| MARGIANA / MERGU Margiana

/ Mergu :

A Bronze Age culture emerged in Central Asia around 2200-1700 BC, at the same time as city states were beginning to flourish in Anatolia. It was known as the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex, or Oxus civilisation, and Indo-European tribes soon integrated into it. Probably these very same people were very shortly to be found entering India, and those who remained behind appear to enter the historical record in around the sixth century BC, when they came up against the rapidly expanding Persian empire.

The ancient province of Margiana lay largely within what is now central and western Turkmenistan. The Kopet Dag Mountains which today form a frontier with Iran were probably to be found within its borders. In the Avesta, Margiana is mentioned as one of Ahuramazda's special creations and is referred to as being 'the strong, holy Môuru' (Vendidad, Fargard 1.6). In Hindu, Parsi, and Arab traditions, Margiana is identified with the ancient Paradise. Prior to its late sixth century BC domination by the Achaemenid Persians, Margiana lay immediately outside a much larger and more poorly-defined region known as Ariana, of which the later province of Aria was the heartland. Barely recorded by written history, its precise boundaries are impossible to pin down. It may have encompassed much or all of Transoxiana, the region around the River Oxus (the Amu Darya), and could have reached as far south as the coastline of the Arabian Sea.

Persian Mergu was only a region within Chorasmia which lay to the north. Subsequent Greek domination saw 'Mergu' became 'Margiana' and it also became a separate province. To the east it was bordered by Bactria, to the south-east by Aria, and to the south-west by Hyrcania. By the first millennium BC it may have been populated largely by Indo-Iranian tribes which were migrating east and west from across the River Oxus. Those tribes which remained behind appear to enter the historical record around the sixth century BC, when they came up against their cousins from the rapidly expanding Persian empire.

The Tapuri were a group of people, perhaps something more than a single tribe. They seemingly occupied the southern coastal region of the Caspian Sea around the modern city of Sari but they were claimed as not being Indo-Iranians (sometimes incorrectly). When Media was at its height they formed part of its conquests. When the Persians became dominant they were incorporated with that, lying to the east of the Indo-Iranian Mardoi. During the Greek period they seemingly had their own minor satrapy of Tapouria which was overseen by Margiana. The Tapuri and many other borderland tribes such as the Cadusii, Gelae (Gelonians or Alans), and Utians of northern Media and the shores of the Caspian were classed as Anariaci. The word can be broken down as 'an', meaning 'not', plus 'aria', meaning 'Aryan, Indo-Iranian', and the plural suffix '-ci'. They were the 'not-Indo-Iranians', although the Gelae were indeed Indo-Iranians, if not quite of the same general group as the Persians and Medians. Eventually, though, they were absorbed into the dominant Persian population.

(Additional information from The Marshals of Alexander's Empire, Waldemar Heckel, from Alexander the Great and Hernán Cortés: Ambiguous Legacies of Leadership, Justin D Lyons, and from External Links: Encyclopædia Britannica, and Livius.)

Kingdom of Turan (Indo-Iranian) :

Later myth ascribed a dynasty of Indo-Iranian rulers to this period, as described in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), a poetic opus which was written about AD 1000 but which accessed older works (such as the semi-official seventh century AD book called the Ḵwadāy-nāmag), and perhaps elements of an oral tradition. The Kayanian dynasty of kings of the Persians were also the heroes of the Avesta, which forms the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism. This faith itself had been founded along the banks of the River Oxus, the great river which had probably also formed part of the migratory route used by the Indo-European Persians as they entered Iran.

The earliest of these mythical Indo-Iranian rulers was Fereydun, king of a 'world empire'. His subjects were the Indo-Iranian tribes of the region while his kingdom was apparently in the land of Tūr (or Turaj, sometimes also shown without the accented 'u' as Tur). This can be equated to territory in the heartland of Indo-Iranian southern Central Asia and South Asia, focused mainly on the later provinces of Bactria and Margiana, along with the Kopet Dag region (a mountain range which serves to separate modern Turkmenistan and Iran), the Atrek valley (which supplies an easy route into eastern Iran and is a weak point in the country's defensive line), and the eastern Alborz Mountains (stretching from modern Azerbaijan, along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea, and into Hyrcania and the edges of eastern Iran).

Judging by those borders, the land of Tūr stretched from Samarkand to Tehran, although the kingdom of Turan was probably a good deal smaller and more eastern-based (note the similarly between 'Turan' and Tehran'). The Persians themselves may still have controlled a good deal of the western section as they began to settle in southern Iran. Curiously (and probably not coincidentally), these borders would have placed it on the northern border of another ancient region, that of Ariana, while the land of Aryana Vaejah that is mentioned in the Avesta is usually located to the north and west of both the other two lands.

Fereydun became the father of three sons; Tūr, Salm, and Iraj. Tūr murdered Iraj, thereby triggering an unending feud between the two lines of their descendants. One of Tūr's descendants (possibly a seven-times grandson) was Afrasaib, who ruled the kingdom of Turan during the lifetime of the Persian Kai Kavoos of the seventh century. The stories regarding Turan show it to be in competition with the Persians for mastery of the eastern lands, with many battles being fought. Ultimately it is the Persians who emerge victorious, although the Shahnameh may be showing some bias - history is written by the victorious, after all. Turan's kings are shown with a shaded pink background to denote their legendary status.

(Additional information from Central Asia: A Historical Overview, Edward A Allworth (Duke University Press, 1994), from The Paths of History, I M Diakonoff (Cambridge University Press, 1999), from Islamic Reference Desk, Emeri 'van' Donzel (Brill Academic Publishers, 1994), from Farāmarz, the Sistāni Hero: Texts and Traditions of the Farāmarznāme and the Persian Epic Cycle, Marjolijn van Zutphen, and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Iranians & Turanians in the Avesta.)

Fereydun / Faridun / Fareidun : Ruled a 'world empire'. Abdicated in favour of Manuchehr.

Tūr : Son of Fereydun. Gifted Central Asia. Killed Iraj of Persia.

Thanks to the murder of Iraj by Tūr and Salm, the Persians retaliate under the command of Iraj's grandson, Manuchehr. One of the leading warriors under his command may be Garshāsp (possibly also known as Karāsp), a figure of the Shahnameh or Shahnama, the Book of Kings and a possible descendant of the mythical Indo-Iranian King Jamshid. Tūr and Salm cross the Oxus to face Manuchehr's army on the border between Iran and Turan. The ensuing battle results in heavy casualties for the Turanians, and Tūr is later ambushed and beheaded. Salm is later captured and also beheaded.

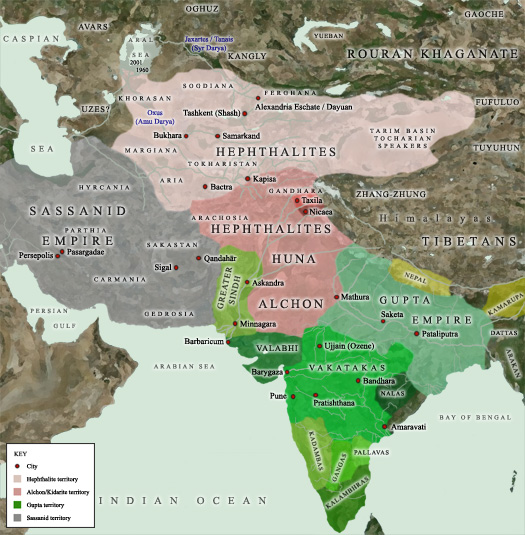

Following the climate-change-induced collapse of indigenous civilisations and cultures in Iran and Central Asia between about 2200-1700 BC, Indo-Iranian groups gradually migrated southwards to form two regions - Tūr (yellow) and Ariana (white), with westward migrants forming the early Parsua kingdom (lime green), and Indo-Aryans entering India (green) Pashang : Grandson. Continued the war against the Persians.

7th cent BC :

Afrasiab : Son. Defeated and died. The story of Afrasiab's eventual defeat and death comes largely from the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings). He is repeatedly defeated by Kai Khosrow (his own grandson via his daughter, Farangis). Forced out of his own lands he wanders wretchedly, taking refuge in a cave known as the Hang-e Afrasiab (meaning the 'dying place of Afrasiab'), on a mountain in Azerbaijan. Ultimately, he is killed by the divine plant of Zoroastrianism, Haoma, near the Čīčhast (location uncertain, but proposed as Lake Hamun in Sistan, which contradicts his location in Azerbaijan). He meets his death in the cave.

7th cent BC :

Sijavus / Siyavash : Son of Kai Kavoos of Persia, and son-in-law of Afrasiab. Sijavus is a legendary Persian prince and the son-in-law of the mythical Afrasiab, the hero and king of Turan. Due to the treachery of his stepmother, Sudabeh, Sijavus exiles himself to Turan (presumably well before the defeat and death of Afrasiab). There, he marries Farangis, Afrasiab's daughter, but the king later orders Sijavus to be killed. His death is avenged by his son, the very same Kai Khosrow mentioned above, who inherits the early Persian throne. c.546 - 540 BC :

The defeat of the Medes opens the floodgates for Cyrus the Great with a wave of conquests, beginning in the west from 549 BC but focussing towards the east of the Persians from about 546 BC. Eastern Iran falls during a more drawn-out campaign between about 546-540 BC, which may be when Maka is taken (presumed to be the southern coastal strip of the Arabian Sea). Further eastern regions now fall, namely Arachosia, Aria, Bactria, Carmania, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Gandhar, Gedrosia, Hyrcania, Margiana, Parthia, Saka (at least part of the broad tribal lands of the Sakas), Sogdiana (with Ferghana), and Thatagush - all added to the empire, although records for these campaigns are characteristically sparse. The inference is very clear - whatever control of Turan the Persians had enjoyed following the death of Afrasiab, it did not last and the lands now have to be conquered properly. Persian Satraps of Mergu (Margiana) :

Conquered in the mid-sixth century BC by Cyrus the Great, the region of Margiana was added to the Persian empire. Before that it was populated largely by Indo-Iranian tribal groups. Under the Persians it was formed into an official satrapy or province which was called Mergu (or sometimes Mergush - Margiana is a Greek mangling of the name, while the Indo-Iranian version has survived as the present day Merv).

These eastern regions of the new-found empire were ancestral homelands for the Persians. They formed the Indo-Iranian melting pot from which the Parsua had migrated west in the first place to reach Persis. There would have been no language barriers for Cyrus' forces and few cultural differences. Although details of his conquests are relatively poor, he seemingly experienced few problems in uniting the various tribes under his governance. He was the first to exert any form of imperial control here, although his campaign may have been driven partially by a desire to recreate the semi-mythical kingdom of Turan in the land of Tūr, but now under Persian control. Curiously the Persians had little knowledge of what lay to the north of their eastern empire, with the result that Alexander the Great was less well-informed about the region than earlier Ionian settlers on the Black Sea coast had been.

The great satrapy of Bakhtrish (Bāxtri) with its capital at Bactra usually had satraps appointed who were Achaemenid princes or members of the highest social elite. Information about the satrapy's administration comes predominantly from the time of Alexander's campaign. The minor satrapy of Mergu was also under the oversight of the satrap of Bakhtrish, as apparently was much of the Central Asian region, as proven by the Behistun inscription. Mergu's core was the oasis at the Margu or Murḡāb, the present-day Marv or Mary in Uzbekistan. Of its borders, only that along the Oxus (Amu Darya) to the north and east can be determined with any accuracy. Those with the neighbouring provinces of Haraiva, Uwarazmiy, and Verkâna are much less precise.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Persica, Ctesias of Cnidus (original work lost but a section is repeated by Photius in ninth century AD Constantinople), from Farāmarz, the Sistāni Hero: Texts and Traditions of the Farāmarznāme and the Persian Epic Cycle, Marjolijn van Zutphen, and from External Links: Encyclopaedia Iranica, and The Geography of Strabo (Loeb Classical Library Edition, 1932), and The Natural History, Pliny the Elder (John Bostock, Ed), and Livius.org.)

522/521 BC :

The usurper Gaumata (Smerdis) takes control in Persis in 522 BC. All three of the oldest sources (Darius the Great, Herodotus, and Ctesias), agree that he and the magi are overthrown within a year or so by Darius and others (normally seven of them) in a coup.

The central relief of the North Stairs of the Apadana in Persepolis, now in the Archaeological Museum in Tehran, shows Darius I (the Great) on his royal throne (External Link: Creative Commons Licence 4.0 International) Immediately afterwards, while Darius is still consolidating his new position, Fravarti the Cyaxarid tries to restore Median independence. He is defeated by Persian generals and is executed. The same happens in Armina, Parthawa, and Verkâna whose inhabitants, as Darius reports, had also joined Fravarti. The quashing of the insurrections from Armina to Parthawa is chronologically coordinated in Persian records and occurs between May and June 521 BC.

522/521 BC :

Frada : Rebel made 'king' by his supporters. Defeated. Another major rebellion takes place in Mergu (referred to as Margush in this instance) towards the end of 522 or 521 BC (scholars disagree over the year, although it is agreed that the rebellion is put down in December). Darius sends against him Dadarshish, satrap of Bakhtrish, and the rebellion is duly crushed. The casualty figures given for the final battle are extremely high - too high for a scratch army of rebels from Mergu. Speculation has suggested that Saka allies of the rebels are involved in the battle, or that the region's capital at Merv witnesses the slaughter of its inhabitants as punishment for joining a province-wide rebellion. 479 - 465 BC :

Xerxes apparently adds two new regions to the Persian empire during his reign, neither of which are very descriptive or clear in their location. The first is Daha, from 'daai' or 'daae', meaning 'men', perhaps in the sense of brigands. Daha or Dahae would appear to be the region on the eastern flank of the Caspian Sea, bordered by the Saka Tigraxauda to the north, and the satrapies of Mergu, Uwarazmiy, and Verkâna to the north-east, south-east, and south respectively. It contains a confederation of three tribes, the Parni, the Pissuri, and the Xanthii. 360s/350s BC :

Artaxerxes II is occupied fighting the 'revolt of the satraps' in the western part of the empire. Nothing is known of events in the eastern half of the Persian empire at this time, but no word of unrest is mentioned by Greek writers, however briefly. Given the newsworthiness for Greeks of any rebellion against the Persian king, this should be enough to show that the east remains solidly behind the king. It seems that all of the empire's troubles hinge on the Greeks during this period.

Artaxerxes II of Persia is immortalised in relief at the entry to his tomb in Persepolis, having survived a reign that began with a series of revolts and included war against the troublesome Greeks (External Link: Creative Commons Licence 2.0 Generic) 330 - 328 BC :

In 330 BC Mergu becomes part of the Greek empire, with Bessus, self-styled 'king of Asia', withdrawing eastwards to make a stand there. His claim as the successor to Darius III is legal, since his satrapy of Bakhtrish is traditionally commanded by the next-in-line to the throne and he has already murdered Darius, but Persia has already been lost and his loose collection of eastern allies - which includes the other two most senior officials, Barsaentes of Harahuwatish and Satibarzanes of Haraiva - provides nothing more than a sideshow to the main event - the fall of Achaemenid Persia. Still, it takes Alexander the Great two more years to fully conquer the region. Argead

Dynasty in Margiana :

The Argead were the ruling family and founders of Macedonia who reached their greatest extent under Alexander the Great and his two successors before the kingdom broke up into several Hellenic sections. Following Alexander's conquest of central and eastern Persia in 331-328 BC, the Greek empire ruled the region until Alexander's death in 323 BC and the subsequent regency period which ended in 310 BC. Alexander's successors held no real power, being mere figureheads for the generals who really held control of Alexander's empire. Following that latter period and during the course of several wars, Margiana was left in the hands of the Seleucid empire from 312 BC.

Margiana was one of the less important satrapies, a minor position that was generally under the oversight of the satrap of Bactria. Apparently much of the Central Asian region was also subservient to Bactria, as proven by the Behistun inscription. Margiana's Achaemenid borders seem to have been maintained under Alexander's control. Its core was the oasis at the Margu or Murḡāb, the present-day Marv or Mary in Uzbekistan. Only the border along the Oxus (Amu Darya) to the north and east can be determined with any accuracy. Those which were shared with the neighbouring provinces of Aria, Chorasmia, and Hyrcania are much less precise. It is even questionable that Margiana was a separate entity during this period. No satraps are listed, so it could just as easily have been controlled directly from Bactria.

Tapouria was a minor satrapy which, if attempts to locate its people - the Tapuri - are correct, was positioned on the southern coast of the Caspian Sea around the modern city of Sari. They would have been wedged between the westernmost parts of Margiana and the northern-western borders of Hyrcania, so one or the other would have seen to their administration. Only one satrap is known, a Greek by the name of Autophradates who was appointed to the position once Alexander had secured the heartland of Persia. After that the region drifted into obscurity.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from The Persian Empire, J M Cook (1983), from The Histories, Herodotus (Penguin, 1996), from Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire, Waldemar Heckel (Ed), and from External Link: Encyclopaedia Iranica.)

330 - 323 BC :

Alexander III the Great : King of Macedonia. Conquered Persia.

323 - 317 BC :

Philip III Arrhidaeus : Feeble-minded half-brother of Alexander the Great.

317 - 310 BC :

Alexander IV of Macedonia : Infant son of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

330 - ? BC :

? : Satrap of Margiana? Name unknown.

330 - ? BC :

Autophradates : Greek-appointed native satrap of Tapouria.

320s BC :

At this time the Sakas appear to reside midway between modern Iran and India, or at least the Amyrgian subset or tribe does. Achaemenid records identify two main divisions of 'Sakas' (an altered form of 'Scythians', these being the Saka Haumavarga and Saka Tigraxauda, with the latter inhabiting territory between Hyrcania and Chorasmia in modern Turkmenistan.

Sakas (otherwise known as 'Scythians' who in this case can be more precisely identified as Indo-Scythians) depicted on a frieze at Persepolis in Achaemenid Persia, which would have been the greatest military power in the region at this time, while above is the route of Alexander's ongoing campaigns across the ancient world 314 - 311 BC :

The Third War of the Diadochi results because the Empire of Antigonus has grown too powerful in the eyes of the other Greek generals, so Antigonus is attacked by Ptolemy (Egypt), Lysimachus (Phrygia and Thrace), Cassander (Macedonia), and Seleucus (Babylonia). The latter re-secures Babylon itself and the others conclude peace terms with Antigonus in 311 BC. 308 -301 BC :

The Fourth War of the Diadochi soon breaks out. In 306 BC Antigonus proclaims himself king, so the following year the other generals do the same in their domains. Polyperchon, otherwise quiet in his stronghold in the Peloponnese, dies in 303 BC and Cassander of Macedonia claims his territory. The war ends in the death of Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. Seleucus is now king of all Hellenic territory from Syria eastwards, turning Alexander the Great's eastern empire into the Seleucid empire, which includes Hyrcania and Margiana. Macedonian, Parthian, & Sassanid Margiana :

Ancient Margiana could be linked to a semi-mythical kingdom of Turan via the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), a poetic opus which was written about AD 1000 but which accessed older works (such as the semi-official seventh century AD book called the Ḵwadāy-nāmag), and perhaps elements of an oral tradition. The kings of Turan can also be linked to the Avesta, which forms the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism. The stories regarding Turan show it to be in competition with the Persians for mastery of the eastern lands, with many battles being fought. Ultimately it is the Persians who emerge victorious. By the late sixth century Margiana was the Persian satrapy of Mergu.

Alexander the Great's victories over the Persians and his pursuit of Darius III led him deep into the lands of eastern Iran, much of which today form parts of Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Margiana was focussed around the River Murghab (Margos to the Greeks). The river has its sources in the mountains of Afghanistan and flows to the north, into the Karakum desert, where it divides into several branches that disappear into the desert sands. The fertile delta created by the river had been prime farming land since at least the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex of about 2200-1700 BC. It was the Greeks who reorganised Mergu into Margiana (same name as used by a different language), a separate province in its own right. Unfortunately, following the death of Alexander almost none of the names of its satraps seem to be known.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Osservazione sulla monetazione Indo-Partica. Sanabares I e Sanabares II incertezze ed ipotesie, F Chiesa (1982), from History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Janos Harmatta, B N Puri, & G F Etemadi (Eds, Delhi 1999), from The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Michael Alram, Touraj Daryaee, & Elizabeth Pendleton (Eds), and from External Links: The History of Ancient Iran, Richard Nelson Frye (1983), and The Cambridge History of Iran Vol 4, Richard Nelson Frye (Ed, 1975), and The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, Vol 7: The Sassanian or New Persian Empire, George Rawlinson (1875, now available via Project Gutenberg), and The Sasanian Empire (AD 224-651), Blair Fowlkes-Childs (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and Encyclopaedia Iranica, and Livius.org.) c.220 BC :

The realm of Euthydemus of Bactria is a large one, including Sogdiana and Ferghana to the north, and Margiana and Aria to the west. There are indications that from Alexandria Eschate in Ferghana the Greco-Bactrians may lead expeditions as far as Kashgar (a little under three hundred and twenty kilometres (two hundred miles) due east of Ferghana), and Urumqi in Chinese Turkestan. There they would be able to establish the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC.

Even more remarkably, recent examinations of the terracotta army have established a startling new concept - the terracotta army may be the product of western art forms and technology. An entire terracotta army plus imperial court are manufactured using five workshops and a form of human representation in sculpture that has never before been seen in China. Archaeologists today continue the process of discovering new pits and even a fan of roads leading out from the emperor's burial mound, one of which, heading west, may be a sort of proto-Silk Road along which Greek craftsmen may be travelling.

Marco Polo's journey into China along the Silk Road made use of a network of east-west trade routes that had been developed since the time of Greek control of Bactria 212 - 209 BC :

Having defeated his rebellious cousin in Anatolia, Antiochus III of the Seleucid empire concentrates on the northern and eastern provinces of the empire. Xerxes of Armenia is persuaded to acknowledge his supremacy in 212 BC, while in 209 BC Antiochus invades Parthia. Its capital, Hecatompylos, is occupied and Antiochus forces his way into Hyrcania, with the result that the Parthian king, Arsaces II, is forced to sue for peace. 167 BC :

Under Mithradates the Parthians rise from obscurity to become a major regional power, although a precise chronology is not possible. Their first expansion takes the former province of Aria from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. It seems possible that Aria (and possibly a rebellious Drangiana too) had already been conquered once by the Arsacids, with the Greco-Bactrians recapturing it, probably during the reign of Euthydemus I Theos. During the reign of Eucratides I the Greco-Bactrians are also engaged in warfare against the people of Sogdiana, showing that they have lost control of that northern region too (and by inference Ferghana).

The other eastern provinces, all of which still appear to be in Seleucid hands, must also fall to the Parthians very quickly after this - including Carmania, Gedrosia, and Margiana - although firm evidence to show a specific date appears to be lacking. Another date which may be valid for these losses is 185 BC, when Seleucus IV loses eastern Iran to Parthian expansion, but the fact that the Parthians fail to expand out of their initial conquests until Mithradates accedes makes this period a more likely one. 115 - 100 BC :

With Parthian territory having been harried for years by the Sakas, King Mithridates II is finally able to take control of the situation. First he defeats the Greater Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BC, and then he defeats the Sakas in Parthia and around Seistan (in Drangiana) around 100 BC. After their defeat, the Greater Yuezhi tribes concentrate on consolidation in Bactria-Tokharistan while the Sakas are diverted into Indo-Greek Gandhar. The western territories of Aria, Drangiana, and Margiana would appear to remain Parthian dependencies. Carmania would also now seem to be Parthian hands.

By the period between 100-50 BC the Greek kingdom of Bactria had fallen and the remaining Indo-Greek territories (shown in white) had been squeezed towards eastern Punjab. India was partially fragmented, and the once tribal Sakas were coming to the end of a period of domination of a large swathe of territory in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India. The dates within their lands (shown in yellow) show their defeats of the Greeks that had gained them those lands, but they were very soon to be overthrown in the north by the Kushans while still battling for survival against the Satvahans of India c.AD 50 - 65 :

Sanabares of Parthia : Satrap of Margiana. Rebelled as rival for Parthian throne.

c.AD 50 - 65 :

Sanabares starts out as the Parthian satrap of Margiana and, being an eastern Parthian, is sometimes included as one of the rebellious Indo-Parthian rulers. At some point he rebels against the weak Parthian king during a period in which the throne is witnessing a constant succession of incumbents and anyone who is a member of the Arsacid family may mount their own claim if they have enough backing.

At his satrapal capital of Merv, Sanabares starts minting his own coins around AD 50, with these coins being the only clear indication of his rebellion in terms of historical sources (he titles himself 'Great King of Kings'). It takes until AD 65 before the latest Parthian king in the west, Vologeses I, can restore central authority in Margiana, at least to an extent. c.213 - 216 :

After perhaps five-or-so years of relative peace Parthian king Vologeses VI has to fight his younger brother, Artabanus in yet another royal rebellion. In AD 216, Rome's Emperor Caracalla asks Artabanus for the hand of his daughter in marriage, in itself clear evidence of the fact that the latter is then regarded as being the ruling monarch, even though the coinage of Vologeses continues to appear in Seleucia until at least 221/2. It would seem that Vologeses is ousted from the heartland of Parthian territory by his brother, but is still strong enough to secure a rival kingdom at Seleucia.

The fractured Parthian empire is breaking down now. With the claim to rule it already dividing the empire in two on official lines, other minor kingdoms have already started emerging or will soon do so. For the moment they probably acknowledge Parthian overlordship in name, but essentially they are probably all but independent states in their own right. At least three are known - Carmania (ruled by a certain Balash), Margiana (ruled by one Ardashir), and Persis (ruled by one Papak of the Sassanids).

fl 224 :

Ardashir : King of Margiana. Submitted to the Sassanids.

224 :

Having been all but independent for some time, Margiana is currently ruled by one Ardashir who is to be differentiated from Ardashir I of the Sassanids. Following the Sassanid victory over the Parthians at the Battle of Hormozdgān, the Sassanids have become the great power in Persian lands. Ardashir of Margiana now submits to Ardashir I. Margiana is permitted to continue minting its own coinage for now, while the Sassanids are still consolidating their power.

Ancient Merv, the capital of Persian and Greek Merv/Margiana, was eventually abandoned just like its even more ancient forebear shown here, Gonur Tepe (Gonordepe), which was a major city of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex until the River Murghab changed its course to leave it high and dry c.230 - 250 :

The end of Kushan King Vasudeva's reign in AD 207 apparently coincides with the beginning of the Sassanid invasion of north-western India, although the dating for the main invasion fits with Vashiska and his successor around 230-250. Perhaps there is a first, preliminary invasion followed by a much greater second.

The Kushans are toppled in former Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria (more recently better known as Tokharistan) and are forced to accept Sassanid suzerainty, being replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the Kushanshahs or Indo-Sassanids. There is a split in Kushan rule, so that a separate, eastern section rules independent of the Sassanids, while some of the nobility remain in the west as Sassanid vassals. Even so, Kushan power still gradually wanes in India. ? - c.260 :

? : Last king of Margiana. Submerged by Sassanids.

c.260 :

Margiana is formally annexed to the Sassanid crown by Shapur I. The name of the vassal king here is unknown (unless Ardashir is still alive). Now Shapur places his own son, Narseh, as governor of the province of Hind, Sagistan, and Turgistan. Margiana is part of this broad territory, falling within the Sagistan section which itself is named for the Saka groups which formerly dominated here.

c.260 - ? :

Narseh : First Sassanid governor of Hind, Sagistan, and Turgistan. c.421 - 427 :

While Bahram V has been occupied by the fighting against Rome, the Kidarites and Hephthalites invade and occupy Sassanid territory in eastern Iran, with the Hephthalites at least occupying Merv (precise details are typically lacking). Having agree peace terms with Rome in 422, Bahram quickly assembles a fresh army to take east. Merv, the capital of Margiana, is captured and the Hephthalite ruler is killed. The Sassanid eastern frontier is fully secure by 427 and a pillar of thanks is erected on the banks of the Amu Darya - the northern limits of Sassanid control. 484 - 560 :

Shah Peroz again chases the Hephthalites out of Bactra in 484 and towards Arion in Aria (Alexandria Ariana, modern Herat). Along the way he destroys the tower built by Bahram V which marks the border between Sassanid and Hephthalite. On the other side of the border, Hephthalite King Khushnavaz sets a trap into which Peroz falls (literally), along with around thirty of his sons and about 100,000 troops. Their bodies are never recovered by the Sassanids. The eastern empire is overrun and is largely occupied by the Hephthalites until their final fall - this includes regions such as Margiana and its rich capital at Merv, with the Hephthalites setting up puppet governors.

By the late 400s the eastern sections of the Sassanid empire had been overrun and to an extent occupied by the Hephthalites (Xionites) after they had killed Shah Peroz 631 - 651 :

Mesopotamia is lost to the Arabs in 637. The Sassanids are defeated at the Battle of Nahāvand by Caliph Umar in 642. Persia is overrun by Islam by 651. Retreating into Margiana, Sassanid King Yazdagird finds few allies and is forced to retreat again. Organising a hurried alliance with the Hephthalites, he advances towards Margiana, only to be defeated at the Battle of the Oxus. Yazdagird takes refuge in a mill, where the owner kills him while his family flee to Turkestan. The Sassanid empire has fallen.

Much of what formerly formed the eastern regions of the Persian empire now falls to Islam. The old province of Chorasmia is now recreated as an expanded 'Greater Khorasan'. Many of the eastern regions are ruled from there, including Margiana which effectively disappears from history as far as its previous identity is concerned. Russian

Central Asia (Turkmenistan) :

Interest by imperial Russia in Central Asia was only really kindled after 1783 when, despite having guaranteed its independence in 1774, Catherine the Great now formally annexed the khanate of Crimea. The move was primarily to remove any possibility of the rival Ottoman empire dominating the region, but it also opened the way to further moves into the Caucuses and the Caspian steppe. This move effectively formed a prelude to the 'Great Game' of the nineteenth century's imperial age, in which the major powers would vie for territory and influence.

During the second half of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth, Russia gradually dismantled the Kazakh territories in northern Central Asia. In 1839 they pursued a renewed policy of pressuring the Ottoman empire and Britain for control of southern Central Asia. An abortive mission was sent to Khiva, purportedly to free slaves who had been captured from areas of the Russian frontier and sold by Turkmen raiders. Britain was already involved in the First Anglo-Afghan War in Afghanistan but, despite sending over five thousand infantry, the Russian force stumbled into one of harshest winters in living memory and was driven back by the weather and by its losses. Undeterred, in 1848 Russia built Fort Aralsk at the mouth of the River Syr Darya. From here the empire began a steady process of encroachment upon the lands of Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand. It met stiff resistance all the way but its resources far exceeded those of its opponents.

In 1865 Russia took Bukhara, Tashkent, and Samarkand (all of which went into forming Uzbekistan in 1924). Tashkent was made the capital of a new state of the same name, incorporating much of southern Central Asia into its territory. In 1873, weakened by attacks from Kokend and Bukhara and losing control of the right bank of the Syr Darya, Khiva was finally conquered by Russia on the third attempt. Russian expansion in Central Asia, and towards South Asia, was only halted in 1887 when Russia and Britain agreed the northern borders of Afghanistan.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Indian Frontier Policy, John Ayde (2010), from the Encyclopaedia Britannica, from History of the World: Volume 7, Arthur Mee, J A Hammerton, & Arthur D Innes (1907), from An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples, Peter B Golden (1992), from Inner Asia: History, Civilization, Languages; A Syllabus, Denis Sinor (1969), from History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century, Henry H Howarth (1880), from Kazakhstan, Pang Guek Cheng, from History of the Civilisations of Central Asia - Towards the Contemporary Period: From the Mid-Nineteenth to the End of the Twentieth Century, Chahryar Adle (Ed), Chapter 9 Uzbekistan, D A Alimova & A A Golovanov, Unesco, and from External Links: Encyclopaedia.com, and History of Khiva.)

1917 :

Russia's February Revolution begins with riots in Petrograd over food rations and the conduct of the First World War against the German empire, and it ends with the creation of a Bolshevik Russian republic following the October Revolution. Nicholas II abdicates, first in favour of his son, Alexei, and then in favour of his brother, Michael. The act effectively ends a thousand years of royal rule. Mismanaging their own administration of the country and badly handling the war effort, the Bolsheviks start to lose control of some of Russia's imperial dominions, and the empire slides into civil war.

The Bolshevik revolution plunged the former Russian empire into a civil war which involved several fronts and armies, sometimes almost amounting to several separate wars happening at the same time across the empire's vast territory 1918 - 1921 :

Liberalist and monarchist White Guard Russian forces (including supporters of the 'February' revolution) resist the imposition of a Bolshevik state, and fight a civil war against the Red Guard communist forces. In the newly-formed Tashkent SSR, anti-Bolshevik forces unite to liberate the former khanate of Khiva, the emirate of Bukhara, and Turkestan Krai.

A reorganisation of Central Asian Soviet-controlled states along ethnic lines means the end Khiva, the Turkestan Krai, and Bukhara (the latter being ousted by the Tashkent Soviet in 1920). They are merged into the newly-formed 'Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic', which is formed as a self-governing entity of the early Soviet Union. However, in the same year, the Islamic Council and the Council of Intelligentsia declare the rival 'Turkestan Autonomous Republic', and set about fighting against the Bolshevik forces who start closing down mosques and persecuting Muslim clergy as part of their secularisation campaign.

1921 - 1924 :

The Turkestan Autonomous Republic has gradually lost ground to the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks themselves have been divided into two groups over the region's future, but the idea of a pan-Turkic state is jettisoned in place of several smaller states. In 1924 the Turkestan ASSR is divided into the Uzbek SSR, the Turkmen SSR, the Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast (Kyrgyzstan), and the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast (modern Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic of Uzbekistan). Initially, the Tajik ASSR is also adjoined to the Uzbek state. Modern

Turkmenistan :

Modern Turkmenistan is made up mainly of desert, and has the smallest population of the five Central Asian ex-Soviet republics. Its western border lies on the Caspian Sea. To the north it almost reaches the Aral Sea and is mainly bordered by Uzbekistan, with a divide formed by the River Amu Darya, while what are now Iran and Afghanistan fill its southern and south-eastern borders.

The Black Desert region, or Karakum, was for a while home to Indo-European tribes from further north in Central Asia in the third millennium BC. Living here in vast mud-brick fortress citadels, herding cattle, and worshiping fire in rituals controlled by an early form of Brahmin, they also domesticated and worshipped the horse. Eventually they were forced southwards by climate change between about 2000-1500 BC. The bulk of them seemingly re-emerged in India as the Aryans who created the first documented states there, while some may have formed the proto-Persians and doubtless many others remained where they were to form part of the populations of later states in the region - albeit subsumed within the later-arriving Turkic population.

South-western Turkmenistan lies largely within the former Persian satrapy of Verkâna (Greek Hyrcania) while the eastern section lay partly within Bactria and much more so within Mergu. This area was invaded by Alexander the Great's Greek empire, and Bactria became independent in 256 BC. Following that, the region was occupied by Sakas and Greater Yuezhi, and was controlled by the Kushans and then the Sassanids. With the collapse of the Samanids in the ninth century AD the region became a battleground for vying factions of Turkic tribes, and it was the Turkic-speaking Oghuz who settled Turkmenistan and who today form much of its population. From the end of the tenth century AD the region was largely part of the emirate of Khwarazm, before being divided between the Mongol Il-Khanate and Mughulistan. Timurid Transoxiana claimed it next, and then it formed part of the region of Turkestan which was ruled by the Shaibanid empire in the sixteenth century. This in turn was displaced by the khanate of Khiva and then the Russian empire.

Turkmenistan in the modern sense was formed in 1924, when its Soviet masters divided Khiva and its short-lived successor, the Tashkent ASSR. This included a portion of the territory of the former emirate of Bukhara. The Turkmen SSR survived in that form until the collapse of the Soviet empire. In 1991 Turkmenistan became fully independent, with its capital at Ashgabat. Like the Soviet Union in the years before Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika, both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan now live under regimes that resolutely and brutally resist change. The capital, Ashgabat, soon lost its Soviet appearance, and began to resemble more and more a rather bizarre Las Vegas, with a giant star on top of a Palace of Happiness, and a wedding palace that changes colour. Rich in natural resources, with the world's fourth-largest gas reserves, Turkmenistan can afford this and much more extravagance.

(Information by Peter Kessler, with additional information from Modern Times, H Kahler, and from External Links: BBC Country Profiles, and Lonely Planet, and The New York Times, and from the NOAA.) 1934 - 1939 :

Undaunted by his failures to date, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin directs a massive purge of the Bolshevik party, the armed forces (decimating the officer class), government and intelligentsia. Millions of people, labelled enemies of the state, are killed or imprisoned, with the notoriously harsh gulags in Siberia being used to deposit many thousands of his victims.

By the end of this decade another casualty of Soviet rule is the former pastoral nomadic existence of the Turkmen, now that a sedentary life is the only way to survive. Ethnic Russians are moved into the region, along with other groups from around the Soviet Union, serving to alter Turkmen social and cultural strands. Religious beliefs are attacked and mosques are closed down, but the country is generally peaceful, with many Turkmen continuing to live isolated agrarian lives that are less affected by Soviet oppression. 1948 :

A magnitude 7.3 earthquake strikes Ashgabat in south-western Turkmenistan - formerly an important location for the Blue Horde and White Horde. It makes an orphan of one Saparmyrat Niyazov, future president of Turkmenistan. Reporting of the disaster is strictly limited by the Soviet authorities, perhaps reluctant to admit to any kind of failing. Admiral Ellis Zacharias, former US deputy chief of the Office of Naval Intelligence, claims more than once that the earthquake is the result of the Soviet Union's first atomic bomb test. 1950 - 1953 :

An over-ambitious canal-building programme is launched with the aim of connecting the Aral Sea to the Karakum Desert in order to irrigate it and make its soil productive. With Stalin's death in 1953 it is abandoned in an unfinished state, but work on the equally ambitious Qaraqum Canal begins the following year. In time this effectively drains the Amu Darya and severely diminishes the Aral Sea.

Soviet canal work was generally over-ambitious in scale and highly damaging to the surrounding ecology, especially in this case to the Aral Sea and the River Amu Darya 1985 :

The turnover in general secretaries of a more senior level of experience in the Soviet Union now leaves an opening for younger, more reform-minded individual to make a mark on the Soviet Union. One of Mikhail Gorbachev's first actions is to remove from office Muhammetnazar Gapurow, first secretary of the Communist party in the Turkmen SSR. Unfortunately this leaves an opening for Saparmyrat Niyazov, who becomes a life-long 'dictator of Turkmenistan'.

1985 - 2006 :

Saparmyrat Niyazov : Dictator. 'Turkmenbashi' ('leader of the Turkmen'). Died.

1991 :

Turkmen SSR achieves independence as the Soviet empire collapses. As with neighbouring Uzbekistan's own Communist leader, Turkmenistan's Saparmyrat (or Saparmurat) Niyazov is ready. He hails from Kipchak (or Gypjak), just outside Ashgabat. He makes a smooth transition from Communist Party first secretary to president, keeping a tight lid on his country of 5.1 million while cultivating a bizarre cult of personality.

2006 :

Saparmyrat Niyazov has covered his desert republic with golden statues of himself, and grandiose monuments to the achievements of his 'golden age'. He has also ordered the construction of his own mausoleum, next to a giant mosque, before his death in 2006. Today it is guarded by strictly regimented soldiers similar to those who keep watch over Lenin's tomb on Red Square in Moscow.

Acting President Gurbanguly Mälikgulyýewiç Berdymukhamedov (or Berdimuhamedow) formally succeeds in office after 'winning' the election in 2007 with a largely unopposed majority. This is despite the constitution stipulating that an acting president cannot stand for election. That inconvenient rule is swiftly cancelled by the People's Council in time for the elections.

2006 - Present :

Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov : Dictator. 'Arkadag' ('protector').

2015 :

The Turkmen fascination with specially dedicated grandiose monuments has not ended with the death of Saparmyrat Niyazov. In May 2015 a gold-leaf statue of a mounted President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov perched on top of a vast 'cliff' of rock is unveiled in the capital. However, the new president has cut back the cult of personality, and restored many of Niyazov's more arbitrary cuts. The regime is more open than previously, even though it is still strictly authoritarian.

Source :

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/ |