| PERSEPOLIS

Persepolis, Iran

Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis Parsa (Old Persian)

Takht-e Jamshid (Persian)

Location : Marvdasht, Fars Province, Iran

Coordinates : 29°56′04″N 52°53′29″E

Type : Settlement

History

Builder : Darius the Great, Xerxes the Great and Artaxerxes I

Material : Limestone, mud-brick, cedar wood

Founded : 6th century BC

Periods : Achaemenid Empire

Cultures : Persian

Events : Battle of the Persian Gates, Macedonian sack of Persepolis, Nowruz and The 2,500 Year Celebration of the Persian Empire

Site notes

Condition : in ruins

Management : Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Iran

Public access : open

Architecture

Architectural styles : Achaemenid

UNESCO World Heritage Site

Official name : Persepolis

Type : Cultural

Criteria : i, iii, vi

Designated : 1979 (3rd session)

Reference no. : 114

State Party : Iran

Region : Asia-Pacific

Persepolis (Old Persian: Parsa) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550–330 BC). It is situated 60 kilometres (37 mi) northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars Province, Iran. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Name

:

An inscription left in AD 311 by Sasanian prince Shapur Sakanshah, the son of Hormizd II, refers to the site as Sad-stun, meaning "Hundred Pillars". Because medieval Persians attributed the site to Jamshid, a king from Iranian mythology, it has been referred to as Takht-e-Jamshid (Persian: Taxt e Jamšid, literally meaning "Throne of Jamshid". Another name given to the site in the medieval period was Cehel Menar, literally meaning "Forty Minarets".

Geography

:

As is typical of Achaemenid cities, Persepolis was built on a (partially) artificial platform The site includes a 125,000 square meter terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Rahmat Mountain. The other three sides are formed by retaining walls, which vary in height with the slope of the ground. Rising from 5–13 metres (16–43 feet) on the west side was a double stair. From there, it gently slopes to the top. To create the level terrace, depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks, which were joined together with metal clips.

History :

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. André Godard, the French archaeologist who excavated Persepolis in the early 1930s, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site of Persepolis, but that it was Darius I who built the terrace and the palaces. Inscriptions on these buildings support the belief that they were constructed by Darius.

With Darius I, the scepter passed to a new branch of the royal house. Persepolis probably became the capital of Persia proper during his reign. However, the city's location in a remote and mountainous region made it an inconvenient residence for the rulers of the empire. The country's true capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This may be why the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until Alexander the Great took and plundered it.

General view of the ruins of Persepolis

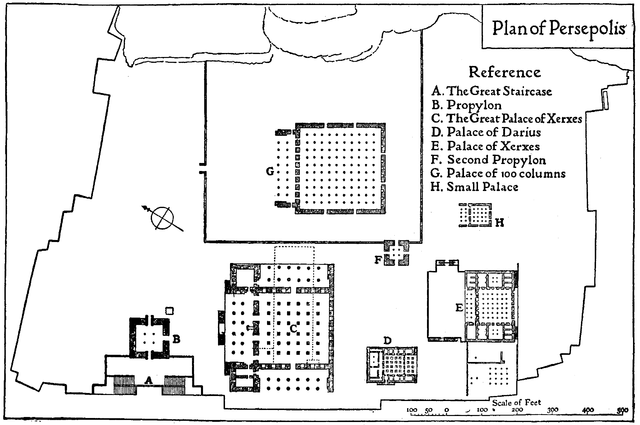

Aerial architectural plan of Persepolis Darius I's construction of Persepolis were carried out parallel to those of the Palace of Susa. According to Gene R. Garthwaite, the Susa Palace served as Darius' model for Persepolis. Darius I ordered the construction of the Apadana and the Council Hall (Tripylon or the "Triple Gate"), as well as the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings. These were completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings on the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the Greek historian Ctesias mentioned that Darius I's grave was in a cliff face that could be reached with an apparatus of ropes.

Around 519 BC, construction of a broad stairway was begun. The stairway was initially planned to be the main entrance to the terrace 20 metres (66 feet) above the ground. The dual stairway, known as the Persepolitan Stairway, was built symmetrically on the western side of the Great Wall. The 111 steps measured 6.9 metres (23 feet) wide, with treads of 31 centimetres (12 inches) and rises of 10 centimetres (3.9 inches). Originally, the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback. New theories, however, suggest that the shallow risers allowed visiting dignitaries to maintain a regal appearance while ascending. The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the north-eastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of All Nations.

Grey limestone was the main building material used at Persepolis. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, the terrace was prepared. Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated water storage tank was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain. Professor Olmstead suggested the cistern was constructed at the same time that construction of the towers began.

The uneven plan of the terrace, including the foundation, acted like a castle, whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front. Diodorus Siculus writes that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, which all had towers to provide a protected space for the defense personnel. The first wall was 7 metres (23 feet) tall, the second, 14 metres (46 feet) and the third wall, which covered all four sides, was 27 metres (89 feet) in height, though no presence of the wall exists in modern times.

Function

:

Destruction

:

"The Burning of Persepolis", 1890, by Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse Around that time, a fire burned "the palaces" or "the palace". Scholars agree that this event, described in historic sources, occurred at the ruins that have been now re-identified as Persepolis. From Stolze's investigations, it appears that at least one of these, the castle built by Xerxes I, bears traces of having been destroyed by fire. The locality described by Diodorus Siculus after Cleitarchus corresponds in important particulars with the historic Persepolis, for example, in being supported by the mountain on the east.

It is believed that the fire which destroyed Persepolis started from Hadish Palace, which was the living quarters of Xerxes I, and spread to the rest of the city. It is not clear if the fire was an accident or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the second Persian invasion of Greece. Many historians argue that, while Alexander's army celebrated with a symposium, they decided to take revenge against the Persians. If that is so, then the destruction of Persepolis could be both an accident and a case of revenge.

The Book of Arda Wiraz, a Zoroastrian work composed in the 3rd or 4th century, describes Persepolis' archives as containing "all the Avesta and Zend, written upon prepared cow-skins, and with gold ink", which were destroyed. Indeed, in his Chronology of the Ancient Nations, the native Iranian writer Biruni indicates unavailability of certain native Iranian historiographical sources in the post-Achaemenid era, especially during the Parthian Empire. He adds: " [Alexander] burned the whole of Persepolis as revenge to the Persians, because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years ago. People say that, even at the present time, the traces of fire are visible in some places."

Paradoxically, the event that caused the destruction of these texts may have helped in the preservation of the Persepolis Administrative Archives, which might otherwise have been lost over time to natural and man-made events. According to archaeological evidence, the partial burning of Persepolis did not affect what are now referred to as the Persepolis Fortification Archive tablets, but rather may have caused the eventual collapse of the upper part of the northern fortification wall that preserved the tablets until their recovery by the Oriental Institute's archaeologists.

A general view of Persepolis After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire :

Ruins of the Western side of the compound at Persepolis In 316 BC, Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire (see Diod. xix, 21 seq., 46; probably after Hieronymus of Cardia, who was living about 326). The city must have gradually declined in the course of time. The lower city at the foot of the imperial city might have survived for a longer time; but the ruins of the Achaemenids remained as a witness to its ancient glory. It is probable that the principal town of the country, or at least of the district, was always in this neighborhood.

About 200 BC, the city of Estakhr, five kilometers north of Persepolis, was the seat of the local governors. From there, the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and there Estakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sasanian kings have covered the face of the rocks in this neighborhood, and in part even the Achaemenid ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions. They must themselves have been built largely there, although never on the same scale of magnificence as their ancient predecessors. The Romans knew as little about Estakhr as the Greeks had known about Persepolis, despite the fact that the Sasanians maintained relations for four hundred years, friendly or hostile, with the empire.

At the time of the Muslim invasion of Persia, Estakhr offered a desperate resistance. It was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis of Shiraz. In the 10th century, Estakhr dwindled to insignificance, as seen from the descriptions of Estakhri, a native (c. 950), and of Al-Muqaddasi (c. 985). During the following centuries, Estakhr gradually declined, until it ceased to exist as a city.

Archaeological

research :

In 1618, García de Silva Figueroa, King Philip III of Spain's ambassador to the court of Abbas I, the Safavid monarch, was the first Western traveler to link the site known in Iran as "Chehel Minar" as the site known from Classical authors as Persepolis.

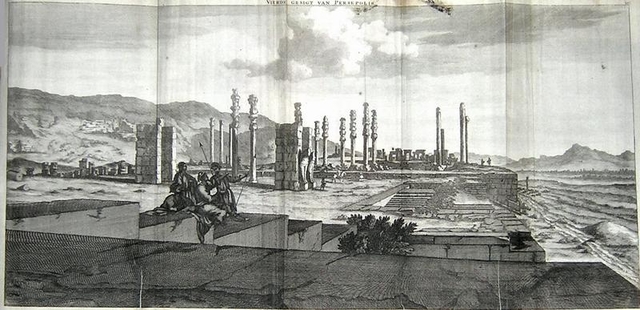

Pietro Della Valle visited Persepolis in 1621, and noticed that only 25 of the 72 original columns were still standing, due to either vandalism or natural processes. The Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruijn visited Persepolis in 1704.

Sketch of Persepolis from 1704 by Cornelis de Bruijn

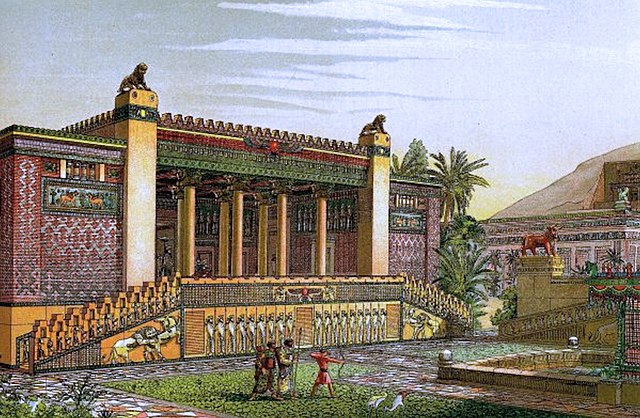

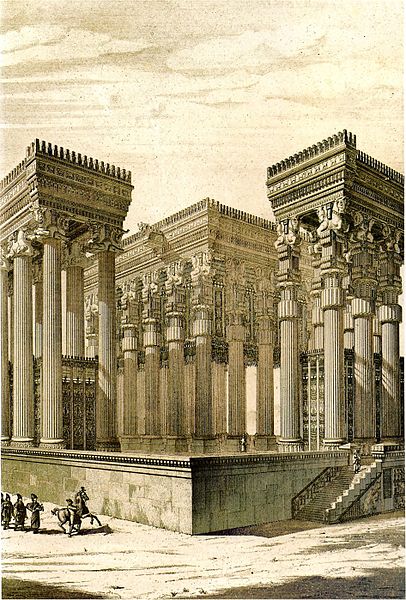

Drawing of Persepolis in 1713 by Gérard Jean-Baptiste

Drawing of the Tachara by Charles Chipiez

The Apadana by Charles Chipiez

Apadana detail by Charles Chipiez The fruitful region was covered with villages until its frightful devastation in the 18th century; and even now it is, comparatively speaking, well cultivated. The Castle of Estakhr played a conspicuous part as a strong fortress, several times, during the Muslim period. It was the middlemost and the highest of the three steep crags which rise from the valley of the Kur, at some distance to the west or northwest of the necropolis of Naqsh-e Rustam.

The French voyagers Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste are among the first to provide not only a literary review of the structure of Persepolis, but also to create some of the best and earliest visual depictions of its structure. In their publications in Paris, in 1881 and 1882, titled Voyages en Perse de MM. Eugene Flanin peintre et Pascal Coste architecte, the authors provided some 350 ground breaking illustrations of Persepolis. French influence and interest in Persia's archaeological findings continued after the accession of Reza Shah, when André Godard became the first director of the archeological service of Iran.

In the 1800s, a variety of amateur digging occurred at the site, in some cases on a large scale.

The first scientific excavations at Persepolis were carried out by Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt representing the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. They conducted excavations for eight seasons, beginning in 1930, and included other nearby sites.

Achaemenid frieze designs at Persepolis Herzfeld believed that the reasons behind the construction of Persepolis were the need for a majestic atmosphere, a symbol for the empire, and to celebrate special events, especially the Nowruz. For historical reasons, Persepolis was built where the Achaemenid dynasty was founded, although it was not the center of the empire at that time.

Excavations of plaque fragments hint at a scene with a contest between Herakles and Apollo, dubbed A Greek painting at Persepolis.

Architecture

:

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include the Great Stairway, the Gate of All Nations, the Apadana, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and the Tachara, the Hadish Palace, the Palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House.

Ruins and remains :

Reliefs of lotus flowers are frequently used on the walls and monuments at Persepolis Ruins of a number of colossal buildings exist on the terrace. All are constructed of dark-grey marble. Fifteen of their pillars stand intact. Three more pillars have been re-erected since 1970. Several of the buildings were never finished. F. Stolze has shown that some of the mason's rubbish remains.

So far, more than 30,000 inscriptions have been found from the exploration of Persepolis, which are small and concise in terms of size and text, but they are the most valuable documents of the Achaemenid period. Based on these inscriptions that are currently held in the United States most of the time indicate that during the time of Persepolis, wage earners were paid.

Since the time of Pietro Della Valle, it has been beyond dispute that these ruins represent the Persepolis captured and partly destroyed by Alexander the Great.

Behind the compound at Persepolis, there are three sepulchers hewn out of the rock in the hillside. The facades, one of which is incomplete, are richly decorated with reliefs. About 13 km NNE, on the opposite side of the Pulvar River, rises a perpendicular wall of rock, in which four similar tombs are cut at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. Modern-day Iranians call this place Naqsh-e Rustam ("Rustam Relief"), from the Sasanian reliefs beneath the opening, which they take to be a representation of the mythical hero Rostam. It may be inferred from the sculptures that the occupants of these seven tombs were kings. An inscription on one of the tombs declares it to be that of Darius I, concerning whom Ctesias relates that his grave was in the face of a rock, and could only be reached by the use of ropes. Ctesias mentions further, with regard to a number of Persian kings, either that their remains were brought "to the Persians," or that they died there.

A bas-relief at Persepolis, representing a symbol in Zoroastrianism for Nowruz

A bas-relief from the Apadana depicting Delegations including Lydians and Armenians bringing their famous wine to the king

Achaemenid plaque from Persepolis, kept at the National Museum, Tehran

Relief of a Median man at Persepolis

Objects from Persepolis kept at the National Museum, Tehran Gate

of All Nations :

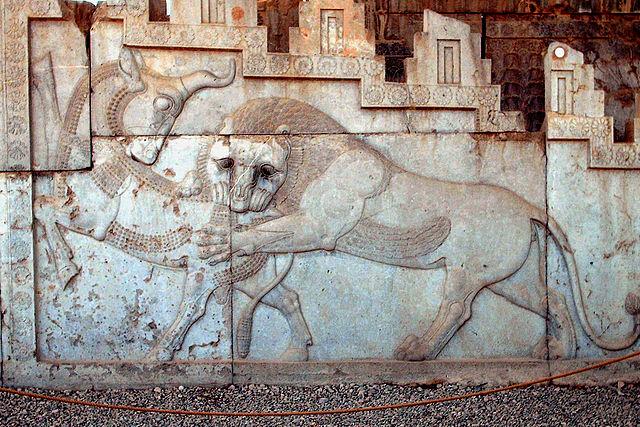

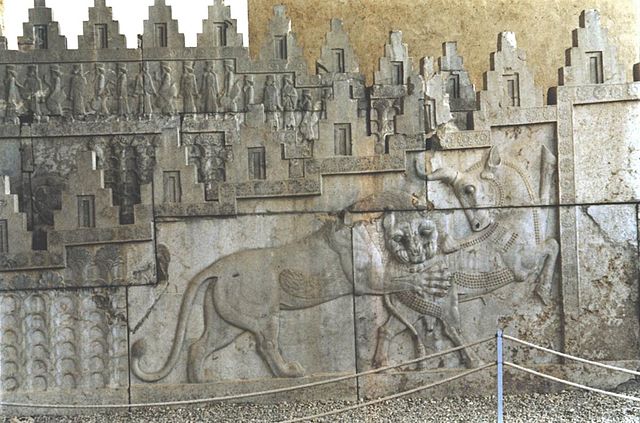

A pair of lamassus, bulls with the heads of bearded men, stand by the western threshold. Another pair, with wings and a Persian Head (Gopät-Shäh), stands by the eastern entrance, to reflect the power of the empire.

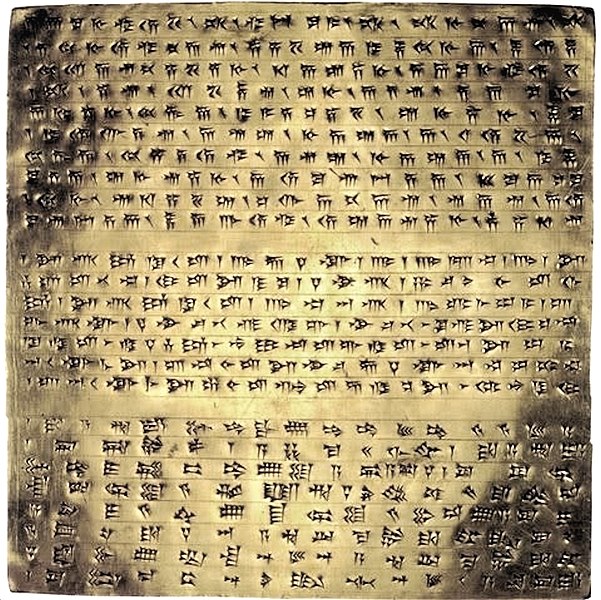

The name of Xerxes I was written in three languages and carved on the entrances, informing everyone that he ordered it to be built.

A lamassu at the Gate of All Nations

Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis

The Great Double Staircase at Persepolis

Bas-relief on the staircase of the palace The Apadana Palace :

Statue of a Persian Mastiff found at the Apadana, kept at the National Museum, Tehran Darius I built the greatest palace at Persepolis on the western side of platform. This palace was called the Apadana. The King of Kings used it for official audiences. The work began in 518 BC, and his son, Xerxes I, completed it 30 years later. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60 metres (200 ft) long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Each column is 19 metres (62 ft) high with a square Taurus (bull) and plinth. The columns carried the weight of the vast and heavy ceiling. The tops of the columns were made from animal sculptures such as two-headed lions, eagles, human beings and cows (cows were symbols of fertility and abundance in ancient Iran). The columns were joined to each other with the help of oak and cedar beams, which were brought from Lebanon. The walls were covered with a layer of mud and stucco to a depth of 5 cm, which was used for bonding, and then covered with the greenish stucco which is found throughout the palaces.

Foundation tablets of gold and silver were found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the Palace. They contained an inscription by Darius in Old Persian cuneiform, which describes the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms, and is known as the DPh inscription :

Gold foundation tablets of Darius I for the Apadana Palace, in their original stone box. The Apadana coin hoard had been deposited underneath. Circa 510 BC

One of the two gold deposition plates. Two more were in silver. They all had the same trilingual inscription (DPh inscription) Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid. King Darius says: This is the kingdom which I hold, from the Sacae who are beyond Sogdia, to Kush, and from Sind (Old Persian: "Hidauv", locative of "Hiduš", i.e. "Indus valley") to Lydia (Old Persian: "Spardâ") - [this is] what Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods, bestowed upon me. May Ahuramazda protect me and my royal house!

—

DPh inscription of Darius I in the foundations of the Apadana Palace

The walls were tiled and decorated with pictures of lions, bulls, and flowers. Darius ordered his name and the details of his empire to be written in gold and silver on plates, which were placed in covered stone boxes in the foundations under the Four Corners of the palace. Two Persepolitan style symmetrical stairways were built on the northern and eastern sides of Apadana to compensate for a difference in level. Two other stairways stood in the middle of the building. The external front views of the palace were embossed with carvings of the Immortals, the Kings' elite guards. The northern stairway was completed during the reign of Darius I, but the other stairway was completed much later.

The reliefs on the staircases allow one to observe the people from across the empire in their traditional dress, and even the king himself, "down to the smallest detail".

