| ARTIFICIAL CARANIAL DEFORMATION Artificial cranial deformation :

Portrait of Alchon Hun king Khingila, fom his coinage, circa 450 AD

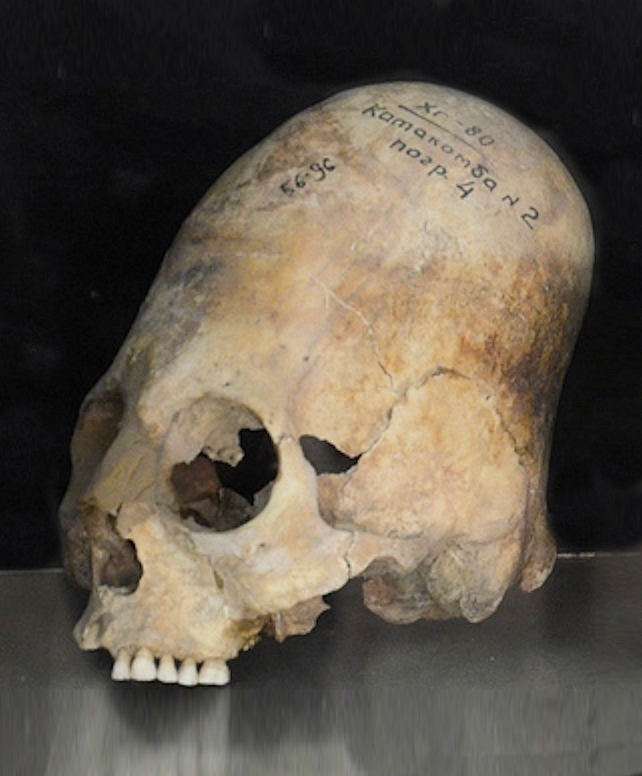

Elongated skull excavated in Samarkand (dated 600-800 AD), Afrasiab Museum of Samarkand Artificial cranial deformation or modification, head flattening, or head binding is a form of body alteration in which the skull of a human being is deformed intentionally. It is done by distorting the normal growth of a child's skull by applying force. Flat shapes, elongated ones (produced by binding between two pieces of wood), rounded ones (binding in cloth), and conical ones are among those chosen or valued in various cultures. Typically, the shape alteration is carried out on an infant, as the skull is most pliable at this time. In a typical case, headbinding begins approximately a month after birth and continues for about six months.

History :

The Iranian hero Rostam, mythical king of Zabulistan, in his 7th century AD mural at Panjikent. He is represented with an elongated skull, in the fashion of the Alchon Huns Intentional cranial deformation predates written history; it was practised commonly in a number of cultures that are widely separated geographically and chronologically, and still occurs today in a few areas, including Vanuatu.[citation needed]

The earliest suggested examples were once thought to include the Proto-Neolithic Homo sapiens component (ninth millennium BC) from Shanidar Cave in Iraq, and Neolithic peoples in Southwest Asia.

The earliest written record of cranial deformation—by Hippocrates, of the Macrocephali or Long-heads, who were named for their practice of cranial modification—dates to 400 BC.

Central

Asia :

The practice of cranial deformation was brought to Bactria and Sogdiana by the Yuezhi, a tribe that created the Kushan Empire. Men with such skulls are depicted in various surviving sculptures and friezes of that time, such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan.

The Alchon Huns are generally recognized by their elongated skull, a result of artificial skull deformation, which may have represented their "corporate identity". The elongated skulls appears clearly in most of the portaits of rulers in the coinage of the Alkhon Huns, and most visibly on the coinage of Khingila. These elongated skulls, which they obviously displayed with pride, distinguished them from other peoples, such as their predecessors the Kidarites. On their coins, the spectacular skulls came to replace the Sasanian-type crowns which had been current in the coinage of the region.

This practice is also known among other peoples of the steppes, particularly the Huns, as far as Europe.

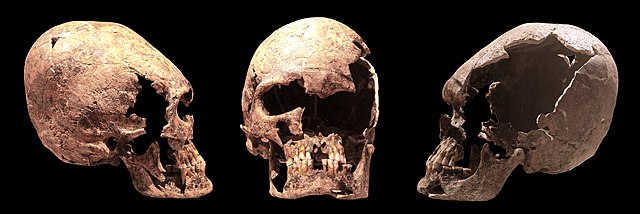

Elongated skull of a young woman, probably an Alan

Landesmuseum Württemberg deformed skull, early 6th century Allemannic culture

Deformed skulls, Afrasiab, Samarkand, Sogdia, 600 - 800 AD Americas

:

The practice of cranial deformation was also practiced by the Lucayan people of the Bahamas, and it was also known among the Aboriginal Australians.[citation needed]

Paracas skulls

Proto Nazca deformed skull, c 200–100 BC

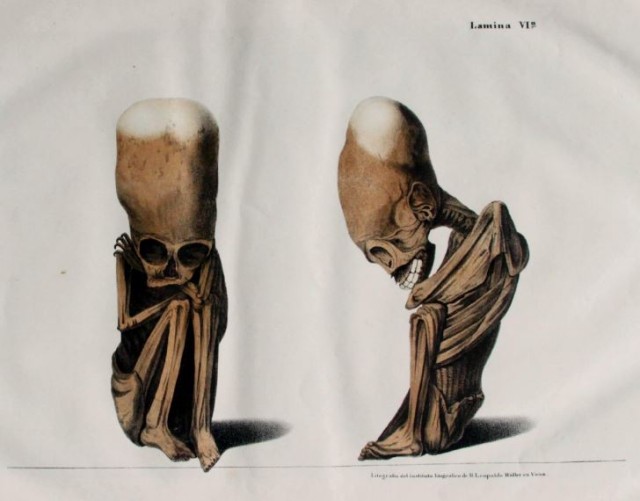

Dr. Leopold Müller: lithograph of a fetus in the intrauterine position with the typical Huanca skull shape, which was found in a mummy of a pregnant woman – (Lamina VI a.) in the Spanish version of the 'Peruvian Antiquities' (1851) Other regions :

Deliberate deformity of the skull, "Toulouse deformity", France. The band visible in photograph is used to induce shape change In Africa, the Mangbetu stood out to European explorers because of their elongated heads. Traditionally, babies' heads were wrapped tightly with cloth in order to give them this distinctive appearance. The practice began dying out in the 1950s.[citation needed]

Friedrich Ratzel reported in 1896 that deformation of the skull, both by flattening it behind and elongating it toward the vertex, was found in isolated instances in Tahiti, Samoa, Hawaii, and the Paumotu group, and that it occurred most frequently on Mallicollo in the New Hebrides (today Malakula, Vanuatu), where the skull was squeezed extraordinarily flat.

The custom of binding babies' heads in Europe in the twentieth century, though dying out at the time, was still extant in France, and also found in pockets in western Russia, the Caucasus, and in Scandinavia. The reasons for the shaping of the head varied over time and for different reasons, from aesthetic to pseudoscientific ideas about the brain's ability to hold certain types of thought depending on its shape. In the region of Toulouse (France), these cranial deformations persisted sporadically up until the early twentieth century; however, rather than being intentionally produced as with some earlier European cultures, Toulousian Deformation seemed to have been the unwanted result of an ancient medical practice among the French peasantry known as bandeau, in which a baby's head was tightly wrapped and padded in order to protect it from impact and accident shortly after birth. In fact, many of the early modern observers of the deformation were recorded as pitying these peasant children, whom they believed to have been lowered in intelligence due to the persistence of old European customs.

Methods

and types :

There is no broadly established classification system of cranial deformations, and many scientists have developed their own classification systems without agreeing on a single system for all forms observed. An example of an individual system is that of E. V. Zhirov, who described three main types of artificial cranial deformation—round, fronto-occipital, and sagittal—for occurrences in Europe and Asia, in the 1940s.

Various methods used by the Mayan people to shape a child's head

Painting by Paul Kane, showing a Chinookan child in the process of having its head flattened, and an adult after the process

An anatomical illustration from the 1921 German edition of Anatomie des Menschen: ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte with Latin terminology Motivations

and theories :

Historically, there have been a number of various theories regarding the motivations for these practices.

Lithographs of skulls by J. Basire It has also been considered possible that the practice of cranial deformation originates from an attempt to emulate those groups of the population in which elongated head shape was a natural condition. The skulls of some Ancient Egyptians are among those identified as often being elongated naturally and macrocephaly may be a familial characteristic. For example, Rivero and Tschudi describe a mummy containing a foetus with an elongated skull, describing it thus:

the same formation [i.e. absence of the signs of artificial pressure] of the head presents itself in children yet unborn; and of this truth we have had convincing proof in the sight of a foetus, enclosed in the womb of a mummy of a pregnant woman, which we found in a cave of Huichay, two leagues from Tarma, and which is, at this moment, in our collection. Professor D'Outrepont, of great Celebrity in the department of obstetrics, has assured us that the foetus is one of seven months' age. It belongs, according to a very clearly defined formation of the cranium, to the tribe of the Huancas. We present the reader with a drawing of this conclusive and interesting proof in opposition to the advocates of mechanical action as the sole and exclusive cause of the phrenological form of the Peruvian race.

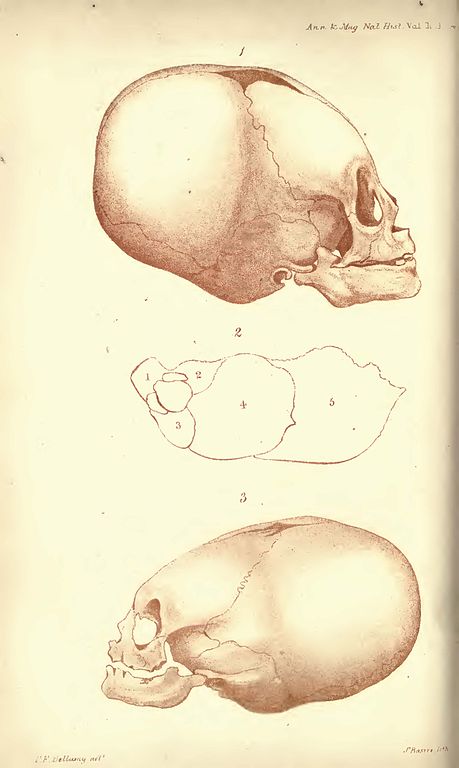

P. F. Bellamy makes a similar observation about the two elongated skulls of infants, which were discovered and brought to England by a "Captain Blankley" and handed over to the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society in 1838. According to Bellamy, these skulls belonged to two infants, female and male, "one of which was not more than a few months old, and the other could not be much more than one year." He writes,

It will be manifest from the general contour of these skulls that they are allied to those in the Museum of the College of Surgeons in London, denominated Titicacans. Those adult skulls are very generally considered to be distorted by the effects of pressure; but in opposition to this opinion Dr. Graves has stated that "a careful examination of them has convinced him that their peculiar shape cannot be owing to artificial pressure;" and to corroborate this view, we may remark that the peculiarities are as great in the child as in the adult, and indeed more in the younger than in the elder of the two specimens now produced: and the position is considerably strengthened by the great relative length of the large bones of the cranium; by the direction of the plane of the occipital bone, which is not forced upwards, but occupies a place in the under part of the skull; by the further absence of marks of pressure, there being no elevation of the vertex nor projection of either side; and by the fact of there being no instrument nor mechanical contrivance suited to produce such an alteration of form (as these skulls present) found in connexion with them.

Health

effects :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)