| URVA / KHAIRIZEM - 2 Ayaz Kala :

Aerial view of the Ayaz Kala Complex during winter. With kala 1 (top of the photo), notice the semi-elliptical watch towers all around the outer walls, and the gate-house at the bottom of the kala i.e. beside the outside south wall. The ruins of the palace beside kala 2 can be seen to the left of the kala at the base of the hill. The building within kala 3 can be seen at the top right-hand corner of the kala.

The three kalas stood guard over an oasis and a fertile plain that existed in the first millennium BCE, and provided refuge for the inhabitants when the countryside was under attack by invaders.

While the region around the Ayaz Kala complex is today the semi-arid desert, over two thousand years ago, the Akcha Darya river created a fertile basin and an oasis. The Ayaz Kala lake to the north of the complex was at that time part of the river.

The fortress complex consists of three separate structures :

Ayaz

Kala 1 - The upper level fortress,

Of these, Ayaz Kala 1 is the oldest of the three and dates back to the 4th century BCE.

Ayaz Kala 1 :

Ayaz Kala 1. Photo credit: o spot at Flickr There is no evidence of any permanent buildings having been constructed inside of the fort even though the space within the fortress is quite large. There is, however, evidence of a water storage tank to store collected water.

Arched corridor between Ayaz Kala 1's outside & inside walls Photo credit: SisAnnick at Panoramio For this reason, the fortress is designated as a refugee for local residents rather than one that housed a resident garrison, permanent residents or a palace complex. Presumably, occupants of the fort and those who sought to take refuge within its walls could have used temporary dwellings such as yurts.

The structure is about 180 x 150 metres (600 x 500 feet) in size. The outer ten-meter high walls employed a double wall construction, with the inner and outer walls were separated by a two-meter arched corridor (see left). The roof of the corridor formed a platform on which archers and other defenders could stand. The upper part of the outer wall had slits through which the defenders could fire their arrows.

After its construction, the fortress continued to be strengthened, and by the early third century BCE. Forty five semi-elliptical watch towers that were not part of the original construction were added beside the outer walls the outer walls. There were functional purpose and they also served as reinforcements for the outer walls.

The entrance gateway to the fortress was located at the southern wall. The gateway was a square structure that protruded beyond the outer walls and had an inner and outer gate between which was an inspection chamber. The outer gate was placed at the side of gateway structure and was flanked and supported by two towers. The design required visitors to enter from the side alongside the outer wall. This method of entry allowed the defenders to overlook and observe all who entered, both when the visitors were outside the walls and after they entered the inner inspection chamber. The inspection chamber could have served as a screening and holding room before visitors were cleared to pass through the inner gate. It was overlooked by the ramparts where archers could have positioned themselves to protect against hostile entry.

Ayaz Kala Fortresses 1 (upper level) and 2 (mid-level) as seen from 3 (lower level). Photo credit: lensfodder at Flickr Ayaz Kala 2 :

View of the plains and Ayaz Kala 2 from the upper Ayaz kala 1 Photo credit: zz77 at Flickr Since the site has not be systematically excavated or scientifically dated, it is not known when Ayaz Kala 2 was constructed, though it is thought to be the most modern of the three kalas. Estimates of when different parts of the kala were built range from the 4th to 8th centuries CE. The palace-fort complex could have remained in use until, say, the Mongol invasions of the 13th century CE.

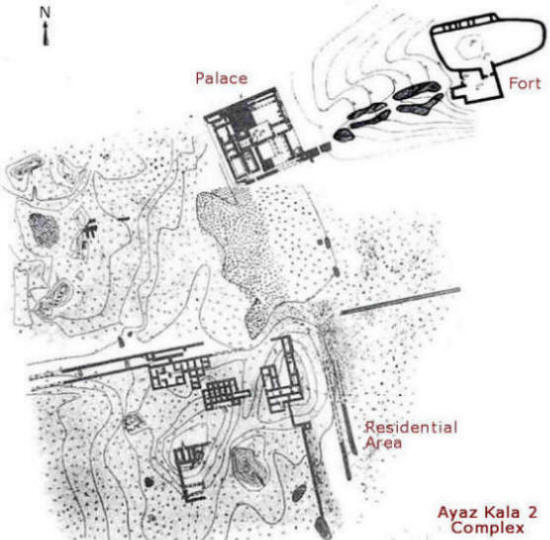

The site is a complex within itself, consisting of a fort, a palace and a residential area. The fort was built atop a conical hillock to the southwest of Kala 1. The picture to the left is a view of the fort from Kala 1 - Kala 1 being located at a higher elevation. The palace was situated below the fort at the base of the hill and was destroyed by two separate fires. To the south of the palace are the ruins of a village-like dwellings that appear to have encircled the base of the hillock.

Ayaz Kala 2 complex Image at History and Culture of Khwarizm History of the Civilizations of Central Asia Volume 3, UNESCO, 1996, by E. E. Nerazik & P. G. Bulgakov Kala 2 is the smallest of the three kalas. The gatehouse to the kala is located at the southern wall at the head of a ramp that leads down to the ruins of a palace complex below.

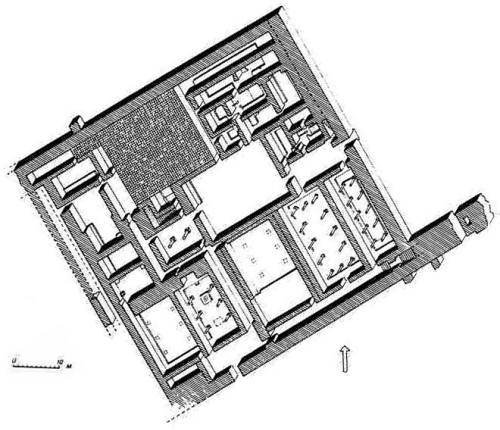

Palace Layout Reconstruction from E. E. Nerazik's In the Lower Reaches of the Oxus and Jaksartes The relatively small size of the kala has led to the theory that rather than being a military fort, the kala was a fortified residence of a feudal landlord. By the 4th to 8th centuries CE a system of feudal landownership had developed similar to the British lords or French nobility. The landowners were called dehqan (the Persian poet Ferdowsi was thought to have been born into a dehqan family), and their agricultural estates were called rustaq. They ruled over a group of serfs (who tilled the lord's land), craftsmen, soldiers and labourers.

Many of the dehqan lived in donjons - relatively small square-shaped fort-like structures that consisted of palatial homes surrounded by a defensive wall. The donjons were usually situated at the head of the canal that watered their agricultural lands.

In the last seventy years, the ruins of most donjons have been destroyed beyond any trace by farmer tilling the land on which the donjons were built. However, one ruin known as Yakke Parsan, has survived 10 kilometres due south of the Ayaz Kala complex.

The walls of Ayaz Kala 2 were built using rectangular mud bricks placed on a foundation of compacted clay known as paksha. The battlements - the upper parts of the outer walls or the parapets appear to have been crenulated, that is, they were given a scalloped or a notched wavy edge. The parapet also had a row of arrow slits running around the entire perimeter.

The almost square entrance gatehouse was on a lower level than the main fort. The fort itself contained a number of rooms, one of which at the north eastern end had a high vaulted ceiling.

Ayaz Kala 3 :

It was constructed in the shape of a parallelogram with square towers at each corner and rectangular towers defending each side. The entrance was in the middle of the western wall and was defended by a strong defensive tower.

As with kala #1, a large part of the interior was an open space. The space could have been used for human and animal refuge during a raid or invasion. A fortified building located in the north east corner contained forty small rooms divided into four groups by two cross-shaped central corridors. Corridors also ran around the sides of three of the outer walls. The fourth wall of the building was joined to the north wall of the fortress.

Two excellent resources are the UNESCO document CentralAsianEarth - Ayaz Kala and David and Sue Richardson's page: Ayaz Qala.

Toprak Kala :

Layout plan of the Toprak Kala site Looking southwest from the heights of Ayaz Kala, a person can see the Elik Kala (fifty fortresses) oasis and in its midst - the fortress of Toprak Kala. Toprak Kala (also spelt Topraq Qala or Turpak Kala), a local name meaning clay fortress, was where the rulers, Shakhs, and nobility of Khvarizem had their residences. It was also an administrative and religious centre, if not the capital of Khvarizem. The rise of Toprak Kala appears to coincide with the decline of Kazakl'i-yatkan, some fourteen kilometres to the southwest.

The

Toprak Kala site contains :

The dating of Toprak Kala is facilitated by the discovered of written records on wood, leather and tablets. The dates that have been determined lead archaeologists to the conclusion that Toprak Kala was built sometime between the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE. Archaeologists tell us that the palace was vacated around in 4th century CE, coinciding with the establishment of the Afrighid dynasty in 305 CE. The rest of the city was in use until the 6th century when it fell into disuse. After that, squatters occupied the premises until the 13th century.

City-Citadel & High Palace Complex :

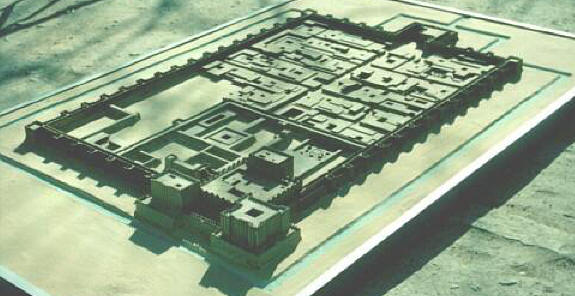

City-Citadel / High Palace Complex reconstruction model Citadel / palace in the foreground Photo credit: Nukus Museum This precisely aligned rectangular site is about 500 by 350 metres in size, with the four corners aligned to the four cardinal points of the compass. The walls were taller than 10 metres in height, reinforced by sixty three rectangular towers and surrounded by a moat. As with Ayaz Kala, the walls and towers had a lower arched passage and an upper archers' gallery.

The site appears to have been fortified residential area or city. It was traversed by a central thoroughfare leading to the north end from the fortified gate. At right angles to this thoroughfare were alleyways that divided the city into ten symmetrical blocks: nine residential-commercial blocks, each with between three and six housing and commercial units, and one block with the main temple. The residential-commercials blocks contained centres that manufactured bronze items, ceramics, textiles and weapons.

At

the end opposite the gate, to the left in the north-western corner,

was an citadel with an elevated palace that is called the high palace.

To the right a large water reservoir.

Citadel / High Palace ruins Photo: Miles Hunter at Flickr The outer walls of the citadel were decorated with niches and projections and were painted with alabaster whitewash, giving the whole structure an appearance similar to that of a Mesopotamian ziggurat.

Windows. Image credit: CyberFair school project The palace had several halls that archaeologists have named based on the artefacts and artwork found in them.

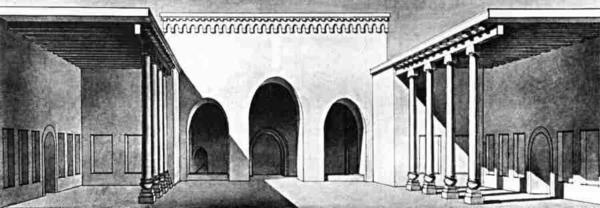

Throne hall (courtyard). Artist's reconstruction by Rapoport and Nerazik. Image at karakalpak.com The Throne Hall. The Throne Hall was located 30 m. from the entrance and was not a hall but a large courtyard covered along the sides. The central covered area had three arches that face the open courtyard and is thought to be the throne room. On either side are two further covered areas called ayvans.

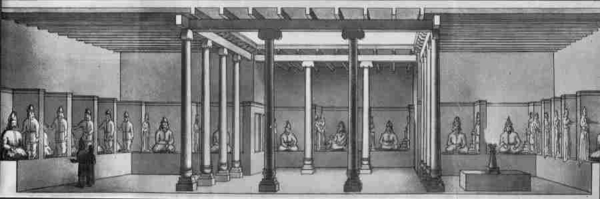

Hall of Kings. Artist's reconstruction by Rapoport and Nerazik. Image at karakalpak.com The Hall of Kings. The Hall of Kings is the largest covered hall, and is so named because the walls of the hall contained 23 or 24 bays or alcoves, each with a clay figure in a seated position, presumed to be that of a previous Khvarizem kings.

Panel of dancing figures - Hall of Dancing Masks Image credit: CyberFair school project There was an fire altar on one side of the hall. The main wall has a centre portion that is recessed and has three alcoves and images. The centre alcove also had what is thought to be the figure of a woman in pink clothing, holding the hand of a child.

The conclusions arrived at by archaeologists and others regarding the identity of other figures are in the usual fashion, unsupported, highly imaginative, speculative, and often absurd.

The Hall of Dancing Masks. The Hall of Dancing Masks was located next to the throne room and had a central podium. In this room, there panels depicting a life size dancing couple, in the centre of each wall, surrounded by niches containing standing figures (see drawing at the right). Fragments uncovered in the ruins of the room suggest that the figures wore masks - hence the somewhat dramatic name.

Four columns that rose from the corners of the podium supported the ceiling.

A decorated wall in the Hall of the Stags. Image: CyberFair school project The Hall of Stags. The walls of the Hall of Stags were decorated sets of five decorative panels. The centre panel had a bas-relief figure of a stag. In a panel above the stag, was a frieze depicting a griffin (see drawing at the left), and in the panels on the sides, were images of trees.

A decorated wall in the Hall of the Warriors Image credit: CyberFair school project The Hall of Warriors. The walls of the Hall of Warriors had life-sized bas-reliefs of dark skinned men framed by stylized rams' horns surrounded by smaller bas-reliefs of men in armour. Rams' horns were a popular method of framing used at several sites. Some have suggested that the images depict military victories.

The Hall of Victories. The walls of the Hall of Victories had repeated bas-reliefs of a king sitting on a throne and flanked by two female figures. The archaeologists who worked on the site speculated that the females figures with deities associated with victory.

Palace-Temple Complex & Attached Enclosure :

A hundred metres north of the High Palace in the City-Citadel complex is the nine hectares site containing the Palace-Temple complex. The Palace-Temple complex consisted of twelve palace-like residences and temple structures built on relatively low platforms.

Two of the temples were connected on their west side by long walls enclosing a processional way to a large, open, 1,250 by 1,000 metre, rectangular walled enclosure. There is no evidence that any structures were built within the compound, nor is there any evidence that any agricultural activity. The walls surrounding the enclosure were, however, massive. Possible uses for a walled open space include a sports field for the entertainment of the residents, and a military training field and parade ground. Today, most of the site has been ploughed under for agricultural use.

Tamga signs :

Tamga signs Image credit: CyberFair school project Tamga

Signs :

Construction Techniques :

The builders used clay with natural stone interspersed for added strength as well as and clay bricks.

Documents :

Toprak Kala's written records Image credit: CyberFair school project In the south-eastern corner of the citadel was an archive where records and other administrative tablets and documents were discovered.

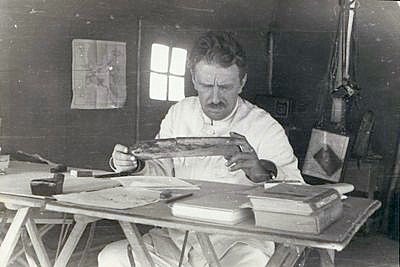

Soviet-era archaeologist Sergey Tolstov examines a 2nd-3rd century CE Khvarizem / Chorasmian wood document Image credit: CyberFair school project and Transoxiana 12 The tablets contained lists of soldiers supplied by the country's nobility or lords (indicated by the Aramaic ideogram BYT'); some names are labelled "present for the first time.". The majority of the soldiers seem to have been slaves rendered by the ideogram ¿BDn. The ratios of slaves to free men in four households were 17:4, 12:3, 15:2, and 3:1 respectively. The owner of each slave was carefully recorded, whether the male head of the house, his wife, or one of the children.

Some documents were written on wood. These documents mainly concerned taxation.

Other palace archive administrative documents include 116 written on leather regarding the delivery and receipt of foodstuffs and other provisions. Some of the documents are dated using Khvarizem's calendar. The days and months are named according to the Zoroastrian calendar. The year of the dates compute to between 188 and 252 CE of the Gregorian calendar.

In two documents the recipient of offerings is designated as ÷LHY÷, meaning king or kings. This has led to speculation that Khvarizem was ruled by two kings simultaneously, each with different functions.

Excavation & Poor Site Management :

Yuriy Aleksandrovich Rapoport and Elena Evdokimovna Nerazik continued working the site and published their findings in the two monographs contained Works of the Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition at Moscow. Volume 12 - Toprak Kala City, was published in 1981 and Volume 14, Toprak Qala, was published in 1984.

Regrettably, as was the case with most Soviet era archaeologists, their interest seemed to be in making discoveries and then abandoning the sites, leaving them unprotected and exposed to the harsh environment and unregulated foot and animal traffic. The methods some used, including bulldozers were boorish. The excavated ruins have become badly eroded over the past thirty years. In would have been better if the ruins had remained uncovered until an excavation incorporating preservation could have been planned. We owe these archaeologists no thanks. We have no idea what priceless treasures and information their recklessness has caused.

If any artwork such as murals had survived on the walls - they have been destroyed by the elements or through human carelessness.

Source :

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/ |