| ACHAEMENID CONQUEST OF THE INDUS VALLEY The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley refers to the Achaemenid military conquest and occupation of the territories of the North-western regions of the Indian subcontinent, from the 6th to 4th centuries BC. The conquest of the areas as far as the Indus river is often dated to the time of Cyrus the Great, in the period between 550-539 BCE. The first secure epigraphic evidence, given by the Behistun Inscription, gives a date before or about 518 BCE. Achaemenid penetration into the area of the Indian subcontinent occurred in stages, starting from northern parts of the River Indus and moving southward. These areas of the Indus valley became formal Achaemenid satrapies as mentioned in several Achaemenid inscriptions. The Achaemenid occupation of the Indus Valley ended with the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great circa 323 BCE. The Achaemenid occupation, although less successful than that of the later Greeks, Sakas or Kushans, had the effect of acquainting India to the outer world.

Background and invasion :

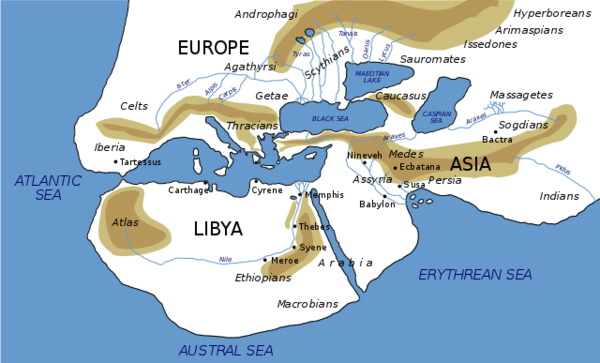

India appears to the east of the inhabited world according to Herodotus, 500 BCE

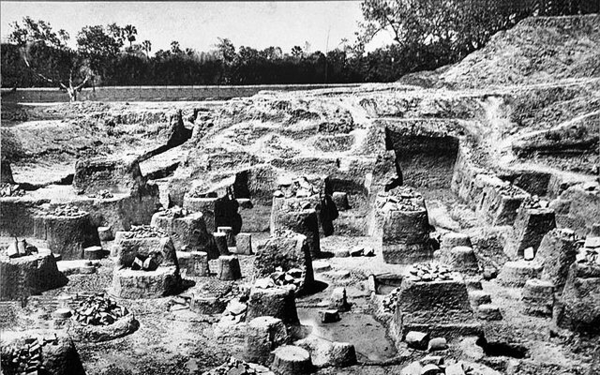

Ruins at Bhir Mound representing the city of Taxila during the Achaemenid period For millennia, the northwestern part of India had maintained some level of trade relations with the Near East. Finally, the Achaemenid Empire underwent a considerable expansion, both east and west, during the reign of Cyrus the Great (c.600–530 BC), leading the dynasty to take a direct interest into the region of northwestern India.

Cyrus

the Great :

Darius

I :

Darius I on his tomb The exact area of the Province of Hindush is uncertain. Some scholars have described it as the middle and lower Indus Valley and the approximate region of modern Sindh, but there is no known evidence of Achaemenid presence in this region, and deposits of gold, which Herodotus says was produced in vast quantities by this Province, are also unknown in the Indus delta region. Alternatively, Hindush may have been the region of Taxila and Western Punjab, where there are indications that a Persian satrapy may have existed. There are few remains of Achaemenid presence in the east, but, according to Fleming, the archaeological site of Bhir Mound in Taxila remains the "most plausible candidate for the capital of Achaemenid India", based on the fact that numerous pottery styles similar to those of the Achaemenids in the East have been found there, and that "there are no other sites in the region with Bhir Mound's potential".

According to Herodotus, Darius I sent the Greek explorer Scylax of Caryanda to sail down the Indus river, heading a team of spies, in order to explore the course of the Indus river. After a periplus of 30 months, Scylax is said to have returned to Egypt near the Red Sea, and the seas between the Near East and India were made use of by Darius.

Also according to Herodotus, the territories of Gandhara, Sattagydia, Dadicae and Aparytae formed the 7th province of the Achaemenid Empire for tax-payment purposes, while Indus (called "Indos" in Greek sources) formed the 20th tax region.

Achaemenid army :

Greek

Ionian (Yavanas), Scythian (Sakas) and Persian (Parasikas) soldiers

of the Achaemenid army, as described on Achaemenid royal tombs from

circa 500 to 338 BCE.

The Persians may have later participated, together with Sakas and Greeks, in the campaigns of Chandragupta Maurya to gain the throne of Magadh circa 320 BCE. The Mudrarakshasa states that after Alexander's death, an alliance of "Shak - Yavan - Kamboj - Parasik - Bahlik" was used by Chandragupta Maurya in his campaign to take the throne in Magadh and found the Mauryan Empire. The Sakas were the Scythians, the Yavanas were the Greeks, and the Parasikas were the Persians. David Brainard Spooner observed of Chandragupta Maurya that "it was with largely the Persian army that he won the throne of India."

Inscriptions

and accounts

Hindush ("India")

Sattagydia

Gandhar These events were recorded in the imperial inscriptions of the Achaemenids (the Behistun inscription and the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription, as well as the accounts of Herodotus (483–431 BCE), and of the Hellenistic accounts of the Greek conquests in India (circa 320 BCE). The Greek Scylax of Caryanda, who had been appointed by Darius I to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to Suez left an account, the Periplous, of which fragments from secondary sources have survived. Hecataeus of Miletus (circa 500 BCE) also wrote about the "Indus Satrapies" of the Achaemenids.

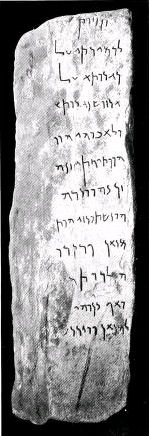

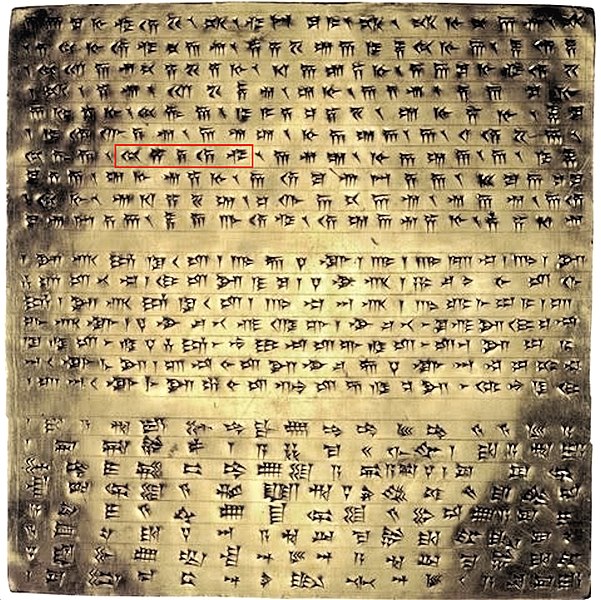

Behistun

inscription :

King

Darius says :

—

Behistun Inscription of Darius I.

Statue

of Darius inscriptions :

Apadana Palace foundation tablets :

Gold foundation plate of Darius I in the Apadana Palace in Persepolis with the word Hidauv, locative of "Hiduš" Four identical foundation tablets of gold and silver, found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the Apadana Palace, also contained an inscription by Darius I in Old Persian cuneiform, which describes the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms, from the Indus valley in the east to Lydia in the west, and from the Scythians beyond Sogdia in the north, to the African Kingdom of Kush in the south. This is known as the DPh inscription. The deposition of these foundation tablets and the Apadana coin hoard found under them, is dated to circa 515 BCE.

Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid. King Darius says: This is the kingdom which I hold, from the Sacae who are beyond Sogdia to Kush, and from Sind (Old Persian: "Hidauv", locative of "Hiduš", i.e. "Indus valley") to Lydia (Old Persian: "Spardâ") - [this is] what Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods, bestowed upon me. May Ahuramazda protect me and my royal house!

—

DPh inscription of Darius I in the foundations of the Apadana Palace

The

Naqsh-e Rustam DNa inscription, on the tomb of Darius I, mentioning

all three Indian territories: Sattagydia (Thataguš), Gandara

(Gandhar, Gadara) and India (Hiduš) as part of the Achaemenid

Empire.

Hiduš (in Old Persian cuneiform) also appears later as a Satrapy in the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription at the end of the reign of Darius, who died in 486 BCE. The DNa inscription on Darius' tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam near Persepolis records Gadara (Gandara) along with Hiduš and Thataguš (Sattagydia) in the list of satrapies.

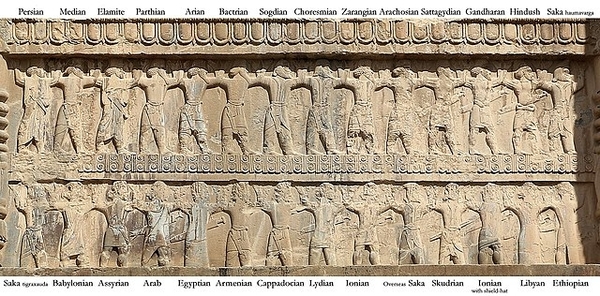

King Darius says : By the favor of Ahuramazda these are the countries which I seized outside of Persia; I ruled over them; they bore tribute to me; they did what was said to them by me; they held my law firmly; Media, Elam, Parthia, Aria, Bactria, Sogdia, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Arachosia, Sattagydia, Gandara (Gadara), India (Hiduš), the haoma-drinking Scythians, the Scythians with pointed caps, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, Cappadocia, Lydia, the Greeks (Yauna), the Scythians across the sea (Sakâ), Thrace, the petasos-wearing Greeks [Yaunâ], the Libyans, the Nubians, the men of Maka and the Carians.

—

Naqsh-e Rustam inscription of Darius I (circa 490 BCE)

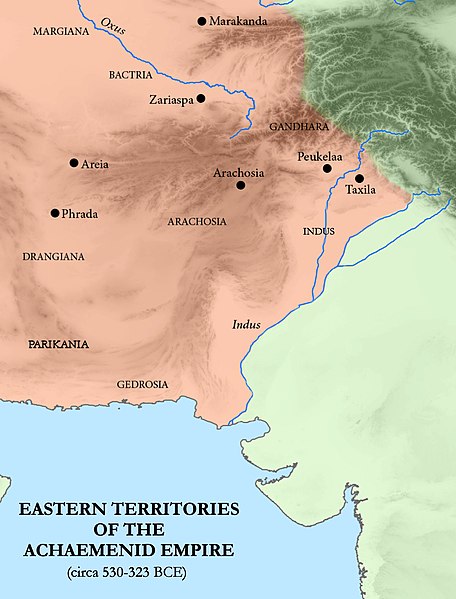

Eastern territories of the Achaemenid Empire

The names of the three Ancient Indian provinces still appear in trilingual cuneiform labels above their respective figures on the tomb of Artaxerxes II (c.358 BCE) The nature of the administration under the Achaemenids is uncertain. Even though the Indian provinces are called "satrapies" by convention, there is no evidence of there being any satraps in these provinces. When Alexander invaded the region, he did not encounter Achaemenid satraps in the Indian provinces, but local Indian rulers referred to as hyparchs ("Vice-Regents"), a term that connotes subordination to the Achaemenid rulers. The local rulers may have reported to the satraps of Bactria and Arachosia.

Achaemenid

lists of Provinces :

The Hinduš province, remained loyal till Alexander's invasion. Circa 400 BC, Ctesias of Cnidus related that the Persian king was receiving numerous gifts from the kings of "India" (Hinduš). Ctesias also reported Indian elephants and Indian mahouts making demonstrations of the elephant's strength at the Achaemenid court.

By about 380 BC, the Persian hold on the region was weakening, but the area continued to be a part of the Achaemenid Empire until Alexander's invasion.

Darius III (c. 380 – July 330 BC) still had Indian units in his army. In particular he had 15 war elephants at the Battle of Gaugamela for his fight against Alexander the Great.

Indian soldiers on the tomb of Darius I (c.500 BCE)

Indian soldiers on the tomb of Xerxes I (c.480 BCE)

Indian soldiers on the tomb of Artaxerxes I (c.430 BCE)

Indian soldiers on the tomb of Darius II (c.410 BCE)

Indian soldiers on the tomb of Artaxerxes II (c.370 BCE)

Indian soldiers on the tomb of Artaxerxes III (c.340 BCE) Indian

tributes

Hindush Tribute Bearers on the Apadana Staircase 8, circa 500 BCE

A small but heavy load: Indian tribute bearer at Apadana, probably carrying gold dust. 1 liter of gold weighs 19.3 kg The reliefs at the Apadana Palace in Persepolis describe tribute bearers from 23 satrapies visiting the Achaemenid court. These are located at the southern end of the Apadana Staircase. Among the foreigners the Arabs, the Thracians, the Bactrians, the Indians (from the Indus valley area), the Parthians, the Cappadocians, the Elamites or the Medians. The Indians from the Indus valley are bare-chested, except for their leader, and barefooted and wear the dhoti. They bring baskets with vases inside, carry axes, and drive along a donkey. One man in the Indian procession carries a small but visibly heavy load of four jars on a yoke, suggesting that he was carrying some of the gold dust paid by the Indians as tribute to the Achaemenid court.

According to the Naqsh-e Rustam inscription of Darius I (circa 490 BCE), there were three Achaemenid Satrapies in the subcontinent: Sattagydia, Gandara, Hiduš.

Tribute payments :

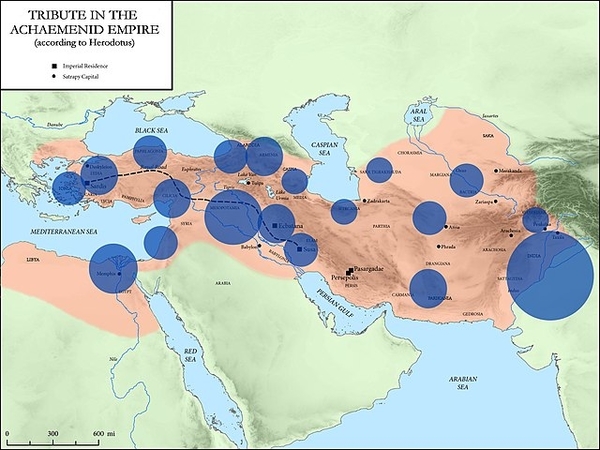

Volume of annual tribute per district, in the Achaemenid Empire, according to Herodotus The conquered area was the most fertile and populous region of the Achaemenid Empire. An amount of tribute was fixed according to the richness of each territory. India was already famous for its gold.

Herodotus (who makes several comments on India) published a list of tribute-paying nations, classifying them in 20 Provinces. The Province of Indos (the Indus valley) formed the 20th Province, and was the richest and most populous of the Achaemenid Provinces.

The Indians made up the twentieth province. These are more in number than any nation known to me, and they paid a greater tribute than any other province, namely three hundred and sixty talents of gold dust.

—

Herodotus, III 94.

Gandaran delegation at Apadana Palace The territories of Gandara, Sattagydia, Dadicae (north-west of the Kashmir Valley) and the Aparytae (Afridis) are named separately, and were aggregated together for taxation purposes, forming the 7th Achaemenid Province, and paying overall a much lower tribute of 170 talents together (about 5151 kg, or 5.1 tons of silver), hence only about 1.5% of the total revenues of the Achaemenid Empire :

The Sattagydae, Gandarii, Dadicae and Aparytae paid together a hundred and seventy talents; this was the seventh province

— Herodotus, III 91.

Ancient Indian soldiers of the three territories of Sattagydia, Gandhara and Hindush respectively, supporting the throne of Xerxes I on his tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam. See also complete relief. c. 480 BCE

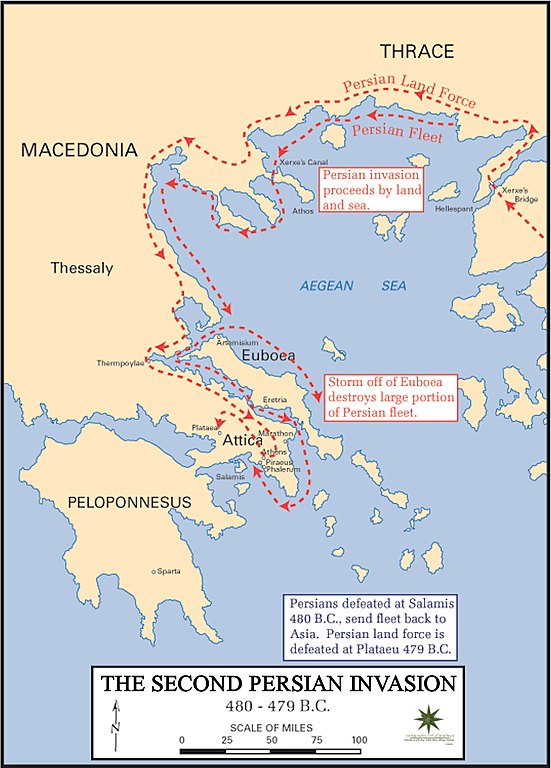

Indian soldiers of the Achaemenid army participated to the Second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BCE) The Indians also supplied Yaka wood (teak) for the construction of Achaemenid palaces, as well as war elephants such as those used at Gaugamela. The Susa inscriptions of Darius explain that Indian ivory and teak were sold on Persian markets, and used in the construction of his palace.

Contribution

to Achaemenid war efforts

Herodotus, in his description of the multi-ethnic Achaemenid army invading Greece, described the equipment of the Indians :

The Indians wore garments of tree-wool, and carried bows of reed and iron-tipped arrows of the same. Such was their equipment; they were appointed to march under the command of Pharnazathres son of Artabates.

— Herodotus VII 65

Probable Spartan hoplite (Vix crater, c. 500 BCE), and a Hindush warrior of the Achaemenid army (tomb of Xerxes I, c. 480 BCE), at the time of the Second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BCE) Herodotus also explains that the Indian cavalry under the Achaemenids had an equipment similar that of their foot soldiers :

The Indians were armed in like manner as their foot; they rode swift horses and drove chariots drawn by horses and wild asses.

—

Herodotus VII 86

The Bactrians in the army wore a headgear most like to the Median, carrying their native bows of reed, and short spears. The Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, Gandarians, and Dadicae in the army had the same equipment as the Bactrians. The Parthians and Chorasmians had for their commander Artabazus son of Pharnaces, the Sogdians Azanes son of Artaeus, the Gandarians and Dadicae Artyphius son of Artabanus.

—

Herodotus VII 64-66

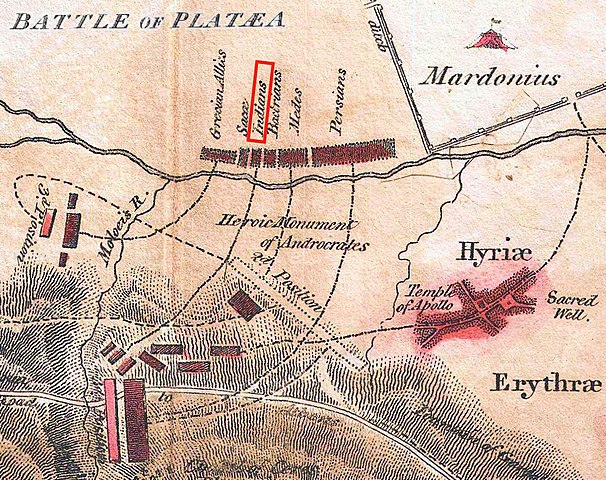

Indian corps at the Battle of Plataea, 479 BCE Mardonius there chose out first all the Persians called Immortals, save only Hydarnes their general, who said that he would not quit the king's person; and next, the Persian cuirassiers, and the thousand horse, and the Medes and Sacae and Bactrians and Indians, alike their footmen and the rest of the horsemen. He chose these nations entire; of the rest of his allies he picked out a few from each people, the goodliest men and those that he knew to have done some good service... Thereby the whole number, with the horsemen, grew to three hundred thousand men.

—

Herodotus VIII, 113.

Depictions

:

The three types of Indian soldiers still appear (upper right corner) among the soldiers of the Achaemenid Empire on the tomb of Artaxerxes III (who died in 338 BCE) The presence of the three ethnicities of Indian soldiers on the all the tombs of the Achaemenid rulers after Darius, except for the last ruler Darius III who was vanquished by Alexander at Gaugamela, suggest that the Indians were under Achaemenid dominion at least until 338 BCE, date of the end of the reign of Artaxerxes III, before the accession of Darius III, that is, less than 10 years before the campaigns of Alexander in the East and his victory at Gaugamela.

Indians

at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE) :

Fifteen Indian war elephants were also part of the army of Darius III at Gaugamela. They had specifically been brought from India. Still, it seems they did not participate to the final battle, probably because of fatigue. This was a relief for the armies of Alexander, who had no previous experience of combat against war elephants. The elephants were captured with the baggage train by the Greeks after the engagement.

Gandaran soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I tomb

Gandaran soldier (enhanced detail)

Sattagydian soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I tomb

Sattagydian soldier (enhanced detail)

Hindush soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I tomb

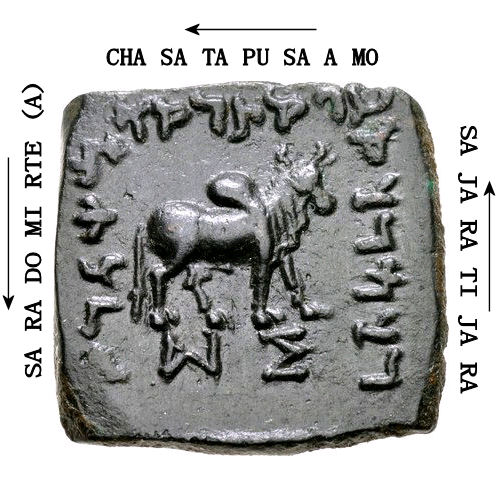

Hindush soldier (enhanced detail) Greek and Achaemenid coinage :

Achaemenid Empire coin minted in the Kabul Valley. Circa 500-380 BCE

"Bent bar" minted under Achaemenid administration, of the type found in large quantities in the Chaman Hazouri hoard and the Bhir Mound hoard in Taxila Coin finds in the Chaman Hazouri hoard in Kabul, or the Shaikhan Dehri hoard in Pushkalavati in Gandhara, near Charsadda, as well as in the Bhir Mound hoard in Taxila, have revealed numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE which circulated in the area, at least as far as the Indus during the reign of the Achaemenids, who were in control of the areas as far as Gandhar.

Kabul

and Bhir Mound hoards :

This numismatic discovery has been very important in studying and dating the history of coinage of India, since it is one of the very rare instances when punch-marked coins can actually be dated, due to their association with known and dated Greek and Achaemenid coins in the hoard. The hoard supports the view that punch-marked coins existed in 360 BCE, as suggested by literary evidence.

Daniel Schlumberger also considers that punch-marked bars, similar to the many punch-marked bars found in north-western India, initially originated in the Achaemenid Empire, rather than in the Indian heartland :

“The punch-marked bars were up to now considered to be Indian (...) However the weight standard is considered by some expert to be Persian, and now that we see them also being uncovered in the soil of Afghanistan, we must take into account the possibility that their country of origin should not be sought beyond the Indus, but rather in the oriental provinces of the Achaemenid Empire" —

Daniel Schlumberger, quoted from Trésors Monétaires,

p.42.

Pushkalavati

hoard :

According to Joe Cribb, these early Greek coins were at the origin of Indian punch-marked coins, the earliest coins developed in India, which used minting technology derived from Greek coinage.

Influence

of Achaemenid culture in the Indian subcontinent

Followers

of the Buddh :

Panini

:

Kautilya

and Chandragupta Maurya :

Astronomical and astrological knowledge was also probably transmitted to India from Babylon during the 5th century BCE as a consequence of the Achaemenid presence in the sub-continent.

Palatial art and architecture: Pataliputra :

The Masarh lion. The sculptural style is "unquestionably Achaemenid" Various Indian artefacts tend to suggest some Perso-Hellenistic artistic influence in India, mainly felt during the time of the Mauryan Empire. The sculpture of the Masarh lion, found near the Maurya capital of Pataliputra, raises the question of the Achaemenid and Greek influence on the art of the Maurya Empire, and on the western origins of stone carving in India. The lion is carved in Chunar sandstone, like the Pillars of Ashok, and its finish is polished, a feature of the Maurya sculpture. According to S.P. Gupta, the sculptural style is unquestionably Achaemenid. This is particularly the case for the well-ordered tubular representation of whiskers (vibrissas) and the geometrical representation of inflated veins flush with the entire face. The mane, on the other hand, with tufts of hair represented in wavelets, is rather naturalistic. Very similar examples are however known in Greece and Persepolis. It is possible that this sculpture was made by an Achaemenid or Greek sculptor in India and either remained without effect, or was the Indian imitation of a Greek or Achaemenid model, somewhere between the fifth century B.C. and the first century B.C., although it is generally dated from the time of the Maurya Empire, around the 3rd century B.C.

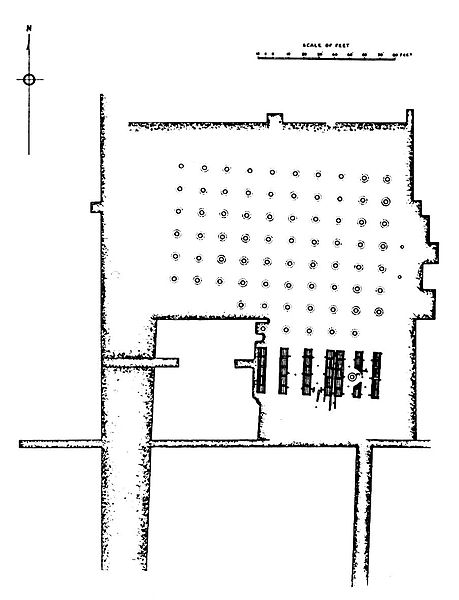

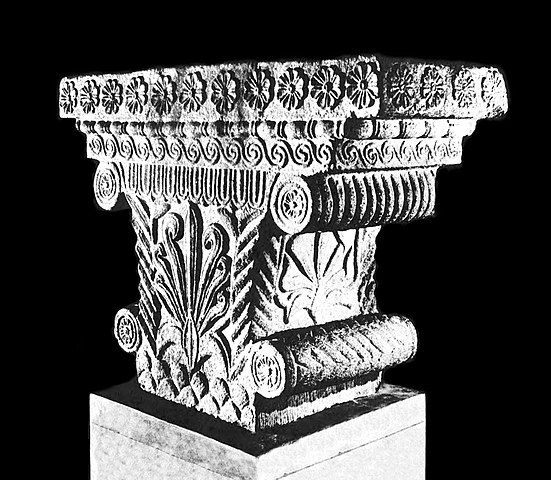

The Pataliputra palace with its pillared hall shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftsmen. Mauryan rulers may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments. This may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great. The Pataliputra capital, or also the Hellenistic friezes of the Rampurva capitals, Sankissa, and the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya are other examples.

The renowned Mauryan polish, especially used in the Pillars of Ashok, may also have been a technique imported from the Achaemenid Empire.

Plan of the 80-column pillared hall in Pataliputra

The Pataliputra capital, generally described as "Perso-Hellenistic"

Griffin of Pataliputra

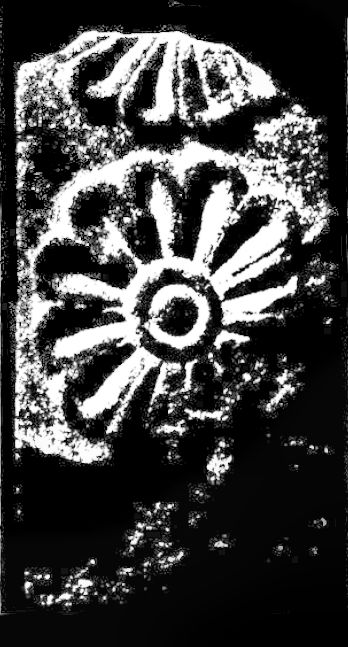

Lotus motifs in Pataliputra Rock-cut architecture :

Lycian Tomb of Payava (dated 375-360 BCE) and Lomas Rishi cave entrance (dated circa 250 BCE)

Ajanta Cave 9 (dated 1st century BCE) The similarity of the 4th century BCE Lycian barrel-vaulted tombs, such as the tomb of Payava, in the western part of the Achaemenid Empire, with the Indian architectural design of the Chaitya (starting at least a century later from circa 250 BCE, with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves group), suggests that the designs of the Lycian rock-cut tombs travelled to India along the trade routes across the Achaemenid Empire.

Early on, James Fergusson, in his " Illustrated Handbook of Architecture", while describing the very progressive evolution from wooden architecture to stone architecture in various ancient civilizations, has commented that "In India, the form and construction of the older Buddhist temples resemble so singularly these examples in Lycia". The structural similarities, down to many architectural details, with the Chaitya-type Indian Buddhist temple designs, such as the "same pointed form of roof, with a ridge", are further developed in The cave temples of India. The Lycian tombs, dated to the 4th century BCE, are either free-standing or rock-cut barrel-vaulted sarcophagi, placed on a high base, with architectural features carved in stone to imitate wooden structures. There are numerous rock-cut equivalents to the free-standing structures and decorated with reliefs. Fergusson went on to suggest an "Indian connection", and some form of cultural transfer across the Achaemenid Empire. The ancient transfer of Lycian designs for rock-cut monuments to India is considered as "quite probable".

Art historian David Napier has also proposed a reverse relationship, claiming that the Payava tomb was a descendant of an ancient South Asian style, and that Payava may actually have been a Graeco-Indian named "Pallav".

Monumental columns: the Pillars of Ashok :

Highly polished Achaemenid load-bearing column with lotus capital and animals, Persepolis, c. 5th-4th BCE

Lion Capital of Ashok from Sarnath Regarding the Pillars of Ashok, there has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia, since the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis have similarities, and the "rather cold, hieratic style" of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashok especially shows "obvious Achaemenid and Sargonid influence".

Hellenistic influence has also been suggested. In particular the abaci of some of the pillars (especially the Rampurva bull, the Sankissa elephant and the Allahabad pillar capital) use bands of motifs, like the bead and reel pattern, the ovolo, the flame palmettes, lotuses, which likely originated from Greek and Near-Eastern arts. Such examples can also be seen in the remains of the Mauryan capital city of Pataliputra.

Frieze of the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya Aramaic language and script :

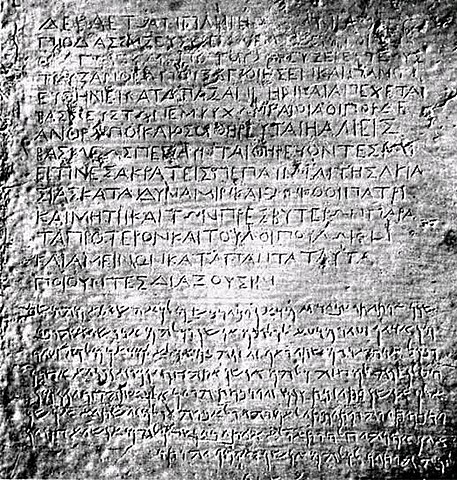

The Aramaic Inscription of Taxila The Aramaic language, official language of the Achaemenid Empire, started to be used in the Indian territories. Some of the Edicts of Ashok in the north-western areas of Ashok's territory, in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, used Aramaic (the official language of the former Achaemenid Empire), together with Prakrit and Greek (the language of the neighbouring Greco-Bactrian kingdom and the Greek communities in Ashok's realm).

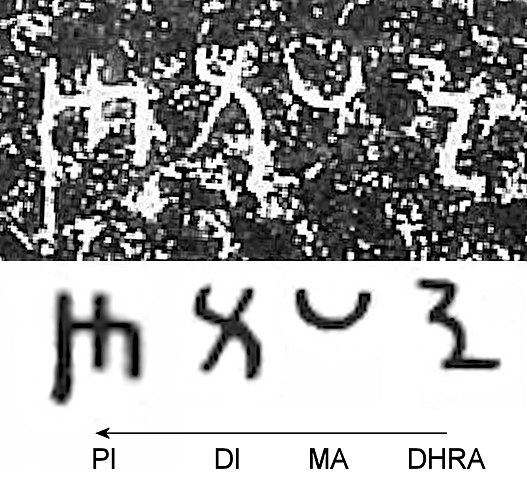

The Indian Kharosthi script shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indic languages. One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid Empire's conquest of the Indus River (modern Pakistan) in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years, reaching its final form by the 3rd century BCE where it appears in some of the Edicts of Ashok.

Edicts

of Ashok :

Several of the Edicts of Ashok, such as the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription or the Taxila inscription were written in Aramaic, one of the official languages of the former Achaemenid Empire.

The word Dipi ("Edict") in the Edicts of Ashok, identical with the Achaemenid word for "writing"

The Kharoshthi script is generally considered as a development from Aramaic

The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription of Ashok (circa 256 BCE) in Greek and Aramaic Figurines of foreigners in Mathura :

"Ethnic head", Mathura, c. 2nd century BCE. Mathura Museum

"Persian Nobleman clad in coat dupatta trouser and turban", Mathura, c. 2nd Century BCE. Mathura Museum Figurines of Persian foreigners in Mathura (4th-2nd century CE) :

Some relatively high quality terracotta statuettes have been recovered from the Mauryan Empire strata in the excavations of Mathura in northern India. Most of these terracottas show what appears to be female deities or mother goddesses. However, several figures of foreigners also appear in the terracottas from the 4th to the 2nd century BCE, which are either described simply as "foreigners" or Persian or Iranian because of their foreign features. These figurines might reflect the increased contacts of Indians with Iranian people during this period. Several of these seem to represent foreign soldiers who visited India during the Mauryan period and influenced modellers in Mathura with their peculiar ethnic features and uniforms. One of the terracotta statuettes, a man nicknamed the "Persian nobleman" and dated to the 2nd century BCE, can be seen wearing a coat, scarf, trousers and a turban.

Religion

:

"Hystaspes, a very wise monarch, the father of Darius. Who while boldly penetrating into the remoter districts of upper India, came to a certain woody retreat, of which with its tranquil silence the Brahmans, men of sublime genius, were the possessors. From their teaching he learnt the principles of the motion of the world and of the stars, and the pure rites of sacrifice, as far as he could; and of what he learnt he infused some portion into the minds of the Magi, which they have handed down by tradition to later ages, each instructing his own children, and adding to it their own system of divination".

—

Ammianus Marcellinus, XXIII. 6.

Historically, the life of the Buddh also coincided with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley. The Achaemenid occupation of the areas of Gandara and Hinduš, which was to last for about two centuries, was accompanied by Achaemenid religions, reformed Mazdaism or early Zoroastrianism, to which Buddhism might also have in part reacted. In particular, the ideas of the Buddh may have partly consisted in a rejection of the "absolutist" or "perfectionist" ideas contained in these Achaemenid religions.

Still, according to Christopher I. Beckwith, commenting on the content of the Edicts of Ashok, the early Buddhist concepts of karma, rebirth, and affirming that good deeds with be rewarded in this life and the next, in Heaven, probably find their origin in Achaemenid Mazdaism, which had been introduced in India from the time of the Achaemenid conquest of Gandara.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ |

.jpg)

_Upper_Relief_soldiers_with_labels.jpg)

_circa_480_BCE_in_the_Naqsh-e_Roastam_reliefs_of_Xerxes_I.jpg)

_Upper_Relief_Indian_soldiers_with_labels.jpg)