| SIGNIFICANCE OF KUSTI The Pahlavi term used to designate the “holy cord or girdle” worn around the waist by both male and female Zoroastrians after they have been initiated into the faith.

KUSTI, the Pahlavi term (Pers. kusti, košti, Guj. kusti) used to designate the “holy cord or girdle” worn around the waist (Pahl. kust, Pers. košt “side, waist”) by Zoroastrians. The term glosses Pahl. aiwayahan < Av. “holy cord to wrap around, to girdle”>. It is wrapped three times around the waist and is tied with two square or reef knots, one in the front and then one at the back, by both male and female Zoroastrians after they have been initiated into the faith.

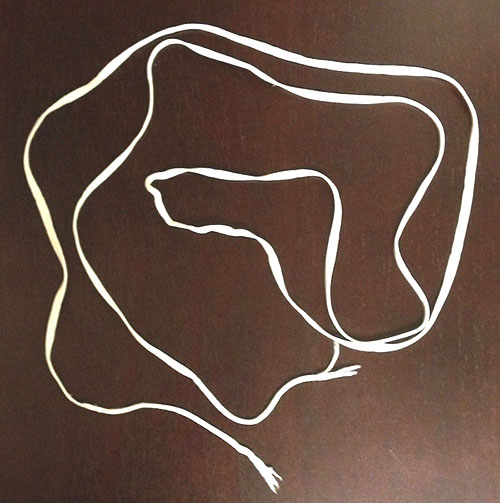

A kustig woven in Kerman, 2003 The kusti is a single cord of six interwoven strands, each made up of twelve white threads of lamb’s or, less frequently goat’s, wool—that is, a total of seventy-two (72) threads. Cotton can be used as well. The six (6) strands are braided together at each end to form three (3) tassels, which contain twenty-four (24) threads each. The holy cord’s symbolism was elaborated over the centuries. The six strands were equated to the six gahanbars or “religious feasts,” the twelve (12) threads to the twelve months of the religious calendar, the twenty-four (24) threads of the tassels to the chapters of the Visperad, and the seventy-two (72) threads of the entire cord to the chapters of the Yasna.

Traditionally, in Iran and India, kustis have been woven by women from athornanor priestly families, both as a pious duty and as a means of supplementing their families’ modest incomes. Sometimes the cords were woven by mobeds or magithemselves—a practice now very infrequent. During the 1920s, behdin or Zoroastrian women in the towns and villages around Yazd were trained to weave the cords. Parsis at the city of Navsari in Gujarat became well known for supplying the holy cords to coreligionists in India and in other Zoroastrian diasporas, such as Great Britain and the United States. As in Iran, income from sale of the cords augments family earnings. Parsi girls attending the Tata Girls’ School at Navsari are still taught how to weave kustis.

Other Parsi women learn the skill from their elders; for example, Mrs. Najamai M. Kotwal, mother of Dastur Dr. Firoze M. Kotwal, instructed Parsi girls for almost three decades. Production of the cords is considered a joyful activity during which the women sing, laugh, and share religious and lay stories.

Tying the kusti around the waist with three encirclements (Pahl. kiš) is believed to represent humat, huxt, huwaršt or “good thoughts, good words, good deeds,” which is the religion’s credo, and thereby serve as a boundary to protect the body against the forces of evil. So it is said to be luminously stehrpaesanha- “star-spangled”, encircling each devotee’s midsection like the zodiac demarcating the axis of the sky. According to the Cim i kusti or “Reasons for the Holy Cord”, a Sasanian-era text preserved in both Pahlavi (or Middle Persian) and Pazand versions: “The place of all beauty, light, and wisdom is the higher part, the head, which like paradise is the station of lights … that lower half, the place of darkness and desolation, is like hell … and the purpose of wearing the holy cord is to demarcate the two regions.” This theme of separating mental from physical recurs in post-Sasanian texts, such as the Gizistag Abališ, when explanations are provided as to why Zoroastrians must always wear the kusti. Essentially a religious symbol transformed into an article of devotional clothing, thekusti and its recurrent exercise of untying and retying remind each wearer about the centrality of piety and the need to follow the religious path throughout life.

Mrs. Najamai M. Kotwal weaving a kustig, Mumbai, 1990 The rite of wearing a kusti probably dates to pre-Zoroastrian times. A similar practice among the Hindus goes back to Vedic ritual, where men of the upper three castes are invested with a holy cord at a religious initiation—the ceremony of the second birth (Skt. upanayana-)—between the ages of eight and twelve. Those Hindus wear the cord diagonally around the body over the left shoulder and under the right arm, slipping it aside when necessary but never untying it. Although a date for the kusti’s introduction into the Zoroastrian faith cannot be determined precisely, its use may have been present among the prophet Zarathushtra’s earliest followers due to their prior familiarity with the practice. Possible origins of its usage are variously mentioned in the Zoroastrian texts. According to the Yasna (10.21), it was introduced by a holy sage named Haoma Frašmi. The Dadestan i denig, on the other hand, attributes its first use to the legendary Pishdadian ruler Yima Xšaeta or Jamšed, centuries before the birth of Zarathushtra; and later Ferdowsi too would echo this tale in the šah-nama. Other legends hold that Zarathushtra commended the custom to those who accepted his preaching.

According to Zoroastrian praxis, a kusti must be worn by every man and woman who has been initiated into the faith through the navjote (also naojote) or “new birth” ceremony among Parsis and the sedra-pušun or “putting on the holy undershirt” ceremony among Iranian Zoroastrians. During that initiation, which represents transition to adulthood and acceptance of responsibility for religious deed thereafter, each boy or girl dons a white undershirt (Pahl. šabig, Pers. šabi, sudra, sedra, Guj. sudra, sudre) and ties a kusti over it around the waist. Thereafter it is a tanapuhl ( sin to not wear the cord and undershirt, for so doing leaves the person unprotected from evil and consequently is equated to “scrambling around naked” (Pahl. wišad dwarišnih) in the Šayest ne šayest and the Nerangestan. The kusti is mentioned in the third of sixteen Sanskrit slokas by Aka Adhyaru as a “good woolen holy cord put on the waist.” The merit accrued from tying the kusti is equated in the thirteenth Sloka to performing “ablution in the [holy River] Ganges.” Compared in the slokas to “a coat of mail armor,” it also serves to ward off evil under other situations. So, during funerals, the kusti is held in hand to create paywand or “ritual connection” between two persons such as corpse-bearers (who hold this cord between them) while the Zoroastrian mourners, also in similar paywand, follow in procession.

Due to its religious roles, not only must the cord be worn every day during the devotee’s lifetime, it needs to be ritually untied and retied with specific prayers after the padyab purificatory ablution—a ceremony called the padyab-kusti which involves “making new the holy cord” (Pers. košti nav kardan) or “tying the holy cord” (Guj. kusti bastan).

While untying and tying the kusti, the devotee should face east from dawn to midday and west until sunset—that is, toward the sun. At night, he or she may face an oil lamp, fire, moon, or stars. In the absence of any source of illumination, facing south is regarded as an appropriate qebla, for it is believed to be the direction to the heavenly abode of Ahura Mazda. The prayers, which are recited during the kusti ritual, are divided into three parts. The first part is called the Nirang i padyab “rite for ritual ablutions.” Recited before untying the cord, it consists of the Kem na Mazda prayer. The second part is called the Nirang i kusti bastan/abzudan “rite for tying the holy cord” which is chanted while ceremonially retying the kusti. The initial Pazand prayer of Ohrmazd Xwaday (up to pa patit hom) is a summary of the previous Kem na Mazda. The prayer ends with a short Avestan passage praising Ahura Mazda and showing contempt for Anra Mainyu as an act of faith, followed by a line taken fromY. 50.11.

This part is completed by reciting one Ašem vohu prayer, two Ya0a ahu vairiio (Ahuna vairiia, Ahunwar), and one more Ašem vohu . The third part, which begins with the words Jasa me avanhe Mazda, constitutes the Zoroastrian confession of faith (MPers. astawanih i den); it also is titled stayišn denih “the praise of religion” in the Pahlavi version. The first line of this prayer is taken from Yt. 1.27 and the remaining portion from Y. 12.8-9. It concludes with the repetition of one Ašem vohu.

The kusti’s ritual efficacy must be renewed through the padyab-kusti ceremony prior to engaging in other religious acts like worshipping at a fire temple, and after sexual intercourse, urination, and defecation. It is untied and retied upon awakening each day, at the beginning of the other watches or divisions (MPers. and Pers. gah) of the day. Most Parsis, even when living in Western countries, still wear the kusti regularly; Iranian Zoroastrians often wear it only for religious services so as not to be singled out for maltreatment by Muslims.

Source :

https://www.ahuramazda.com/ |