| ACHAEMENID EMPIRE

Standard of Cyrus the Great

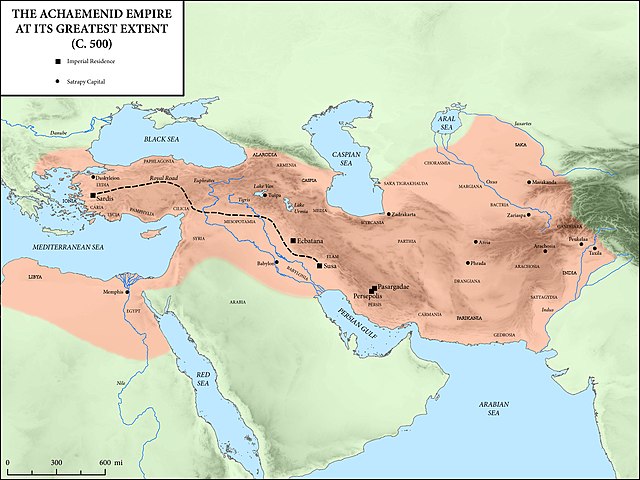

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius I (522 BC to 486 BC) Achaemenid Empire

Xšaça

550 BC - 330 BC

Capital : Babylon (main Capital), Pasargadae, Ecbatana, Susa, Persepolis

Common languages : Old Persian (official), Aramaic (official, lingua franca), Babylonian, Median, Greek, Elamite, Sumerian, Egyptian and Many others

Religion : Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, Babylonian religion

Government : Monarchy

King or King of Kings

• 559 - 529 BC : Cyrus the Great

• 336 - 330 BC : Darius III

Historical era : Classical antiquity

• Persian Revolt : 550 BC

• Conquest of Lydia : 547 BC

• Conquest of Babylon : 539 BC

• Conquest of Egypt : 525 BC

• Greco-Persian Wars : 499 - 449 BC

• Corinthian War : 395 - 387 BC

• Second conquest of Egypt : 343 BC

• Fall to Macedonia : 330 BC

Area

500 BC : 5,500,000 km2 (2,100,000 sq mi)

Population

500 BC : 17 million to 35 million

Currency : Daric, siglos

Preceded by

Median Empire

Neo-Babylonian Empire

Lydia

Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt

Gandhar

Sogdia

Massagetae

Succeeded by

Empire of Alexander the Great

Twenty-eighth Dynasty of Egypt

The Achaemenid Empire (romanized: Xšaça, lit. 'The Empire'), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire based in Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great. Ranging at its greatest extent from the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper in the west to the Indus Valley in the east, it was larger than any previous empire in history, spanning 5.5 million square kilometers (2.1 million square miles). It is notable for its successful model of a centralised, bureaucratic administration (through satraps under the King of Kings), for its multicultural policy, for building infrastructure such as road systems and a postal system, the use of an official language across its territories, and the development of civil services and a large professional army. The empire's successes inspired similar systems in later empires.

By the 7th century BC, the Persians had settled in the south-western portion of the Iranian Plateau in the region of Persis, which came to be their heartland. From this region, Cyrus the Great advanced to defeat the Medes, Lydia, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, establishing the Achaemenid Empire. Alexander the Great, an avid admirer of Cyrus the Great, conquered most of the empire by 330 BC. Upon Alexander's death, most of the empire's former territory fell under the rule of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire, in addition to other minor territories which gained independence at that time. The Iranian elites of the central plateau reclaimed power by the second century BC under the Parthian Empire.

The Achaemenid Empire is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city-states during the Greco-Persian Wars and for the emancipation of the Jewish exiles in Babylon. The historical mark of the empire went far beyond its territorial and military influences and included cultural, social, technological and religious influences as well. For example, many Athenians adopted Achaemenid customs in their daily lives in a reciprocal cultural exchange, some being employed by or allied to the Persian kings. The impact of Cyrus's edict is mentioned in Judeo-Christian texts, and the empire was instrumental in the spread of Zoroastrianism as far east as China. The empire also set the tone for the politics, heritage and history of Iran (also known as Persia).

Name

:

The Persian term Xšaça, meaning "The Empire", was used by the Achaemenids to refer to their multinational state.

History :

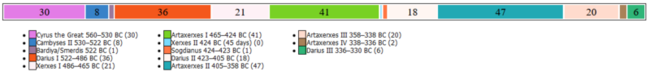

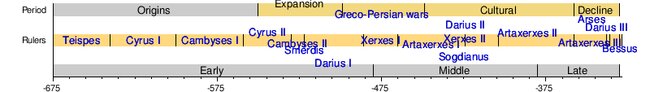

Achaemenid timeline :

Origin

:

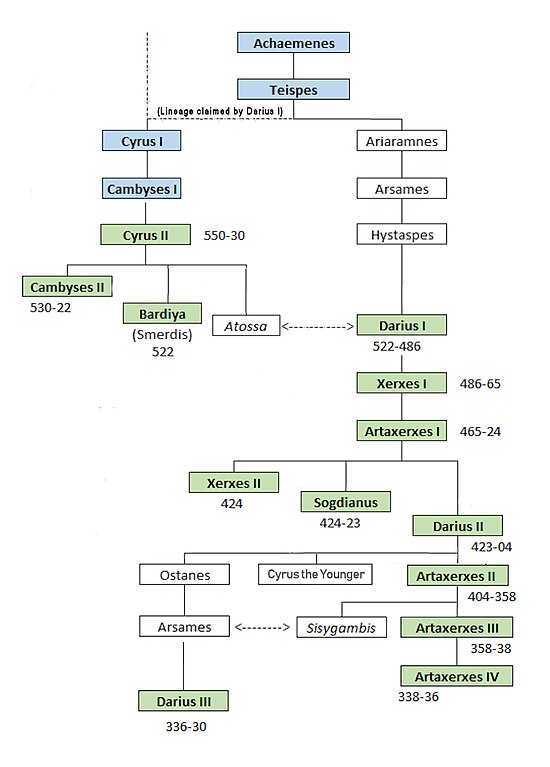

— Herodotus, Histories 1.101 & 125

Family tree of the Achaemenid rulers The Achaemenid Empire was created by nomadic Persians. The name "Persia" is a Greek and Latin pronunciation of the native word referring to the country of the people originating from Persis (Old Persian: Parsa). The Persians were an Iranian people who arrived in what is today Iran c. 1000 BC and settled a region including north-western Iran, the Zagros Mountains and Persis alongside the native Elamites. For a number of centuries they fell under the domination of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC), based in northern Mesopotamia. [citation needed] The Persians were originally nomadic pastoralists in the western Iranian Plateau and by 850 BC were calling themselves the Parsa and their constantly shifting territory Parsua, for the most part localized around Persis. The Achaemenid Empire was not the first Iranian empire, as the Medes, another group of Iranian peoples, established a short-lived empire and played a major role in the overthrow of the Assyrians.

The Achaemenids were initially rulers of the Elamite city of Anshan near the modern city of Marvdasht; the title "King of Anshan" was an adaptation of the earlier Elamite title "King of Susa and Anshan". There are conflicting accounts of the identities of the earliest Kings of Anshan. According to the Cyrus Cylinder (the oldest extant genealogy of the Achaemenids) the kings of Anshan were Teispes, Cyrus I, Cambyses I and Cyrus II, also known as Cyrus the Great, who created the empire (the later Behistun Inscription, written by Darius the Great, claims that Teispes was the son of Achaemenes and that Darius is also descended from Teispes through a different line, but no earlier texts mention Achaemenes). In Herodotus' Histories, he writes that Cyrus the Great was the son of Cambyses I and Mandane of Media, the daughter of Astyages, the king of the Median Empire.

Formation and expansion :

Map of the expansion process of Achaemenid territories Cyrus revolted against the Median Empire in 553 BC, and in 550 BC succeeded in defeating the Medes, capturing Astyages and taking the Median capital city of Ecbatana. Once in control of Ecbatana, Cyrus styled himself as the successor to Astyages and assumed control of the entire empire. By inheriting Astyages' empire, he also inherited the territorial conflicts the Medes had with both Lydia and the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

King Croesus of Lydia sought to take advantage of the new international situation by advancing into what had previously been Median territory in Asia Minor. Cyrus led a counterattack which not only fought off Croesus' armies, but also led to the capture of Sardis and the fall of the Lydian Kingdom in 546 BC. Cyrus placed Pactyes in charge of collecting tribute in Lydia and left, but once Cyrus had left Pactyes instigated a rebellion against Cyrus. Cyrus sent the Median general Mazares to deal with the rebellion, and Pactyes was captured. Mazares, and after his death Harpagus, set about reducing all the cities which had taken part in the rebellion. The subjugation of Lydia took about four years in total.

When power in Ecbatana changed hands from the Medes to the Persians, many tributaries to the Median Empire believed their situation had changed and revolted against Cyrus. This forced Cyrus to fight wars against Bactria and the nomadic Saka in Central Asia. During these wars, Cyrus established several garrison towns in Central Asia, including the Cyropolis.

Cyrus the Great is said in the Bible to have liberated the Hebrew captives in Babylon to resettle and rebuild Jerusalem, earning him an honored place in Judaism Nothing is known of Persian-Babylonian relations between 547 BC and 539 BC, but it is likely that there were hostilities between the two empires for several years leading up to the war of 540–539 BC and the Fall of Babylon. In October 539 BC, Cyrus won a battle against the Babylonians at Opis, then took Sippar without a fight before finally capturing the city of Babylon on 12 October, where the Babylonian king Nabonidus was taken prisoner. Upon taking control of the city, Cyrus depicted himself in propaganda as restoring the divine order which had been disrupted by Nabonidus, who had promoted the cult of Sin rather than Marduk, and he also portrayed himself as restoring the heritage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by comparing himself to the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. The Hebrew Bible also unreservedly praises Cyrus for his actions in the conquest of Babylon, referring to him as Yahweh's anointed. He is credited with freeing the people of Judah from their exile and with authorizing the reconstruction of much of Jerusalem, including the Second Temple.

The tomb of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire In 530 BC, Cyrus died while on a military expedition against the Massagetae in Central Asia. He was succeeded by his eldest son Cambyses II, while his younger son Bardiya received a large territory in Central Asia. By 525 BC, Cambyses had successfully subjugated Phoenicia and Cyprus and was making preparations to invade Egypt with the newly created Persian navy. The great Pharaoh Amasis II had died in 526 BC and had been succeeded by Psamtik III, resulting in the defection of key Egyptian allies to the Persians. Psamtik positioned his army at Pelusium in the Nile Delta. He was soundly defeated by the Persians in the Battle of Pelusium before fleeing to Memphis, where the Persians defeated him and took him prisoner.

Herodotus depicts Cambyses as openly antagonistic to the Egyptian people and their gods, cults, temples and priests, in particular stressing the murder of the sacred bull Apis. He says that these actions led to a madness that caused him to kill his brother Bardiya (who Herodotus says was killed in secret), his own sister-wife and Croesus of Lydia. He then concludes that Cambyses completely lost his mind, and all later classical authors repeat the themes of Cambyses' impiety and madness. However, this is based on spurious information, as the epitaph of Apis from 524 BC shows that Cambyses participated in the funeral rites of Apis styling himself as pharaoh.

Following the conquest of Egypt, the Libyans and the Greeks of Cyrene and Barca in Libya surrendered to Cambyses and sent tribute without a fight. Cambyses then planned invasions of Carthage, the oasis of Ammon and Ethiopia. Herodotus claims that the naval invasion of Carthage was cancelled because the Phoenicians, who made up a large part of Cambyses' fleet, refused to take up arms against their own people, but modern historians doubt whether an invasion of Carthage was ever planned at all. However, Cambyses dedicated his efforts to the other two campaigns, aiming to improve the Empire's strategic position in Africa by conquering the Kingdom of Meroë and taking strategic positions in the western oases. To this end, he established a garrison at Elephantine consisting mainly of Jewish soldiers, who remained stationed at Elephantine throughout Cambyses' reign. The invasions of Ammon and Ethiopia themselves were failures. Herodotus claims that the invasion of Ethiopia was a failure due to the madness of Cambyses and the lack of supplies for his men, but archaeological evidence suggests that the expedition was not a failure, and a fortress at the Second Cataract of the Nile, on the border between Egypt and Kush, remained in use throughout the Achaemenid period.

The events surrounding Cambyses' death and Bardiya's succession are greatly debated as there are many conflicting accounts. According to Herodotus, as Bardiya's assassination had been committed in secret, the majority of Persians still believed him to be alive. This allowed two Magi to rise up against Cambyses, with one of them sitting on the throne able to impersonate Bardiya because of their remarkable physical resemblance and shared name (Smerdis in Herodotus' accounts). Ctesias writes that when Cambyses had Bardiya killed he immediately put the magus Sphendadates in his place as satrap of Bactria due to a remarkable physical resemblance.

Two of Cambyses' confidants then conspired to usurp Cambyses and put Sphendadates on the throne under the guise of Bardiya. According to the Behistun Inscription, written by the following king Darius the Great, a magus named Gaumata impersonated Bardiya and incited a revolution in Persia. Whatever the exact circumstances of the revolt, Cambyses heard news of it in the summer of 522 BC and began to return from Egypt, but he was wounded in the thigh in Syria and died of gangrene, so Bardiya's impersonator became king. The account of Darius is the earliest, and although the later historians all agree on the key details of the story, that a magus impersonated Bardiya and took the throne, this may have been a story created by Darius to justify his own usurpation. Iranologist Pierre Briant hypothesises that Bardiya was not killed by Cambyses, but waited until his death in the summer of 522 BC to claim his legitimate right to the throne as he was then the only male descendant of the royal family. Briant says that although the hypothesis of a deception by Darius is generally accepted today, "nothing has been established with certainty at the present time, given the available evidence".

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest extent, c. 500 BC According to the Behistun Inscription, Gaumata ruled for seven months before being overthrown in 522 BC by Darius the Great (Darius I) (Old Persian Daryavuš, "who holds firm the good", also known as Darayarahush or Darius the Great). The Magi, though persecuted, continued to exist, and a year following the death of the first pseudo-Smerdis (Gaumata), saw a second pseudo-Smerdis (named Vahyazdata) attempt a coup. The coup, though initially successful, failed.

Herodotus writes that the native leadership debated the best form of government for the empire. It was agreed that an oligarchy would divide them against one another, and democracy would bring about mob rule resulting in a charismatic leader resuming the monarchy. Therefore, they decided a new monarch was in order, particularly since they were in a position to choose him. Darius I was chosen monarch from among the leaders. He was cousin to Cambyses II and Bardiya (Smerdis), claiming Ariaramnes as his ancestor.[citation needed]

The Achaemenids thereafter consolidated areas firmly under their control. It was Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great who, by sound and far-sighted administrative planning, brilliant military manoeuvring, and a humanistic world view, established the greatness of the Achaemenids and, in less than thirty years, raised them from an obscure tribe to a world power. It was during the reign of Darius the Great (Darius I) that Persepolis was built (518–516 BC) and which would serve as capital for several generations of Achaemenid kings. Ecbatana (Hagmatana "City of Gatherings", modern: Hamadan) in Media was greatly expanded during this period and served as the summer capital.[citation needed]

Ever since the Macedonian king Amyntas I surrendered his country to the Persians in about 512–511, Macedonians and Persians were strangers no more as well. Subjugation of Macedonia was part of Persian military operations initiated by Darius the Great (521–486) in 513—after immense preparations—a huge Achaemenid army invaded the Balkans and tried to defeat the European Scythians roaming to the north of the Danube river. Darius' army subjugated several Thracian peoples, and virtually all other regions that touch the European part of the Black Sea, such as parts of nowadays Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, before it returned to Asia Minor. Darius left in Europe one of his commanders named Megabazus whose task was to accomplish conquests in the Balkans. The Persian troops subjugated gold-rich Thrace, the coastal Greek cities, as well as defeating and conquering the powerful Paeonians. Finally, Megabazus sent envoys to Amyntas, demanding acceptance of Persian domination, which the Macedonians did. The Balkans provided many soldiers for the multi-ethnic Achaemenid army. Many of the Macedonian and Persian elite intermarried, such as the Persian official Bubares who married Amyntas' daughter, Gygaea. Family ties the Macedonian rulers Amyntas and Alexander enjoyed with Bubares ensured them good relations with the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes I. The Persian invasion led indirectly to Macedonia's rise in power and Persia had some common interests in the Balkans; with Persian aid, the Macedonians stood to gain much at the expense of some Balkan tribes such as the Paeonians and Greeks. All in all, the Macedonians were "willing and useful Persian allies. Macedonian soldiers fought against Athens and Sparta in Xerxes' army. The Persians referred to both Greeks and Macedonians as Yauna ("Ionians", their term for "Greeks"), and to Macedonians specifically as Yaunã Takabara or "Greeks with hats that look like shields", possibly referring to the Macedonian kausia hat.

The Persian queen Atossa, Daughter of Cyrus the Great, sister-wife of Cambyses II, Darius the Great's wife, and mother of Xerxes I By the 5th century BC the Kings of Persia were either ruling over or had subordinated territories encompassing not just all of the Persian Plateau and all of the territories formerly held by the Assyrian Empire (Mesopotamia, the Levant, Cyprus and Egypt), but beyond this all of Anatolia and Armenia, as well as the Southern Caucasus and parts of the North Caucasus, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, all of Bulgaria, Paeonia, Thrace and Macedonia to the north and west, most of the Black Sea coastal regions, parts of Central Asia as far as the Aral Sea, the Oxus and Jaxartes to the north and north-east, the Hindu Kush and the western Indus basin (corresponding to modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) to the far east, parts of northern Arabia to the south, and parts of northern Libya to the south-west, and parts of Oman, China, and the UAE.

Greco-Persian Wars :

Map showing events of the first phases of the Greco-Persian Wars

Greek hoplite and Persian warrior depicted fighting, on an ancient kylix, 5th century BC The Ionian Revolt in 499 BC, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfaction of the Greek cities of Asia Minor with the tyrants appointed by Persia to rule them, along with the individual actions of two Milesian tyrants, Histiaeus and Aristagoras. In 499 BC, the then tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, launched a joint expedition with the Persian satrap Artaphernes to conquer Naxos, in an attempt to bolster his position in Miletus (both financially and in terms of prestige). The mission was a debacle, and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against the Persian king Darius the Great.[citation needed]

The Persians continued to reduce the cities along the west coast that still held out against them, before finally imposing a peace settlement in 493 BC on Ionia that was generally considered to be both just and fair. The Ionian Revolt constituted the first major conflict between Greece and the Achaemenid Empire, and as such represents the first phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, but Darius had vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for their support of the revolt. Moreover, seeing that the political situation in Greece posed a continued threat to the stability of his Empire, he decided to embark on the conquest of all of Greece. The first campaign of the invasion was to bring the territories in the Balkan peninsula back within the empire. The Persian grip over these territories had loosened following the Ionian Revolt. In 492 BC, the Persian general Mardonius re-subjugated Thrace and made Macedon a fully subordinate part of the empire; it had been a vassal as early as the late 6th century BC, but retained a great deal of autonomy. However, in 490 BC the Persian forces were defeated by the Athenians at the Battle of Marathon and Darius would die before having the chance to launch an invasion of Greece.

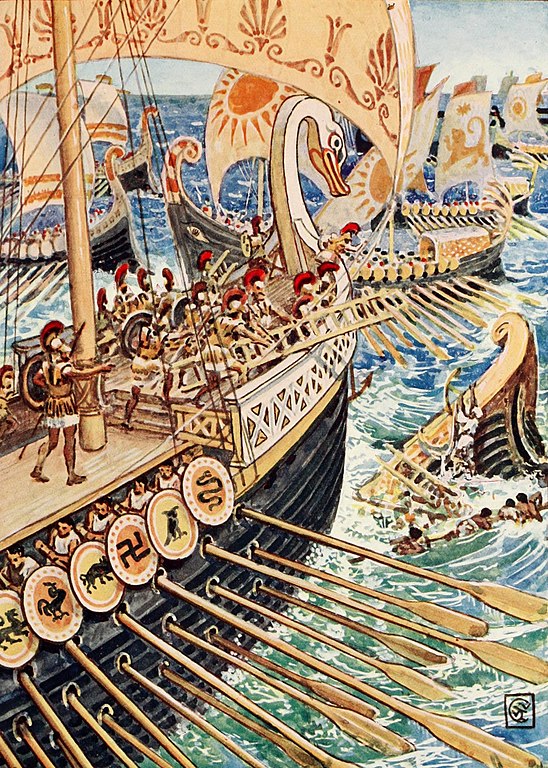

Xerxes I (485–465 BC, Old Persian Xšayarša "Hero Among Kings"), son of Darius I, vowed to complete the job. He organized a massive invasion aiming to conquer Greece. His army entered Greece from the north, meeting little or no resistance through Macedonia and Thessaly, but was delayed by a small Greek force for three days at Thermopylae. A simultaneous naval battle at Artemisium was tactically indecisive as large storms destroyed ships from both sides. The battle was stopped prematurely when the Greeks received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and retreated. The battle was a strategic victory for the Persians, giving them uncontested control of Artemisium and the Aegean Sea.[citation needed]

Following his victory at the Battle of Thermopylae, Xerxes sacked the evacuated city of Athens and prepared to meet the Greeks at the strategic Isthmus of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf. In 480 BC the Greeks won a decisive victory over the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis and forced Xerxes to retire to Sardis. The land army which he left in Greece under Mardonius retook Athens but was eventually destroyed in 479 BC at the Battle of Plataea. The final defeat of the Persians at Mycale encouraged the Greek cities of Asia to revolt, and the Persians lost all of their territories in Europe; Macedonia once again became independent.

Cultural

phase :

After Persia had been defeated at the Battle of Eurymedon (469 BC or 466 BC), military action between Greece and Persia was halted. When Artaxerxes I took power, he introduced a new Persian strategy of weakening the Athenians by funding their enemies in Greece. This indirectly caused the Athenians to move the treasury of the Delian League from the island of Delos to the Athenian acropolis. This funding practice inevitably prompted renewed fighting in 450 BC, where the Greeks attacked at the Battle of Cyprus. After Cimon's failure to attain much in this expedition, the Peace of Callias was agreed between Athens, Argos and Persia in 449 BC.

Artaxerxes I offered asylum to Themistocles, who was the winner of the Battle of Salamis, after Themistocles was ostracized from Athens. Also, Artaxerxes I gave him Magnesia, Myus, and Lampsacus to maintain him in bread, meat, and wine. In addition, Artaxerxes I gave him Palaescepsis to provide him with clothes, and he also gave him Percote with bedding for his house.

Achaemenid gold ornaments, Brooklyn Museum When Artaxerxes died in 424 BC at Susa, his body was taken to the tomb already built for him in the Naqsh-e Rustam Necropolis. It was Persian tradition that kings begin constructing their own tombs while they were still alive. Artaxerxes I was immediately succeeded by his eldest son Xerxes II, who was the only legitimate son of Artaxerxes. However, after a few days on the throne, he was assassinated while drunk by Pharnacyas and Menostanes on the orders of his illegitimate brother: Sogdianus who apparently had gained the support of his regions. He reigned for six months and fifteen days before being captured by his half-brother, Ochus, who had rebelled against him. Sogdianus was executed by being suffocated in ash because Ochus had promised he would not die by the sword, by poison or by hunger. Ochus then took the royal name Darius II. Darius' ability to defend his position on the throne ended the short power vacuum.[citation needed]

From 412 BC Darius II, at the insistence of Tissaphernes, gave support first to Athens, then to Sparta, but in 407 BC, Darius' son Cyrus the Younger was appointed to replace Tissaphernes and aid was given entirely to Sparta which finally defeated Athens in 404 BC. In the same year, Darius fell ill and died in Babylon. His death gave an Egyptian rebel named Amyrtaeus the opportunity to throw off Persian control over Egypt. At his death bed, Darius' Babylonian wife Parysatis pleaded with him to have her second eldest son Cyrus (the Younger) crowned, but Darius refused. Queen Parysatis favoured Cyrus more than her eldest son Artaxerxes II. Plutarch relates (probably on the authority of Ctesias) that the displaced Tissaphernes came to the new king on his coronation day to warn him that his younger brother Cyrus (the Younger) was preparing to assassinate him during the ceremony. Artaxerxes had Cyrus arrested and would have had him executed if their mother Parysatis had not intervened. Cyrus was then sent back as Satrap of Lydia, where he prepared an armed rebellion. Cyrus assembled a large army, including a contingent of Ten Thousand Greek mercenaries, and made his way deeper into Persia. The army of Cyrus was stopped by the royal Persian army of Artaxerxes II at Cunaxa in 401 BC, where Cyrus was killed. The Ten Thousand Greek Mercenaries including Xenophon were now deep in Persian territory and were at risk of attack. So they searched for others to offer their services to but eventually had to return to Greece.

Artaxerxes II was the longest reigning of the Achaemenid kings and it was during this 45-year period of relative peace and stability that many of the monuments of the era were constructed. Artaxerxes moved the capital back to Persepolis, which he greatly extended. Also the summer capital at Ecbatana was lavishly extended with gilded columns and roof tiles of silver and copper. The extraordinary innovation of the Zoroastrian shrines can also be dated to his reign, and it was probably during this period that Zoroastrianism spread from Armenia throughout Asia Minor and the Levant. The construction of temples, though serving a religious purpose, was not a purely selfless act, as they also served as an important source of income. From the Babylonian kings, the Achaemenids had taken over the concept of a mandatory temple tax, a one-tenth tithe which all inhabitants paid to the temple nearest to their land or other source of income. A share of this income called the Quppu Sha Sharri, "king's chest"—an ingenious institution originally introduced by Nabonidus—was then turned over to the ruler. In retrospect, Artaxerxes is generally regarded as an amiable man who lacked the moral fiber to be a really successful ruler. However, six centuries later Ardeshir I, founder of the second Persian Empire, would consider himself Artaxerxes' successor, a grand testimony to the importance of Artaxerxes to the Persian psyche.[citation needed]

Persian Empire timeline including important events and territorial evolution – 550–323 BC Artaxerxes II became involved in a war with Persia's erstwhile allies, the Spartans, who, under Agesilaus II, invaded Asia Minor. In order to redirect the Spartans' attention to Greek affairs, Artaxerxes II subsidized their enemies: in particular the Athenians, Thebans and Corinthians. These subsidies helped to engage the Spartans in what would become known as the Corinthian War. In 387 BC, Artaxerxes II betrayed his allies and came to an arrangement with Sparta, and in the Treaty of Antalcidas he forced his erstwhile allies to come to terms. This treaty restored control of the Greek cities of Ionia and Aeolis on the Anatolian coast to the Persians, while giving Sparta dominance on the Greek mainland. In 385 BC he campaigned against the Cadusians. Although successful against the Greeks, Artaxerxes II had more trouble with the Egyptians, who had successfully revolted against him at the beginning of his reign. An attempt to reconquer Egypt in 373 BC was completely unsuccessful, but in his waning years the Persians did manage to defeat a joint Egyptian–Spartan effort to conquer Phoenicia. He quashed the Revolt of the Satraps in 372–362 BC. He is reported to have had a number of wives. His main wife was Stateira, until she was poisoned by Artaxerxes II's mother Parysatis in about 400 BC. Another chief wife was a Greek woman of Phocaea named Aspasia (not the same as the concubine of Pericles). Artaxerxes II is said to have had more than 115 sons from 350 wives.

In 358 BC Artaxerxes II died and was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes III. In 355 BC, Artaxerxes III forced Athens to conclude a peace which required the city's forces to leave Asia Minor and to acknowledge the independence of its rebellious allies. Artaxerxes started a campaign against the rebellious Cadusians, but he managed to appease both of the Cadusian kings. One individual who successfully emerged from this campaign was Darius Codomannus, who later occupied the Persian throne as Darius III.[citation needed]

Artaxerxes III then ordered the disbanding of all the satrapal armies of Asia Minor, as he felt that they could no longer guarantee peace in the west and was concerned that these armies equipped the western satraps with the means to revolt. The order was however ignored by Artabazos II of Phrygia, who asked for the help of Athens in a rebellion against the king. Athens sent assistance to Sardis. Orontes of Mysia also supported Artabazos and the combined forces managed to defeat the forces sent by Artaxerxes III in 354 BC. However, in 353 BC, they were defeated by Artaxerxes III's army and were disbanded. Orontes was pardoned by the king, while Artabazos fled to the safety of the court of Philip II of Macedon. In around 351 BC, Artaxerxes embarked on a campaign to recover Egypt, which had revolted under his father, Artaxerxes II. At the same time a rebellion had broken out in Asia Minor, which, being supported by Thebes, threatened to become serious. Levying a vast army, Artaxerxes marched into Egypt, and engaged Nectanebo II. After a year of fighting the Egyptian Pharaoh, Nectanebo inflicted a crushing defeat on the Persians with the support of mercenaries led by the Greek generals Diophantus and Lamius. Artaxerxes was compelled to retreat and postpone his plans to reconquer Egypt. Soon after this defeat, there were rebellions in Phoenicia, Asia Minor and Cyprus.[citation needed]

Darius vase :

The "Darius Vase" at the Achaeological Museum of Naples. c. 340–320 BC

Detail of Darius, with a label in Greek giving his name In 343 BC, Artaxerxes committed responsibility for the suppression of the Cyprian rebels to Idrieus, prince of Caria, who employed 8,000 Greek mercenaries and forty triremes, commanded by Phocion the Athenian, and Evagoras, son of the elder Evagoras, the Cypriot monarch. Idrieus succeeded in reducing Cyprus. Artaxerxes initiated a counter-offensive against Sidon by commanding Belesys, satrap of Syria, and Mazaeus, satrap of Cilicia, to invade the city and to keep the Phoenicians in check. Both satraps suffered crushing defeats at the hands of Tennes, the Sidonese king, who was aided by 40,000 Greek mercenaries sent to him by Nectanebo II and commanded by Mentor of Rhodes. As a result, the Persian forces were driven out of Phoenicia.

After this, Artaxerxes personally led an army of 330,000 men against Sidon. Artaxerxes' army comprised 300,000-foot soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, 300 triremes, and 500 transports or provision ships. After gathering this army, he sought assistance from the Greeks. Though refused aid by Athens and Sparta, he succeeded in obtaining a thousand Theban heavy-armed hoplites under Lacrates, three thousand Argives under Nicostratus, and six thousand Æolians, Ionians, and Dorians from the Greek cities of Asia Minor. This Greek support was numerically small, amounting to no more than 10,000 men, but it formed, together with the Greek mercenaries from Egypt who went over to him afterwards, the force on which he placed his chief reliance, and to which the ultimate success of his expedition was mainly due. The approach of Artaxerxes sufficiently weakened the resolution of Tennes that he endeavoured to purchase his own pardon by delivering up 100 principal citizens of Sidon into the hands of the Persian king, and then admitting Artaxerxes within the defences of the town. Artaxerxes had the 100 citizens transfixed with javelins, and when 500 more came out as supplicants to seek his mercy, Artaxerxes consigned them to the same fate. Sidon was then burnt to the ground, either by Artaxerxes or by the Sidonian citizens. Forty thousand people died in the conflagration. Artaxerxes sold the ruins at a high price to speculators, who calculated on reimbursing themselves by the treasures which they hoped to dig out from among the ashes. Tennes was later put to death by Artaxerxes. Artaxerxes later sent Jews who supported the revolt to Hyrcania on the south coast of the Caspian Sea.

Second conquest of Egypt :

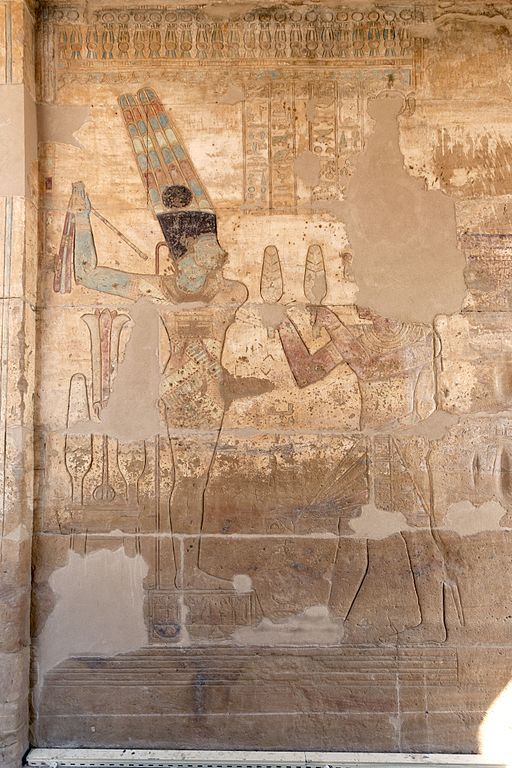

Relief showing Darius I offering lettuces to the Egyptian deity Amun-Ra Kamutef, Temple of Hibis

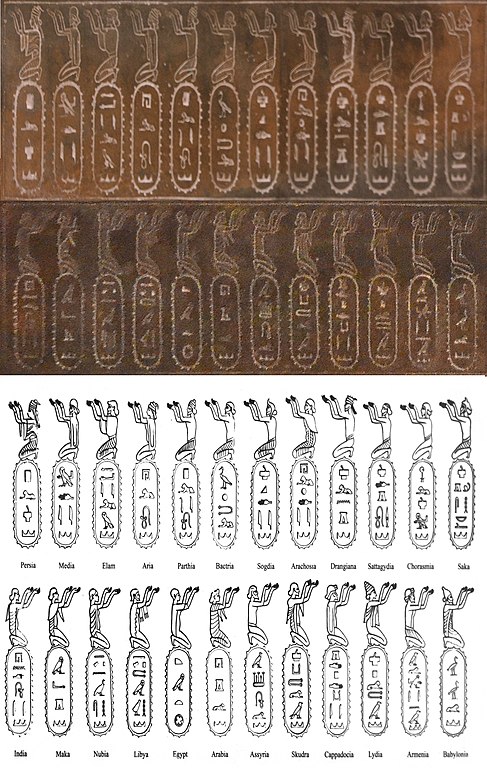

The 24 countries subject to the Achaemenid Empire at the time of Darius, on the Egyptian Statue of Darius I The reduction of Sidon was followed closely by the invasion of Egypt. In 343 BC, Artaxerxes, in addition to his 330,000 Persians, had now a force of 14,000 Greeks furnished by the Greek cities of Asia Minor: 4,000 under Mentor, consisting of the troops that he had brought to the aid of Tennes from Egypt; 3,000 sent by Argos; and 1000 from Thebes. He divided these troops into three bodies, and placed at the head of each a Persian and a Greek. The Greek commanders were Lacrates of Thebes, Mentor of Rhodes and Nicostratus of Argos while the Persians were led by Rhossaces, Aristazanes, and Bagoas, the chief of the eunuchs. Nectanebo II resisted with an army of 100,000 of whom 20,000 were Greek mercenaries. Nectanebo II occupied the Nile and its various branches with his large navy.[citation needed]

The character of the country, intersected by numerous canals and full of strongly fortified towns, was in his favour and Nectanebo II might have been expected to offer a prolonged, if not even a successful, resistance. However, he lacked good generals, and, over-confident in his own powers of command, he was out-manoeuvred by the Greek mercenary generals and his forces were eventually defeated by the combined Persian armies at the Battle of Pelusium (343 BC). After his defeat, Nectanebo hastily fled to Memphis, leaving the fortified towns to be defended by their garrisons. These garrisons consisted of partly Greek and partly Egyptian troops; between whom jealousies and suspicions were easily sown by the Persian leaders. As a result, the Persians were able to rapidly reduce numerous towns across Lower Egypt and were advancing upon Memphis when Nectanebo decided to quit the country and flee southwards to Ethiopia. The Persian army completely routed the Egyptians and occupied the Lower Delta of the Nile. Following Nectanebo fleeing to Ethiopia, all of Egypt submitted to Artaxerxes. The Jews in Egypt were sent either to Babylon or to the south coast of the Caspian Sea, the same location that the Jews of Phoenicia had earlier been sent.[citation needed]

After this victory over the Egyptians, Artaxerxes had the city walls destroyed, started a reign of terror, and set about looting all the temples. Persia gained a significant amount of wealth from this looting. Artaxerxes also raised high taxes and attempted to weaken Egypt enough that it could never revolt against Persia. For the 10 years that Persia controlled Egypt, believers in the native religion were persecuted and sacred books were stolen. Before he returned to Persia, he appointed Pherendares as satrap of Egypt. With the wealth gained from his reconquering Egypt, Artaxerxes was able to amply reward his mercenaries. He then returned to his capital having successfully completed his invasion of Egypt.[citation needed]

After his success in Egypt, Artaxerxes returned to Persia and spent the next few years effectively quelling insurrections in various parts of the Empire so that a few years after his conquest of Egypt, the Persian Empire was firmly under his control. Egypt remained a part of the Persian Empire until Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt.[citation needed]

After the conquest of Egypt, there were no more revolts or rebellions against Artaxerxes. Mentor and Bagoas, the two generals who had most distinguished themselves in the Egyptian campaign, were advanced to posts of the highest importance. Mentor, who was governor of the entire Asiatic seaboard, was successful in reducing to subjection many of the chiefs who during the recent troubles had rebelled against Persian rule. In the course of a few years Mentor and his forces were able to bring the whole Asian Mediterranean coast into complete submission and dependence.[citation needed]

Bagoas went back to the Persian capital with Artaxerxes, where he took a leading role in the internal administration of the Empire and maintained tranquillity throughout the rest of the Empire. During the last six years of the reign of Artaxerxes III, the Persian Empire was governed by a vigorous and successful government.

The Persian forces in Ionia and Lycia regained control of the Aegean and the Mediterranean Sea and took over much of Athens' former island empire. In response, Isocrates of Athens started giving speeches calling for a 'crusade against the barbarians' but there was not enough strength left in any of the Greek city-states to answer his call.

Although there were no rebellions in the Persian Empire itself, the growing power and territory of Philip II of Macedon in Macedon (against which Demosthenes was in vain warning the Athenians) attracted the attention of Artaxerxes. In response, he ordered that Persian influence was to be used to check and constrain the rising power and influence of the Macedonian kingdom. In 340 BC, a Persian force was dispatched to assist the Thracian prince, Cersobleptes, to maintain his independence. Sufficient effective aid was given to the city of Perinthus that the numerous and well-appointed army with which Philip had commenced his siege of the city was compelled to give up the attempt. By the last year of Artaxerxes' rule, Philip II already had plans in place for an invasion of the Persian Empire, which would crown his career, but the Greeks would not unite with him.

In 338 BC Artaxerxes was poisoned by Bagoas with the assistance of a physician.

Fall of the empire :

The Battle of Issus, between Alexander the Great on horseback to the left, and Darius III in the chariot to the right, represented in a Pompeii mosaic dated 1st century BC – Naples National Archaeological Museum.

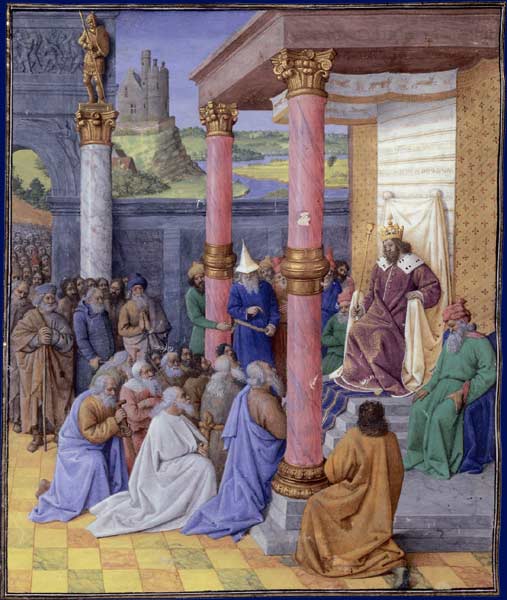

Alexander's first victory over Darius, the Persian king depicted in medieval European style in the 15th century romance The History of Alexander's Battles Artaxerxes III was succeeded by Artaxerxes IV Arses, who before he could act was also poisoned by Bagoas. Bagoas is further said to have killed not only all Arses' children, but many of the other princes of the land. Bagoas then placed Darius III, a nephew of Artaxerxes IV, on the throne. Darius III, previously Satrap of Armenia, personally forced Bagoas to swallow poison. In 334 BC, when Darius was just succeeding in subduing Egypt again, Alexander and his battle-hardened troops invaded Asia Minor.[citation needed]

Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) defeated the Persian armies at Granicus (334 BC), followed by Issus (333 BC), and lastly at Gaugamela (331 BC). Afterwards, he marched on Susa and Persepolis which surrendered in early 330 BC. From Persepolis, Alexander headed north to Pasargadae where he visited the tomb of Cyrus, the burial of the man whom he had heard of from the Cyropedia.[citation needed]

In the ensuing chaos created by Alexander's invasion of Persia, Cyrus's tomb was broken into and most of its luxuries were looted. When Alexander reached the tomb, he was horrified by the manner in which it had been treated, and questioned the Magi, putting them on trial. By some accounts, Alexander's decision to put the Magi on trial was more an attempt to undermine their influence and display his own power than a show of concern for Cyrus's tomb. Regardless, Alexander the Great ordered Aristobulus to improve the tomb's condition and restore its interior, showing respect for Cyrus. From there he headed to Ecbatana, where Darius III had sought refuge.

Darius III was taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman. As Alexander approached, Bessus had his men murder Darius III and then declared himself Darius' successor, as Artaxerxes V, before retreating into Central Asia leaving Darius' body in the road to delay Alexander, who brought it to Persepolis for an honourable funeral. Bessus would then create a coalition of his forces, in order to create an army to defend against Alexander. Before Bessus could fully unite with his confederates at the eastern part of the empire, Alexander, fearing the danger of Bessus gaining control, found him, put him on trial in a Persian court under his control, and ordered his execution in a "cruel and barbarous manner."

Alexander

generally kept the original Achaemenid administrative structure,

leading some scholars to dub him as "the last of the Achaemenids".

Upon Alexander's death in 323 BC, his empire was divided among his

generals, the Diadochi, resulting in a number of smaller states.

The largest of these, which held sway over the Iranian plateau,

was the Seleucid Empire, ruled by Alexander's general Seleucus I

Nicator. Native Iranian rule would be restored by the Parthians

of northeastern Iran over the course of the 2nd century BC.

Frataraka dynasty ruler Vadfradad I (Autophradates I). 3rd century BC. Istakhr (Persepolis) mint Several later Persian rulers, forming the Frataraka dynasty, are known to have acted as representatives of the Seleucids in the region of Fars. They ruled from the end of the 3rd century BC to the beginning of the 2nd century BC, and Vahbarz or Vadfradad I obtained independence circa 150 BC, when Seleucid power waned in the areas of southwestern Persia and the Persian Gulf region.

Kings of Persis, under the Parthian Empire :

Darev I (Darios I) used for the first time the title of mlk (King). 2nd century BC During an apparent transitional period, corresponding to the reigns of Vadfradad II and another uncertain king, no titles of authority appeared on the reverse of their coins. The earlier title prtrk' zy alhaya (Frataraka) had disappeared. Under Darev I however, the new title of mlk, or king, appeared, sometimes with the mention of prs (Persis), suggesting that the kings of Persis had become independent rulers.

When the Parthian Arsacid king Mithridates I (c. 171–138 BC) took control of Persis, he left the Persian dynasts in office, known as the Kings of Persis, and they were allowed to continue minting coins with the title of mlk ("King").

Sasanian

Empire :

Kingdom

of Pontus :

Winged sphinx from the Palace of Darius the Great at Susa, Louvre Both the later dynasties of the Parthians and Sasanians would on occasion claim Achaemenid descent. Recently there has been some corroboration for the Parthian claim to Achaemenid ancestry via the possibility of an inherited disease (neurofibromatosis) demonstrated by the physical descriptions of rulers and from evidence of familial disease on ancient coinage.

Causes

of decline :

Another factor contributing to the decline of the Empire, in the period following Xerxes, was its failure to ever mold the many subject nations into a whole; the creation of a national identity was never attempted. This lack of cohesion eventually affected the efficiency of the military.

Government :

Daric of Artaxerxes II Cyrus the Great founded the empire as a multi-state empire, governed from four capital cities: Pasargadae, Babylon, Susa and Ecbatana. The Achaemenids allowed a certain amount of regional autonomy in the form of the satrapy system. A satrapy was an administrative unit, usually organized on a geographical basis. A 'satrap' (governor) was the governor who administered the region, a 'general' supervised military recruitment and ensured order, and a 'state secretary' kept the official records. The general and the state secretary reported directly to the satrap as well as the central government. At differing times, there were between 20 and 30 satrapies.

Cyrus the Great created an organized army including the Immortals unit, consisting of 10,000 highly trained soldiers Cyrus also formed an innovative postal system throughout the empire, based on several relay stations called Chapar Khaneh.

Achaemenid

coinage :

Tax districts :

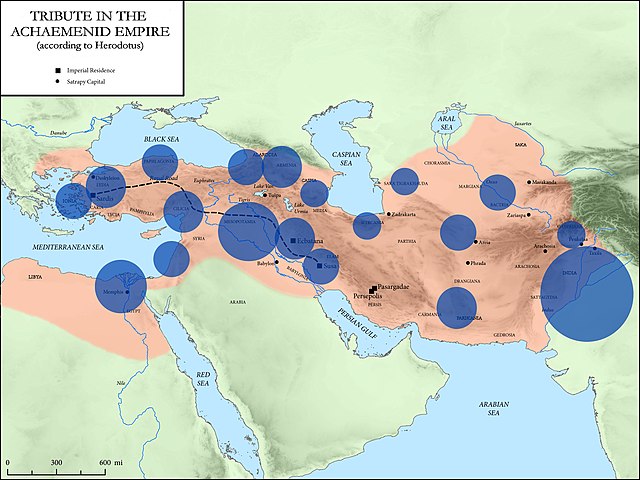

Volume of annual tribute per district, in the Achaemenid Empire, according to Herodotus Darius also introduced a regulated and sustainable tax system that was precisely tailored to each satrapy, based on their supposed productivity and their economic potential. For instance, Babylon was assessed for the highest amount and for a startling mixture of commodities – 1000 silver talents, four months supply of food for the army. India was clearly already fabled for its gold; Egypt was known for the wealth of its crops; it was to be the granary of the Persian Empire (as later of Rome's) and was required to provide 120,000 measures of grain in addition to 700 talents of silver. This was exclusively a tax levied on subject peoples. There is evidence that conquered and/or rebellious enemies could be sold into slavery. Alongside its other innovations in administration and taxation, the Achaemenids may have been the first government in the ancient Near East to register private slave sales and tax them using an early form of sales tax.

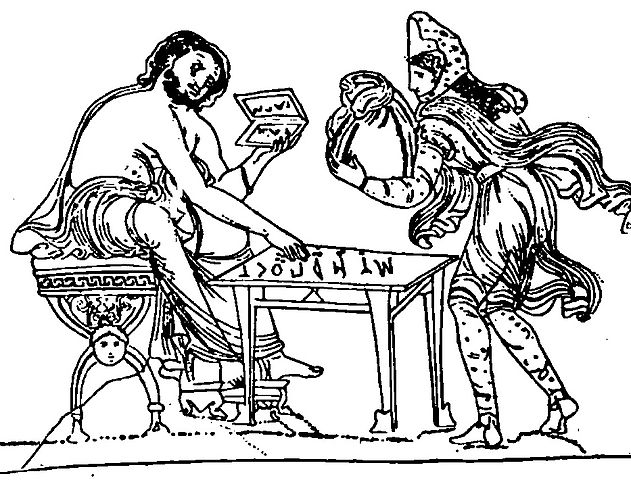

Achaemenid tax collector, calculating on an Abax or Abacus, according to the Darius Vase (340–320 BC) Other accomplishments of Darius' reign included codification of the data, a universal legal system, and construction of a new capital at Persepolis.

Transportation

and Communication :

The satrapies were linked by a 2,500-kilometer highway, the most impressive stretch being the Royal Road from Susa to Sardis, built by command of Darius I. It featured stations and caravanserais at specific intervals. The relays of mounted couriers (the angarium) could reach the remotest of areas in fifteen days. Herodotus observes that "there is nothing in the world that travels faster than these Persian couriers. Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night stays these courageous couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds." Despite the relative local independence afforded by the satrapy system, royal inspectors, the "eyes and ears of the king", toured the empire and reported on local conditions.[citation needed]

Another highway of commerce was the Great Khorasan Road, an informal mercantile route that originated in the fertile lowlands of Mesopotamia and snaked through the Zagros highlands, through the Iranian plateau and Afghanistan into the Central Asian regions of Samarkand, Merv and Ferghana, allowing for the construction of frontier cities like Cyropolis. Following Alexander's conquests, this highway allowed for the spread of cultural syncretic fusions like Greco-Buddhism into Central Asia and China, as well as empires like the Kushan, Indo-Greek and Parthian to profit from trade between East and West. This route was greatly rehabilitated and formalized during the Abbasid Caliphate, during which it developed into a major component of the famed Silk Road.

Military

:

Military composition :

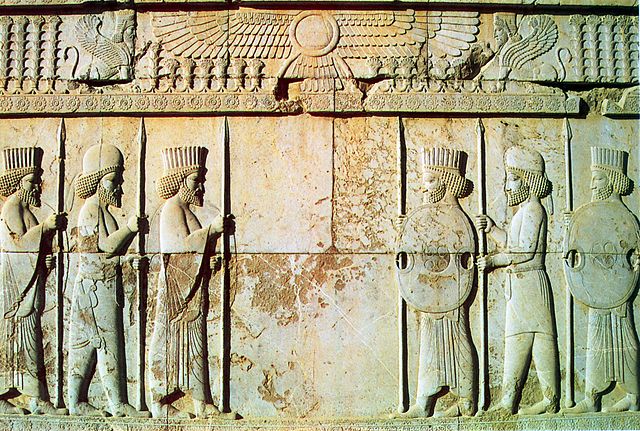

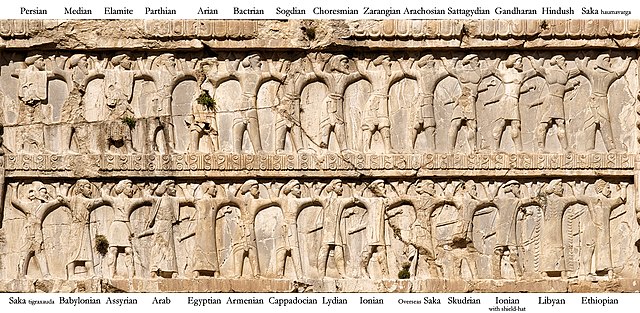

Relief of throne-bearing soldiers in their native clothing at the tomb of Xerxes I, demonstrating the satrapies under his rule The empire's great armies were, like the empire itself, very diverse, having: Persians, Macedonians, European Thracians, Paeonians, Medes, Achaean Greeks, Cissians, Hyrcanians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Bactrians, Sacae, Arians, Parthians, Caucasian Albanians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, Gandarians, Dadicae, Caspians, Sarangae, Pactyes, Utians, Mycians, Phoenicians, Judeans, Egyptians, Cyprians, Cilicians, Pamphylians, Lycians, Dorians of Asia, Carians, Ionians, Aegean islanders, Aeolians, Greeks from Pontus, Paricanians, Arabians, Ethiopians of Africa, Ethiopians of Baluchistan, Libyans, Paphlagonians, Ligyes, Matieni, Mariandyni, Cappadocians, Phrygians, Armenians, Lydians, Mysians, Asian Thracians, Lasonii, Milyae, Moschi, Tibareni, Macrones, Mossynoeci, Mares, Colchians, Alarodians, Saspirians, Red Sea islanders, Sagartians, Indians, Eordi, Bottiaei, Chalcidians, Brygians, Pierians, Perrhaebi, Enienes, Dolopes, and Magnesians.[citation needed]

Infantry :

Achaemenid king killing a Greek hoplite. c. 500 BC–475 BC, at the time of Xerxes I. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Persian soldiers (left) fighting against Scythians. Cylinder seal impression The Achaemenid infantry consisted of three groups: the Immortals, the Sparabara, and the Takabara, though in the later years of the Achaemenid Empire, the Cardaces, were introduced.[citation needed]

The Immortals were described by Herodotus as being heavy infantry, led by Hydarnes, that were kept constantly at a strength of exactly 10,000 men. He claimed that the unit's name stemmed from the custom that every killed, seriously wounded, or sick member was immediately replaced with a new one, maintaining the numbers and cohesion of the unit. They had wicker shields, short spears, swords or large daggers, bow and arrow. Underneath their robes they wore scale armour coats. The spear counter balances of the common soldiery were of silver; to differentiate commanding ranks, the officers' spear butt-spikes were golden. Surviving Achaemenid coloured glazed bricks and carved reliefs represent the Immortals as wearing elaborate robes, hoop earrings and gold jewellery, though these garments and accessories were most likely worn only for ceremonial occasions.

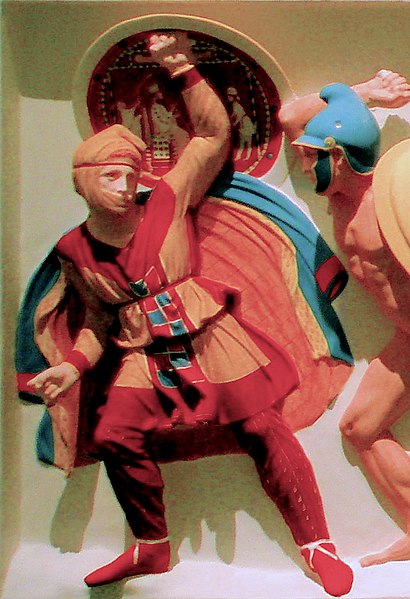

Color reconstruction of Achaemenid infantry on the Alexander Sarcophagus (end of 4th century BC) The Sparabara were usually the first to engage in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy. Although not much is known about them today, it is believed that they were the backbone of the Persian army who formed a shield wall and used their two-metre-long spears to protect more vulnerable troops such as archers from the enemy. The Sparabara were taken from the full members of Persian society, they were trained from childhood to be soldiers and when not called out to fight on campaigns in distant lands they practised hunting on the vast plains of Persia. However, when all was quiet and the Pax Persica held true, the Sparabara returned to normal life farming the land and grazing their herds. Because of this they lacked true professional quality on the battlefield, yet they were well trained and courageous to the point of holding the line in most situations long enough for a counter-attack. They were armoured with quilted linen and carried large rectangular wicker shields as a form of light manoeuvrable defence. This, however, left them at a severe disadvantage against heavily armoured opponents such as the hoplite, and his two-metre-long spear was not able to give the Sparabara ample range to plausibly engage a trained phalanx. The wicker shields were able to effectively stop arrows but not strong enough to protect the soldier from spears. However, the Sparabara could deal with most other infantry, including trained units from the East.[citation needed]

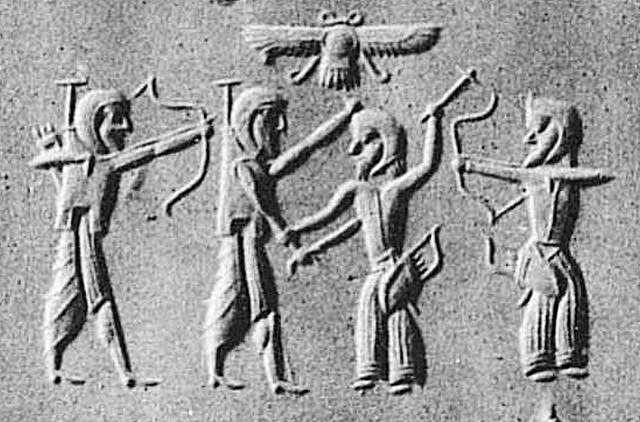

The Achaemenids relied heavily on archery. Major contributing nations were the Scythians, Medes, Persians, and the Elamites. The composite bow was used by the Persians and Medes, who adopted it from the Scythians and transmitted it to other nations, including the Greeks. The socketed, three-bladed (also known as trilobate or Scythian) arrowheads made of copper alloy was the arrowhead variant normally used by the Achaemenid army. This variant required more expertise and precision to build.

The Takabara were a rare unit who were a tough type of peltasts. They tended to fight with their own native weapons which would have included a crescent-shaped light wickerwork shield and axes as well as light linen cloth and leather. The Takabara were recruited from territories that incorporated modern Iran.

Cavalry :

Seal of Darius the Great hunting in a chariot, reading "I am Darius, the Great King" in Old Persian, as well as in Elamite and Babylonian. The word 'great' only appears in Babylonian. British Museum The armoured Persian horsemen and their death dealing chariots were invincible. No man dared face them

—

Herodotus

Achaemenid calvalryman in the satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia, Altikulaç Sarcophagus, early 4th century BC In the later years of the Achaemenid Empire, the chariot archer had become merely a ceremonial part of the Persian army, yet in the early years of the Empire, their use was widespread. The chariot archers were armed with spears, bows, arrows, swords, and scale armour. The horses were also suited with scale armour similar to scale armour of the Sassanian cataphracts. The chariots would contain imperial symbols and decorations.

Armoured cavalry: Achaemenid Dynast of Hellespontine Phrygia attacking a Greek psiloi, Altikulaç Sarcophagus, early 4th century BC The horses used by the Achaemenids for cavalry were often suited with scale armour, like most cavalry units. The riders often had the same armour as Infantry units, wicker shields, short spears, swords or large daggers, bow and arrow and scale armour coats. The camel cavalry was different, because the camels and sometimes the riders, were provided little protection against enemies, yet when they were offered protection, they would have spears, swords, bow, arrow, and scale armour. The camel cavalry was first introduced into the Persian army by Cyrus the Great, at the Battle of Thymbra. The elephant was most likely introduced into the Persian army by Darius I after his conquest of the Indus Valley. They may have been used in Greek campaigns by Darius and Xerxes I, but Greek accounts only mention 15 of them being used at the Battle of Gaugamela.[citation needed]

Navy

:

Reconstitution of Persian landing ships at the Battle of Marathon At first the ships were built in Sidon by the Phoenicians; the first Achaemenid ships measured about 40 meters in length and 6 meters in width, able to transport up to 300 Persian troops at any one trip. Soon, other states of the empire were constructing their own ships, each incorporating slight local preferences. The ships eventually found their way to the Persian Gulf. Persian naval forces laid the foundation for a strong Persian maritime presence in the Persian Gulf. Persians were not only stationed on islands in the Persian Gulf, but also had ships often of 100 to 200 capacity patrolling the empire's various rivers including the Karun, Tigris and Nile in the west, as well as the Indus.

Greek ships against Achaemenid ships at the Battle of Salamis (Check for the symbols on the shield. Many symbols are still used by Aryans) The Achaemenid navy established bases located along the Karun, and in Bahrain, Oman, and Yemen. The Persian fleet was not only used for peace-keeping purposes along the Karun but also opened the door to trade with India via the Persian Gulf. Darius's navy was in many ways a world power at the time, but it would be Artaxerxes II who in the summer of 397 BC would build a formidable navy, as part of a rearmament which would lead to his decisive victory at Knidos in 394 BC, re-establishing Achaemenid power in Ionia. Artaxerxes II would also utilize his navy to later on quell a rebellion in Egypt.

The construction material of choice was wood, but some armoured Achaemenid ships had metallic blades on the front, often meant to slice enemy ships using the ship's momentum. Naval ships were also equipped with hooks on the side to grab enemy ships, or to negotiate their position. The ships were propelled by sails or manpower. The ships the Persians created were unique. As far as maritime engagement, the ships were equipped with two mangonels that would launch projectiles such as stones, or flammable substances.

Xenophon describes his eyewitness account of a massive military bridge created by joining 37 Persian ships across the Tigris. The Persians utilized each boat's buoyancy, in order to support a connected bridge above which supply could be transferred. Herodotus also gives many accounts of Persians utilizing ships to build bridges.

Darius the Great, in an attempt to subdue the Scythian horsemen north of the Black Sea, crossed over at the Bosphorus, using an enormous bridge made by connecting Achaemenid boats, then marched up to the Danube, crossing it by means of a second boat bridge. The bridge over the Bosphorus essentially connected the nearest tip of Asia to Europe, encompassing at least some 1000 meters of open water if not more. Herodotus describes the spectacle, and calls it the "bridge of Darius":

"Strait

called Bosphorus, across which the bridge of Darius had been thrown

is hundred and twenty furlongs in length, reaching from the Euxine,

to the Propontis. The Propontis is five hundred furlongs across,

and fourteen hundred long. Its waters flow into the Hellespont,

the length of which is four hundred furlongs ..."

Culture :

Iconic relief of lion and bull fighting, Apadana of Persepolis

Achaemenid golden bowl with lioness imagery of Mazandaran

The ruins of Persepolis Herodotus, in his mid-5th century BC account of Persian residents of the Pontus, reports that Persian youths, from their fifth year to their twentieth year, were instructed in three things—to ride a horse, to draw a bow, and to speak the Truth. He further notes that :

The

most disgraceful thing in the world [the Persians] think, is to

tell a lie; the next worst, to owe a debt: because, among other

reasons, the debtor is obliged to tell lies.[citation needed]

I

was not a lie-follower, I was not a doer of wrong ... According

to righteousness I conducted myself. Neither to the weak or to the

powerful did I do wrong. The man who cooperated with my house, him

I rewarded well; who so did injury, him I punished well.[citation

needed]

I

smote them and took prisoner nine kings. One was Gaumata by name,

a Magian; he lied; thus he said: I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus

... One, Acina by name, an Elamite; he lied; thus he said: I am

king in Elam ... One, Nidintu-Bel by name, a Babylonian; he lied;

thus he said: I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus.[citation

needed]

The

Lie made them rebellious, so that these men deceived the people.

Thou

who shalt be king hereafter, protect yourself vigorously from the

Lie; the man who shall be a lie-follower, him do thou punish well,

if thus thou shall think. May my country be secure![citation needed]

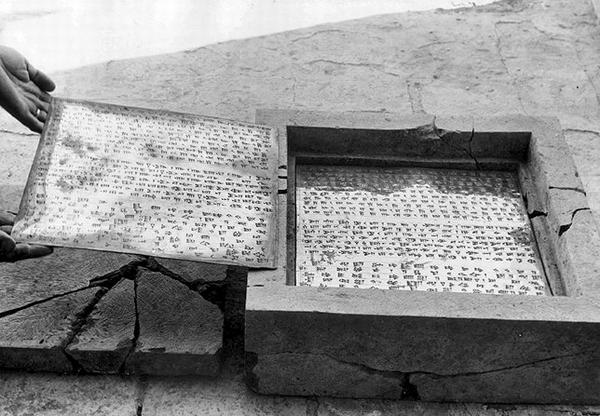

Gold foundation tablets of Darius I for the Apadana Palace, in their original stone box. The Apadana coin hoard had been deposited underneath c. 510 BC

One of the two gold deposition plates. Two more were in silver. They all had the same trilingual inscription (DPh inscription) During the reign of Cyrus and Darius, and as long as the seat of government was still at Susa in Elam, the language of the chancellery was Elamite. This is primarily attested in the Persepolis fortification and treasury tablets that reveal details of the day-to-day functioning of the empire. In the grand rock-face inscriptions of the kings, the Elamite texts are always accompanied by Akkadian (Babylonian dialect) and Old Persian inscriptions, and it appears that in these cases, the Elamite texts are translations of the Old Persian ones. It is then likely that although Elamite was used by the capital government in Susa, it was not a standardized language of government everywhere in the empire. The use of Elamite is not attested after 458 BC.

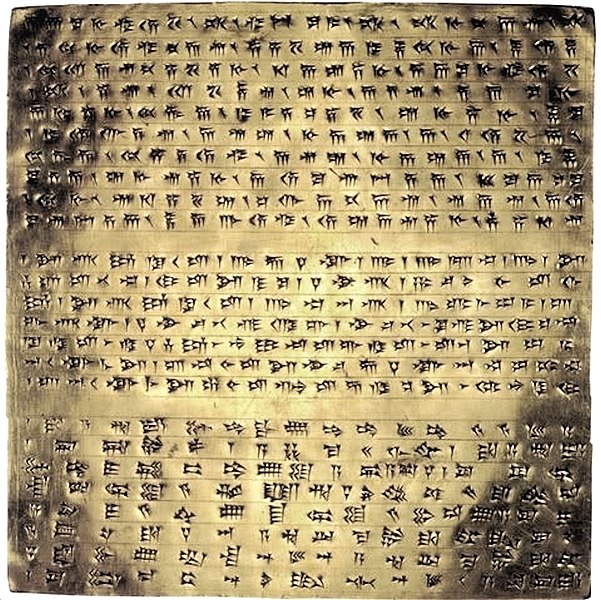

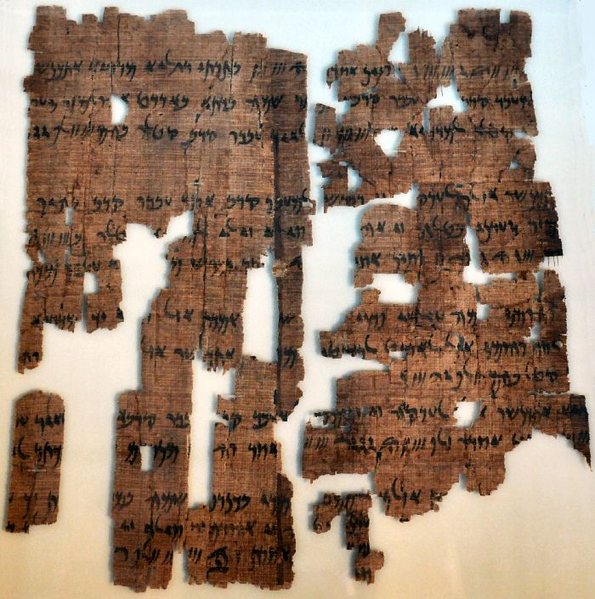

A section of the Old Persian part of the trilingual Behistun inscription. Other versions are in Babylonian and Elamite

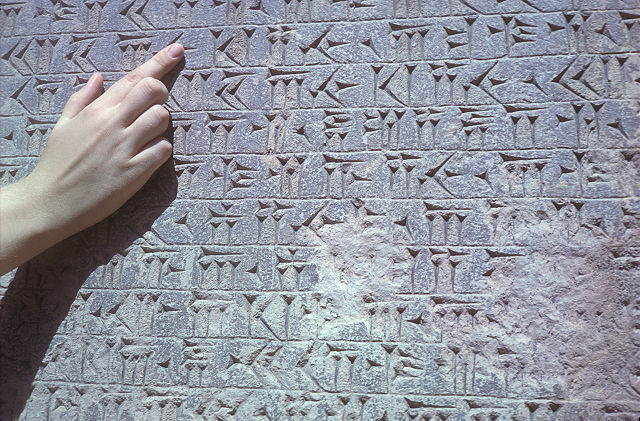

A copy of the Behistun inscription in Aramaic on a papyrus. Aramaic was the lingua franca of the empire Following the conquest of Mesopotamia, the Aramaic language (as used in that territory) was adopted as a "vehicle for written communication between the different regions of the vast empire with its different peoples and languages. The use of a single official language, which modern scholarship has dubbed "Official Aramaic" or "Imperial Aramaic", can be assumed to have greatly contributed to the astonishing success of the Achaemenids in holding their far-flung empire together for as long as they did." In 1955, Richard Frye questioned the classification of Imperial Aramaic as an "official language", noting that no surviving edict expressly and unambiguously accorded that status to any particular language. Frye reclassifies Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of the Achaemenid territories, suggesting then that the Achaemenid-era use of Aramaic was more pervasive than generally thought. Many centuries after the fall of the empire, Aramaic script and—as ideograms—Aramaic vocabulary would survive as the essential characteristics of the Pahlavi writing system.

Although Old Persian also appears on some seals and art objects, that language is attested primarily in the Achaemenid inscriptions of Western Iran, suggesting then that Old Persian was the common language of that region. However, by the reign of Artaxerxes II, the grammar and orthography of the inscriptions was so "far from perfect" that it has been suggested that the scribes who composed those texts had already largely forgotten the language, and had to rely on older inscriptions, which they to a great extent reproduced verbatim.

When the occasion demanded, Achaemenid administrative correspondence was conducted in Greek, making it a widely used bureaucratic language. Even though the Achaemenids had extensive contacts with the Greeks and vice versa, and had conquered many of the Greek-speaking areas both in Europe and Asia Minor during different periods of the empire, the native Old Iranian sources provide no indication of Greek linguistic evidence. However, there is plenty of evidence (in addition to the accounts of Herodotus) that Greeks, apart from being deployed and employed in the core regions of the empire, also evidently lived and worked in the heartland of the Achaemenid Empire, namely Iran. For example, Greeks were part of the various ethnicities that constructed Darius' palace in Susa, apart from the Greek inscriptions found nearby there, and one short Persepolis tablet written in Greek.

Customs :

An Achaemenid drinking vessel Herodotus mentions that the Persians were invited to great birthday feasts (Herodotus, Histories 8), which would be followed by many desserts, a treat which they reproached the Greeks for omitting from their meals. He also observed that the Persians drank wine in large quantities and used it even for counsel, deliberating on important affairs when drunk, and deciding the next day, when sober, whether to act on the decision or set it aside. Bowing to superiors, or royalty was one of the many Persian customs adopted by Alexander the Great.[citation needed]

Religion

:

It was during the Achaemenid period that Zoroastrianism reached South-Western Iran, where it came to be accepted by the rulers and through them became a defining element of Persian culture. The religion was not only accompanied by a formalization of the concepts and divinities of the traditional Iranian pantheon but also introduced several novel ideas, including that of free will. Under the patronage of the Achaemenid kings, and by the 5th century BC as the de facto religion of the state, Zoroastrianism reached all corners of the empire.

Bas-relief of Farvahar at Persepolis During the reign of Artaxerxes I and Darius II, Herodotus wrote "[the Persians] have no images of the gods, no temples nor altars, and consider the use of them a sign of folly. This comes, I think, from their not believing the gods to have the same nature with men, as the Greeks imagine." He claims the Persians offer sacrifice to: "the sun and moon, to the earth, to fire, to water, and to the winds. These are the only gods whose worship has come down to them from ancient times. At a later period they began the worship of Urania, which they borrowed from the Arabians and Assyrians. Mylitta is the name by which the Assyrians know this goddess, to whom the Persians referred as Anahita." (The original name here is Mithra, which has since been explained to be a confusion of Anahita with Mithra, understandable since they were commonly worshipped together in one temple).[citation needed]

From the Babylonian scholar-priest Berosus, who—although writing over seventy years after the reign of Artaxerxes II Mnemon—records that the emperor had been the first to make cult statues of divinities and have them placed in temples in many of the major cities of the empire. Berosus also substantiates Herodotus when he says the Persians knew of no images of gods until Artaxerxes II erected those images. On the means of sacrifice, Herodotus adds "they raise no altar, light no fire, pour no libations." This sentence has been interpreted to identify a critical (but later) accretion to Zoroastrianism. An altar with a wood-burning fire and the Yasna service at which libations are poured are all clearly identifiable with modern Zoroastrianism, but apparently, were practices that had not yet developed in the mid-5th century. Boyce also assigns that development to the reign of Artaxerxes II (4th century BC), as an orthodox response to the innovation of the shrine cults.[citation needed]

Herodotus also observed that "no prayer or offering can be made without a magus present" but this should not be confused with what is today understood by the term magus, that is a magupat (modern Persian: mobed), a Zoroastrian priest. Nor does Herodotus' description of the term as one of the tribes or castes of the Medes necessarily imply that these magi were Medians. They simply were a hereditary priesthood to be found all over Western Iran and although (originally) not associated with any one specific religion, they were traditionally responsible for all ritual and religious services. Although the unequivocal identification of the magus with Zoroastrianism came later (Sassanid era, 3rd–7th century AD), it is from Herodotus' magus of the mid-5th century that Zoroastrianism was subject to doctrinal modifications that are today considered to be revocations of the original teachings of the prophet. Also, many of the ritual practices described in the Avesta's Vendidad (such as exposure of the dead) were already practised by the magu of Herodotus' time.[citation needed]

Art

and architecture :

Achaemenid art includes frieze reliefs, Metalwork such as the Oxus Treasure, decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship (masonry, carpentry, etc.), and gardening. Although the Persians took artists, with their styles and techniques, from all corners of their empire, they produced not simply a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style. Cyrus the Great in fact had an extensive ancient Iranian heritage behind him; the rich Achaemenid gold work, which inscriptions suggest may have been a speciality of the Medes, was for instance in the tradition of the delicate metalwork found in Iron Age II times at Hasanlu and still earlier at Marlik.[citation needed]

Reconstruction of the Palace of Darius at Susa. The palace served as a model for Persepolis

Lion on a decorative panel from Darius I the Great's palace, Louvre One of the most remarkable examples of both Achaemenid architecture and art is the grand palace of Persepolis, and its detailed workmanship, coupled with its grand scale. In describing the construction of his palace at Susa, Darius the Great records that:

Yaka timber was brought from Gandhar and from Carmania. The gold was brought from Sardis and from Bactria ... the precious stone lapis-lazuli and carnelian ... was brought from Sogdiana. The turquoise from Chorasmia, the silver and ebony from Egypt, the ornamentation from Ionia, the ivory from Ethiopia and from Sindh and from Arachosia. The stone-cutters who wrought the stone, those were Ionians and Sardians. The goldsmiths were Medes and Egyptians. The men who wrought the wood, those were Sardians and Egyptians. The men who wrought the baked brick, those were Babylonians. The men who adorned the wall, those were Medes and Egyptians.[citation needed]

This was imperial art on a scale the world had not seen before. Materials and artists were drawn from all corners of the empire, and thus tastes, styles, and motifs became mixed together in an eclectic art and architecture that in itself mirrored the Persian empire.[citation needed]

Nishat Bagh in Srinagar, Kashmir (built during Mughal rule), a quintessential example of a Persian Garden with tree-lined avenues and flowing watercourses The legacy of the Persian garden throughout the Middle East and South Asia starts in the Achaemenid period, especially with the construction of Pasargadae by Cyrus the Great. In fact, the English word 'paradise' derives from the Greek parádeisos ' which ultimately comes from the Old Persian pairi-daêza', used to describe the walled gardens of ancient Persia. Distinct characteristics including flowing watercourses, fountains and water-channels, a structured orientational scheme (chahar-bagh) and a variety of flower and fruit-bearing trees brought from across the empire, all key features that served as a key inspiration for Islamic gardens ranging from Spain to India. The famous Alhambra complex in Spain (built by Andalusian Arabs), Safavid parks and boulevards at Isfahan and Mughal gardens of India and Pakistan (including those at the Taj Mahal) are all descendants of this cultural tradition.

Engineering innovations were required to maintain Persian gardens amid the aridity and difficulty of attaining fresh water in the Iranian plateau. Persepolis was the center of an empire that reached Greece and India, was supplied with water through underground channels called qanat, allowing maintenance of its gardens and palaces. These structures consist of deep vertical shafts into water reservoirs, followed by gently-sloping channels bringing fresh water from high-altitude aquifers to valleys and lowland plains. The influence of the qanat is widespread throughout the Middle East and Central Asia (including in Xinjiang region of Western China) due to its productivity and efficiency in arid environments. The acequias of southern Spain were brought by Arabs from Iraq and Persia to advance agriculture in the dry Mediterranean climate of Al-Andalus, and from there, were implemented in southwestern North America for irrigation during Spanish colonization of the Americas. The American wife of an Iranian diplomat, Florence Khanum, wrote of Tehran that :

"The air is the most marvellous I ever was in, in any city. Mountain air, so sweet, dry and "preserving", delicious and life-giving.' She told of running streams, and fresh water bubbling up in the gardens. (This omnipresence of water, which doubtless spread from Persia to Baghdad and from there to Spain during its Muslim days, has given Spanish many a water-word: aljibe, for example, is Persian jub, brook; cano or pipe, is Arabic qanat—reed, canal. Thus J. T. Shipley, Dictionary of Word Origins)."

Also supplemented by the qanat are yakhchal, 'ice-pit' structures that use the rapid passage of water to aerate and cool their inner chambers.

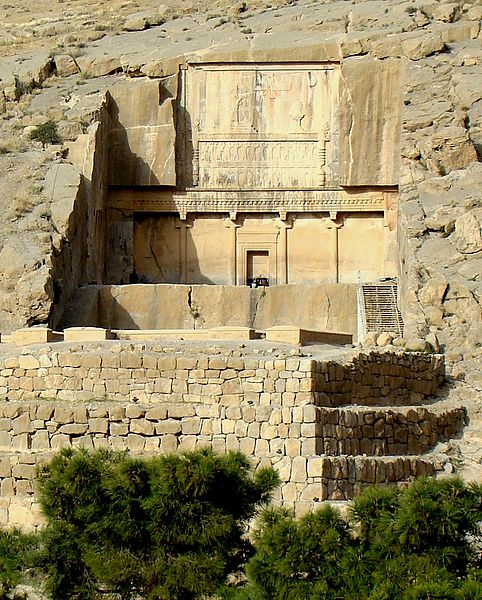

Tombs :

Tomb of Artaxerxes III in Persepolis Many Achaemenid rulers built tombs for themselves. The most famous, Naqsh-e Rustam, is an ancient necropolis located about 12 km north-west of Persepolis, with the tombs of four of the kings of the dynasty carved in this mountain: Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II. Other kings constructed their own tombs elsewhere. Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III preferred to carve their tombs beside their spring capital Persepolis, the left tomb belonging to Artaxerxes II and the right tomb belonging to Artaxerxes III, the last Achaemenid king to have a tomb. The tomb of the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty, Cyrus the Great, was built in Pasargadae (now a world heritage site).[citation needed]

Legacy :

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven wonders of the ancient world, was built by Greek architects for the local Persian satrap of Caria, Mausolus (Scale model) The Achaemenid Empire left a lasting impression on the heritage and cultural identity of Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, and influenced the development and structure of future empires. In fact, the Greeks, and later on the Romans, adopted the best features of the Persian method of governing an empire. The Persian model of governance was particularly formative in the expansion and maintenance of the Abbasid Caliphate, whose rule is widely considered the period of the 'Islamic Golden Age'. Like the ancient Persians, the Abbasid dynasty centered their vast empire in Mesopotamia (at the newly founded cities of Baghdad and Samarra, close to the historical site of Babylon), derived much of their support from Persian aristocracy and heavily incorporated the Persian language and architecture into Islamic culture (as opposed to the Greco-Roman influence on their rivals, the Umayyads of Spain). Historian Arnold Toynbee regarded Abassid society as a "reintegration" or "reincarnation" of Achaemenid society, as the synthesis of Persian, Turkic and Islamic modes of governance and knowledge allowed for the spread of Persianate culture over a wide swath of Eurasia through the Turkic-origin Seljuq, Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires. Historian Bernard Lewis wrote that "The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavor, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution. In a sense, Iranian Islam is a second advent of Islam itself, a new Islam sometimes referred to as Islam-i-Ajam.

It was this Persian Islam, rather than the original Arab Islam, that was brought to new areas and new peoples: to the Turks, first in Central Asia and then in the Middle East in the country which came to be called Turkey, and of course to India. The Ottoman Turks brought a form of Iranian civilization to the walls of Vienna. [...] By the time of the great Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century, Iranian Islam had become not only an important component; it had become a dominant element in Islam itself, and for several centuries the main centers of the Islamic power and civilization were in countries that were, if not Iranian, at least marked by Iranian civilization. . .The major centers of Islam in the late medieval and early modern periods, the centers of both political and cultural power, such as India, Central Asia, Iran, Turkey, were all part of this Iranian civilization."

Georg W. F. Hegel in his work The Philosophy of History introduces the Persian Empire as the "first empire that passed away" and its people as the "first historical people" in history. According to his account;

The

Persian Empire is an empire in the modern sense—like that

which existed in Germany, and the great imperial realm under the

sway of Napoleon; for we find it consisting of a number of states,

which are indeed dependent, but which have retained their own individuality,

their manners, and laws. The general enactments, binding upon all,

did not infringe upon their political and social idiosyncrasies,

but even protected and maintained them; so that each of the nations

that constitute the whole, had its own form of constitution. As

light illuminates everything—imparting to each object a peculiar

vitality—so the Persian Empire extends over a multitude of

nations, and leaves to each one its particular character. Some have

even kings of their own; each one its distinct language, arms, way

of life and customs. All this diversity coexists harmoniously under

the impartial dominion of Light ... a combination of peoples—leaving

each of them free. Thereby, a stop is put to that barbarism and

ferocity with which the nations had been wont to carry on their

destructive feuds.

Will Durant, the American historian and philosopher, during one of his speeches, "Persia in the History of Civilization", as an address before the Iran–America Society in Tehran on 21 April 1948, stated :

For

thousands of years Persians have been creating beauty. Sixteen centuries

before Christ there went from these regions or near it ... You have

been here a kind of watershed of civilization, pouring your blood

and thought and art and religion eastward and westward into the

world ... I need not rehearse for you again the achievements of

your Achaemenid period. Then for the first time in known history

an empire almost as extensive as the United States received an orderly

government, a competence of administration, a web of swift communications,

a security of movement by men and goods on majestic roads, equalled

before our time only by the zenith of Imperial Rome.

Attested :

There were 13 attested kings during the 220 years of the Achaemenid Empire's existence. The reign of Artaxerxes II was the longest, lasting 47 years.

Gallery :

Ruins of Throne Hall, Persepolis

Apadana Hall, Persian and Median soldiers at Persepolis

Lateral view of tomb of Cambyses II, Pasargadae, Iran

Plaque with horned lion-griffins. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.jpg)

_(14584070300).jpg)

.jpg)