| GEDROSIA Incorporating the Gedrosii, Ichthyophagi, & Oritans :

The ancient province of Gedrosia lay largely within what is now the south-eastern corner of modern Iran, roughly in the lower half of the province of Sistan and Baluchestan, but perhaps also edging across the border into modern Pakistan in South Asia. Prior to its late sixth century BC domination by the Achaemenid Persians, Gedrosia seems to have formed part of a much larger and more poorly-defined region known as Ariana, of which the later province of Aria was the heartland. Barely recorded by written history, its precise boundaries are impossible to pin down. It may have encompassed much or all of Transoxiana - the region around the River Oxus (the Amu Darya) - and could have reached as far south as the coastline of the Arabian Sea.

Following its formation as a province, Gedrosia (or Kedrosia) was bounded to the north by Drangiana, to the east by the Indus region of far western India, to the west by Carmania, and to the south by the Arabian Sea. This region also formed a bridge between the Near East and South Asia. By the first millennium BC it may have been populated largely by Indo-Iranian tribes which had migrated south across the River Oxus and then expanded to the east and west. Those tribes which remained in the regions immediately to the south of the river appear to enter the historical record around the sixth century BC, when they came up against their cousins from the rapidly expanding Persian empire.

The Gedrosii group of Indo-Iranians were based in this region (according to Strabo, while Pliny knew them as the Gedrussi). The Oritans (or Oreitans) had a district of their own in Persian Gedrosia but, seeing as they were seeking a coalition with the Gedrosii, they were probably closely related. As may be guessed, the Gedrosii were neighbours of the Oritans, separated from them by the Tomerus/Hingol. The Ariaspae were also neighbours of the Gedrosii. In the south the province reached the Arabian Sea, where the Ichthyophagi (literally the 'fish-eaters') still practiced a Neolithic forager culture.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Edward Dawson, from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Zoroastrian Heritage, K E Eduljee, and Talessman's Atlas (World History Maps).)

c.620 BC :

The Medians (possibly) take control of Mesopotamia from the weakening Assyrians who themselves had only recently taken control of the region from Elam. According to Herodotus, Media governs all of the tribes of the Iranian steppe. This sudden empire may well include territory to the east which covers Hyrcania, Parthia, Drangiana, and Carmania.

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) c.546 - 540 BC :

The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea).

Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhara, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse.

Persian

Satraps of Gedrosia & Maka :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Gedrosia was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was the easternmost part of the Median empire who themselves had conquered various fellow Indo-Iranian tribes, with the Gedrosii being based in this region (according to Strabo - Pliny knew them as the Gedrussi). Under the Persians, the region was formed into an official satrapy or province.

These eastern regions of the new-found empire were ancestral homelands for the Persians. They formed the Indo-Iranian melting pot from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

When viewing the Persian satrapies, there is a notable decrease of information as one travels from west to east. Gedrosia is not the most poorly-documented of them, though. It is known that the River Kabul formed the border with Harahuwatish. One of the most informative sources when attempting to reconstruct the satrapal administration of Harahuwatish and Gedrosia is that of Alexander's appointments. In northern Arachosia, when he first encountered its large administrative complex, Alexander made important decisions about Zranka, Gedrosia, and Hindush. These regions were therefore subsumed in the Arachosian administrative complex. This may have been the case in Persian times too, although not exclusively, as can be seen from the example set by Karkiš at the start of the fifth century BC.

Maka is presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea which sat on the southern edge of Gedrosia. Maka could instead cover the entire Gedrosia region as the main name in use by the Persians. The region's capital was situated in modern Makrān, while the provincial capital was at Pura. Satraps are known only sporadically. The minor satrapy of the Oritans had a provincial capital named Rhambacia. During the Achaemenid period the region was autonomous (as was that of the Ariaspae), and was probably situated between the Hingol and the Hab. The Hab is selected as a potential eastern boundary because the Oritans followed a wait-and-see policy during Alexander's invasion, reacting only when he moved from Patara in the Indus delta towards them. Paricania also seems to have been a minor satrapy, with Arrian providing the linkage to Gedrosia via the Oritans and Ichthyophagi.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Consumed before the King: The Table of Darius, that of Irdabama and Irtaštuna, and that of his Satrap, Karkiš, Wouter F M Henkelman (via Academia.edu), from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, and from External Links: The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and The Natural History, Pliny the Elder (John Bostock, Ed), and Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Persepolis Fortification Tablets, Richard T Hallock (Oriental Institute Publications at the University of Chicago, available for download as a PDF).)

c.546 - 540 BC :

During his campaigns in the east, Cyrus the Great initially takes the northern route from Persis towards Bakhtrish and Suguda to reassure or subdue the provinces. This route probably involves the 'militaris via' by Rhagai to Parthawa. At some point Cyrus builds a line of seven forts to defend his frontier in Suguda against the tribal Massagetae to the north, the strongest of these being Kyra or Kyreskhata (Cyropolis - the Greek form of its name). Then he takes the more difficult southern route, destroying Capisa along the way (possibly Kapisa on the Koh Daman plain to the north of Kabul - which is possibly also the Kapishakanish named at Behistun as a fortress in Harahuwatish).

Cyrus the Great freed the Indo-Iranian Parsua people from Median domination to establish a nation that is recognisable to this day, and an empire which provided the basis for the vast territories that were later ruled by Alexander the Great 516 - 515 BC :

Achaemenid ruler Darius embarks on a military campaign into the lands east of the empire. He marches through Haraiva and Bakhtrish, and then to Gadara and Taxila. By 515 BC he is conquering lands around the Indus Valley to incorporate into the new satrapy of Hindush before returning via Harahuwatish and Zranka. Along the way the Sakas are largely defeated and conquered, but probably only along the borders.

c.505 BC :

Both Artavazda and Jamāspa are mentioned in the Persepolis Fortification Archive or tablets (forming just about the largest coherent body of material available today on Persian administration). No other mention of them is available, leaving them with nothing more than the most basic details, that Artavazda is satrap of Gedrosia around 505 BC and that Jamāspa is either his predecessor or successor (and perhaps not even immediately - there could be others in between).

fl c.505 BC :

Artavazda : Satrap of Gedrosia.

fl c.500? BC :

Jamāspa : Satrap. Immediate successor or predecessor to Artavazda.

fl c.500s BC :

Megabates : Satrap of Paricania, with Harahuwatish & Gadara.

c.500s BC :

Megabates, son of Megabazus, is father to another Megabazus who in 480 BC is one of the Persian fleet commanders during the campaign against the Greek states. While Herodotus appears not to know where to place Paricania (attributing it to 'Asiatic Ethiopians'), Arrian links it with the Ichthyophagi and Oritans of Gedrosia. It would also seem to be this Megabates who is later satrap of Daskyleion in Anatolia.

The central relief of the North Stairs of the Apadana in Persepolis, now in the Archaeological Museum in Tehran, shows Darius I (the Great) on his royal throne (External Link: Creative Commons Licence 4.0 International) fl c.490s? BC :

Karkiš : Satrap of Karmana & Gedrosia.

c.490s BC :

Karkiš is mentioned in the Persepolis Fortification Archive or tablets, where he is enjoying a feast with Darius the Great. The date is unknown, so the latter end of Darius' reign has been used here to allow time for Nabonidus to relinquish his own hold over the position as satrap of Karmana. Karkiš is not actually named as satrap, but he is clearly in charge in Karmana. As previously, Karmana is a minor post but now, rather than falling under the administrative eye of Persis, it falls under the authority of Gedrosia, and Karkiš holds both posts. It seems possible that Karmana is separated as a satrapy in its own right by the time of Artaxerxes II (404-359 BC).

360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

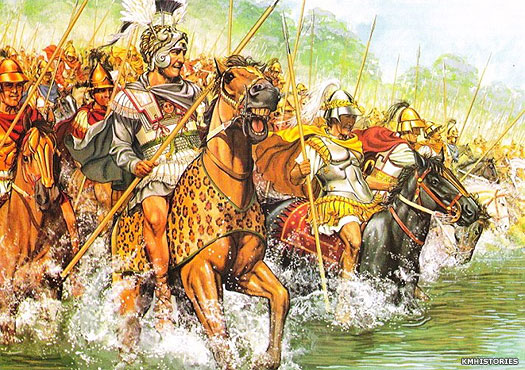

334 - 331 BC :

Alexander of Macedon launches his campaign into the Persian empire by crossing the Dardanelles in 334 BC. The first battle is fought on the River Graneikos (Granicus), eighty kilometres to the east and the Persians are defeated. The campaigning season of 333 BC sees Darius III and Alexander miss each other on the plain of Cilicia and instead fight the Battle of Issos on the coast. Darius flees when the battle's outcome hangs in the balance, gifting the Greeks more territory including Khilakku and Katpatuka.

