| NISAIM Nisaya,

Nisa - Fifth Vendidad Nation :

The ancient nation of Nisa would have extended along the Kopet Dag mountains in both directions later becoming Parthava (Parthia). Its eastern neighbour would have been Mouru. The foothills of the Kopet Dag are scattered with the ruins of an ancient civilization, a fact that did not go unnoticed by Raphael Pumpelly, geologist from New York, in the early 1900s.

Ruins located near modern-day Bagir village, 18 km southwest of Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, and alongside the foothills of the Kopet Dag mountains, have been identified as Nisa and was said to have been founded by Arshak (Arsaces) I (reigned c. 247-211 BCE), the founder of the Parthian empire, and reputedly became the royal necropolis of the Parthian kings. Nisa was later renamed Mithradatkirt (fortress of Mithradat(a)/Mithridates) by Mithradat(a) I of Parthava (reigned c. 171-138 BCE).

The ruins include impressive buildings and fortifications, mausoleums and shrines, inscribed documents, and a treasury robbed of its contents. The artefacts found include art and ivory drinking cups with their outer rims decorated with ancient Iranian classical mythological scenes and themes. The ruins were declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2007.

Some have identified the ruins at Nisa with Parthaunisa, the first capital city of the Parthians, prior to its destruction by an earthquake.

Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923) Champion of a Central Asian Cradle of Civilization :

Raphael Pumpelly More than a century ago an unlikely geologist from New York put forth a proposition that "the fundamentals of civilization - organized village life, agriculture, the domestication of animals, weaving," (including mining and metal work) "originated in the oases of Central Asia long before the time of Babylon."

Raphael Pumpelly arrived at this conclusion after visiting Central Asia as a geologist and observing the ruins of cities on the ancient shorelines of huge, dried inland seas. By studying the geology of the area, he became one of the first individuals to investigate how environmental conditions could influence human settlement and culture. Pumpelly speculated that a large inland sea in central Asia might have once supported a sizeable population. He knew from his travels and study that the climate in Central Asia had become drier and drier since the time of the last ice age. As the sea began to shrink, it could have forced these people to move west, bringing civilization to westward and to the rest of the world. He hypothesized that the ruins of cities he saw were evidence of a great ancient civilization that existed when Central Asia was more wet and fertile than it is now.

Such assertions that civilization as we know it originated in Central Asia sounded radical at a time when the names of Egypt and Babylon, regions connected to the Bible, were considered to be the cradle of civilization. But Raphael Pumpelly was persistent. Forty years after his first trip to Central Asia, he convinced the newly established Andrew Carnegie Foundation to fund an expedition. Since the Russians controlled Central Asia, he charmed the authorities in Saint Petersburg into granting him permission for an archaeological excavation. The latter even provided Pumpelly with a private railcar. At the age of 65, Pumpelly was given the opportunity to prove his theory and he wasted no time in starting his work.

Anau :

On a previous trip, while travelling on Trans-Caspian railway along the foothills of rugged Kopet-Dag mountains which rise up to form the vast Iranian plateau, the three mounds or kurgans at Anau had caught Raphael Pumpelly's eye.

Anau is a site eight kilometres southeast of Turkmenistan's Ashgabat modern-day capital, Ashgabat, and its name is derived from Abi-Nau, meaning new water. In earlier times, its name was Gathar.

In the delta around Anau, there are three mounds or kurgans (also called tepe or depe), each containing ruins from a different period. The north mound has layers from the 5th millennium BCE to the 3rd millennium BCE, at which time in history the river Keltechinar appears to have changed course causing a population shift to the south mound that has layers from the mid-3rd millennium BCE to the 1st millennium BCE (the Bronze Age). The east mound has the most recent (medieval to classical period) ruins.

In 1886, a Russian general A. V. Komarov who mistakenly thought the mound was an ancient burial site with treasure worth plundering, had his army brigade cut through the north mound, bisecting the mound. When Pumpelly visited the site in 1903, his training as a geologist enabled him to see twenty stratified occupational layers in this trench. Pumpelly returned to the site in 1904 to start excavations along the Russian trench using sophisticated methods - methods in stark contrast with the plundering dig of the Russians.

Anau tepe in the distance Pumpelly carefully excavated the north mound by digging a series of eight terraces and shafts. He carefully labelled the position of each item he uncovered. He employed fine-scale archaeology methods (methods that are now utilized by modern archaeologists) by using sieves to capture seeds and tiny bones. Then he had specialists, such as botanists and anatomists, analyze his finds. These pioneering methods would only gradually be used by archaeologists over the next century. In the absence of modern methods like radiocarbon dating, Pumpelly used his training as a geologist, keeping careful stratigraphic records to date sites. His findings would come close to matching data collected years later using modern technology and at considerably greater cost.

Pumpelly's early interest in how humans respond to environmental change is still a keynote feature of archaeology. The kurgan digs unearthed pottery, objects of stone and metal, hearths and cooking utensils - even the remains of skeletons of children found near hearths. He discovered evidence of domesticated animals and cultivated wheat - evidence of the civilization the sought.

Later Pumpelly was to write in his memoirs, "A close watch was kept to save every object, large and small,... and to note its relation to its surroundings. I insisted that every shovelful contained a story if it could be interpreted." Indeed, every shovelful, even grain, and every shard had a story to tell.

The story of Anau that emerged was one of a planned walled city that was home to a community that farmed wheat, manufactured artefacts and traded with its neighbours.

His work had barely begun, when in 1904 a plague of locusts "filled the trenches faster than they could be shovelled," and plunged the area into famine, forcing him to abandon the dig, never to return. This phenomenon should not go unnoticed since it might provide clues on the reasons why some settlements appear to have been abandoned in ancient times.

Traveling eastward, he noted the mounds dotting the foothills of the Kopet-Dag, indicating that Anau was not an isolated town, but part of a community of settlements that stretched for a few hundred kilometres, settlements that based themselves on the waters and fertile soil brought down from the mountains. Leaving the mountains, Pumpelly followed the river Murgab north towards the Kara Kum desert. Extreme heat stopped him from exploring the upper reaches of the Murgab delta. Had he done so, he could surely have arrived on the unmistakeable depe mounds of Gonur. That discovery would have to wait for another seventy years and the efforts of a Russian archaeologist of Greek descent, Viktor Sarianidi.

Fredrik Hiebert

Fredrik Hiebert, an archaeologist with the National Geographic Society and formerly a professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, who conducted a 1988 dig in the Kara Kum Desert, says that one of the reasons why Pumpelly has been ignored by other archaeologists was their need to defend established theories and resulting bias. In 1904, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean were the accepted great centres of civilization. "So why in the world would Pumpelly have gone to Turkmenistan to look for civilization? To his peers, it made no sense; people couldn't comprehend it."

American team works at Anau with the the Kopet-Dag mountains in the background. Photo credit: Kenneth Garrett at Discover Magazine

Resumption of Anau Excavations :

According to Dr. Hiebert, while Anau is a small site compared to nearby Silk Road sites like Namazga depe and Altyn depe, it none-the-less shows evidence of involvement in a wide-reaching, managed system of distribution and trade occurring at perhaps hundreds of sites throughout the Central Asian Bronze Age period. "This pattern of small and large settlements having elite and bureaucratic functions is unique to the area," notes Dr. Hiebert.

In his report, Dr. Hiebert stated, "We like Anau because it was occupied for almost every period. Deposits stretch from the earliest village way of life (4500 BCE) to a Bronze Age town (2300 BCE) to a walled classical city (2nd c. BCE) which was eventually topped by a medieval mosque (1500th c CE) with glistening blue-green glazed tiles."

During his excavations, Dr. Hiebert uncovered a unique engraved stamp seal made from a shiny jet-black stone. The seal bore an inscription that was emphasized with a reddish brown pigment. The design of the inscription does not match any known writing or symbol system. Researchers are careful not to claim this is a form of writing, for if it were, it would represent one of the earliest writing systems known. Writes Dr. Hiebert: "Seals are used in the administrative system of an economy that needs to keep track of goods such as supplies for temples, barracks, or palaces."

Hiebert excavation unit where seal was discovered Dr. Hiebert's team discovered the stamp seal while excavating at the base of the Bronze Age mound at Anau. There they uncovered the eroded top of a very large, surprisingly well-built building with walls, that even 4300 years later, stand nearly two meters tall. Inside the rooms, archaeologists found the remains of finely made ceramics, some clearly from other regions, as well as and numerous pieces of clay used to seal vessels or parcels.

In 2004, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary conference of Pumpelly's 1904 Anau dig, Raphael's great-granddaughter Lisa Pompelli (who uses the original spelling of her family's Italian surname), accompanied Hiebert and his archaeological team to Turkmenistan to attend the conference and celebrate the opening of that country's museum devoted entirely to wheat and its early cultivation.

Ancient Kopet Dag Foothill Townships :

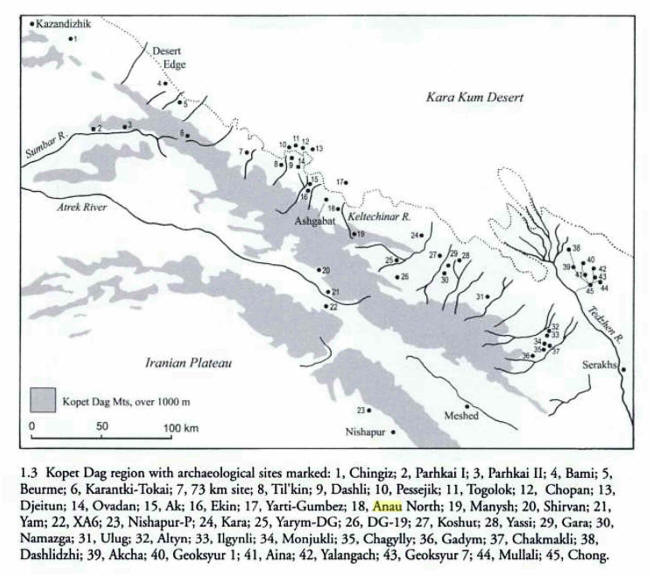

Archaeological sites along the northern foothills of the Kopet Dag Mountains. Image credit: A Central Asian village at the dawn of civilization, excavations at Anau,Turkmenistan by Fredrik Talmage Hiebert, Kakamurad Kurbansakhatov, Hubert Schmidt Following the ground breaking excavations and observations of Raphael Pumpelly, discoveries of the settlement of early prehistoric civilizations along the northern foothills of the Kopet Dag mountains are rewriting the history books. This vast archipelago of settlements stretches across 6,000 square kilometres. Modern dating methods date a settlement at Djeitun (not very far from Anau - see site #13 in the map above, #18 being Anau North) at c. 6500 BCE (Ceramic Neolithic period). Two other nearby sites #11. Togolok and #12 Chopan also date back to the early Djeitun period.

A number of the sites, for instance Altyn depe (#32 above and meaning golden hill), contain artefacts from Harappa in the Indus valley and Sumer / Mesopotamia in the Tigris-Euphrates valley indicating extensive and far-reaching trading along the Silk Roads during the Eneolithic Age (between the late 4th and the late 3rd millennia BCE). (cf. Altyn-Depe by Vadim Mikhailovich Masson and Henry N. Michael, Published by Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology.)

If because of climate change, the fertile areas had been receding south towards the mountains, it is reasonable to expect that earlier settlements might have existed in areas that are now part of the dessert. The earliest settlements discovered to this point show well established farming and building techniques. These would not have suddenly manifested themselves but would have taken generations to develop.

In many ways the work of discovering the secrets of the past has only just started. Impeded that war and a changing political environment, the world is only just waking up to the possibility that the Aryan heartland of Central Asia may have an equal claim to being the cradle of civilization.

References

:

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |