| MEDIAN / MEDES

A map of the Median Empire at its greatest extent (6th century BC), according to Herodotus Median Dynasty

Madai

c. 678 BC - c. 549 BC

Capital : Ecbatana

Common languages : Median

Religion : Ancient Iranian religion (related to Mithraism, early Zoroastrianism)

King

Historical era : Iron Age

• Established : c. 678 BC

• Conquered by Cyrus the Great : c. 549 BC

Area

585 BC : 2,800,000 km2 (1,100,000 sq mi)

Preceded by

Neo-Assyrian Empire

Urartu

Succeeded by

Achaemenid Empire

The Medes (Old Persian Mada-, Hebrew: Madai) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the mountainous region of northwestern Iran and the northeastern and eastern region of Mesopotamia located in the region of Hamadan (Ecbatana). Their emergence in Iran is believed to have occurred during the 8th century BC. In the 7th century BC, all of western Iran and some other territories were under Median rule, but their precise geographic extent remains unknown.

Although they are generally recognized as having an important place in the history of the ancient Near East, the Medes have left no textual source to reconstruct their history, which is known only from outside sources such as the Assyrians, Babylonians and Greeks, as well as a few Iranian archaeological sites, which are believed to have been occupied by Medes. The accounts relating to the Medes reported by Herodotus have left the image of a powerful people, who would have formed an empire at the beginning of the 7th century BC that lasted until the 550s BC, played a determining role in the fall of the Assyrian Empire and competed with the powerful kingdoms of Lydia and Babylonia. However, a recent reassessment of contemporary sources from the Mede period has altered scholars' perceptions of the Median state. The state remains difficult to perceive in the documentation, which leaves many doubts about it, some specialists even suggesting that there never was a powerful Median kingdom. In any case, it appears that after the fall of the last Median king against Cyrus the Great of the Persian Empire, Media became an important province and prized by the empires which successively dominated it (Achaemenids, Seleucids, Parthians and Sasanids).

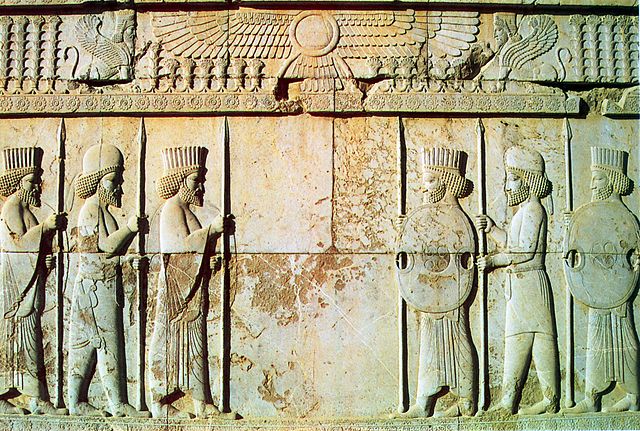

The Apadana Palace, 5th century BC Achaemenid bas-relief shows a Mede soldier behind a Persian soldier, in Persepolis, Iran Tribes

:

Thus Deioces collected the Medes into a nation, and ruled over them alone. Now these are the tribes of which they consist: the Busae, the Paretaceni, the Struchates, the Arizanti, the Budii, and the Magi.

The six Median tribes resided in Media proper, the triangular area between Rhagae, Aspadana and Ecbatana. In present-day Iran, that is the area between Tehran, Isfahan and Hamadan, respectively. Of the Median tribes, the Magi resided in Rhagae, modern Tehran. They were of a sacred caste which ministered to the spiritual needs of the Medes. The Paretaceni tribe resided in and around Aspadana, modern Isfahan, the Arizanti lived in and around Kashan (Isfahan Province), and the Busae tribe lived in and around the future Median capital of Ecbatana, near modern Hamadan. The Struchates and the Budii lived in villages in the Median triangle.

Etymology

:

Greek scholars during antiquity would base ethnological conclusions on Greek legends and the similarity of names. According to the Histories of Herodotus (440 BC) :

The Medes were formerly called by everyone Arians, but when the Colchian woman Medea came from Athens to the Arians, they changed their name, like the Persians [did after Perses, son of Perseus and Andromeda]. This is the Medes' own account of themselves.

Mythology

:

Archaeology :

Excavation from ancient Ecbatana, Hamadan, Iran The discoveries of Median sites in Iran happened only after the 1960s. For 1960 the search for Median archeological sources has mostly focused in an area known as the "Median triangle", defined roughly as the region bounded by Hamadan and Malayer (in Hamadan Province) and Kangavar (in Kermanshah Province). Three major sites from central western Iran in the Iron Age III period (i.e. 850–500 BC) are :

•

Tepe Nush-i Jan (a primarily religious site of Median period),

The materials found at Tepe Nush-i Jan, Godin Tepe, and other sites located in Media together with the Assyrian reliefs show the existence of urban settlements in Media in the first half of the 1st millennium BC which had functioned as centres for the production of handicrafts and also of an agricultural and cattle-breeding economy of a secondary type. For other historical documentation, the archaeological evidence, though rare, together with cuneiform records by Assyrian make it possible, regardless of Herodotus' accounts, to establish some of the early history of Medians.

Geography

:

Its borders were limited in the north by the non-Iranian states of Gizilbunda and Mannea, and to its south by Ellipi and Elam. Gizilbunda was located in the Qaflankuh Mountains, and Ellipi was located in the south of modern Lorestan Province. On the east and southeast of Media, as described by the Assyrians, another land with the name of "Patušarra" appears. This land was located near a mountain range which the Assyrians call "Bikni" and describe as "Lapis Lazuli Mountain". There are differing opinions on the location of this mountain. Mount Damavand of Tehran and Alvand of Hamadan are two proposed sites. This location is the most remote eastern area that the Assyrians knew of or reached during their expansion until the beginning of the 7th century BC.

In Achaemenid sources, specifically from the Behistun Inscription (2.76, 77–78), the capital of Media is Ecbatana, called "Hamgmatana-" in Old Persian (Elamite:Agmadana-; Babylonian: Agamtanu-) corresponding to modern-day Hamadan.

The other cities existing in Media were Laodicea (modern Nahavand) and the mound that was the largest city of the Medes, Rhages (present-day Rey). The fourth city of Media was Apamea, near Ecbatana, whose precise location is now unknown. In later periods, Medes and especially Mede soldiers are identified and portrayed prominently in ancient archaeological sites such as Persepolis, where they are shown to have a major role and presence in the military of the Achaemenid Empire.

History

:

Timeline of Pre-Achaemenid era At the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Iranian tribes emerged in the region of northwest Iran. These tribes expanded their control over larger areas. Subsequently, the boundaries of Media changed over a period of several hundred years. Iranian tribes were present in western and northwestern Iran from at least the 12th or 11th centuries BC. But the significance of Iranian elements in these regions were established from the beginning of the second half of the 8th century BC. By this time the Iranian tribes were the majority in what later become the territory of the Median Kingdom and also the west of Media proper. A study of textual sources from the region shows that in the Neo-Assyrian period, the regions of Media, and further to the west and the northwest, had a population with Iranian speaking people as the majority.

This period of migration coincided with a power vacuum in the Near East with the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC), which had dominated northwestern Iran and eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus, going into a comparative decline. This allowed new peoples to pass through and settle. In addition Elam, the dominant power in Iran, was suffering a period of severe weakness, as was Babylonia to the west.

In western and northwestern Iran and in areas further west prior to Median rule, there is evidence of the earlier political activity of the powerful societies of Elam, Mannaea, Assyria and Urartu. There are various and up-dated opinions on the positions and activities of Iranian tribes in these societies and prior to the "major Iranian state formations" in the late 7th century BC. One opinion (of Herzfeld, et al.) is that the ruling class were "Iranian migrants" but the society was "autonomous" while another opinion (of Grantovsky, et al.) holds that both the ruling class and basic elements of the population were Iranian.

Rhyton in the shape of a ram's head, gold – western Iran – Median, late 7th–early 6th century BC

The neighboring Neo-Babylonian Empire at its greatest extent after the destruction of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

Protoma in the form of a bull's head, 8th century BC, gold and filigree, National Museum, Warsaw

Rise and fall :

During the reign of Sinsharishkun (622–612 BC), the Assyrian empire, which had been in a state of constant civil war since 626 BC, began to unravel. Subject peoples, such as the Medes, Babylonians, Chaldeans, Egyptians, Scythians, Cimmerians, Lydians and Arameans quietly ceased to pay tribute to Assyria.

Neo-Assyrian dominance over the Medians came to an end during the reign of Median King Cyaxares, who, in alliance with King Nabopolassar of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, attacked and destroyed the strife-riven Neo-Assyrian empire between 616 and 609 BC. The newfound alliance helped the Medes to capture Nineveh in 612 BC, which resulted in the eventual collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by 609 BC. The Medes were subsequently able to establish their Median Kingdom (with Ecbatana as their royal capital) beyond their original homeland and had eventually a territory stretching roughly from northeastern Iran to the Kizilirmak River in Anatolia. After the fall of Assyria between 616 BC and 609 BC, a unified Median state was formed, which together with Babylonia, Lydia, and ancient Egypt became one of the four major powers of the ancient Near East.

Cyaxares was succeeded by his son King Astyages. In 553 BC, his maternal grandson Cyrus the Great, the King of Anshan/Persia, a Median vassal, revolted against Astyages. In 550 BC, Cyrus finally won a decisive victory resulting in Astyages' capture by his own dissatisfied nobles, who promptly turned him over to the triumphant Cyrus. After Cyrus's victory against Astyages, the Medes were subjected to their close kin, the Persians. In the new empire they retained a prominent position; in honour and war, they stood next to the Persians; their court ceremony was adopted by the new sovereigns, who in the summer months resided in Ecbatana; and many noble Medes were employed as officials, satraps and generals.

Median

dynasty :

•

Deioces (700–647 BC)

In Herodotus (book 1, chapters 95–130), Deioces is introduced as the founder of a centralised Median state. He had been known to the Median people as "a just and incorruptible man" and when asked by the Median people to solve their possible disputes he agreed and put forward the condition that they make him "king" and build a great city at Ecbatana as the capital of the Median state. Judging from the contemporary sources of the region and disregarding the account of Herodotus puts the formation of a unified Median state during the reign of Cyaxares or later.

Culture

and society :

Language

:

No original deciphered text has been proven to have been written in the Median language. It is suggested that similar to the later Iranian practice of keeping archives of written documents in Achaemenid Iran, there was also a maintenance of archives by the Median government in their capital Ecbatana. There are examples of "Median literature" found in later records. One is according to Herodotus that the Median king Deioces, appearing as a judge, made judgement on causes submitted in writing. There is also a report by Dinon on the existence of "Median court poets". Median literature is part of the "Old Iranian literature" (including also Saka, Old Persian, Avestan) as this Iranian affiliation of them is explicit also in ancient texts, such as Herodotus's account that many peoples including Medes were "universally called Iranian".

Words of Median origin appear in various other Iranian dialects, including Old Persian. A feature of Old Persian inscriptions is the large number of words and names from other languages and the Median language takes in this regard a special place for historical reasons. The Median words in Old Persian texts, whose Median origin can be established by "phonetic criteria", appear "more frequently among royal titles and among terms of the chancellery, military, and judicial affairs". Words of Median origin include :

The Ganj Nameh ("treasure epistle") in Ecbatana. The inscriptions are by Darius I and his son Xerxes I

• *cira- : "origin". The word appears

in *cirabzana- (med.) "exalting his linage", *ciramira-

(med.) "having mithraic origin", *ciraspata- (med.) "having

a brilliant army", etc.

Apadana Hall, 5th century BC Achaemenid-era carving of Persian and Median soldiers in traditional costume (Medians are wearing rounded hats and boots), in Persepolis, Iran There are very limited sources concerning the religion of Median people. Primary sources pointing to religious affiliations of Medes found so far include the archaeological discoveries in Tepe Nush-e Jan, personal names of Median individuals, and the Histories of Herodotus. The archaeological source gives the earliest of the temple structures in Iran and the "stepped fire altar" discovered there is linked to the common Iranian legacy of the "cult of fire". Herodotus mentions Median Magi as a Median tribe providing priests for both the Medes and the Persians. They had a "priestly caste" which passed their functions from father to son. They played a significant role in the court of the Median king Astyages who had in his court certain Medians as "advisers, dream interpreters, and soothsayers".

Classical historians "unanimously" regarded the Magi as priests of the Zoroastrian faith. From the personal names of Medes as recorded by Assyrians (in 8th and 9th centuries BC) there are examples of the use of the Indo-Iranian word arta- (lit. "truth") which is familiar from both Avestan and Old Persian and also examples of theophoric names containing Maždakku and also the name "Ahura Mazda". Scholars disagree whether these are indications of Zoroastrian religion amongst the Medes. Diakonoff believes that "Astyages and perhaps even Cyaxares had already embraced a religion derived from the teachings of Zoroaster" and Mary Boyce believes that "the existence of the Magi in Media with their own traditions and forms of worship was an obstacle to Zoroastrian proselytizing there". Boyce wrote that the Zoroastrian traditions in the Median city of Ray probably goes back to the 8th century BC. It is suggested that from the 8th century BC, a form of "Mazdaism with common Iranian traditions" existed in Media and the strict reforms of Zarathustra began to spread in western Iran during the reign of the last Median kings in the 6th century BC.

It has also been suggested [by whom?] that Mithra is a Median name and Medes may have practised Mithraism and had Mithra as their supreme deity.

Kurds

and Medes :

"Though some Kurdish intellectuals claim that their people are descended from the Medes, there is no evidence to permit such a connection across the considerable gap in time between the political dominance of the Medes and the first attestation of the Kurds" - van Bruinessen.

Contemporary linguistic evidence has challenged the previously suggested view that the Kurds are descendants of the Medes. Gernot Windfuhr, professor of Iranian Studies, identified the Kurdish languages as Parthian, albeit with a Median substratum. David Neil MacKenzie, an authority on the Kurdish language, said Kurdish was closer to Persian and questioned the "traditional" view holding that Kurdish, because of its differences from Persian, should be regarded as a Northwestern Iranian language. Garnik Asatrian stated that "The Central Iranian dialects, and primarily those of the Kashan area in the first place, as well as the Azari dialects (otherwise called Southern Tati) are probably the only Iranian dialects, which can pretend to be the direct offshoots of Median... In general, the relationship between Kurdish and Median is not closer than the affinities between the latter and other North Western dialects – Baluchi, Talishi, South Caspian, Zaza, Gurani, Kurdish (Soranî, Kurmancî, Kelhorî) Asatrian also stated that "there is no serious ground to suggest a special genetic affinity within North-Western Iranian between this ancient language [Median] and Kurdish. The latter does not share even the generally ephemeric peculiarity of Median."

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_Relief_Achamenid_Period.jpg)