Alexander proceeds into Syria during 333-332 BC to receive the submission of Ebir-nāri, which also gains him Harran, Judah, and Phoenicia (principally Byblos and Sidon, with Tyre holding out until it can be taken by force). Athura, Gaza, and Egypt also capitulate (not without a struggle in Gaza's case). Now, in 331 BC, he is ready for the expected confrontation with Darius III in the heartland of Persian territory. The Battle of Gaugamela is Darius' final major defeat and he flees eastwards to be murdered by Bessus of Bakhtrish.

Alexander the Great crossed the River Graneikos (or Granicus) in 334 BC to spark a direct face-off with the Persians that had been brewing for generations, and his victory in battle near the river sent shockwaves through the Persian empire 330 - 328 BC :

Gedrosia becomes part of the Greek empire despite the efforts of Bessus, self-styled 'king of Asia', to retain at least some of the Persian territories. His claim is legal, since his satrapy of Bakhtrish is traditionally commanded by the next-in-line to the throne, but Persia has already been lost and his loose collection of eastern allies provides nothing more than a sideshow to the main event - the fall of Achaemenid Persia. Still, it takes Alexander the Great two more years to fully conquer the region, with the work not being completed until 328 BC. Greek-controlled Gedrosia is attached to Arachosia.

Argead Dynasty in Gedrosia :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Gedrosia was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 305 BC.

One of the most informative sources when attempting to reconstruct the satrapal administration of Arachosia and Gedrosia (otherwise shown as Cedrosia or Kedrosia, the 'c', 'k' and 'g' being largely interchangeable in terms of pronunciation) is that of Alexander's appointments. In northern Arachosia, when he first encountered its large administrative complex, Alexander made important decisions about Drangiana, Gedrosia, Northern Indus and Southern Indus. These regions were therefore subsumed in the Arachosian administrative complex. During subsequent years Alexander's many adjustments in this province are not easy to interpret, partly because some of the appointed officers lost their lives during disturbances and through illness. However, the fact that Sibyrtius was satrap of Arachosia and Gedrosia is very good evidence that the two provinces were ruled from Arachosia. The territory of the Ariaspae may also have fallen partially or largely within Gedrosia in the form of a minor satrapy.

The minor satrapy of the Oritans had a provincial capital named Rhambacia. During the Achaemenid period the region was autonomous, but the Oritans followed a wait-and-see policy during Alexander's invasion. They reacted only when he moved from Patara in the Indus delta towards them, and then they sought an alliance with the Gedrosii. Their autonomy probably ended at this point as they were drawn into the satrapy of Gedrosia proper.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Anabasis Alexandri, Arrian of Nicomedia, from Historiae Alexandri Magni, Quintus Curtius Rufus, from Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd, G V Shichkina (Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 1994, 8: 83), from Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire, Waldemar Heckel (Ed), from Alexander the Great, Krzysztof Nawotka (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Bibliotheca Historica, Diodorus Siculus (Perseus Project Texts Loaded under PhiloLogic).)

330 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

333 - 330 BC :

In the winter of 333/332 BC following his capture of Syria, Alexander the Great appoints Menon, son of Cerdimmas, to the satrapy of Coele Syria. He is assigned allied cavalry for the defence of the region while Alexander proceeds into Phoenicia to undertake the sieges of Tyre and Gaza before entering Egypt. Menon's position in Syria is subject to change and, by 331 BC, he is no longer needed there. Instead he is to be found in Zariaspa in Bactria by 329 BC, delivering recruits from Syria to Alexander where he has gained a fresh satrapal command.

The route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns are shown in this map, with them leading him from Europe to Egypt, into Persia, and across the vastness of eastern Iran as far as the Pamir mountain range 330 - 325 BC :

Menon : Satrap of Arachosia (& Gedrosia until 325 BC?). Died 323 BC.

330 - ? BC :

Tiridates? : Minor satrap of Arachosia and/or Gedrosia?

330 - ? BC :

Amedines? : Minor satrap of the Ariaspae?

330 BC :

Arrian reports that the tribes of the Arachoti and Gedrosii are left independent under Alexander. Diodorus states that both receive Alexander with kindness and that the administration of both peoples is given to one Tiridates. Menon becomes the official satrap of Arachosia and Gedrosia (according to Arrian) or of Arachosia alone (according to Curtius), so Tiridates may be a native of the country who handles more direct administrative duties. Amedines is counted as a minor satrap of the Ariaspae, with speculation making him a replacement for Tiridates when he falls out of favour.

326 - 325 BC :

Alexander's army enters western India in 326 BC through the passes of the Hindu Kush, but the troops rebel against the prospect of more battles against another great army, that of Magadha, on the Ganges. Alexander is forced to retreat, abandoning his hopes of conquering India. While he has been away, Aspastes, satrap of Carmania, has attempted a rebellion. Now, returning towards Persis from India, Alexander enters Gedrosia from the east to meet Aspastes who reaches it from the west. The satrap is promptly executed for his treason. Next, a lightning campaign is conducted against the native Oritans who have probably been independent until now. Quickly surrendering, their capital of Rhambaceia (Rhambacia) is converted into a city and may well be renamed Alexandria. Its precise location is yet to be pinpointed.

It is here that the position of satrap in Gedrosia becomes yet more complicated to relate. Menon's death in 323 BC sees his post in Arachosia being filled by the promoted Sibyrtius. Under this satrap, Arachosia and Gedrosia certainly are governed as one joint territory, but Gedrosia apparently gains a satrap of its own in 325 BC - Apollophanes - with Leonnatus as commander of the satrapy's garrison. Tiridates seems not to be mentioned, lending support to the theory that he is a native minor satrap.

Modern Iran's Makran Coast formed the southern edge of the ancient province of Gedrosia, on what is now the border with south-western Pakistan 325 BC :

Apollophanes : Greek satrap of Gedrosia. Killed.

325 BC :

Following the departure of Alexander and the main army, the Oritans almost immediately rebel. Apollophanes is killed but Leonnatus is able to quell the rebellion. Leonnatus then apparently rejoins the main army while one Thoas is appointed as the replacement for the slain Apollophanes. The death of Thoas in 323 BC is from natural causes but this may be the point at which Gedrosia's administration is handed to Arachosia.

325 - 323 BC :

Thoas : Greek satrap of Gedrosia. Died.

323 - 303 BC :

Sibyrtius : Greek satrap of Arachosia & Gedrosia. (Formerly in Carmania.)

315 - 312 BC :

Eumenes is defeated in Asia and is murdered by his own troops, and Seleucus is forced to flee Babylon by Antigonus. The result is that Cassander controls the European territories (including Macedonia), while the Antigonids control those in Asia (Asia Minor, centred on Lycia and extending as far as Susiana), and also temporarily some of the eastern territories, including Aria, Drangiana, and Parthia, where Stasander is removed from office and replaced by Euitus.

312 - 306 BC :

The Wars of the Diadochi decide how Alexander the Great's empire is carved up between his generals, but the period is very confused, especially in the east. Bactria is taken by the Seleucids around 312 BC. With that being the senior region of the eastern territories it is likely that most of the others fall into line even if they are not directly visited by Seleucus, so that by 301 BC he controls the entire east of the former empire.

Macedonian & Parthian Gedrosia :

The unexpected death of Alexander in 323 BC changed the situation dramatically within his vast empire. Immediately his generals divided the empire between them. During the subsequent war, Seleucus was able to expand his holdings with some ruthlessness, building up his stock of Alexander's far eastern regions as far as the borders of India and the River Indus (Sindh). Appian's work, The Syrian Wars, provides a detailed list of these regions, which included Arabia, Arachosia, Aria, Armenia, Bactria, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia (as it was known) by 301 BC, Carmania, Cilicia (eventually), Drangiana, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Media, Mesopotamia, Paropamisadae, Parthia, Persis, Sogdiana, and Tapouria (a small satrapy beyond Hyrcania), plus eastern areas of Phrygia.

Once safely under Seleucid control after the conclusion of the Wars of the Diadochi, Gedrosia was governed by Macedonian satraps, although details about them are woefully lacking. The capital of Seleucus' new empire was initially at Babylon, the heartland of the former Achaemenid empire that had preceded it. Like that empire, this one contained such a mix of peoples and languages that it was rarely a united entity. Gradual losses of territory over subsequent years drove the Seleucid heartland westwards. The capital had to be transferred to Antioch on the Orontes (Syrian Antioch), which was founded around 300 BC and then renamed after one of the later Seleucid kings. More territory was hived away by resurgent subject groups or new empires and the Seleucids were eventually bottled up in Syria, with enemies all around them. Meanwhile the eastern provinces, Gedrosia included, tended to drift into obscurity as western writers lost sight of them. Only occasional glimpses of events there were recorded, and even some of these must be subject to some analysis. Where information conflicts regarding the Indo-Greek territories, Osmund Bopearachchi's work has been followed.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by David Kelleher, from Osmund Bopearachchi's Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (1991), from Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Books 11-12, Volume 1, Marcus Junianus Justinus, John Yardley, & Waldemar Heckel, from The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Michael Alram, Touraj Daryaee, & Elizabeth Pendleton (Eds), from The History of al-Tabari, Vol 5, The Sasanids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids and Yemen, Tabari (CE Bosworth (Trans)), and from External Links: the Ancient History Encyclopaedia (dead link), and Encyclopćdia Britannica, and Iran on Trip (dead link), and Appian's History of Rome: The Syrian Wars at Livius.org.)

305 - 303 BC :

Despite the near constant vying for territory against the other generals in the west, Seleucus Nicator is still able to pay attention to his easternmost borders. He engages in two years of warfare here in an attempt to stage a Greek reconquest of Alexander's territories on the edge of India, but eventually without success. Strabo records that Seleucus concedes the Northern Indus provinces to the ruling Mauryans as part of an alliance agreement.

The Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC ended the drawn-out and destructive Wars of the Diadochi which decided how Alexander's empire would be divided This concession includes the regions of Paropamisadae (immediately to the south and east of Bactria, covering northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan), Arachosia (modern southern Afghanistan and northern and central Pakistan, and perhaps extending as far as the Indus), along with Northern Indus (Punjab) and probably also Southern Indus. Subsequent relations between the Seleucid Greeks and the Mauryans appear to be cordial. Seleucus even appoints Megasthenes as his ambassador to Chandragupta's court.

c.250 - 238 BC :

Areas of eastern Iran and the Seleucid satrapy of Parthia are gradually liberated from Greek rule by tribesmen from the Iranian Plateau. The founder of the dynasty which assumes the leadership of this takeover is Arsaces. His Parthian kingdom is pronounced with the seizure of Asaak (location unknown) in 248/247 BC.

By about 238 BC he secures undisputed Parthian independence by attacking and killing the former Macedonian satrap of Parthia, its recently-self-proclaimed king, Andragoras. Hyrcania falls almost immediately afterwards. The Seleucids seem to be able to hold onto the more southerly provinces, such as Carmania and Gedrosia.

206 - 205 BC :

Seleucid ruler Antiochus III returns from his expedition into the eastern regions by passing through the provinces of Arachosia, Drangiana, and Carmania. He arrives in Persis in 205 BC and receives tribute of five hundred talents of silver from the citizens of Gerrha, a mercantile state on the east coast of the Persian Gulf. Having re-established a strong Seleucid presence in the east which includes an array of vassal states, Antiochus now adopts the ancient Achaemenid title of 'great king', which the Greeks copy by referring to him as 'Basileus Megas'.

The kingdom of Bactria (shown in white) was at the height of its power around 200-180 BC, with fresh conquests being made in the south-east, encroaching into India just as the Mauryan empire was on the verge of collapse, while around the northern and eastern borders dwelt various tribes that would eventually contribute to the downfall of the Greeks - the Sakas and Greater Yuezhi 167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes the former province of Aria from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. It seems possible that Aria (and possibly a rebellious Drangiana too) had already been conquered once by the Arsacids, with the Greco-Bactrians recapturing it, probably under Euthydemus I Theos. During the reign of Eucratides I the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

The other eastern provinces, all of which still appear to be in Seleucid hands, must also fall to the Parthians very quickly after this - including Carmania, Gedrosia, and Margiana - although firm evidence to show a specific date appears to be lacking. Another date which may be valid for these losses is 185 BC, when Seleucus IV loses eastern Iran to Parthian expansion, but the fact that the Parthians fail to expand out of their initial conquests until Mithradates accedes makes this period a more likely one.

c.165 BC :

Defeated by the Xiongnu, the Greater Yuezhi are forced to evacuate their lands on the borders of the Chinese kingdom. They begin a migration westwards that triggers a slow domino effect of barbarian movement.

Zhang Qian was a Chinese ambassador and explorer who, between 138-126 BC, met and documented many of the steppe tribes, and visited the eventual Greater Yuezhi capital at Kian-she 140 - 130 BC :

Sakas have long been pressing against Bactria's borders. Now, following a long migration from the borders of the Chinese kingdoms, the Greater Yuezhi start to invade Bactria from Sogdiana to the north. Initially, Saka elements who are already in Bactria become vassals to the Greater Yuezhi. At around the time of the death of the Indo-Greek King Menander in 130 BC, the Greater Yuezhi overrun Bactria and end Greek rule. Heliocles may possibly invade the western part of the Indo-Greek kingdom, as there are strong suggestions that the Eucratids continue to rule there, especially in the form of Heliocles' presumed son, Lysias.

115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhara. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahanas of India c.AD 4 - 20 :

It is from this point that the Parthian empire, weakened by successive civil wars and squabbling over the throne, gradually begins to fade, breaking up into smaller kingdoms which remain loosely united for two hundred years. Having assumed power and seen to the removal of Phraates, Queen Musa is now replaced on the throne by her step-son, Orodes. Within just a couple of years he too is despised by the nobility and is assassinated.

The nobility ask Rome to return one of their hostage princes, but they also despise Vonones when he arrives for being a 'slave' (their term for those held as hostages). Only the accession of Artabanus III around AD 10 restores any sense of stability to the empire... but then he loses Gedrosia to a vassal who founds a dynasty known as the Pahlavas.

Indo-Parthians / Pahlavas / Suren Kingdom :

The Kushans had emerged as a powerful component of the Greater Yuezhi confederation, sweeping to dominance over large areas of southern Central Asia and neighbouring South Asia. Their power towards the west was checked by the Indo-Parthians, or Pahlavas. Of an Indo-Iranian ancestry which they shared with the Kushans, the Indo-Parthians had their origins in territory within modern Iran. The first Indo-Parthian monarch, Gondophares, was a vassal of the Parthian Arsacids, governing territory of theirs deep into the southern fringes of Central Asia. With the empire fragmenting over the course of several decades, he declared his independence from it and ventured eastwards to establish his own kingdom in present day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India, sharing a degree of their domination of the region with the Indo-Scythians, who still remained seemingly independent in their Kshaharata strongholds around Gujarat. The arrival of the Indo-Parthians seems to have taken the prize of Kashmir from Indo-Scythian hands though.

Information, and especially dating, for the Indo-Parthians is hard to come by, some of it being provided by numismatic evidence only. For that reason alone the dating used here is often approximate and uncertain. The prime capital during the height of the kingdom was Taxila (now in Pakistan), former capital of the Persian satrapy or province of Thatagush, although generally it seems to have formed part of the much larger satrapy of Gadara. The nearby Jandial temple complex is thought to be a Zoroastrian fire temple of the Indo-Parthian period. During the kingdom's decline, Kabul (of the satrapy of Paropamisus) or Purushpura (present day Peshawar in Pakistan) seem to have been favoured.

Although there seems to be no other evidence to back it up, Gondophares has been linked to the House of Suren within the Parthian empire (by Ernst Herzfeld). This was an important noble house whose members were often responsible for crowning the Arsacid king. No more than two generations prior to Gondophares, a Parthian cavalry commander by the name of Surena of the same house had been responsible for inflicting a catastrophic defeat upon the Romans at the Battle of Carrhae, so it was certainly a name to be reckoned with. It would seem to be this potential family link which is responsible for some map-makers showing the Indo-Parthian territories under the label 'Suren Kingdom'.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information by Abhijit Rajadhyaksha, from Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c.326 BC to c.300 AD), Satyendra Nath Naskar, from Das Haus Sūrēn von Sakastan, Ernst Emil Herzfeld (Ed, Archćologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, I, Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1929), from The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, John M Rosenfield (University of California Press, 1967), from Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Christianity, Suresh K Sharma & Usha Sharma (Eds), from The Final Nail in the Coffin of Azes II, Robert Senior (Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society No 197, 2008), from Indo-Scythian Coins and History IV, Robert Senior (CNG, 2006), from Life of Apollonius Tyana, Philostratus, from On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kushana World, Doris Srinivasan (BRILL, 2007), and from External Link: Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

c.AD 10 :

The Indo-Greek kingdom disappears under Indo-Scythian pressure. It seems to be Rajuvula, the Saka kshatrapa of Mathura, who invades what is virtually the last free Indo-Greek territory in the eastern Punjab, and kills the Greek ruler, Strato II and his son. Pockets of Greek population probably remain for some centuries under the subsequent rule of the Kushans and Indo-Parthians. By now the Indo-Parthians under Gondophares already seem to have captured Kashmir from the Indo-Scythians, relieving them of an important prize.

c.AD 20 - 50 :

Gondophares (I) : Parthian vassal who declared independence.

c.20 :

With the Parthian empire gradually fracturing and collapsing, Gondophares ventures east into recently-captured territory where he establishes an independent Indo-Parthian kingdom in what is now Afghanistan. His kingdom stretches from Arachosia and Gedrosia to northern India, perhaps also with territory within Drangiana. Despite various efforts, Parthian King Artabanus is unable to restore these Indo-Parthians to Parthian control. Gondophares does not rule a single unitary kingdom, however. His authority involves the cooperation of a number of lesser figures, many of whom had been regional satraps under Parthian or Saka control. This seem to include the Apracarajas of the Bajaur area, the aforementioned 'Great Satrap' of Saka-controlled Mathura, Rajavula (floruit c.AD10), and Zeionises, Saka satrap of Kashmir and Chuksa in north-western India (floruit c.10 BC-AD 10).

This photo illustrates both sides of a coin issued by Gondophares showing the Greek goddess Nike, and legends in both Greek and Kharoshthi, clearly demonstrating the powerful influence of Greek culture in the region even after the collapse of the last Greek kingdom Shortly afterwards, Kujula Kadphises founds the Kushan empire in Bactria-Tokharistan and seizes a long corridor of territory which stretches to the middle Amu Darya. This has the deliberate effect of creating a barrier around Sogdiana, which is then isolated for almost three hundred years. It would seem to be during this period that Gondophares briefly holds power over a great many of the diminished Sakas, also counting Kshatrapa Sodasa of Mathura as a vassal (a successor of Rajavula).

c.30 - 50? :

A somewhat remarkable story which is usually ascribed to the reign of Gondophares I is a visit to the kingdom by the Judean St Thomas the Apostle. He would seem to use established trade routes to reach India, although it would have to be north-western India for his interaction with Gondophares. He is recruited as a carpenter to serve at the court of the king who is named as 'Gudnaphar' in surviving texts.

Chapters 2 and 3 of The Acts of Thomas show him embarking on a sea voyage to India, while Chapter 17 describes his time in India. He establishes many converts to Christianity, including members of royal families, passes into a neighbouring kingdom, suffers martyrdom there (at the hands of an unidentified King Mazdai), and is buried there. His remains are later transferred to Edessa in Mesopotamia where they are venerated.

c.30 - 80 :

The Kushan ruler, Kadphises, subdues the Sakas and establishes his kingdom in Bactria and the valley of the River Oxus (the Amu Darya). This means defeating the Indo-Parthians and successfully recapturing the main areas of their kingdom, which include Gandhara. The Indo-Parthians survive in northern India and Pakistan, mainly Sakastan (former Saka territory) and Arachosia, with perhaps tendrils of territory reaching into Gedrosia and even Gandhara where a Greek-speaking Indo-Greek king of Taxila named Phraotes is met by the Greek philosopher, Apollonius of Tyana, somewhere close to AD 46.

This photo illustrates a Kadphises I coin which was discovered in the Bactria-Tokharistan region and which has on it a corrupt Greek legend c.50 - 65 :

Abdagases I : Nephew. Possibly retained much of his uncle's territory.

c.AD 50 - 65 :

Sanabares starts out as the Parthian satrap of Margiana and, being an eastern Parthian, is sometimes included as one of the rebellious Indo-Parthian rulers despite being located well north and west of the main Indo-Parthian territories.

At some point he rebels against the weak Parthian king during a period in which the throne is witnessing a constant succession of incumbents and anyone who is a member of the Arsacid family may mount their own claim if they have enough backing. At his satrapal capital of Merv, Sanabares starts minting his own coins around AD 50, with these coins being the only clear indication of his rebellion in terms of historical sources. It takes until AD 65 before the latest Parthian king in the west, Vologeses I, can restore central authority in Margiana, at least to an extent.

fl c.60 :

Satavastres : Co-ruler or dominant in one region only?

fl c.70 :

Sarpedones / Gondophares II : Adopted the name Gondophares. Ruled for only a short time?

c.70 :

Sarpedones succeeds as ruler of the kingdom and adopts the name Gondophares. His rule is not nearly so certain as that of his more illustrious predecessor, however. He may not even be the sole ruler, with Abdagases perhaps still ruling areas towards the west. Issues of his coinage are somewhat fragmented, appearing in Arachosia, eastern Punjab (a region which could be included in the former satrapy of Northern Indus), and Sindh, all towards the south and east of the Indo-Parthian territories.

Shown here are both sides of a coin issued during the rule of Sarpedones (Gondophares II), with him diademed and draped on the left and the goddess Nike standing on the right fl c.70 :

Orthagnes / Orthagnes-Gadana : Also known as Gondophares III Gadana.

c.70 - c.77? :

Orthagnes, who renames himself Gondophares III Gadana, may also rule only parts of the kingdom, with Abdagases now dominant towards the east. However, his coins also appear in Arachosia and eastern Punjab, just like those of Sarpedones, suggesting that he succeeds Sarpedones. In turn he is succeeded by his son while Abdagases is succeeded by Sases.

fl c.77 :

Ubouzanes : Son. Known from numismatic evidence only

fl c.85 :

Sases / Gondophares IV Sases : Nephew of Aspavarma of the Apracarajas.

c.85 :

Sases would appear to succeed Abdagases in many of the latter's territories. He is opposed by (or at least is contemporary with) Orthagnes and his son, Ubouzanes, for an unknown period of time, but Sases himself is claimed by Robert Senior as reigning for at least twenty-six years, perhaps around AD 65-91 or later.

fl c.90 :

Abdagases II : Same as Agata of Sindh? Outlasted Pacores?

c.90 - 100 :

Abdagases is another relatively insignificant Indo-Parthian ruler, with very little numismatic evidence to point to anything other than a brief reign of little consequence. A coin found in Sindh names one Agata, possibly a corruption of his name or possibly another minor rival. The Indo-Parthians are rapidly declining now, as can be seen around AD 100 when the neighbouring Kushans capture former Indo-Greek Arachosia from them.

This photo illustrates a Kushan coin of Kadphises I which was discovered in the Bactria-Tokharistan region when the Kushan took control from the declining Indo-Parthians c.100 - 135 :

Pacores / Pakores : Only in Drangiana & Gandhara.

Blessed with a full Greek education and able to speak Greek fluently (showing a continuation of strong Greek influence in the region), Pacores is the last king with any real power. However, even that does not extend into former core Indo-Parthian territories in Arachosia and Sindh.

One or more more Indo-Parthian kings follow him but in diminished circumstances, and virtually unknown to history - possibly Abdagases II also outlasts him but he continues to stamp his coins with his name while the other or others do not. (Pacores' reign has been pushed back into the first century AD by Robert Senior in his own dating series which is largely based on numismatic evidence.)

c.135 : ? : Known from numismatic evidence only.

c.140? :

By this date, if not before, the last Indo-Parthians are conquered by the Kushans, even the minor, unnamed Indo-Parthian kings. Indo-Parthians also remain in some of the areas that they have conquered in the past. Around this time, Rudradaman I of the Western Kshatrapas divides his empire into provinces so that they are easier to administer. The Girnar records show that an Indo-Parthian amatya (governor) by the name of Suvisakha is placed in charge of the administration of Ananta-Surastra. In the third century the Kushans are in turn largely conquered by the Sassanids, essentially restoring Gedrosia to a form of Persian empire control.

Typical Indo-Scythians in India, still the notable horse-borne warriors of their Indo-European heritage but by now greatly imbued with Indian cultural influences Today, Gedrosia is better known as Baluchistan, after a people who seem to have arrived in the tenth century AD following the Islamic invasion of the region. There is the chance that 'Baluchistan' is based on the Indo-Iranian name 'badlaut', a development of a possible Persian name, 'uadravati', which in theory could be the origin of the Greek 'Gedrosia'. The theory remains somewhat contentious though. Modern Baluchistan is divided, with about one third of it in Iran, and the rest, the eastern sections, forming a large part of southern Pakistan.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |