| URVA / KHAIRIZEM - 1 Zoroastrian

Era Historical Sites :

The grandeur of the original edifices in Khvarizem - fortresses, cities and temples - would have rivalled the Persian sites in the Iranian plateau - sites that are more commonly identified with the Zoroastrian era. In many respects, Khvarizem makes the better claim to being closer to the Zoroastrian heartland.

Map of Khairizem / Khvarizem/ Chorasmia Historical Sites. Base map courtesy Microsoft Encarta Shilpiq / Chilpik Dakhma :

A major Zoroastrian region is often identified by the presence of a tower of silence, a dakhma, and there are the ruins of a dakhma at Shilpiq (also spelt Chilpik) in Karakalpakstan.

Karakalpakstan Coat of Arms with dakhma to the bottom left of the sun Image: Homestead The people of Karakalpakstan use the dakhma ruins are a principle symbol of their province, placing it on their coat of arms, and in graphics, such as the New Year's sign in the capital city of Nokis as the defining feature of their province.

In addition, Karakalpak residents also celebrate Nowruz, the Zoroastrian / Aryan New Year's Day. Zoroastrianism, it would appear has a deep, pervasive connection with the land.

Archaeologists tell us that the Shilpiq / Chilpik dakhma was constructed sometime between the first century BCE and the first century CE. According to local legend, the region around the dakhma is also the place where Zarathushtra began to compose the Avesta.

The Shilpiq dakhma was used up to the time of the Arab invasion of Khvarizem in the early 7th century CE. There are signs of rebuilding or repair work in the 7th to 8th centuries CE and again in the 9th to 10th centuries CE.

Shilpiq / Chilpik dakhma. Photo: Miles Hunter at Flickr The circular structure of the dakhma is roughly 65 to 79 meters in diameter and sits on a fairly symmetrical conical 35-40 meters high hill. Its 15 metre high walls were built from pakhsa or compacted clay. They were probably taller when built and taper towards the top from a wide base. On the west side of the walls is an opening accessed by a 20 metre-long staircase. (In India, the door to the dakhma is placed on the east side of the structure.) At the start of the staircase is a tall pillar that can be seen from a distance. A ramp that starts from the river bank leads up to the pillar.

The Shilpiq dakhma would have served the surrounding region. Zoroastrian custom requires the body to the placed in the Dakhma shortly after death is confirmed and the fastest means of transporting a body to the Dakhma would have been by boat. The numerous river arms and canals would have made water transport the most practical means of transportation. In addition, the river at the time of the dakhma's use would have been wider and closer to the base of the hill making the walk to the top much shorter than it is today.

Funerary practices in Khvarizem, Sogdiana and the Semirechye indicate that after the bones of the body had been bleached and dried for about a year, the skeletal remains were then placed in ceramic ossuary containers and buried. It would be natural to expect that families would want to bury the remains closer to their towns rather than in the dakhma area and as such only a few ossuaries have been found at Shilpiq. The concentration of settlements are west at Mizdahkan (see below) and south of the Sultanuiz hills (Sultan Uvays Dag) and that is where a larger number of ossuaries have been found.

Currently, a north-south highway runs beside Shilpiq, with the provincial capital of Nukus 43 kilometres to the North. Nearby at Qara Tyube, bronze age petroglyphs can be found.

In 1940, Shilpiq was surveyed by Soviet archaeologist Sergei Tolstov and members of his early Khorezm Archaeological Expedition. There is evidence that the dakhma contained a tall pinnacle-like structure which was destroyed during Soviet rule in order to install a geodetic survey trig point. Regrettably, a telecommunications tower has also been built on the dakhma.

Mizdakan & Gyaur Kala :

Mizdahkan looking west with the Necropolis in the foreground and Gyaur Kala (Infidel Fortress) in the background Mizdakan was the second largest city of Khvarizem covering over 200 hectares and stretching two kilometres in one direction and one kilometre in the other. It lay west from Shilpiq, midway between Shilpiq and Kunya Urgench (or Kunha Gurganj), the capital of Khvarizem. (Kunya Urgench, a UN world heritage site, is today located across the border in Turkmenistan.)

Mizdakan was renowned throughout Asia as a city of art and culture, as well as one that as supported trade and industry.

The Tragic & Shameful Destruction of Mizdakan and Its Legacy

:

Mizdakan appears to have received its name from Russian archaeologist Aleksandr Yakubovsky who studied the site from 1928 to 1929. He believed the site to be the ancient city of Mizdahkan mentioned in the writings of the medieval writers al-Istakhri and al-Muqaddasi, a native of Jerusalem. Al-Muqaddasi stated that Mizdahkan was surrounded by an expanses of agricultural fields and 12,000 villages. In an attempt to verify this claim, in 1972, archaeologist Vadim Yagodin conducted aerial surveillance photography. He found evidence of 20 to 30 feudal fortresses in the surrounding region, along with remains of surrounding settlements and irrigation canals. Since that time most of these sites have been destroyed up by agricultural development.

Earlier, Mizdakan had been excavated in 1962 and 1964 by No'kis University and the Karakalpak Branch of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences. Regrettably, the practices they employed were extremely poor and considerable damage was done while valuable information about the site was lost because of careless documentation.

The Site, Layout & Location :

Gyaur Kala :

The fortress appears to have been constructed and occupied by the 4th century BCE during the height of the Persian Achaemenian empire. It also appears to have been destroyed by fire towards the end of the 2nd century BCE and then rebuilt and in use from the 1st to the 4th century ACE until it was destroyed yet again.

Necropolis :

The oldest burials sites found are on the north-eastern hill and date back to the 2nd century BCE. These sites show the use of kurgan-like burial practices, a practice prevalent amongst the nomadic people. (Kurgans are mound covered graves that often contained artefacts. memorabilia and items to assist the dead in their afterlife. Usually, the size of the mound indicated the status of the person.) The necropolis was shared by different communities and people of different religious backgrounds.

The eastern hill contains a number of Zoroastrian ossuary burial sites dating from between the 5th to the 8th centuries CE. The highest point of this hill has a nondescript and rather scruff mound known as Djumarat Khassab and named after a revered khassab (meaning butcher) named Djumarat. According to legend, Djumarat came to the mound to hand out meat to the poor and needy in times of bad harvests or famine. Among the many speculative ideas about what the unexcavated mound may conceal, there is some speculation that it might have housed a dakhma (tower of silence) - a highly unlikely proposal as the locale so close to habitation is entirely unsuitable for the purpose.

In the early 7th century the people of Khvarizem began to make ossuaries out of alabaster, many of which were decorated with a scene of mourning that some have interpreted as the legendary death of Siyavush, son of the Kyanian King Kai Kaus - a legend that was later recounted by the poet Ferdowsi in his epic the Shahnameh.

In 651 CE the Arab advance had reached neighbouring Khorasan, overcoming the defenders and capturing the city Merv. It was not long before they would arrive at the outskirts of Mizdakan and in 712 CE, Mizdakan and Khvarizem fell to the Arab onslaught. The Arabs destroyed the Zoroastrian fire temples and according to a report by al-Beruni, killed scores of the Zoroastrian priests. While Zoroastrian burials continued through the 8th and 9th centuries, these would soon cease and the site was used for Muslim burials.

Other Features :

Kyuzeli Gyr :

Of the approximately 400 settlements of the so-called archaic period (7th to 5th centuries BCE) Kyuzeli Gyr is the only fortified settlement indication that it stood at the northeast frontier of Khvarizem and needed to protect its citizens and their livestock from raids.

The 25 hectare site is located on a hill and is surrounded by a three kilometre fortification wall (Tolstov, 1962, pp. 96-104). The lower part of the fortress has open spaces that could have served as a refuge for surrounding inhabitants and their livestock in times of danger and as an enclosure for cattle. Higher up the site, twenty dwellings with courtyards were built beside the fortification wall.

Amongst these uptown dwellings is a palace-like building covering about one hectare that contained a spacious ceremonial hall with six piers and several large fireplaces, had been carefully rebuilt several times. Next to the hall were storage areas with dozens of jars and grain bins. In the southern part of the palace was an open, 800 square metre courtyard, its walls lined with broad benches, amongst which is what appears to be a throne or the place for a throne. These features lead the observe to believe that the courtyard was used for entertainment or parade performances.

Opposite and outside the courtyard, is a four by five metre brick platform which could have been about three metres high. The platform was accessed by a flight of steps at right angles to the platform. Around the base of the platform, excavators found a significant accumulation of cinders and white ash indicating that a fire was maintained on the platform leading some to conclude that the platform was the base for a fire altar.

The site also contains a temple-like building beside which are three tower-like structures with small chambers inside.

Despite reports of kurgan-like burial bounds at the site, no remains of human burials have been found. This lack of human burial remains Kyuzeli Gyr and indeed other sites throughout Khvarizem - at a time where other sites in surrounding lands throughout the steppes contained large numbers of burial kurgans - has led observers to conclude that the residents of Khvarizem were for the main part Zoroastrian.

Gyaur Kala :

Gyaur Kala - Fortress of Infidels Northern wall- the only wall left standing is fast crumbling

Aerial view of the Gyaur Kala site The building to the south of the wall is a modern structure Courtesy: Google Earth

Some 50 kilometres southeast of Mizdakan's Gyaur Kala (see above)

as the crow flies, lies another Gyaur Kala a kilometre and a half

west of an outcrop of hills called the Sultan Uvays mountains (Dag).

While the only walls left standing today are the northern wall and a part of the northwest corner, Gyaur Kala would have been an imposing structure in its prime.

The fortress was built using a unique layout wider at the north end narrowing at the south end. In size, it was approximately 450 metres long and 200 metres wide at the northern end.

The destroyed south-western wall followed the angle of the Amu Darya river bank, which two and a half thousand years ago, would in full flow have run alongside the fortress. The river bank has receded to about 80 metres from the wall.

Soviet archaeologist Sergei Tolstov first excavated the site 1940.

The Tolstov excavation was followed by a more thorough examination by Yuri A. Rapoport and S. A. Trudnovskaya in 1952. Their findings were published in Volume 2 of the Works of the Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition in 1958.

Rapoport and Trudnovskaya found that the massive double mud brick wall walls were built on a plinth (socle) of compacted clay (pakhsa) designed to withstand the force of a battering ram.

Cross section of the Gyaur Kala outer walls and a western side tower. Reconstruction by Yuri A. Rapoport and G. S. Kostina. Image at karakalpak.com Rapoport and Trudnovskaya also found that the outer walls contained two tiers of embrasures. Embrasures are slanted or tapered openings in the wall or parapet of a fortification, tapered so as to be wider on the outside than on the insider so that defenders can fire arrows through it on attackers while limiting exposure to themselves.

The space between the walls was vaulted to support the upper archers' gallery which was roofed with wooden beams, reeds and clay. At the very top of the wall was an open topped gallery, protected by battlements.

The walls were reinforced with towers along each flank and at each corner, the corner towers arranged in an early dove-tail pattern of construction. The towers had three storeys that aligned with the levels within the walls.

The open space within the fortress was divided into two sections by a dividing wall.

The southern section was an open courtyard that could have housed horses or temporary shelters. It could even have been an assembly or training area for troops.

In the northern section's north western corner was a large building which contained a richly decorated hall with wall paintings and clay statues. It's roof was supported by wooden columns that stood on carved stone pedestals. One of the walls contained what the archaeologists feel was a fire altar decorated with a frame designed as a ram's horn.

There is no firm dating on the fortress' construction which appears to have taken place during or before the 4th century BC and remained in use for about seven hundred years during which time the fortress was continually upgraded. The reason for the fortresses decline or disuse are not known.

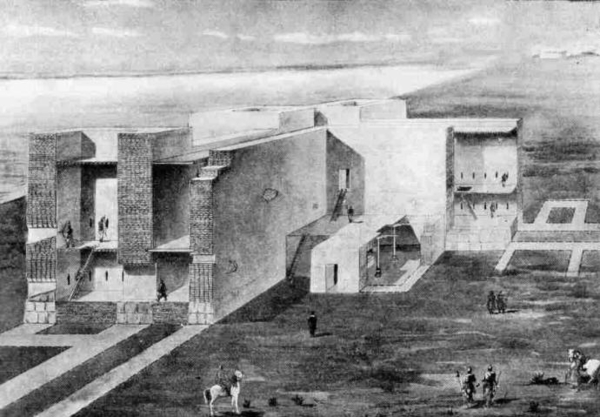

Artist's reconstruction of the great hall Painting by Yuri A. Rapoport and G. S. Kostina. Image at karakalpak.com The fortress was strategically located and would have been in a position to guard water traffic plying the Amu Darya River as well as road traffic in and out of Khvarizem. It was also located and constructed to intercept invasions or hostile incursions along the river and roads leading into the heart of Khvarizem. The fortress' massive size would have been an impressive symbol of Khvarizem military might.

Gyaur Kala is situated 63 kilometres north of Beruni and 81 km south of the provincial capital Nukus (or No'kis). It stands about 14 kilometres from the Badai Tugai forest reserve. The surrounding district of Karakalpakstan is called Qarao'zek tuman.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |