| AMAZON WOMEN WARRIORS PART - 7 Note :

The given information is taken from google books and hence, many pages are missing. It is from the book given below :

Post colonial Amazons

Female Masculinity and courage in ancient Greek and Sanskrit Literature

Walter Duvall Penrose, Jr.

Introduction

:

The typical answer has been that women did not really take part in battles. In this line of thought, stories of women fighting men are simply that, stories—not history.2 Legends of Amazons, other women warriors, and warrior queens are usually interpreted using a traditional, Athenian point of view, and thus dismissed. But what if we decenter Athenian understandings of gender in our reading of Greek literature? Might we come to different conclusions in so doing? In this book, I will employ a postcolonial methodology to provincialize Athenian thought and to rethink the veracity of warrior women in a broad, comparative context. Furthermore, while the Amazons of Greek lore were exaggerations, I will demonstrate that they were based upon a Greek under-standing of other cultures wherein women fought and held power. While the Amazons were the quintessential representation of female masculinity in ancient Greek thought, they were by no means the only example of manly/ courageous women. Women whom the Greeks considered to be masculine were masqueraded on the Greek stage, described in the Hippocratic corpus, took part in the struggle to control Alexander the Great's empire after his death, and served as women bodyguards in ancient India and Persia. Looking from the outside in, it is possible to rethink the ancient history of bold and warlike women. In this book, I will seek to excavate the evidence of those women upon whom the Greek phenomenon of the Amazons was based. I will demonstrate that the Amazons were an Orientalized distortion of historical women warriors and warrior queens, and analyze how the Amazons fit into larger paradigms of Greek thought with regard to female masculinity, warrior women, and matriarchy.

The

Amazons :

Whereas Homer (Iliad 3.189, 6.186) considered the Amazons to be the equals of men [antianeirai], Lysias thought that they were even better than men. Despite having inferior strength, they used ingenuity and technology to subdue all of the nations around them, but finally met their match, at least according to Lysias, when they decided to attack Athens (2.5). Lysias asserts that the Athenians put the Amazons in their place by defeating them, and established, finally, that they were indeed women. Plutarch tells us that not even the Athenians could defeat the Amazons, however, but had to make a peace treaty with them (Thes. 27). Furthermore, Plutarch indicates that differing tales of the Amazon invasion of Attica had been circulating for centuries before his time. The legend of the Amazons has inspired awe and sparked the imaginations of countless persons over several millennia. The idea of women fighting and defeating men and living independently of them lies at the heart of this fascination with the Amazons. Aeschylus calls the Amazons "man-hating" [stuganores] and "man-less" [anandroi] (Prometheus Bound 723-4; Suppliant Women 287).

According

to the Greek author Ephorus, who wrote in the fourth century BCE,

the Amazons of Themiscyra opted out of compulsory patriarchy in

the first place because they were ill-treated by men: "The

Amazons were treated insolently by their husbands, and, when some

of the men went to war, the Amazons killed those left behind and

refused entrance to those returning" (FGrHist 70 F 60a).3

In the Roman period, Pompeius Trogus relates that the Amazons, seeing

the ills of their previous marriages, decided to avoid marriage

permanently: "They had no desire to marry their neighbors,

calling this slavery, not matrimony" (apud Justin 2.4). As

single women par excellence, the Amazons did not die out: instead

they found ways to procreate by either crippling males and turning

them into sex slaves who performed domestic labor (Diod. 2.45),

or, in another version of the story, by meeting the men of the Gargarians

once a year to copulate (Strabo 11.5.1). In this scenario, male

offspring were given to the Gargarians, and the Amazons raised the

females. In yet a third version of the story, the Amazons copulated

with the men of neighboring tribes, raised female infants, and killed

male infants. Hence they were called "man-loving" [philandros]

yet "male-infant-killing" larsenobrephokontosj by the

Greek author Hellanicus (FGrHist 4 F 167).

4 Amazons, it would seem, could not exist unless they were sexually independent of or masters of men, although they do ally with men to fight, including Trojans and Scythians (Arctinus Aithiopus, apud Proclus Crestomathia 2; Dictys of Crete The Trojan War 4.2, ed. Eisenhut; Isoc. 12.193; Diod. 2.45, 4.28.2; Just. 2.4, ed. Seel).

5 Of course, Greek legends tell us more about who the Greeks thought the Amazons were than they do about the actual women who formed the basis of the Amazon myth. Nevertheless, lurking behind the myths there is an "historical core."6 In a number of texts, the Amazons are associated with the Scythians, a historical, nomadic people who lived in the Eurasian steppes. Writing some 300 years after Lysias, Diodorus added a new twist to the story of the Amazons attacking Athens. According to Diodorus, the Amazons did not attack Athens alone. Rather, they did so with the Scythians at their side (4.28.2). In other texts, the Amazons are seemingly interchanged with the Scythians. Whereas Lysias asserts that the Amazons were the first in their region to harness iron to make war, Hellanicus tells us that the Scythians were the first to make iron weapons (Lys. 2.4, Hellanicus FGrHist 4 F 189). Accor-ding to Diodorus, the Amazons conquered all the way from Thrace in the north to Syria in the south, whereas the Scythians conquered from Thrace to Egypt (2.44-6)7 Just as the Amazons engaged in warfare according to Lysias (2.4), Scythian women trained "for warfare like the men" according to Diodorus (2.44). As mentioned above, according to Herodotus, the Amazons eventually even married the Scythians, but in so doing formed a new tribe, the Sauromatians (Hdt. 4.114-117).

It is starting to sound more and more as though the Amazons and the Scythians were conflated in ancient thought. One could perhaps argue that the Amazons were Scythians,8 The problem with this hypothesis, however, is that the Amazons were associated with other peoples as well. In Greek literature, Amazons allegedly behave like the Sauromatian women, for example in cauterizing their breasts, engaging in warfare, and dominating men.9 Then again, they wear Thracian outfits on Greek vases, and the Amazon Penthesilea is described as "Thracian by race [genos]" (Arctinus Aithiopus, apud Proclus Crestomathia 2).10 In early legends, the Amazons lived along the river Ther-modon, a place where Asian Thracians apparently also lived.11 But then again, in a later version of the myth, the Amazons lived in the same place as the Libyan tribe of the Auseans, near Lake Tritonis (Diod. 3.53; Hdt. 4.180). Like Amazons, the young women of the Auseans fought.

While the Amazons are an "other" to the Athenians, among whom women were delegated roles as housewives, they seem to have comparable customs and a similar history to more historical women warriors. Archaeology has opened new windows onto these issues. In the past century and a half, archaeologists have excavated graves of Scythian, Sauromatian, and Thracian women buried with weapons, women whom they have labeled "Amazons." 12 Meanwhile, Western art historians and literary scholars largely came to the consensus that the Amazons were a fabrication of the Greek imagination. These diverging disciplinary perspectives can be brought together, however. In this book, I will demonstrate that women were taught to wield weapons and did in fact fight in numerous locations known to the Greeks. I will explore the ways in which various warlike and powerful women were turned into Amazons and matriarchs by the Greeks. I will resituate "Amazons," matriarchs, and various other courageous warrior women within the very social contexts from which they all too often have been extracted. By extending the geographical scope of analysis beyond Athens to the wider world known to the Greeks, I hope to show that Athenian gender norms were not shared by others. The legend of the Amazons may be exaggerated, but the customs that fostered it have bases in historical truth. The Amazons, I will argue, are a conglomeration of the customs of a broad swath of peoples, peoples that can be described largely as nomads.13 We are left wondering how and why the Greeks conflated all of these different customs and peoples into the Amazons. The answer must be related to the Greek tendency to mythologize, as well as to Greek discom-fort with what they perceived to be masculine women.

Orientalism and Amazons :

The Greek understanding of the Amazons as masculine is, ultimately, an Orien-talist interpretation. The Greeks did not understand a way of life that necessitated women riding, herding, and fighting. We do not know what nomadic women warriors would have thought of themselves, but we can and do see inconsistencies in Greek literature that describes such "barbarians." Whereas archaeological evidence of warrior women in Scythia and Central Asia suggests that women had more equality with men than in Greek societies, the Greeks understood such differences from within their own interpretive framework. Even the evidence that the Greeks provide does not necessarily reinforce their seemingly biased claims of dominant, matriarchal women effeminizing weak, "barbarian" men. Some level of ethnocentrism is involved in the discrepancy between the facts recorded by the Greeks and their interpretation of them.

According to Said, "The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.14 Nevertheless, Said himself warns that "it would be wrong to conclude that the Orient was essentially an idea, or a creation with no corresponding reality."15 The Occident and the Orient exist, to some extent, as reflections of one another. Just as Said notes that "Orien-talism derives from a particular closeness experienced between Britain and France and the Orient" in the modern period,16 so too did ancient Greek Orientalism derive from a closeness experienced between Greeks and "bar-barians," with whom the Greeks traded and on whose land they founded colonies, many of which began as trading posts.17 The Greeks filtered their understandings of non-Greek customs through their own misogyny, however, and, due to their own binary, polarized gender ideology, took the figure of the barbarian woman warrior and recast her as the Amazon.

To the Greeks, the term "barbarian" initially simply meant "non-Greek," but over time the word took on negative connotations. By the fifth century BCE, "barbarian" men were increasingly seen as effeminate by Greeks, and, in this view, were dominated by strong women.18 Because Athenians and other Greeks could not understand a society where men allowed women to fight or hold power, they assumed that women warriors either murdered or dominated men.

Like

the modern Orient of Said, however, the barbarian world known to

the Greeks had a basis in historical truth. While Orientalism, or

the theory of the "other" more generally, may have much

to tell us about Greek views of other peoples, another approach

might be more useful in unearthing barbarian histories.19 Said has

been criticized for theorizing an overly simplistic divide between

the Occident and the Orient.20 In a similar fashion, analyses of

ancient Greek texts and artwork have all too often been over-reliant

on a binary division between self and other, theorizing a rigid

division between Greeks and barbarians.21 A quotation from a recent

work by Robin Osborne illustrates how this tendency continues to

hold sway in the profession of classics in the twenty-first century.

When describing the aspirations of Athenian vase painters, Osborne

makes the following comment:

Indeed, vase-painters, like any other past peoples, may have been ethnocentric. That said, cannot Greek images, and correspondingly texts, tell us more about others than just what it meant to be Greek? Were the Greeks completely self-absorbed, or have we ourselves as modern classicists been completely absorbed in the Greeks at the expense of other historical peoples with whom the Greeks were fascinated? As some critics have recently suggested, problematizing the binary relationship between Greek self and other may be fruitful.23

In this vein, I will differentiate between Athenian and other Greek (e.g. Argive, Halicarnassian) gender ideologies (Chapters 1 and 4), as well as problematize the binary relationship between Greeks and others, particularly Amazons and "barbarian" warrior queens (Chapters 2-6)24 Although the Greeks certainly did engage in binary thought, I will strive to make clear that the Greek legends of the Amazons rely upon much more than just a binary inversion of Greek norms.25 The legends of the Amazons are cultural constructions that draw upon stories and customs of many barbarian peoples, including Scythians, Sauromatians, Thracians, and Libyans.26 Thus it is my claim that the stories of the Amazons are more than just an "other" through which the Greeks defined themselves, as has often been argued; they are facsimiles of narratives of numerous other peoples among whom women fought.27 As Otto Brendel once wrote to Larissa Bonfante: "We take the Greeks as our model, forgetting that the Greeks did everything differently from everyone else."28 "Barbarians" had different customs than the Athenians, even if these customs were exaggerated by the Greeks. Thus, a binary "other" approach towards studying the Amazons oversimplifies the system of thought used by the Greeks.

Whereas structuralists theorized systems of thought as an "array of binary oppositions (pairs of opposites that structure and provide stability to systems), post-structuralists, also known as deconstructionists, saw everything as mul- tiple," and understood systems of thought as "endlessly mobile and unstable." 29 Deconstructionists thus noted the oversimplifying tendency of structuralism. Postcolonial studies has appropriated these post-structuralist points of view: whereas Said largely theorized the Occident and Orient as binary oppositions, recent postcolonial theorists, following post-structuralists, have rethought the framework through which we analyze self and others, Greeks and barbarians. 30 Similarly, whereas modernist discourse focused upon metanarratives, post- modernist analyses have focused attention upon the fragmented nature of such master narratives, and emphasized local variations as opposed to singular or overly systematic world views.31

In antiquity, Amazon narratives shifted and changed over time. Furthermore, there were multiple Greeks and multiple others. In this perspective, the legends of the Amazons are products of cultural interaction among multiple Greeks and multiple others. Past analyses of Amazons have been largely conducted in a binary fashion, where the "other" defines the Greek self through a complete inversion of norms. Blok argues that despite the systematic discourse of the theory of the other, "Amazonology remains internally inconsistent. Even the procedure of inversion ... is anything but consistently present" in the Amazon myths. "The distinction between the group of Amazons (women) and Gargarians (men with their own women but available as sexual partners for the Amazons) has no inverted precedence in the Greek context." 32 In another sense, the segregation of the Amazons from the Gargarian s is more similar to the isolation of Athenian women from men than it is opposite. Furthermore, as I will demonstrate, the usage of the word "Amazon" was not fixed—the term was a Greek label that was used to refer to others in an inconsistent manner. It was used for other, more historical peoples, and could mean different things to different authors. For all of these reasons, I will utilize a post-structuralist, postmodernist, postcolonialist approach that problematizes and rethinks the received "theory of the other" that has been so prevalent in the filed of classics for the past forty or more years.

Orientalism

and Matriarchy :

Historical warrior women, ranging from nomads to warrior queens to Greek women defending their homes from the onslaught of invaders, root Greek legends of the Amazons in some historical reality. While women who fought or were otherwise courageous were considered masculine by the Greeks, the truth may be that they were simply responding to the daily needs of their own lives. War was a way of life in the ancient past, and women were not immune to it.

On the one hand, the Amazons are representations of female masculinity and matriarchy—phenomena that were troubling to some Greeks. As a result, the Amazons are usually killed off in Greek literature and art to restabilize patriarchy, which they upset. On the other hand, "Amazons" and matriarchs are Orientalized distortions of real women warriors and warrior queens, women who may have viewed themselves differently from the way they were seen by the Athenians. They may not have been called masculine by their immediate peers, but, due to a lack of written records, we may never know for sure.

Female

Masculinity :

35 While effeminacy in Greek men, barbarians, and even slaves has been a hot topic of discussion in recent scholarship on ancient Greece, perceived mascu-linity in women has received far less attention. Part of this may stem from the fact that male gender variance "is more frequently culturally emphasized than female gender variance.... In patriarchal societies, the social status gained by" male-to-female transgender individuals "appears less threatening to society than the social status lost by" female-to-male transgender persons, "and helps account for the cultural focus on male gender nonconformity."' But there is another reason for this lack of scholarly focus on female masculinity. The term "masculinity" is derived from a set of behaviors, norms, and customs expected of men. Masculinity and masculine behavior have been noted in women for thousands of years; however, the study of masculinity in women has been stymied by a false understanding that masculinity is the product of men only and, therefore, is tied integrally to the study of men, but not women.37 Nonetheless, a social construction of masculinity in women can be traced back at least to the ancient Greeks.

Even the very category upon which the term masculinity rests, "men," has been perceived as socially constructed.38 This phenomenon can also be detected in Greek literature. When a Greek woman is called "masculine" [andreia] or an Amazon "equivalent to a man" [antianeira], we might say that there is still some distinction drawn between sex and gender; but when Antigone, Oedipus' daughter in Athenian tragedy, is called a "man," the binary distinction drawn between the sexes is destabilized (Hipp. On Reg. 1.29.1; Hom. IL 3.189, 6.186; Soph. Ant. 528, Oed. Col. 1368). If sex is to be read as a signifier in language, then it must signify something else besides biological difference when Oedipus refers to Antigone as a man.

When Creon, Antigone's tyrannical uncle, refers to her as a man, he marks her defiance against male authority, her refusal to be submissive (Soph. Ant. 528).39 In this context, Antigone is like an Amazon. In a different context, when Oedipus, Antigone's father, calls her a man because of her loyalty to himself, Antigone has risen above the expectations that men held for women (Soph. Oed. Col. 1559-63). Generally speaking, when women are equated with men or called masculine, they exhibit behavior or characteristics that, in a misogynistic milieu, were more expected of men. As I will demonstrate in Chapter 1, such behavior could be viewed both positively and negatively. In Attic tragedy, Antigone's "masculine" loyalty to her father is viewed favorably whereas the "manly" boldness of Clytemnestra, who kills her husband Agamemnon and usurps his power, is viewed unfavorably, despite the fact that she did so to avenge Agamemnon's sacrifice of their daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis.

Furthermore, an investigation of behavior perceived to be masculine in ancient Greek women reveals that variance from ancient Greek gender norms cannot be understood in the same way that gender-queerness is theorized today. There is a need to develop historical models to gauge gender variance in women, and such models, particularly with respect to the ancient Greeks, have been lacking. Generally speaking, theoretical models of gender

further

pages are missing.......................

Towards the end of this same epoch, the Hellenistic period, Egyptian soldiers proclaimed Arsinoe IV pharaoh of Egypt and ultimately commander of its armed forces. In both Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Syria, royal women found them-selves in positions of leadership, garnering a kind of power that would have never been available to women in Athens and Sparta. With that power came the responsibility to lead armies, to be a general. Women from Arsinoe II to Cleopatra VII displayed their courage and garnered power in the tumult of political turmoil. Ptolemaic queens such as Berenice II, Arsinoe III, and Cleopatra III rallied troops and led them to victory. These women and others exhibited the kind of bravery in both warfare and revenge that was limited to men in Athens.

Daniel Ogden has convincingly argued that "amphimetric strife" between contenders for the throne ultimately destabilized the Hellenistic kingdoms.185

The term amphimetor is defined by Hesychius (s.v. amphimetor) as "sharing the same father, but not the same mother."186 Ogden defines amphimetric strife as "disputes between the mother-and-children groups" who fought for Hellenistic thrones.187 Polygamy, Ogden asserts, lay at the root of amphi-metric, Hellenistic power struggles between the sons of different wives of the deceased king.188 In this chapter, I have expanded upon the idea of "amphi-metric strife" by identifying both Olympias and Adea Eurydice as participants in such conflict after Alexander's death.189 Furthermore, I have confirmed that not all royal rivalry can be reduced to a pattern of "amphimetric strife" alone. Full-sibling rivalry also played its role, as the histories of Ptolemy IX and Ptolemy X illustrate well. Powerful, courageous, warlike women, such as Cleopatra II and HI, were at the center of such strife. Cleopatra III led an army against one of her sons, Ptolemy IX, and defeated him (Josephus Al 13.13.1-2). Ptolemy IX engaged in what might be best called "metric" strife with his own mother, Cleopatra III, but he could not stop her from playing kingmaker: she put his brother, Ptolemy X, on the throne in his stead.

Berenice II is another example of a warrior queen who played "kingmaker." She succeeded in quelling rebellions and in wresting her dowry, the Cyrenaica, from Demetrius the Fair and handing it to Ptolemy III, a far better husband (and king). In the end, she ultimately failed in handing the throne to her son Magas, however, and paid the ultimate price, death, for favoring one son over another.

Whereas the circumstances of warrior queens and nomadic "Amazons" may have been different, they had one thing in common: a need to defend themselves from enemies. The same could be said for kings.

Civilized "Amazons": women bodyguards and hunters in ancient India and Persia :

Women bodyguards and hunters in ancient India and Persia :

Greeks who came into contact with the ancient courts of India and Persia commented not only on the seclusion of women in harems but also on yet another custom that would seem strange to Greek ears: female bodyguards and hunting companions of kings.' At the turn of the fourth to third century BCE, a Greek ambassador named Megasthenes was sent by Seleucus I Nicator to visit the court of his rival, the great Indian emperor Chandragupta Maurya.2 Megasthenes recorded what he saw in his Indica, preserved today only in fragments. In particular, he noted that the Indian monarch was surrounded by armed women who served as his intimate hunting companions:

The care of the king's body is committed to women who have been purchased from their fathers; outside the gates are male bodyguards and the remaining army. A woman who kills the drunken king holds a position of honor and consorts with his successor. Their children succeed him. The king does not sleep during the day, and at night he is forced to change beds periodically on account of the plots [against him] ...

A third [type of outing] is a Bacchic hunt, with a circle of women surrounding [the Icing], and outside of them a circle of [male] spear-bearers. The road is roped off and any man who passes inside to the women is killed. The drumbeaters and bell carriers advance [first]. The king hunts in enclosed areas shooting arrows.

Comparison of Megasthenes' text to Sanskrit treatises and literature, ancient Indian art/iconography, and a host of later documentation reveals that South Asian monarchs were indeed guarded by women from at least the Mauryan period until the nineteenth century. Likewise, Heracleides (FGrIlist 689 F 1; c.350 aa) relates that the Achaemenid Persian kings were also guarded by women "concu-bines."3 In both cultures, the women bodyguards also hunted with the king.

In this chapter, I will demonstrate that the custom of arming women as bodyguards and hunting companions was not limited to ancient India, but seems to have been a widespread Indo-Iranian practice." I will also argue that women bodyguards were imported from Central Asia, from the same places where Greek authors located Amazons and other warlike women. After a detailed investigation of the ancient evidence of Indian women bodyguards, I will turn to later descriptions of royal life in the Indian subcontinent. I will use this evidence to demonstrate the longevity of the custom of arming women as guards of South Asian kings and queens, and also to attempt to fill in the blanks of what we do not know about such customs in earlier times. Finally, I will analyze evidence from Achaemenid Persia, where the documentation is more fragmentary but nevertheless suggests customs similar to those found in ancient India.

Marvelous women in Megasthenes' Indica :

Megasthenes presents the oldest extant account of an Indian king's female bodyguards. Strabo (2.1.9=FGrHist 715 T 2c) tells us that Megasthenes was sent as an ambassador to the court of Sandrakottos at Palimbrotha.5 San-drakottos is a Greek variant of the Sanskrit Chandragupta, the powerful first Greek visiting India such as Megasthenes. Strabo tells us about the Sydracae who lived near the Indus river.

They were apparently thought to be the "descendants of Dionysus" by the Alexander historians, "judging from the vine in their country and from their costly processions, since the kings not only make their expeditions out of their country in Bacchic fashion, but also accompany all other processions with a beating of drums and with flowered robes, a custom which is also prevalent among the rest of the Indians" (Strabo 15.1.8). As I will discuss later in this chapter, the Indian king did model himself after gods. Royal expeditions were held with pomp.

The Roman-era author Quintus Curtius Rufus describes women accom-panying an unnamed Indian maharaja (a contemporary of Alexander the Great) hunting: "The hunt is [his] greatest exercise, in which he shoots shut-in animals in a preserve among the prayers and songs of his concubines" (8.9.28).13 We are left wondering if singing would attract or scare off prey, but in an enclosed hunting ground the animals did not stand much of a chance in either silence or song. Curtius used Megasthenes, but also had other sources!' Curtius' idea of a concubine may be flavored by his own cultural ideology of gender.

Megasthenes asserts that the king's women attendants were purchased from their fathers (FGrHist 715 F 32). This statement is compatible with the customs described in the Sanskrit Laws of Manu, wherein the groom pays a price to the bride's family for her hand (8.204, 366, 369; 9.93, 97, ed. Olivelle).15 Traffic in women also involved the purchase of girls to become servants, whose families would have most likely been compensated with the equivalent of a bride price. Additionally, the laws (7.125) prescribe that a king's minister should provide a living to the women employed in the king's service.16

Women guards in influential Sanskrit texts : from Kautilya's Arthshashtra to Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra and beyond :

Megasthenes' description of women bodyguards in the Indian court can be verified in ancient Sanskrit texts, including the Arthatastra of Kautilya and the Kama Stitra of Vitsyiyana. Kautilya's Arthafastra is a treatise on state man-agement. It is prescriptive in nature, although some aspects of it may be viewed as descriptive.17 Kautilya was familiar with the security system of monarchs contemporary to his time, and relates anecdotes of kings who were killed by their own wives or sons.

To protect the king from plots against his life, Kautilya prescribes that he be guarded "by women archers" [striganair dhanvibhily] at night. Kautilya describes an elaborate system of security, which is directly correlated to the king's reception in the morning: "Upon rising from bed, he should be sur-rounded by female attendants armed with bows [striganair dhanvibhih],in the second chamber by eunuch clothiers and hairdressers, in the third chamber by humpbacks, dwarves, and Kiratas, and in the fourth chamber by advisors, kinsmen, and doorkeepers armed with lances" (Arthatastra 1.21.1, ed. Kangle). Kautilya designates the task of guarding the king's body within his inner chambers to women, not eunuchs. Although the Sanskrit term labels the women as archers [dhanvibhih, instrumental plural of dhanvij, they probably had daggers or some other kind of close-range weapons as well.

One

of the extant Sanskrit manuscripts reads vandibhily or "bards,"

instead of dhanvibhih (1.21.1, ed. Kangle). This is probably a corruption,

but an interesting one. As mentioned above, women are noted as being

guards, bards, hunting companions, and concubines in Greek and Latin

texts describing India.

Traditionally, the Arthattistra has been dated to the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. If this date is correct, the text would be contemporary with Megasthenes. An Indian legend asserts that Kautilya was none other than the first minister of Chandragupta Maurya.19 Furthermore, the author signs each chapter "Kautilya," and ends the ArthaIastra with a pronouncement that he overthrew the Nanda dynasty. The last king of the Nanda dynasty was allegedly slain by Kautilya, who put Chandragupta Maurya on the throne. The Vishnupurana (4.24) confirms this story of Kautilya, who is also called Vishnugupta and Chanalcya.20

The dating of Kautilya is controversial, however; scholars have recently rejected the idea that the Arthakistra is a Mauryan text and instead date it to the early centuries of the Common Era.21 Passages containing information about foreign products, such as Alexandrian coral and Chi'n silk, have been used to argue against an earlier date.22 T. R. Trautmann has done extensive computer stylistic modeling on the Arthailistra and has concluded from the variety of Sanskrit "potential discriminators" (commonly used particles) that the text has more than one author.23 Further, he asserts, "The Arthakistra presumes the use of Sanskrit in royal edicts in any case, and Sanskrit inscrip-tions do not become general in northern India until the Gupta period" (4th-early 6th c. cs).24 At that time, the final text was perhaps recensed by one individual from earlier texts.25 Most texts were altered when copied over, up until the Gupta period, when standardization became more important.26 Thus the text contains information that post-dates the Mauryan era. Although the text as received is not contemporary to Megasthenes, the origin of its central ideology probably dates back to at least Mauryan times.27

In any event, women guards were part of an elaborate court system described by Kautilya, which provided the king with everything he might need from security to a top-end turban salon. There is no mention of eunuchs holding or using weapons in Kautilya. Instead, the eunuchs are described as kancuki-s and usnisi-s. Mitra translates these terms as "grooms" and "hairdressers," respectively. Likewise, Shamasastry renders these words as "presenter of the king's head-dress" and "presenter of the king's turban." A more literal rendering of the Sanskrit by Kangle describes the eunuchs "as wearing jackets and turbans? Although Kangle's translation is truer to the Sanskrit, the other translations of the text make more sense, given the context. The second chamber from the king's bedroom, the ctiatitharabhami, is de-scribed in Sanskrit texts as the place where the king was dressed and his turban fashioned.28 The king was richly groomed and jeweled by his eunuchs, and his adornment was ritualized.

Hence, eunuchs were not necessarily guards in ancient India. This may have been the case in Istanbul, but not in South Asia, where women were the intimate bodyguards of the king. In the third chamber, the king is surrounded by dwarves, humpbacks, and Kiratas, or "wild mountain men." It has been suggested that these characters would not have been attractive to the women of the palace, and hence made "safe" guards who would not father illegitimate children on the king's wives.29 Finally, the king is greeted in the fourth chamber by ministers, relatives, and "doorkeepers armed with lances." The spatial arrangements described by Kautilya are more elaborate than those of Megasthenes. Of interest, however, is that Megasthenes' sketch mirrors what Kautilya tells us: that women guarded the king in the inner environs of the palace, while male bodyguards/doorkeepers were stationed outside of the royal apartments. Comparison to later evidence suggests that there was a point in the royal apartments past which no man entered, not even eunuchs.30

Hence, women bodyguards were employed primarily to ward of other women attackers, although any kind of danger could lurk within the inner apartments. In tandem with Megasthenes, Kautilya (1.20, ed. Kangle) describes the danger presented by queens, princes, and other relatives. He writes:

When in the interior of the harem, the king shall see the queen only when her personal purity is vouchsafed by an old maid-servant. He shall not touch any woman (unless he is apprised of her personal purity); for hidden in the queen's chamber, his own brother killed Bhadrasena; hiding himself under the bed of his mother, the son murdered king Kara§a; mixing fried rice with poison, as though with honey, his own queen poisoned laiiraja; with an anklet painted with poison, his own queen killed Vairantya; with a gem of her zone bedaubed with poison, his own queen killed Souvira; with a looking-glass painted with poison, his own Kautilya advises that all packages coming and going in and out of the palace be thoroughly inspected, that no one inside the palace be allowed to establish contact with those outside, and that the inhabitants of the palace not be allowed to move freely. All of these security precautions were protections against plots designed to kill the king or overthrow him.

Queens represented danger, and caution was to be employed in their presence. Sons are described as equally untrustworthy, for princes could quickly rebel against or assassinate their fathers to secure the throne for themselves. The urgency of protection at home is stressed in a section of the Arthatastra entitled "Protection from princes": "A king can only protect his kingdom when he is protected from his own enemies, first and foremost from his own wives and sons" (1.17.1, ed. and trans. Kangle). Special attention needed to be paid toward princes, for they, "like crabs," had "a tendency of devouring their begetter" (1.17.5). It is advised that those sons who lack in filial affection be punished secretly (1.17.6).

An Indian king was unsafe even with his own wives and sons. Women guards were a necessary component of palace life.

Vatsyiyana, the author of the Kama Sutra, also describes women guarding the compartments of the royal queens and princesses. The Kama Sutra was probably written in the third century CE, but is a compilation of other, earlier works. Vatsrayana cites numerous ancient authors to legitimize his text (e.g. 1.5.22-5, ed. Dvidevi).32 Vatsydyana gives instructions for a male interloper to obtain access to the harem, even though he acknowledges that such behavior is dangerous and taboo. in so doing, he mentions the women in charge of the harem. Part of the process of obtaining illicit access to the harem involves befriending and tipping guards and others who worked in the female apart-ments: "They (interlopers] are assisted in their entrance and exits by the nurses and other harem women, who desire gifts" (Kama Sutra 5.6.7, ed. Dvidevi).33 The Jayamangala commentary on this passage, written around the twelfth century a by Yaiodhara, provides further description: "In order to be let in among the women of the harem and allowed out again, citizens distrib-ute tips to the women guarding the entrance, who thus derive a profit from their visits" (ed. Dvidevi).34 Vitsyiyana asserts that it is wrong for a citizen to enter the harem, even though he provides instructions on how to do so (5.6.6-48). Likewise, he establishes that guarding the harem was serious work not to be taken lightly, considering the penetrability of the inner chambers: "For these reasons a man should guard his own wives. Scholars say: `Guards stationed in the harem should be proved by the trial of desire.' Gonikaputra says Tut fear or power may make them let the women use another man; therefore guards should be proved pure by the trials of desire, fear, and power'" (Kama Sutra 5.6.39-42).35 Kautilya (1.10.1-20) describes various loyalty tests for ministers of the king and notes that bodyguards must also be tested.36

The Indian royal women's quarters, called the antahpura or strinivela in Sanskrit, was a homosocial institution where women were generally secluded from all men except their husband: For security reasons, no one may enter the inner apartments. There is only one husband, while the wives, who are often several, therefore remain unsatisfied. This is why, in practice, they have to obtain satisfaction among themselves. (Vitsyayana Kim Sutra 5.6.1)37

The Kama Sutra further suggests women servants took on a masculine role in sex with the secluded wives:

The nurse's daughter, female companions, and slaves, dressed as men, take the men's place and use carrots, fruits, and other objects to satisfy their desire. (5.6.2)38

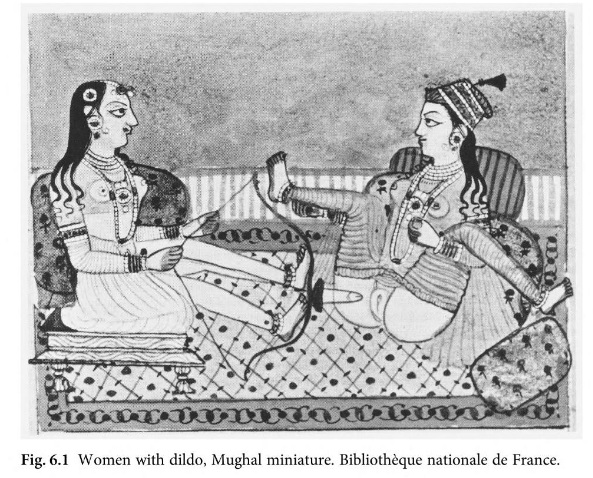

Additionally, "virile behavior in women" (purusayita) is also discussed and prescribed by the Kama Sutra (2.8), the Jayamatigala commentary on the Kama Sutra (2.8), and the approximately twelfth-century CE Ratirahasya of Kokkoka, more popularly known as the Kokaiastra (9). In the Mughal period, a seventeenth-century Persian translation of the Sanskrit Kokalastra was illus-trated with a painting of a woman holding a bow and arrow (see Fig. 6.1). At the tip of the arrow, a dildo is poised to be inserted into another woman. Unfortu-nately, this manuscript is now lost at the Bibliotheque nationale de France, and the exact context of the illustration, photographed years ago, is not known.39

This scene may have illustrated the Purustlyita ("Virile behavior in women") chapter of the Persian translation of the Kokagastra—this would be the most fitting location for it. The earlier Sanskrit version of the Kokalastra, the Ratir-ahasya, is extant and does contain a chapter entitled Purusayita (9). Alex Comfort interprets purusayita in the Kokakistra as the woman sitting on top of a man, in the same manner that Burton's Victorian English translation of the earlier Kama Sutra explains this behavior.40 There is a problematic issue of agency with Burton's Victorian English rendition.41 A literal translation of the Sanskrit reveals that purusayita in the Kama Sutra refers to the use of an artifical phallus, with a woman taking an active role in sex with both males and females.42 The intensity of the sexual act illustrated here is mirrored in various descriptions of purufayita in the Kama Sutra (2.8.25), particularly a practice called "The Cruel" in which the dildo is "brutally driven in" and "pressed forcefully" in and out for a long period of time.

The woman shown in the illustration would appear to be a female guard given her attributes of bow and arrow. She is dressed differently than her more feminine counterpart. As such, she may be the type of servant that Vatsyayana mentions as servicing women while dressed as a man. In the Indian court, we see variation in female masculinities—some women guards were potentially conceived of as "masculine" due to their fighting abilities, others due to their sexual inclinations, which could be used to satisfy queens or other harem women. Some women might have been perceived as masculine for both of these reasons, or have slipped from one category to another. As Halberstam argues for the modern West, the material surveyed for precolonial India calls for us "to think in fractal terms about gender geometries," and to "consider the various categories of sexual variation for women as separate and distinct from the modern category of lesbian.43

The woman guard illustrated in the Persian Kokalastra might also be labeled a "stone butch" who, "in her self-definition as a non-feminine, sexually untouchable female, complicates the idea that lesbians share female sexual practices or women share female sexual desires or even that masculine women share a sense of what animates their particular inasculinities.44 The main complication with such a reading of the image, however, is that which plagues all of the various female masculinities discussed in this book. As Spivak argues for modem Indian women, these women are subaltern and hence muted. The literary and artistic representations of them, although made by male authors, nonetheless suggests a different sexual climate in premodem India than that of the modem West. Whereas our society is "committed to maintain-ing a binary gender system. 45 (even if such a system is ultimately challenged again and again), what we see in precolonial India suggests more fluidity.

Halberstam notes that "few popular renditions of female masculinity under-stand the masculine woman as a historical fixture who has challenged gender systems for at least two centuries."46 I have demonstrated that female mascu-linity has existed for more than two millennia. In the ca. 1st century CE Carakasarnhita (4.2.19, ed. Acharya) and Suirulasarphita (3.2.43, ed. Acharya and Acharya) Sanskrit medical texts, the narisandha [masculine lesbian] is described as the product of either the mother taking an active, masculine role during procreation, or of embryonic damage. Sweet and Zwilling note that, like the Western Amazon, the masculine lesbian is further described as "breastless" [astani] and "man-hating" [rydvesini] (Caraka sarphitti 6.30.34).

Women

bodyguards, goddesses of dawn : The Buddhist companions of the Sun

God Surya :

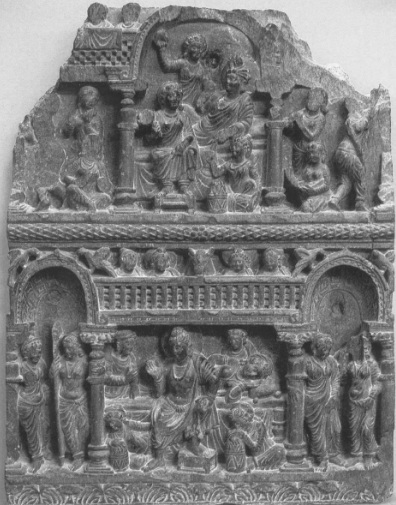

Fig. 6.4 Siddhartha's renunciation. Courtesy of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan Native versus Yavani :

A Kushan-era statue from Gandhara may also represent a female guard, who is dressed in native Indian (as opposed to Greek) dress and is armed with both a spear and a shield (see Fig. 6.5).75 The statue has been dated to the period of Kushan rule, sometime after 60 CE but before c.110 CE. Like other representations of female guards, the woman holds a spear. The shield she holds is more unusual, and perhaps shows some influence coming from Bactria or another region of Central Asia.76 This natively clad female warrior can be instructively compared to another statue from the Gandhara region, thought to be either a yavani [foreign/Ionian/Greek] female guard or a representation of a warlike goddess, either Athena or Roma (see Fig. 6.6).77

The Greek chiton and helmet are directly telling of the Hellenistic influence found at Gandhara.78 Her left arm is broken off, but it is thought that she once held a spear.79 The way in which the remaining arm is raised is suggestive of this. The piece dates to c.50-150 CE.80 Although the helmet is considered by Ingholt to be an attribute of a warrior goddess, Block argues that the sculpture represents a female guard or yavani.81

The term yavani refers to a stock character in Sanskrit drama who was a palace attendant, not only assisting the king with weapons but also hunting with hint In Kalidasa's sakuntula (c.4th-5th c. CE), a woman called a yavani attends the king by carrying his bow and arrow so that he may reach for it at attends the king by carrying his bow and arrow so that he may reach for it at any time (act 2, prelude, act 6) and in another drama, also by Kalidasa, the Vikramorvafiyam (act 5) a yavani brings the king's bow to him.82 The Sanskrit term yavani is a feminine variant of yavana or yona [Ionian or Greek], but may actually refer to women of both Greek and other origins. "The term Yavana [Greek] was gradually extended to include not only the local Greeks, but any group coming from west Asia or the eastern Mediterranean. Much the same was to happen to the term saka-s with reference to central Asia, but

Refrences of The Amazons , Orientalism and Amazons, Orientalism and Matriarchy and Female Masculinity :

1 The ideology of male superiority is, ultimately, ideology, "not statement of fact." Sarah B. Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity, 2nd edn (New York: Schocken Books, 1995), 97. On the contradiction between Greek gender ideology and "some Greek narratives," see also Stella Georgoudi, "To act, not submit: women's attitudes in situations of war in ancient Greece," in Jacqueline Fabre-Serris and Alison Keith (eds), Women and War in Antiquity (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), esp. 203-4.

2 See e.g. Fritz Graf, "Women, war, and warlike divinities," ZPE 55 (1984), 245-54; Jean Ducat, "La femme de Sparte et le guerre," Pallas 51 (1999), 159-71; Pasi Loman, "No woman no war: women's participation in ancient Greek warfare," Greece Rome 51(1) (2004), esp. 36-8; Mauro Moggi, "Marpessa detta Choira e Ares Gynaikothoinas," in Erik fostby (ed.), Ancient Arcadia: Papers from the Third International Seminar on Ancient Arcadia (Athens: Norwegian Institute at Athens, 2005), 139-50.

3 Themiscyra was situated near the mouth of the Thermodon river on the south shore of the Black Sea near modern Terme, Turkey.

4 Isocrates (12.193) says that Hippolyte was the Amazon who fell in love with Theseus, not Antiope (Hippolyte and Antiope seem to be interchanged as the Amazon turned wife of Theseus). See further It L. Fowler, Early Greek Mythography, vol. 2: Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 486; Adrienne Mayor, The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 259-70.

5 The 9th-c. CE scholiast Theognotus, who writes "as in Callimachus, 'where the Amazon men are'," suggests that some authors may have included men among the Amazons. Callimachus, Fragmenta (incertae sedis) no. 721 (although elsewhere Callimachus uses the term Amazonides, modified by the adjective epithumetherai, to obviously refer to a group of women only (Hymn to Diana 237). Extant texts (e.g. Diodorus 2.45, 3.53) suggest that if males were thought to be part of an "Amazon tribe" by Greeks, they were seen as submissive to the women.

6 On 18th-c. and 19th-c. attempts to find an "historical core" of the Amazon myth, see Josine H. Blok, The Early Amazons: Modern and Ancient Perspectives on a Persistent Myth, trans. Peter Mason (New York: E. J. Brill, 1995), esp. 21-143.

7 Although I made this comparison independently in a paper entitled "Female masculinity plus: iron, Amazons, and Scythians" presented at the Jan. 2014 American Historical Association Conference, Adrienne Mayor, in a book published in Sept. 2014, also notes the similarities in the Amazon and Scythian conquests. The Amazons, 269.

8 According to Mayor, "Amazons were Scythian women" (ibid., 12).

9 Hellanicus (FGrHist 4 F 107) tells us that the Amazons cauterized their breasts, whereas Hippocrates (Airs 17) tells us that the Sauromatian women did so. Diodorus (2.45, 3.53) calls the Amazon ethnos gunaikokratoumenon "ruled by women," whereas Ephorus (FGrHist 70 F 160) calls the Sauromatians gunaikokratoumenoi.

10 H. A. Shapiro, "Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians," GRBS 24 (1983), esp. 105-10; Blok, The Early Amazons, 148, 216-17; Mayor, The Amazons, 96-8.

11 See "Epic Amazons and Thracians" in Ch. 3.

12 On the usage of the term "Amazons" by archaeologists to simply mean warrior women, see Askold Ivantchik, "Amazonen, Skythen und Sauromaten: Alte unde moderne Mythen," in Charlotte Schubert and Alexander Weiss (eds), Amazonen zwischen Griechen und Skythen: Gegenbilder in Mythos und Geschichte (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2013), 73. Recent literature on this subject, and the debates entailed therein, is discussed in "Archaeological evidence: Scythians, Sauromatians, Thracians, and 'Amazons" in Ch. 2. Recent overviews of the evidence are provided in English by K. Linduff and K S. Rubinson (eds), Are All Warriors Male? Gender Roles on the Ancient Eurasian Steppe (Lanham, Md.: AltaMira Press, 2008) and Mayor, The Amazons, 64-83, as well as in German in the catalog Amazonen Geheimnisvolle Kriegerinnen (Munich: Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer, Minerva, 2010).

13 Graves of warrior women in the Caucasus pre-date any known representation of an Amazon in Greek art or literature by more than a century. See "Amazons in Colchis" in Ch. 3. Cf. Askold lvantchik, "Amazonen, Skythen und Sauromaten: alte und modern Mythen," in Charlotte Schubert and Alexander Weiss (eds), Amazonen zwischen Griechen und Skythen: Gegenbilder in Mythos und Geschichte (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2013), 73-87.

14 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York Vintage Books, 1979), 1.

15 Ibid., 5. 16 Ibid., 4. 17 E.g. Pithekoussai, Emporiai, Naucratis.

18 S On the dichotomy between masculine Greeks and effeminate barbarians in Greek litera-ture, see Edith Hall, Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989); Page duBois, Centaurs and Amazons: Women and the Pre-history of the Great Chain of Being (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1982), esp. 4, 86.

19 Theories of the "other" do not stem directly from postcolonial theory, but have rather been appropriated from or at least have a relationship to the 20th-c. "French school" of thought. See further Beth Cohen, Introduction to Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art (Leiden: B. J. Brit 2000), 6-8. Said nevertheless "popularized the dialogue of the other in America," according to Beth Cohen, "and called specific attention to fifth-century B.C. Greece, and Classical Athens in particular, as having first articulated the 'us' versus 'them' opposition of the West and the Orient." Cohen, Introduction, 8.

20 See further Dennis Porter, "Orientalism and its problems," in The Politics of Theory: Proceedings of the Essex Conference of the Sociology of Literature, July 1982 (Colchester: Univer-sity of Essex, 1983), esp. 181-2; Robert J. C. Young, Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 389-92.

21

See further Peter Stewart, review of Beth Cohen (ed.), Not the Classical

Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, BMCR

(2000.01.08), bmcr.brynmawr.edu/ 2001/2001-01-08.html, retrieved

May 26, 2014; Erich Gruen, Rethinking the Other in Antiquity (Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), esp. 1-5; Mac Sweeney, Foundation

Myths and Politics in Ancient Ionia (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2013), esp. 1-6, 129, 152-5, 198-203.

23 See e.g. Shelby Brown, ' ' 'Ways Of seeing' women in antiquity. an introduction to feminism in classical antiquity and ancient art history," in Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Claire Lyons (eds), Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality, and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology (London: Routledge, 1997), 12—42; Irad Malkin, Returns of Odysseus: Colonization and Ethnicity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), esp. 17—18; Cohen, Not the Classical Ideal, 11; Irad Malkin, "Postcolonial concepts and ancient Greek colonization," Modern Language Quar- teriy 65(3) (Sept. 2004), 341-64; Gruen, Rethinking the Other in Antiquity.

24 On the cultural differences among the Greeks, see Carol Dougherty and Leslie Kurke, "Introduction: the cultures within Greek culture," in Dougherty and Kurke (eds), The Cultures Within Greek Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), esp. 1—2, 6—13; Carla Antonaccio, "Hybridity and the cultures with Greek culture," in the same volume, 57-74; Malkin, "Postcolonial concepts," 346.

25 Malkin, ibid., 343—6, discusses both the tendency Of Greeks to engage in binary thought and the plurality of difference among the Greeks themselves.

26 Lebedynsky suggests that the legend Ofthe Amamns may have been inspired by Greek contact With the Cimmerians, yet another people of the Eurasian steppes, around 640 NC". The Amazons are associated with the Cimmerians in a late source, OrosiLLs (Adversus paganos historrarum I _21-2), but there is no archaeological data to prove the existence of warrior women among the Cimmerians at this time. laroslav Lebedyn sky, Les A mazones: mythe et réalrté desfemmes guerriéres chez les anciens nomades de steppe (Paris: Errance, 2009), 13—14.

27 See the summary of scholarship on Amazons provided in Ch. 2.

28 Otto Brendel, personal communication to Larissa Bonfante. Larissa Bonfante, "Classical and barbarian," in Bonfante (ed.), The Barbarians of Ancient Europe: Realities and Interactions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 201 1), 7, 25 n. 16.

29 Robert Dale parker, Introduction to Critical Theory: A Reader for Literary and Cultural Studies (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 3.

30 E.g. Makin, "Postcolonial concepts"; Tamar Hodos, Local Responses to Colonization in the Iron Age Mediterranean (London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2006), esp. 11-12

31 Tamar Hodos, "Local and global perspectives in the study of social and cultural identities," in Shelley Hales and Tamar Hodos (eds), Material Culture and Social Identities in the Ancient World (Cambridge. Cambridge University Press, 2010), 9, 23.

32 William Blake Tyrrell, Amazons: A Study in Athenian Mythmaking (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984); Blok, Early Amazons, 133-4.

33 Susan Deacy, "Athena and the Amazons: mortal and immortal femininity in Greek myth," in Alan B. Lloyd (ed.), What is a God? Studies in the Nature of Greek Divinity (London: Duckworth/Classical Press of Wales, 1997), 154-5.

34 "Female masculinity" is a term used by Judith Halberstam to refer to the modern history and culture of "women who feel themselves to be more masculine than feminine." Female Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), xi.

35 See Chs 1 and 4.

36 Serena Nanda, Gender Diversity: Crosscultural Variations (Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press, 2000), 7, citing Vern L. Bullough and Bonnie Bullough, Cross Dressing, Sex, and Gender (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993), 46. See also Julia Serano, The Whipping Girl: A Transsexual on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (Emeryville, Calif.: Seal Press, 2007), esp. 5. 37 See further Halberstam, Female Masculinity, esp. 1-9,13-15.

38 Judith Butler asserts that "[w]hen the constructed status of gender is theorized as radically independent of sex, gender itself becomes a free-floating artifice, with the consequence that man and masculine might just as easily signify a female body as a male one, and woman and feminine a male body as easily as a female one." Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (repr. with new preface, New York Routledge, 1999), 10.

39 See "Female masculinity, defiance, and loyalty: Electra and Antigone" in Ch. 1.

deviance as developed in the field of queer theory have tended to be ahistorical, tied closely to modern, Western notions of gender dichotomy.40 There is a strong historical component to gender, however, and the historian of gender must account not just for linear change but also for numerous other factors, including race, ethnicity, and class.41

Thus, we must recognize that women who would have seemed "masculine" to Athenians or other Greeks may not have seemed so to the locals among whom they lived or over whom they ruled. Gender roles are constituted uniquely in different contexts and periods, through a repeated performance that "is at once a reenactment and reexperiencing of a set of meanings already socially established.42 Such a set of meanings is not constituted in the same manner at all times, but changes as societies evolve, and varies among different societies existing at the same time. Whereas the Athenians conceived of masculine behavior and masculinity in women, their assessments were pro-duced and reiterated in a society where strong binary oppositions were drawn between men and women. This does not appear to have been the case within some non-Greek and even some mixed Greek/barbarian societies. The day-to-day needs of nomadic life fostered less of a gendered division of labor than in Athens, and monarchical or tyrannical governments in other Greek-ruled locations allowed elite women to hold power that would have been impossible for women to attain at Athens.

Halberstam argues that "the challenge for new queer history has been, and remains, to produce methodologies sensitive to historical change but influ-enced by current theoretical preoccupations."43 The commonly held mod-ern assumption that female masculinities "simply represent early forms of lesbianism denies them their historical specificity and covers over the multiple differences between earlier forms of same-sex desire. Such a pre-sumption also funnels female masculinity neatly into models of sexual deviance rather than accounting for meanings of early female masculinity within the history of gender definition and gender relations."44 There are many female masculinities,45 and those which we can recover from classical.

40 See Halberstam, Female Masculinity, 46. It is generally preferable to speak of gender "variance" as opposed to "deviance," but when one is historicizing, deviance may better encap-sulate the zeitgeist.

41 According to Butler, "gender is not always constituted coherently or consistently in different historical contexts... gender intersects with racial, class, ethnic, sexual, and regional modalities of discursively constituted identities. As a result, it becomes impossible to separate out `gender' from the political and cultural intersections in which it is invariably produced and maintained." Gender Trouble, 6. See also Sarah B. Pomeroy, Spartan Women (New York Oxford University Press, 2002), 131.

42 Butler, Gender Trouble, 178.

43 Halberstam, Female Masculinity, 45. " Ibid.

45 Ibid., 46, 57-9; See also Sheila Deasey, "After Halberstam: subversion, female masculinity, and the subject of heterosexuality" (Ph.D, University of Salford, 2010).

185 Ogden, Polygamy.

186 See A. H. Sommerstein, "Amphimitores," CQ 37 (1987), 498-500.

187 Ogden, Polygamy, X.

188 Ibid., esp. ix-xxv.

189 While Ogden mentions both Olympias and Adea Eurydice, he does not discuss their direct rivalry with one another in detail, but rather focuses on Olympias' hatred of Arrhidaeus. Ibid., 25.

Refrences of Women bodyguards and hunters in ancient India and Persia, Marvelous women in Megasthenes' Indica, Women guards in influential Sanskrit texts : from Kautilya's Arthshashtra to Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra and beyond, Women bodyguards, goddesses of dawn : The Buddhist companions of the Sun God Surya and Native versus Yavani :

1. Herodotus (3.69) comments on the seclusion of Persian royal women under a particular regime. Just how shut-in Persian women were in general is not entirely clear. See further Maria Brosius, Women in Ancient Persia 559-331 sc (New York Oxford University Press, 1996), 83-93. When citing Megasthenes, Strabo (15.1.56) notes that the customs of the Indians described by Megasthenes would seem nethia [strange] to his audience.

2 See further Hartmut Scharfe, "The Maurya dynasty and the Seleucids," Zeitschrift far Vergleichende Sprachforschung 85(2) (1971), 216-17. Klaus Kartunnen suggests that Mega-sthenes may have been sent by Sibyrtius, the satrap of Arachosia, where Arrian (5.6.2) and Curtius (9.10.20) tell us that Megasthenes lived. Klaus Karttunen, India and the Hellenistic World (Helsinki: Finnish Oriental Society, 1997), 70.

From a platform (two or three armed women stand beside him), and he also hunts in open hunting grounds from an elephant; the women [also) hunt, some from chariots, some on horses, and some on elephants and, as when they join a military expedition, they practice with all types of arms. (FGrHist 715 F 32)

3 Date derived from OCIY, 686.

4 Royal women bodyguards can be identified in Chinese and Thai courts of the 19th c. as well. See further Guy Cadogan Rothery, The Amazons in Antiquity and Modern Times (London: Francis Griffiths, 1910). 83-4. Women buried with weapons have been identified in the graves of ancient Cambodia (lst-5th c. a). Noel Hidalgo Tan, "'Warrior women' unearthed in Cambo-dia" (Yahoo News, Nov. 15, 2007), southeastasianarchaeology.com/2007/11/15/war-rior-women-unearthed-in-cambodia, retrieved Apr. 15, 2015. Further investigation of this phenomenon in Fast Asian history could be fruitful.

5 Little is known about the life of Megasthenes. It has been assumed on the basis of his name that he was of Greek origin. Arrian (5.6.2) mentions his subordination to the Seleucid satrap of Arachosia, Sibyrtius. Arachosia bordered on Mauryan dominions. See further Karttunen, India and the Hellenistic World, 70-1.

13 The exact date of Curtius' composition of the Histories of Alexander is unknown, but it is certain that he composed them after the reign of the first emperor, Augustus. J. E. Atkinson assigns a terminus post quem of 14 a and a terminus ante quem of 22617 CE for Curtius' writings. Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus' Historiae Alexandra Magni Books 3 and 4 (Amster-dam: J. C. Gieben, 1980), 19-23. 14 Karttunen, India and the Hellenistic World, 73-4.

I5 Although the treatise of Manu at one point decries the taking of a bride price as loathsome and tantamount to selling a daughter into prostitution (3.51-4; 9.98-100), it also provides clear guidelines for the taking of a bride price. In general, the laws attributed to Manu are full of such contradictions, perhaps because they represent a compilation of varying traditions. Wendy Doniger with Brian K. Smith, introduction to The Laws of Manic With an Introduction and Notes (London: Penguin Books, 1991), xliv-Iii.

16 The Laws of Manu is a compendium of Hindu thought that was a principal text of the religion by at least the early centuries of the common era. See further Doniger and Smith, intro. to The Laws of Mona, xvii. ]

17 Kumkum Roy, "The king's household: structure and space in the Sistric tradition," in Kunikum Sangari and Uma Chakravarti (eds), From Myths to Markets: Essays on Gender (New Delhi: Manohar, 2001), 20.

18 See 'Female guards, hunting companions, and concubines in Achaemenid Persia" in this chapter.

19 See further S. R. Goyal, Kautilya and Megasthenes (New Delhi: Kusumanjali Prakashan, 1985), esp. 1-4.

20 Preface to It Shamasastry, Kautilya's Arthaiastra (Mysore: Mysore Printing & Publishing House, 1915), esp. vii-ix; d T. Burrow “CaMakya and Kautilya; Annals of the Bhandakar Oriental Research Institute 47-9 (1968), 17-31. Burrow argues that Kautalya (a variant spelling of Kautilya) and Canakya should be distinguished.

21 Karttunen, India in Early Greek Literature, 146-7; India and the Hellenistic World, 13; Goyal, Kautilya and Megasthenes: A. A. Vigasin and A. M. Samozvantsev, Society, State, and Law in Ancient India (New Delhi: Sterling, 1985), 1-27; R. P. Kangle, The Kautiliya Arthatastra, pt 3: A Study (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1986), 59-115.

22 Karttunen, India in Early Greek Literature, 146-7; India and the Hellenistic World, 13; Romila Thapar, Atoka and the Decline of the Mauryas: With a New Afterword, Bibliography and Index, rev. edn (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997).

23 Thomas R. Trautman, Kautilya and the Arthaiastra: A Statistical Investigation of the Authorship and Evolution of the Text (Leiden: E. ). Brill, 1971), esp. 83-130,186-7. See also Thapar, Atoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, 292-3.

24 Trauttnann, Kautfiya and the Arthedastm, 5, citing 0. Stein, "Versuch einer Analyse des lasanadhikara," Zeitschrift fiir Indologie and Iranistik 6 (1928), 45-71.

25 Trautmann, Kautilya and the Arthaastra, 186-7. On the dates of the Gupta period, see Thapar, Early India, xiii-xv, 280-7.

26 See Thapar, Atoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, 294-5.

27 Ibid., 218-25.

28 Ali, Courtly Culture, 166.

29 Mid. Dwarves, like women bodyguards, are shown in the company of the god Surya on a relief from Niyamatpur. Two "female figures on either side" shooting arrows are among the "essential features of the common variety of North Indian Sun icons." Jitendra Nath Banerjea, "Surya," JISOA 16 (1948), 62-3. See "Women bodyguards, goddesses of dawn: the Buddhist companions of the sun god Surya" in this chapter.

30 See "Domingo Paes in south India' in this chapter.

31 Queen killed Jalutha; and with a weapon hidden under her tuft of hair, his own queen slew Viduratha.

31 ' Based upon the translation of Kangle.

32 On the date of the Kanto Sutra, see Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar, introduction to Kama Sutra: A New Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), xi.

33 Based upon the translation by Alain Danielou, found in The Complete Kama Satra, 378.

34 Ibid.

35 Based upon the translation of Doniger and Kakar.

36 See further Doniger and Kakar, Kama Sutra, 205-6, note on 5.6.41.

37 Based upon the translation of Danielou.

38 Translation Danielou.

39 Image derived from James Saslow, Pictures and Passions: A History of Homosexuality in the Visual Arts (New York: Viking Press, 1999), 125. I am grateful to Dr Saslow for his explanation of the history of this illustration and the lost manuscript, as well as to the staff of the Bibliotheque nationale de France, Departement des manuscrits orientaux, for their assistance in this matter. The manuscript has been missing since 1984.

40 Kokkoka, 77w Illustrated Koka Shastra: being the Retirahasya of Kokkoka and other Medieval Writings on Love, trans. Alex Comfort, preface by W. G. Archer, 2nd edn (London: Mitchell Reazley, 1997), 101.

41 Ruth Vanita, "Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra," in Vanita and Saleem Kidwai (eds), Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000), 48-50.

42 The layamaigala commentary reinforces this reading, and also prescribes the use of the hand for the masculine woman, the svairini, to penetrate the other woman (2.9.19).

43 Judith Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), 21, 57. 44 Ibid., 21. 45 aid., 27. 46 Ibid., 45.

74 Karetzky, The Life of the Buddha, second page of intro.

75 The piece is now housed in the Peshawar Museum, but its exact provenance is not known. Sir John Marshall, The Buddhist Art of Gandhara: The Story of the Early School, Its Birth, Growth, and Decline (Cambridge: University Press for Dept. of Archaeology in Pakistan, 1960), 40, 47, pl. 41, fig. 64.

76 Ibid., 40-47.

77 Ingholt, Gandluiran Art in Pakistan, 168-9, pl. 443.

78 Western influence in Gandharan art is variously interpreted as directly Greek, Hellenistic via Bactria, or Roman. See further Shashi Asthana with Bhogendra Jha, Gandluira Sculptures of Bharat Kala Bhavan (Varanasi: Bharat Kala Bhavan, Banaras Hindu University, 1999), 1-5; Ingholt, Gandharan Art in Pakistan, 168-9.

79 Ibid., 168.

80 Benjamin Rowland, Jr, "A revised chronology of Gandharan sculpture," Art Bulletin 18 (1936), 392 n. 24.

81 Ingholt, Gandharan Art in Pakistan, 168-9, no. 443; T. Block. A List of the Photographic Negatives of Indian Antiquities in the Collection of the Indian Museum (Calcutta: Government Printing, 1900). 50, no. 1195.

82 Karttunen, India and the Hellenistic World, 91, no. 108. |