Ruins of the Apadana, Persepolis

Depiction of united Medes and Persians at the Apadana, Persepolis

Ruins of the Apadana's columns

Depiction of trees and lotus flowers at the Apadana, Persepolis

Depiction of figures at the Apadana Apadana

Palace coin hoard :

Gold Croeseid minted in the time of Darius, of the type of the eight Croeseids found in the Apadana hoard, circa 545-520 BCE. Light series: 8.07 grams, Sardis mint

Type of the Aegina stater found in the Apadana hoard, 550–530 BCE. Obv: Sea turtle with large pellets down centre. Rev: incuse square punch with eight sections

Type of the Abdera coin found in the Apadana hoard, circa 540/35-520/15 BCE. Obv: Griffin seated left, raising paw. Rev: Quadripartite incuse square The Apadana hoard is a hoard of coins that were discovered under the stone boxes containing the foundation tablets of the Apadana Palace in Persepolis. The coins were discovered in excavations in 1933 by Erich Schmidt, in two deposits, each deposit under the two deposition boxes that were found. The deposition of this hoard is dated to circa 515 BCE. The coins consisted in eight gold lightweight Croeseids, a tetradrachm of Abdera, a stater of Aegina and three double-sigloi from Cyprus. The Croeseids were found in very fresh condition, confirming that they had been recently minted under Achaemenid rule. The deposit did not have any Darics and Sigloi, which also suggests strongly that these coins typical of Achaemenid coinage only started to be minted later, after the foundation of the Apadana Palace.

The

Throne Hall :

At the beginning of the reign of Xerxes I, the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for military commanders and representatives of all the subject nations of the empire. Later, the Throne Hall served as an imperial museum.

Other

palaces and structures :

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis

Huma bird capital at Persepolis

Bull capital at Persepolis

Ruins of the Hall of the Hundred Columns, Persepolis Tombs :

Tomb of Artaxerxes II, Persepolis It is commonly accepted that Cyrus the Great was buried in Pasargadae, which is mentioned by Ctesias as his own city. If it is true that the body of Cambyses II was brought home "to the Persians," his burying place must be somewhere beside that of his father. Ctesias assumes that it was the custom for a king to prepare his own tomb during his lifetime. Hence, the kings buried at Naghsh-e Rostam are probably Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II. Xerxes II, who reigned for a very short time, could scarcely have obtained so splendid a monument, and still less could the usurper Sogdianus. The two completed graves behind the compound at Persepolis would then belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The unfinished tomb, a kilometer away from the city, is debated to who it belongs. It is perhaps that of Artaxerxes IV, who reigned at the longest two years, or, if not his, then that of Darius III (Codomannus), who is one of those whose bodies are said to have been brought "to the Persians." Since Alexander the Great is said to have buried Darius III at Persepolis, then it is likely the unfinished tomb is his.

Another

small group of ruins in the same style is found at the village of

Haji Abad, on the Pulvar River, a good hour's walk above Persepolis.

These formed a single building, which was still intact 900 years

ago, and was used as the mosque of the then-existing city of Estakhr.

Babylonian version of an inscription of Xerxes I, the "XPc inscription" The relevant passages from ancient scholars on the subject are set out below :

(Diod.

17.70.1-73.2) 17.70 (1) Persepolis was the capital of the Persian

kingdom. Alexander described it to the Macedonians as the most hateful

of the cities of Asia, and gave it over to his soldiers to plunder,

all but the palaces. (2) It was the richest city under the sun,

and the private houses had been furnished with every sort of wealth

over the years. The Macedonians raced into it, slaughtering all

the men whom they met and plundering the residences; many of the

houses belonged to the common people and were abundantly supplied

with furniture and wearing apparel of every kind....

Modern

events :

The

controversy of the Sivand Dam :

Many archaeologists [who?] worry that the dam's placement between the ruins of Pasargadae and Persepolis will flood both. Engineers involved with the construction deny this claim, stating that it is impossible, because both sites sit well above the planned waterline. Of the two sites, Pasargadae is considered the more threatened.

Archaeologists are also concerned that an increase in humidity caused by the lake will speed Pasargadae's gradual destruction. However, experts from the Ministry of Energy believe this would be negated by controlling the water level of the dam reservoir.

Museums

(outside Iran) that display material from Persepolis :

Forgotten Empire Exhibition, the British Museum

Forgotten Empire Exhibition, the British Museum

Persepolitan rosette rock relief, kept at the Oriental Institute

General views :

A general view of the ruins at Persepolis

A general view of the ruins at Persepolis

A general view of the ruins at Persepolis

A general view of the ruins at Persepolis

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.webm.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(4688859421).jpg)

_(4688678112).jpg)

.jpg)

.1.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)