around 3300 BC. Evidence from excavations such as extensive pottery and the earliest known tablets of writing support these events. Excavation of Uruk is highly complex because older buildings were recycled into newer ones, thus blurring the layers of different historic periods. The topmost layer most likely originated in the Jemdet Nasr period (3100–2900 BC) and is built on structures from earlier periods dating back to the Ubaid period.

History :

Devotional scene to Inanna, Warka Vase, c. 3200 – 3000 BC, Uruk. This is one of the earliest surviving works of narrative relief sculpture According to the SKL, Uruk was founded by the king Enmerkar. Though the king-list mentions a king of Eanna before him, the epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta relates that Enmerkar constructed the House of Heaven (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: E2.AN) for the goddess Inanna in the Eanna District of Uruk. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh builds the city wall around Uruk and is king of the city.

Uruk went through several phases of growth, from the Early Uruk period (4000–3500 BC) to the Late Uruk period (3500–3100 BC). The city was formed when two smaller Ubaid settlements merged. The temple complexes at their cores became the Eanna District and the Anu District dedicated to Inanna and Anu, respectively. The Anu District was originally called 'Kullaba' (Kulab or Unug-Kulaba) prior to merging with the Eanna District. Kullaba dates to the Eridu period when it was one of the oldest and most important cities of Sumer. There are different interpretations about the purposes of the temples. However, it is generally believed they were a unifying feature of the city. It also seems clear that temples served both an important religious function and state function. The surviving temple archive of the Neo-Babylonian period documents the social function of the temple as a redistribution center.

The Eanna District was composed of several buildings with spaces for workshops, and it was walled off from the city. By contrast, the Anu District was built on a terrace with a temple at the top. It is clear Eanna was dedicated to Inanna from the earliest Uruk period throughout the history of the city. The rest of the city was composed of typical courtyard houses, grouped by profession of the occupants, in districts around Eanna and Anu. Uruk was extremely well penetrated by a canal system that has been described as, "Venice in the desert." This canal system flowed throughout the city connecting it with the maritime trade on the ancient Euphrates River as well as the surrounding agricultural belt.

The original city of Uruk was situated southwest of the ancient Euphrates River, now dry. Currently, the site of Warka is northeast of the modern Euphrates river. The change in position was caused by a shift in the Euphrates at some point in history, which, together with salination due to irrigation, may have contributed to the decline of Uruk.

Archaeological

levels of Uruk :

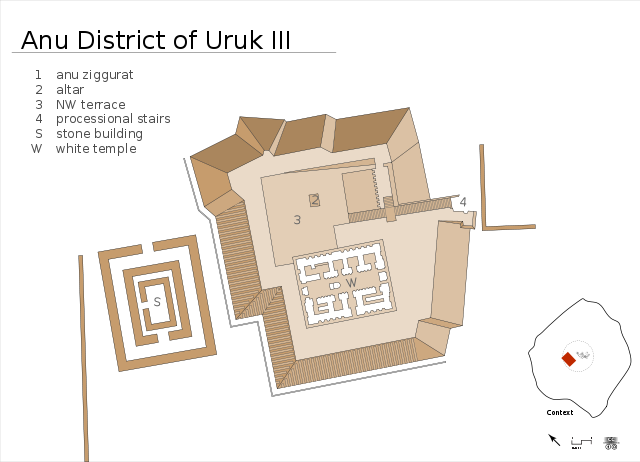

Anu district : Anu/ White Temple ziggurat

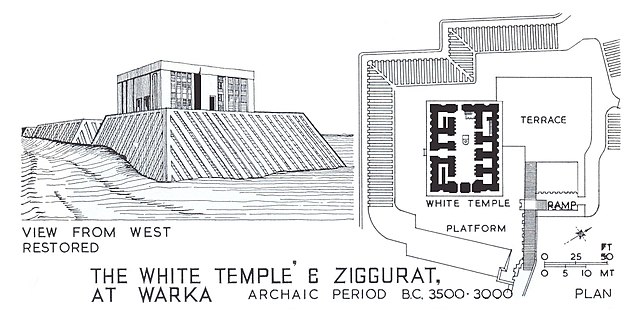

Anu/ White Temple ziggurat at Uruk. The original pyramidal structure, the "Anu Ziggurat" dates to around 4000 BCE, and the White Temple was built on top of it circa 3500 BCE The great Anu district is older than the Eanna district; however, few remains of writing have been found here. Unlike the Eanna district, the Anu district consists of a single massive terrace, the Anu Ziggurat, dedicated to the Sumerian sky god Anu. Sometime in the Uruk III period the massive White Temple was built atop of the ziggurat. Under the northwest edge of the ziggurat an Uruk VI period structure, the Stone Temple, has been discovered.

The Stone Temple was built of limestone and bitumen on a podium of rammed earth and plastered with lime mortar. The podium itself was built over a woven reed mat called gipar, which was ritually as used a nuptial bed. The gipar was a source of generative power which then radiated upward into the structure. The structure of the Stone Temple further develops some mythological concepts from Enuma Elish, perhaps involving libation rites as indicated from the channels, tanks, and vessels found there. The structure was ritually destroyed, covered with alternating layers of clay and stone, then excavated and filled with mortar sometime later.

The Anu Ziggurat began with a massive mound topped by a cella during the Uruk period (ca. 4000 BC), and was expanded through 14 phases of construction. These phases have been labeled L to A3 (L is sometimes called X). The earliest phase used architectural features similar to PPNA cultures in Anatolia: a single chamber cella with a terazzo floor beneath which bucrania were found. In phase E, corresponding to the Uruk III period (ca. 3000 BC), the White Temple was built. The White Temple could be seen from a great distance across the plain of Sumer, as it was elevated 21m and covered in gypsum plaster which reflected sunlight like a mirror. For this reason it is believed the White Temple is a symbol of Uruk's political power at the time. [citation needed] In addition to this temple the Anu Ziggurat had a monumental limestone-paved staircase, which was used in religious processions. A trough running parallel to the staircase was used to drain the ziggurat.

Eanna district :

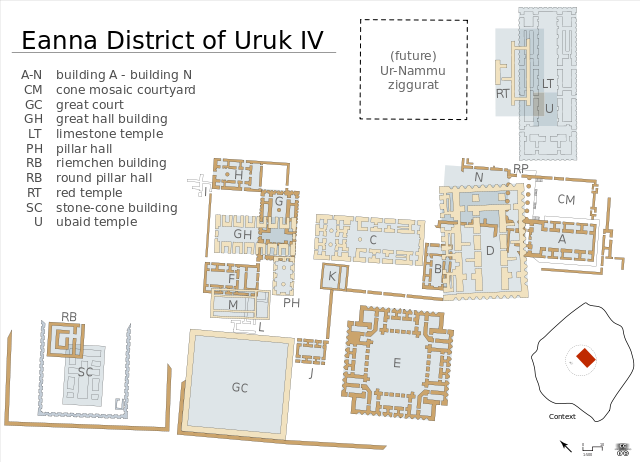

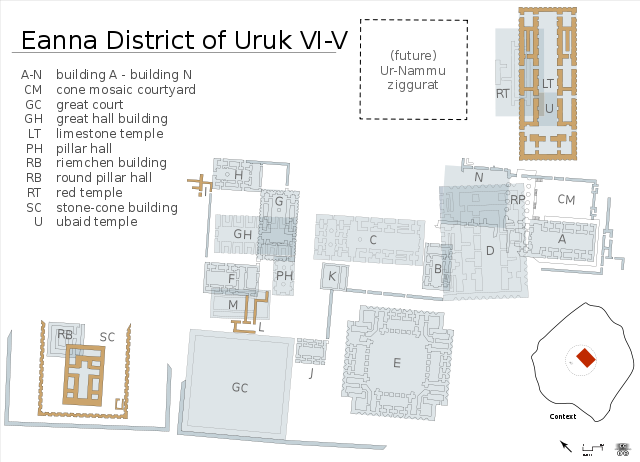

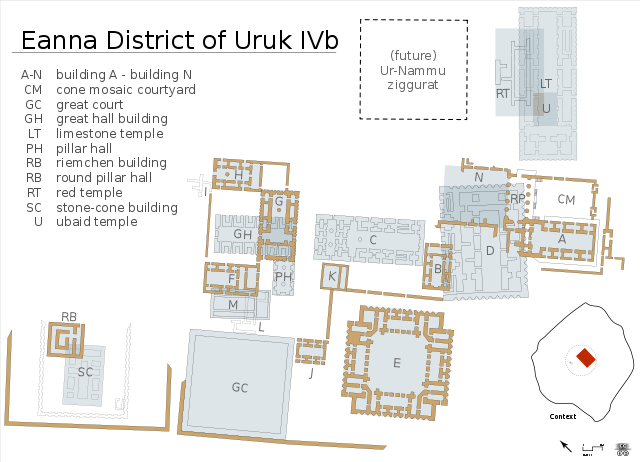

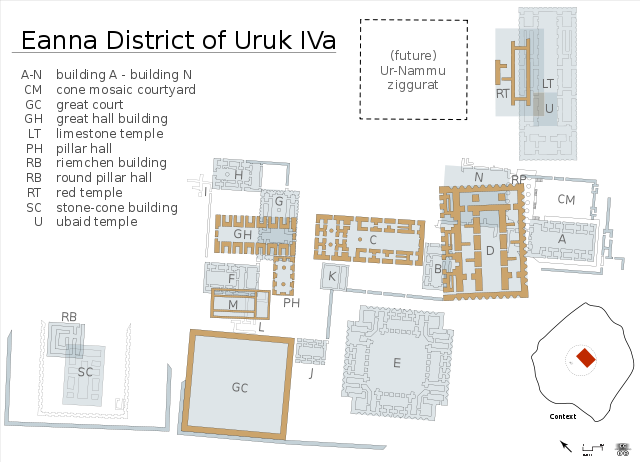

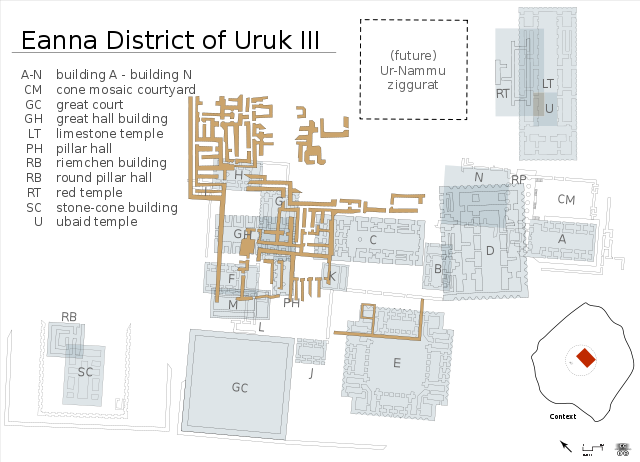

Eanna IVa (light brown) and IVb (dark brown) The Eanna district is historically significant as both writing and monumental public architecture emerged here during Uruk periods VI-IV. The combination of these two developments places Eanna as arguably the first true city and civilization in human history. Eanna during period IVa contains the earliest examples of cuneiform writing and possibly the earliest writing in history. Although some of these cuneiform tablets have been deciphered, difficulty with site excavations has obscured the purpose and sometimes even the structure of many buildings.

The first building of Eanna, Stone-Cone Temple (Mosaic Temple), was built in period VI over a preexisting Ubaid temple and is enclosed by a limestone wall with an elaborate system of buttresses. The Stone-Cone Temple, named for the mosaic of colored stone cones driven into the adobe brick façade, may be the earliest water cult in Mesopotamia. It was ritually demolished in Uruk IVb period and its contents interred in the Riemchen Building.

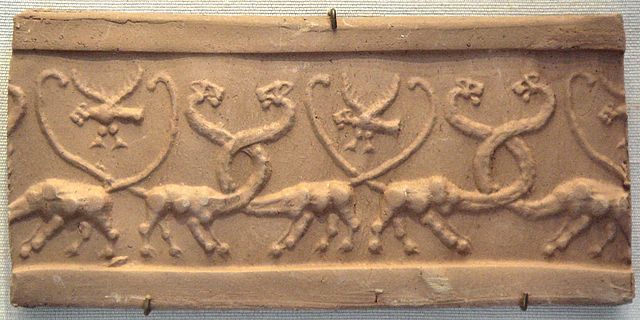

An Uruk period cylinder-seal and its impression, c. 3100 BC. Louvre In the following period, Uruk V, about 100 m east of the Stone-Cone Temple the Limestone Temple was built on a 2 m high rammed-earth podium over a pre-existing Ubaid temple, which like the Stone-Cone Temple represents a continuation of Ubaid culture. However, the Limestone Temple was unprecedented for its size and use of stone, a clear departure from traditional Ubaid architecture. The stone was quarried from an outcrop at Umayyad about 60 km east of Uruk. It is unclear if the entire temple or just the foundation was built of this limestone. The Limestone temple is probably the first Inanna temple, but it is impossible to know with certainty. Like the Stone-Cone temple the Limestone temple was also covered in cone mosaics. Both of these temples were rectangles with their corners aligned to the cardinal directions, a central hall flanked along the long axis flanked by two smaller halls, and buttressed façades; the prototype of all future Mesopotamian temple architectural typology.

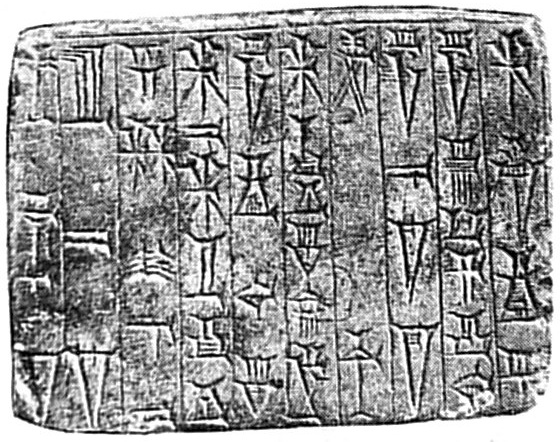

Tablet from Uruk III (c. 3200 – 3000 BC) recording beer distributions from the storerooms of an institution, British Museum Between these two monumental structures a complex of buildings (called A-C, E-K, Riemchen, Cone-Mosaic), courts, and walls was built during Eanna IVb. These buildings were built during a time of great expansion in Uruk as the city grew to 250 hectares and established long-distance trade, and are a continuation of architecture from the previous period. The Riemchen Building, named for the 16×16 cm brick shape called Riemchen by the Germans, is a memorial with a ritual fire kept burning in the center for the Stone-Cone Temple after it was destroyed. For this reason, Uruk IV period represents a reorientation of belief and culture. The facade of this memorial may have been covered in geometric and figural murals. The Riemchen bricks first used in this temple were used to construct all buildings of Uruk IV period Eanna. The use of colored cones as a façade treatment was greatly developed as well, perhaps used to greatest effect in the Cone-Mosaic Temple. Composed of three parts: Temple N, the Round Pillar Hall, and the Cone-Mosaic Courtyard, this temple was the most monumental structure of Eanna at the time. They were all ritually destroyed and the entire Eanna district was rebuilt in period IVa at an even grander scale.

During Eanna IVa, the Limestone Temple was demolished and the Red Temple built on its foundations. The accumulated debris of the Uruk IVb buildings were formed into a terrace, the L-Shaped Terrace, on which Buildings C, D, M, Great Hall, and Pillar Hall were built. Building E was initially thought to be a palace, but later proven to be a communal building. Also in period IV, the Great Court, a sunken courtyard surrounded by two tiers of benches covered in cone mosaic, was built. A small aqueduct drains into the Great Courtyard, which may have irrigated a garden at one time. The impressive buildings of this period were built as Uruk reached its zenith and expanded to 600 hectares. All the buildings of Eanna IVa were destroyed sometime in Uruk III, for unclear reasons.

The architecture of Eanna in period III was very different from what had preceded it. The complex of monumental temples was replaced with baths around the Great Courtyard and the labyrinthine Rammed-Earth Building. This period corresponds to Early Dynastic Sumer c 2900 BC, a time of great social upheaval when the dominance of Uruk was eclipsed by competing city-states. The fortress-like architecture of this time is a reflection of that turmoil. The temple of Inanna continued functioning during this time in a new form and under a new name, 'The House of Inanna in Uruk' (Sumerian: e2-dinanna unuki-ga). The location of this structure is currently unknown.

Uruk

into Late Antiquity :

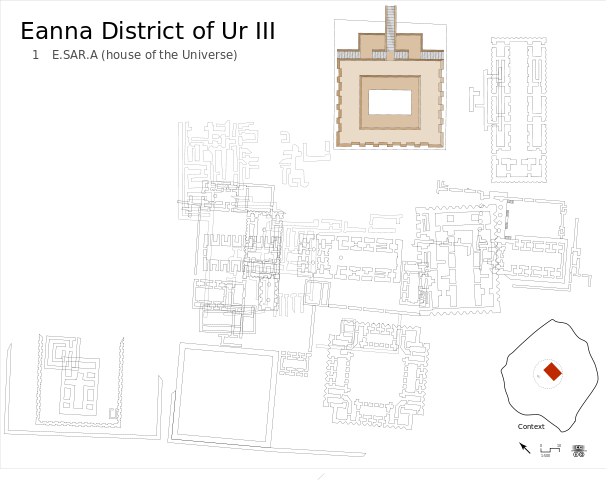

Partially reconstructed facade and access staircase of the Ziggurat of Ur, originally built by Ur-Nammu, Neo-Sumerian period, circa 2100 BCE The ziggurat is also cited as Ur-Nammu Ziggurat for its builder Ur-Nammu. Following the collapse of Ur (c 2000 BC), Uruk went into a steep decline until about 850 BC when the Neo-Assyrian Empire annexed it as a provincial capital. Under the Neo-Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians, Uruk regained much of its former glory. By 250 BC, a new temple complex the 'Head Temple' (Akkadian: Bit Reš) was added to northeast of the Uruk period Anu district. The Bit Reš along with the Esagila was one of the two main centers of Neo-Babylonian astronomy. All of the temples and canals were restored again under Nabopolassar. During this era, Uruk was divided into five main districts: the Adad Temple, Royal Orchard, Ištar Gate, Lugalirra Temple, and Šamaš Gate districts.

Uruk, known as Orcha to the Greeks, continued to thrive under the Seleucid Empire. During this period, Uruk was a city of 300 hectares and perhaps 40,000 inhabitants. In 200 BC, the 'Great Sanctuary' (Cuneiform: E2.IRI12.GAL, Sumerian: eš-gal) of Ishtar was added between the Anu and Eanna districts. The ziggurat of the temple of Anu, which was rebuilt in this period, was the largest ever built in Mesopotamia. When the Seleucids lost Mesopotamia to the Parthians in 141 BC, Uruk again entered a period of decline from which it never recovered. The decline of Uruk may have been in part caused by a shift in the Euphrates River. By 300 AD, Uruk was mostly abandoned, but a group of Mandaeans settled there, and by c 700 AD it was completely abandoned.

Political history :

Uruk King-Priest Mesopotamian king as Master of Animals on the Gebel el-Arak Knife (c. 3300-3200 BC, Abydos, Egypt), a work indicating Egypt-Mesopotamia relations and showing the early influence of Mesopotamia on Egypt and the state of Mesopotamian royal iconography in the Uruk period. Louvre.

Probable Uruk King-Priest with a beard and hat (c. 3300 BC, Uruk). Louvre

"In Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, Sumerian civilization

seems to have reached its creative peak. This is pointed out repeatedly

in the references to this city in religious and, especially, in

literary texts, including those of mythological content; the historical

tradition as preserved in the Sumerian king-list confirms it.

From Uruk the center of political gravity seems to have moved

to Ur."

Uruk played a very important part in the political history of Sumer. Starting from the Early Uruk period, the city exercised hegemony over nearby settlements. At this time (c 3800 BC), there were two centers of 20 hectares, Uruk in the south and Nippur in the north surrounded by much smaller 10 hectare settlements. Later, in the Late Uruk period, its sphere of influence extended over all Sumer and beyond to external colonies in upper Mesopotamia and Syria. Uruk was prominent in the national struggles of the Sumerians against the Elamites up to 2004 BC, in which it suffered severely; recollections of some of these conflicts are embodied in the Gilgamesh epic, in the literary and courtly form.

The recorded chronology of rulers over Uruk includes both mythological and historic figures in five dynasties. As in the rest of Sumer, power moved progressively from the temple to the palace. Rulers from the Early Dynastic period exercised control over Uruk and at times over all Sumer. In myth, kingship was lowered from heaven to Eridu then passed successively through five cities until the deluge which ended the Uruk period. Afterwards, kingship passed to Kish at the beginning of the Early Dynastic period, which corresponds to the beginning of the Early Bronze Age in Sumer. In the Early Dynastic I period (2900–2800 BC), Uruk was in theory under the control of Kish. This period is sometimes called the Golden Age. During the Early Dynastic II period (2800–2600 BC), Uruk was again the dominant city exercising control of Sumer. This period is the time of the First Dynasty of Uruk sometimes called the Heroic Age. However, by the Early Dynastic IIIa period (2600–2500 BC) Uruk had lost sovereignty, this time to Ur. This period, corresponding to the Early Bronze Age III, is the end of the First Dynasty of Uruk. In the Early Dynastic IIIb period (2500–2334 BC), also called the Pre-Sargonic period (referring to Sargon of Akkad), Uruk continued to be ruled by Ur.

Early dynastic, Akkadian, and Neo-Sumerian rulers of Uruk :

Clay impression of a cylinder seal with monstrous lions and lion-headed eagles, Mesopotamia, Uruk Period (4100 BC – 3000 BC). Louvre Museum

Foundation peg of Lugal-kisal-si, king of Uruk, Ur and Kish, circa 2380 BCE. The inscription reads "For (goddess) Namma, wife of (the god) An, Lugalkisalsi, King of Uruk, King of Ur, erected this temple of Namma". Pergamon Museum VA 4855.

Dedication tablet of Sîn-gamil, ruler of Uruk, 18th century BCE Dynastic categorizations should be considered arbitrary, as they are only known from the SKL, which is of dubious historical accuracy; the organization might be analogous to Manetho's. The following list should not be considered complete.

In 2009, two different copies of an inscription were put forth as evidence of a 19th-century BC ruler of Uruk named Naram-sin.

Uruk continued as principality of Ur, Babylon, and later Achaemenid, Seleucid, and Parthian Empires. It enjoyed brief periods of independence during the Isin-Larsa period, under kings such as (possibly) Ikun-pî-Ištar (c. 1800 BC), Sîn-kašid, his son Sîn-iribam, his son Sîn-gamil, Ilum-gamil, brother of Sîn-gamil, Eteia, Anam, ÌR-ne-ne, who was defeated by Rim-Sîn I of Larsa in his year 14 (c. 1740 BC), Rim-Anum and Nabi-ilišu. The city was finally destroyed by the Arab invasion of Mesopotamia and abandoned c. 700 AD.

Architecture :

Relief on the front of the Inanna temple of Karaindash from Uruk. Mid 15th century BC. Pergamon Museum, Berlin

Male deity pouring a life-giving water from a vessel. Facade of Inanna Temple at Uruk, Iraq. 15th century BC. The Pergamon Museum

The Parthian Temple of Charyios at Uruk

It is clear Eanna was dedicated to Inanna symbolized by Venus from the Uruk period. At that time, she was worshipped in four aspects as Inanna of the netherworld (Sumerian: dinanna-kur), Inanna of the morning (Sumerian: dinanna-hud2), Inanna of the evening (Sumerian: dinanna-sig), and Inanna (Sumerian: dinanna-NUN). The names of four temples in Uruk at this time are known, but it is impossible to match them with either a specific structure and in some cases a deity.

Architecture of Uruk

Plan of Eanna VI-V

Plan of Eanna IVb

Plan of Eanna IVa

Plan of Eanna III

Plan of Neo-Sumerian Eanna

Plan of Anu District Phase E

Reconstruction of a mosaic from the Eanna temple

Detail of Reconstruction of a mosaic from the Eanna temple Archaeology :

Mesopotamia

in the 2nd millennium BC. From north to south: Nineveh, Qattara

(or Karana), Dur-Katlimmu, Assur, Arrapha, Terqa, Nuzi, Mari,

Eshnunna, Dur-Kurigalzu, Der, Sippar, Babylon, Kish, Susa, Borsippa,

Nippur, Isin, Uruk, Larsa and Ur.

The location of Uruk was first scouted by William Loftus in 1849. He excavated there in 1850 and 1854. By Loftus' own account, he admits that the first excavations were superficial at best, as his financiers forced him to deliver large museum artifacts at a minimal cost. Warka was also scouted by archaeologist Walter Andrae in 1902.

From 1912 to 1913, Julius Jordan and his team from the German Oriental Society discovered the temple of Ishtar, one of four known temples located at the site. The temples at Uruk were quite remarkable as they were constructed with brick and adorned with colorful mosaics. Jordan also discovered part of the city wall. It was later discovered that this 40-to-50-foot (12 to 15 m) high brick wall, probably utilized as a defense mechanism, totally encompassed the city at a length of 9 km (5.6 mi). Utilizing sedimentary strata dating techniques, this wall is estimated to have been erected around 3000 BC. The GOS returned to Uruk in 1928 and excavated until 1939, when World War II intervened. The team was led by Jordan until 1931, then by A. Nöldeke, Ernst Heinrich, and H. J. Lenzen.

The German excavations resumed after the war and were under the direction of Heinrich Lenzen from 1953 to 1967. He was followed in 1968 by J. Schmidt, and in 1978 by R.M. Boehmer. In total, the German archaeologists spent 39 seasons working at Uruk. The results are documented in two series of reports :

Most recently, from 2001 to 2002, the German Archaeological Institute team led by Margarete van Ess, with Joerg Fassbinder and Helmut Becker, conducted a partial magnetometer survey in Uruk. In addition to the geophysical survey, core samples and aerial photographs were taken. This was followed up with high-resolution satellite imagery in 2005.

Clay tablets have been found at Uruk with Sumerian and pictorial inscriptions that are thought to be some of the earliest recorded writing, dating to approximately 3300 BC. These tablets were deciphered and include the famous SKL, a record of kings of the Sumerian civilization. There was an even larger cache of legal and scholarly tablets of the Neo-Babylonian, Late Babylonian, and Seleucid period, that have been published by Adam Falkenstein and other Assyriological members of the German Archaeological Institute in Baghdad as Jan J. A. Djik, Hermann Hunger, Antoine Cavigneaux, Egbert von Weiher, and Karlheinz Kessler, or others as Erlend Gehlken. Many of the cuneiform tablets form acquisitions by museums and collections as the British Museum, Yale Babylonian Collection, and the Louvre. The later holds a unique cuneiform tablet in Aramaic known as the Aramaic Uruk incantation.

Late Uruk Period beveled rim bowls used for ration distribution Beveled rim bowls were the most common type of container used during the Uruk period. They are believed to be vessels for serving rations of food or drink to dependent laborers. The introduction of the fast wheel for throwing pottery was developed during the later part of the Uruk period, and made the mass production of pottery simpler and more standardized.

Artifacts

:

Lugal-kisal-si, king of Uruk

Mask of Warka

Bull sculpture, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3000 BC

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)