| MITANNI

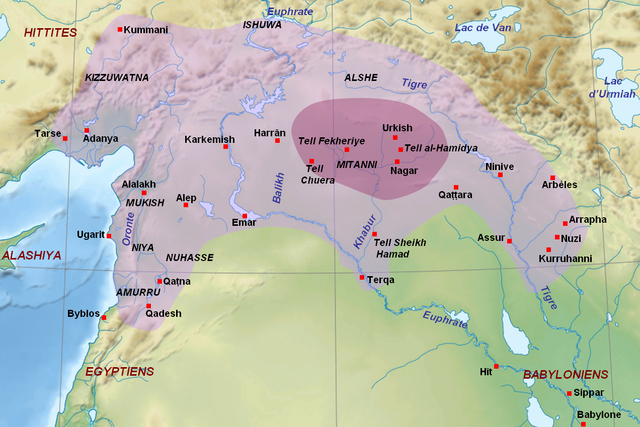

Kingdom of Mitanni at its greatest extent under Parshatatar c. 15th century BC Mitanni (Hittite cuneiform KUR URU Mi-ta-an-ni; Mittani Mi-it-ta-ni), also called Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (Hanikalbat, Khanigalbat, cuneiform Ha-ni-gal-bat, Ha-ni-rab-bat) in Assyrian or Naharin in Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia.

Currently there are two hypotheses regarding how Mitanni was formed :

First theory: Mitanni was already a powerful kingdom at the end of the 17th century or in the first half of the 16th century BC, and its beginnings are from before the time of Thutmose I, so dated to the time of the Hittite sovereigns Hattusili I and Mursili I, when the middle chronology is applied.

Second theory: Mitanni came to be due to a political vacuum in Syria, which had been created first through the destruction of the kingdom of Yamhad by the Hittites and then through the inability of Hatti to maintain control of the region during the period following the death of Mursili I.

If the second hypothesis is considered, Mitanni (c. 1500 to 1300 BC as per short chronology) could have come to be a regional power after the Hittite destruction of Amorite Babylon occurred in 1531 (also in short chronology), and a series of ineffectual Assyrian kings created a power vacuum in Mesopotamia.

While the Mitanni kings and other members of royalty bore names resembling Indo-Aryan phonology, they used the language of the local people, which was at that time a non-Indo-European language, Hurrian. Their sphere of influence is shown in Hurrian place names, personal names and the spread through Syria and the Levant of a distinct pottery type.

The

beginning :

The recent (2017) salvage excavations at the Ilisu Dam in the upper Tigris, southern Turkey, also have shown a very early beginning of Mitanni period, as in the ruins of a temple in Müslümantepe, ritual artefacts and a Mitannian cylinder seal were found, radiocarbon-dated to 1760-1610 BCE. Archaeologist Eyyüp Ay, in his (2021) paper, describes the second phase of the temple as an "administrative center, which had craftsmen working in its workshops as well as farmers, gardeners and shepherds, [that] might have been ruled by a priest bound to a powerful Mitannian leader."

As another recent archaeological excavation suggests, early Mitanni´s territory could have also been to the east of upper Tigris river, as a town now called Bassetki was excavated in northern Iraq, which in all likelihood was the ancient town of Mardama with Mitanni layers from 1550 to 1300 BCE, as its Phase A9 (in trench T2) may alternatively represent a Middle Bronze/Late Bronze transitional, or Proto-Mitanni occupation within 16th century BCE. In a subsequent excavation season, the deeper Phase A10 was identified as having a mix of Middle Bronze and Mitanni potteries, considered to be in the turn of the Middle to the Late Bronze Age transitional period (late 17th - early 16th century BCE).

Archaeologically, Mitanni's first phase in Jazira Region features Late Khabur Ware from around 1600 to 1550 BCE, as this pottery was a continuity from non-Mitannian previous Old Babylonian period. From around 1550 to 1270 BCE, Painted Nuzi Ware (the most characteristic pottery in Mitanni times) developed as a contemporary to Younger Khabur Ware.

At least since around 1550 BCE, in the beginning of Late Bronze age, Painted Nuzi Ware was identified as a characteristic pottery in Mitanni sites, the origin of this decorated pottery is an unsolved question, but a possible previous development as Aegean Kamares Ware has been suggested by Pecorelia (2000), and S. Soldi claims that Tell Brak was one of the first centers specializing in the production of this Painted Nuzi Ware, and analyses on samples support the assumption that it was produced locally in various centers throughout the Mitanni kingdom, it was particularly appreciated in the Jazira Region, but appears only sporadically in western Syrian cities such as Alalakh and Ugarit.

At the beginning of its history, Mitanni's major rival was Egypt under the Thutmosids. However, with the ascent of the Hittite Empire, Mitanni and Egypt struck an alliance to protect their mutual interests from the threat of Hittite domination.

At the height of its power, during the 15th and the first half of 14th century BCE, a large region from North-West Syria to the Eastern Tigris was under Mitanni's control. Mitanni had outposts centred on its capital, Washukanni, whose location has been determined by archaeologists to be on the headwaters of the Khabur River. The Mitanni dynasty ruled over the northern Euphrates-Tigris region between c. 1600 and 1350 BCE. Eventually, Mitanni succumbed to Hittite and later Assyrian attacks and was reduced to the status of a province of the Middle Assyrian Empire between c. 1350 and 1260 BCE.

Geography

:

Name :

The Mitanni kingdom was referred to as the Maryannu, Nahrin or Mitanni by the Egyptians, the Hurri by the Hittites, and the Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat by the Assyrians. The different names seem to have referred to the same kingdom and were used interchangeably, according to Michael C. Astour. Hittite annals mention a people called Hurri (Hu-ur-ri), located in northeastern Syria. A Hittite fragment, probably from the time of Mursili I, mentions a "King of the Hurri." The Assyro-Akkadian version of the text renders "Hurri" as Hanigalbat. Tushratta, who styles himself "king of Mitanni" in his Akkadian Amarna letters, refers to his kingdom as Hanigalbat.

The earliest attestation of the term Hanigalbat can be read in Akkadian within the "Annals of Hattusili I" (c. 1650-1620 BCE) along with the Hittite version mentioning "the Hurrian enemy".

Egyptian sources call Mitanni "nhrn", which is usually pronounced as Naharin(a), from the Assyro-Akkadian word for "river," cf. Aram-Naharaim. The name Mitanni is first found in the "memoirs" of the Syrian wars (c. 1480 BC) of the official astronomer and clockmaker Amenemhet, who returned from the "foreign country called Me-ta-ni" at the time of Thutmose I. The expedition to the Naharina announced by Thutmosis I at the beginning of his reign may have actually taken place during the long previous reign of Amenhotep I. Helck believes that this was the expedition mentioned by Amenhotep II.

The reading of the Assyrian term Hanigalbat has a history of multiple renderings. The first portion has been connected to, Ha-nu," "Hanu" or "Hana," first attested in Mari to describe nomadic inhabitants along the southern shore of the northern Euphrates region, near the vicinity of Terqa and the Khabur River. The term developed into more than just a designation for a people group, but also took on a topographic aspect as well. In the Middle Assyrian period, a phrase "URUKUR Ha-nu AN.TA," "cities of the Upper Hanu" has suggested that there was a distinction between two different Hanu's, likely across each side of the river. This northern side designation spans much of the core territory of Mitanni state.

The two signs that have led to variant readings are "gal" and its alternative form "gal9". The first attempts at decipherment in the late 1800s rendered forms interpreting "gal," meaning "great" in Sumerian, as a logogram for Akkadian "rab" having the same meaning; "?ani-Rabbat" denoting "the Great Hani". J. A. Knudtzon, and E. A. Speiser after him, supported instead the reading of "gal" on the basis of its alternative spelling with "gal9", which has since become the majority view.

There is still a difficulty to explain the suffix "-bat" if the first sign did not end in "b," or the apparent similarity to the Semitic feminine ending "-at," if derived from a Hurrian word. More recently, in 2011, scholar Miguel Valério, then at the New University of Lisbon provided detailed support in favor to the older reading Hani-Rabbat. The re-reading makes argument on basis of frequency, where "gal" not "gal9," is far more numerous; the later being the deviation found in six documents, all from the periphery of the Akkadian sphere of influence. Additionally argued, although graphically distinct, there is a high degree of overlap between the two signs, as "gal9" denotes "dannum" or ""strong"" opposed to "great", easily being used as synonyms. Both signs also represent correlative readings; alternative readings of "gal9" include "rib" and "rip," just like "gal" being read as "rab."

People :

Cylinder seal, c. 16th – 15th century BC, Mitanni The ethnicity of the people of Mitanni is difficult to ascertain. A treatise on the training of chariot horses by Kikkuli, a Mitanni writer, contains a number of Indo-Aryan glosses. Kammenhuber [de] suggested that this vocabulary was derived from the still undivided Indo-Iranian language, but Mayrhofer has shown that specifically Indo-Aryan features are present.

The names of the Mitanni aristocracy frequently are of Indo-Aryan origin, and their deities also show Indo-Aryan roots (Mitra, Varuna, Indra, Nasatya). These Indo Aryan deities are listed in two treaties between Mitanni and Hatti from Hattusa: (treaty KBo I 3) and (treaty KBo I 1 and its duplicates), the kings involved are Sattiwaza of Mitanni and Suppiluliuma the Hittite. The British Museum considers these documents as being from a date around 1350 BC. The common people's language, the Hurrian language, is neither Indo-European nor Semitic. Hurrian is related to Urartian, the language of Urartu, both belonging to the Hurro-Urartian language family. It had been held that nothing more can be deduced from current evidence. A Hurrian passage in the Amarna letters – usually composed in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the day – indicates that the royal family of Mitanni was by then speaking Hurrian as well.

Bearers of names in the Hurrian language are attested in wide areas of Syria and the northern Levant that are clearly outside the area of the political entity known to Assyria as Hanilgalbat. There is no indication that these persons owed allegiance to the political entity of Mitanni; although the German term Auslandshurriter ("Hurrian expatriates") has been used by some authors. In the 14th century BC numerous city-states in northern Syria and Canaan were ruled by persons with Hurrian and some Indo-Aryan names. If this can be taken to mean that the population of these states was Hurrian as well, then it is possible that these entities were a part of a larger polity with a shared Hurrian identity. This is often assumed, but without a critical examination of the sources. Differences in dialect and regionally different pantheons (Hepat/Shawushka, Sharruma/Tilla etc.) point to the existence of several groups of Hurrian speakers.

History

:

Summary :

Cylinder seal and modern impression: nude male, griffins, monkey, lion, goat, c. 15th/14th century BC, Mitanni It is believed that the warring Hurrian tribes and city states became united under one dynasty after the collapse of Babylon due to its sacking by Hittite king Mursili I, and the Kassite invasion. The Hittite conquest of Aleppo (Yamhad), the weak middle Assyrian kings who succeeded Puzur-Ashur III, and the internal strife of the Hittites had created a power vacuum in upper Mesopotamia. This led to the formation of the kingdom of Mitanni.

The first known use (by now) of Indo-Aryan names for Mitanni rulers begins with Shuttarna I who succeeded his father Kirta on the throne. King Barattarna of Mitanni expanded the kingdom west to Aleppo and made the Amorite king Idrimi of Alalakh his vassal, and five generations seems to separate this king (also known as Parattarna) from the rise of Mitanni kingdom. The state of Kizzuwatna in the west also shifted its allegiance to Mitanni, and Assyria in the east had become largely a Mitannian vassal state by the mid-15th century BC. The nation grew stronger during the reign of Shaushtatar, but the Hurrians were keen to keep the Hittites inside the Anatolian highland. Kizzuwatna in the west and Ishuwa in the north were important allies against the hostile Hittites.

After a few successful clashes with the Egyptians over the control of Syria, Mitanni sought peace with them, and an alliance was formed. During the reign of Shuttarna II, in the early 14th century BC, the relationship was very amicable, and he sent his daughter Gilu-Hepa to Egypt for a marriage with Pharaoh Amenhotep III. Mitanni was now at its peak of power.

However, by the reign of Eriba-Adad I (1390–1366 BC) Mitanni influence over Assyria was on the wane. Eriba-Adad I became involved in a dynastic battle between Tushratta and his brother Artatama II and after this his son Shuttarna II, who called himself king of the Hurri while seeking support from the Assyrians. A pro-Hurri/Assyria faction appeared at the royal Mitanni court. Eriba-Adad I had thus loosened Mitanni influence over Assyria, and in turn had now made Assyria an influence over Mitanni affairs. King Ashur-Uballit I (1365–1330 BC) of Assyria attacked Shuttarna and annexed Mitanni territory in the middle of the 14th century BC, making Assyria once more a great power.

At the death of Shuttarna, Mitanni was ravaged by a war of succession. Eventually Tushratta, a son of Shuttarna, ascended the throne, but the kingdom had been weakened considerably and both the Hittite and Assyrian threats increased. At the same time, the diplomatic relationship with Egypt went cold, the Egyptians fearing the growing power of the Hittites and Assyrians. The Hittite king Suppiluliuma I invaded the Mitanni vassal states in northern Syria and replaced them with loyal subjects.

In the capital Washukanni, a new power struggle broke out. The Hittites and the Assyrians supported different pretenders to the throne. Finally a Hittite army conquered the capital Washukanni and installed Shattiwaza, the son of Tushratta, as their vassal king of Mitanni in the late 14th century BC. The kingdom had by now been reduced to the Khabur Valley. The Assyrians had not given up their claim on Mitanni, and in the 13th century BC, Shalmaneser I annexed the kingdom.

The following is a tentative correlation of Mitanni with nearby kingdoms until the reign of Tusratta by Stefano de Martino :

Early

kingdom :

Hurrians are mentioned in the private Nuzi texts, in Ugarit, and the Hittite archives in Hattusa (Bogazköy). Cuneiform texts from Mari mention rulers of city-states in upper Mesopotamia with both Amurru (Amorite) and Hurrian names. Rulers with Hurrian names are also attested for Urshum and Hassum, and tablets from Alalakh (layer VII, from the later part of the Old Babylonian period) mention people with Hurrian names at the mouth of the Orontes. There is no evidence for any invasion from the North-east. Generally, these onomastic sources have been taken as evidence for a Hurrian expansion to the South and the West.

A Hittite fragment, probably from the time of Mursili I, mentions a "King of the Hurrians" (LUGAL ERÍN.MEŠ Hurri). This terminology was last used for King Tushratta of Mitanni, in a letter in the Amarna archives. The normal title of the king was 'King of the Hurri-men' (without the determinative KUR indicating a country).

It is believed that the warring Hurrian tribes and city states became united under one dynasty after the collapse of Babylon due to the Hittite sack by Mursili I and the Kassite invasion. The Hittite conquest of Aleppo (Yamkhad), the weak middle Assyrian kings, and the internal strifes of the Hittites had created a power vacuum in upper Mesopotamia. This led to the formation of the kingdom of Mitanni. The legendary founder of the Mitannian dynasty was a king called Kirta, who was followed by a king Shuttarna. Nothing is known about these early kings.

Barattarna

/ Parsha(ta)tar :

Under the rule of Thutmose III, Egyptian troops crossed the Euphrates and entered the core lands of Mitanni. At Megiddo, he fought an alliance of 330 Mitanni princes and tribal leaders under the ruler of Kadesh. See Battle of Megiddo (15th century BC). Mitanni had sent troops as well. Whether this was done because of existing treaties, or only in reaction to a common threat, remains open to debate. The Egyptian victory opened the way north.

Thutmose III again waged war in Mitanni in the 33rd year of his rule. The Egyptian army crossed the Euphrates at Carchemish and reached a town called Iryn (maybe present day Erin, 20 km northwest of Aleppo.) They sailed down the Euphrates to Emar (Meskene) and then returned home via Mitanni. A hunt for elephants at Lake Nija was important enough to be included in the annals. This was impressive propaganda, but did not lead to any permanent rule. [citation needed] Only the area at the middle Orontes and Phoenicia became part of Egyptian territory.

Victories over Mitanni are recorded from the Egyptian campaigns in Nuhasse (middle part of Syria). Again, this did not lead to permanent territorial gains. Barattarna or his son Shaushtatar controlled the North Mitanni interior up to Nuhasse, and the coastal territories from Kizzuwatna to Alalakh in the kingdom of Mukish at the mouth of the Orontes. Idrimi of Alalakh, returning from Egyptian exile, could only ascend his throne with Barattarna's consent. While he got to rule Mukish and Ama'u, Aleppo remained with Mitanni.

Shaushtatar :

Shaushtatar's royal seal Shaushtatar, king of Mitanni, perhaps the most outstanding Mitannian king, reigned c. 1500–1450 BCE, he sacked the Assyrian capital of Assur some time in the 15th century during the reign of Nur-ili, and took the silver and golden doors of the royal palace to Washukanni. This is known from a later Hittite document, the Suppililiuma-Shattiwaza treaty. After the sack of Assur, Assyria may have paid tribute to Mitanni up to the time of Eriba-Adad I (1390–1366 BC). There is no trace of that in the Assyrian king lists; therefore it is probable that Ashur was ruled by a native Assyrian dynasty owing sporadic allegiance to the house of Shaushtatar. While a sometime vassal of Mitanni, the temple of Sin and Shamash was built in Ashur.

The states of Aleppo in the west, and Nuzi and Arrapha in the east, seem to have been incorporated into Mitanni under Shaushtatar as well. The palace of the crown prince, the governor of Arrapha has been excavated. A letter from Shaushtatar was discovered in the house of Shilwe-Teshup. His seal shows heroes and winged geniuses fighting lions and other animals, as well as a winged sun. This style, with a multitude of figures distributed over the whole of the available space, is taken as typically Hurrian. A second seal, belonging to Shuttarna I, but used by Shaushtatar, found in Alalakh, shows a more traditional Assyro-Akkadian style.

The military superiority of Mitanni was probably based on the use of two-wheeled war-chariots, driven by the 'Marjannu' people. A text on the training of war-horses, written by a certain "Kikkuli the Mitannian" has been found in the archives recovered at Hattusa. More speculative is the attribution of the introduction of the chariot in Mesopotamia to early Mitanni.

During the reign of Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep II, Mitanni seems to have regained influence in the middle Orontes valley that had been conquered by Thutmose III. Amenhotep fought in Syria in 1425 BC, presumably against Mitanni as well, but did not reach the Euphrates.

Artatama

I and Shuttarna II :

When Amenhotep III fell ill, the king of Mitanni sent him a statue of the goddess Shaushka (Ishtar) of Nineveh that was reputed to cure diseases. A more or less permanent border between Egypt and Mitanni seems to have existed near Qatna on the Orontes River; Ugarit was part of Egyptian territory.

The reason Mitanni sought peace with Egypt may have been trouble with the Hittites. A Hittite king called Tudhaliya conducted campaigns against Kizzuwatna, Arzawa, Ishuwa, Aleppo, and maybe against Mitanni itself. Kizzuwatna may have fallen to the Hittites at that time.

Artashumara and Tushratta :

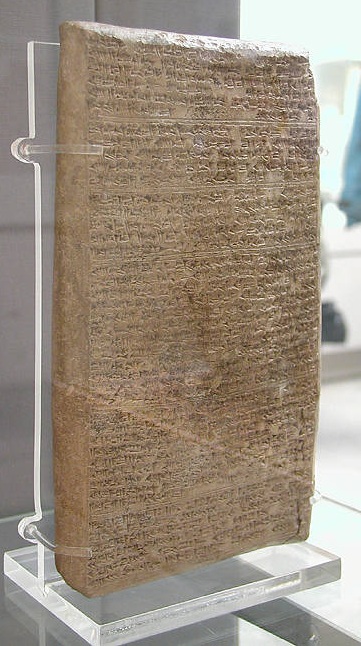

Cuneiform tablet containing a letter from Tushratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep III (of 13 letters of King Tushratta). British Museum Artashumara followed his father Shuttarna II on the throne, but was murdered by a certain UD-hi, or Uthi. It is uncertain what intrigues that followed, but UD-hi then placed Tushratta, another son of Shuttarna, on the throne. Probably, he was quite young at the time and was intended to serve as a figurehead only. However, he managed to dispose of the murderer, possibly with the help of his Egyptian father-in-law, but this is sheer speculation.

The Egyptians may have suspected the mighty days of Mitanni were about to end. In order to protect their Syrian border zone the new Pharaoh Akhenaten instead received envoys from the resurgent powers of the Hittites and Assyria. From the Amarna letters it is known that Tushratta's desperate claim for a gold statue from Akhenaten developed into a major diplomatic crisis.

The unrest weakened the Mitannian control of their vassal states, and Aziru of Amurru seized the opportunity and made a secret deal with the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I. Kizzuwatna, which had seceded from the Hittites, was reconquered by Suppiluliuma. In what has been called his first Syrian campaign, Suppiluliuma then invaded the western Euphrates valley, and conquered the Amurru and Nuhasse in Mitanni.

According to the later Suppiluliuma-Shattiwaza treaty, Suppiluliuma had made a treaty with Artatama II, a rival of Tushratta. Nothing is known of this Artatama's previous life or connection, if any, to the royal family. He is called 'king of the Hurri,' while Tushratta went by the title 'King of Mitanni.' This must have disagreed with Tushratta. Suppiluliuma began to plunder the lands on the west bank of the Euphrates, and annexed Mount Lebanon. Tushratta threatened to raid beyond the Euphrates if even a single lamb or kid was stolen. By the reign of Eriba-Adad I (1390–1366 BC) Mitanni influence over Assyria was on the wane. Eriba-Adad I became involved in a dynastic battle between Tushratta and his brother Artatama II and after this his son Shuttarna III, who called himself king of the Hurri while seeking support from the Assyrians. A pro-Hurri/Assyria faction appeared at the royal Mitanni court. Eriba-Adad I had thus loosened Mitanni influence over Assyria, and in turn had now made Assyria an influence over Mitanni affairs.

Suppiluliuma then recounts how the land of Ishuwa on the upper Euphrates had seceded in the time of his grandfather. Attempts to conquer it had failed. In the time of his father, other cities had rebelled. Suppiluliuma claims to have defeated them, but the survivors had fled to the territory of Ishuwa, that must have been part of Mitanni. A clause to return fugitives is part of many treaties between sovereign states and between rulers and vassal states, so perhaps the harbouring of fugitives by Ishuwa formed the pretext for the Hittite invasion.

A Hittite army crossed the border, entered Ishuwa and returned the fugitives (or deserters or exile governments) to Hittite rule. "I freed the lands that I captured; they dwelt in their places. All the people whom I released rejoined their peoples, and Hatti incorporated their territories."

The Hittite army then marched through various districts towards Washukanni. Suppiluliuma claims to have plundered the area, and to have brought loot, captives, cattle, sheep and horses back to Hatti. He also claims that Tushratta fled, though obviously he failed to capture the capital. While the campaign weakened Mitanni, it did not endanger its existence.

In a second campaign, the Hittites again crossed the Euphrates and subdued Aleppo, Mukish, Niya, Arahati, Apina, and Qatna, as well as some cities whose names have not been preserved. The booty from Arahati included charioteers, who were brought to Hatti together with all their possessions. While it was common practice to incorporate enemy soldiers in the army, this might point to a Hittite attempt to counter the most potent weapon of Mitanni, the war-chariots, by building up or strengthening their own chariot forces.

All in all, Suppiluliuma claims to have conquered the lands "from Mount Lebanon and from the far bank of the Euphrates." But Hittite governors or vassal rulers are mentioned only for some cities and kingdoms. While the Hittites made some territorial gains in western Syria, it seems unlikely that they established a permanent rule east of the Euphrates.

Shattiwaza / Kurtiwaza :

A son of Tushratta conspired with his subjects, and killed his father in order to become king. His brother Shattiwaza was forced to flee. In the unrest that followed, the Assyrians asserted themselves under Ashur-uballit I, and he invaded the country; the pretender Artatama/Atratama II gained ascendancy, followed by his son Shuttarna. Suppiluliuma claims that "the entire land of Mittanni went to ruin, and the land of Assyria and the land of Alshi divided it between them," but this sounds more like wishful thinking. Although Assyria annexed Mitanni territory, the kingdom survived. Shuttarna wisely maintained good relations with Assyria, and returned to it the palace doors of Ashur, that had been taken by Shaushtatar. Such booty formed a powerful political symbol in ancient Mesopotamia.

The fugitive Shattiwaza may have gone to Babylon first, but eventually ended up at the court of the Hittite king, who married him to one of his daughters. The treaty between Suppiluliuma of Hatti and Shattiwaza of Mitanni has been preserved and is one of the main sources on this period. After the conclusion of the Suppiluliuma-Shattiwaza treaty, Piyassili, a son of Suppiluliuma, led a Hittite army into Mitanni. According to Hittite sources, Piyassili and Shattiwaza crossed the Euphrates at Carchemish, then marched against Irridu in Hurrian territory. They sent messengers from the west bank of the Euphrates and seemed to have expected a friendly welcome, but the people were loyal to their new ruler, influenced, as Suppiluliuma claims, by the riches of Tushratta. "Why are you coming? If you are coming for battle, come, but you shall not return to the land of the Great King!" they taunted. Shuttarna had sent men to strengthen the troops and chariots of the district of Irridu, but the Hittite army won the battle, and the people of Irridu sued for peace.

Meanwhile, an Assyrian army "led by a single charioteer" marched on the capital Washukanni. It seems that Shuttarna had sought Assyrian aid in the face of the Hittite threat. Possibly the force sent did not meet his expectations, or he changed his mind. In any case, the Assyrian army was refused entrance, and set instead to besiege the capital. This seems to have turned the mood against Shuttarna; perhaps the majority of the inhabitants of Washukanni decided they were better off with the Hittite Empire than with their former subjects. In any case, a messenger was sent to Piyassili and Shattiwaza at Irridu, who delivered his message in public, at the city gate. Piyassili and Shattiwaza marched on Washukanni, and the cities of Harran and Pakarripa seem to have surrendered to them.

While at Pakarripa, a desolate country where the troops suffered hunger, they received word of an Assyrian advance, but the enemy never materialised. The allies pursued the retreating Assyrian troops to Nilap-ini but could not force a confrontation. The Assyrians seem to have retreated home in the face of the superior force of the Hittites.

Shattiwaza became king of Mitanni, but after Suppililiuma had taken Carchemish and the land west of the Euphrates, that were governed by his son Piyassili, Mitanni was restricted to the Khabur River and Balikh River valleys, and became more and more dependent on their allies in Hattusa. Some scholars speak of a Hittite puppet kingdom, a buffer-state against the powerful Assyria.

Assyria under Ashur-uballit I began to infringe on Mitanni as well. Its vassal state of Nuzi east of the Tigris was conquered and destroyed. According to the Hittitologist Trevor R. Bryce, Mitanni (or Hanigalbat as it was known) was permanently lost to Assyria during the reign of Mursili III of the Hittites, who was defeated by the Assyrians in the process. Its loss was a major blow to Hittite prestige in the ancient world and undermined the young king's authority over his kingdom.

Shattuara

I :

Wasashatta

:

The Assyrians expanded further, and conquered the royal city of Taidu, and took Washukanni, Amasakku, Kahat, Shuru, Nabula, Hurra and Shuduhu as well. They conquered Irridu, destroyed it utterly and sowed salt over it. The wife, sons and daughters of Wasashatta were taken to Ashur, together with much booty and other prisoners. As Wasashatta himself is not mentioned, he must have escaped capture. There are letters of Wasashatta in the Hittite archives. Some scholars think he became ruler of a reduced Mitanni state called Shubria.

While Adad-nirari I conquered the Mitanni heartland between the Balikh and the Khabur from the Hittites, he does not seem to have crossed the Euphrates, and Carchemish remained part of the Hittite kingdom. With his victory over Mitanni, Adad-nirari claimed the title of Great King (sharru rabû) in letters to the Hittite rulers.

Shattuara

II :

Nevertheless, Shalmaneser I won a crushing victory for Assyria over the Hittites and Mitanni. He claims to have slain 14,400 men; the rest were blinded and carried away. His inscriptions mention the conquest of nine fortified temples; 180 Hurrian cities were "turned into rubble mounds," and Shalmaneser "slaughtered like sheep the armies of the Hittites and the Ahlamu his allies." The cities from Taidu to Irridu were captured, as well as all of mount Kashiar to Eluhat and the fortresses of Sudu and Harranu to Carchemish on the Euphrates. Another inscription mentions the construction of a temple to the Assyrian god Adad/Hadad in Kahat, a city of Mitanni that must have been occupied as well.

Hanigalbat

as an Assyrian province :

Mitanni was now ruled by the Assyrian grand-vizier Ili-padâ, a member of the royal family, who took the title of king (sharru) of Hanigalbat. He resided in the newly built Assyrian administrative centre at Tell Sabi Abyad, governed by the Assyrian steward Tammitte. Assyrians maintained not only military and political control, but seem to have dominated trade as well, as no Hurrian or Mitanni names appear in private records of Shalmaneser's time.

Under the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (c. 1243–1207 BC) there were again numerous deportations from Hanigalbat (east Mitanni) to Ashur, probably in connection with the construction of a new palace. As the royal inscriptions mention an invasion of Hanigalbat by a Hittite king, there may have been a new rebellion, or at least native support of a Hittite invasion. The Mitanni towns may have been sacked at this time, as destruction levels have been found in some excavations that cannot be dated with precision, however. Tell Sabi Abyad, seat of the Assyrian government in Mitanni in the times of Shalmaneser, was deserted between 1200 and 1150 BC.

In the time of Ashur-nirari III (c. 1200 BC, the beginning Bronze Age collapse), the Phrygians and others invaded and destroyed the Hittite Empire, already weakened by defeats against Assyria. Some parts of Assyrian-ruled Hanigalbat was temporarily lost to the Phrygians also; however, the Assyrians defeated the Phrygians and regained these colonies. The Hurrians still held Katmuhu and Paphu. In the transitional period to the Early Iron Age, Mitanni was settled by invading Aramaeans.

Indo-Aryan

superstrate :

Another text has babru (babhru, brown), parita (palita, grey), and pinkara (pingala, red). Their chief festival was the celebration of the solstice (vishuva) which was common in most cultures in the ancient world. The Mitanni warriors were called marya, the term for warrior in Sanskrit as well; note mišta-nnu (= mi??ha,~ Sanskrit mi?ha) "payment (for catching a fugitive)."

Sanskritic interpretations of Mitanni royal names render Artashumara (artaššumara) as Arta-smara "who thinks of Arta/?ta," Biridashva (biridaš?a, biriiaš?a) as Pritasva "whose horse is dear," Priyamazda (priiamazda) as Priyamedha "whose wisdom is dear," Citrarata as citraratha "whose chariot is shining," Indaruda/Endaruta as Indrota "helped by Indra," Shativaza (šatti?aza) as Sativaja "winning the race price," Šubandhu as Subandhu "having good relatives," Tushratta (t?išeratta, tušratta, etc.) as *t?aiašaratha "whose chariot is vehement."

Recently, a reference to the word mariannu was found in a letter from Tell Leilan in Northern Syria dating to a period slightly before 1761 BCE, in which date the reign of Zimri-Lim ended in the region of Mari, according to Kroonen et al. this may be considered as an early Indo-Aryan linguistic presence in Syria two centuries prior to the formation of the Mitanni realm, as mariannu can be seen as a Hurrianized form of Indo-Aryan *marya, which means man or youth, associated to military affairs and chariots.

Mitanni rulers :

All dates must be taken with caution since they are worked out only by comparison with the chronology of other ancient Near Eastern nations.

Legacy

:

In 2010, the 3,400-year-old ruins of Kemune, a Bronze Age Mitanni palace on the banks of the Tigris in modern-day Iraqi Kurdistan, were discovered. It became possible to excavate the ruins in 2019 when a drought caused water levels to drop considerably.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |