| CARMANIANS Incorporating the Carmanians, Karmana, & Germanioi :

The ancient province of Carmania lay largely within the modern province of Kerman in central-eastern Iran. Prior to its late sixth century BC domination by the Achaemenid Persians, Carmania seems to have formed part of a much larger and more poorly-defined region known as Ariana, of which the later province of Aria was the heartland. Barely recorded by written history, its precise boundaries are impossible to pin down. It may have encompassed much or all of Transoxiana, the region around the River Oxus (the Amu Darya), and could have reached as far south as the coastline of the Arabian Sea.

Carmania was bordered by the province of Persis to the west (the core territory of the early Parsua), Parthia to the north, Drangiana to the north-east, Gedrosia to the south-east, and the Persian Gulf to the south. The region was also the heartland of the rather mysterious Jiroft culture. This was seemingly a long-lived culture with a vast network of societies which formed some of the world's first cities (see feature link, right). The north of Carmania was (and still is) a poor region, dominated as it is by the Dasht-e Lut, the 'Desert of Emptiness'. The south on the other hand remains a rich and fertile zone that can produce harvests in abundance, as well as containing gold and silver mines along the River Hyctanis or Hytanis.

Much later than the Jiroft culture, Indo-Iranian tribes had been migrating westwards from Transoxiana since the seventeenth century BC or thereabouts, following the collapse of the indigenous Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, or Oxus Civilisation. The early trickle became a flood in the twelfth to tenth centuries BC, and these new arrivals soon created the Median empire and then the Persian empire, both of which incorporated Carmania within their eastern borders. The people who gave this region its new name to replace whatever it had been called by the people of the Jiroft were the Carmanians or Karmana themselves. More probably, in Old Persian this name was something close to the Karmana used to denote the later satrapy. Noted by Herodotus as the Germanioi, they were viewed as an extension of Persis itself and were counted as one of the ten 'clans' (gene) of the Parsua. With the Sagartioi residing in Drangiana, the Karmana here, and the remaining Parsua in Persis, a clear migratory path onto Iran can be discerned.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Zoroastrian Heritage, K E Eduljee, and Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps).)

c.1000 - 900 BC :

The Parsua begin to enter Iran, probably by crossing the Iranian plateau to the north of the great central deserts (through Hyrcania) but also by working round to the south of them. Already separated during their journey, Parsua groups head in two main directions. In time the northern groups find themselves in the Zagros Mountains alongside their cousins, the Mannaeans and Medians. They are attested there during the ninth and eighth centuries but disappear afterwards. The southern groups, perhaps more numerous, trickle in through Drangiana and Carmania, towards southern Iran and begin to settle there.

Located in the Fārs region of Iran, these Parsua come under the overlordship of their once-powerful western neighbour, the kingdom of Elam. In the later stages of Persian settlement, Assyria and Media also claim some control over the region. As Elam's influence weakens, the Persians begin to assert their own authority in the region, although they remain subjugated by more powerful neighbours for quite some time.

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) c.620 BC :

The Medians (possibly) take control of Persia from the weakening Assyrians who themselves had only recently taken control of the region from Elam. According to Herodotus, Media governs all of the tribes of the Iranian steppe. This sudden empire may well include territory to the east which covers Hyrcania, Parthia, Drangiana, and Carmania.

c.546 - 540 BC :

The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea). Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhar, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse.

Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhara, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse.

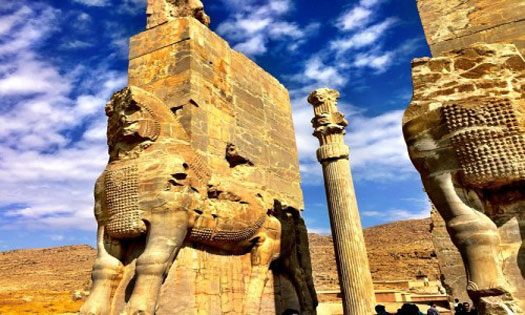

Modern Iran's Makran Coast formed the southern edge of the ancient province of Gedrosia, on what is now the border with south-western Pakistan Persian Satraps of Karmana (Carmania) :

Conquered by Cyrus the Great, the region of Carmania was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was the south-easternmost part of the Median empire. Under the Persians it was formed into a unit of the larger official satrapy or province known as the 'Central Main Satrapy of Pārsa/Persis' which incorporated Persis and Ūja. This is presumed to have comprised the central 'Minor Satrapy of Persis' which lay at the heart of the empire and the 'Minor Satrapy of Karmana'. The latter must have been of inferior rank, since it is not mentioned in the dahyāva lists. Instead its general administration may have been handled from Persis. Carmania's lowly status is confirmed for the time of Alexander the Great, when the post in Carmania represented only a first step in the impressive career of Sibyrtius and was therefore of modest rank.

These eastern regions of the new-found empire were ancestral homelands for the Persians. They formed the Indo-Iranian melting pot from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

The satrapy comprised roughly the area of the modern provinces of Kermān and Lorestān in Iran. The capital is likely to have been on the site of modern Kermān. In Alexander's time, further governors who were presumably of a lower rank are mentioned for the province's southern section - which may correspond to Yutiyā in the Behistun inscription - and for the island of Oaracta / Qešm. In the west the province bordered Persis. Parthawa lay to the north, with Zranka and Gedrosia to the east. The frontier must have been marked by Lake Hāmun and the marshy country of western Sistān (Seistan), and must have run south-south-west from that point to meet the coast near modern Bandar-e Jāsk.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Consumed before the King: The Table of Darius, that of Irdabama and Irtaštuna, and that of his Satrap, Karkiš, Wouter F M Henkelman (via Academia.edu), and from External Links: The Achaemenid Court, Bruno Jacobs & Robert Rollinger (PDF), and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

c.546 - 540 BC : During his campaigns in the east, Cyrus the Great initially takes the northern route from Persis towards Bakhtrish to reassure or subdue the provinces. This route probably involves the 'militaris via' by Rhagai to Parthawa. At some point he takes the more difficult southern route, destroying Capisa along the way (possibly Kapisa on the Koh Daman plain to the north of Kabul - which is possibly also the Kapishakanish named at Behistun as a fortress in Harahuwatish).

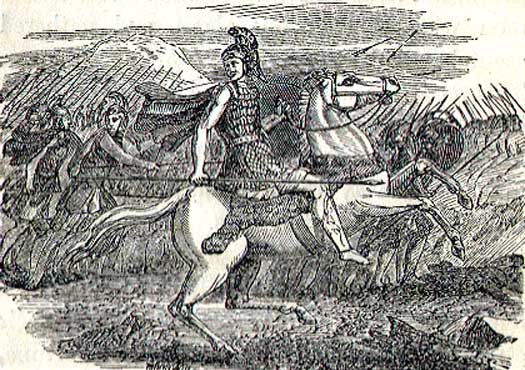

Cyrus the Great freed the Indo-Iranian Parsua people from Median domination to establish a nation that is recognisable to this day, and an empire that provided the basis for the vast territories that were later ruled by Alexander the Great On a fresh leg of the campaign, Cyrus enters the Dasht-i-Lut desert (the modern Dasht-e Loot) on the eastern route out of Karmana towards Harahuwatish. His army faces crippling loses but for the assistance provided by the Ariaspae on the River Helmand. They are named 'the Benefactors' (Greek 'Euergetai') by Cyrus in thanks. This route appears to have been poorly reconnoitred, hinting at a lack of Persian knowledge of this region (and therefore a lack of preceding Median occupation if the existence of its eastern empire is to be believed).

539 - ? BC :

Nabonidus / Nabűna'id / Nabo-Naid : Satrap of Karmana. Former Neo-Babylonian king.

539 BC :

Nabonidus, king of Babylonia, angers his subjects by trying to reintroduce Assyrian culture, including placing the moon god Sin above Babylon's Marduk in terms of importance. Perhaps because of that, resistance to Cyrus the Great of Persia, when he enters Babylonia from the east, is limited to just one major battle, near the confluence of the Diyala and Tigris rivers. On 12/13 October (sources vary), Babylon is occupied by Cyrus. According to the Greek writer, Berossus (author of the Babyloniaka (The Babylonian History), now lost but quoted by later writers), Nabonidus is granted a residency in Karmana (to the east of Persis) as its satrap.

516 - 515 BC :

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gadara and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka. Presumably from there he also passes through neighbouring Carmania, at least in part. Along the way the Sakas are largely defeated and conquered, but probably only along the borders.

The River Oxus - also known over the course of many centuries as the Amu Darya - was used as a demarcation border throughout history and was also a hub of activity in prehistoric times - but during this period it flowed right through the heart of the region that was known as Bactria fl c.490s? BC :

Karkiš / Karkish : Satrap of Karmana & Gedrosia?

c.490s? BC :

Karkiš is mentioned in the Persepolis Fortification Archive or tablets, where he is enjoying a feast with Darius the Great. The date is unknown, so the latter end of Darius' reign has been used here to allow time for Nabonidus to relinquish his own hold over the position as satrap of Karmana. Karkiš is not actually named as satrap, but he is clearly in charge in Karmana. As previously, Karmana is a minor post but now, rather than falling under the administrative eye of Persis, it falls under the authority of Gedrosia, and Karkiš holds both posts. It seems possible that Karmana is separated as a satrapy in its own right by the time of Artaxerxes II (404-359 BC).

360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

? - 329 BC :

Aspastes : Satrap of Karmana. Retained under Greek rule.

334 - 331 BC :

In 334 BC Alexander of Macedon launches his campaign into the Persian empire by crossing the Dardanelles. The first battle is fought on the River Graneikos (Granicus), eighty kilometres to the east. The Persians are defeated, forcing Satrap Arsites of Daskyleion to commit suicide. Sparda surrenders but Karkâ's satrap holds out in the fortress of Halicarnassus with the Persian General Memnon. The fortress is blockaded and Alexander moves on to fight the Lykian mountain folk during the winter when they cannot take refuge in those mountains.

The campaigning season of 333 BC sees Darius III and Alexander miss each other on the plain of Cilicia and instead fight the Battle of Issos on the coast. Darius flees when the battle's outcome hangs in the balance, gifting the Greeks Khilakku and Katpatuka, although pockets of Persian resistance remain in parts of Anatolia. Armina is bypassed during the next move by Alexander, suggesting that it has already capitulated.

Alexander proceeds into Syria during 333-332 BC to receive the submission of Ebir-nari, which also gains him Harran, Judah, and Phoenicia (principally Byblos and Sidon, with Tyre holding out until it can be taken by force). Athura, Gaza, and Egypt also capitulate (not without a struggle in Gaza's case). By 331 BC he is ready for the expected confrontation with Darius III in the heartland of Persian territory, which he also wins. Greek forces sweep eastwards across the empire.

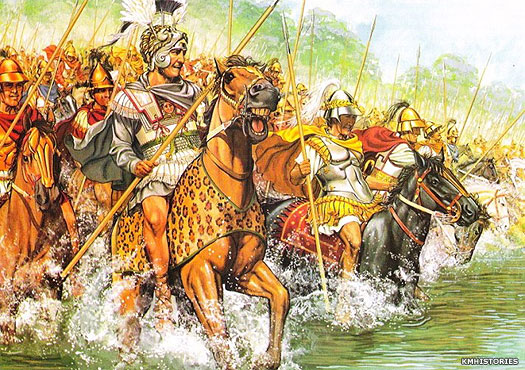

Alexander the Great crossed the River Graneikos (or Granicus) in 334 BC to spark a direct face-off with the Persians that had been brewing for generations, and his victory in battle near the river sent shockwaves through the Persian empire 330 - 328 BC :

In 330 BC distant Sogdiana becomes part of the Greek empire despite the efforts of Bessus, self-styled 'king of Asia', to retain at least some of the Persian territories. His claim is legal, since Bakhtrish is traditionally commanded by the next-in-line to the throne, but Persia has already been lost and his loose collection of eastern allies provides nothing more than a sideshow to the main event - the fall of Achaemenid Persia. Still, it takes Alexander the Great two more years to fully conquer the region.

Argead Dynasty in Carmania :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Carmania was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 305 BC.

Carmania was one of the less important satrapies. Under the Persians it was presumed to have been part of the central main satrapy of Pārsa or Persis which incorporated Persis and Ūja. This was seemingly sub-divided into two minor satrapies which reported to the central satrapy. They consisted of the minor or lesser satrapy of Persis which lay at the heart of the empire and the minor satrapy of Karmana. The latter must have been of inferior rank, since it is not mentioned in the dahyāva lists. This is confirmed for the time of Alexander the Great, when the post in Carmania represented a first step in the impressive career of Sibyrtius and was therefore of modest rank. It was an untroubled posting which was close to the seat of central control and could therefore be given to less practiced satraps.

The satrapy comprised roughly the area of the modern provinces of Kermān and Lorestān in Iran. The capital is likely to have been on the site of modern Kermān (although this city has its direct origins in a town founded by Ardashir I of the later Parthian empire). In Alexander's time, further governors who were presumably of a lower rank are mentioned for the province's southern section - which may correspond to Yutiyā in the Behistun inscription - and for the island of Oaracta / Qešm. In the west the province bordered Persis. Parthia lay to the north, with Drangiana and Gedrosia to the east. The frontier must have been marked by Lake Hāmun and the marshy country of western Sistān (Seistan), and must have run south-south-west from that point to meet the coast near modern Bandar-e Jāsk.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire, Waldemar Heckel (Ed), and from External Links: The Achaemenid Court, Bruno Jacobs & Robert Rollinger (PDF), and Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

330 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

329 - 326 BC :

Aspastes : Persian satrap of Carmania, retained from Karmana. Executed.

326 BC :

Alexander's army enters western India through the passes of the Hindu Kush, and a great battle is fought on the Hydaspes against one of the region's local kings (Porus, of the Northern Indus province). After a further advance eastwards, the troops rebel against the prospect of more battles against another great army, that of Magadh, on the Ganges. Alexander is forced to retreat, abandoning his hopes of conquering India. While he has been away, Aspastes has attempted a rebellion in Carmania. Now he meets Alexander in neighbouring Gedrosia and is promptly executed for his treason.

With Darius II dead and Alexander quickly suppressing his eastern regions, various appointments had to be made so that everyday governance could continue in those regions, with some governors (satraps) being retained, some being executed, and some being replaced by Greeks (Alexander the Great in the Temple of Jerusalem is an oil on canvas by Sebastiano Conca, completed around 1736), while above is the route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns across the ancient world 326 - 325 BC :

Sibyrtius : Satrap of Carmania. Transferred to Arachosia & Gedrosia.

325 BC :

It is reported to Alexander while he is in Carmania that Abisares, king of the mountain domain of the same name in the Northern Indus province, has died, to be succeeded by his son, also known as Abisares. Alexander confirms Abisares in his position, although the Greeks are not particularly well placed to do anything other than this. Their control of the far eastern areas of the Indus has already faded, leaving Abisares largely independent of them. Nothing more is known of him or his kingdom.

324 - 311? BC :

Tlepolemus : Satrap of Carmania. Retained after 311 BC or died?

323 BC :

Upon the death of Alexander his two successors are retained as figureheads while the Greek empire is governed by Alexander's powerful generals. Perdiccas, the leading cavalry commander, is the first general to rule, carrying the title 'Regent of Macedonia', first with Meleager, head of the infantry officers, as his lieutenant, but alone after he has him murdered. In the first of many rounds of reorganisation, Tlepolemus is confirmed as satrap of Carmania.

322 - 320 BC :

The First War of the Diadochi (the successors - the generals of Alexander's army) sees civil war break out between the generals, and Perdiccas is murdered by his own generals during an invasion of Egypt. Philip III agrees terms with the murdering generals and appoints them as regents.

A new agreement with Antipater makes him regent of the Greek empire and commander of the European section. Antigonus remains in charge of Lycia and Pamphylia, to which is added Lycaonia, Syria and Canaan, making him commander of the Asian section. Ptolemy retains Egypt, Lysimachus gains Phrygia and retains Thrace, while the three murderers of the regent Perdiccas - Seleucus, Peithon, and Antigenes - are given the former Persian provinces of Babylonia, Media, and Susiana respectively. Arrhidaeus, the former regent, receives Hellespontine Phrygia, while Tlepolemus is again confirmed in Carmania.

Eumenes of Cardia, Macedonian general and one of Alexander the Great's 'successors' between whom a series of wars were fought 319 - 315 BC :

The death of Antipater leads to the Second War of the Diadochi. He had passed over his son, Cassander, in favour of Polyperchon as his successor (possibly to avoid claims of dynasticism) but the two rivals go to war. Polyperchon allies himself to Eumenes (Alexander's secretary, former satrap of Cappadocia, Mysia, and Paphlagonia), but is driven from Macedonia by Cassander, and flees to Epirus with the infant Alexander IV and his mother Roxana.

Philip III is killed by his stepmother, Olympias, in 317 BC who is herself killed by Cassander the following year. Cassander also captures Alexander IV and Roxana and installs a governor in Athens, subsuming its democratic system. Eumenes is defeated in Asia and is murdered by his own troops, and Seleucus is forced to flee Babylon by Antigonus. The result is that Cassander controls the European territories (including Macedonia), while the Empire of Antigonus controls those in Asia (Asia Minor, centred on Phrygia and extending as far as Susiana). Polyperchon remains in control of part of the Peloponnese. Despite siding with the losing side under Eumenes, Tlepolemus is allowed to remain in Carmania.

314 - 311 BC :

The Third War of the Diadochi results because the Empire of Antigonus has grown too powerful in the eyes of the other generals so Antigonus is attacked by Ptolemy (Egypt), Lysimachus (Phrygia and Thrace), Cassander (Macedonia), and Seleucus (Babylonia). The latter re-secures Babylon itself, plus Carmania, and the others conclude peace terms with Antigonus in 311 BC.

Antigonus continues to fight Seleucus for Babylon but he is defeated in 309 BC and withdraws. At around the same time, Cassander murders the fourteen year-old Alexander IV and his mother, Roxana, ending the Argead line of Macedonians. The fate of Tlepolemus after 315 BC seems to be unknown. Given the fact that he had formerly sided with Eumenes (and therefore Seleucus) it is possible that he is retained, as long as he is still alive, that is.

308 - 301 BC :

The Fourth War of the Diadochi soon breaks out. In 306 BC Antigonus proclaims himself king, so the following year the other generals do the same in their domains. Polyperchon, otherwise quiet in his stronghold in the Peloponnese, dies in 303 BC and Cassander claims his territory. The war ends in the death of Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC.

The Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC ended the drawn-out and destructive Wars of the Diadochi which decided how Alexander's empire would be divided Lysimachus and Seleucus divide Antigonus' Asian territories between them, with Lysimachus receiving western Asia Minor (the Lysimachian empire, including Pergamum and Phrygia), and Seleucus the rest (the Seleucidire, including Susania, Babylonia, Bactria, Carmania, and the Indo-Greek provinces), except Cilicia and Lycia, which go to Cassander's brother, Pleistarchus, and Pontus, which becomes independent, and Phrygia itself, which apparently remains with or is reclaimed by Antigonus' son. Cappadocia is briefly usurped by Amyntas before Seleucus seizes control and permits the restoration of the native ruling dynasty there. Ptolemy remains secure in Hellenic Egypt, Libya, and Palestine.

Macedonian & Parthian Carmania :

The unexpected death of Alexander in 323 BC changed the situation dramatically within his vast Greek empire. Immediately his generals divided the empire between them. Seleucus was able to expand his holdings with some ruthlessness, building up his stock of Alexander's far eastern regions as far as the borders of India and the River Indus (Sindh). Appian's work, The Syrian Wars, provides a detailed list of these regions, which included Arabia, Arachosia, Aria, Armenia, Bactria, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia (as it was known) by 301 BC, Carmania, Cilicia (eventually), Drangiana, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Media, Mesopotamia, Paropamisadae, Parthia, Persia, Sogdiana, and Tapouria (a small satrapy beyond Hyrcania), plus eastern areas of Phrygia.

Once safely under Seleucid control after the conclusion of the Wars of the Diadochi, Carmania was governed by Macedonian satraps, although details about them are woefully lacking. The capital of Seleucus' new empire was initially at Babylon, the heartland of the former Achaemenid empire that had preceded it, but like that empire, this one contained such a mix of peoples and languages that it was rarely a united entity. Gradual losses of territory over subsequent years drove the Seleucid heartland westwards. The capital had to be transferred to Antioch on the Orontes (Syrian Antioch), which was founded around 300 BC and renamed after one of the later Seleucid kings. More territory was hived away by resurgent subject groups or new empires and the Seleucids were eventually bottled up in Syria, with enemies all around them. Meanwhile the eastern provinces, Carmania included, tended to drift into obscurity as western writers lost sight of them. Only occasional glimpses of events there were recorded, and even some of these must be subject to some analysis.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by David Kelleher, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Michael Alram, Touraj Daryaee, & Elizabeth Pendleton (Eds), from The History of al-Tabari, Vol 5, The Sasanids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids and Yemen, Tabari (CE Bosworth (Trans)), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Encyclopćdia Britannica, and Iran on Trip (dead link), and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991) has been followed.)

305 - 303 BC :

Following two years of war on the far eastern border of his empire while he attempts a Greek reconquest of India, Strabo records that Seleucus concedes the Indo-Greek provinces to the ruling Mauryans as part of an alliance agreement. This includes the regions of Paropamisadae (immediately to the east of Bactria, covering northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan), Arachosia (modern southern Afghanistan and northern and central Pakistan, and perhaps extending as far as the Indus), along with northern Indus (Punjab) and probably also southern Indus. Subsequent relations between the Seleucid Greeks and the Mauryans appear to be cordial. Seleucus even appoints Megasthenes as his ambassador to Chandragupta's court.

The Dasht-e Lut salt desert dominates northern Carmania (the modern eastern Iranian province of Kerman), ranking as one of the hottest locations on the planet c.250 - 238 BC :

Areas of eastern Iran and the Seleucid satrapy of Parthia are gradually liberated from Greek rule by tribesmen from the Iranian Plateau. The founder of the dynasty which assumes the leadership of this takeover is Arsaces. His Parthian kingdom is pronounced with the seizure of Asaak (location unknown) in 248/247 BC. By about 238 BC he secures undisputed Parthian independence by attacking and killing the former Macedonian satrap of Parthia, its recently-self-proclaimed king, Andragoras. Hyrcania falls almost immediately afterwards. The Seleucids seem to be able to hold onto the more southerly provinces, such as Carmania and Gedrosia.

219 - 217 BC :

The Fourth Syrian War involves Antiochus fighting the Egyptian Ptolemy IV for control of their mutual border. Troops from Carmania are involved on the Seleucid side. Antiochus recaptures Seleucia Pieria, Tyre, and other important Phoenician cities and their Mediterranean ports, but is fought to a draw at Raphia on Syria's southernmost edge. The subsequent peace treaty sees all the gains other than Seleucia Pieria relinquished.

219 - 217 BC :

Aspasianus the Mede : Satrap of Carmania? Commanded troops during the war.

219 - 217 BC :

Byttacus the Macedonian : Satrap of Carmania? Commanded troops during the war.

209 - 206 BC :

Seleucid ruler Antiochus III invades Parthia. Its capital, Hecatompylos, is occupied and Antiochus forces his way into Hyrcania, with the result that the Parthian king, Arsaces II, is forced to sue for peace. Buoyed by his successes in the east, Antiochus continues on to Bactria. This independent former satrapy is now ruled by Euthydemus Theos after he has deposed the son of the original ruler. Euthydemus is defeated at the Battle of the Arius but resists a two-year siege of the fortified capital, Bactra. In 206 BC Antiochus marches across the Hindu Kush.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi The return journey proceeds through the Iranian provinces of Arachosia, Drangiana, and Carmania. Antiochus arrives in Persis in 205 BC and receives tribute of five hundred talents of silver from the citizens of Gerrha, a mercantile state on the east coast of the Persian Gulf. Having re-established a strong Seleucid presence in the east which includes an array of vassal states, Antiochus now adopts the ancient Achaemenid title of 'great king', which the Greeks copy by referring to him as 'Basileus Megas'.

167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes the former province of Aria from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. It seems possible that Aria (and possibly a rebellious Drangiana too) had already been conquered once by the Arsacids, with the Greco-Bactrians recapturing it, probably under Euthydemus I Theos. During the reign of Eucratides I the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

The other eastern provinces, all of which still appear to be in Seleucid hands, must also fall to the Parthians very quickly after this - including Carmania, Gedrosia, and Margiana - although firm evidence to show a specific date appears to be lacking. Another date which may be valid for these losses is 185 BC, when Seleucus IV loses eastern Iran to Parthian expansion, but the fact that the Parthians fail to expand out of their initial conquests until Mithradates accedes makes this period a more likely one.

The successor to Antimachus I of Bactria was Eucratides I, with this silver tetradrachm being minted in his image at some point during the twenty-six years or so of his reign c.165 BC :

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement.

140 - 130 BC :

Sakas have long been pressing against Bactria's borders. Now, following their long migration from the borders of the Chinese kingdoms, the Greater Yuezhi start to invade Bactria from Sogdiana to the north. Initially, Saka elements who are already in Bactria become vassals to the Greater Yuezhi.

115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC.

Following their own defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhar. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies. Although Carmania doesn't seem to be mentioned directly, its position between Drangiana and Persia would make it likely that this too is still in Parthian hands.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahans of India AD c.210 - 216 :

The fractured Parthian empire is breaking down now. With the claim to rule it already dividing the empire in two on official lines, other minor kingdoms have already started emerging or will soon do so. For the moment they probably acknowledge Parthian overlordship in name, but essentially they are probably all but independent states in their own right. At least three are known - Carmania (ruled by a certain Balash), Margiana (ruled by one Ardashir), and Persis (ruled by one Papak of the Sassanids).

? - 210 :

Balash (Vologeses?) : King of Carmania. Defeated by the Sassanids.

210 :

Having been all but independent for some time, Carmania is currently ruled by one Balash. He is sometimes equated with the Parthian King Vologeses, because Balash or Walash is the New Persian form of Middle Persian Wardakhsh, which is well known in its Greek form as Vologeses. However it is a frequently-used name for Arsacid kings, so there is no guarantee that this is the same Vologeses as the Parthian king.

After subduing two of the five regions of Persis, the Sassanid warlord Ardashir I now conquers Carmania (Kirman) and removes Balash, whose ultimate fate is unknown. Ardashir places one of his own sons in command of the province, another Ardashir, while his own fight against the Parthians continues.

210 - 224? :

Ardashir : Son of Ardashir of the Sassanids. King of Carmania.

224 :

Parthian King Artabanus has left it too late to confront Sassanid expansion within the empire. The Battle of Hormozdgān costs Artabanus his life, leaving the Sassanids as the most powerful faction in Iran. It may be this victory which ends Carmania's brief period as a kingdom and a renewal of its status as a province with Ardashir son of Ardashir I as its first Sassanid governor. Governor Ardashir certainly still holds the post at the start of the reign of Shapur I in AD 241, and Carmania remains a Sassanid province for the duration of the empire (which lasts into the seventh century).

AD 640 - 821 : The region is gradually absorbed into the Islamic empire as it takes Persia. Carmania suffers an invasion in 643 when the marzban (governor) is killed but is apparently regained by the Sassanids for a time. It is used as a bolt-hole for escaping Sassanid nobles in 644 and 650. That last time is barely ahead of a much more significant Muslim invasion which fully conquers Carmania, killing the marzban at Behdesīr (founded by Ardashir I, the modern city of Kerman). At first the city's isolation allowed Kharijites and Zoroastrians to thrive there, but the Kharijites are wiped out in 698, and the population is mostly Muslim by 725 (although a minority group of Zoroastrians survives there to this day).

The modern city of Kerman was founded as Behdesīr by the early Parthian King Ardashir, lying on a sandy plain which is surrounded by mountains to the north and east Muslim governors, or emirs, are appointed to control the Islamic emirate of Khorasan in the name of the caliph. A seemingly partial occupation of Transoxiana by Tang dynasty China is effected in 659, but is ended in 665. The Abbasid caliphate's authority over the region is generally weak, and power eventually passes in the tenth century to the Buwayid dynasty, which maintains control even when the region and city falls to Yamin-ud-Dawlah Mahmud of Ghazna in the early eleventh century. In time, having largely preserved its territorial borders, Carmania becomes the Kerman province of modern Iran.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |