| MOURU - 2 Kelleli

:

Toguluk / Togulok :

Artist's reconstruction of Toguluk / Togulok

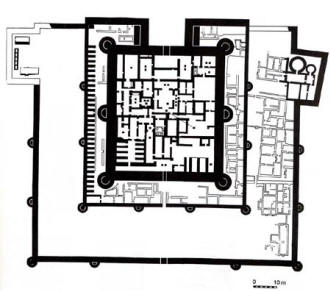

Plan of Togolok 21. Photo credit: various. Kispesti Kozert

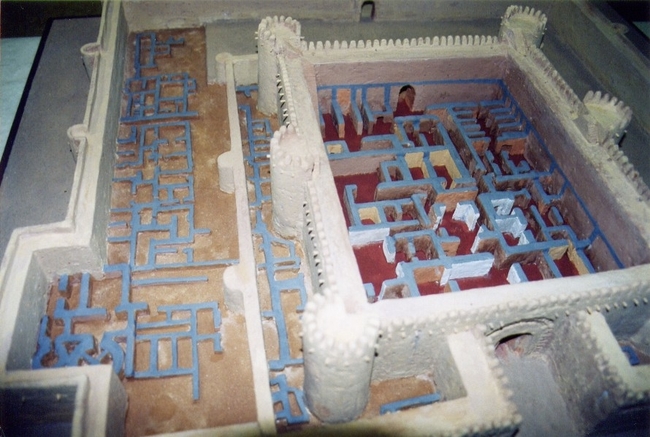

Reconstructed model of Togolok 21 Photo credit:Aula Didactica Togolok consists of two sites, Togolok 1 and Togoluk 21. Togoluk 21 is the larger of the two sites. According to Viktor Sarianidi :

"The next and last shrine excavated is located in the settlement of Togolok 21, which dates to the late 2nd millennium. Taking into account its large overall size (larger than the fortress of South Gonur), it is possible that the shrine of Togolok 21 served the inhabitants of the whole country of Margiana in the late Bronze Age. Similar to the above-described shrines, there is a domestic area near Togolok 21 associated with the shrine. At Gonur depe and Togolok 1 the settlements are many times larger than the shrines, while in Togolok 21 the settlement is a great deal smaller than the shrine itself.

"The shrine of Togolok 21 was built at the top of a small natural hill. Along the outer face of the exterior wall are circular and semicircular hollow towers. In the northern part of the wall are two pylons between which a central gateway, supposed to be the entrance to the shrine, is located. The second entrance was built in the middle of the southern wall. The whole inner area was not built up except at the western side where some extremely narrow rooms are located which appear to have had arched ceilings. Their purpose is unclear. Two altar sites located opposite each other in the northern part of the shrine were perhaps used for carrying out ritual ceremonies associated with libations and fire rituals."

Adji Kui :

Taip :

Very Poor Archaeological Practices :

Thousands of pottery shards are scattered across the Gonur-depe excavation site

Visitors steps over these priceless artefacts further destroying

a priceless treasure. Photo credit: Eurasianet.org

"Without a greater commitment from the Turkmen state, funding will dry up, the guide said, and Gonur-depe will slowly blow away."

Also

see :

Viktor Sarianidi :

For over 30 years, Professor Viktor Sarianidi, Laureate of the Magtymguly International Prize and Doctor of History, has headed the Margiana Archaeological Expedition that has conducted excavations in Turkmenistan and other Central Asian states.

The sites include Namazga-Depe, Altyn-Depe, Delbarjin, the Dashly Oasis, Toholok 21, Gonur, Kelleli, Sapelli, and Djarkutan. In Gonur-Depe for instance, where others saw only sand and scrub, Sarianidi saw the remnants of a wealthy town protected by high walls and battlements. (Indeed all the sites have high protective walls.)

Ancient pottery carelessly strewn all over Sarianidi supervised sites While some researchers have applauded Sarianidi for his dedication, others view him as an eccentric, employing brutish and old-fashioned techniques. These days Western archaeologists typically unearth sites with dental instruments and mesh screens, meticulously sifting soil for traces of pollen, seeds, and ceramics. Sarianidi uses bulldozers to expose old foundations, largely ignores botanical finds, and publishes few details on layers, ceramics, and other mainstays of modern archaeology. Ceramics that he has unearthed and which for millennia have remained protected deep in the sand now lie strewn about his sites with visitors stepping over them as they walk around. Local residents and animals also climb all over the fragile earthen structures. His reports are also sensationalistic, conjectural and poorly researched. Sarianidi's conclusions are routinely contradicted by a more sober analysis. Nevertheless, his findings have provided rich fodder for those captivated by the fantasy generated by his claims. It is unfortunate that his lack of credibility by serious scholars may obscure his other accomplishments. A further tragedy that may overshadow his work is that paradoxically he may have done a disservice in unearthing the ruins. The exposed ruins have been left with no protection and are being rapidly eroded.

As a Greek growing up in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, under Stalinist rule, Sarianidi was denied training in law and turned to history instead. Ultimately, it proved too full of groupthink for his taste, so he opted for archaeology. "It was more free because it was more ancient," he says. During the 1950s he drifted, spending seasons between digs unemployed. He refused to join the Communist Party, despite the ways it might have helped his career. Eventually, in 1959, his skill and tenacity earned him a coveted position at the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow, but it was years before he was allowed to direct a dig. In 1996, Sarianidi moved to Greece where he currently lives.

BMAC & Andronovo Archaeological Complexes :

Bronze Age Indo-Iranian Archaeological Complexes. Image credit: Wikipedia In 1976, Viktor Sarianidi proposed that the Bronze Age archaeological sites dating from c. 2200 to 1700 BCE and located in present day Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, were the remains of a connected Bronze Age civilization centered on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus). He named the complex the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) and the inhabitants of that period and region, the Oxus civilization.

The name Andronovo complex comes from the village of Andronovo in Siberia where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. The name has been used to refer to a set of contemporaneous Bronze Age cultures that flourished c. 2300–1000 BCE in western Siberia and the west Asiatic steppes of Kazakhstan. This culture is thought to have been a pastoral people who reared horses, cattle, sheep and goats.

The names of these groupings are those given by archaeologists and have no relation to historical names or one to another. They are better termed as archaeological complexes or archaeological horizons.

There are problems and inconsistencies using these archaeological complexes or archaeological horizons to construct history and anthropological (incorrectly called racial) or cultural connections. The archaeological horizons are the time period in which the groups are believed to have existed are based mainly on pottery and artefact similarities and datings. If no corresponding pottery or artefacts are found after a particular dating, the group is assumed to have disappeared or to have been displaced due to war, famine or disease.

Sarianidi is quoted (as cited in Bryant 2001:207) as saying that "direct archaeological data from Bactria and Margiana show without any shade of doubt that Andronovo tribes penetrated to a minimum extent into Bactria and Margianian oases". These assertions are artificial constructs built on speculation rather than objective data.

The following are quotes from the University of Chicago's page on Archaeology and Language, The Indo-Iranians by C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky :

"This review of recent archaeological work in Central Asia and Eurasia attempts to trace and date the movements of the Indo-Iranians—speakers of languages of the eastern branch of Proto-Indo-European that later split into the Iranian and Vedic families. Russian and Central Asian scholars working on the contemporary but very different Andronovo and Bactrian Margiana archaeological complexes of the 2d millennium BCE have identified both as Indo-Iranian, and particular sites so identified are being used for nationalist purposes. There is, however, no compelling archaeological evidence that they had a common ancestor or that either is Indo-Iranian. Ethnicity and language are not easily linked with an archaeological signature, and the identity of the Indo-Iranians remains elusive."

["C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky is Stephen Philips Professor of Archaeology in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University and Curator of Near Eastern Archaeology at Harvard's Peabody Museum (Cambridge, Mass. 02138, U.S.A.). Born in 1937, he was educated at Dartmouth College (B.A., 1959) and the University of Pennsylvania (M.A., 1964; Ph.D., 1965). His research interests concern the nature of the interaction between the Bronze Age civilizations of the Near East and their contemporary neighbors of the Iranian Plateau, the Indus Valley, the Arabian Peninsula, and Central Asia. His recent publications include Beyond the Tigris and Euphrates Bronze Age Civilizations (Tel Aviv: Ben Gurion University of the Negev Press, 1996) and (with Daniel Potts et al.) Excavations at Tepe Yahya, Iran: Third Millennium (American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 42)."]

It is regrettable that through conjecture alone, the Andronovo complex has been connected racially and culturally to the people of the BMAC complex. This error is compounded with the conjecture that the Andronovo complex is connected to the Aryans, misleading some to further believe that the Aryans originated in the Siberian steppes. Because some parts of the Andronovo complex are part of Russian Siberia, in an additional leap of faith, some people have translated the Andronovo region to mean the Russian steppes, leading some to state that the Aryans originated in the Russian steppes, a name that is usually associated with the western Russian steppes - west of the Caspian sea. One error leads to another. There is no credibility to the assertion that the Aryans originated in the Russian steppes.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |