| ASIANI Tocharians / Yuezhi :

A date of around 3000 BC is used as the probable point at which the core Indo-Europeans began to separate into definite proto languages which were not intelligible to each other. This excepts the Anatolian branch which had already headed southwards from the Pontic-Caspian steppe. The remaining Indo-Europeans (IEs) can be divided into west and east both in linguistic and DNA terms. The western or centum language section would evolve into or subsume Celtic, Italic, Venetic, Illyrian, Ligurian, Vindelician/Liburnian and Raetic branches. The other branches show an eastern or satem heritage which would become the Balts, Indo-Iranians/Indo-Aryans, Sakas, Scythians, and Slavs. The Germanic group shows a mixed heritage. However, early in their expansion, and prior to that of most other Indo-Europeans, one group of centum speakers apparently decided to be different and head eastwards. It is this group which evolved into the Tocharian branch of Indo-Europeans.

It was the increasing realisation that the Tocharians appeared to have a very odd history that confirmed their West Indo-European origins despite their being the most eastern of Indo-Europeans (IEs). Their language showed elements both of eastern and western influences. Were they a West IE tribe (or perhaps a smaller group of West IE warriors) which went eastwards and either assimilated one or more other tribes, or were in heavy contact with them? Quite possibly, but such was the level of admixture in their language that a case could even be made for them being an Anatolian (South IE) language group, or at least being in heavy contact with the Anatolian group. An intriguing possibility was that they were a hybrid people who were made up of various elements of multiple Indo-European groups, scooping up more followers as they passed through West IE, South IE, and East IE groups. The story is too complicated to expand upon here but it is covered in much greater detail in the accompanying feature (see link, right).

More recently, DNA evidence has become key to understanding this complicated story. This has helped to show that the Tocharians were not one group but two (at least!) - and only one of them was truly Tocharian. A closer examination of historical references has helped to support this assertion. The Tocharians migrated far to the east, from the Volga-Ural steppe, across Kazakhstan, to reach the Gorny Altai mountain range (just as did the people of the Afanasevo culture), taking them farther than any other IE groups and so far that that they eventually became known to the early Chinese kingdoms before anyone else recorded their existence. The cause for this extraordinary migration could be put down to pressure by the proto-Indo-Iranians on the Caspian steppe, although the Tocharian migration is conspicuously early.

In those Chinese records, from around the twelfth century BC onwards, they were called the Yueh Chi or Yuezhi. But it is the use of the term 'Yuezhi' which causes confusion in many modern writers, especially many online sources. If the term 'Tocharian' is reserved for the descendants of the original Volga-Ural steppe migration folk then these people - Tocharians - remained in the Altai Mountains area between about 3500-2500 BC in the guise of the Afanasevo culture. Then they were 'encouraged' to drift south to the Tien Shan mountain range by the formation of the local Okunevo culture. From there they soon found the Tarim Basin, and it is here that they largely remained, labelled Yuezhi in Chinese records (the origin of 'Yuezhi' is examined in the Greater Yuezhi section, below).

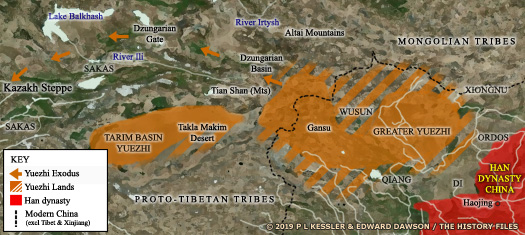

The problems arise in the third century BC, when suddenly there seem to be two divisions of Yuezhi - the Lesser Yuezhi in the Tarim Basin (the Tocharians) and the Greater Yuezhi on the plains of the Gansu region immediately to the east of the Tarim Basin. Many writers take this at face value and assume that the Yuezhi had expanded outwards from the Tarim Basin. However, a closer examination of the Greater Yuezhi and their actions shows that they were satem-speaking IEs with DNA that labelled them as Indo-Iranians, and that their origins almost certainly lay in Central Asia, probably in Bactria or Sogdiana (a fuller explanation of this finding is also shown below, in the Greater Yuezhi section). Expelled from the Gansu plains in the second century BC they began a migration back towards Central Asia where the Tocharian label continued to be applied to them by modern scholars, thanks to confusion over ancient records (see the next paragraph for details). Another layer of confusion can be added by some scholars who have expressed uncertainty about classing these 'Tocharians' as the Greater Yuezhi instead of as close allies, but this is not accepted by the majority of experts.

The name 'Tocharian' (German Tocharisch) was proposed first by F W K Müller in 1907, and a year later by the renowned pair of Tocharianists, Sieg and Siegling. This name is now thought to be a misnomer, but nevertheless remains in use thanks to sheer inertia and the lack of a definitive replacement. Its use came about because the translation of a sacred book used toxrï (Twγry) as an intermediary language. Sieg and Siegling assumed that this intermediary language was identical to the Greek To'kʰaroi and Sanskrit Tukʰāra, denoting the inhabitants of Bactria. As the Sakas became long-established inhabitants of Bactria following the end of Greek rule in the second century BC, the name Tocharisch was proposed for the Saka language. In the end this proved incorrect, but the term stuck for both the centum-speaking IEs of the Tarim Basin and the satem-speaking IEs of Bactria in the second and first centuries BC. It can be seen that 'Tocharian' really should have been used for the Greater Yuezhi inhabitants of Bactria alone, but has instead also been applied to the IEs of the Tarim Basin who are an entirely separate type of IE. Now, for the sake of clarity, 'Tocharian' is being used here for the original Altai migrants and their Tarim Basin descendants (the latter often being termed Lesser Yuezhi in later historical records), while 'Greater Yuezhi' is used here (in green) to distinguish between the two, these being Indo-Iranians who intruded into the Gansu region and were chased out again during the mid-second century BC. The Greater Yuezhi are less important to this page but must be covered in order to clear up any points of confusion between the two groups.

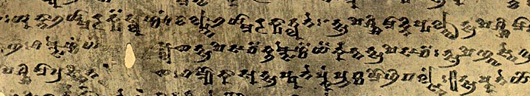

As mentioned, the Tocharian heartland remained the Tarim Basin. The Tocharian languages being used here were first discovered in documents unearthed in expeditions to Chinese Turkestan (East Turkestan, or Xinjiang); the sites are located along what was once the Silk Road. One primary site of Tocharian remains is Turfan, to the north of the Tarim Basin, a depression situated to the north-east of the Takla Makan Desert (Taklamakan). A second major source of Tocharian documents is Kučā, a city to the west of Turfan, in the centre of the northern boundary of the Takla Makan. A third major site, Tumšuq, forms the extreme western boundary of Tocharian finds. This lies along the northern rim of the desert, between Kučā and Kašgʰar, a city at the desert's western extreme.

In linguistic terms, 'Tocharian' in fact denotes two closely related languages, Tocharian A and Tocharian B. Though quite similar, Tocharian A and B are now considered by most scholars to be two distinct languages, and not merely two dialects of one common language. It is still common practice, however, to use the term Tocharian to refer to both languages when no particular distinction needs to be made. Tocharian A is found only in the region of Turfan and Qārāšahr (Karashahr), a nearby oasis located to the west roughly midway between Turfan and Kučā. Tocharian B, by contrast, is found throughout the entirety of this branch of the Silk Road, from Turfan in the east to Tumšuq in the west. Some sources therefore refer to Tocharian A as East Tocharian or Turfanian, since Turfan is at the easternmost extent of the Tocharian sites. Occasionally it is termed Agnean, referring to the Sanskrit designation Agni for Qārāšahr. In this context, Tocharian B is referred to as West Tocharian (though it is found in the east, too) or Kuchean for Kučā. (Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W Anthony, from Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan. Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies, Xinru Liu (Journal of World History 12, 2001), from Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age, BMC Biology (2010 8:15), and from External Links: Peering at the Tocharians through Language, and The United Sites of Indo-Europeans, and Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians, and Linguistics Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, and Indo-European Chronology - Countries and Peoples, and Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (J Pokorny), and the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Tocharian Online: Series Introduction, Todd B Krause & Jonathan Slocum (University of Texas at Austin).)

c.4000 - 3500 BC :

This is the early proto-Indo-European phase in the Indo-European homeland on the Pontic-Caspian steppe. It is during this phase - and probably towards the end of it - that the Tocharian branch begins to break away and migrate eastwards, following the Central Asian steppe towards Mongolia and western China. There they form the Afanasevo culture. The exact details are theoretical but, due to elements of the Tocharian language which preserve early elements of proto-Indo-European, it has been proposed that the Tocharian group is originally made up of western Indo-Europeans who are heavily influenced by their eastern experiences.

c.3500 - 3000 BC :

Other groups of proto-Indo-Europeans have already begun to migrate westwards, away from the Anatolian and Tocharian branches. All of these westwards groups often use four-wheeled wagons to transport their people, and possess wagon/wheel vocabulary that is wholly original to themselves, but which is not shared by the Anatolian group and is only partially shared by the Tocharian group. This demonstrates an arrival of the wheel some time around the point at which the Tocharians are beginning to lose touch with their kinsfolk.

By around 3000 BC the Indo-Europeans had begun their mass migration away from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, with the bulk of them heading westwards towards the heartland of Europe c.3500 - 2500 BC :

A section of the Volga-Ural steppe population decides to migrate eastwards across Kazakhstan, covering a distance of more than two thousand kilometres to reach the Altai Mountains. This incredible trek leads to the appearance of the Afanasevo culture in the western Gorny Altai. These people use four-wheeled wagons to transport their population, all of them speaking a form of proto-Indo-European that is common throughout the Yamnaya horizon.

This culture is intrusive in the Altai Mountains, introducing a suite of domesticated animals, metal types, pottery types, and funeral customs that are derived from the Volga-Ural steppes. This long-distance migration almost certainly separates the dialect group that later develops into the Indo-European languages of the Tocharian branch. The migrants may also be responsible for introducing horse riding to the pedestrian foragers of the northern Kazakh steppes, who are quickly transformed into the horse-riding, wild-horse-hunting Botai culture just at the time at which the Afanasevo migration begins.

c.2350 BC :

The short-lived empire of Lugalannemundu of Adab subjects the Gutians. The latter can only recently have arrived in the Zagros Mountains, possibly the last stage of a migration from the northern coast of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea (if indeed they are Indo-Europeans (IEs)). Linguistically they could be related to the Tocharians, raising the question of how, since the South IEs had split away from other IEs on the steppe even before the Tocharian migration eastwards is theorised to have begun, and certainly before the main migration had taken place in the Volga-Ural steppe event which had founded the Afanasevo culture. c.2000 BC :

Climate change from around this period onwards greatly affects the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), or Oxus Civilisation (centred on the later provinces of Bactria and Margiana), denuding it of water as the rains decline. Eastern Indo-European tribes who have not taken part in the exodus to the west or south have begun the process of becoming the Indo-Iranian branch, and they soon integrate themselves into the BMAC, initially through trade.

In fact, these Indo-Europeans seem to have remained in the old homeland to the north of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea longer than other Indo-European groups, at least partially generating the Sintashta culture and Andronovo horizon to the east. The most easterly group of Indo-Europeans are still the Tocharians, who are later identified as the Yeuh Chi or Lesser Yuezhi in Chinese writings. They remain for the most part nomadic pastoralists throughout the second and first millennia BC, although they have recently migrated from the pasturelands around the Altai Mountains to the Tien Shan mountains range and then onto the Tarim Basin immediately to its south. c.1980 BC :

The archaeological site known as Small River Cemetery No 5 (the 'Xiaohe Tomb Complex'), discovered in 1934 and rediscovered in 2000, lies near a dried-up riverbed in the Tarim Basin. Lying immediately to the south-west of the Altai Mountains, most of the basin is occupied by the Takla Makan Desert (Taklamakan), a wilderness so inhospitable that later travellers along the Silk Road edge along its northern or southern borders. Around 2000 BC the basin is already quite dry thanks to the failing rains which are also affected the BMAC, but the 'Small River People' depend upon the remaining lakes and rivers, as do their descendants until the last of the open water dries up around AD 1600.

Small River Cemetery No 5 consists of a large number of burials, the earliest dating to about 1980 BC, all of which exhibit a distinctive Indo-European appearance The remains, although lying in what is now one of the world's largest deserts, are buried in upside-down boats. Where tombstones may stand, the cemetery instead sports a vigorous forest of poles, interpreted by the archaeologists as male and female sexual symbols, signalling an intense interest in the pleasures or utility of procreation. However, a more prosaic explanation may be that they are quant poles (punting poles) and bladed oars respectively, used to move these river folk along the water bodies which they use to get around. The oldest remains can be dated to this period (give or take forty years) and the two hundred or so desiccated bodies at the site, essentially mummies, have a decidedly European appearance. Their culture appears very similar to that of the recent Afanasevo which had been focussed around the nearby Altai Mountains.

All of the males who are analysed have a Y chromosome that is now mostly found in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Siberia, but rarely in modern China. Mitochondrial DNA, which passes down the female line, consists of two lineages that are common in Europe and one from Siberia. Essentially, the research says, the males generally have an Indo-Iranian heritage. The women also exhibit an Indo-European (IE) background but with the Siberian addition. Since both the Y chromosome and the mitochondrial DNA lineages are ancient, the European and Siberian populations had probably intermarried before entering the Tarim Basin around 2000 BC.

In light of this, the theory still stands that the original Tocharians who were part of the Volga-Ural steppe migration had become dominated by an Indo-Iranian (East IE) group of males (probably a warrior elite). The original Tocharian males would have been sidelined or killed off and further females had been added to the group along the way or at the end of the migration (providing the Siberian admixture). These people, then, are the ancestors of the (Lesser) Yuezhi and Tocharians of later records. Greater

Yuezhi / Lesser Yuezhi (Tocharians / Tokhars) :

It took the Chinese to bring the Tocharians into recorded history, albeit in the guise of the (Lesser) Yuezhi. For at least a millennium - from no later than the twelfth century BC - it seems that these Yuezhi occupied areas of the Tarim Basin, generally as nomadic pastoralists, herding their cattle between various grazing spots according to the season. They also traded with the early Chinese kingdoms, with the Shang collecting large amounts of jade from them. During the Han period, the building of the Great Wall saw a gate placed at the eastern entrance to the Tarim Basin called Yumen Pass, or the Jade Gate, probably in recognition of the source of much of the kingdom's jade. This was also the point at which the Silk Road left China to head west.

The Book of Han mentions the Yuezhi prior to their major migration of the second century BC. Populations continued to occupy the Tarim Basin (avoiding the great eastern-central Takla Makan Desert), and these were commonly known to the Chinese as the Lesser Yuezhi (Tocharians). By the late 200s BC they had also (apparently) spread into the sweeping grasslands closer to the border of the Chinese kingdom, somewhat to the south of the Eastern Steppe, and possibly encompassing at least part of the western section of the Yellow River. These were the Greater Yuezhi, although any relationship to the Tarim Basin Tocharians is now highly doubtful (see below - and note that this group are shown in green text to differentiate them from the Lesser Yuezhi - the Tocharians themselves).

The book states: 'The Great Yuezhi was a nomadic horde [which the Lesser Yuezhi clearly had never been]. They moved about following their cattle, and had the same customs as those of the Xiongnu. As their soldiers numbered more than hundred thousand, they were strong and despised the Xiongnu. In the past, they lived in the region between Dunhuang and Qilian'. Dunhuang is in the northernmost area of the modern Gansu Province to the east of the Tarim Basin, while the Qilian Mountain range borders central Gansu on its western edge. Archaeology is yet to support the claim of Greater Yuezhi occupation around Dunhuag, although steppe nomads are notoriously hard to pin down archaeologically. However, the hostile Xiongnu confederation already occupied at least part of these lands even though, during this period, the Greater Yuezhi were the most powerful nomadic group on the north-western Chinese plains. The Xiongnu ruler, Touman, even sent his eldest son, Modu (Maotun), as a hostage to them which is always a clear sign of dominance by the recipients. The neighbouring Wusun had migrated with the Greater Yuezhi from the Dunhuang/Qilian region and now occupied lands to the north-west of them. They came under frequent Greater Yuezhi attack for their pasture lands and also for slaves. However, these attacks would sow the seeds of the Greater Yuezhi's own fall and exile from these rich lands.

It is during their subsequent period of domination in Bactria from the middle of the first century BC that the Greater Yuezhi are noted as living alongside a people known as the Asioi (Strabo - possibly serving as the origins of the Wusun), Asini (Pliny the Elder), or Asiani (Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus). The '-oi' in Asioi is the Greek suffix, so it should be pronounced 'As', an ancient name which also links to Germanic origins (see feature link, right). Confusingly, the Greater Yuezhi are labelled Tokharoi by ancient writers. Many of these writers were based in Europe, so their sources could be questionable despite their reputations for accuracy, but the original use of 'Tokharian' was to describe a Bactrian people, even though now it is used to describe the Lesser Yuezhi Tocharians of the Tarim Basin (see the main introduction above for a more detailed examination of the reasons for this). The Asioi were said to dominate the Tokharoi, and some modern scholars have equated the Asioi with the Sakas. As the Greater Yuezhi of this period were clearly dominating the Sakas, this claim can be dismissed. The most viable option seems to be that the Asioi provided a ruling division of the Greater Yuezhi.

The problem with the Greater Yuezhi is that there seems to be little reason to tie them in with the Lesser Yuezhi (Tocharians). The former were (later) noted as being satem speakers rather than centum speakers like the Tocharians of the Tarim Basin (East Indo-Europeans and West Indo-Europeans respectively). This is peculiar if they are one and the same people. If there was a switch from one language to the other then it could have been due to the great numbers of other satem-speakers in Bactria, all of which were Indo-Iranian groups, influencing the newer arrivals. However, linguistics experts can see that there is no basis for such a conclusion. The Greater Yuezhi were speakers of Indo-Iranian Bactrian, not former Tocharians who had adopted the language. Tell-tale traces would have been left otherwise. The Lesser Yuezhi (Tocharians) have left written records that prove their centum-speaking credentials (along with hybridised East/West Indo-European DNA results - see the feature link, right). Another argument in favour of there being no ties between the two groups is the fact that, when defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi headed back towards Central Asia, along a path that they knew. They didn't attempt to join (rejoin) the Lesser Yuezhi in the Tarim Basin, because they didn't originate there and had no idea about the Lesser Yuezhi. The Greater Yuezhi were satem-speakers all along, migrating into the Gansu pasturelands from the Kazakh Steppe rather than outwards from the Tarim Basin. Chinese records were wrong in referring to them as Yuezhi at all.

In later years, after the Greater Yuezhi had left the region, a group of Lesser Yuezhi drifted south from their open pasturelands to join the Qiang nomads. Chinese sources also claim the Jie people of the fourth century AD as originating amongst the (non-specific) Yuezhi, but Chinese sources also claim that they were Xiongnu, or Indo-Iranians (like the Greater Yuezhi), or Lesser Yuezhi (Tocharians) of the Tarim Basin. The Jie were largely destroyed by the Wei during a war of AD 350, but again elements appear to have survived the destruction. In addition the small city state of Cumuḍa (alternatively shown as Cimuda or Cunuda, later Kumul, and modern Hami) in Xinjiang is attributed to the Lesser Yuezhi in the first millennium AD.

Various detailed, overly-complicated breakdowns have been provided elsewhere online in order to try and provide an explanation of the name 'Yuezhi or 'Yueh Chi''. The literal translation from Chinese is 'Moon People', which is often dismissed as being meaningless. This may not be the case, though. No one pooh-poohs the Native American use of 'palefaces' to describe Europeans in North America. It is a reasonably direct description of white-faced people by a people who have a naturally darker complexion. The Chinese applied the Yuezhi label both to Tocharians and Indo-Iranians (Lesser Yuezhi and Greater Yuezhi respectively), so it's reasonable to assume that they found the description to be apt. Bearing in mind the fact that the simplest explanation is often the correct one, it seems that the Chinese were talking about people with faces that were the colour of the moon. The Yuezhi literally were Moon People, otherwise known as 'palefaces'.

(Information by Peter Kessler and Edward Dawson, with additional information from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan. Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies, Xinru Liu (Journal of World History 12, 2001), from The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, J P Mallory & Victor H Mair (2000), from The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, René Grousset (1970), and from External Links: Peering at the Tocharians through Language, and The United Sites of Indo-Europeans, and Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians, and Linguistics Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, and Indo-European Chronology - Countries and Peoples, and Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (J Pokorny), and the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Tocharian Online: Series Introduction, Todd B Krause & Jonathan Slocum (University of Texas at Austin), and Silk Road Seattle, Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington.)

c.1270/1190 BC :

Wu-ting is one of the greatest of the Shang dynasty Chinese kings. He enlarges the territory under his control by conducting a war in Guifang which lasts for three years. The Di and Qiang barbarians immediately seek peace terms. Wu-ting subsequently takes Dapeng and Tunwei. At least some of his campaigns are led by his trusted consort, Fuhao (Lady Fu Hao) who, when she predeceases Wu-ting, is buried with a large collection of weapons which includes great battle axes.

Important jade is supplied for the tomb by the Yuezhi (Tocharians), or Niuzhi. They are seemingly reliable trade partners of the Chinese kings, and the export of jade from the Tarim Basin is supported by archaeology from the late second millennium BC onwards, if not earlier. The collection amounts to more than 750 pieces, all from Khotan in the south-western Tarim Basin in modern Xinjiang, showing that the Yuezhi are already settled there, at least within the context of being nomadic pastoralists who still move around their herds of cattle on a seasonal basis. 645 BC :

The Yuezhi (Tocharians) still reside on the border of agricultural China, having been there for longer even than the seemingly ever-present Xiongnu. While the Xiongnu become famous in history for their conflicts with various Chinese kingdoms, the Yuezhi are better known to the Chinese for their role in long-distance trade. The economist of this period in time, Guan Zhong, refers to the Yuezhi, or Niuzhi, as a people who continue to supply jade to the Chinese. 200s BC :

Towards the end of China's 'Warring States' period, by the third century BC, the Xiongnu become a real threat to the north-western Chinese border. By this time the Yuezhi (Tocharians), formerly reliable jade traders to the Chinese, are better known as reliable horse traders. Jade is still included in trade, however.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi 220s BC :

Seemingly within the last century, during China's 'Warring States' period, the Greater Yuezhi have appeared on the sweeping grasslands closer to the border of the Qin kingdom, somewhat to the south of the Eastern Steppe, and possibly encompassing at least part of the western section of the Yellow River. The 'other' Yeuzhi, those who remain in the Tarim Basin and who have acted as jade traders for at least a millennium, are termed the Lesser Yuezhi. It is they who are the descendants of the original Tocharians of the Afanasevo culture.

The hostile Xiongnu already occupied at least part of these lands even though, during this period, the Greater Yuezhi are the most powerful nomadic group on the north-western Chinese plains. The Xiongnu ruler, Touman, has even sent his eldest son, Modu (Maotun), as a hostage to them. The neighbouring Wusun have migrated with the Greater Yuezhi from the Dunhuang/Qilian region and now occupy lands to the north-west of them. The Wusun are clearly occupying secondary status to the Greater Yuezhi, being subject to raids for pasture and slaves.

The Wusun ruler, Nanteou-mi (Nandoumi), is killed during one such Greater Yuezhi raid and his territory is seized. Nanteou-mi's son, Kwen-mo (Kunmo), flees to the Xiongnu to be raised by the Xiongnu ruler. The Xiongnu themselves, perhaps initially taken off guard by the Greater Yuezhi arrival in the region, gradually build up their strength until they are in a position to strike back against their dominant opponents.

210s BC :

Chinese records detail four waves of violence between the Greater Yuezhi and the Xiongnu around this period in time. Generally referred to as wars, they are typical struggles for dominance by competing tribal groups. Now in a position to right some of their perceived wrongs, the Xiongnu launch an unexpected attack on the Greater Yuezhi under the leadership of Touman. While his date of death is 209 BC, it is not clear how long before that event that this attack takes place.

The outcome of the attack is not recorded but it seems to result in little more than some dented pride. The Greater Yuezhi decide to kill their Xiongnu royal hostage, Modu, son Touman, but he escapes on a stolen horse. Perhaps with a score of his own to settle, he soon kills his father and assumes leadership of the Xiongnu.

203 BC :

It takes Modu another seven years before he feels that his warriors are strong enough and numerous enough to launch a fresh attack on the Greater Yuezhi. Having lived with them for an indeterminate period (possibly a year or two, at least) he has a much better idea of what will be needed to defeat them. This attack is a success. A large swathe of Greater Yuezhi territory is seized by the Xiongnu, meaning that they lose the fight and are chased off their pasturelands - possibly without large numbers of their cattle. Suddenly the tables are being turned and the Xiongnu are beginning to assume tribal dominance in the region.

c.176 BC :

The situation has stabilised for approximately a quarter of a century, which suggests that the Greater Yuezhi defeat had not been quite as bad as had been perceived and that the Xiongnu have not felt the need - or do not possess the capability - to follow up on their previous victory. Now, though, for reasons unknown, the Xiongnu launch a fresh attack, either in or shortly before 176 BC. This time the Greater Yuezhi are dealt a crushing defeat when one of Modu's tribal chiefs invades their domains in the Gansu region - the Greater Yuezhi heartland. In a letter which is received by the Han emperor in 174 BC, Modu boasts that, thanks to 'the excellence of his fighting men, and the strength of his horses, he has succeeded in wiping out the Yuezhi, slaughtering or forcing into submission every number of the tribe'. The boast is untrue of course, but the scale of the Greater Yuezhi defeat seems to have been large.

? - c.166 BC :

?

Unnamed 'king of the Yuezhi'. Defeated and killed.

c.166 BC :

Laoshang Chanyu is Modu's son and successor amongst the Xiongnu. In a fresh attack he kills the so-called king of the Greater Yuezhi (if they indeed have only one supreme leader) and, in accordance with nomadic traditions, has 'made a drinking cup out of his skull'. This defeat may only be the latest in a series of more minor encounters over the last decade in which Greater Yuezhi territory is gradually whittled away by the Xiongnu. It is the deciding defeat, though. The Greater Yuezhi begin to desert the north-western plains and the Gansu region.

The

Greater Yuezhi were defeated and forced out of the Gansu region

by the Xiongnu, and their migratory route into Central Asia is pretty

easy to deduct from the fact that they chose to try and settle in

the Ili river valley below Lake Balkhash

Rather than backtrack towards the Tarim Basin though, which would be a natural target if the Greater Yuezhi had originated here, they head to the north of it, seemingly towards the pasture lands of the Dzungarian Basin (in the north of modern Xinjiang), and the passes between the Altai Mountains to the north and the Tian Shan mountain range which provides the northern border to the Tarim Basin. If the Greater Yuezhi are Tocharians then it would seem to be a strange decision to head into the unknown like this - unless the Xiongnu have completely seized the Gansu region, cutting off the Greater Yuezhi from access to their Lesser Yuezhi 'cousins' in the Tarim Basin. If that's the case then the Greater Yuezhi have no other choice left to them. The other option is the one mentioned in the introduction - that the Greater Yuezhi are not related to the Tarim Basin Tocharians and are merely returning back towards Central Asia along the route which brought them to Gansu in the first place.

c.166 - ? BC :

?

Unnamed son of the 'king of the Yuezhi'. Led them into Bactria.

c.165 - 160 BC :

The Greater Yuezhi evacuation of their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom continues, turning from a trickle into a flood. Their westwards migration triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement in Central Asia as they probably follow the route through the Dzungarian Basin and the Dzungarian Gate to penetrate the Kazakh Steppe beyond. This will see them enter the Saka-controlled plains to the north-east of Ferghana.

Along the way the Greater Yuezhi have bumped up against their former neighbours, the Wusun, and a successful attack is launched against them. The westwards migration continues however, possibly with the Wusun still tagging along. By about 160 BC the Yuezhi have encountered the outlying Saka groups on the eastern Kazakh Steppe, primarily in the Ili river valley immediately to the south of Lake Balkhash, which they now occupy. Seemingly, these Saka groups are easily dominated by the Greater Yuezhi, probably due to the sheer weight of numbers on the latter's side, while the Saka are at the eastern edge of their vast swathe of tribal territories which stretch all the way back to the shoreline of the Caspian Sea.

c.150 - 130 BC :

Another defeat is inflicted upon the Greater Yuezhi, this time by an alliance of the Wusun and the Xiongnu. The Wusun chief would appear to be the driving force in this alliance. This probably serves to hurry them along in their westwards migration, pushing them off the Saka plains which they have only just seized. Instead they are forced to enter Transoxiana from the direction of Da Yuan (the Chinese term for Ferghana). They penetrate Sogdiana from its northern reaches, initially dominating the Sakas who are already there.

Soon afterwards they follow the Sakas in invading the former Greek empire region of Bactria (Ta-hia or Ta-Hsia in Chinese records), by around 140 BC. This is where Chinese and western Classical records converge, and allow the Greater Yuezhi to be identified with the migrant arrivals in Bactria who are mistakenly referred to as Tocharians. At about the time of the death of the Indo-Greek King Menander around 130 BC they manage to terminate Greek rule in Bactria. Hellenic cities there appear to survive for some time, as does the well-organised agricultural system. The general area of Bactria soon comes to be called Tokharistan.

The landscape around the walls of the ancient city of Bactra, capital of Bactria (shown here - now known as Balkh in northern Afghanistan, close to the border along the Amu Darya), was and still is very diverse, offering both challenges and rewards to any settlers there, including the newly arrived Tocharians 126 BC :

The Chinese envoy, Chang-kien or Zhang Qian, visits the newly-established Greater Yuezhi capital of Kian-she in Ta-Hsia (otherwise shown as Daxia to the Chinese, and Bactria-Tokharistan to western writers) and the rich and fertile country of the Bukhara region of Sogdiana. His mission is to obtain help for the Chinese emperor against the Xiongnu, but the Greater Yuezhi leader - the son of the dead leader of about 166 BC - refuses the request. Kian-she can reasonably be equated with Lan-shih or Lanshi, but the question of whether this is the Bactrian capital of Bactra (modern Balkh) seems to be much more controversial. It does seem to be likely though, despite scholarly objections.

However, although some modern scholars label the Bactra of this period as the Greater Yuezhi 'capital', Zhang Qian's own contemporary account makes it quite clear that the country is not ruled by a single king who is based in Bactra. Nor does the city contain a central administration. He carefully notes that: 'It [Bactria] has no great ruler but only a number of petty chiefs ruling the various cities'. The Chinese word used to describe the status of Lanshi can refer either to the capital (of a country) or, preferably here, a large town, city, or metropolis. The sense in which it is used clearly edges towards the latter option.

Instead the Greater Yuezhi territory has been divided into five principalities, one for each of the main five tribes (although there is the possibility that one or more may instead be formed of Sakas who had been there before the Yuezhi and have now been absorbed into their ranks). These are the Xiūmì (Hieu-mi), Guishuang (Kuei-shung or Kushan), Shuangmi (Shuang-mi), Xidun (Hi-tun), and Dūmì (Tumi). Although they are independently governed by their own allied prince or xihou, they act together as a confederation. Opinion is divided on whether these divisions exist prior to the Greater Yuezhi settlement in Bactria, with the likelihood being that they are created specifically to administer the new Greater Yuezhi home. It is also during this period that the Greater Yuezhi become literate, quickly progressing to become able administrators, traders, and scholars.

Zhang Qian was a Chinese ambassador and explorer who, between 138-126 BC, met and documented many of the steppe tribes, and visited the Greater Yuezhi capital at Kian-she c.126 - 124 BC :

Having already caused the death of Artabanus' predecessor, Phraates II, the Sakas (partially displaced by the Greater Yuezhi) continue to press Parthian borders for territory. King Artabanus II is killed in one such encounter. The modern writer, René Grousset, instead attributes this act to the Greater Yuezhi who are now settled in Bactria-Tokharistan. The answer could lie in the fact that Saka groups have been dominated by the Greater Yuezhi since the latter's arrival thirty or forty years beforehand, so the Greater Yuezhi could be the driving force behind the fighting against the Parthians while a Saka could still be responsible for the wound which kills Artabanus II. 115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and around Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhar. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies. c.90 - 80 BC :

The Greater Yuezhi continue to drive the Sakas southwards from Central Asia, forcing them further into Indo-Greek territory. One Maues of the Sakas takes control around Gandhar, creating a capital at Taxila in Punjab. He is known in Chinese records as Yinmofu of Jibin, suggesting that the Sakas have been driven from there during the leadership of Maues and that therefore he is already king well before the arrival of the Sakas in Gandhara.

Once there, he issues some coins jointly with a Queen Machene, who may be an Indo-Greek ruler. The Indo-Greek king, Artemidoros (c.90-85 BC), describes himself as 'son of Maues'. Curiously, the contemporary of Artemidoros in Indo-Greek Paropamisadae (western Indo-Greek territory) is Hermaeus Soter. The name is surprisingly close to that of Maues, and Hermaeus holds a level of importance with nomad rulers during and after his reign, with his coins being copied far and wide, especially by the Greater Yuezhi, Sakas, and the emerging Kushans.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards Eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahanas of India c.50? BC :

The Kushan tribe of Greater Yuezhi capture the territory of the Sakas in what will one day become Afghanistan, and have probably already caused the downfall of the Indo-Greek King Hermaeus, conquering Paropamisadae and entering Gandhar in the process. The Kushans now become the most prominent of Greater Yuezhi tribes, gradually uniting all of the tribes into one kingdom and creating a brief but powerful empire by the end of the century. By around AD 100 they have extended their domination to the Tarim Basin and the Tocharian populations there.

The original form of 'kushan' could be 'kuśiññe', meaning 'kuchean' in Tocharian B. Examining more speculatively, could 'kuśiññe' have on the end of it the Celtic and Germanic plural suffix in yet another form, '-iññe'? In British (Belgic?) this is '-aun', in ancient German and common Celtic it is '-on', in modern German it is '-en', and in modern Welsh is it '-ion'.

AD 230 - 250 :

The beginning of the third century AD apparently coincides with the beginning of the Sassanid invasion of north-western India. The Kushans are toppled in former Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria (more recently better known as Tokharistan) and are forced to accept Sassanid suzerainty. There is a split in Kushan rule, so that a separate, eastern section rules independent of the Sassanids, while some of the nobility remain in the west as Sassanid vassals. Even so, Kushan power still gradually wanes in India. 500 - 700s :

The Indo-European languages of the Tocharian branch are still to be found in Xinjiang and the Tarim Basin, in the caravan cities of the Silk Road, but divided at this time into two or three quite distinctive languages, all of which exhibit archaic Indo-European traits.

The surviving Tocharian texts all date to a period roughly between the sixth and eighth centuries AD. The materials are predominantly (but not exclusively) Tocharian A translations of Buddhist texts which are currently in common circulation in Central Asia. Other, secular documents are all written in Tocharian B, leading some scholars to conclude tentatively that Tocharian A, by the time the surviving documents are written, may already be an extinct language, preserved only as the liturgical language - much as Latin will become in Europe.

This example of the Tarim Basin mummies had the usual distinctive European features, along with a full head of red hair which had been braided into pony tails, and items of woven material which match similar Celtic items Immediately to the north, around the Altai Mountains which had provided the anchor for the earliest Tocharian migrations, the Türük people (Göktürks) are vassals of the Rouran khaganate. One theory about their origins suggests that they are Turkified Indo-Europeans, making them Tocharians who had intermarried with proto-Turkic groups in the three-and-a-half millennia since their split from the main body of Indo-Europeans of the Pontic-Caspian steppe. The chances of the Türük people not bearing any relationship to Tocharians seems very slim given their prevalence in the region for the past four thousand years.

Generally, the Indo-European descendants of the Tocharians and Lesser Yuezhi are gradually subsumed within other emerging ethnic identities during the course of the first millennium AD, including the Chinese Jie people, Tibetans (as the Gar or mGar, noted blacksmiths), and the Turkic Uyghurs with their notable Caucasian features who later dominate the region.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |